Abstract

Purpose

We compared parent’s perceived child’s silhouette, and investigated predictors of their dissatisfaction.

Methods

Participants were 4930 mother–child dyads enrolled at a Portuguese birth cohort. Parents’ perceptions of child’s current and desired silhouette was assessed and dissatisfaction with child’s silhouette was defined as the discrepancy between these ratings (current–desired body). Multinomial logistic regressions, adjusted for potential confounders, were performed.

Results

Mothers were more dissatisfied with child’s silhouette, compared to fathers, in all weight categories. Mothers and fathers of girls were more dissatisfied, preferring thinner silhouettes (OR = 2.77, 95% CI 2.19; 3.51 and OR = 2.08, 95% CI 1.18; 3.66, respectively), compared to parents of boys. Lower birth weight increased maternal desire for a heavier child silhouette. Younger (< 20 years) and less educated (≤ 9 years of schooling) mothers were more dissatisfied with their child’s silhouette, preferring heavier children (OR = 1.65, 95% CI 1.10; 2.48 and OR = 1.73, 95% CI 1.42; 2.09, respectively). Parents’ own dissatisfaction was also associated with child’s silhouette dissatisfaction.

Conclusion

Sociodemographic characteristics and parents’ dissatisfaction with their own silhouette influenced their dissatisfaction with child’s silhouette and should be considered when developing obesity interventions.

Level of evidence

Level III, case–control analytic study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Body image can be defined as a “multifaceted psychological experience of embodiment”, influenced by a variety of factors, including individual’s thoughts, beliefs, feelings and behaviors [1]. A way to measure one’s body image is through the disagreement between the perception of current and ideal silhouette, indicating a degree of dissatisfaction. Parents dissatisfaction about their child’s silhouette has been explored in the literature [2,3,4,5], but its effect on child’s health is non-conclusive. It seems plausible to assume that parents’ dissatisfaction with child’s silhouette may serve as a protection against excessive weight. The desire for a thinner child seems to promote the need for preventive strategies, however this recognition seems to occur only when the child has already excessive weight [6, 7], so parents do not take action before the child comes across with weight problems [8]. Evidence also shows the harmful effects of parents’ dissatisfaction with child’s silhouette, such as lower body esteem [9] and dissatisfaction with own weight during childhood [4], weight control behaviors, body dissatisfaction [10], and changes in weight trajectories [2] during adolescence, and increased weight [3] and body dissatisfaction in adulthood [3, 11]. In addition, parents tend to increase restrictive feeding practices aiming to manage weight among school-aged children [5], increasing the risk of disordered eating in childhood [9] and later in life [11]. Given the variety of consequences of parental dissatisfaction with child’s silhouette, there is a critical need to address this issue as a public health concern [12].

Parent’s feedback on child weight may be direct, by engaging in negative comments about their child’s weight or using specific feeding strategies, or indirect, by dieting, through “fat talk” and weight concerns [13]. Maternal own weight dissatisfaction seem to be associated with the dissatisfaction with their child’s silhouette in preschool [2] and school-age years [14] and their own weight concerns may impact the engagement of restrictive feeding practices [15], and increase offspring’s concerns about weight and attention paid to calories during adulthood [3]. Some studies investigated the effect of parents own weight concerns and family weight-talk on later decreased body esteem, increased depressive symptoms [16] and body dissatisfaction [3, 10, 11, 16], and the majority assessed adolescent’s/adult’s perception/recall of their parent’s weight concerns and comments, which may be biased by their own weight concerns. Studies assessing parents actual reported dissatisfaction about their own body are therefore warranted.

It is well documented that health promoting interventions among children are more effective if there is a considerable commitment of both children and their families [17, 18]. As previously emphasized, mothers are generally more influential over the offsprings’ weight perception, eating habits [11] and child’s lifestyle [8]. So, maternal perception of child’s weight and awareness of a potential health problem is essential in order to take the first steps towards weight management and preventive actions [18]. This statement is confirmed in studies showing that a healthy body image may lead to better health outcomes during childhood and young adulthood [4, 19]. Taking into account the great influence of mothers, the majority of studies focus solely on maternal perception of child’s silhouette, and do not assess the father’s perception. Thus, assessing weight perceptions of both parents is warranted in order to make positive health behavior changes in the family [20]. It is important to highlight that a lack of studies evaluated both mother’s and father’s perceptions of child’s silhouette, and did not distinguish the differences between these perceptions [21, 22].

