Abstract

Objectives

Appetite is a subjective essential sense. In patients with severe anorexia nervosa (AN), controversy remains whether this sensation is altered. The objectives were to clarify, in patients with severe AN: (1) Whether the appetite changes during partial weight restoration, (2) Whether potential changes in appetite are related to (i) diagnostic subtype of AN, (ii) psychopharmacological treatment, (iii) disease duration, (iv) duration of hospitalization, and (v) baseline body mass index (BMI).

Methods

The study consisted of 39 patients, with a mean age of 23.7 ± 8 and an admission mean BMI of 13.1 ± 2.0 kg/m2. The patients were consecutively admitted to a specialized somatic nutrition unit between 2015 and 2016. They were asked to rate their hunger and satiety on a numeric visual analog scale (VAS), before and after a lunch meal at admission and at discharge in the same standardized environment. The patients could participate more than once if readmitted, resulting in a total of 119 observed meals. Data were analyzed in a regression model for repeated measures.

Results

At admission, changes in hunger and satiety perception were weak. After weight gain of 10.4% ± 8.5% within a median of 26 (IQR: 25) days, there was a slight increase in hunger perception, p = 0.049. However, there was no detectable change in satiety perception. There was no noticeable correlation between appetite change and psychopharmacological treatment, diagnostic subtype, BMI, duration of hospitalization, and disease duration.

Conclusion

Hospitalized patients with severe AN exhibit strikingly weak changes in hunger and satiety perception during standardized and supervised meals.

Level of evidence

Level IV, evidence obtained from multiple time series analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a syndrome defined by restriction of energy intake leading to significantly low body weight (in context of what is minimally expected for age, sex, developmental trajectory, and physical health), an intense fear of gaining weight or of becoming fat, and distorted body image [1]. Two clinical subtypes are defined: a restricting type and a binge-purging type. The binge-purging type is defined by a constant obsession with eating and episodes of eating large amounts of food in a short time period, and/or self-induced vomiting or other purging behaviors [1]. The syndrome has been known since 1873 [2]; however, the etiology remains to be clarified. AN occurs in very different degrees of severity [1], with secondary endocrine and metabolic adaptive changes and disturbances [3].

Anorexia means loss of appetite; however, in AN, there is disagreement about whether the appetite is changed or not. Appetite is a subjective essential sense, which is regulated in a complex ensemble between brain, stomach–intestinal system, and hormones. As a direct result of malnutrition, there are many somatic complications, as patients with AN adapt to starvation [4]. Several of these complications may affect hunger and satiety perception. An example of this is delayed gastric emptying and constipation which can cause nausea and early satiety [4]. In addition to this, patients with AN who vomit may experience having difficulty swallowing because of epigastric discomfort and heartburn which may lead to loss of appetite [4].

Furthermore, changes in the hormone systems in patients with AN affect the biological “reward system” in the brain, which plays a significant role in appetite regulation. Hypothalamic and mesolimbic endocannabinoids enhance appetite by stimulating neurochemical pathways underlying both homeostatic and rewarding aspects of food intake [5, 6]. Endocannabinoids are involved in food-related reward mechanisms, and there is evidence that these mechanisms are dysregulated in patients with AN [5, 6]. Functional neuroimaging studies have demonstrated decreased food-related stimuli in brain areas of the mesolimbic reward system in patients with AN compared to healthy controls. Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal dysregulation is associated with altered subjective appetite and food motivation brain circuits in AN [7, 8].

Hunger and satiety may be influenced by sensory factors and palatability, including taste and smell. Previous studies reported an altered perception of olfactory and gustatory stimuli in patients with AN [9, 10] and a recent systematic review of the findings suggest that individuals with AN may experience reduced taste sensitivity that may improve following recovery [11]. These findings suggest that gustatory and olfactory dysfunction are directly associated with hunger, malnutrition, and low-weight status.

