Abstract

Background

Prior research indicates that deficits in emotional abilities are key predictors of the onset and maintenance of eating disorders (ED). As a relatively new emotion-related construct, emotional intelligence (EI) comprises a set of basic emotional abilities. Preliminary research suggests that deficits in EI are linked with disordered eating and other impulsive behaviours. Also, previous research reveals that emotional and socio-cognitive abilities, as well as ED symptomatology, varies across lifespan development. However, while the findings suggest promising results for the development of potential effective treatments for emotional deficits and disordered eating, it is difficult to summarise the relationship between EI and ED due to the diversity of theoretical approaches and variety of EI and ED measures.

Objective

Our study, therefore, aimed to systematically review the current evidence on EI and ED in both the general and clinical populations and across different developmental stages.

Methods

The databases examined were Medline, PsycInfo and Scopus, and 15 eligible articles were identified. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were used.

Results

All the studies reviewed indicated negative associations between EI and the dimensions of ED. Additionally, several mechanisms involved, namely adaptability, stress tolerance and emotional regulation were highlighted.

Conclusion

The systematic review suggests promising but challenging preliminary evidence of the associations between EI and the dimensions of ED across diverse stages of development. In addition, future research, practical implications and limitations are discussed.

Level of evidence I

Systematic review.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The impact of negative emotions on eating behaviours has been examined extensively, although due to its variability, it is difficult to predict how emotion will affect people’s eating habits [1]. Some studies have found that specific emotions, such as anger, fear, sadness and joy, in addition to more lasting and enduring moods, affect food responses during the ingestion process [2, 3]. According to Polivy and Herman, deficits in processing emotions play an important role in the development and maintenance of eating disorders (ED) [4]. As reported by Agras and Telch, difficulties in the regulation of negative affective states might cause an increase in binge-eating behaviour [5]. Theory and empirical research over the last two decades suggest that emotional intelligence (EI), or the ability to process emotional information and regulate emotion adaptively, may be a crucial protective factor in ED, but no systematic review has examined the association between EI and ED and other related behaviours. Synthesising the available evidence on the empirical relationship between ED and EI through a systematic review would allow one to know the state of research in this incipient field of study. Understanding the relationship between EI and ED is critical to guide prevention programmes and treatment approaches for subjects with ED or those at risk of ED. Because of the heterogenous and restricted number of published articles, a systematic review instead of a meta-analysis was conducted.

Emotional intelligence

Two theoretical frameworks are the most commonly accepted in the research literature: mixed models and ability models [6]. The mixed-trait model conceives of EI as a compendium of stable personality traits, socio-emotional competences, motivational aspects and diverse cognitive abilities [7,8,9]. Drawing upon these models, Bar-On [10] defines EI in terms of an array of emotional and social attributes and abilities that influence the overall ability to effectively cope with environmental demands. It is composed of five components: (1) intrapersonal (emotional self-understanding, assertiveness, self-concept, self-realisation, independence); (2) interpersonal (empathy, interpersonal relationships, social responsibility); (3) adaptability (problem-solving, reality testing, flexibility); (4) stress management (stress tolerance, impulse control); and (5) general mood (happiness, optimism). In this mixed EI approach, self-report measures are the measures most typically used.

In Mayer and Salovey’s [11] ability model, EI comprises four interrelated and basic abilities: the ability to perceive, assess and express emotions accurately; the ability to access or generate feelings that facilitate thinking; the ability to understand emotions and emotional knowledge; and the ability to regulate emotions promoting emotional and intellectual growth. This theoretical approach encompasses a set of conceptually related emotional abilities to reason about emotions and to process emotional information to enhance cognitive processes, in which one fundamental and most effective predictor is the emotion regulation ability [12]. Conforming to EI theorists, the EI research tradition is more outcome-oriented in the sense that it seeks to capture the consequences of emotion regulation on health, social and life outcomes and to examine—among other dimensions—individual differences in emotion regulation. In contrast, the emotion regulation research tradition aims to examine issues in a more process-oriented way; that is, it is more focused on the processes by which individuals modify the trajectory of the components of an emotional response. This tradition is more interested in examining the emotion regulation strategies that individuals use to manage their emotions [13, 14]. Regarding age, there are several measures of EI—both the trait and ability approach for the adult population and their respective adaptations for the child and adolescent population. Some authors have reported an increase over time in emotional self-efficacy [15,16,17] and EI ability that become more stable across the age spectrum [18,19,20].

Emotional intelligence and eating disorders

Previous studies have found inverse associations between ED symptoms and various psychological factors that mediate emotional deficit management [21]. For instance, there is evidence that low self-concept and emotion dysregulation are key factors in the appearance and maintenance of ED [22,23,24,25]. Similarly, individuals with high ED scores report low self-esteem and dissatisfaction with body image [26, 27]. Eating disorder symptoms have also been associated with interpersonal problems [28, 29], low levels of assertiveness [29] and more difficulties in recognising facial emotional expression [30]. Furthermore, compared to healthy subjects, ED patients are found to have significantly higher impulsivity scores [31].

