Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this narrative review of the literature was to evaluate and summarize the current literature regarding the effect of lipedema on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and psychological status.

Methods

The authors collected articles through a search into Medline, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro), and the Cochrane Review. Search terms used included “Lipoedema,” “Lipedema,” “psychological status,” “Quality of life,” “Health related quality of life,” and “HRQOL.”

Results

A total of four observational studies were evaluated. The included studies were moderate-quality according to the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. Three of the included studies demonstrated deterioration of HRQOL and psychological status in patients with lipedema. These studies also identify that pain and tenderness are a more common and dominant characteristic.

Conclusion

Future studies should establish a specific approach to treat and manage lipedema symptoms. Based on this narrative review of the literature findings, we recommended for the health care provider to pay more attention to HRQOL and psychological status. Moreover, validated and adapted measures of HRQOL and psychological status for patients with lipedema are required.

Level of evidence

Level V, narrative review.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Lipedema is a chronic and progressive disease of adipose tissue characterized by abnormal subcutaneous fat deposition, leading to swelling and enlargement of the only lower limbs [1, 2]. It is often misdiagnosed as lymphoedema or obesity, because lipedema may coexist with obesity [2, 3]. Patients with lipedema showed a higher body mass index (BMI), but BMI may be inaccurate to reflect the index of adiposity because it does not measure body fat and poorly distinguishes fat from lean or bone mass [4,5,6]. The etiopathogenesis of lipedemais is not fully understood, but a number of different causes have been proposed [4, 7,8,9]. These causes are emphasized on either genetic inheritance or hormonal changes [4, 7,8,9]. Genetic background with familial predisposition has been described in 60% of lipedema cases [7]. Moreover, the inheritance of X-linked dominant or autosomal dominant pattern with sex limitation may contribute too [4]. The hormone-related disease mainly affects women starting puberty, after pregnancy or during menopause [4, 8]. Estrogen contributes to decreased lipolysis in the gluteal, compared with the abdominal region due to a distinct pattern of estrogen receptors [9].

Lipedema can be classified into three clinical stages based on morphological appearance. Stage 1, the skin is smooth with an enlarged and nodular sub-dermis; stage 2, larger masses form, and bands of peri-lobular fascia thicken and contract, pulling the skin down in a mattress pattern. In stage 3, the skin thins and loses elasticity allowing adipose tissues to grow in excess and fold over inhibiting flow. Five types of lipedema manifestations have been identified by Schingale: type I, adipose tissue increased on buttocks and thighs; type II, the lipedema extends to the knees with formation of fat pads on the inner side of the knees; type III lipedema extends from the hips to the ankles; type IV involving the arms and legs; type V, lipo-lymphedema [10]. Patients with lipedema reported deterioration in their quality of life (QoL) and abnormal psychological status during these stages [1, 2, 4, 7]. In fact, there are many factors contributing to this deterioration. First, the lack of a clear diagnosis and management of this disabling disease [11]. Second, the severe complications of lipedema such as: reduced joint mobility, severe pain, hematoma, edema and insufficient lymphatic backflow [1, 2]. Third, the non-significant improvement of some approaches used to treat those patients such as diet and exercise [11, 12]. Moreover, people with lipedema are feeling rejected by medical personnel, because they are stigmatized as being obese [2]. This weight stigma and uncontrollable changes in body appearance over time will lead to learned helplessness, self-stigmatization, depression, anxiety, stress, feelings of shame and guilt, and body dissatisfaction [11,12,13,14]. In addition to the psychological and medical complications of lipedema mentioned above, these factors can increase the risk of depression, anxiety and eating disorders that further affect the QoL and the activity of daily living in people with lipedema [12, 15].

Therefore, lipedema can influence negatively the patients’ lives, especially the health-related quality of life (HRQOL). For the World Health Organization (WHO) the HRQOL is “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value system in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns” [16]. In fact, the health well-being is in the middle of a complex relationship among the physical and psychological condition, the social interrelation, the personal dogma and the work or house environment. Since, many studies were conducted to confirm the lipedema diagnosis, and/or to investigate the effectiveness of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions on people with lipedema. However, to our knowledge, no narrative review of the literature investigates the effect of lipedema on HRQOL and/or psychological status in people with lipedema. Therefore, the objective of this narrative review is to evaluate, summarize and discuss the available literature concerning HRQOL and psychological status in patients with lipedema.

