Abstract

Purpose

Breast cancer is one of the most important health problems faced by women. No study was found in the world literature about the eating behavior of women with breast cancer. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine whether breast cancer patients and healthy controls differ in their orthorexia nervosa levels and to determine any factors that affect orthorexia nervosa (socio-demographic variables and nutritional habits).

Method

The data were collected using a face-to-face interview technique between May 2018 and March 2019 at outpatient clinics and a family health center in Turkey. The data of the study were collected using personal information form and the Orthorexia Nervosa Scale (ORTO-15). A linear regression analysis was performed to investigate the effects of socio-demographic variables and nutritional habits of women on the risk of orthorexia nervosa.

Results

Breast cancer patients had significantly lower ORTO-15 scores (i.e., a higher orthorexia risk) than the healthy controls. For the cancer patients, a regression analysis revealed that ORTO-15 scores were significantly associated with education level, organic food consumption status, receipt of social support for care, and presence of a chronic disease other than cancer. In the healthy controls, body mass index and education level were the primary predictors of ORTO-15 scores.

Conclusion

The higher orthorexia risk of cancer patients has implications for these patients that could be improved through nutritional counseling.

Level of Evidence: III, case-control study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer is a disease characterized by uncontrolled cell proliferation [1] resulting from a variety of genetic, environmental, and personal factors [2] that include an unhealthy lifestyle (e.g., high body mass index (BMI), low fruit and vegetable intake, lack of physical activity, smoking, and alcohol use) [3]. The precise links between weight and breast cancer are complex and still emerging [4]. Experts report that healthy weight and eating a healthy diet should be maintained to reduce the risk of breast cancer and other chronic diseases [5,6,7]. But general population surveys report a low awareness (5–12%) of the link between obesity and lifestyle factors and breast cancer risk [8]. Cancer is one of the most important health problems today due to its lengthy and costly treatment and often severe negative side effects (e.g., pain, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, fatigue, depression) [9, 10], in addition to its high prevalence and mortality rate [11]. In fact, cancer is the second most common cause of death for known reasons after cardiovascular disease [3], and breast cancer is the most common cancer type and the leading cause of death in women [1].

Cancer patients are recommended to follow a diet that is high in fruits and vegetables and is low in foods that are processed or have large amounts of saturated fat or sugar [12]. However, the pressure to comply with a nutrition program may lead to the development of harmful attitudes in terms of food and body weight. People with chronic diseases such as cancer may be more worried about their health, body weight, and dietary practices than healthy people because they want to improve their health and not deteriorate [13]. An increased focus on the relationship between diet and their disease may lead to inappropriate or corrupt eating behavior, emotional eating, restrictive eating, strict dieting, healthy eating concerns, or body weight control through inappropriate balancing behaviors; all of these behaviors may be precursors of eating disorders [14]. Cancer survivors’ health behavior plays a crucial role in the context of these posttreatment demands and tertiary prevention contributing to recurrence risk reduction. Health behavior, including weight control, smoking cessation, increase of physical activity, and moderating alcohol intake, could reduce breast cancer risk by approximately 30% [15, 16]. According to the research conducted by Oberguggenberger et al. in [17], a breast cancer diagnosis is associated with eating disturbances and overweight in the long run.

Healthy nutrition habits are not a pathological condition, but being highly engaged in health food consumption, spending too much time preparing foods, and losing functionality in daily life due to this situation can be classified as a disease related to behavior and personality [18, 19]. The term “orthorexia” is derived from the words “orthos” (correct) and “orexis” (appetite) and means an obsession with healthy and proper eating [20]. The pursuit of an “extreme dietary purity” due to an exaggerated focus on food may lead to a disordered eating behavior called “orthorexia nervosa” (ON) [21]. According to Bratman, orthorexia is a pathological obsession with a state of anxiety over proper nutrition with the intent to protect and improve health [22]. Although the American Psychiatric Association has not yet identified orthorexia as a disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) [23, 24], Dunn and Bratman [22] have proposed a set of diagnostic criteria, with the first major one being a pathological obsession with proper nutrition for the purpose of protecting and improving health. “Criterion A; obsessive focus on “healthy” eating, marked by exaggerated emotional distress in relationship to food choices perceived as unhealthy; weight loss may ensue as a result of dietary choices, but this is not the primary goal.” [22]. Accordingly, individuals with orthorexia obsessively were dietary restrictions escalate over time, and may come to include elimination of entire food groups and involve progressively more frequent and/or severe “cleanses” regarded as purifying or detoxifying. This escalation commonly leads to weight loss, but the desire to lose weight is absent, hidden or subordinated to ideation about healthy eating [19]. In time, these dietary rules may become even more restrictive and lead to malnutrition. Moreover, people with orthorexia experience extreme anxiety and other negative feelings if they violate any of their strict dietary rules, as well as psychosocial impairments in their daily lives [19].