The majority of studies investigated the relation between self-perceived body image during adolescence and binge eating, psychological distress [23] and depressive symptoms [24], and there is a lack of studies that focus on parental dissatisfaction with child’s silhouette, especially using large population-based samples. In light of this, we aimed to assess both mother’s and father’s dissatisfaction with child’s silhouette and, secondly, to investigate factors associated with parents’ dissatisfaction.

Materials and methods

Study population

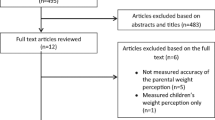

Participants were enrolled in the population-based cohort study Generation XXI. Briefly, mother and child dyads were invited to participate in the study after delivery. The recruitment took place between April 2005 and August 2006, in all public maternities of the metropolitan area of Porto (northern Portugal). At birth, 91.4% of the invited mothers agreed to participate (n = 8647 children and 8495 mothers). Data on demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, lifestyles, anthropometrics, obstetric history and previous personal diseases were collected within 72 h after delivery, in face-to-face interviews, performed by trained interviewers [25, 26]. Generation XXI evaluations were performed at birth and when children were 4 (86% of participation proportion), 7 (80% of participation proportion) and 10-years-old (y) (76% of participation proportion). Currently, the 13 years’ follow-up is ongoing. At each evaluation, all participants are invited and, in addition to child’s information, data of both parents is also collected. Cohort management and maintenance is performed continuously, by contacting participating families by phone and by mail. More details about the recruitment is described elsewhere [25, 26]. Data from baseline and the 7 year follow-up (evaluation from April 2012 until March 2014) was used in this current study. During the follow-ups, information was obtained in face-to-face interviews or, in case the family was not able to participate in person, the evaluation was performed by telephone. The current study included only those parent–child dyads that attended the face-to-face interviews at 7 years (see flowchart in Fig. 1).

Measures

Child’s actual weight status

Child’s weight and height were measured using standard procedures [27]. Participants were weighted in underwear and without shoes, using a digital scale and the measure was recorded to the nearest 0.1 kg. Height was also measured without shoes, using a fixed stadiometer to the nearest 0.1 cm. Child’s Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated and cut-off points for the sex- and age specific BMI z-scores (BMIz) were created, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). ‘Underweight’ was defined as z-score < − 2 standard deviations (SD), ´normal weight’ as z-score ≥ − 2SD and < + 1SD, ´overweight’ as z-score ≥ + 1 and < + 2 and ‘obesity’ as z-score ≥ + 2SD [28].

Perception of and satisfaction with silhouettes

Mother’s and father’s perception of child’s silhouette was assessed using the Children’s Figure Rating Scale [29]. They were asked to identify, within nine gender-specific silhouettes of increasing size, ranging from very thin (1) to severely obese (9), which silhouette represented their child’s current and desired body. Satisfaction with child’s silhouette was assessed by the discrepancy between the two ratings (current–desired silhouette), as described in previous studies [2, 5, 14, 30, 31]. Differences equal to zero indicated that mothers/fathers were satisfied with their child’s current silhouette. Negative differences indicated that the mother/father desired a larger silhouette for their child (i.e. a heavier weight) and positive differences indicated that mothers/fathers desired a thinner or lower weight for their child. Parent’s degree of satisfaction with child’s silhouette was categorized into ‘satisfied’ with child’s silhouette (reference category), ‘prefers heavier silhouette’, and ‘prefers thinner silhouette’. Parents’ satisfaction with their own body was evaluated using the Stunkard’s silhouette scale [32], and their dissatisfaction with their own silhouette was assessed using the same method as described above.

Co-variates

The current study used parents’ age at baseline (described as a continuous variable and categorized into < 20, 20–29 and ≥ 30 years), educational level (recorded by complete years of schooling and categorized into ≤ 9, 10 to 12 and > 12 schooling years) and household income (≤ 1000, 1001–1500 and > 1500 euros per month). Weight and height were measured (without shoes), BMI was calculated and the WHO cut-off points were used for weight status classification, as follows: < 18.5 kg/m2 for ‘Underweight’, between ≥ 18.5 kg/m2 and < 25 kg/m2 for ‘Normal weight’, between ≥ 25 kg/m2 and < 30 kg/m2 for ‘Overweight’ and ≥ 30 kg/m2 for ‘Obesity’ [33].

