Abstract

Purpose

According to the Cognitive-Interpersonal Maintenance Model of anorexia nervosa, social factors are involved in the maintenance and development of this disorder. Therefore, this study aimed to test whether patients with restrictive-type anorexia nervosa (AN-R) experience malicious envy (negative emotions associated with the wish that others lack their superior quality), benign envy (negative emotions associated with the desire to reach and obtain the others’ superior quality) and Schadenfreude (pleasure at the misfortunes of others) with a higher intensity than healthy controls (HC).

Methods

26 AN-R patients and 32 HC completed scenarios that aimed to induce envy and Schadenfreude and completed questionnaires measuring envy, self-esteem and social comparison.

Results

AN-R patients reported more benign envy than HC. Interestingly, higher body mass index (BMI) was associated with less Schadenfreude, malicious and benign envy in AN-R only.

Conclusions

This study shows that AN-R patients present higher motivation to evolve when facing others’ superior quality (i.e., benign envy). It also underlines the importance of considering social factors in the maintenance of AN-R and the role of BMI when examining emotions related to others’ fortune.

Level of evidence

Level III, case-control analytic study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Interpersonal functioning is considered as a key etiological factor explaining both the development and maintenance of eating disorder (ED) symptoms [1,2,3]. In line with the Cognitive-Interpersonal Maintenance Model [4], anorexia nervosa (AN) results from a combination of vulnerability and maintenance factors that include cognitive, emotional and social features such as lack of mental flexibility, compulsory behaviours, greater reactivity to stress and insecure attachment or social avoidance. According to the meta-analysis conducted by Caglar-Nazali et al. [5], individuals with AN experience significant impairments in core facets of social processing, especially perceived social inferiority, sensitivity to social dominance, and reduced self-agency. Supporting the observed social difficulties in AN patients, especially in AN patients with a restrictive form (AN-R), studies have shown that AN-R is associated with impaired recognition of emotional expressions and more facial avoidance [5], cold social responses [1], increased physical distance for comfortable social interactions [6] and higher social anhedonia [7]. According to Treasure and Schmidt [4], social impairments might deteriorate the social interactions of AN-R subjects, increase their social isolation and worsen their symptomatology.

In this project, we focused on social emotions that might have a deleterious impact on AN-R social interactions. Specifically, we examined whether AN-R patients are particularly prone to experiencing envy and Schadenfreude, which are emotions related to the fortune of others or evoked by social comparison [8]. Envy is a negative emotion that “occurs when a person lacks another’s superior quality, achievement, or possession and either desires it or wishes that the other lacked it” [9]. This definition thus suggests that there are two sub-types of envy: benign and malicious. Although they both induce negative feelings, the primary motivation in benign envy is to develop and evolve to reach the achievement of others or obtain the same possessions, whereas malicious envy is associated with the motivation to hurt or diminish others to make them lose their advantages [10, 11]. Schadenfreude is defined as a pleasant emotion elicited by the misfortunes of others [11], generally occurring when the others are “maliciously” envied or disliked [12, 13]. Importantly, experiencing these emotions increases the feeling of shame, inferiority, anger or resentment [10] and is negatively perceived by others [14]. Consequently, if AN-R patients are prone to experiencing these emotions, they may be subject to more negative affect and social isolation, thus risking maintaining or even worsening their symptomatology. Importantly, unlike other social deficits suffered by AN-R patients (e.g., decoding others’ mental states, cold attitude), experiencing these emotions may adversely impact both their intra- (e.g., self-esteem) and interpersonal functioning (e.g., being negatively perceived by others). Therefore, experiencing these emotions may be particularly deleterious for these patients, so this issue needs to be addressed.

The literature provides arguments in favor of this hypothesis. Indeed, higher experiences of Schadenfreude and malicious envy have been associated with narcissism, low self-esteem and high social comparison [10, 12, 15,16,17], which are frequently reported by AN-R patients and which predict low body satisfaction [18,19,20]. As a result, AN-R patients may experience higher Schadenfreude and malicious envy as a way to restore their low self-esteem. Specifically, individuals who experience a self-evaluation threat may experience more Schadenfreude due to their greater need to restore their self-worth [21, 22]. In support of our hypothesis, preliminary research has emphasized the role of envy in eating disorders [23,24,25]. For instance, a qualitative study showed that patients with AN report experiencing envy towards others [24]. It has also been shown that the rate of rejection of unfair offers in an ultimate game (i.e., suggested to reflect feelings of envy towards the other player) tended to be higher in AN patients (restrictive and binge-eating/purging subtypes combined) compared to healthy controls [25].