Breast cancer is one of the most important health problems in women. The most common type of cancer with the highest mortality rate in Turkey is breast cancer. Therefore, women with breast cancer were studied with this group to evaluate their eating attitudes. The aim of this study was to compare the orthorexia nervosa levels of women with and without breast cancer and also to assess whether those orthorexia nervosa levels are associated with various some socio-demographic (age, education level) and some nutrition variables (herbal product consumption status, consuming organic foods).

Hypothesis

In women with breast cancer, the risk of orthorexia nervosa is expected to be higher than in healthy women.

In studies on cancer patients, after diagnosis, it was found that patients restrict fat intake and red meat consumption in their diets, increase fiber consumption and fruit and vegetable consumption, they consume more vegetable products and in short, they make more effort for healthy nutrition [16, 25,26,27,28,29]. All these findings in the literature make us think that women will give more importance to healthy nutrition after the diagnosis of breast cancer and their nutrition anxiety will be higher.

Methods

Participants

The study population consisted of patients diagnosed with breast cancer who were inpatients of the Medical Oncology Service of a university hospital with the largest oncology center in the eastern region of the country. The sample included 238 patients who were selected for the sample group using a simple random sampling method from the probability sampling methods. There were 497 breast cancer patients registered to the hospital at the time of the study. The minimum sample size of the study was determined to be 238 people based upon a power analysis, and the power of representation was 0.95 at the 95% confidence interval (CI). A list of patients was used to choose those to be sampled with a random numbers table.

The control group contained women 18 years or older who were enrolled in a Primary Health Center and who had not been diagnosed with cancer. A sample of 164 women was selected using the improbable sampling method. The data for the control group were collected at the Primary Health Center, which is the largest center of the province in which the study was conducted. Women were not diagnosed with any cancer but had chronic disease (hypertension, diabetes and epilepsy) other than cancer. These centers are primary health care institutions where preventive health services are provided for individuals.

Procedure

Ethical considerations

To conduct the study, written permission was obtained from Health Sciences Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee (2018-21/15). In addition, the patients provided written informed consent. The data were collected using a face-to-face interview technique between May 2018 and March 2019 at the clinics and primary care health center where the study was conducted. The participants were informed about the purpose of the study and given the questionnaires to fill out. An explanation was made for any questions that the participants did not understand without commenting. Each interview lasted for approximately 10–15 min.

Materials

The data of the study were collected using a personal information form to obtain the demographic characteristics and eating habits of women with breast cancer and healthy women. The Orthorexia Nervosa Scale (ORTO-15) was also administered to determine the orthorexic risks.

Information form The participants were asked seven questions to determine their socio-demographic characteristics including age, education level, marital status, working status, family income, receiving support in care, and the presence of chronic disease. The remaining questions on this form asked for self-reported height and weight that were used to calculate body mass index (BMI) and asked about whether or not they consumed during the past week (a) any herbal products, (b) any organic foods, and (c) any unhealthy foods.