On the other hand, in terms of early age, some studies indicate that childhood obesity could predict the risk of ED. In a longitudinal study, it was concluded that 40% of the overweight girls and 20% of the overweight boys—13.4% and 4.7%, respectively—were involved in at least one altered eating behaviour, and they had more than one related behaviour [32]. Other research suggests that a high body mass index (BMI), body comparison, and sociocultural pressure to reduce weight were risk factors for engaging in weight-loss behaviours [33]. In addition, along with their developmental capacities and chronicity, the symptomatic expression of ED varies across infancy and adolescence [34]. Children and adolescents differ from adults both physiologically and emotionally as they make the transition from child to adult and, thus, with significant advances in the development of emotional self-control. Literature in developmental psychology reveals that emotional abilities constitute an important, continuing topic throughout childhood, adolescence, and adulthood and that each developmental transition is associated with change in one’s affective skills. These processes are present in infancy but continue improving throughout adolescence into adulthood and may underlie the emergence and prevalence of ED in different stages. In short, compared to adults, children and adolescents report more limited verbal skills, lower abstracting problem-solving abilities, less awareness of emotions, and reduced cognitive control of impulsive behaviour [34]. These developmental differences highlight the difficulties in diagnosing ED and its correlates and symptoms in children and adolescents. Likewise, a recent study carried out with 30,000 individuals with ED across five different developmental stages (early adolescence, late adolescence, young adulthood, early-middle adulthood, and middle–late adulthood) [35] revealed that, beyond similarities in central symptoms, the network structure or interconnectivity of ED symptoms vary significantly from adolescence to adulthood. Moreover, the potential deficits in emotional skills might interfere with these necessary developmental transitions in a manner that might increase the risk of appearance of ED, accounting for differences in prevalence and intensity across different developmental stages.

Using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [36], the present work aims to systematically review the studies on EI and ED to obtain a broader understanding of the empirical link between ED and EI through different theoretical conceptualisations of EI, different stages of lifespan development (childhood, adolescence, youth and adulthood) and several types of population (general and clinical). Reviewing and summarising this corpus of knowledge could allow the development of a clear image of the current state of research and propose future lines of research to complement the existing gaps in the field.

Methods

Exhaustive searches were conducted in the PsycINFO, Medline and Scopus databases between 6–13 November 2019. We handled a computerised literature search, locating articles published in English or Spanish without any limitation of time or age. The term ‘emotional intelligence’ was used as a keyword or term in the title or summary, along with the following expressions: ‘eating disorders’, ‘binge eating’, ‘bulimia’, ‘anorexia’ and ‘body mass index’. We also performed manual searches of reference lists that allowed us to complement our study’s database.

The articles that met the following criteria were included in our review. The first criterion was that the studies had to be based on empirical research; so, theoretical studies and reviews were excluded. The second criterion was that the articles had to examine the association between EI and ED or symptoms of ED as related variables. The third criterion was that the EI evaluation tools had to be based on a theoretical EI model, and that they must assess at least one dimension of EI. Studies based on other theoretical perspectives (e.g., dysregulation of emotion or emotional functioning) were, therefore, excluded.

We identified 84 potentially eligible studies in the initial searches: 22 in PsycINFO, 16 in Medline and 46 in Scopus. Forty-nine relevant studies remained after eliminating the 35 duplicates. In this phase, two independent researchers examined the titles and abstracts against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and a third researcher was consulted in cases of disagreement. At this stage, our review led to the exclusion of studies, because: (1) they did not study EI and ED as the main variables; (2) they were not based on an EI framework, or (3) they were not empirical studies. At the end of this selection process, 38 studies were excluded, resulting in 11 articles that fulfilled all the inclusion criteria. We also included four articles found through manual searches that met all the criteria. These 15 documents were examined in their entirety and formed our final set of studies that actually investigated EI and ED as the main variables. There was only one study with children that examined the link between EI and emotional eating behaviour (Fig. 1).

Instruments

The instruments used to measure ED in the studies were as follows:

-

Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26) [37] is the most frequently used test in the included studies [6 of 15]. It is a 26-item questionnaire that comprises three subscales: dieting, bulimia and food preoccupation, and oral control. Acceptable internal consistency reliability estimates for the subscales are as follows: dieting—0.92, bulimia/food preoccupation—0.86, and: oral control—0.71 [38].

-

Bulimia Test Revised (BULIT-R) [39] is a 36-item self-report that measures the degree of bulimic attitudes and behaviours, with excellent internal consistency: 0.98 [40].

-

Praeger Questionnaire Emotional Eating (PQEE) [41] evaluates emotional feeding through 16 items of food consumption, with adequate internal reliability ranging from 0.72 to 0.85 in previous studies [41].

-

Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) [42] is a 36-item self-report measure of ED symptomatology and behaviours across four subscales: dietary restraint, weight concern, shape concern and eating concern. Test–retest correlations ranged from 0.66 to 0.94 for scores on the four subscales [43].

-

Eating Disorders Diagnostic Scale (EDDS) [44] is a 9-item self-report scale for diagnosing anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN) and binge-eating disorder. Average internal consistency is 0.89 [44].

-

Eating Disorder Inventory II (EDI-II) [45] is a 9-item self-report that assesses the behavioural and cognitive patterns associated with ED. Cronbach’s alpha for anorexia scale is 0.90 and for bulimia, it is 0.83 [45].

-

Food Preoccupation Questionnaire (FPQ) [46] is a 28-item self-report that evaluates rigidity, excess participation and concern for food, and food consumption. The questionnaire demonstrated good reliability and construct validity [46].

-

Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory-ED Scale (MACI) [47] evaluates a clear tendency to AN or BN and image perception, conditioned by fear of obesity. The reliability of the scales has been proven internationally on repeated occasions [48].

-

Eating Disorder Inventory 3 (EDI-3) [49] contains 12 main scales: three specific ED—obsession with thinness, bulimia and body dissatisfaction—and nine psychological/general ones. It has shown good internal consistency (0.91 for girls and 0.84 for boys) [49].

-

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview Eating Disorder (module of the DSM-IV; M.I.N.I. Kids 6.0) [50] is a diagnostic interview based on DSM-IV criteria. For any eating disorder, the area under curve (AUC) ranges between 0.81 and 0.96, and the Kappa coefficient ranges between 0.56 and 0.87 [50].

-

Child Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (CEBQ) [51] is a multidimensional, parent-report questionnaire measuring children’s eating behaviour and is designed to assess eating styles related to obesity risk. The instrument is composed of 35 items and eight scales (responsiveness to food, enjoyment of food, satiety responsiveness, slowness in eating, fussiness, emotional overeating, emotional undereating and desire for drinks). The scale’s internal consistency was acceptably high (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.83) [51].