VAS measurements have been shown to be a reliable scale for measuring perceived hunger and satiety in healthy subjects and in different forms of malnutrition patients [12]. However, only a few studies have investigated subjective hunger and satiety perception in patients with AN. So far, no clear consensus has been established as to which refeeding treatment causes appetite changes. The earliest of these studies showed that patients with AN perceived hunger in a manner similar to healthy controls, but reported higher levels of anxiety when hungry. Over half of the patients with AN lacked satiety perception at the end of a meal [13]. Later studies have shown that patients with AN had weaker hunger perception [8, 14, 15] and stronger satiety perception, before and after a meal, compared to healthy controls [14, 15]. One study found that the lower the BMI, the lower the hunger levels and the higher the satiety levels [14]. Although ratings of hunger increased, and satiety decreased after nutritional rehabilitation at discharge pre-meal in patients with AN, their appetite remained considerably different than healthy controls at discharge [15]. The most recent study showed that 15 newly diagnosed adolescents with mild and moderate AN (BMI 17.7 ± 2.3) experienced higher satiety perception during and after a meal and lower hunger perception after a meal in patients with AN when refed compared to admission and compared to lean controls [16].

The few published studies [8, 13,14,15,16] revealed considerable inconsistencies in hunger and satiety perceptions in patients with AN. These discrepancies most likely result from substantial variability among studies, including issues related to sample (e.g., small size, durations of illness, duration of hospitalization, severity of AN, and mixed subgroups), study design (e.g., variable fasting duration before meals, non-standardized meals), and statistical and technical approaches (e.g., Hunger–Satiety questionnaire [13], VAS [8, 14, 15], and Satiety Labeled Intensity Magnitude (SLIM) [16]. There is clearly need for research that could lead to a clarification of the above-mentioned factors that may affect appetite in patients with severe AN. Thus, the objectives of this study were to clarify, in hospitalized patients with severe AN:

-

1.

Whether the appetite (in terms of subjective hunger and satiety) changes during partial weight restoration.

-

2.

Whether potential changes in appetite are related to (i) diagnostic subtype of AN, (ii) psychopharmacological treatment, (iii) disease duration, (iv) duration of hospitalization, and (v) baseline body mass index (BMI).

Thus, the present study increases our understanding of AN and could potentially lead to development of useful instruments for supplemental effect measures of treatments.

We hypothesized altered appetite during refeeding, as the impairments of the endocrine axes, gastrointestinal peristalsis and secretion, olfactory–gustatory functions, and the mesolimbic and hypothalamic factors are partially resolved.

Methods

Patient characteristics

Forty-seven patients with severe AN were consecutively admitted to a specialized somatic stabilization nutrition unit between 1st of February 2015 until 1st of June 2016 (Fig. 1). Eight patients were excluded due to somatic comorbidity (Fig. 1), and thirty nine were included with an average age of 23.7 years. Fourteen patients were admitted more than once during the study period.

The unit is integrated in Center for Eating Disorders in a multidisciplinary collaboration between psychiatric and nutritional expertise, and the study was conducted during treatment as usual which include adjusting the energy intake to ensure safe and effective weight restoration of 2.0–3.0% per week according to guidelines [17].

Inclusion criterion was patients with AN consecutively referred to a specialized ward. All patients fulfilled the criteria of DSM-5 [1]. As the objective of the study was to assess the effect of partial weight restoration on the perception of appetite, patients solely admitted for short-term water and electrolyte correction were excluded.

Because of premature discharge from the hospital, 15 patients did not participate in the numeric VAS measurements at discharge, resulting in a total of 119 observations (76 observations at admission and 43 at discharge) which all were analyzed (Fig. 1). The median hospital length of stay for all 43 observations was 26 (IQR: 25) days. The characteristics of the sample and psychiatric comorbidities of the participants are listed in Table 1. The mean duration of a diagnosis of AN before hospital admission was 6.5 ± 5.9 years. At admission to the somatic stabilization unit, the patients had a mean BMI 13.1 ± 2.0 kg/m2. During the hospital stay, mean BMI increased to 13.9 ± 1.6 kg/m2. Eight patients with somatic comorbidity were excluded, since both the illness and the medication for this may affect the appetite (Fig. 1).