Methods

The authors collected articles through a search into Medline, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro), and the Cochrane Review were used. The search terms used included “Lipoedema,” “Lipedema,” “psychological status,” “Quality of life,” “Health related quality of life” and “HRQOL”. In addition, the works included in the bibliographies of the selected articles have also been taken into consideration. Observational studies that investigated the effects of lipedema on HRQOL and/or psychological status were included. On the contrary, studies evaluating the HRQOL and/or psychological status after intervention such as exercises, diet and liposuction surgeries [17,18,19,20], and studies not in English, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and pilot studies were excluded.

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to evaluate the quality of each included study [21] and this includes eight assessment items for quality appraisal including ‘selection’, ‘comparability’ and ‘outcome’. According to the NOS score standard, cross-sectional studies could be classified as low-quality (scores of 0–4), moderate-quality (scores of 5–6) and high-quality (scores ≥ 7).

Results

Four observational cross-sectional studies relevant to the aim of this review were selected (Table 1) [22,23,24,25]. The four included studies showed moderate quality according to NOS scores (Table 2). The level of evidence for the included studies was at level V, narrative review.

Health-related quality of life measures

Different instruments to measure the HRQOL in the included studies were used. The World Health Organization Quality of Life scale (WHOQOL-BREF) was used in 2 studies [22, 24]. The other two studies used RAND-36 and EQ-5D-3L to determine HRQOL [23, 25]. Three studies used only online questionnaires [22,23,24]; one study conducted face-to-face interview by medical doctor students [25]. In addition to HRQOL, all included studies reported on other psychological and social constructs, such as social support and personality structure. However, these instruments were beyond the scope of this review.

WHOQOL-BREF includes a 26-items and split in four domains of 5-point scale, to investigate psychologic state, physical well-being, social relationship and surroundings. In addition to the four domains, WHPQOL-BREF includes two individual scored items to assess rated QoL and health. The study of internal coherence, discrimination, construction and convergent validity indicate that WHOQOL-BREF is in agreement to QoL assessment. Consequentially, a high score points out a good QoL [16]. RAND-36 is a survey instrument which provides information on how health impacts an individual’s skill and person’s perceived well-being [26]. RAND-36 comprised of 36 element that assess nine health scale: health status realization, functional reserve, psychical health, pain, work problems due to disability and to mood condition, life power, health and social deterioration [27]. EQ-5D-3L is a useful tool to assess the HRQOL. It includes five scale (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression). These dimensions were measured on a three-point scale: 0, no problems; 1, some or moderate problems; 2, extreme problems [28, 29].

Effect of lipedema on Health-related quality of life and Psychological status

To gain insight into the depth and complexity of the problems experienced by women with lipedema and to explore the possible impact of psychological factors, Dudek et al. [22] evaluated the impact of psychological factors on HRQOL of women with lipedema. They conducted an internet-based cross-sectional study. One-hundred and twenty women from different countries with lipedema participated. They found that participants with higher levels of symptoms severity reported lower HRQOL. In addition, they observed that the higher levels of psychological flexibility and social connectedness are connected with higher levels of HRQOL. Dubek noted that pain and tenderness were extremely severe in 50% of the participants [22].

In a study 3 years later, the same author Dudek et al. [24] assessed the role of perceived symptoms severity, physical and psychological functioning with the disease in predicting HRQOL in patients with lipedema. Each participant was asked to complete an online study which included HRQOL, lipedema symptoms severity, mobility, depression, and appearance-related distress. Three-hundred and twenty-nine participants completed the online study, located in different places around the world. HRQOL was inversely correlated with lipedema symptoms severity, depression severity and level of appearance related distress respectively (− 0.651; − 0.750; − 0.654). Furthermore, higher mobility correlated positively with HRQOL (r = 0.607) [24].

