Abstract

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity is soaring all over the world, and Italy is reaching the same pace. Similar to other countries, the Italian healthcare system counts on a three-tier model for obesity care, and each region has freedom in the implementation of guidelines. No national record is currently available to monitor the actual situation throughout the country.

Purpose

To provide a report of the current status on the availability of specialized public obesity care services in Italy.

Methods

Regional prevalence of obesity was extrapolated from publicly available data. Data on facilities for the management of obesity were retrieved from records provided by national scientific societies. Whenever possible, data was verified through online research and direct contact.

Results

We report a north–south and east–west gradient regarding the presence of obesity focused facilities, with an inverse correlation with the regional prevalence of obesity (R = 0.25, p = 0.03). Medical-oriented centers appear homogeneous in the multidisciplinary approach, the presence of a bariatric surgery division, the availability of support materials and groups, with no major difference on follow-up frequency. Surgery-oriented centers have a more capillary territorial distribution than the medically oriented, but not enough data was retrieved to provide a thorough description of their characteristics.

Conclusion

Obtaining a clear picture of the situation and providing consistent care across the country is a challenging task due to the decentralized organization of regions. We provide a first sketch, reporting that the model is applied unevenly, and we suggest feasible actions to improve the situation in our country and elsewhere.

Level of evidence

Level V, narrative review.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes mellitus, are responsible for more than 70% of early deaths worldwide, representing the main cause of mortality and premature disability [1]. Obesity, a major risk factor for several NCDs and an NCD itself, is associated with a reduction in life expectancy of 5–20 years depending on the severity of the condition and the presence of complications [2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), obesity represents one of the main public health issues in the world. We are nowadays facing a global epidemic, which is spreading in many countries and which can, in the absence of immediate action, have a severe impact in the coming years [1].

In Italy, over 10% of the adult population is obese and over a third is overweight [3] with similar numbers among children [4], and the prevalence of obesity having almost tripled in the past 40 years [5]. There is a North–South gap, where southern and insular regions have the highest prevalence of adults with obesity as opposed to the north and center [3, 5]. A less investigated east–west gradient is also present, with regions on the Tyrrhenian coast being generally less affected that those on the Adriatic coast (Fig. 1a).

It has been estimated that by 2050, Italians will live on average 2.7 years less because of being overweight. Overweight will represent 9% of health costs, higher than the average of other countries. In the labor market, production will decrease by an amount equal to 571,000 full-time workers per year due to being overweight. Overall, this means that being overweight will reduce Italian Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 2.8%. To cover these costs, each Italian will pay 289 € of additional taxes per year [6].

Changes in eating behavior and increasingly sedentary lifestyle are majorly involved in the upward trend in obesity, but several other factors might be taken into account such as endocrine disruptors, epigenetics, infections, increased maternal age, medications, all of these possibly contributing to geographical variations [7, 8].

To effectively face the obesity epidemic, Italy has implemented a series of policies, including guidelines promoting physical activity and a healthy dietary pattern, nutritional labels for foods to be placed on the back of food packages and educational policies in schools. However, such epidemic is yet to be tackled in Italy and all over the world. Communication policies, including mandatory packaging labeling, advertising regulation and educational campaigns, could prevent 144,000 non-communicable diseases by 2050, save 62 million € a year in health care spending, and increase the employment and productivity of 6000 full-time workers per year. Moreover, a 20% reduction in calories in foods high in sugar, salt, calories and saturated fats could prevent 688,000 NCDs by 2050, save 278 million €/year in healthcare costs, and increase employment and productivity of 18,000 full-time workers per year [6]. However, although prevention is the primary weapon long term, once the disease has manifested it becomes necessary to engage in actions towards the diagnosis and treatment of complications [9].

To date, there is no thorough record regarding the network of obesity related facilities in Italy. We herein describe what are the characteristics of the model aimed at taking charge of patients suffering from obesity in our country, reporting data on what the reality of our public healthcare system is relative to this.

The Italian National Healthcare System

The Italian National Healthcare System (Sistema Sanitario Nazionale, SSN) was born in 1978 as “a complex of functions, structures, services and activities intended to promote, maintain and recover the physical and mental health of the whole population”, and it has its roots in the Italian Constitution, art. 32, which states that the individual’s right to health is inviolable and absolute [10, 11].

