Abstract

Purpose

The present study evaluated the statistical and clinical significance of symptomatic change at discharge and after 6 months of an intensive residential treatment for patients with eating disorders (ED), and explored the individual factors that may affect therapeutic outcomes.

Methods

A sample of 118 female ED patients were assessed at intake and discharge on the following dimensions: BMI, ED-specific symptoms, depressive features, and overall symptomatic distress. A subsample of 59 patients filled out the same questionnaires at a 6-month follow-up after discharge.

Results

Findings evidenced statistically significant changes in all outcome measures at both discharge and follow-up. Between 30.1 and 38.6% of patients at discharge and 35.2–54.2% at the 6-month follow-up showed clinically significant symptomatic change; additionally, 19.8–29.1% of patients at discharge and 22.9–38.3% at follow-up improved reliably. However, 34.9–39.8% remained unchanged and 2–4.8% worsened. At the 6-month follow-up, 21.3–25.9% showed no symptomatic change and 0–3.7% had deteriorated. Unchanged and deteriorated patients had an earlier age of ED onset and were more likely to suffer a comorbid personality pathology and to be following concurrent pharmacological treatment.

Conclusions

Results suggested that intensive and multimodal residential treatment may be effective for the majority of ED patients, and that therapeutic outcomes tend to improve over time. Prevention strategies should focus on early onset subjects and those with concurrent personality pathology.

Level of evidence

Level III, evidence obtained from a longitudinal cohort study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Eating disorders (ED) are commonly considered amongst the most challenging psychiatric disorders to treat, showing high rates of psychiatric and medical comorbidity [1,2,3], elevated mortality rates [4, 5], and significant recidivism [6]. Furthermore, several studies have shown that ED patients typically develop a history of negative therapy experiences and repeated treatment failure [7, 8], ranging from dropout [9, 10] to relapse [11].

To overcome these clinical challenges, most guidelines agree that there should be a continuum of care linked to the patient’s symptom severity, overall medical status, treatment history, and social circumstances [12, 13]. Among the ED treatment services available, intensive residential treatment settings are recommended for patients who are medically stable and not actively suicidal, but who show severe and persistent ED symptoms associated with poor-to-fair motivation to change and psychiatric comorbidities. Residential care settings offer a structured treatment program similar to inpatient hospital settings, but in a more homelike environment. Patients typically receive both individual and group therapies, multidisciplinary interventions, meal support, and nutritional counseling [14]. These therapeutic programs are considered a viable and comfortable alternative to traditional inpatient psychiatric centers for ED patients who fail to respond to outpatient or partial hospital programs. However, a recent review showed that empirical evidence on their effectiveness is scarce, and few studies have reported follow-up data [15].

The limited data available suggest that the majority of ED patients show significant improvement in eating behaviors, ED-specific symptoms, and depressive and global psychopathology at discharge [16,17,18], as well as a significantly higher BMI in low-weight patients and reduced binge frequency in bulimia nervosa (BN) patients [17]. Preliminary follow-up data suggest that these improvements are generally maintained over time [19, 20], but the large variability in follow-up periods and high rates of dropout or missing data render these findings inconclusive [15].

Another limitation of the aforementioned studies is that the effectiveness of residential treatment has been investigated only through traditional significance testing at the group level, despite the increasing need to report outcome findings in other clinically meaningful ways [21]. For instance, Jacobson and Truax’s [22] clinical significance (CS) method is a statistical approach that uses data from well-established self-report measures to systematically classify treatment response at the individual level (i.e., clinically improved/recovered, reliably improved but not recovered, unchanged, or deteriorated). This approach has been previously used to compare outcomes of individual and group outpatient treatment for bulimic [23] and mixed ED [24] patients, to evaluate the effectiveness of day treatment programs for ED patients [25], and to examine the effects of a prevention program designed to reduce ED risk factors in children [26].

Three studies explored the CS of symptomatic change after intensive inpatient treatment for ED. Schlegl and colleagues [27] found that 20–32% of patients with anorexia nervosa (AN) showed reliable change and 34.1–55.3% showed clinically significant change in various outcome measures at discharge, whereas 23–34.5% remained unchanged and 1.7–3% deteriorated. In a subsequent study on adolescents, approximately 23.6% of patients showed reliable change and 44.7% showed clinically significant change with regard to ED symptomatology, while 28% remained unchanged and 3.7% worsened [28]. In both studies, patients who showed clinically significant change had lower overall and ED-specific symptoms at admission and were less likely to have comorbid depression. Furthermore, Diedrich and colleagues [29] found that 33.9–56.9% of bulimic patients showed clinically significant change and 18.1–34.8% showed reliable change, whereas 21.1–26.9% experienced no symptomatic improvement and 2–4.4% worsened. Patients with clinically significant improvement were less distressed at intake and less likely to suffer from a comorbid borderline personality disorder.