Data collection

Data were extracted from the patients’ electronic medical records. We recorded medical history including age, sex, duration of hospitalization, disease duration, diagnostic subtype of AN, intake of psychopharmacological medications, and anthropometrics at hospital admission and at discharge (Table 1).

Anthropometrics

Weight was measured on a calibrated platform scale and height on a wall-mounted stadiometer. BMI was calculated as weight divided by height (kg/m2). As the study population includes adolescents, BMI may overestimate the degree of malnutrition. Therefore, percentage expected body weight (%EBW) was calculated from median BMI for age and gender, based on reference values for 0–45 year old Danes measured between 1965 and 1983 [18].

Measures and procedures

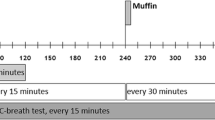

Hunger and satiety were measured using a numeric visual analog scale (VAS) (supplementary Figure), which is a horizontal line with numbers from 1 to 10 with labels on the extremities. Hospital nurses administered and collected the numeric VAS before and after a standardized lunch meal at admission and at discharge. All participants gave written consent to participate in the study, after the experimental protocol had been explained to them by a trained health care professional.

During the first week after admission, after stabilizing fluid electrolytes, patients were asked to rate their appetite using the numeric VAS. The patients were directed to mark the scale corresponding to their perceptions of hunger and satiety. Afterwards, the patients received a standardized lunch meal (1260 kJ, 50% carbs, fat 30%, and protein 20%) over the course of 30 min. To account for individual preferences in terms of specific foods, we offered a choice of 3–4 different meals. Immediately after the meal, the participants were asked to rate their hunger and satiety again. All measurements were performed in the same environment, at the same table with the same lighting, in the same room, which was kept free of odors and sounds as well as other factors that might influence the measurements (e.g., visual stimuli, individuals in the room). The meals were supervised by 2–3 specialized nurses to control that all meals were ingested. The patients required to complete all meals and were prevented from vomiting throughout treatment.

Statistical analysis

We carried out standard descriptive statistical analysis on patient characteristics. Data are shown as either mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR), depending on distribution. Delta VAS was calculated as the difference in perceived hunger or satiety from before to after the standardized meal and reported in boxplots. Power calculation was based on published studies of hunger and appetite assessment in patients with AIDS [19] and cancer [20], and on a cross sectional pilot study on patients with severe AN in our Nutrition Unit. To provide a power greater than β = 80% (type 2-error) and a significance of α = 5% (type 1-error) for observing a minimal relevant difference (MIREDIF) of 3 points, a minimum of 24 cases should be included.

Our main objective was to assess the effect of weight gain on hunger and satiety. We analyzed data in a multilevel linear regression model (multilevel modeling for repeated measures). We used a three-level model, as data were measured twice at each admission and individuals could have multiple admissions. Data were modeled linearly, and the model included both fixed (overall effects) and random effects (individual effects). The interpretation of the regression coefficient is the same as for linear models; a change in one unit of the independent variable (weight) will make the size of the coefficient change in the dependent variable (hunger or satiety). A p value below 0.05 indicates coefficients significant different from zero. In estimating the adjusted effect of weight gain, the model included percent of expected body weight at admission, relative gain in body weight and treatment with antipsychotics or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI).

Ethical approval

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Regional Committees on Health Research Ethics (file no. S-20162000-102) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (file no. 15/21461). The protocol is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT 02932046).