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses were performed for categorical variables (frequency distribution) and continuous variables (means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges). Normal distributed variables were compared using Student’s t tests, and those not normally distributed were compared using Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests. Multinomial logistic regression models were run to compute odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) estimating the association between mother’s and father’s dissatisfaction with child’s silhouette (satisfaction with child’s silhouette was considered the reference category) and family characteristics. Models were adjusted for potential confounders, according to literature review. In the models that assessed mother’s dissatisfaction with child’s silhouette, maternal [31] and child age [6], maternal education [4, 7, 31] and child sex [6] were included in the Adj. 1 OR, and Adj. 2 OR was adjusted for Adj. 1 OR plus child BMIz [7, 8]. In the father’s multinomial regression models, paternal variables were included for adjustment (i.e. father’s age and education), plus child’s age and sex in Adj. 1 OR, and Adj. 2 OR was additionally adjusted for child BMIz.

A sensitivity analysis was performed only among children with overweight or obesity, in order to explore associated factors with maternal satisfaction with child’s silhouette. Thus, logistic regression models were performed among those children and, in this specific group, maternal satisfaction with child’s silhouette was considered the risk category.

Statistical significance was set in 5% and data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software (IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

Results

More than a third of children and mothers and almost 60% of fathers were categorized with overweight or obesity. Family income was ≤ 1000 euros per month in 36.9% of households and nearly half of the children did not have siblings at 7 years. Forty percent of mothers reported some degree of dissatisfaction with child’s silhouette, either preferring a heavier (24.5%) or a thinner (15.6%) silhouette for their child. Twenty-one percent of the fathers preferred heavier silhouettes for their children and nearly 16% preferred a thinner child (Table 1).

Among the 3149 normal weight children, 37% of mothers were dissatisfied with child´s silhouette, and the vast majority preferred a heavier child (Fig. 2). Almost 74% of mothers whose children had overweight were satisfied with child’s current silhouette and, among children with obesity, almost a third of mothers were satisfied with child’s silhouette. Among fathers, a greater percentage showed to be satisfied with their child’s silhouette, in the normal weight and obese categories (66.8% and 34%, respectively), compared to mother’s perceptions (Fig. 2).

Mothers’ (a) and fathers’ (b) satisfaction with child’s silhouette, according to child’s measured body weight status. BMI categories were created based on the WHO growth references [28]. Underweight was defined as < − 2 SD, Normal weight as ≥ − 2 and < + 1SD, Overweight ≥ + 1 and < + 2 and Obesity > + 2SD. Mother’s and father’s perceptions of child’s silhouette was assessed through the Children’s Figure Rating Scale [29]: a represents mother’s perceptions (n = 4930) and b represents father’s perception of child’s silhouette (n = 1844)

Table 2 shows the associations between child and mother characteristics and maternal dissatisfaction with child’s silhouette. In the multivariate analysis (adj. 2 OR was considered as the final model), mothers were more likely to desire thinner girls than thinner boys (OR = 2.77, 95% CI 2.19; 3.51). Mothers of low birth weight children showed 53% greater odds in desiring heavier children than those whose children were born normal weight, independently of child’s BMI at 7 years (OR = 1.53, 95% CI 1.15; 2.05). Younger and less educated mothers showed a higher preference for heavier children (< 20 vs. ≥ 30 years: OR = 1.65, 95% CI 1.10; 2.48 and ≤ 9 vs. > 12 years of education OR = 1.73, 95% CI 1.42; 2.09), and lower preference for thinner ones. Mothers with overweight and obesity showed a preference for thinner children (adj. 1 OR = 1.72, 95% CI 1.42; 2.09 and OR = 1.95, 95% CI 1.49; 2.55, respectively), however this association was dependent of child’s BMI at 7 years. Maternal dissatisfaction with her own silhouette (both desiring lower or heavier silhouettes for herself) was positively associated with the desire for heavier children (OR = 1.67, 95% CI 1.38; 2.01 and OR = 2.47, 95% CI 1.78; 3.42, respectively).