Despite these promising results, to date, no studies have applied the CS approach to residential care settings. Moreover, a growing body of evidence suggests that ED remission is best estimated over time [15]. Thus, the present study aimed at extending previous findings by evaluating the effectiveness of an intensive residential treatment for ED patients in terms of the statistical and clinical significance of symptom change. It further aimed at offering preliminary findings on therapeutic change at a 6-month follow-up to explore the mid-term stability of treatment outcomes assessed with the CS method. Finally, it also examined the individual variables that might affect ED patients’ responses to residential treatment programs.

In line with previous studies, it was expected that ED residential treatment would be statistically significantly effective at the group level at both discharge and the 6-month follow-up. Furthermore, it was hypothesized that clinically significantly changed patients would show less symptomatic impairment at intake, as well as lower comorbidity with depressive or personality disorders.

Methods

Participants and procedure

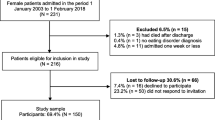

Participants were patients who had been consecutively admitted to a specialized and multimodal residential treatment center for ED in Bologna (Italy) between May 2016 and June 2018. The inclusion criteria were: (a) at least 18 years of age; (b) a diagnosis of DSM-5 AN or BN, established at intake by the consensus of a licensed staff psychiatrist and a clinical psychologist, based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5-CV) [30]; (c) female gender; and (d) no organic syndrome, psychotic disorder, or syndrome with psychotic symptoms.

An initial sample of N = 156 met these criteria. Twenty-three (14.7%) were excluded due to premature discharge or dropout and 15 (11.2%) were not considered due to missing data at intake and/or discharge. Prematurely discharged patients were excluded from the analyses due to the short duration of their stay in treatment (M = 1.35 months, SD = 1.30, range = 0.03–4.68), which led to missing data. Patients were reported to have prematurely left the residential program due to scarce personal motivation or compliance (N = 12, 52.2%), transfer to a psychiatric unit (N = 5, 21.7%) or hospital setting (N = 4, 17.4%), or a high risk of suicide (N = 2, 8.7%). They did not differ from regularly discharged patients in terms of age (F[1, 139] = 0.03, p = .85), ED diagnosis (χ2[2, N = 141] = 3.09, p = .21), pharmacotherapy (χ2[2, N = 141] = .01, p = .92), or BMI (F[1, 139] = 1.19, p = .27]) at intake; however, they did show a significant difference with respect to their shorter treatment length (F[1, 139] = 59.83, p ≤ .001).

Out of the final study sample of N = 118 patients who completed all assessment measures at treatment intake and discharge, 58 (49.1%) were diagnosed with Anorexia Nervosa Restricting type (AN-R) with an average baseline BMI of 15.44 kg/m2, while 26 (22%) fulfilled diagnostic criteria for Anorexia Nervosa Purging type (AN-P) with an average BMI of 16.51 kg/m2; the remaining 34 patients (28.8%) were diagnosed with Bulimia Nervosa (BN) and showed a baseline BMI of 23.04 kg/m2. Thirty-one patients (26.3%) declined to participate in the 6-month follow-up assessment due to personal or unspecified reasons, 16 (13.5%) relapsed and were admitted to inpatient treatment for an ED, 11 (9.3%) were hospitalized due to medical complications, and 1 (0.8%) was untraceable. Thus, more than half of the sample (response rate = 56.7%, N = 59) filled out self-report questionnaires at the 6-month follow-up. As shown in Table 1, patients who did not provide follow-up data showed higher levels of overall symptomatic distress at intake.

During the first and the last week of treatment, all patients were administered the SCID-5-CV and a set of self-report measures to assess ED symptoms, overall psychopathology, and depression. Additionally, height and weight were measured during a full medical examination to calculate BMI. The 6-month follow-up assessments were conducted exclusively in person after an appointment was scheduled by phone, and patients were asked to complete all self-rating measures following an unstructured clinical interview with the primary staff psychiatrist and clinical psychologist. Thus, the 6-month follow-up did not include a medical screening and BMI calculation. The follow-up timing of 6 months was chosen as the most appropriate to reflect the effectiveness of the residential treatment program and to detect the mid-term maintenance of treatment gains; at the same time, it aimed at minimizing the potential confounding effect of further treatment and other maturational processes on the level of patient improvement. Study subjects participated voluntarily and provided written informed consent prior to the assessments, following a review and approval of the study protocol by the local research ethics committee. Table 1 presents all descriptive information of the study sample.

Residential treatment program

Once patients were admitted, they received an intense, multimodal residential treatment program based on an integrated theoretical approach with a main psychodynamic approach and cognitive-behavioral interventions applied to eating pathologies [31, 32], including both group and individual psychotherapy. Average treatment length was 5.38 months (SD = 2.37, range = 3–13).