Results

Changes in appetite

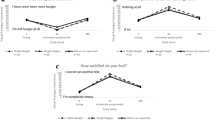

The hunger perception during the standardized meals was weak (Fig. 2a), whereas the satiety perception was high (Fig. 2b). The multilevel linear regression analysis revealed a small, but significant increase in the hunger perception during the weight gain of 3.3 ± 2.5 kg corresponding to a mean weight gain of 10.4% ± 8.5% (Table 2).

a The pre- and post-meal perception of hunger at admission and after weight gain. The hunger perception decreased during the meal; however, the meal responses were similar before and after minor weight gains. b The pre- and post-meal perception of satiety at admission, and after weight gain, as measured by VAS

The hunger perception decreased slightly during the meals; however, the meal responses were similar before and after the minor weight gains (Fig. 3). The distributions of the VAS responses pre- and post-meal at admission and at discharge are illustrated in Fig. 4.

There was no significant correlation between appetite change and psychopharmacological treatment, diagnostic subtype, duration of hospitalization, BMI, and disease duration (Supplementary Table 1). BMI at admission and percentage BMI change were significantly affected by multiple admissions; however, the appetite scores were not (Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

Through numeric VAS, this study sought to identify subjective appetite changes after weight gain and renutrition in patients with severe AN. After intensive renutrition with minor weight gain, the perception of pre- and post-meal hunger increased significant, whereas there were no significant changes in the satiety perception. The increase in hunger perception is consistent with previous studies [13, 15]. The lack of detectable change in satiety perception at discharge compared to admission is in line with prior studies of persistent dysregulated satiety perceptions in patients with AN following weight gain [13]. Contrary to our results, one study found that satiety perception decreased before a meal at discharge [15]. We did not find a noticeable correlation between appetite change and BMI, which is inconsistent with another study, where the lower the BMI, the lower the hunger perception and the higher the satiety perception (15.9 ± 2 kg/m2 at admission to 19.6 ± 0.8 kg/m2 at discharge) [14]. However, the included patients in our study all had very low BMI (13.1 ± 1.9 kg/m2 at admission to 13.9 ± 1.6 kg/m2 at discharge), which can explain the lack of correlation. Even after weight gain of 10% the patients still were severely underweight and did not change their way of subjectively perceiving hunger and satiety.

Psychiatric comorbidity is common in hospitalized patients with AN. In the present study, we chose to include the patients consecutively and did not exclude patients with psychiatric comorbidity. The regression analyses did not reveal significant correlations between occurrence of comorbidity and changes in appetite score, nor did it reveal correlations to psychopharmacologic treatments (data not shown). However, a definitive examination of the psychopharmacological effect on appetite would require an interventional design. We excluded patients with somatic comorbidity which presumably could influence appetite.

Our study involves, to our knowledge, the largest sample of patients with severe AN, for which meal experiences were evaluated during a supervised meal, at admission and at discharge. In addition, existing studies that have demonstrated differences in appetite perceptions included patients with variable disease duration, (e.g., patients with newly diagnosed AN) [16], which might affect appetite changes. Patients with a long duration of disease may have more disturbed appetite perceptions, as they have adapted to the changes in the brain, the gastrointestinal tract and hormones [4,5,6,7,8,9,10], which may affect the appetite negatively.

The duration of hospitalization and median of 26 (IQR: 25) days is comparable to previous studies which varies from an average of 6.4 days [16], several weeks [13, 14], to 5–11 weeks [15]. Duration of hospitalization potentially could affect the appetite. However, in our study, we chose to focus on weight changes rather than durations, as we expected weight gain to be a more potent mediator. Since the overall changes in appetite from admission to discharge were found to be strikingly weak, there hardly can be any significant effect of the duration of the hospitalization.

Accurate measurement of appetite in patients with AN is challenging, as subjective ratings of appetite in patients with AN are significantly different from controls, suggesting either denial of appetitive perceptions or marked inability to process internal hunger and satiety signals [21]. The ego-syntonic behavior of patients with AN may play a role, because starvation is integrated in the identity. Furthermore, it is suggested that patients with AN suffer from anhedonia, which is the inability to experience pleasure from activities usually found enjoyable [22] and might explain why patients feel neither hunger or satiety. This might explain the lack of significant differences in ratings of satiety perception between the patients with severe AN at admission and at discharge.