To measure IE, the following instruments were used:

-

Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory (original version) (EQ-i) [52] is a self-report measure with 133 items and includes five factors: intrapersonal, interpersonal, adaptability, stress management and general mood. EQ-i’s global internal consistency coefficient is 0.97 [52].

-

Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory (short version) (EQ-i:S) [53] is a self-report measure with 51 items and includes the five factors of its original version [52]. Studies of reliability have yielded a Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.76 to 0.93 [53].

-

Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory (youth version) (EQ-i: YV) [54] is a self-report measure with 60 items and also includes the five factors of its original version [52]. Estimates of internal consistency ranged from 0.65 to 0.90 [54].

-

Trait Meta Mood Scale (TMMS-30) [55] is a self-report questionnaire that measures trait EI and consists of 30 items with three intrapersonal dimensions: attention, clarity and emotional repair. Acceptable values for Cronbach’s alpha in attention: 0.86, clarity: 0.88 and repair: 0.82 were reported [55].

-

Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS) [56] is a self-report questionnaire that measures trait EI and contains 20 items comprising four subscales: evaluation of emotion in oneself, evaluation of emotion in others, use of emotion and regulation of emotion. The WLEIS was used in its Hebrew version [55] which showed adequate Cronbach’s alpha internal reliability ranging from 0.72 to 0.85 in previous studies [56] and also in its Chinese version [57], whose Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency was 0.89 [56].

-

Schutte Emotional Intelligence Scale (SEIS) [58] is a self-report test of 33 items composed of four subscales: evaluation, expression, regulation and use of emotion, with an adequate internal consistency of 0.90 [58].

-

Audio–Visual Test of Emotional Intelligence (AVEI) [59] consists of a 27-item skills test, based on the recognition and analysis of emotions through images and short videos, which are framed in two of the four branches defined by Mayer et al. [6] It has good reliability and predictive validity [59].

-

Multidimensional Emotional Intelligence Evaluation Scale (MEIA) [60] evaluates self-perceived personality traits in emotional functioning. It is composed of 116 items based on Salovey and Mayer’s original model [61]. The overall Cronbach’s alpha of the factor-based scale representing the entire test was 0.96 [62].

-

Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test Version 2.0 (MSCEIT) [63] includes 141 items and is framed within the EI ability model. It includes the four areas proposed in the Mayer and Salovey model: perception, facilitation, understanding and emotional management. The overall EI test score reliability was r = 0.93 for consensus and 0.91 for expert scoring [64].

-

Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire—Adolescent Short Form (TEIQue-ASF) [65] (Spanish version) is a 30-item self-report instrument that measures the global trait EI. The test has exhibited an internal consistency of 0.82 [65].

-

Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces (KDEF) [66] is based on the ability model of Mayer et al. [6]. This task involves recognising facial emotions with 20 standardised colour photographs of the faces of young European adults showing four types of facial expressions: happy, angry, sad and neutral. The average success rate skewed was 72% [67].

Results

Fifteen articles were included in our review and were classified into five developmental stages of subjects included in the studies: (1) adults and young adults; (2) young adults and adolescents; (3) adolescents; (4) adolescents and children, and (5) children. Some of these categories overlapped due to the sample ages of included studies. Of the 15 studies, 14 were performed in general population samples and one was performed in a clinical sample.

Seven studies were identified as examining EI and ED in an overlapping adult population with a young adult population, all of them using cross-sectional designs.

Three used EI self-report measurements, three combined EI self-report measures with performance-based instruments, and only one used performance-based EI measures exclusively. The description of the 7 studies, the EI assessment tools and the main findings are presented in Table 1.

Findings in adults and young adults using self-report EI measures

Costarelli, Demerzi and Stamou [68] used the EQ-i [52]. Their results showed that women who reported ED attitudes demonstrated lower levels of EI compared to counterparts who did not have ED attitudes. In addition, they found significant positive associations between anxiety levels and EI.

Zysberg and Rubanov [69] used the Hebrew version of the WLEIS [56]. The results indicated a strong association between EI and emotional eating, in such a way that the highest EI scores are associated with a lower tendency to eat emotionally and vice versa. When using a hierarchical regression model, it was observed that age and sex had no significant effect on emotional eating, and education had a moderate effect.

Foye, Hazlett and Irving [70] used the SEIS [58] to measure EI. They used additional subscales conforming to the analysis of Lane et al. [71] to provide a six-faceted EI score (appraisal of others’ emotions, appraisal of own emotions, emotional regulation, social skills, emotional utilisation and optimism). The findings indicated negative associations between overall EI and EAT-26 [37] total scores. These associations stayed significant for only four features of the EI construct: appraisal of own emotions, emotional regulation, emotional utilisation and optimism. For those reporting a history of ED, these associations remained significant, whereas for those with no background of ED, correlations between EAT-26 and emotional regulation and emotional utilisation were not significant.

Findings in adults and young adults using self-report and ability EI measures

Zysberg and Tell [72] used the SEIS [58] to test for EI and the AVEI to measure EI ability [59]. Based on the preliminary evidence indicating an association between EI and ED, they examined the mediation role of perceived control in the EI-ED link. In general, the results indicated that perceived control mediated the association between the EI and risk of ED scores for both AN and BN.

Zysberg [73] also used the SEIS and the AVEI. The author reported a correlation between the SEIS and two of the three indexes of ED; after controlling statistically for the potential shared variance, results showed a non-significant association between SEIS and body dissatisfaction. No association was found with any of the variables, except for a moderate association with body image. Although considerable adjustment was made for potential confounding variables, the AVEI showed a statistically moderate association with disordered eating patterns.