According to the most widespread practice guidelines for ED treatment, a team approach and a patient-tailored perspective were the cornerstones of the therapeutic program [14]. Thus, a multidisciplinary team of specialized professionals (i.e., psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, nutritionists, physicians, and nurses) met on a weekly basis to discuss cases within a psychodynamic theoretical framework. Each patient received individual psychotherapy once or twice a week on the basis of a comprehensive examination of his or her psychological development, psychodynamic issues, cognitive style, comorbid psychopathology, and family situation. All clinical psychologists reported psychodynamic therapy as their primary orientation, with a more eclectic stance toward ED patients showing greater comorbidity. Thus, the contents of the individual psychotherapy included interventions that focused on patients’ conflicting feelings or desires, linked their current feelings and perceptions to past experiences to identify recurrent patterns, addressed patients’ use of symptoms to avoid emotions, and used the therapeutic relationship as both a source of information about patients’ interpersonal functioning and a vehicle through which to offer them a new model for relationships. To provide a therapeutic approach that was tailored to each patient, therapists might also use cognitive-behavioral interventions such as psycho-education on current ED symptoms, the physical short- and long-term consequences of eating disorders, and treatment goals.

Group treatment was provided three times per week and included psycho-education, interventions focused on affective and emotional experiences, recreational and art therapy, social cooking, and social skills training.

Nutritional rehabilitation was provided through an individualized meal plan and nutritional counseling by specialized dietitians to restore healthy body weight, normalize eating patterns, and achieve normal perceptions of hunger and satiety. Furthermore, a weekly full medical assessment was performed by a registered physician specialized in treating ED patients. Patient care also included the provision of educational materials, such as information on community-based and Internet resources, and advice for families, where appropriate. A detailed description of patients’ daily activities is provided in Table 2.

Measures

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5, Clinical Version (SCID-5-CV) [30] The SCID-5-CV is a semi-structured interview designed to categorically assess psychopathology according to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manuals of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). It is typically administered by a clinician who is familiar with the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. Interview questions are provided alongside each DSM-5 criterion to aid users in rating each criterion as either present or absent. The previous version of the interview (SCID-IV) showed good interrater and test–retest reliability [33].

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Personality Disorders (SCID-5-PD) [34] The SCID-5-PD is a 119-item semi-structured interview used to evaluate the 10 DSM-5 personality disorders in Clusters A, B, and C. It can be used to diagnose personality disorders categorically (present or absent) or dimensionally. In the present study, only the categorical classification was available. The previous version, the SCID-II, demonstrated good psychometric properties [33].

Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3) [35] The EDI-3 is a self-report questionnaire that is widely used in both research and clinical settings to assess the core components of eating psychopathology. It consists of 91 items organized into 12 primary scales, consisting of three ED-specific scales and nine general psychological scales that are highly relevant to EDs. It also yields six composite scores: one that is ED-specific and five that are general integrative psychological constructs. The EDI-3 yields adequate convergent and discriminant validity [36]. In the present study, Cronbach’s alphas for the EDI-3 scores ranged from 0.70 to 0.94.

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) [37] The BDI-II is a 21-item self-rating inventory that evaluates the presence and severity of depressive symptomatology. Each item is rated on a scale of 0–3 in terms of occurrence and intensity over the past 7 days, with summary scores ranging between 0 and 63. Several studies have demonstrated that the BDI-II has adequate internal consistency, test–retest reliability, construct validity, and factorial validity [38]. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the BDI-II score was 0.86.

Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) [39] The SCL-90-R is a widely used self-report instrument assessing 90 psychiatric symptoms on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 to 4, indicating the extent to which the patient suffered from each symptom over the past 7 days. The Global Severity Index (GSI) summarizes the patient’s overall psychopathological symptom severity and is commonly used as a measure of therapeutic change. Its reliability and validity have been demonstrated in numerous studies (e.g., [40]). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the SCL-90 GSI score was 0.97.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 25 for Windows. To evaluate the statistical significance of BMI and symptomatic change, separate repeated measure ANOVAs were applied to each outcome measure using the within-subject factor of “time” (pre- and post-intervention) and a covariate of treatment duration [27, 41]. Furthermore, partial eta squares for pre–post effect sizes were calculated to quantify treatment effects. According to Cohen’s [42] guidelines, partial η2 ≥ 0.01 corresponded to a small effect, partial η2 ≥ 0.06 was regarded as a medium effect, and partial η2 ≥ 0.14 was considered a large effect.

The clinical significance of symptom change was determined according to the criteria proposed by Jacobson and Truax [22] and followed the recommendations of Bauer and colleagues [43]. The first step was to determine whether a patient’s change was reliable or the result of measurement error or chance. Thus, a reliable change index (RCI) was calculated by subtracting the post-treatment score from the pre-treatment score and dividing the resulting figure by the standard error of difference (Sdiff) between the test scores. Jacobson and Truax’s formula is: RCI = Xpre − Xpost/Sdiff, with Sdiff = \(\sqrt {2\left( {\text{SE}} \right)}\)2 and SE = s1 \(\sqrt {(1 - r_{xx} }\)), where Xpre is the patient’s score at intake, Xpost is the patient’s post-treatment score at discharge, SE is the standard error of measurement, s1 is the standard deviation of the patient group at intake, and rxx is the reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) of the corresponding measure. Internal consistency estimates were preferred to test–retest coefficients [44, 45]. Using a confidence level of 95%, RCI ≥ 1.96 was considered a reliable positive change.