The ORTO-15 Scale is a 15-question Likert-type scale that was developed by Donini et al. [30] in 2005 based on the questionnaire prepared by Bratman and Knight [31] to assess the tendency for orthorexia nervosa. We used the Turkish translation of the ORTO-15 [32]; in the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.79, which demonstrated good internal consistency. The questions are answered using a 4-point Likert-type scale (always, often, sometimes, and never) to investigate the obsessive behaviors of individuals in selecting, buying, preparing, and consuming the foods they describe as healthy. While the answers that are the distinguishing criteria for orthorexia were scored as “1,” the answers showing normal eating behavior tendencies were scored as “4.” Thus, the ORTO-15 scores could range from a minimum of 15 to a maximum of 60, with lower scores representing higher levels of orthorexia. The Cronbach’s alpha value of the scale in that prior study was 0.44 [32]. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha value of the scale was 0.79. The scale was taken as ≤ 33 in this study since the scale threshold value was ≤ 33.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0 was used to analyze the study data. First, Chi-square analyses and t tests were conducted to determine whether the breast cancer patients and healthy controls differed on any of the socio-demographic and ORTO-15 variables. Second, separately for each group, Pearson r analyses, t tests, and analyses of variance were conducted to determine how the ORTO-15 scores were associated with the various socio-demographic and nutrition variables. Finally, the significant predictors from those analyses were then entered into a linear regression analysis separately for each group. In the present study, the results at a 95% CI and a significance level of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

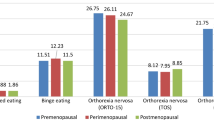

The socio-demographic characteristics and dietary habits of the women in the cancer patient and the control groups were compared (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups. A significantly higher percentage of the breast cancer patients (23.5%) than the healthy controls (6.7%) were categorized as having a high risk of orthorexia (i.e., ORTO-15 score ≤ 33; Table 2). Comparable results were found with the t test, whereby the mean ORTO-15 scores were significantly lower for breast cancer patients (M = 40.5, SD = 7.43) than for the healthy controls (M = 43.26, SD = 8.60) (Table 2).

As shown in Table 3, for both the cancer patients and the healthy controls, ORTO-15 scores were significantly associated with education level, income level, and presence versus absence of a chronic disease other than cancer. Specifically, ORTO-15 scores were lower (i.e., higher risk of orthorexia) for those with higher levels of education including a university degree, for those with higher income levels, and for those who had a chronic disease other than cancer. Additionally, for the cancer patients but not the healthy controls, ORTO-15 scores were lower for those who received support during their care, for those who believed that unhealthy nutrition is a cause of cancer, and for those who ate organic foods. Finally, for the healthy controls but not the cancer patients, ORTO-15 scores were lower for those with lower BMIs and for those who were younger (Tables 4 and 5).

When the significant predictors from the above-mentioned analyses were entered into regression analyses, for the cancer patients, the only significant predictors were education level, receiving support in care, presence of a chronic disease other than cancer, and a diet that includes eating organic foods. For the healthy controls, the only significant predictors were education level and BMI (Table 5).

Discussion

In the current study, women with breast cancer had a mean ORTO-15 score of 40.5, and 23.3% of them had a high risk for orthorexia nervosa, which is comparable to 22.9% of diabetic patients in a different study [33]. In contrast, the women in the control group had a mean ORTO-15 score of 43.3, and only 6.7% of them had a high risk for orthorexia nervosa, which is consistent with Donini et al.’s finding of a prevalence rate of 6.9% in a non-clinical sample [34]. These differences between the women with and without breast cancer were statistically significant, supporting this study’s hypothesis that orthorexia nervosa risk is higher in women with breast cancer, in comparison to women in a healthy control group. Diet plays an important role in the treatment of many chronic diseases (diabetes mellitus, cancer, etc.). Patients’ failure to comply with their recommended diet may adversely affect the course of chronic diseases, such as diabetes and cancer, as well as symptom management. All of these reasons may cause individuals with chronic diseases to have a greater risk of orthorexia nervosa. A higher awareness for weight control and increased dietary efforts can lead, among others, to the development of eating disorders or even eating disorders [35]. In addition, weight control and healthy diets are experienced as mediating factors for breast cancer’s in terms of controlling disease recurrence. A change in eating behavior has previously been described following a breast cancer diagnosis of higher dietary restrictions for the purpose of disease control [36, 37].

We found that education was an important factor in orthorexia nervosa in both cancer patients and healthy women. Conflicting results have been obtained in studies investigating the correlation between educational level and orthorexia nervosa [38,39,40]. According to Donini et al., it was reported that the prevalence of orthorexia in those with a low educational level was higher than it was for those with a high educational level [34]. In a study conducted by Karakuş et al. of university students studying in their department of nutrition and dietetics, it was determined that the mean ORTO-11 scale score of fourth-year students was lower than that of first-year students (i.e., they had higher orthorexic tendencies), but the difference was not statistically significant [41]. Bağcı Bosi et al. determined that people who were educated more about healthy eating tended to adhere to healthy and proper nutrition and focused on healthy eating [42]. An analysis of women with different educational levels was important in this study in terms of evaluating the effectiveness of the educational level on the orthorexia nervosa risk.