Our results are limited by not addressing anxiety response to food intake, which may occur and may affect the appetite [23, 24]. However, patients were supported by well-known staff and in safe terms and the meals were consumed under highly predictable conditions.

During hospital admission, patients are asked to choose between three or four different meals at each setting. In future studies investigating appetite, it might be interesting to study whether appetite sensation changes according to the meal offered.

We still find appetite highly relevant to monitor, knowing that it is influenced by multiple biological and psychological factors. In this study, the patients could be included multiple times. This was considered using multilevel modeling for repeated measures, and the sensitivity analysis confirmed that it did not change any conclusions. The use of healthy controls could have been assessed; however, in the longitudinal setting, the patients were their own controls.

The inclusion of males does, off course, add to the heterogeneity of our sample, but we still believe that the sample is fairly homogeneous in terms of disease severity and patient age. We believe that it adds to the external validity of our study. The literature on appetite does not, to our knowledge, suggest differences in satiety and hunger between genders. Potential gender differences in hunger and satiety perception is an interesting topic for further research.

A final limitation is the use of a numeric VAS. Although the numeric VAS has been found to be of comparable reliability to the simple VAS [25], it still implies a risk of floor-ceiling effect. The strength of the present study is the considerable number of highly standardized and supervised meals for patients with a severe degree of disease in a longitudinal setting.

Conclusion

In the present study, 39 patients with severe AN completed 119 standardized and supervised meals, upon which there were strikingly weak changes in hunger and satiety perception. After intensive renutrition with partial weight restoration, the perception of pre- and post-meal hunger increased slightly at discharge; however, there were no significant changes in the satiety perception at discharge compared to admission.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM), 5th edn. Arlington, VA

Gull WW (1873) Anorexia nervosa (apepsia hysterica, anorexia hysterica). Obes Res 5(5):498–502. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00677.x

Støving RK (2018) Mechanisms in endocrinology: anorexia nervosa and endocrinology: a clinical update. Eur J Endocrinol. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-18-0596

Westmoreland P, Krantz NJ, Mehler PS (2015) Medical complications of anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Am J Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.06.031

Støving RK, Andries A, Brixen K, Flyvbjerg A, Hørder K, Frystyk J (2009) Leptin, ghrelin, and endocannabinoids: potential therapeutic targets in anorexia nervosa. J Psychiatr Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.09.007

Monteleone AM, Di Marzo V, Aveta T, Piscitelli F, Dalle Grave R, Scognamiglio P, EL Ghoch M et al (2015) Deranged endocannabinoid responses to hedonic eating in underweight and recently weight-restored patients with anorexia nervosa. Am J Clin Nutr. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.096164

Holsen LM, Lawson EA, Blum J, Ko E, Makris N, Fazeli PK et al (2012) Food motivation circuitry hypoactivation related to hedonic and nonhedonic aspects of hunger and satiety in women with active anorexia nervosa and weight-restored women with anorexia nervosa. J Psychiatry Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.110156

Lawson EA, Holsen LM, DeSanti R, Santin M, Meenaghan E, Herzog DB, Goldstein JM et al (2013) Increased hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal drive is associated with decreased appetite and hypoactivation of food motivation neurocircuitry in anorexia nervosa. Eur J Endocrinol 10:639–647. https://doi.org/10.1530/eje-13-0433

Dazzi F, Nitto S, Zambetti G, Loriedo C, Ciofalo A (2013) Alterations of the olfactory-gustatory functions in patients with eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2238

Aschenbrenner K, Scholze N, Joraschky P, Hummel T (2008) Gustatory and olfactory sensitivity in patients with anorexia and bulimia in the course of treatment. J Psychiatr Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.003

Kinnaird E, Stewart E, Tchanturia K (2018) Taste sensitivity in anorexia nervosa: a systematic review. Int J Eat Disord. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22886