The second step was to calculate a cut-off point to assess whether a patient outcome score fell within the functional or dysfunctional population range (as determined by normative and clinical sample scores in each measure’s manual) [46,47,48]. The most conservative approach (“criterion c”) was employed with the following formula: C = \(\frac{{{\text{SD}}_{0} *M_{1} + {\text{SD}}_{1} *M_{0} }}{{{\text{SD}}_{0} + {\text{SD}}_{1} }}\). M0 and SD0 represented the mean and standard deviation of the normative sample, respectively, while M1 and SD1 represented the corresponding indices of the dysfunctional/clinical population.

These two calculations were then combined to classify the sample into five outcome groups: (a) a normative group of patients with scores within the functional range at both pre- and post-treatment; (b) patients showing clinically significant improvement who met both criteria (i.e., reliable pre–post change and post-treatment scores in the functional range); (c) patients showing reliable improvement after treatment but remaining in the dysfunctional range; (d) patients showing no change, who demonstrated no reliable change and remained in the dysfunctional range; and (e) patients showing reliable deterioration, who worsened reliably (i.e., RCI ≤ − 1.96). In line with previous investigations, in the present study we did not include patients with normative scores at intake and discharge. We considered three outcome indices: the GSI of the SCL-90-R, the BDI-II, and the EDI-3 Eating Disorder Risk (EDRC) composite score. We chose the EDRC because it is ED-specific and not related to other general integrative psychological constructs.

Finally, to explore the impact on sociodemographic, clinical, and treatment-specific variables on patients’ responses to treatment, we computed separate univariate ANOVAs for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables to test the differences between outcome groups.

Results

Pre–post change

BMI In patients diagnosed with AN-R, average BMI rose from 15.44 kg/m2 (SD = 3.19) to 17.98 kg/m2 (SD = 2.72) (ES = .07, p = .05) during residential treatment. Treatment length significantly contributed to this pre − post change (ES = .08, p = .03). Similarly, patients with AN-P showed a significant increase in average BMI, from 16.51 kg/m2 (SD = 2.43) to 18.08 kg/m2 (SD = 2.28) (ES = .16, p = .04). Patients diagnosed with BN did not show a significant difference in average BMI from intake (M = 23.04, SD = 6.26) to discharge (M = 22.44, SD = 4.48) (ES = .003, p = .74). Treatment duration did not affect BMI change in patients with AN-R and BN (both ES < .01).

ED symptomatology As shown in Table 3, most of the EDI-3 subscales and composite scores showed statistically significant change at discharge, except for Interpersonal Alienation, Emotional Dysregulation, and Ascetism. The highest effect sizes were found for the Eating Disorder Risk and Global Psychological Maladjustment composite scores, as well as for Drive for Thinness, Low Self-Esteem, and Interoceptive Deficits. Treatment length showed a significant effect only on the pre–post change in Interpersonal Alienation. Considering the clinical significance, we found that 30.1% of patients fulfilled the criteria for clinically significant improvement, and an additional 26.2% showed reliable symptomatic change, even though they remained within the dysfunctional population. Conversely, 39.8% showed no improvement and 3.9% worsened (see Fig. 1).

Psychopathological symptoms Similarly, symptomatic change measured by the GSI of the SCL-90 was statistically significant, with a moderate effect size (ES = 0.10). On this measure, treatment length had no significant effect. In total, 31.1% of patients showed clinically significant symptom change and 29.1% showed reliable improvement, while 34.9% experienced no symptomatic change and 4.8% deteriorated (see Fig. 1).

Depression As shown in Table 3, results showed statistically significant improvement in depressive symptoms with a large effect size (ES = 0.14). Treatment duration did not have a significant effect on pre–post change. Furthermore, 38.6% of patients demonstrated clinically significant improvement and 19.8% showed reliable change, whereas 39.6% remain unchanged and 2.0% worsened (see Fig. 1).

Change at 6-month follow-up

ED symptomatology Table 4 presents the statistical significance of symptomatic change at the 6-month follow-up. All of the EDI-3 subscales and composite scores showed statistically significant change at the 6-month follow-up, except for Emotional Dysregulation and Interpersonal Problems. Treatment duration did not affect symptomatic change in any of the EDI-3 subscales. In line with the pre–post change evaluation, the Global Psychological Maladjustment composite score showed the highest effect size, followed by Low Self-Esteem, Interoceptive Deficits, Eating Disorder Risk, and Drive for Thinness. As Fig. 2 shows, 35.2% of patients showed clinically significant improvement and 35.2% showed reliable change. On the other hand, 25.9% of patients experienced no symptom amelioration and 3.7% deteriorated.