To cope with intervened financial problems, the SSN was reorganized in the early 90 s, turning from a concept of unlimited and unconditional support (Welfare State) to that of public assistance in which the social and healthcare expenses had be proportionate to the actual revenue, no longer solely relating to the extent of the needs. More autonomy and power were attributed to the Regions, and corporate local health units were introduced with the aim of guaranteeing uniform and essential levels of care to all citizens. To provide proper healthcare together with containing expenses, the Essential Assistance Levels (LEA) were born, procedures that the SSN guarantees throughout the national territory for free or upon prescription charge, financed with public resources. The Regions, with their own resources and in full autonomy, could then guarantee additional services on top of those included in the LEA [12].

It became progressively central not only to cure acute conditions, but also to prevent and maintain good health throughout life, intervening on the main modifiable risk factors of disease, investing in early diagnosis and treating chronic diseases. For some of these, identified according to clinical severity criteria, degree of disability and treatment costs, the SSN provides the opportunity to be exempted from prescription charges for certain services aimed at monitoring the disease and preventing complications or further aggravation.

Despite obesity being a disabling chronic disease leading to several complications that cause a significant reduction in both life expectancy and quality, the SSN does not yet include it in the list of conditions qualifying for exemption from prescription charges. Moreover, the only pharmacological therapies approved for the treatment of obesity in Italy are not reimbursed by the SSN, so, despite the recognized efficacy [13], their effective use by obese patients is discouraged by the prohibitive cost (approximately 150 €/month of the Bupropione/Naltrexone combination and 300€/month of Liraglutide 3 mg).

Obesity treatment within the Italian national healthcare system: the model

The most important scientific societies involved in the study of obesity recommend the presence of a network involving the general practitioner (GP), the pediatrician (PED) and more complex organizations guaranteeing structured interventions for patients with complications through a multidisciplinary approach [14]. An effective framework should delineate consistent diagnostic and therapeutic pathways for specific pathologies and provide a health organization that can offer the best care according to the most appropriate procedures. Multiple-tier assistance is recommended, and the Italian model, that provides three levels of assistance, GP/PED, Spoke, and Hub will be briefly described below.

The GP/PED takes charge of the patient with obesity delivering first care. Based on the symptoms and the medical history, he or she prescribes the appropriate diagnostic investigations, defining the treatment and the timing of follow-ups. However, the first level of assistance is characterized by shortcomings linked to the lack of training towards a disease that requires multidisciplinary therapeutic interventions and skills that can hardly find a synthesis in the knowledge of a single professional, not considering the overwhelming commitments that GPs and PEDs face every day [15]. Hence, the role of second-tier specialized centers, the Spokes, becomes vital, especially for the most complicated cases. When the patient has morbid obesity or major complications, or anyways when the case is deemed to be too complex, the patient is, therefore, directed to a second-level facility.

At the Spoke, a specialized public or accredited private out-patient clinic located in hospitals or local general practices, low to medium complexity diagnosis and treatment paths are managed independently, simple therapeutic paths established, directing, where appropriate, patients towards prevention and education courses aimed at promoting healthy behaviors. In case of high complexity, the patient is addressed to specialized, third-level centers, the Hubs.

A Hub is a hospital facility capable of autonomously managing diagnosis and treatment paths for patients with morbid obesity and several complications. It is equipped, among others, with a diagnostic laboratory with advanced technology including molecular and genetic diagnostics, bariatric surgery, and an endoscopy service for the positioning of medical devices for weight loss. Furthermore, it guarantees access to tailored therapeutic pathways based on nutrition and physical education, that take into account the overall dynamics of the individual and the family, the age, presence and severity of complications, family history as well as psychological, cultural and socioeconomic factors. Finally, it ensures the presence of the following specialist skills within the local multidisciplinary team: nutrition, endocrinology, genetics (for pediatric patients), psychology, cardiology, and pneumology. Physical and sports medicine professionals must be available but can be in affiliated practices. The team is usually led by an endocrinologist, nutritionist, internal medicine physician or bariatric surgeon [16].