Gardner, Quinton and Qualter [74] evaluated EI constructs with two different measures: a trait EI measure, namely the MEIA [60] and a skill EI measure, the MSCEIT Version 2.0 [63]. For both instruments, they used the total score to measure the upper level, the factors to measure the average level and the concrete facets to measure the lowest level of EI. Their findings revealed a negative correlation between the global trait EI and global bulimic symptoms, and binge eating at the upper level of EI; however, they found no correlation between bulimic symptoms and the highest level of EI skill. At the intermediate and lower levels of EI (factors and facets), they found negative correlations with bulimic symptoms for both trait EI and EI skill.

Findings in adults and young adults using ability EI measures

Hambrook, Brown and Tchanturia [75] used the MSCEIT Version 2.0 [63], in a clinical trial with control group. The main finding was that the AN group had a significantly lower performance than the control group in terms of their overall EI. The AN group also demonstrated a significantly poorer EI in the MSCEIT change task, which measures the understanding of how specific emotions can result from the intensification of another feeling.

In agreement with Cohen’s [76] standard, the correlation coefficients represent effect sizes from small (r = − .477; p < .001) between emotional regulation and ED [70] to large (r = .72; p < .001) between EI and emotional eating [69].

Findings in the young adults and adolescent population

Our search identified four articles that analysed the relationship between EI and ED in the young adults and adolescent population following cross-sectional designs. All used self-reported measures of EI traits. The description of the four studies, the EI assessment tools and the main findings are presented in Table 2.

Findings in young adults and adolescents using self-report EI measures

Markey and Vander Wal [77] used the EQ-i: S [53]. The results showed that a lower EI predicted significantly greater bulimic symptomatology.

Filiare, Laure and Rouveix [78] also used the EQ-i [52]. They found that men with ED attitudes (athletes and control) had lower levels of EI compared to groups without ED, in the following factors: intrapersonal, adaptability, tolerance to stress and general mood. They also found that athletes had higher levels of EI subscale scores compared to the control group (interpersonal and impulse control) and that athletes with ED had significantly lower scores on the subscales of happiness, flexibility, empathy and emotional self-awareness in comparison with athletes without ED. In the group of ED attitudes (athletes and control), the EAT-26 [37] was negatively correlated with tolerance to stress, emotional self-awareness and general mood, and positively with body dissatisfaction.

Pettit, Jacobs, Page and Porras [79] evaluated EI with the reduced version of the TMMS-30 [55]. Their findings revealed an inverse relationship between EI factors (clarity and repair) and food concern/bulimia. Perception of EI factors combined with gender was also significantly related to diet, food concern/bulimia and general eating attitudes.

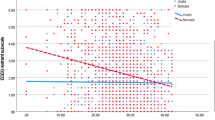

Li [80] used the WLEIS [56] in a version adapted to the Chinese population [57]. The results showed a negative correlation of moderate magnitude between EI and ED risk as measured by the subscales of EAT-26 [37]. As main effects, the results found that the girls and the obese group had a significantly higher risk of ED than the boys and the underweight, normal and overweight groups. After controlling for gender and body size as potential confounding variables, EI predicted the risk of ED negatively; that is, subjects who showed higher scores in EI scored lower in ED on the EAT-26 questionnaire.

According to Cohen’s [76] standard, the correlation coefficients represent small effect sizes (r = − .177; p < .01) between clarity and bulimia/food concern [79] and large ones (r = − .41; p < .001) between EI and ED risk [80].

Findings in the adolescent population

Our search identified two articles that analysed the relationship between EI and ED in the adolescent population, following cross-sectional designs. Both studies used self-reported measures of EI traits. The description of the two studies, the EI assessment tools and the main findings are presented in Table 3.

Findings in the adolescent population using self-report EI measures

Zavala and López [81] used the EQ-I: YV to assess perceived EI [54]. Their results showed significant negative correlations between the total EI score and disposition to ED, specifically in three of the four scales: intrapersonal, stress management and adaptability. Findings also showed significant differences between the sexes, with the disposition to ED being higher in women.

Peres, Corcos, Robin and Pham-Scottez [82] used the EQ-I: YV [54] to analyse EI differences between a group of girls diagnosed with AN, using interviews based on the DSM-IV criteria and a control group. They found significant differences between both groups on the scales for intrapersonal EI and general mood.

Findings in the adolescent and child population

We only found a single article that examined the relationship between EI and ED in a sample of children and adolescents between 10 and 17 years of age. Cuesta, González and García [83] used the Spanish version of the TEIQue-ASF [65], via a cross-sectional design. They used self-reported measures of EI traits.

Their findings indicated that the EI trait was significantly and negatively correlated with the total scores of ED symptoms and with all the subscales of the EDI-3 [49] in preadolescent boys, preadolescent girls and adolescents. After controlling for the effect of BMI as a potential confounding variable, the EI trait was a significant and predictive variable of ED symptoms in all groups: preadolescent girls (22%), adolescent girls (23%), preadolescent children (17%) and adolescents (13%) (see Table 3).

Findings in the child population

We only found one article that, although it did not specifically analyse the relationship between EI and EDs, compared emotional eating behaviour (an eating practice associated with obesity risk) with EI and identification of facial emotions in a sample of children between 6 and 10 years of age. Koch and Pollatos [84] evaluated the relationship between EI and food imbalances in a sample of children using two of the five scales (intrapersonal and interpersonal) of the EQ-i: YV [54] via a cross-sectional design. They also used the task from the KDEF [66]. To measure emotional eating, they used the CEBQ [51]. It is a parent-report measure. Their findings indicated that EI did not differ significantly between the groups of overweight/obese and normal weight children; however, the group of overweight/obese children scored significantly higher on the CEBQ (i.e., they reported a high degree of emotional eating behaviour) than the group of normal weight children. They also found significant negative correlations between intrapersonal and interpersonal EI and reaction time in the recognition of facial emotions. Similarly, excessive emotional eating and the success rate in recognising sad faces in the KDEF task were negatively correlated (see Table 3).