Psychopathological symptoms Therapeutic change in overall psychopathology at the 6-month follow-up was statistically significant, with a moderate effect size (ES = 0.12). Similar to ED symptomatology, treatment length did not show any significant effect. Moreover, 38.3% of patients improved in a clinically significant way and 38.3% improved reliably, whereas 21.3% remained unchanged and 2.1% worsened (see Fig. 2).

Depression Change in depressive symptoms at the 6-month follow-up was statistically significant, with a large effect size (ES = 0.18). Treatment duration did not affect therapeutic change. Furthermore, 54.2% of patients showed clinically significant change, 22.9% demonstrated reliable improvement, 22.9% showed no change, and none deteriorated.

Differences between outcome groups

Due to the small percentage of deteriorated patients, they were included in the “unchanged” group in tests of differences between outcome groups at discharge. As shown in Table 5, there were significant overall differences between the three outcome groups in terms of ED-specific symptoms at intake and several baseline variables, including number of dietary restrictions per week, concurrent psychotropic medication, and comorbid personality disorders. Specifically, post hoc analyses showed that deteriorated/unchanged patients had an earlier age of ED onset and were more likely to suffer a comorbid personality pathology, especially borderline or obsessive–compulsive personality disorders. Furthermore, they were more likely to be undergoing concurrent pharmacological treatment. Surprisingly, only the EDI-3 EDRC scale significantly differentiated the three outcome groups, with reliably improved patients demonstrating higher levels of ED symptomatology at intake compared to clinically significantly improved and deteriorated/unchanged patients.

Discussion

The findings indicate that intensive and multimodal residential treatment may be an effective therapeutic option for patients with severe EDs, as such patients showed clinically and statistically significant improvements from admission to discharge, as well as at a 6-month follow-up. The statistical results are consistent with previous findings reporting significant improvement in several outcome measures at discharge and follow-up after residential treatment care for this clinical population [15, 16, 19, 49]; they are also comparable with the findings of recent studies on inpatient program facilities [18, 27,28,29, 41, 50, 51] and day treatment programs [25] for ED patients. Small-to-medium effect sizes at discharge and medium to large effect sizes at the 6-month follow-up were found, especially with respect to depressive and ED-specific symptoms. This suggests that the therapeutic changes were generally stable or even improved at the 6-month follow-up. This finding supports Lowe and colleagues’ [19] study, which found improvements in depression and ED symptomatology following residential treatment to remain evident at a 3-month follow-up. Contrary to expectations, treatment duration did not affect symptomatic change at the group level, except with respect to BMI change at discharge in AN-R patients. This finding is in line with previous research showing that the length of stay in residential or inpatient treatment programs (which is generally shorter than outpatient therapy) is significantly correlated with BMI change, but does not predict improvements in ED-related and overall psychopathological symptoms [27, 52].

The results on clinical significance showed that—depending on the outcome measure—30–39% of patients at discharge and 35–54% at follow-up experienced clinically significant symptomatic improvement, even shifting into the functional population range. A further 20–29% of patients at discharge and 23–38% at follow-up responded reliably in terms of lower overall ED pathology and fewer general and depressive symptoms. However, a significant percentage of patients (35–40%) at discharge remained unchanged, but this percentage decreased in the follow-up period ( 21–26%). Of note, few patients showed reliable deterioration at discharge (2–5%) and follow-up (0–4%). In comparison with previous studies that applied the CS method to evaluate outcomes of inpatient treatment for ED patients, the rates of reliable change found in the present study were slightly lower [27,28,29]. A possible explanation for this is the prevalence of AN patients in our sample (especially those of the “restricting” subtype), who typically show a worse treatment outcome and prognosis than BN patients (e.g., [53]). Furthermore, the rates of unchanged patients found in the present study are in line with those identified in the large body of clinical and empirical literature suggesting that a moderate percentage of ED patients develop a chronic, severe, and enduring eating pathology [54] that is likely to be unresponsive to a relatively short-term treatment approach. On the other hand, the deterioration rates are roughly comparable to those found in similar studies on ED patients [27,28,29] and significantly lower than those found in psychotherapy research, in general. In reviewing the empirical literature on negative therapeutic effects, Lambert [55] outlined that approximately 5–10% of adult patients worsen after treatment and that, at best, fewer than 50% of ED patients achieve reasonable remission.

When comparing the three outcome groups, contrary to our expectations, lower depressive and overall symptomatic impairment at intake did not characterize improved patients, whereas higher levels of ED-specific symptomatology differentiated patients who improved reliably. While this may seem counterintuitive, the more severe ED symptoms at the beginning of treatment may explain why these patients remained in the dysfunctional range of functioning, even when they demonstrated symptomatic improvement. A similar finding emerged in Schlegl and colleagues’ [27] study, in which reliably improved patients showed higher levels of depressive symptoms compared to other outcome groups.