Similarly to mothers, fathers showed greater likelihood to change their perception of child’s silhouette according to child sex, desiring thinner girls more than thinner boys, independently of child weight status (OR = 2.08, 95% CI 1.18; 3.66). Fathers also showed 4.6 times greater odds of desiring heavier children if they were also dissatisfied with their own silhouette (i.e. also desiring heavier silhouettes for themselves) (OR = 4.60, 95% CI 2.12; 10.01). No other significant associations were found in the father’s sample (Table 3).

In a sensitivity analysis, we restricted the study sample to those children with overweight/obesity (n = 1759), and assessed the association of the study factors with the mothers’ satisfaction with child’s silhouette (considered as the risk category due to the possible body weight distortion). We were able to find that mothers of boys with excessive weight were more likely to be satisfied with their child’s silhouette (OR = 1.18, 95% CI 1.05; 1.32). Less educated mothers (i.e. ≤ 9 years and 10-12 years vs >12 years of schooling) were also more likely to be satisfied with their child’s silhouette, even if their child was overweight or obese. Mothers with obesity (i.e. BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) had two times greater odds in being satisfied with their child’s excessive weight. Finally, mothers dissatisfied with their own body (those that preferred a leaner silhouette for themselves) were less likely to be dissatisfied with their child’s silhouette (OR = 0.71, 95% CI 0.53; 0.95) (Table 4).

Discussion

The current study investigated mother’s and father’s perceptions of their child’s silhouette and the predictors of parents’ body image dissatisfaction, among their 7-year-old children. Mothers showed a greater dissatisfaction with child’s silhouette, compared to fathers, in all child weight categories. A variety of factors were associated with maternal dissatisfaction with their child’s silhouette, namely female sex, children with low birth weight, low maternal age and education, and mother’s dissatisfaction with her own silhouette. Fathers, on the other hand, showed similar associations with child’s silhouette dissatisfaction, being more dissatisfied with their daughter’s bodies and if they were dissatisfied with their own silhouettes.

Almost three quarters of parents of children with overweight showed satisfaction with child’s silhouette. Usually, parents are more likely to misclassify their child towards the healthy weight category [34, 35], and this is based on predefined concepts, perceptions and beliefs [6]. As prevalence of childhood obesity increases, so does the number of parents who incorrectly identify their child’s weight status as normal weight and are not concerned about their child’s excessive weight. This may be due to the development of social norms that arise from self-comparisons with others, providing support to the idea that what is common, becomes normal [7, 35, 36]. Parents seem to be unaware of what overweight looks like in children, defining their child as healthy if it is, for example, an active child, with good self-esteem and that is not teased by peers or other family members [35]. Evidence from qualitative studies showed that parents believed that their child will eventually “outgrow” their excessive weight, saw excessive weight as “cute and healthy”, spoke of obesity as a problem that may affect child’s health in the future, but not in the present [37] and showed a lack of trust in the measure used to classify their child as overweight [38]. These believes and thoughts may impose important barriers in the engagement of weight control interventions [18].

The desire for heavier/thinner silhouettes was found to be gender-specific, as seen by the nearly three times greater odds of desiring thinner silhouettes among mothers of girls, and nearly 50% lower odds among mothers of girls preferring heavier weight, both compared to satisfied mothers and mothers of boys (Table 2). In the sensitivity analyses performed (Table 4), we were able to observe that among boys with overweight/obesity, there is an increased odds for mother’s satisfaction with their child’s silhouette. This might be explained by the social desirability for a bulkier, more musculous body for boys and a thinner and smaller body size for girls [39, 40] and parental body size attitudes correspond to these social stereotypes already at young ages [41]. Studies have emphasized the harmful effects of parental dissatisfaction with child’s body, with unsatisfied parents particularly expressing the desire for an appearance-ideal by using negative comments towards their children, which may lead to body image dissatisfaction, disordered [11], restraint, and external eating [9], depressive symptoms and weight gain in young adulthood [16].

Mothers of children with low birth weight also showed 53% greater odds in desiring heavier children, and this was independent of confounders. This finding is in line with studies of mothers of preschoolers, which showed that lower birth weight is associated with greater concerns about child eating behaviors, child weight [15] and pressuring feeding practices [42]. It is intuitive that parents of small infants will have more concerns about their child weight gain during infancy, changing, consequently, their feeding practices, as seen in previous studies [15, 42].