Discussion

In recent decades, a series of studies have examined the impact of personality factors on the development and maintenance of ED [85]; more recently, the potential role of emotions and emotional abilities in ED has attracted the attention of many researchers. The present review systematically analysed fifteen articles published between 2007 and 2019 and examined the association between EI and ED in both general and clinical populations. A negative relationship between total EI dimensions and different ED symptoms was reported; that is, individuals with high levels of EI reported fewer eating behaviours and concerns than those with low EI. As far as we know, this is the first study that summarises the literature on associations between EI and ED. Reviewed studies indicate a negative relationship between EI and ED across different developmental stages, independently of whether EI was measured by skill and self-report tests.

Mechanisms involved in the relationship between EI and ED

Our findings highlight some mechanisms involved in the association of EI with ED. For example, Li [80] provided results indicating that social anxiety partially mediates the relationship between EI and the risk of ED. By adding social anxiety to the model, the direct effect of EI on the risk of ED decreased substantially, although it remained significant. Emotionally intelligent individuals may be less afraid of being evaluated negatively, thus decreasing the risk of ED. Previous studies have indicated a close relationship between social anxiety and ED [86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93].

Two studies in our review considered additional approaches along with examining the association between EI and ED. Both involved data supporting the mediation of anxiety in the relationship between EI and ED. Hambrook et al. [75] found that the performance of EI was closely related to the level of self-reported anxiety. Their data suggested that anxiety mediated the observed relationship between the diagnosis of AN and EI. Similarly, prior studies found that differences in alexithymia between AN and control groups disappear after statistically controlling for anxiety [94, 95]. Deficits in identifying and communicating emotions in individuals with AN might, therefore, be secondary to personal distress, rather than being attributed to the presence of AN. Lower EI in people with AN might be attributed to higher experienced anxiety, which would interfere with the ability to reason accurately about emotions and use emotional information to make adaptive decisions in a social context. Peres et al. [82], reported difficulties in emotional processing in the AN group compared to the healthy control group, finding that some of the differences at the Intrapersonal, stress management, and the total score of EI, might be explained by anxiety or depression.

The findings of Markey and Vander Wal [77] suggest that there is a significant association between negative affect and bulimic symptomatology, independent of EI association and bulimic symptomatology. They did not find any significant effect according to the level of EI between the association of negative affect and ED. Previous research has identified negative affect as a predictor of binge eating [5] and coping as a moderator in the relationship between negative affect and binge eating [96]. Consequently, people with greater positive affect could face emotional situations in a more adaptive way as a potential protective factor against developing ED.

Beyond examining the association between EI and ED, Zysberg and Tell [72] considered an additional approach. They argued that EI could affect perceived control and that this would be positively associated with AN and negatively associated with bulimic symptoms. Their findings partially supported the mediating model. Perceived control mediated associations between the EI and ED scores for AN and BN. Perceived control is positively associated with EI and is a concept that revolves around the effective management and regulation of emotional reactions [97, 98]. Therefore, perceived control might be a factor to take into consideration in further research. Individuals who perceive greater self-control may be more effective at emotional self-regulation, thus emphasising its potential role as a protective factor against the development of some dysfunctional eating behaviours such as BN and binge eating, while other people who perceive high self-control may be at higher risk of AN.

Limitations of included studies

We found several limitations when analysing the literature in this field. First, there were limitations involving the heterogeneity of the EI instruments used. Nine different questionnaires were used to evaluate EI—six for trait EI, and three for ability. Trait EI measures were used in nine studies; only one study used ability EI measures, and four studies used trait and ability measures jointly. Second, most of the studies have not used diagnostic instruments to assess specific types of ED, but they have used a wide range of different and heterogeneous questionnaires to detect the risk of ED (i.e., eating attitudes or behaviours). In general, 11 different measures were used to evaluate these eating behaviours. Therefore, it was not possible to provide empirical associations between specific types of ED and EI abilities. In addition, due to the heterogeneity of the instruments used for measuring EI and ED/ED risk, the variety of samples used at different stages of life and the multiple theoretical EI approaches employed, it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis study. The instruments used to measure ED/ED risk do not consider the changes included in the DSM-5. Third, all studies used a cross-sectional design. The lack of prospective research in this field thus limits interpretations of the relationship between variables, hampering any casual inference. Fourth, the age ranges of the samples of some of the selected studies were not well adjusted to a developmental age category, causing overlapping with other age categories and thus not allowing for an exhaustive and homogeneous classification of studies according to age group samples. Therefore, future studies should include samples in consonance with the context of the characteristics of normal development, especially in early and late adolescence. Finally, no study was found on the specific association of EI and ED in children. Only one study to date has examined the association of EI with emotional eating behaviour as an eating style associated with the risk of obesity in children.

Future research and practical directions

Our review proposes a series of methodological gaps that should be considered in future research to deepen the current understanding of EI and ED. Zysberg and Tell [72] suggest that there may be essential differences in the dynamics of personal factors associated with ED behaviour in clinical and non-clinical samples. Future studies should, therefore, compare both samples. Similarly, while there is a body of research examining the role of eating behaviours in non-clinical samples, more research is needed to analyse the role of EI in clinical samples [77]. There are potential gender and age differences in EI, so future studies should examine in depth how EI is differently associated with ED in women and men, and in different developmental groups [83]. As EI involves different EI abilities, further research might examine which EI subdimensions are most strongly associated with ED symptoms [68]. In the same sense, Gardner et al. [74] question the usefulness of prolonged evaluations of EI. The inclusion of diagnostic instruments and DSM-5 criteria when evaluating ED could provide more homogeneous data adapted to the current situation.

These findings can help to boost further research in the field of the conceptual validation of EI and in the study of ED risk factors and symptoms. Certainly, more consistent findings are necessary in both clinical and non-clinical samples. Identifying potential risk factors could contribute to the development of simpler and more effective measurement instruments that could help to better understand psychotherapeutic interventions. This would provide clinicians with a potential intervention guide for individuals suffering from ED, assisting them in their early identification and in a promising intervention. Our systematic review thus provides some insightful information for the development of preventive programmes based on EI to minimise the risk of ED in populations potentially at risk, such as children and adolescents.