On the other hand, in the present study, several baseline variables shed light on the clinical characteristics of the deteriorated/unchanged patients. First, these patients had a significantly earlier age of ED pathology onset, which has previously emerged as a predictor of more severe symptomatic impairment in AN patients [56] and has been linked to a longer duration of illness [57]. Second, they were more likely to suffer from a comorbid personality pathology. Personality disorders are commonly found to occur among ED patients [3, 58, 59], and a comorbid personality disorder has been shown to increase the risk of premature treatment termination and negative therapeutic outcomes [10]. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that ED patients with co-occurring BPD symptoms tend to have more severe problems on multiple indices of psychosocial functioning [60]. Third, they are more likely to assume psychotropic medication prior to treatment, suggesting higher levels of symptomatic impairment. Finally, the three outcome groups differed in terms of their number of dietary restrictions per week, despite the post hoc analyses yielding non-significant results. Prospective studies have shown that restrictive dieting predicts both the onset and worsening of EDs [61], particularly in AN patients [62].

There were several limitations of this study. First, there was a substantial loss of respondents at the 6-month follow-up, with a response rate of only 56.7%. Although there were few differences between those who did and did not provide data at follow-up, future studies should increase participation rates in follow-up evaluations, also considering longer time points (e.g., 1–2 years post-treatment). Patients with no follow-up data showed higher levels of psychopathological symptoms as measured by the SCL-90-R; thus, the present study may not adequately capture the course of patients who tended to achieve poorer outcomes and the results may be inflated in the direction of positive outcomes [15]. It is relevant to note that such limitations have been common in the few follow-up studies on the effectiveness of residential or inpatient treatment settings [18, 19, 49]. Another important limitation is that the study sample was mixed in terms of ED diagnoses, and the majority of patients were diagnosed with AN (purging or restricting types). Although the findings were comparable to those of similar studies of AN and BN patients [27,28,29], further replication considering AN or BN patient groups, specifically, is needed. Future studies should also explore which variables affect treatment dropout or premature discharge in residential treatments for ED patients. Furthermore, all measures considered in the CS approach were self-report, data were collected from a single residential treatment center, information about ED behaviors at discharge and BMI at the 6-month follow-up were not available, and the multidisciplinary nature of the therapeutic approach did not facilitate a deep understanding of the kind of intervention that would be most effective at promoting clinically significant or reliable change.

Furthermore, the CS method and its formulas, as proposed by Jacobson and Truax, also suffer from some limitations. Criticism of the RCI has focused on the phenomenon of regression toward the mean [63] and the dependence of the criterion c from the outcome measure considered. However, several studies comparing different methodologies to assess clinical significance have shown high rates of agreement between them [64, 65], suggesting that such methods are substantially equivalent and reliable.

The present study suggested that the CS approach can facilitate a deeper understanding of the variability of ED patients’ responses to treatment and can generate results that are able to be communicated in everyday language and used to guide the treatment of individual patients [24]. Specifically, it might be particularly useful to provide clinicians with findings on variables that may interfere with patients’ remission process to inform future practice in the area of residential treatment.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Birmingham LC (2015) Medical complications and diagnosing eating disorders. In: Smolak L, Levine MP (eds) The Wiley handbook of eating disorders. Wiley, UK, pp 170–182

Blinder BJ, Cumella EJ, Sanathara VA (2006) Psychiatric comorbidities of female patients with eating disorders. Psychosom Med 68:454–4623. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000221254.77675.f5

Martinussen M, Friborg O, Schmierer P et al (2017) The comorbidity of personality disorders in eating disorders: a meta-analysis. Eat Weight Disor 22(2):201–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0345-x

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Smink FR, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW (2012) Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Curr Psychiatry Rep 14(4):406–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y

Wonderlich S, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD et al (2012) Minimizing and treating chronicity in the eating disorders: a clinical overview. Int J Eat Disorder 45(4):467–475. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20978

Steinhausen H-C (2009) Outcome of eating disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Cl 18(1):225–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2008.07.013

Woodside DB, Carter JC, Blackmore E (2004) Predictors of premature termination of inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 161(12):2277–2281. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2277

Fassino S, Pierò A, Tomba E, Abbate-Daga G (2009) Factors associated with dropout from treatment for eating disorders: a comprehensive literature review. BMC Psychiatry 9:67–75. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-9-67

Pham-Scottez A, Huas C, Perez-Diaz F et al (2012) Why do people with eating disorders drop out from inpatient treatment? The role of personality factors. J Nerv Ment Dis 200(9):807–813. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e318266bbba

Grilo CM, Pagano ME, Stout RL et al (2012) Stressful life events predict eating disorder relapse following remission: six-year prospective outcomes. Int J Eat Disord 45(2):185–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20909

American Psychiatric Association (2006) Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders, 3rd edn. American Psychiatric Publishing, VA

NICE (2004) National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health: eating disorders: core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and related eating disorders. British Psychological Society, Royal college of Psychiatrists, London