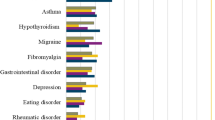

Another study conducted by Romeijn et al. [23] sent a survey by email to evaluate the patient’s characteristics, HRQOL, physical complaints and comorbidities. The study evaluated 163 patients with lipedema, HRQOL was determined by 2 instruments. The EQ-5D questionnaires total scores were lower compeered to general Dutch female population (66.1 and 85 respectively). Additionally, the RAND-36 scores were lower than the mean Dutch female RAND-36 score (59.3 and 74.9 respectively). Moreover, they observed that the comorbidities were 56.4% of the participants and had significantly lower HRQOL (RAND 54.7, p = 0.001; EQ-5D 60.5, p = 0.001) compared with those with no comorbidities (RAND 73.2; EQ-5D 65.0). They also found that patients with comorbidities had BMI of 36.6 compared with 29.7 kg/m2 in patients without comorbidities. Moreover, 63.0% of the participants had some problems with mobility, although none reported being confined to bed. Only 9.9% reported some problems with washing or dressing, and1.2% were unable to wash or dress. Anxiety or depression was mentioned in 42.0%, with 1.2% reporting to be extremely anxious or depressed [23].

Only one published example of the development of a disease-specific tool to evaluate HRQOL for patients suffering from lipedema was identified. In 2013, Blome et al. [25] published their results of the development and validation of a tool, the patient benefit index (PBI), to assess the benefit in lymphedema and lipedema treatment. The PBI was validated in a sample of 301 patients. Of these 301 patients 33.6% (n = 101) had lipedema or lipolymphedema. Data were gathered from a number of sources. Generic HRQOL scales completed from patient interviews, EQ-5D-3L scale completed by the patients and the overall opinion of doctors and patients. The result demonstrated a very low and non-significant correlation between generic HRQOL (EQ-5D-3L) and PBI scores (r = − 0.01 to − 0.09) [25].

Discussion

The aim of this narrative review was to evaluate the effects of lipedema on HRQOL and psychological status in patients with lipedema. This review included articles that study the effect of lipedema on HRQOL and psychological status. The search strategy found four observational cross-sectional studies. The results of the included articles found that the HRQOL and psychological status decreased and deteriorated in patients with lipedema. The evidence from the included studies using generic tools to assess HRQOL and psychological status is that patients with lipedema have a poorer psychological adjustment, greater deficits in their ability to function physically and socially and increased anxiety and depression. These studies also identify that pain and tenderness are more common and dominant symptoms. These findings indicate that pain, poor skin condition, and reduced limb mobility are factors that can lead to deficits in HRQOL.

The studies reviewed in this article are representative of a growing trend towards efforts to understand how lipedema affects the lives of patients. However, despite the predominately negative effects of lipedema noted, the quality of evidence of current literature remains moderate. The included studies were observational cross-sectional studies with a diversity of methodologies and different tools used to evaluate QoL.

Currently, the mutual influence between the perception of symptoms, such as pain, and the psychological condition is well known. Both factors affect the psychophysical homeostasis of patients by requiring a greater adaptive effort and worsening the state of the subject [30]. Hence, an appropriate psychological path is necessary to increase stress resilience, mood quality and symptom perception. Overall, this could improve the patient's HRQOL. In fact, as reported by Romeijn et al. the worsening of HRQOL is evident in obese subjects with comorbidity, in particular, depression and anxiety. Previous research has suggested that excess weight affects the subjective perception of QoL, but it is not enough to explain this affection. Therefore, obesity, specific clinical manifestations of fat disorders, functional limitations and psychological status contribute to the expiry of HRQOL [31]. In the field of fat disorders, few studies investigated the relationship between QoL, physical and psychological functioning.

In addition to clinical evaluation and mood status, the possible diagnosis of secondary Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) should not be overlooked. Indeed, we hypothesize that the acceptance difficulty of the pathology and the bodily deformations, brings out an eating behavior that complicates the basic pathology leading to obesity.