Younger mothers (< 30 years) were more likely to desire heavier children, compared to older mothers, and this might be explained by the lower knowledge and experience regarding child’s health [43], and the greater believe that a heavier child is also a healthier child [37]. Other sociodemographic variables, such as maternal education showed similar effects; mothers with lower educational levels (≤ 9 years of schooling) reported more often the desire for heavier children. We also found that less educated mothers have greater weight satisfaction among children with overweight/obesity. A study using a qualitative approach showed that low income mothers expressed little concern about child’s excessive weight and attributed body weight to genetic heredity and not to environmental factors [44], and seem to underestimate more frequently their child’s weight compared to higher income families [7, 45]. Duchin et al. (2013) also found a relation between higher maternal and child body image dissatisfaction and lower family’s socioeconomic status (SES) [40], and suggested that, as SES has already been linked to childhood obesity [46], the association between SES and body weight could be mediated in part by the body image perception and reflects the traditional concept that associates improved health with heavier weight as a result of better economic conditions [40]. This associations may also be explained by the less knowledge about the health consequences of childhood obesity in families with lower SES, as described in a recent study [45].

On the other hand, the Westernized ideal of thinness, under the perspective that wealthier children would be thinner [40], seems to be more influential among mothers with excessive weight (≥ 25 kg/m2), as shown by the greater odds of those mothers to desire leaner children in the current sample. Mothers in the heavier weight range, compared to those with normal weight, may have an enhanced fear of their child becoming overweight as well. The higher concern of the child becoming overweight among heavier parents may reflect that these parents are aware of their personal experiences of hardships related to excessive weight, therefore increasing their concern about their child in becoming overweight [47]. However, the effect of mother’s BMI and dissatisfaction with child’s silhouette is influenced by child BMIz, with associations not maintaining their significance after further adjusting the model. Interestingly, among those children with excessive weight, mothers with obesity were two times more satisfied with their child’s silhouette. This reflects the great interaction between these two characteristics and shows that mothers with obesity may also be unaware or even concerned with their child’s weight problem. The failure of mothers with obesity in correctly identifying their child with excessive weight was also observed in a large Irish cohort study, which explained that probably these mothers may have a higher threshold in the definition of overweight [48], which can be targeted in future health literacy programs.

Greater maternal dissatisfaction with her own silhouette (either preferring higher or lower weight) was significantly and positively associated with maternal dissatisfaction with their child’s silhouette. In particular, mothers who desired to gain weight were also more likely to want their child to also gain weight, whereas mothers who desired to lose weight were more likely to want their child to gain weight in the fully adjusted models. This is in line with the weak, but positive correlation between maternal dissatisfaction with her own silhouette and dissatisfaction with child’s silhouette (Spearman’s rho = 0.07, p < 0.001) in the current sample (data not shown), and corroborates with a previous study with parents of school-aged children [14]. Mother’s own weight concerns were also associated with early concerns about their child’s eating behaviors and weight in a study with children under 2 years of age [15]. Maternal dissatisfaction with her own silhouette may lead to the adoption of strategies meant to control their child’s body weight [5, 15] and may lead to unintended consequences, besides worsening the already existing obesity, as stated above.

Research on parental dissatisfaction with child’s silhouette is commonly limited to the perceptions of the mother [49], thus we examined also father’s perceptions and associated factors in the current study. We found that fathers showed greater satisfaction with child excessive weight, compared to mothers (34% of fathers were satisfied with child’s silhouette in the obesity weight category—Fig. 2). In general, we found less consistent associated factors with the dissatisfaction with child’s silhouette in the father’s sample, suggesting that the influence of mothers on child eating habits [11], lifestyle [8] and weight perception is stronger compared to father’s influence. However, we were still able to find that fathers were also more likely to desire thinner silhouettes for girls (OR = 2.08) and prefer heavier silhouettes for their children, independently of confounders, if they also desired heavier silhouettes for themselves (OR = 4.60).

Our study has some limitations that need to be addressed. First, given the cross-sectional nature of this study, results cannot be interpreted as causal relationships. Also, these findings should not be generalized to populations with other cultural backgrounds, because of the different influence of a variety of factors that could contribute to parents’ perception and satisfaction with child’s silhouette. It is also important to highlight that parents’ body satisfaction was measured on a single time point, and this perception may not be consistent over time, especially among children. Finally, there are limitations related to BMI, seen as an imprecise measure of adiposity, but it is one of the best measures for large scale studies.