Weltzin TE, Fitzpatrick ME (2015) The eating disorders treatment team and continuum of care: saving lives and optimizing treatment. In: Smolak L, Levine MP (eds) The Wiley handbook of eating disorders. Wiley, UK, pp 685–697

Friedman K, Ramirez AL, Murray SB et al (2016) A narrative review of outcome studies for residential and partial hospital-based treatment of eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev 24(4):263–276. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2449

Brewerton T, Costin C (2011) Long-term outcome of residential treatment for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Eat Disord 19:132–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2011.551632

Hoffart A, Lysebo H, Sommerfeldt B, Rø O (2010) Change process in residential cognitive therapy for bulimia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev 18:367–375. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.980

Thompson-Brenner H, Boswell JF, Espel-Huynh H, Brooks G, Lowe MR (2018) Implementation of transdiagnostic treatment for emotional disorders in residential eating disorder programs: a preliminary pre-post evaluation. Psychother Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2018.1446563

Lowe M, Davis W, Annuziato R, Lucks D (2003) Inpatient treatment for eating disorders: outcome at discharge and 3-month follow-up. Eat Behav 4(385–397):15000964

Weltzin T, Kay B, Cornella-Carlson T, Timmel P et al (2014) Long-term effects of a multidisciplinary residential treatment model on improvements of symptoms and weight in adolescents with eating disorders. J Group Add Rec 9:71–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/1556035X.2014.868765

Wise EA (2004) Methods for analyzing psychotherapy outcomes: a review of clinical significance, reliable change, and recommendations for future directions. J Pers Assess 82(1):50–59. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8201_10

Jacobson NS, Truax P (1991) Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psych 59(1):12–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12

Lundgren JD, Danoff-Burg S, Anderson DA (2004) Cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa: an empirical analysis of clinical significance. Int J Eat Disord 35(3):262–274. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10254

Clinton D, Birgegård A (2017) Classifying empirically valid and clinically meaningful change in eating disorders using the eating disorders inventory, version 2 (EDI-2). Eat Behav 26:99–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.02.001

Ben-Porath DD, Wisniewski L, Warren M (2010) Outcomes of a day treatment program for eating disorders using clinical and statistical significance. J Contemp Psychother 40(2):115–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-009-9125-5

Ponce Escoto, de León MC, Mancilla Díaz JM, Camacho Ruiz EJ (2008) A pilot study of the clinical and statistical significance of a program to reduce eating disorder risk factors in children. Eat Weight Disord 13(3):111–118

Schlegl S, Quadflieg N, Löwe B, Cuntz U, Voderholzer U (2014) Specialized inpatient treatment of adult anorexia nervosa: effectiveness and clinical significance of changes. BMC Psychiatry 14:258. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0258-z

Schlegl S, Diedrich A, Neumayr C, Fumi M, Naab S, Voderholzer U (2016) Inpatient treatment for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: clinical significance and predictors of treatment outcome. Eur Eat Disord Rev 24(3):214–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2416

Diedrich A, Schlegl S, Greetfeld M, Fumi M, Voderholzer U (2018) Intensive inpatient treatment for bulimia nervosa: statistical and clinical significance of symptom changes. Psychother Res 28(2):297–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2016.1210834

First MB, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS et al (2013) Structured clinical interview for DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association, VA

Abbate-Daga G, Marzola E, Amianto F, Fassino S (2016) A comprehensive review of psychodynamic treatments for eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord 21(4):553–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0265-9

Murphy R, Straebler S, Cooper Z, Fairburn CG (2010) Cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders. Psychiatry Clin N Am 33(3):611–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.004

Lobbestael J, Leurgans M, Arntz A (2011) Inter-rater reliability of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders (SCID I) and axis II disorders (SCID II). Clin Psychol Psychother 18(1):75–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.693

First MB, Williams JBW, Benjamin L et al (2016) Structured clinical interview for DSM-5 personality disorders (SCID-5-PD). American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington, DC

Garner DM (2004) Eating disorder inventory-3: professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Lutz, FL

Clausen L, Rosenvinge JH, Friborg O, Rokkedal K (2011) Validating the eating disorder inventory-3 (EDI-3): a comparison between 561 female eating disorders patients and 878 females from the general population. J Psychopathol Behav 33(1):101–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-010-9207-4

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK (1996) Manual for the beck depression inventory-II. Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX

Wang Y-P, Gorenstein C (2013) Psychometric properties of the beck depression inventory-II: a comprehensive review. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 35(4):416–431. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048

Derogatis LR (1994) Symptom checklist-90-R: administration, scoring, and procedures manual, 3rd edn. National Computer Systems, Minneapolis, MN

Prunas A, Sarno I, Preti E, Madeddu F, Perugini M (2012) Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the SCL-90-R: a study on a large community sample. Eur Psychiatry 27(8):591–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.12.006