The numerous health figures that interface with the multidisciplinary therapeutic path of the patient suffering from fat disorders must know and overcome the stigma and shaming of fat. First, patients with lipedema are not primarily obese. Second, the generalization and stigma of fat, in addition to humiliating patients, provide an excuse of treatment failure [32]. By studying the tools for the overall evaluation of lipedema treatments, Blome et al. demonstrated the need for a multi-scale multi-parameter instrument, the PBI. This evaluates the general state of the patient and the specific symptoms and signs of illness, satisfaction and mood, both retrospectively and longitudinally. The complexity of the PBI expresses the stratification of comorbidities afflicting women with lipedema and other fat disorders.

Our narrative review has several connections with the clinical problems. It focuses on the need for clear and timely information to help patients and caregivers. Also, it is brought to light the necessity to find a comprehensive definition of lipedema to correctly evaluate and treat the disease. Thus, psychological conditions and clinical symptoms (especially the evaluation of pain and skin involvement) should be fully assessed.

Conclusion

Lipedema is a chronic, complex and multifaceted condition that has major physical, psychological and social implications for the HRQOL of patients. The main aim of treatment and management is to improve and/or maintain HRQOL and psychological status.

Mounting evidence clarifies the correlation between the perception of symptoms and the psychological condition in patients with lipedema. Indeed, it has been shown that excess weight negatively affects the subjective perception of the quality of life and that this is not enough to explain the decay, but the comorbidities associated with the condition of obesity determine the decay of the indices of measure of quality of life (HRQOL). Therefore, a targeted psychological path arises as an essential action of the treatment path, also considering the possible secondary diagnosis of fed that could emerge.

However, despite the negative effects of lipedema on HRQOL and psychological status, the quality of evidence of the current literature remains low. The studies were predominantly cross sectional studies and the remaining varied in size and outcome measures; therefore, it was not possible to compare and poor data for formal meta-analysis. Moreover, the included studies in this narrative review assessed both HRQOL and physiological status by different way, mainly they used the online questionnaire. Nevertheless, despite these limitations, the reported studies showed some encouraging findings that would deserve to be investigated by means of larger randomized controlled trials with more specific outcomes measures.

To achieve this goal, the evidence from this review highlights the importance of having in place a specific approach to treat and manage that includes patient support. A comprehensive education program for health care workers within an integrated and evidence-based medicine must support this approach. Clearly, the HRQOL and psychological status of patients with lipedema must be a key element when evaluating the success of such approaches in the future.

References

Fonder MA, Loveless JW, Lazarus GS (2007) Lipedema, a frequently unrecognized problem. J Am Acad Dermatol 57:S1–S3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2006.09.023

Forner-Cordero I, Szolnoky G, Forner-Cordero A, Kemény L (2012) Lipedema: an overview of its clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment of the disproportional fatty deposition syndrome—systematic review. Clin obes 2:86–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-8111.2012.00045.x

Schmeller W, Meier-Vollrath I (2005) Lipödem: Ein update. LymphForsch 9:10–20

Child AH, Gordon KD, Sharpe P, Brice G, Ostergaard P, Jeffery S, Mortimer PS (2010) Lipedema: an inherited condition. Am J Med Genet A 152:970–976. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.33313

De Lorenzo A, Soldati L, Sarlo F, Calvani M, Di Lorenzo N, Di Renzo L (2016) New obesity classification criteria as a tool for bariatric surgery indication. World J Gastroenterol 22:681. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i2.681

De Lorenzo A, Nardi A, Iacopino L, Domino E, Murdolo G, Gavrila C, Minella D, Scapagnini G, Di Renzo L (2014) A new predictive equation for evaluating women body fat percentage and obesity-related cardiovascular disease risk. J Endocrinol Investig 37:511–524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-017-0806-8

Fife CE, Maus EA, Carter MJ (2010) Lipedema: a frequently misdiagnosed and misunderstood fatty deposition syndrome. Adv Skin Wound Care 23:81–92. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ASW.0000363503.92360.91

Mayes JS, Watson GH (2004) Direct effects of sex steroid hormones on adipose tissues and obesity. Obes Rev 5:197–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00152.x