With regional differences, a third-level facility for adult patients admits those with morbid obesity aged ≥ 15 years and it counts ≥ 3000 visits/year and ≥ 50 bariatric surgery procedures/year. Pediatric Hubs admit patients aged 14 or less, and count ≥ 1000 visits/year with ≥ 15 bariatric surgery procedures/year [17].

Methods

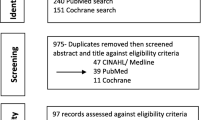

Regional prevalence of obesity was extrapolated from publicly available data [3]. Records regarding the management of weight excess in primary care and classification of second- and third-level facilities based on the Spoke and Hub concept could not be retrieved. Data relative to centers specialized in obesity care were elaborated from the database and/or rerecords made available by the following scientific societies: the Italian Society of Obesity (SIO) [18], the Italian Society of Obesity Surgery (SICOB) [19], the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) [20]. Cumulative data regarding medically oriented facilities takes into account only centers that had these available either through direct contact or scientific society retained records (94.5% of the total). Specifically, no quantitative data was retrieved on 5 centers that were EASO, but not SIO affiliated. Most data derive from subjective evaluations voluntarily provided by the chiefs of SIO affiliated centers in the form of a filled questionnaire. Conversely, no data was retrieved other than location and affiliation type regarding surgically oriented (SICOB) centers. Whenever possible, data was verified through online research and direct contact. Cross-check of SIO/EASO and SICOB centers location and affiliation confirmed that 44% SIO/EASO centers were also SICOB affiliated. To facilitate the reading of our analysis these were counted twice, once as medical and once as surgical. A list of purely residential facilities was not available; therefore, data were based on manual research and authors’ knowledge.

Results

Northern Italy extends for 120,260 km2, with an average population density of 230.74 inhabitants/km2; central Italy extends for 58,052 km2, with a density of 207.87/km2; southern and insular Italy extends for 123,024 km2 and is characterized by lower density (167.19/km2). The distribution of centers dedicated to the treatment of obesity varies according to the geographical area of the country (Fig. 1a). SIO and EASO accredited centers are medically oriented, whereas SICOB accredited centers have a focus on bariatric surgery. Although the available data is not exhaustive given the absence of records relative to non-accredited obesity centers, it provides an overall picture of the current status.

EASO provides accreditation criteria that, rather than concentrating on high number of treated patients, are based on top quality standards with a specific focus on multidisciplinary care and presence of links to the territory [21]. SIO has not yet provided accreditation criteria but follows the same pathway as EASO. There are 38 medically oriented obesity centers that are SIO and/or EASO affiliated in Italy: 21 are located in the north (55.3%), 9 in the center (23.7%) and 8 in the south and the islands (21%). Most feature a bariatric surgery unit, with only a few relying on an external unit. 3/38 specifically deal with pediatric obesity; more than a half (63.16%) addresses both adults and children, and 12/38 (31.56%) deal with adult obesity only. Of the 24 SIO and/or EASO centers caring for pediatric obesity, 54.17% are located in northern Italy, 25% in the center, and 20.33% in southern and insular Italy. According to data made available by SIO records, approximately 18,000 new patients are visited on a yearly basis in northern Italy, whereas numbers are lower in central and southern/insular Italy ranging around 13–14,000. Generally, each patient with obesity is followed up on average 3–4 times a year across Italy with no major geographical difference. Conversely, territorial distribution of medically oriented obesity centers is significantly variable, with 0.17 centers per 1000 km2 in the north, 0.15 in the center, and only 0.06 in the south (Table 1). Among the 8 regions with no SIO and/or EASO accredited centers, 2 are in the north (Friuli Venezia Giulia, Valle D’Aosta), 2 in the center (Marche and Umbria) and 3 in the south (Abruzzo, Molise, Basilicata) (Fig. 1a). Based on the elaborated SIO records, the centers appear fairly homogeneous in regard to the multidisciplinary approach, the presence of a bariatric surgery division and the availability of support materials and local groups providing psychotherapy and educational therapy; most are hosted in universities and almost all have a website providing all relevant information (data not shown).