Naab S, Schlegl S, Korte A et al (2013) Effectiveness of a multimodal inpatient treatment for adolescents with anorexia nervosa in comparison with adults: an analysis of a specialized inpatient setting: treatment of adolescent and adult anorexics. Eat Weight Disord 18(2):167–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-013-0029-8

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ

Bauer S, Lambert MJ, Nielsen SL (2004) Clinical significance methods: a comparison of statistical techniques. J Pers Assess 82(1):60–70. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8201_11

Martinovich Z, Saunders S, Howard KI (1996) Some comments on “assessing clinical significance”. Psychother Res 6(2):124–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503309612331331648

Tingey RC, Lambert MJ, Burlingame GM, Hansen NB (1996) Clinically significant change: practical indicators for evaluating psychotherapy outcome. Psychother Res 6(2):144–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503309612331331668

Giannini M, Pannocchia L, Dalla Grave R et al (2008) Eating disorder inventory—3: Italian manual. Giunti OS, Florence

Sarno I, Preti E, Prunas A et al (2013) Symptom checklist-90-R: Italian adaptation. Giunti OS, Florence

Ghisi M, Flebus GB, Montano A et al (2006) Beck depression inventory – II: Italian manual. Giunti OS, Florence

Gleaves DH, Post GK, Eberenz KP, Davis WN (1993) A report of 497 women hospitalized for treatment of bulimia nervosa. Eat Disord 1(2):134–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640269308248281

Goddard E, Hibbs R, Raenker S et al (2013) A multi-centre cohort study of short term outcomes of hospital treatment for anorexia nervosa in the UK. BMC Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-287

Collin P, Power K, Karatzias T, Grierson D, Yellowlees A (2010) The effectiveness of, and predictors of response to, inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev 18(6):464–474. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1026

Morris J, Simpson AV, Voy SJ (2015) Length of stay of inpatients with eating disorders. Clin Psychol Psychother 22(1):45–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1865

Herzog DB, Dorer DJ, Keel PK et al (1999) Recovery and relapse in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: a 75-year follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 38(7):829–837. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199907000-00012

Steinhausen H-C (2002) The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the 20th century. Am J Psychiatry 159(8):1284–1293. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1284

Lambert MJ (2013) The efficacy and the effectiveness of psychotherapy. In: Lambert MJ (ed) Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, pp 169–218

Abbate-Daga G, Pierò A, Rigardetto R, Gandione M, Gramaglia C, Fassino S (2007) Clinical, psychological and personality features related to age of onset of anorexia nervosa. Psychopathology 40(4):261–268. https://doi.org/10.1159/000101731

Reas DL, Schoemaker C, Zipfel S, Williamson DA (2001) Prognostic value of duration of illness and early intervention in bulimia nervosa: a systematic review of the outcome literature. Int J Eat Disord 30(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.1049

Lilenfeld LRR, Wonderlich S, Riso LP et al (2006) Eating disorders and personality: a methodological and empirical review. Clin Psychol Rev 26(3):299–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.10.003

Westen D, Harnden-Fischer J (2001) Personality profiles in eating disorders: rethinking the distinction between axis I and axis II. Am J Psychiatry 158(4):547–562. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.547

Wonderlich SA, Swift WJ (1990) Borderline versus other personality disorders in the eating disorders: clinical description. Int J Eat Disord 9(6):629–638. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(199011)9:6%3c629:AID-EAT2260090605%3e3.0.CO;2-N

Stice E, Burger K (2015) Dieting as a risk factor for eating disorders. In: Smolak L, Levine MP (eds) The Wiley handbook of eating disorders. Wiley, UK, pp 312–323

Lloyd EC, Øverås M, Rø Ø, Verplanken B, Haase AM (2019) Predicting the restrictive eating, exercise, and weight monitoring compulsions of anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00674-z

Hsu LM (1989) Reliable changes in psychotherapy: taking into account regression toward the mean. Behav Assess 11(4):459–467

Speer DC, Greenbaum PE (1995) Five methods for computing significant individual client change and improvement rates: support for an individual growth curve approach. J Consult Clin Psychol 63(6):1044–1048. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.63.6.1044

McGlinchey JB, Atkins DC, Jacobson NS (2002) Clinical significance methods: which one to use and how useful are they? Behav Therpy 33(4):529–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(02)80015-6

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Giovanna Cuzzani, Dr. Anna Franco, Dr. Milena Montaguti, Dr. Micaela Riboldi, and Dr. Francesca Rossi for generously contributing to this research project. The authors also want to express their gratitude to Dr. Massimo Recalcati, who discussed this work with them since the beginning, and to Andrea Florio and Silvia Maso for their help with data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee (Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Dynamic and Clinical Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome; Approval document reference number: 0000398) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Muzi, L., Tieghi, L., Rugo, M.A. et al. Evaluating empirically valid and clinically meaningful change in intensive residential treatment for severe eating disorders at discharge and at a 6-month follow-up. Eat Weight Disord 25, 1609–1620 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00798-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00798-2