In this study, it was found that women receiving social care support had a negative effect on the level of orthorexia nervosa, such that the breast cancer patients who received social support during their care actually exhibited greater orthorexia nervosa symptoms. Social support helps to reduce the detrimental effect of negative events in life on physical health and well-being, and acts as a buffer against stress due to these negativities. Thus, it not only protects the individual from the negative results of the stress but also allows the person to stay healthy and feel good in every condition by supporting her emotions, such as belonging, self-confidence, and self-esteem [43]. Gülcivan and Topçu found that there was a significant correlation between the status of supporting and the interpersonal relationships subscale and healthy lifestyle behaviors in patients with breast cancer (p < 0.05) [44]. In the current study, it was observed that the majority of caregivers of women were their husbands and children. It is thought that women who receive social support could increase their risk of orthorexia nervosa by giving more importance to nutrition to get well and stay healthy.

There was also a decrease in the orthorexia nervosa scores of women with chronic diseases other than cancer. Physical and emotional problems, such as taste changes, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, dehydration, mucositis, dryness of the mouth, fatigue, depression, and anxiety from the significant side effects of cancer treatment, are intensively experienced by women [9]. Because these symptoms affect food intake in particular, patients are faced with malnutrition problems [9]. The presence of another chronic disease (such as hypertension) along with these symptoms in women with breast cancer makes individuals more susceptible to changes in food consumption. Because of all these reasons, the presence of another chronic disease along with cancer is considered to increase the orthorexic nervosa risk of women.

In the present study, 79.5% of female cancer patients thought that unhealthy nutrition caused cancer. In a study conducted by Ansa et al. in women with recurrent breast cancer, a statistically significant correlation was identified between an unhealthy nutrition status and cancer recurrence [45]. In studies that investigated healthy individuals in the literature, a statistically significant difference was observed between caring about proper nutrition statuses and orthorexia nervosa levels [46]. In the literature studies; women with breast cancer stated that cancer is the cause of unhealthy dietary habits. In addition, cancer women were found to have more nutrition, weight and appearance concerns than healthy women [47,48,49]. In the study of Lin et al., it was found that approximately half of the participants were overweight or obese (46%) and eating a healthy diet (53%) had a too much effect on cancer development [50]. In that study, the fact that women with breast cancer thought that unhealthy eating caused cancer and also attached more importance to the preparation of foods to reduce the symptoms of cancer treatment (such as nausea and vomiting) may have increased their orthorexia nervosa risk.

It was found that the organic food use status of the cancer patients had a negative effect on the level of orthorexia nervosa, such that the women who consumed organic foods exhibited greater orthorexia nervosa symptoms. In women with cancer diagnosis; thinking that there is a direct relationship between nutrition and cancer, seeing organic nutrition as the main condition for coping with diseases, as well as cancer treatment may also have raised the concerns of Orthorexia Nervosa.

In this study, the BMI of women in the control group was found to be effective at predicting the level of orthorexia nervosa. In the literature, BMI was found to be effective on orthorexia nervosa behaviors [18, 31, 51]. Social interactions and media encourage a “thin” body, and therefore lead to increasing concerns about body weight and body image. These concerns may have led to a decrease in average scores in orthorexia nervosa.

Limitations

It should be acknowledged that the study faces a number of limitations that should be accounted for addressed in future research.

-

Orthorexia neurosis (ON); the American Psychiatric Association (APA) publication DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) has not yet been described as a disease, as there are no clear diagnostic criteria such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.

-

ORTO-15 does not distinguish between healthy eating and pathologically healthy eating.

-

ORTO-15 scale of world literature and different threshold values in studies in Turkey (33, 35, 40) are available. Since there is no standard threshold value, this study was conducted on the total score.

-

This study evaluated only patients admitted to a hospital in Malatya and healthy individuals in a family health center. Patients living in other parts of the country may have different characteristics. However, in this study, the selected hospital was a national referral center. The Primary Health Center also had a population of over 10.000 people. To overcome the limitation, the researchers tried to increase the sample variance.