Conclusion

The present systematic review suggests promising but challenging preliminary evidence of the associations between EI and ED/ED risk across different stages of development. Future longitudinal cohort investigations might be useful for a theoretical understanding of the nature of EI and its associations with various eating-related behaviours. If the proposed model is supported, it could potentially be used to guide prevention programmes for individuals at risk of ED and more precise interventions than those currently available for individuals who suffer from ED.

What is already known on this subject?

Individuals with ED and at risk of ED usually report difficulties managing their own emotions. These emotional deficits lead to the maintenance and development of ED symptomatology. However, no previous systematic review has synthesised the available evidence on the empirical link between ED and EI.

What does this study add?

A summary view of the existing research on the relationship between EI and ED/ED risk across developmental stages. A negative relationship between EI dimensions and different ED symptoms and attitudes was found across the included studies. These results underline the need for including emotional abilities in the development of prevention programmes and therapeutic interventions for individuals with ED or in at-risk situations that complement the existing cognitive–behavioural approach.

References

Macht M (2008) How emotions affect eating: a five-way model. Appetite 50(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2007.07.002

Ekman P (1992) An argument for basic emotions. Cogn Emot 6:169–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699939208411068

Frijda N (1993) Moos, emotion episodes, and emotions. Handbook of emotions. Guilford Press, London, pp 381–403

Polivy J, Herman CP (1993) Etiology of binge eating: psychological mechanisms. Guilford Press, London

Agras W, Telch C (1998) The effects of caloric deprivation and negative affect on binge eating in obese binge-eating disordered women. Behav Ther 29:491–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7894(98)80045-2

Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso D (2000) Models of emotional intelligence. In: Sternberg RJ (ed) Handbook of Intelligence. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 396–420. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511807947.019

Bar-On R (2000) Emotional and social intelligence: Insights from the emotional quotient inventory. In: Bar-On R, Parker JDA (eds) Handbook of Emotional Intelligence. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, pp 363–388

Boyatzis R, Goleman D, Rhee K (2000) Clustering competence in emotional intelligence: Insights from the emotional competence inventory (ECI). In: Bar-On R, Parker JDA (eds) Handbook of Emotional Intelligence. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, pp 343–362

Goleman D (1995) Inteligencia emocional. Kairós, Barcelona

Bar-On R (1997) The emotional quotient inventory (EQ-I): technical manual. Multi-Health Systems, Toronto

Mayer JD, Salovey P (1997) What is emotional intelligence? In: Salovey P, Sluyter D (eds) Emotional development and emotional intelligence: implications for educators. Basic Books, New York, pp 3–31

Salovey P (2007) Prologo. In: Mestre y JM, Fernández-Berrocal P (eds) Manual de Inteligencia Emocional. Pirámide, Madrid, pp 17–19

Peña-Sarrionandia A, Mikolajczak M, Gross JJ (2015) Integrating emotion regulation and emotional intelligence traditions: a meta-analysis. Front. Psychol 6:160. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00160

McRae K, Gross JJ (2020) Emotion regulation. Emotion 20(1):1

Bar-On, R (2006) The Bar-On model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI). Psicothema, 18, supl., 13-25

Cabello R, Sorrel MA, Fernández-Pinto I, Extremera N, Fernández-Berrocal P (2016) Age and gender differences in ability emotional intelligence in adults: a cross-sectional study. Dev Psychol 52(9):1486

Keefer KV, Holden RR, Parker JDA (2013) Longitudinal assessment of trait emotional intelligence: measurement invariance and construct continuity from late childhood to adolescence. Psychol Assess 25(4):1255–1272. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033903

Pons F, Harris P, de Rosnay M (2004) Emotion comprehension between 3 and 11 years: developmental periods and hierarchical organization. Eur J Develp Phychol 1:127–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405620344000022

Denham SA (2007) Dealing with feelings: how children negotiate the worlds of emotions and social relationships. Cognit Brain Behav 11(1):1–48

Saeki E, Watanabe Y, Kido M (2015) Developmental and gender trends in emotional literacy and interpersonal competence among Japanese children. Int J Emot Educ 7:15–35

Waxman SE (2009) A systematic review of impulsivity in eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev 17:408–425. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.952

Hartmann A, Zeeck A, Barrett MS (2010) Interpersonal problems in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 43:619–627. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20747

Hsu L (1990) Experiential aspects of bulimia nervosa—implications for cognitive behavioral-therapy. Behav Modificat 14(1):50–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/01454455900141004

Perry JA, Silvera DH, Neilands TB, Rosenvinge JH, Hanssen T (2008) A study of the relationship between parental bonding, self-concept and eating disturbances in Norwegian and American college populations. Eat Behav 9(1):13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.01.007

Ridout N, Wallis DJ, Autwal Y, Sellis J (2012) The influence of emotional intensity on facial emotion recognition in disordered eating. Appetite 59(1):181–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.04.013

Stein KF, Corte C (2007) Identity impairment and the eating disorders: content and organization of the self-concept in women with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev 15(1):58–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.726

Connors M, Johnson C (1987) Epidemiology of bulimia and bulimic behaviors. Addict Behav 12(2):165–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(87)90023-2

Fox JR, Powe MJ (2009) Eating disorders and multi-level models of emotion: an integrated model. Clin Psychol Psychother 16:240–267. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.626

Goldner E, Srikameswaran S, Schroede M, Livesley W, Birmingham C (1999) Dimensional assessment of personality pathology in patients with eating disorders. Psychiatry Res 85(2):151–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1781(98)00145-0

Stice E, Shaw H (2004) Eating disorder prevention programs: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 130:206–227. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.206