The strengths of the current study include the use of a validated silhouette scale for children [29]. A variety of techniques have been used to assess body image perception and body image distortion, such as questionnaires and figural scales, being the latter the most commonly adopted [2, 5, 21] and reliable to assess silhouette perceptions [50]. We used a large sample size, with available standardized measures of weight and height instead of reported values, and with parents’ reports of actual concern about their own weight. To our knowledge, this is the first study that investigated the factors associated with parents’ satisfaction with child’s silhouette in a large sample of Portuguese parent and child dyads. In addition, the inclusion of fathers’ perception of child’s silhouette is also a strength and should be explored in more detail in future studies.

Given the alarming increase of childhood obesity worldwide, it is important to also consider their parents body dissatisfaction as a factor that is identifiable, modifiable, and clearly underutilized [12] in family-centered interventions to control childhood obesity and other harmful consequences in child’s life [51]. The social stigma and blame attached to parents of children with excessive weight needs to be addressed in these interventions so that the family is able to manage this health condition together [37]. The current findings highlight the importance of effective preventive interventions for mothers and fathers of girls, with lower maternal age, education, and that are dissatisfied with their own weight, in order to create an environment that fosters an accurate and healthy body image.

What is already known on this subject?

Maternal perception of child’s body and its dissatisfaction has been linked to harmful consequences, such as weight gain in adolescence and adulthood, use of restrictive feeding and disordered eating.

What your study adds?

First study that investigated the factors associated with both mothers’ and fathers’ dissatisfaction with child’s silhouette in a large sample of Portuguese parent and child dyads.

References

Cash TF (2004) Body image: past, present, and future. Body Image 1:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00011-1

Duchin O, Marin C, Mora-Plazas M, Villamor E (2016) Maternal body image dissatisfaction and BMI change in school-age children. Public Health Nutr 19:287–292. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980015001317

Wansink B, Latimer LA, Pope L (2017) “Don’t eat so much:” how parent comments relate to female weight satisfaction. Eat Weight Disord 22:475–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0292-6

Wong Y, Chang YJ, Lin CJ (2013) The influence of primary caregivers on body size and self-body image of preschool children in Taiwan. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 22:283–291. https://doi.org/10.6133/apjcn.2013.22.2.05

Webb HJ, Haycraft E (2019) Parental body dissatisfaction and controlling child feeding practices: a prospective study of Australian parent-child dyads. Eat Behav 32:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.10.002

Black JA, Park M, Gregson J et al (2015) Child obesity cut-offs as derived from parental perceptions: cross-sectional questionnaire. Br J Gen Pract 65:e234–e239. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp15X684385

Binkin N, Spinelli A, Baglio G, Lamberti A (2013) What is common becomes normal: the effect of obesity prevalence on maternal perception. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 23:410–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2011.09.006

Warschburger P, Kröller K (2012) Childhood overweight and obesity: Maternal perceptions of the time for engaging in child weight management. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-295

Rodgers RF, Wertheim EH, Damiano SR, Paxton SJ (2020) Maternal influences on body image and eating concerns among 7- and 8-year-old boys and girls: cross-sectional and prospective relations. Int J Eat Disord 53:79–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23166

Abdalla S, Buffarini R, Weber AM et al (2020) Parent-related normative perceptions of adolescents and later weight control behavior: longitudinal analysis of cohort data from Brazil. J Adolesc Heal 66:S9–S16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.09.007

Chng SCW, Fassnacht DB (2016) Parental comments: Relationship with gender, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating in Asian young adults. Body Image 16:93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.12.001

Bucchianeri MM, Neumark-Sztainer D (2014) Body dissatisfaction: an overlooked public health concern. J Public Ment Health 13:64–69. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-11-2013-0071

Claydon EA, Zullig KJ, Lilly CL et al (2019) An exploratory study on the intergenerational transmission of obesity and dieting proneness. Eat Weight Disord Stud Anorexia Bulim Obes 24:97–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0478-1

Pedroso J, Toral N, Gubert MB (2018) Maternal dissatisfaction with their children’s body size in private schools in the Federal District, Brazil. PLoS ONE 13:7–9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204848