-

Since the mother tongue of the researcher was Turkish, those who could not speak Turkish (Kurdish patients and Syrian migrant patients) were not included in the survey.

-

To evaluate the differences between the orthorexia nervosa level of healthy and patient groups, we recommend that more studies should be carried with larger sample groups and different patient groups (hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, etc.)

Conclusion

According to these results, while 23.5% of female cancer patients had a risk of orthorexia nervosa, only 6.7% of the women in the control group had this same risk. It was found that for female cancer patients, the mean scores (40.5 ± 7.43) of the ORTO-15 scale were lower than that of the control group (43.26 ± 8.60). A lower ORTO-15 score indicates that women with cancer have a higher risk of orthorexia nervosa. In the study, the factors affecting the levels of orthorexia nervosa of the women in the cancer patients to the orthorexia nervosa were finally determined: level of education, having a disease other than cancer, perceived social support, and organic food consumption status. It was determined that BMIs and education levels were effective on the orthorexia nervosa levels of women in the control group. This trend shows us that there are significant differences between the patients and healthy women with orthorexia nervosa levels and the factors that affect it. Orthorexia nervosa is not supposed to be a very harmful condition, especially not in comparison to having cancer. An increased risk of orthorexia nervosa is possible as a side effect of the disease and chemotherapy in cancer patients.

According to these results, training programs to raise awareness in women about obsessions with healthy eating and seminars specific to this group should be organized. More attention should be given to women having many nutrition problems due to cancer, while also informing them about nutrition. The matters of healthy nutrition and the preparing and cooking of foods should be emphasized, and any wrong or missing information should be corrected. Since this type of eating disorder is a new concept, effective treatment methods should be developed to effectively reduce or eliminate the problem.

Clinical Implications

In the study, which investigated the nutritional obsessions of cancer patients, it was determined that the nutritional obsessions risk of women was high. This study is important for nurses to focus on nutrition while giving care to cancer patients. In the clinic, working with other health disciplines could relieve patients’ concerns about nutrition issues (e.g., dietitian, psychologist).

References

American Cancer Society. Breast cancer facts & figures 2017–2018. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc.2017. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-andstatistics/breast-cancer-facts-andfigures/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2017-2018. pdf. Accessed 20 Sept 2018

National Cancer Institute (NCI). Research on Causes of Cancer, 2015. Available from https://www.cancer.gov/research/areas/causes Accessed 20 Sept 2018

World Health Organization (WHO). Cancer, 2018. http://www.who.int/news room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer. Accessed 20 Sept 2018

Cecchini RS, Costantino JP, Cauley JA et al (2012) Body mass index and the risk for developing invasive breast cancer among high-risk women in NSABP P-1 and STAR breast cancer prevention trials. Cancer Prev Res 5:583–592. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0482

Cancer Research UK. Definite breast cancer risks. N.D. Available from http://cancerhelp.cancerresearchuk.org/type/breast-cancer/about/risks/definite-breast-cancer-risks#weight. Accessed 5 July 2019

World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. Washington DC 2007. Available from: http://www.dietandcancerreport.org/cancer_resource_center/downloads/chapters/chapter_12.pdf. Accessed 5 July 2019

Sauter ER (2018) Breast cancer prevention: current approaches and future directions. Eur J Breast Health 14(2):64–71. https://doi.org/10.5152/ejbh.2018.3978

Grunfield EA, Ramirez AJ, Hunter MS, Richards MA (2002) Women’s knowledge and beliefs regarding breast cancer. Br J Cancer 86:1373–1378. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6600260

Ünsar S, Yıldız FÜ, Kurt S et al (2007) Home care and symptom control in cancer patients. Fırat Health Servi J 2(5):89–106

Piamjariyakul U, Williams PD, Prapakorn S et al (2010) Cancer therapy-related symptoms and self-care in Thailand. Eur J Oncol Nurs 14(5):387–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2010.01.018

Gürsu RU, Kesmezacar Ö, Karaçetin D, Mermut Ö, Ökten B, Güner Şİ (2012) Istanbul research and training hospital oncology division: 18-month results of a newly formed unit. Istanb Med J 13(1):13–18. https://doi.org/10.5505/1304.8503.2012.55264j.eatbeh.2012.02.003