Ross M, Wade T (2004) Shape and weight concern and self-esteem as mediators of externalized self-perception, dietary restraint and uncontrolled eating. Eur Eat Disord Rev 12(2):129–136. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.531

Neumark-Sztainer DR, Wall MM, Haines JI, Story MT, Sherwood NE, Van den Berg PA (2007) Shared risk and protective factors for overweight and disordered eating in adolescents. Am J Prev Med 33(5):359–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.031

Muris P, Meesters C, Blom W, Mayer B (2005) Biological, psychological, and sociocultural correlates of body change strategies and eating problems in adolescent boys and girls. Eat Behav 6(1):11–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.03.002

Bravender T, Bryant-Waugh R, Herzog D, Katzman D, Kreipe RD, Lask B et al (2007) Classification of child and adolescent eating disturbances. Workgroup for Classification of Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents (WCEDCA). Int J Eat Disord 40:117–122. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20458

Christian C, Perko VL, Vanzhula IA, Tregarthen JP, Forbush KT, Levinson CA (2020) Eating disorder core symptoms and symptom pathways across developmental stages: a network analysis. J Abnorm Psychol 129(2):177–190. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000477

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009(339):b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

Garner DM, Garfinkel PE (1979) The eating attitudes test: an index of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med 9(2):273–279. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291700030762

Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE (1982) The Eating Attitudes Test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med 12:871–878. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291700049163

Thelen MH, Farmer J, Wonderlic S, Smith M (1991) A revision of the bulimia test: the BULIT-R. Psychol Assess 3(1):119–124. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.3.1.119

Thelen MH, Mintz LB, Vander Wal JS (1996) The bulimia test-revised: validation with DSM-IV criteria for bulimia nervosa. Psychol Assess 8:219–221. https://doi.org/10.1037//1040-3590.3.1.119

Praeger S (2005) Emotional eating, Part I [Hebrew] Tel Aviv. United Books, Israel

Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ (1994) Assessment of eating disorder psychopathology: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eating Disord 16(4):363–370

Berg KC, Peterson CB, Frazier P, Crow SJ (2012) Psychometric evaluation of the eating disorder examination and eating disorder examination-questionnaire: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord 45(3):428–438. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20931

Stice E, Telch CF, Rizvi SL (2000) Development and validation of the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale: a brief self-report measure of anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder. Psychol Assess 12(2):123–131. https://doi.org/10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.123

Garner DM (1991) Eating disorder inventory-2 manual. Psychological Assessment Recourses Inc, Odessa

Tapper K, Pothos EM (2010) Development and validation of a Food Preoccupation Questionnaire. Eat Behav 11(1):45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.09.003

Millon T (2004) MACI. Inventario Clínico para Adolescentes de Millon. Manual. TEA, Madrid

Millon T (1993) Manual of millon adolescent clinical inventory. NCS, Minneapolis

Garner DM (2004) Eating disorder inventory 3 (EDI-3). Professional manual. Odessa. Psychological Assessment Resources, Fl

Sheehan DV, Sheehan KH, Shytle RD, Janavs J, Bannon Y, Rogers JE et al (2010) Reliability and validity of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview for children and adolescents (MINI-KID). J Clin Psychiatry 71(3):313–326. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.09m05305whi

Wardle J, Guthrie CA, Sanderson S, Rapoport L (2001) Development of the children’s eating behaviour questionnaire. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 42(7):963–970. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00792

Bar-on R (1997) The emotional quotient inventory (EQ-i): a test of emotional intelligence. Multi-Health Systems, Toronto

Bar-on R (2002) Bar-on EQ-i: S technical manual. Multi-Health Systems, Toronto

Bar-on R, Parker JDA (2000) Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory (youth version): technical manual. Multi-Health Systems, Toronto

Salovey P, Mayer JD, Goldman SL, Turvey C, Palfai TP (1995) Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In: Pennebaker JW (ed) Emotion. Disclosure and health. American Psychological Association, Washington, pp 125–151

Wong CS, Law KS (2002) The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitudes. Leadersh Q 13(3):243–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00099-1

Li T, Saklofske DH, Bowden SC, Yan G, Fung TS (2012) The measurement invariance of the wong and law emotional intelligence scale (WLEIS) across three Chinese university student groups from Canada and China. J Psychoeduc Assess 30(4):439–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282912449449

Schutte NS, Malouff JM, Hal LE, Haggerty DJ, Cooper JT, Golden CJ et al (1998) Development and validation of a measure of emotional intelligence. Pers Individ Differ 25(2):167–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00001-4

Zysberg L, Levy A, Zisberg A (2011) Emotional intelligence in applicant selection for care-related academic programs. J Psychoeduc Assess 29(1):27–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282910365059

Tett RP, Fox KE, Wang A (2005) Development and validation of a self-report measure of emotional intelligence as a multidimensional trait domain. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 31(7):859–888. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204272860

Salovey P, Mayer J (1990) Emotional intelligence. Imagin Cogn Pers 9(3):185–211. https://doi.org/10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

Mayer JD, Caruso DR, Salovey P (1999) Emotional intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence 27:267–298

Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR (2002) Mayer-salovey-caruso emotional intelligence Test (MSCEIT): user’s manual. Multi-Health Systems Inc, Toronto. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-2896(99)00016-1

Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR (2004) Emotional intelligence: theory, findings, and implications. Psychol Inquiry. 15(3):197–215. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1503_02

Petrides KV, Sangareau Y, Farnham A, Frederickson N (2006) Trait emotional intelligence and children’s peer relations at school. Soc Dev 15(3):537–547. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2006.00355.x

Lundqvist D, Flykt A, Öhman A (1998) The Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces-KDEF. CD ROM from Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Psychology section. Karolinska Institute, Solna

Goeleven E, De Raedt R, Leyman L, Verschuere B (2008) The Karolinska directed emotional faces: a validation study. Cognit Emot 22(6):1094–1118. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930701626582