Markey CN, Markey PM, Schulz JL (2012) Mothers’ own weight concerns predict early child feeding concerns. J Reprod Infant Psychol 30:160–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2012.693152

de León-Vázquez CD, Villalobos-Hernández A, Rivera-Márquez JA, Unikel-Santoncini C (2019) Effect of parental criticism on disordered eating behaviors in male and female university students in Mexico city. Eat Weight Disord 24:853–860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0564-4

Golley RK, Hendrie GA, Slater A, Corsini N (2011) Interventions that involve parents to improve children’s weight-related nutrition intake and activity patterns—what nutrition and activity targets and behaviour change techniques are associated with intervention effectiveness? Obes Rev 12:114–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00745.x

Tompkins CL, Seablom M, Brock DW (2015) Parental perception of child’s body weight: a systematic review. J Child Fam Stud 24:1384–1391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9945-0

van den Berg P, Neumark-Sztainer D (2007) Fat ′n happy 5 years later: is it bad for overweight girls to like their bodies? J Adolesc Heal 41:415–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.06.001

Davis AM, Canter KS, Pina K (2019) The importance of fathers in pediatric research: these authors are on to something important. Transl Behav Med 9:570–572. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibz053

Hernandez RG, Cheng TL, Serwint JR (2010) Parents healthy weight perceptions and preferences regarding obesity counseling in preschoolers: pediatricians matter. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 49:790–798. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922810368288

Oude Luttikhuis HGM, Stolk RP, Sauer PJJ (2010) How do parents of 4- to 5-year-old children perceive the weight of their children? Acta Paediatr Int J Paediatr 99:263–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01576.x

Mitchison D, Hay P, Griffiths S et al (2017) Disentangling body image: the relative associations of overvaluation, dissatisfaction, and preoccupation with psychological distress and eating disorder behaviors in male and female adolescents. Int J Eat Disord 50:118–126. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22592

Solomon-Krakus S, Sabiston CM, Brunet J et al (2017) Body image self-discrepancy and depressive symptoms among early adolescents. J Adolesc Heal 60:38–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.08.024

Alves E, Correia S, Barros H, Azevedo A (2012) Prevalence of self-reported cardiovascular risk factors in Portuguese women: a survey after delivery. Int J Public Health 57:837–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-012-0340-6

Larsen PS, Kamper-Jørgensen M, Adamson A et al (2013) Pregnancy and birth cohort resources in Europe: a large opportunity for aetiological child health research. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 27:393–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppe.12060

Gibson RS (2005) Principles of nutritional assessment, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Dunedin

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E et al (2007) Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ 85:660–667

Tiggemann M, Wilson-Barrett E (1998) Children’s figure ratings: Relationship to self-esteem and negative stereotyping. Int J Eat Disord 23:83–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199801)23:1<83:AID-EAT10>3.0.CO;2-O

Bulik C, Wade T, Heath A et al (2001) Relating body mass index to figural stimuli: population-based normative data for Caucasians. Int J Obes 25:1517–1524. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0801742

Aparício G, Cunha M, Duarte J et al (2013) Nutritional status in preschool children: current trends of mother’s body perception and concerns. Atención Primaria 45:194–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0212-6567(13)70022-2

Stunkard A, Sorensen T, Schulsinger F (1983) Use of the Danish adoption register for the study of obesity and thinness. The genetics of neurological and psychiatric disorders. Raven Press, New York, pp 115–120

World Health Organization (WHO) (1999) Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: report of a WHO consultation. WHO technical report series; 894, 252 p

Leppers I, Tiemeier H, Swanson SA et al (2017) Agreement between weight status and perceived body size and the association with body size satisfaction in children. Obesity 25:1956–1964. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21934

Mareno N (2014) Parental perception of child weight: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 70:34–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12143

Duncan DT, Hansen AR, Wang W et al (2016) Change in misperception of child’s body weight among parents of American preschool children. Child Obes 11:384–393. https://doi.org/10.1089/chi.2014.0104

Eli K, Howell K, Fisher PA, Nowicka P (2014) “A little on the heavy side”: a qualitative analysis of parents’ and grandparents’ perceptions of preschoolers’ body weights. BMJ Open 4:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006609

Gillison F, Beck F, Lewitt J (2014) Exploring the basis for parents’ negative reactions to being informed that their child is overweight. Public Health Nutr 17:987–997. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980013002425