Demir Ç, Onat H (2011) Nutrition in a patient with cancer-I. In: Mandel NM, Onat H (eds) Approach to cancer patients: diagnosis, treatment, follow-up problems. 2. Nobel Medical Bookstore, Istanbul, pp 489–503

Quick VM, McWilliams R, Byrd-Bredbenner C (2012) Case–control study of disturbed eating behaviors and related psychographic characteristics in young adults with and without diet-related chronic health conditions. Eat Behav 13:207–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.02.003

Grilo C (2006) Eating and weight disorders. Psychology Press, New York

Panjari M, Bell RJ, Davis SR (2011) Sexual function after breast cancer. J Sex Med 8:294–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010-02034.x

Wright CE, Harvie M, Howell A, Evans DG, Hulbert-Williams N, Donnelly LS (2015) Beliefs about weight and breast cancer: an interview study with high risk women following a 12 month weight loss intervention. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 13:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-014-0023-9

Oberguggenberger A, Meraner V, Sztankay M et al (2018) Health behavior and quality of life outcome in breast cancer survivors: prevalence rates and predictors. Clin Breast Cancer 18(1):38–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbc.2017.09.008

Fidan T, Ertekin V, Işıkay S, Kırkpınar I (2015) Prevelance of orthorexia among medical students in Erzurum Turkey. Compr Psychiatry 51(1):49–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.03.001

Chaki B, Pal S, Bandyopadhyay A (2013) Exploring scientific legitimacy of orthorexa nervosa: a newly emerging eating disorder. J Hum Sport Exerc (JHSE) 8:1045–1053. https://doi.org/10.4100/jhse.2013.84.14

Varga M, Thege BK, Dukay-Szabó S, Túry F, Van Furth EF (2014) When eating healthy is not healthy: orthorexia nervosa and its measurement with the ORTO-15 in Hungary. BMC Psychiatry 28:14–59. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-59

Cena H, Barthels F, Cuzzolaro M et al (2019) Definition and diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa: a narrative review of the literature. Eat Weight Disord 24(2):209–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40519-018-0606-y

Dunn TM, Bratman S (2016) On orthorexia nervosa: a review of the literature and proposed diagnostic criteria. Eat Behav 21(11–17):70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.12.006

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub

Dunn TM, Gibbs J, Whitney N, Starosta A (2017) Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa is less than 1%: data from a US sample. Eat Weight Disord 22(1):185–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0258-8

Rock CL, McEligot AJ, Flatt SW et al (2000) Eating pathology and obesity in women at risk for breast cancer recurrence. Int J Eat Disord 27:172–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(200003)27:2%3CI172

Rock CL, Demark-Wahnefried W (2002) Nutrition and survival after the diagnosis of breast cancer: a review of the evidence. J Clin Oncol 20:3302–3316. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2002.03.008

Cade JE, Burley VJ, Greenwood DC (2007) Dietary fibre and risk of breast cancer in the UK women’s cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 36:431–438. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dy1295

Blanchard CM, Denniston MM, Baker F et al (2003) Do adults change their lifestyle behaviors after a cancer diagnosis? Am J Health Behav 27(3):246–256. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.27.3.6

Satia JA, Campbell MK, Galanko JA, James A, Carr C, Sandler RS (2004) Longitudinal changes in lifestyle behaviors and health status in colon cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 13(6):1022–1031 (http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/content/13/6/1022)

Donini LM, Marsilli D, Graziani MP, Imbriale M, Canella C (2005) Orthorexia nervosa: validation of a diagnosis questionnaire. Eat Weight Disord 10(2):e28–e32. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03327537

Bratman S, Knight D (2000) Health food junkies: overcoming the obsession with healthful eating. Broadway Books, New York

Arusoğlu G, Kabakçi E, Köksal G, Merdol TK (2008) Orthorexia nervosa and adaptation of ORTO-11 into Turkish. Turk J Psychiatry 19:283–291

Atalay NG, Kızıltan G (2015) Determination of the relationship between orthorexia nervosa, eating behavior disorders in adult type 1 diabetic individuals under carbohydrate counting diet and biochemical and anthropometric measurements. Başkent University, Health Sciences Institute, Department of Nutrition and Dietetics. Doctoral Thesis, 2015. Ankara