The main objective of the present study was to go beyond these preliminary findings and to test the hypothesis that AN-R patients experience greater malicious envy and greater Schadenfreude than healthy controls (HC). The investigation of the relationship between AN-R and benign envy was more explorative, so not associated with specific hypotheses. The second objective was to examine whether low reports of self-esteem and a strong tendency to compare oneself socially are related to the experience of these feelings in general and/or in the patient’s care (i.e., toward other inpatients). Finally, because the inclusion criteria for patients were based on DSM-5, which defines the severity of AN-R in terms of body mass index (BMI), we hypothesized that more severe AN-R (lower BMI) would be associated with higher reports of envy and Schadenfreude.

Method

Participants

Twenty-six female inpatients with restrictive anorexia nervosa (AN-R) were recruited in inpatient units at two psychiatric clinics (Clinique La Ramée, Brussels, Belgium; CHU Lille, France). The diagnoses were obtained from the patients’ medical records (derived from clinical interview) and were based on DSM-5 criteria [26]. Thirty-two healthy women were recruited in the social networks of the investigators and undergraduate students who collected the data. The inclusion criteria included normal weight (BMI 18.50–24.99 kg/m2) and no history of eating disorders, as assessed by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview [27]. Exclusion criteria for both groups included any major medical or neurological disorders, including those requiring medications, visual impairment, and substance use disorders.

Material

Scenarios We created four scenarios that aimed to induce envy and Schadenfreude in participants (see supplementary data). They were based on previous vignettes, the first part of which was intended to induce benign and malicious envy whereas the second part was intended to induce Schadenfreude [11, 12, 28]. In the present study, the scenarios included these two parts and described a person of the same age and sex (i.e., young adult female) to facilitate the participants’ tendency to project themselves on the characters. For instance, one of the four scenarios described a young female student who obtained a job thanks to familial support. After reading this first part, participants had to rate their experience of benign (“I would like to be in the position of (…)”, I would like to be in the shoes of (…)”) and malicious envy (“I’m jealous of (…); “I would like (…) to fail”) on a 6-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = totally disagree to 6 = totally agree) (adapted from [12]).Footnote 1 In the second part of each scenario that aimed at inducing Schadenfreude, the character had an unfortunate experience (e.g., being fired from her job). Participants were then instructed to rate the five usual Schadenfreude items on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 6 (totally agree) (“I’m satisfied with what happened to (…),” “I like what happened to (…),” “I couldn’t resist a little smile,” “I actually had to laugh a bit,” and “I felt Schadenfreude”; [29]). Internal consistency across the four scenarios was satisfactory (benign envy: α = .82; malicious envy: α = .68; Schadenfreude: α = .84).

Iowa-Netherlands Comparison Orientation Measure (INCOM French version, [30]) is an 11-item questionnaire that measures the tendency to compare oneself with others on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) (e.g., “I often compare myself with others with respect to what I have achieved in life”). Higher scores indicate higher social comparison. The English and Dutch versions present satisfactory internal consistency and test–retest reliability [31]. Its internal consistency in the present research was satisfactory (α = .81).

Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale (French version, [32]). Participants have to assess on a 4-point Likert scale (from totally disagree to totally agree) the extent to which they agree with 10 items related to their self-esteem (e.g., “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself”). Higher scores indicate higher self-esteem. The French version of the measure presents satisfactory internal consistency and test–retest reliability [32]. Its internal consistency in the present research was satisfactory (α = .68).

The Benign and Malicious Envy Scale (BeMaS [33]). The French version produced by the authors using a back-translation procedure is a 10-item scale that assesses the tendency of participants to experience benign and malicious envy. Participants rate on a 6-point Likert scale (from 1 = totally disagree to 6 = totally agree) the extent to which they agree with each item (e.g., benign envy: “When I envy others, I focus on how I can become equally successful in the future”; malicious envy: “I wish that superior people would lose their advantage”). The Dutch version of the measure presents satisfactory internal consistency [33]. Its internal consistency in the present research was also satisfactory (benign envy: α = .81; malicious envy: α = .86).