SICOB classifies centers as Of Excellence, Accredited and Affiliated, depending on criteria summarized in Table 2. All deal with the surgical treatment of severe obesity, and geographical distribution is, similar to medically oriented obesity centers, very uneven. Out of a total of 72 centers, 43 are located in northern regions (59.7%), 11 in the central ones (15.27%), and 18 in the south (25%). Lombardy is the region with more SICOB centers by far (23/72, 31.9% of total) followed by Latium and Campania with 8 centers each. Specifically, northern regions feature 22 SICOB centers of excellence (> 100 procedures/year), 9 accredited centers (> 50/year), 7 affiliates centers (> 25/year). Of the 22 northern centers of excellence, 14 are located in Lombardy. Central regions feature 7 centers of excellence, 3 accredited and 3 affiliated centers. In the south, 11 centers of excellence, 6 accredited and 4 affiliated are present. The presence of SICOB surgery centers appears more branched than the medically oriented, SIO and/or EASO affiliated ones, considering that 3 regions only have none reported: Molise and Calabria (south), and Marche (center) (Fig. 1a).

Interestingly, regional obesity prevalence is inversely correlated with the number of medically oriented SIO and/or EASO affiliated centers (R = 0.25, p = 0.03) (Fig. 1b), whereas no association is observed taking SICOB centers into account (p = 0.12, data not shown).

Discussion

Tackling the obesity epidemic is far from simple. The first challenge to address is that the problem of obesity is currently often unrecognized by both patients and healthcare professionals, together with politicians that should take charge of it. No matter the fact that evidence confirms that lifestyle interventions are ineffective in achieving and maintaining weight loss (whereas they are likely good in preventing the obesity onset) [22], many still believe the opposite [23].

Late last year, the Italian parliament voted unanimously to approve a motion that recognizes obesity as a chronic disease. It is now the Government turn to implement political strategies promoting obesity prevention and treatment. The main lines of actions are summarized in the approved motion [24]:

-

1.

to implement a homogeneous national plan on obesity that identifies a common strategic design aimed at promoting interventions based on an integrated and personalized multidisciplinary approach, centered on the person with obesity and ensuring full access to all therapeutic options;

-

2.

to monitor the correct implementation of levels of care related to the treatment of obesity complications;

-

3.

to promote the education of health workers, school operators and new parents on nutrition;

-

4.

to promote research on obesity;

-

5.

to regulate the advertising of food and drinks for children and stimulate the food industry to study an adequate portioning of products for children and adolescents.

However, the possible progress runs the risk of being undermined by constant cuts in the budget allocated for healthcare in Italy.

In the UK, a recent report has suggested that the approach to the management of obesity in the National Health Service is patchy, and that work is needed to develop and implement effective strategies to prevent and treat obesity at policy and provider level [25]. In Italy, the situation seems to be similar, with policies yet to be implemented, but most importantly, many practical steps to be taken to improve facilities oriented towards obesity treatment. Moreover, Italy has a decentralized organization, where regions, whose per capita GDP ranges from a mean of 35,000 €/year in northern regions to 18,000 € in the south [26] are responsible for the implementation of local policies and healthcare facilities, making both obtaining a clear overall picture of the situation and providing consistent care across the country a challenging task.

A gradient can be observed both between north and south and between eastern and western regions regarding the presence of obesity focused facilities targeting adult patients. Interestingly, the largest number of centers and visits in the north and eastern coast do not reflect the prevalence of obesity, which follows an opposite distribution. Children and adolescents face the same contradiction: as in the case of adults, pediatrics obesity is significantly more prevalent in southern regions, with a prevalence of 19.9% in the north, 21.4% in the center and 28.7% in the south, and children obesity centers following the same opposite gradient expressed above. Surgically oriented centers are more common in the north than the south, suggesting that morbid obesity can be more easily addressed in some areas compared to others. Finally, it should be noted that some regions appear to provide little to no specialized center according to available records. If, in the north, this might attributable to simple lack of need and sufficient presence in nearby and easily accessible locations (Valle D’Aosta, for example, reports only one SICOB accredited obesity clinic, and has one of the lowest obesity rates across Italy), in the south it could actually be due to the absence of regional implementation, if we consider that Basilicata features the country’s second highest obesity rates and yet no specialized center is available, with Molise being the most obese region, and yet only one SICOB center is available on the territory. Moreover, residential approaches represent an essential step in some cases [16], but facilities providing these services are too few and again only located in the north of Italy, limiting the access to many patients, especially from the south.