Donini LM, Marsili D, Graziani MP, Imbriale M, Cannella C (2004) Orthorexia nervosa: a preliminary study with a proposal for diagnosis and an attempt to measure the dimension of the phenomenon. Eat Weight Disord 9(2):151–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03325060

French SA, Perry CL, Leon GR, Fulkerson JA (1994) Food preferences, eating patterns, and physical activity among adolescents: correlates of eating disorders symptoms. J Adolesc Health 15:286–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/1054-139X(94)90601-7

Rabin C, Pinto B (2006) Cancer-related beliefs and health behavior change among breast cancer survivors and their first-degree relatives. Psychooncology 15:701–712. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1000

Thomson CA, Thompson PA (2009) Dietary patterns, risk and prognosis of breast cancer. Future Oncol 5:1257–1269. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon.09.86

Ramacciotti CE, Perrone P, Coli E et al (2011) Orthorexia nervosa in the general population: a preliminary screening using a self-administered questionnaire (ORTO-15). Eat Weight Disord 16(2):e127–e130. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03325318

Aksoydan E, Camci N (2009) Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among Turkish performance artists. Eat Weight Disord 14(1):33–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03327792

McInerney-Ernst E M. Orthorexia nervosa: real construct or newest social trend? USA: ProQuest Information & Learning; 2012. Available from http://hdl.handle.net/10355/11200. Accessed 20 Sept 2018

Karakus B, Hidiroglu S, Keskin N, Karavus M (2017) Orthorexia nervosa tendency among students of the Department of Nutrition and Dietetics at a university in Istanbul. North Clin Istanb 4(2):117–123. https://doi.org/10.14744/nci.2017.20082

Bağcı Bosi AT, Çamur D, Güler C (2007) Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa in resident medical doctors in the faculty of medicine (Ankara, Turkey). Appetite 49(3):661–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2007.04.007

Şahin D (1999) Support And Health. Edt., Okyayuz UH Health Psychology, 1st edn. Social Turkish Psychological Association Publications, Ankara, pp 79–106

Gülcivan G, Topçu B (2017) Quality of lıfe with breast cancer patıents and evaluatıon of healthy life behaviors. Namık Kemal Med J 5(2):63–74

Ansa B, Wonsuk Yoo W, Whitehead M, Coughlin S, Smith S (2016) Beliefs and behaviors about breast cancer recurrence risk reduction among African American breast cancer survivors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13(46):2–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13010046

Arslantaş H, Adana F, Öğüt S, Ayakdaş D, Korkmaz A (2017) Relationship between eating behaviors of nursing students and orthorexia nervosa (obsession with healthy eating): a cross-sectional study. J Psychiatr Nurs 8(3):137–144. https://doi.org/10.14744/phd.2016.36854

Oberguggenberger A, Meraner V, Sztankay M et al (2018) Health behavior and quality of life outcome in breast cancer survivors: prevalence rates and predictors. Clin Breast Cancer 18(1):38–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbcc2017c09.008

Hossein SA, Bahrami M, Mohamadirizi S, Paknaad Z (2015) Investigation of eating disorders in cancer patients and its relevance with body image. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 20:327–333. https://doi.org/10.4103/1735-9066.256650

Rabin C, Pinto B (2006) Cancer-related beliefs and health behavior change among breast cancer survivors and their first-degree relatives. Psycho-oncology 15(8):701–712. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1000

Lin A, Finch L, Stump T, Hoffman S, Spring B (2019) Cancer prevention beliefs and diet behaviors among females diagnosed with obesity-related cancers (FS13-06-19). Curr Dev Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzz030.FS13-06-19

Gezer C, Kabaran S (2013) The risk of orthorexia nervosa for female students studying nutrition and dietetics. SDU J Health Sci Inst 4(1):14–22

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the patients who participated voluntarily in this study conducted at the Medical Center the patients for the support showed research conducted.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Ethical approval

This study, written permission was obtained from Health Sciences Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee (2018-21/15).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all the individual participants before they were included in this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of topical collection on Orthorexia Nervosa.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aslan, H., Aktürk, Ü. Demographic characteristics, nutritional behaviors, and orthorexic tendencies of women with breast cancer: a case–control study. Eat Weight Disord 25, 1365–1375 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00772-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00772-y