Envy towards inpatients Finally, we developed a 6-item questionnaire for AN-R inpatients that assesses benign (3 items; i.e., “I wanted to look the same as other patients”; “I wanted to do as well as other patients;” “I wanted to have the same characteristics/qualities as other patients”) and malicious envy (3 items; i.e., “I feel bad when other patients reach their goals”; “I wanted other patients not to have some qualities”; “I have a negative feeling towards patients whom I consider better than me”) they experienced during the last 2 weeks of their stay towards the other Eating Disorders inpatients (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, 5 = usually; 6 = always). It aimed to test whether envy towards inpatients also occurs in AN-R clinical care and whether it is related to social comparison and self-esteem. Its internal consistency was satisfactory (benign envy: α = .85; malicious envy: α = .71).

Procedure

Participants were tested individually. Once they had signed the consent form, they read the scenarios and completed the questionnaires. At the end, they were fully debriefed about the study. The study lasted 30 min and was approved by the local ethical committee (Comité d’Ethique Hospitalo-Facultaire Saint-Luc-UCL; Belgium).

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software package Version 24. Univariate analysis of variance was used to test the effect of the group on envy, Schadenfreude, self-esteem and social comparison. Pearson correlations investigated the association between variables.

Results

As presented in Table 1, AN-R patients did not significantly differ in age from HC but presented significantly lower BMI. Patients also reported lower self-esteem (medium effect size) and a greater tendency to compare themselves with others (large effect size).

Regarding our first objective, results revealed that the scenarios led AN-R patients to experience more benign envy than HC (medium effect size) with no significant difference regarding malicious envy and Schadenfreude. Furthermore, AN-R patients reported that they experienced benign envy “sometimes to often” (M = 3.54; SD = 1.14), but reported “no to rare” experience of malicious envy (M = 1.59 SD = .72) towards the other inpatients.

In respect to our second objective, Table 2 shows that social comparison was significantly correlated with two measures of benign envy (towards inpatients and BeMaS) and with malicious envy measured by the BeMaS. However, there was no significant correlation between self-esteem and envy or Schadenfreude.

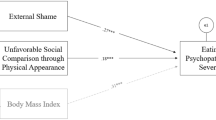

Finally, regarding the third objective, Table 3 shows that lower BMI was associated with higher reports of benign envy, malicious envy and Schadenfreude in the AN-R group only. Compared to HC, the correlations in AN-R patients tended to be significantly different for malicious envy (Z-score = 1.34; p < .10) and Schadenfreude (Z-score = 1.33; p < .10).

Discussion

The aim of the study was to test whether AN-R patients experience greater envy (malicious and benign), Schadenfreude, lower self-esteem and higher social comparison than healthy controls (HC). Moreover, we aimed to examine the associations between BMI and these variables in AN-R patients. Based on self-reported measures and scenarios, results showed that AN-R patients reported lower self-esteem, more social comparison, and experienced more benign envy than HC. Interestingly, lower BMI was associated with higher benign envy, malicious envy and Schadenfreude in AN-R only.

The significant finding about benign envy is in line with previous studies [23, 24] and shows that AN-R patients were more motivated to evolve and reach the status of others than HC. They also reported on average that they experienced benign envy towards the other patients ‘sometimes to often’, suggesting that their general tendency to experience this feeling is also present in the inpatient environment. Although benign envy refers to an unpleasant experience of frustration at not possessing what others have or having their quality, this may have positive effects for AN-R patients. It has been suggested that benign envy resolves this frustration by getting individuals to improve and surpass themselves by performing better [13, 33] and that it occurs when the outcome of the other person is perceived as positive and deserved [11]. Consequently, the presence of other inpatients may be beneficial if weaker symptomatology is perceived as positive and deserved, leading patients to wish to improve their own clinical status. On the contrary, an inpatient environment might lead to deleterious outcomes if AN-R patients perceive, compare and then acquire new problematic eating behaviours. Moreover, it has been shown that benign envy may have no impact if the goal is not reachable [34]. Specifically, higher reports of benign envy led participants to report more motivation to perform better only when they thought they could improve their performances as much as the others. Based on another study, one may even suggest the deleterious effect of benign envy if no self-affirmation opportunity is available [22]. In the latter study, participants with low self-esteem reported higher self-threat (e.g., feeling less good when comparing oneself with the other person) and subsequently higher Schadenfreude towards higher achievers (i.e., other students with high academic performances) when there was no opportunity for self-affirmation (i.e., no possibility to affirm one’s most important value) [22]. Based on these findings, one could thus recommend a balanced attitude in AN-R clinical care by encouraging the positive aspects of benign envy (e.g., surpassing oneself) while remaining particularly alert to the influence of other factors (e.g., opportunity for self-affirmation, reachable goals) and to the risk that benign envy turns into competition, which has been hypothesized to maintain AN-R disorders [35].