Manios Y, Moschonis G, Karatzi K et al (2015) Large proportions of overweight and obese children, as well as their parents, underestimate children’s weight status across Europe. the ENERGY (EuropeaN Energy balance Research to prevent excessive weight Gain among Youth) project. Public Health Nutr 18:2183–2190. https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898001400305X

Duchin O, Mora-Plazas M, Marin C et al (2013) BMI and sociodemographic correlates of body image perception and attitudes in school-aged children. Public Health Nutr 17:2216–2225. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980013002309

Damiano SR, Gregg KJ, Spiel EC et al (2015) Relationships between body size attitudes and body image of 4-year-old boys and girls, and attitudes of their fathers and mothers. J Eat Disord 3:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-015-0048-0

Fildes A, van Jaarsveld CHM, Llewellyn C et al (2015) Parental control over feeding in infancy. Influence of infant weight, appetite and feeding method. Appetite 91:101–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.04.004

Bornstein MH, Cote LR, Haynes OM et al (2010) Parenting knowledge: experiential and sociodemographic factors in European American mothers of young children. Dev Psychol 46:1677–1693. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020677

Jain A, Sherman SN, Chamberlin DLA et al (2001) Why don’t low-income mothers worry about their preschoolers being overweight? Pediatrics 107:1138–1146. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.107.5.1138

Ling J, Stommel M (2019) Parental and self-weight perceptions in US children and adolescents, NHANES 2005–2014. West J Nurs Res 41:42–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945918758274

Wang Y, Lim H (2012) The global childhood obesity epidemic and the association between socio-economic status and childhood obesity. Int Rev Psychiatry 24:176–188. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2012.688195

Peyer KL, Welk G, Bailey-Davis L et al (2015) Factors associated with parent concern for child weight and parenting behaviors. Child Obes 11:269–274. https://doi.org/10.1089/chi.2014.0111

Queally M, Doherty E, Matvienko-Sikar K et al (2018) Do mothers accurately identify their child’s overweight/obesity status during early childhood? Evidence from a nationally representative cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 15:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0688-y

Tatangelo G, McCabe M, Mellor D, Mealey A (2016) A systematic review of body dissatisfaction and sociocultural messages related to the body among preschool children. Body Image 18:86–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.06.003

Gardner RM, Brown DL (2010) Body image assessment: a review of figural drawing scales. Pers Individ Dif 48:107–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.08.017

Lydecker JA, Cunningham PM, O’Brien E, Grilo CM (2019) Parents’ perceptions of parent-child interactions related to eating and body image: an experimental vignette study. Eat Disord. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2019.1598767

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the families enrolled in the study cohort for their kindness, all members of the research team for their enthusiasm and perseverance and the participating hospitals and their staff for their help and support. We also acknowledge the support from the Epidemiology Research Unit (UID-DTP/04750/2013; POCI-01-0145-FEDER-006862).

Funding

Generation XXI was funded by the Health Operational Programme–Saúde XXI, Community Support Framework III and the Regional Department of Ministry of Health. This study was supported through FEDER from the Operational Programme Factors of Competitiveness–COMPETE and through national funding from the Foundation for Science and Technology–FCT (Portuguese Ministry of Education and Science) under the projects “Appetite regulation and obesity in childhood: a comprehensive approach towards understanding genetic and behavioural influences” (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-030334; PTDC/SAU-EPI/30334/2017); “Appetite and adiposity–evidence for gene-environment interplay in children” (IF/01350/2015); and through Investigator/Scientific Employment Stimulus Contracts (IF/01350/2015–A.O.; CEECIND/01793/2017–A.H.). It had also support from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Portugal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SW was responsible for study concept, data analysis and interpretation; drafting of the manuscript and final approval of the version to be published. AH was responsible for critical revision of the manuscript, and final approval of the version to be published. AO was co-responsible for study concept; interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript, and final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interests relevant to this article to disclose.

Ethical approval

Generation XXI was approved by the University of Porto Medical School/ S. João Hospital Centre Ethics Committee and by the Portuguese Data Protection Authority. All the phases of the study complied with the Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

A written informed assent from the parents (or legal substitute) and an oral consent from the children were obtained in each evaluation.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Warkentin, S., Henriques, A. & Oliveira, A. Parents’ perceptions and dissatisfaction with child silhouette: associated factors among 7-year-old children of the Generation XXI birth cohort. Eat Weight Disord 26, 1595–1607 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00953-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00953-0