This study has several limitations, the most important being the absence of national, thorough records regarding obesity care facilities across the country to extrapolate data from. Much of presented data derives in fact from subjective evaluations provided by the obesity centers chiefs in the form of a filled questionnaire, and both over- and underestimation could have happened, together with misinterpretation of the questionnaire provided. Moreover, no record of centers not affiliated to scientific societies was retrieved, and the current picture is, therefore, potentially incomplete. Furthermore, almost half of SIO/EASO centers were also SICOB affiliated, leading to an overestimation of the total number of centers specialized in obesity care. However, it was chosen to keep the analysis of medical and surgical centers distinct, therefore, treating the single, double affiliated, center as two separate entities to facilitate the reading of the present revision. Finally, data relative to the way primary care facilities cope with obesity treatment could not be retrieved, limiting the overall picture to specialized centers.

However, to the best of our knowledge, this report is the first of its kind relative to our country, and it provides a sketch of the current situation, suggesting that the model is applied unevenly and could be unable to systematically deal with a health emergency involving such a large percentage of the population. First of all, a systematic record of the different levels of assistance and of how obesity treatment is managed across the country would be highly desirable to provide relevant data aiding the improvement. Second, greater collaboration and dialogue between specialized centers and territorial medicine, possibly through webinars and conferences targeting GPs and PEDs, would direct prevention strategies and primary care diagnosis and treatment in the most appropriate way, with the effect of relieving the current burden on second- and third-level facilities. Third, specialized centers are currently distributed throughout the country in an uneven manner, inconsistent with the areas with the highest prevalence of obesity both in adulthood and in children. National guidelines providing a minimum number of obesity centers in each region, together with making specific funding available would help levelling the situation. Fourth, obesity is currently not among the conditions classifying for prescription charge exemption in Italy. As weight excess directly relates with lower income, this further prevents the access to treatments. Making care, including pharmacologic treatment, free of charge, would be an investment worth the value. Finally, there is a major lack in the availability of residential facilities capable of accommodating patients suffering from severe obesity for the time necessary to treatment. Nursing homes usually feature facilities and professionals similar to what is desirable in residential facilities for the treatment of obesity. Repurposing a fraction of these could represent a cost-effective way to broaden the availability of such service throughout the country.

The recent parliamentary motion approval recognizing obesity as a chronic disease is indeed a step towards improvement, but only time will reveal whether these policies will be put into action leading to better prevention and care.

What is already known on this subject?

Almost no real-life data exists to delineate the actual status of the management of obesity in Italy.

What your study adds?

We provide a picture of the real-life organization in obesity care across Italian regions and conclude that many territorial differences are present, suggesting feasible ways to improve and standardize care. Other countries with similar healthcare organization might benefit from this report as issues in the real-life management of obesity are common in many ways.

Availability of data and material

All data other than SIO records is publicly available. SIO records will be made available upon reasonable request.

References

Noncommunicable Diseases Progress Monitor (2017) World Health Organization, Geneva

Prospective Studies C, Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Collins R, Peto R (2009) Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet 373(9669):1083–1096. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60318-4

Lauro R, Sbraccia P, Lenzi A (2019) 1st Italian Obesity Barometer Report. Obesity Monitor, vol 1. IBDO Foundation, Rome

Italian National Institute of Health. OKkio alla Salute: i dati nazionali 2016. (National data 2016). (2017). http://www.epicentro.iss.it/okkioallasalute/dati2016. Accessed 2020

World Health Organization, Mean body mass index trends among adults, crude (kg/m2). Estimates by country. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.BMIMEANADULT. Accessed 2020

OECD (2019) The Heavy Burden of Obesity. doi: https://doi.org/10.1787/67450d67-en

McAllister EJ, Dhurandhar NV, Keith SW, Aronne LJ, Barger J, Baskin M, Benca RM, Biggio J, Boggiano MM, Eisenmann JC, Elobeid M, Fontaine KR, Gluckman P, Hanlon EC, Katzmarzyk P, Pietrobelli A, Redden DT, Ruden DM, Wang C, Waterland RA, Wright SM, Allison DB (2009) Ten putative contributors to the obesity epidemic. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 49(10):868–913. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408390903372599