The non-significant group differences in malicious envy and Schadenfreude appear to be accounted for by the influence of a third variable, i.e. patients’ BMI, which significantly predicted envy and Schadenfreude. Indeed, despite the questionable role of BMI in defining AN-R severity [36, 37], higher BMI in AN-R patients was associated with feeling less envy (particularly malicious) and Schadenfreude. In other words, when faced with individuals who they perceived as having greater quality, patients with more severe AN-R (i.e., lower BMI) felt greater motivation to surpass themselves or to hurt them and experienced more pleasant emotion as a result of the misfortunes of those individuals. Because BMI was not correlated with self-esteem or social comparison, these psychological factors are likely not involved in this association, or at least not in a linear way. The association between self-esteem and BMI is thought to be moderated by AN recovery stage. For instance, self-esteem was negatively correlated with BMI in acute AN-R patients, whereas these variables were not associated with patients who had already recovered [38]. Therefore, weight gain in AN-R patients with low BMI may be experienced as a failure of the self or as a tendency to deviate from one’s objective, whereas it does not seem to have any deleterious effect in patients who have recovered. Therefore, self-esteem might not be associated with envy, Schadenfreude or BMI in all AN-R patients, due to the complex nature of self-esteem in AN-R. The association might be context-dependent, i.e. when there is no opportunity for self-affirmation, the misfortunes of others might be particularly pleasant for severe AN-R patients (i.e., low BMI) because they might protect or enhance their self-evaluation [21]. Of note, lower BMI may reduce AN patients’ cognitive ability to find new ways to face challenging situations (i.e., flexibility; problem-solving, [39, 40]). This may consequently lead patients to use Schadenfreude as a less cognitively demanding way to enhance their self-evaluation than strategies that require more cognitive resources such as reappraisal [41]. Therefore, although some studies have emphasized the social implications of BMI [42, 43], future studies should also consider other confounders when examining the links between AN-R and interpersonal functioning, i.e. AN-R current and lowest BMI, chronicity, stage of recovery and cognitive functioning.

Concerning the non-significant associations between malicious envy, Schadenfreude and social comparison in AN-R, future studies should focus on upward social comparison rather than the general tendency to compare oneself with others, as envy may result from upward social comparison [34]. This is particularly relevant in AN because upward appearance comparison has been shown to predict future eating disorders [44] and because ED patients reported higher levels of submissive behaviour and a more unfavourable social comparison (i.e., perceiving oneself as worse than someone else) than matched HC [45]. Therefore, unfavourable social comparison in ED patients may deteriorate social interactions perceived as potentially damaging in terms of self-devaluation [3]. If setting one’s own social and body standards higher (i.e., maladaptive perfectionism) were to be associated with difficulties in social comparison and hence social emotions, these high standards would translate into envy and Schadenfreude for those with lower BMI. Future studies could thus focus on the predictive role of upward social comparison and high standards for the self as factors accounting for impaired social interactions in AN-R. This may also account for the non-significant group differences in malicious envy and Schadenfreude that we found.

The study is not free from limitations. First, we cannot rule out the hypothesis of social desirability, especially for such socially unaccepted emotions. Future studies should thus add an implicit measure of Schadenfreude (e.g., recording facial expressions, see [46]) to counter this effect. A second limitation is that other comorbid diagnoses were not collected, so such confounders could not be excluded. Third, the AN-R group had greater benign envy than the control group for the scenarios measure but not for the BEMAS measure, probably due to low power. In addition, although the internal consistencies of all measures were satisfactory, the different measures of benign envy were not inter-correlated. Fourth, the sample size was small, preventing us from examining other research questions such as potential interactions between group (AN-R vs HC) and self-esteem in predicting the different forms of envy. Finally, other clinical data (i.e., frequency of restriction behaviours) should be collected in further studies. Nevertheless, despite these limitations, the study has several strengths including that it is the first to investigate whether AN-R patients are prone to experiencing negative emotions related to the misfortune of others based on three complementary measures. Finally, the study highlighted the significant role of BMI in AN-R patients’ social functioning.