Gavin KM, Cooper EE, Hickner RC (2013) Estrogen receptor protein content is different in abdominal than gluteal subcutaneous adipose tissue of overweight-to-obese premenopausal women. Metabolism 62:1180–1188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2013.02.010

Schingale FJ (2003) Lymphoedema lipoedema. Schlütersche GmbH, Hannover, pp 20–21

Fife CE, Maus EA, Carter MJ (2010) Lipedema: a frequently misdiagnosed and misunderstood fatty deposition syndrome. Adv Skin Wound Care 23:81–92. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ASW.0000363503.92360.91

Herbst KL (2012) Rare adipose disorders (RADs) masquerading as obesity. Acta Pharmacol Sin 33:155. https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2011.153

Langendoen SI, Habbema L, Nijsten TEC, Neumann HAM (2009) Lipoedema: from clinical presentation to therapy. A review of the literature. Br J Dermatol 161:980–986. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09413.x

Seo CA (2014) You mean it's not my fault learning about lipedema a fat disorder. Narrat Inq Bioeth 4:E6–E9. https://doi.org/10.1353/nib.2014.0045

Bosman J (2011) Lipoedema poor knowledge neglect or disinterest? J Lymphoedema 6:109–111

Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O'Connell K (2004) The World Health Organization's WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res 13:299–310. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00

Dadras M, Mallinger PJ, Corterier CC, Theodosiadi S, Ghods M (2017) Liposuction in the treatment of lipedema a longitudinal study. Arch Plast Surg 44:324. https://doi.org/10.5999/aps.2017.44.4.324

Schmeller W, Meier-Vollrath I (2006) Tumescent liposuction a new and successful therapy for lipedema. J Cutan Med Surg 10:7–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/7140.2006.00006

Schneider R (2018) Low-frequency vibrotherapy considerably improves the effectiveness of manual lymphatic drainage (MLD) in patients with lipedema: a two-armed randomized controlled pragmatic trial. Physiother Theory Pract. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2018.1479474

Rapprich S, Dingler A, Podda M (2011) Liposuction: is an effective treatment for lipedema—results of a study with 25 patients. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 9:33–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1610-0387.2010.07504.x

Wells G (2004) The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analysis. https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology.oxford.htm. Accessed 6 Mar 2019

Dudek JE, Białaszek W, Ostaszewski P (2016) Quality of life in women with lipoedema: a contextual behavioral approach. Qual Life Res 25:401–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1080-x

Romeijn JR, de Rooij MJ, Janssen L, Martens H (2018) Exploration of patient characteristics and quality of life in patients with lipoedema using a survey. Dermatol Ther 1:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-018-0241-6

Dudek JE, Białaszek W, Ostaszewski P, Smidt T (2018) Depression and appearance-related distress in functioning with lipedema. Psychol Health Med 23:846–853. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2018.1459750

Blome C, Augustin M, Heyer K, Knöfel J, Cornelsen H, Purwins S, Herberger K (2014) Evaluation of patient-relevant outcomes of lymphedema and lipedema treatment: development and validation of a new benefit tool. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 47:100–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2013.10.009

Hays RD, Morales LS (2001) The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Ann Med 33:350–357. https://doi.org/10.3109/07853890109002089

Hays RD, Morales LS (2001) The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Ann Med 33:350–357

GroupTE (1990) EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 16:199–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9

Whoqol Group (1995) The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med 41:1403–1409. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-K

Abdallah CG, Geha P (2017) Chronic pain and chronic stress: two sides of the same coin? Chronic Stress. https://doi.org/10.1177/2470547017704763

Petroni ML, Villanova N, Avagnina S, Fusco MA, Fatati G, Compare A, QUOVADIS Study Group (2007) Psychological distress in morbid obesity in relation to weight history. Obes Surg 17:391–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-007-9069-3

Nath R (2019) The injustice of fat stigma. Bioethics. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12560

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alwardat, N., Di Renzo, L., Alwardat, M. et al. The effect of lipedema on health-related quality of life and psychological status: a narrative review of the literature. Eat Weight Disord 25, 851–856 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00703-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00703-x