Watanabe M, Masieri S, Costantini D, Tozzi R, De Giorgi F, Gangitano E, Tuccinardi D, Poggiogalle E, Mariani S, Basciani S, Petrangeli E, Gnessi L, Lubrano C (2018) Overweight and obese patients with nickel allergy have a worse metabolic profile compared to weight matched non-allergic individuals. PLoS One 13(8):e0202683. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202683

Bluher M (2019) Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol 15(5):288–298. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-019-0176-8

GU Serie Generale n.360 del 28-12-1978 - Suppl. Ordinario (1978)

Art.32 Costituzione italiana, Parte I, titolo II (1947)

Generale n.4 del 07-01-1994 - Suppl. Ordinario n. 3 (1994)

Dong Z, Xu L, Liu H, Lv Y, Zheng Q, Li L (2017) Comparative efficacy of five long-term weight loss drugs: quantitative information for medication guidelines. Obes Rev 18(12):1377–1385. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12606

Santini F, Busetto L, Cresci B, Sbraccia P (2016) SIO management algorithm for patients with overweight or obesity: consensus statement of the Italian Society for Obesity (SIO). Eat Weight Disord 21(2):305–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0279-3

Sbraccia P, Busetto L, Santini F, Mancuso M, Nicoziani P, Nicolucci A (2020) Misperceptions and barriers to obesity management: Italian data from the ACTION-IO study. Eat Weight Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00907-6

Mariani S, Watanabe M, Lubrano C, Basciani S, Migliaccio S, Gnessi L (2015) Interdisciplinary approach to obesity. In: Multidisciplinary approach to obesity: from assessment to treatment, pp 337–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-09045-0_28

Lenzi A, Jannini EA (2017) Endocrinologia 2.0 - Libro Bianco sullo stato dell’endocrinologia Italiana. Milan, Italy

Società Italiana dell’Obesità. https://sio-obesita.org/. Accessed 2020

Società Italiana di Chirurgia dell’Obesità e delle malattie metaboliche. https://www.sicob.org/sicob2/default.aspx. Accessed 2020

The European Association for the Study of Obesity. https://easo.org/. Accessed 2020

Tsigos C, Hainer V, Basdevant A, Finer N, Mathus-Vliegen E, Micic D, Maislos M, Roman G, Schutz Y, Toplak H, Yumuk V, Zahorska-Markiewicz B, Obesity Management Task Force of the European Association for the Study of O (2011) Criteria for EASO-collaborating centres for obesity management. Obes Facts 4(4):329–333. https://doi.org/10.1159/000331236

EASO. Obesity: perception and policy – multi-country review and survey of policymakers. London: European Association for the Study of Obesity; 2014. European Association for the Study of Obesity. Policymaker Survey 2014. http://easo.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/C3_EASO_Survey_A4_Web-FINAL.pdf. Accessed 2020

Caterson ID, Alfadda AA, Auerbach P, Coutinho W, Cuevas A, Dicker D, Hughes C, Iwabu M, Kang JH, Nawar R, Reynoso R, Rhee N, Rigas G, Salvador J, Sbraccia P, Vazquez-Velazquez V, Halford JCG (2019) Gaps to bridge: misalignment between perception, reality and actions in obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab 21(8):1914–1924. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.13752

Camera dei Deputati, Legislatura 18, Mozione n. 1/00082. https://www.camera.it/temiap/2019/11/15/OCD177-4202.pdf. Accessed 2020

Capehorn MS, Haslam DW, Welbourn R (2016) Obesity treatment in the UK health system. Curr Obes Rep 5(3):320–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-016-0221-z

Istat Conti Economici territoriali 2017. https://www.istat.it/it/files/2018/12/Report_Conti-regionali_2017.pdf. Accessed 2020

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Italian Society for Obesity (SIO) for providing records of their affiliated centers.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection Italian Society of Obesity (SIO) Reviews.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Watanabe, M., Risi, R., De Giorgi, F. et al. Obesity treatment within the Italian national healthcare system tertiary care centers: what can we learn?. Eat Weight Disord 26, 771–778 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00936-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00936-1