Costarelli V, Demerzi M, Stamou D (2009) Disordered eating attitudes in relation to body image and emotional intelligence in young women. J Hum Nutr Diet 22(3):239–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-277X.2009.00949.x

Zysberg L, Rubanov A (2010) Emotional intelligence and emotional eating patterns: a new insight into the antecedents of eating disorders? J Nutr Educ Behav 42(5):345–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2009.08.009

Foye U, Hazlett DE, Irving P (2019) Exploring the role of emotional intelligence on disorder eating. Eat Weight Disord 24(2):299–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0629-4

Lane AM, Meyer BB, Devonport TJ, Davies KA, Thelwell R, Gil GS et al (2009) Validity of the emotional intelligence scale for use in sport. J Sport Sci Med 8:289–295

Zysberg L, Tell E (2013) Emotional intelligence, perceived control, and eating disorders. SAGE Open 3:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013500285

Zysberg L (2013) Emotional intelligence, personality, and gender as factors in disordered eating patterns. J Health Psychol 19(8):1035–1042. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105313483157

Gardner KJ, Quinton S, Qualter P (2014) The role of trait and ability emotional intelligence in bulimic symptoms. Eat Behav 15(2):237–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.02.002

Hambrook D, Brown G, Tchanturia K (2012) Emotional intelligence in anorexia nervosa: is anxiety a missing piece of the puzzle? Psychiatry Res 200:12–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.05.017

Cohen J (1992) A power primer. Psychol Bull 112:155–159

Markey MA, Vander Wal JS (2007) The role of emotional intelligence and negative affect in bulimic symptomatology. Compr Psychiat 48(5):458–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.05.006

Filaire E, Larue J, Rouvieux M (2010) Eating behaviours in relation to emotional intelligence. Int J Sports Med 32(4):309–315. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1269913

Pettit ML, Jacobs SC, Page KS, Porras CV (2009) An assessment of perceived emotional intelligence and eating attitudes among college students. Am J Health Educ 41(1):46–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2010.10599126

Li Y (2018) Social anxiety and eating disorder risk among Chinese adolescents: the role of emotional intelligence. Sch Ment Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-9257-4

Zavala MA, López I (2012) Adolescentes en situación de riesgo psicosocial ¿Qué papel juega la inteligencia emocional? Behav Psychol 20(1):59–75

Peres V, Corcos M, Robin M, PhamScottez A (2018) Emotional intelligence, empathy and alexithymia in anorexia nervosa during adolescence. Eat Weight Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0482-5

Cuesta C, González I, García LM (2017) The role of trait emotional intelligence in body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms in preadolescents and adolescents. Pers Individ Differ 126:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.12.021

Koch A, Pollatos O (2015) Reduced facial emotion recognition in overweight and obese children. J Psychosomat Res 79(6):635–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.06.005

Wisniewski L, Kelly E (2003) The application of dialectical behavior therapy to the treatment of eating disorders. Cogn Behav Pract 10:131–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1077-7229(03)80021-4

Arlt J, Yiu A, Eneva K, Dryman MT, Heimberg RG, Chen EY (2016) Contributions of cognitive inflexibility to eating disorder and social anxiety symptoms. Eat Behav 21:30–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.12.008

Ciarma JL, Mathew JM (2017) Social anxiety and disordered eating: the influence of stress reactivity and self-esteem. Eat Behav 26:177–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.03.011

Diehl NS, Johnson CE, Rogers RL, Petrie TA (1998) Social physique anxiety and disordered eating: what’s the connection? Addict Behav 23(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4603(97)00003-8

Hinrichsen H, Wright F, Waller G, Meyer C (2003) Social anxiety and coping strategies in the eating disorders. Eat Behav 4(2):117–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1471-0153(03)00016-3

Levinson CA, Rodebaugh TL (2012) Social anxiety and eating disorder comorbidity: the role of negative social evaluation fears. Eat Behav 13(1):27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.11.006

Levinson CA, Rodebaugh TL (2016) Clarifying the prospective relationships between social anxiety and eating disorder symptoms and underlying vulnerabilities. Appetite 107:38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.07.024

Linardon J, Braithwaite R, Cousins R, Brennan L (2017) Appearance-based rejection sensitivity as a mediator of the relationship between symptoms of social anxiety and disordered eating cognitions and behaviors. Eat Behav 27:27–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.10.003

Wonderlich-Tierney AL, Vander Wal JS (2010) The effects of social support and coping on the relationship between social anxiety and eating disorders. Eat Behav 11(2):85–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.10.002

Bydlowski S, Corcos M, Jeammet P, Paternity S, Berthoz S, Laurier C et al (2005) Emotion-processing deficits in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 37(4):321–329. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20132

Kessler H, Schwarze M, Filipic S, Traue HC, Wietersheim J (2006) Alexithymia and facial emotion recognition with eating disorders. Int J Eating Disord 39(3):245–251. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20228

Henderson NJ, Huon GF (2002) Negative affect and binge eating in overweight women. Br J Health Psychol 7:77–87. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910702169376

Johnson SJ, Batey M, Holdsworth L (2009) Personality and health: the mediating role of trait emotional intelligence and work locus of control. Pers Individ Differ 47:470–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.04.025

Salovey P, Hsee CK, Mayer JD (1993) Emotional intelligence and the self-regulation of affect. In: Wegner D, Pennebaker JW (eds) Handbook of mental control. Prentice-Hall, Englewood cliffs NJ, pp 258–277

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have No conflicts of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

This article does not contain any studies performed by any of the authors involving human participants or animals.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The article is part of the Topical Collection on Personality and Eating and Weight Disorders.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Romero-Mesa, J., Peláez-Fernández, M.A. & Extremera, N. Emotional intelligence and eating disorders: a systematic review. Eat Weight Disord 26, 1287–1301 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00968-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00968-7