Notes

Participants had to rate the four items from [12] (“I would like to be in the position of (…)”, “I’m jealous of (…),” “I would like to be in the shoes of (…)”, and “I feel less good when I compare my own results with those of (…)”) and one additional item designed to explicitly measure malicious envy (“I would like (…) to fail”). According to a factorial analysis on the whole sample (Promax rotation), four out of the five items presented factor loadings > .40 on either one out of two factors, namely benign (2 items; “I would like to be in the position of (…)”, “I would like to be in the shoes of (…)”) and malicious envy (2 items; I’m jealous of (…),” I would like (…) to fail”).

References

Ambwani S, Berenson KR, Simms L et al (2016) Seeing things differently: an experimental investigation of social cognition and interpersonal behavior in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 49:499–506. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22498

Oldershaw A, Hambrook D, Stahl D et al (2011) The socio-emotional processing stream in anorexia nervosa. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35:970–988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.11.001

Schmidt U, Treasure J (2006) Anorexia nervosa: valued and visible. A cognitive-interpersonal maintenance model and its implications for research and practice. Br J Clin Psychol 45:343–366

Treasure J, Schmidt U (2013) The cognitive-interpersonal maintenance model of anorexia nervosa revisited: a summary of the evidence for cognitive, socio-emotional and interpersonal predisposing and perpetuating factors. J Eat Disord 1:13. https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-2974-1-13

Caglar-Nazali HP, Corfield F, Cardi V et al (2014) A systematic review and meta-analysis of ‘Systems for Social Processes’ in eating disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 42:55–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.12.002

Nandrino J-L, Ducro C, Iachini T, Coello Y (2017) Perception of peripersonal and interpersonal space in patients with restrictive-type anorexia. Eur Eat Disord Rev J Eat Disord Assoc 25:179–187. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2506

Tchanturia K, Davies H, Harrison A et al (2012) Altered social hedonic processing in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 45:962–969. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22032

Jankowski KF, Takahashi H (2014) Cognitive neuroscience of social emotions and implications for psychopathology: examining embarrassment, guilt, envy, and schadenfreude. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 68:319–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12182

Parrott WG, Smith RH (1993) Distinguishing the experiences of envy and jealousy. J Pers Soc Psychol 64:906–920

Crusius J, Mussweiler T (2012) When people want what others have: the impulsive side of envious desire. Emot Wash DC 12:142–153. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023523

van de Ven N, Zeelenberg M, Pieters R (2012) Appraisal patterns of envy and related emotions. Motiv Emot 36:195–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-011-9235-8

van Dijk Ouwerkerk JW, Goslinga S et al (2006) When people fall from grace: reconsidering the role of envy in Schadenfreude. Emot Wash DC 6:156–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.6.1.156

van de Ven N, Hoogland CE, Smith RH et al (2015) When envy leads to schadenfreude. Cogn Emot 29:1007–1025. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2014.961903

Jung K, Karasawa K (2016) How we view people who feel joy in our misfortune. Korean J Soc Pers Psychol 30:41–61

van de Ven N (2017) Envy and admiration: emotion and motivation following upward social comparison. Cogn Emot 31:193–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2015.1087972

Vrabel JK, Zeigler-Hill V, Southard AC (2018) Self-esteem and envy: is state self-esteem instability associated with the benign and malicious forms of envy? Pers Individ Differ 123:100–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.11.001

Lange J, Crusius J, Hagemeyer B (2019) The Evil Queen’s dilemma: linking narcissistic admiration and rivalry to benign and malicious envy. Eur J Pers Banner. 1:1. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/zs7mc

Connan F, Troop N, Landau S et al (2007) Poor social comparison and the tendency to submissive behavior in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 40:733–739. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20427

Doba K, Nandrino J-L, Dodin V, Antoine P (2014) Is there a family profile of addictive behaviors? Family functioning in anorexia nervosa and drug dependence disorder. J Clin Psychol 70:107–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21977

Myers TA, Crowther JH (2009) Social comparison as a predictor of body dissatisfaction: a meta-analytic review. J Abnorm Psychol 118:683–698. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016763

van Dijk Ouwerkerk JW, Wesseling YM, van Koningsbruggen GM (2011) Towards understanding pleasure at the misfortunes of others: the impact of self-evaluation threat on schadenfreude. Cogn Emot 25:360–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2010.487365

van Dijk A, van Koningsbruggen GM, Ouwerkerk JW, Wesseling YM (2011) Self-esteem, self-affirmation, and schadenfreude. Emot Wash DC 11:1445–1449. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026331