Flint A, Raben A, Blundell J, Astrup A (2000) Reproducibility, power and validity of visual analogue scales in assessment of appetite sensations in single test meal studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0801083

Garfinkel P (1974) Perception of hunger and satiety in anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med 4:309–315

Halmi KA, Sunday S, Puglisi A, Marchi P (1989) Hunger and satiety in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Ann N Y Acad Sci 575:431–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb53264.x

Andersen A, Stoner S, Rolls B (1996) Improved eating behavior in eating-disordered inpatients after treatment: documentation in a naturalistic setting. Int J Eat Disord. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199612)20:4%3c397:aid-eat7%3e3.0.co;2-i

Peterson CM, Tissot AM, Matthews A, Hillman JB, Peugh JL, Rawers E, Tong J et al (2016) Impact of short term refeeding on appetite and meal experiences in new onset adolescent eating disorders. Appetite 105:298–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.05.037

The Royal Colleges of Psychiatrists, Physicians and Pathologists Approved by Policy and Public Affairs Committee (PPAC) of the Royal College of Psychiatrists and by the Council of the Royal College of Physicians, CR189, 2nd edn (2014) Management of really sick patients with anorexia nervosa (MARSIPAN). https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr189.pdf?sfvrsn=6c2e7ada_2

Nysom K, Mølgaard C, Hutchings B, Michaelsen K (2001) Body mass index of 0 to 45-y-old Danes: reference values and comparison with published European reference values. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 25(2):177–184. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0801515

Lennie T, Neidig J, Stein K, Smith B (2001) Assessment of hunger and appetite and their relationship to food intake in persons with HIV infection. J Assoc Nurs AIDS Care 12(3):66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1055-3290(06)60145-3

Zietarska M, Krawczyk-Lipiec J, Kraj L, Zaucha R, Malgorzewicz S (2017) Nutritional status assessment in colorectal cancer patients qualified to systemic treatment. Contemp Oncol 21(2):157–161. https://doi.org/10.5114/wo.2017.68625

Huse D, Lucas A (1984) Dietary patterns in anorexia nervosa. Am J Clin Nutr 40(2):251–254. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/40.2.251

Davis C, Woodside B (2002) Sensitivity to the rewarding effects of food and exercise in the eating disorders. Comprehens Psychiatry 43(3):189–194. https://doi.org/10.1053/comp.2002.32356

Kissileff H, Brunstrom J, Tesser R, Bellace D, Berthod S, Thornton J, Halmi K (2016) Computerized measurement of anticipated anxiety from eating increasing portions of food in adolescents with and without anorexia nervosa: pilot studies. Appetite. 97:160–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.11.026

Steinglass JE, Sysko R, Mayer L, Berner LA, Schebendach J, Wang Y et al (2010) Pre-meal anxiety and food intake in anorexia nervosa. Appetite 55(2):214–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2010.05.090

Van Laerhoven H, Van der Zaag-Loonen H, Derkx B (2004) A comparison of Likert scale and visual analog scales as response options in children’s questionnaires. Acta Paediatr 93(6):830–835. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2004.tb03026.x

Acknowledgements

We thank Erik Christiansen for skilled statistic support and research nurse Kirsten Gitte Hansen for competent patient support during the meals.

Funding

This is a non-profit study, completely independent from commercial interests. The operating costs are very limited apart from the cost of the scholarship, which was supported by the Foundation of Psychiatry in southern Denmark.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RKS conceived the original idea, defined, and described the project as well as initiated data sampling. CK, JF, LAW, and RKS all contributed substantially to the analysis and interpretation of the data. CK wrote the first draft of the manuscript. CK, JF, LAW, and RKS all critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have provided approval of the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have nothing to declare.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Klastrup, C., Frølich, J., Winkler, L.AD. et al. Hunger and satiety perception in patients with severe anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord 25, 1347–1355 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00769-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00769-7