Jin SV (2018) Interactive effects of Instagram Foodies’ Hashtagged #Foodporn and Peer Users’ eating disorder on eating intention, envy, parasocial interaction, and online friendship. Cyberpsychology Behav Soc Netw 21:157–167. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0476

Skårderud F (2007) Shame and pride in anorexia nervosa: a qualitative descriptive study. Eur Eat Disord Rev J Eat Disord Assoc 15:81–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.774

Isobe M, Kawabata M, Murao E et al (2018) Exaggerated envy and guilt measured by economic games in Japanese women with anorexia nervosa. Biopsychosoc Med 12:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13030-018-0138-8

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Association, New York

Lecrubier Y, Sheehan D, Weiller E et al (1997) The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur Psychiatry 12:224–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83296-8

Porter S, Bhanwer A, Woodworth M, Black PJ (2014) Soldiers of misfortune: an examination of the Dark Triad and the experience of schadenfreude. Pers Individ Differ 67:64–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.11.014

van Dijk Goslinga S, Ouwerkerk JW (2008) Impact of responsibility for a misfortune on schadenfreude and sympathy: further evidence. J Soc Psychol 148:631–636. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.148.5.631-636

Michinov E, Michinov N (2001) The similarity hypothesis: a test of the moderating role of social comparison orientation. Eur J Soc Psychol 31:549–555

Gibbons FX, Buunk BP (1999) Individual differences in social comparison: development of a scale of social comparison orientation. J Pers Soc Psychol 76:129–142

Vallières EF, Vallerand RJ (1990) Traduction et validation Canadienne-Française de l’Échelle de l’Estime de Soi de Rosenberg. [French-Canadian translation and validation of Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale.]. Int J Psychol 25:305–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207599008247865

Lange J, Crusius J (2015) Dispositional envy revisited: unraveling the motivational dynamics of benign and malicious envy. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 41:284–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214564959

van de Ven N, Zeelenberg M, Pieters R (2011) Why envy outperforms admiration. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 37:784–795. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211400421

Treasure J, Crane A, McKnight R et al (2011) First do no harm: iatrogenic maintaining factors in anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev J Eat Disord Assoc 19:296–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1056

Brown TA, Holland LA, Keel PK (2014) Comparing operational definitions of DSM-5 anorexia nervosa for research contexts. Int J Eat Disord 47:76–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22184

Reas DL, Rø Ø (2017) Investigating the DSM-5 severity specifiers based on thinness for adults with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 50:990–994. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22729

Brockmeyer T, Holtforth MG, Bents H et al (2013) The thinner the better: self-esteem and low body weight in anorexia nervosa. Clin Psychol Psychother 20:394–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1771

Paterson G, Power K, Yellowlees A et al (2007) The relationship between two-dimensional self-esteem and problem solving style in an anorexic inpatient sample. Eur Eat Disord Rev 15:70–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.708

Tchanturia K, Harrison A, Davies H et al (2011) Cognitive flexibility and clinical severity in eating disorders. PLoS ONE 6:e20462. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020462

Ortner CNM, Marie MS, Corno D (2016) Cognitive costs of reappraisal depend on both emotional stimulus intensity and individual differences in habitual reappraisal. PLoS ONE 11:e0167253. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167253

Duclos J, Dorard G, Berthoz S et al (2014) Expressed emotion in anorexia nervosa: what is inside the “black box”? Compr Psychiatry 55:71–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.10.002

Toman E (2002) Body mass index and its impact on the therapeutic alliance in the work with eating disorder patients. Eur Eat Disord Rev 10:168–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.458

Arigo D, Schumacher L, Martin LM (2014) Upward appearance comparison and the development of eating pathology in college women. Int J Eat Disord 47:467–470. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22240

Troop NA, Allan S, Treasure JL, Katzman M (2003) Social comparison and submissive behaviour in eating disorder patients. Psychol Psychother 76:237–249. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608303322362479

Cikara M, Fiske ST (2013) Their pain, our pleasure: stereotype content and schadenfreude. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1299:52–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12179

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional board and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grynberg, D., Nandrino, JL., Vermeulen, N. et al. Schadenfreude, malicious and benign envy are associated with low body mass index in restrictive-type anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord 25, 1071–1078 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00731-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00731-7