Abstract

Purpose

To examine the psychometric properties and the factorial structure of the Italian version of the schema mode inventory for eating disorders—short form (SMI-ED-SF) for adults with dysfunctional eating patterns.

Methods

649 participants (72.1% females) completed the 64-item Italian version of the SMI-ED-SF and the eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q) for measuring eating disorder symptoms. Psychometric testing included confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and internal consistency. Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was also run to test statistical differences between the EDE-Q subscales on the SMI-ED-SF modes, while controlling for possible confounding variables.

Results

Factorial analysis confirmed the 16-factors structure for the SMI-ED-SF [S–Bχ2 (1832) = 3324.799; p < .001; RMSEA = 0.045; 90% CI 0.043–0.048; CFI = 0.880; SRMR = 0.066; χ2/df = 1.81; < 3]. Internal consistency was acceptable in all scales, with Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients ranging from 0.635 to 0.873.

Conclusions

The SMI-ED-SF represents a reliable and valid alternative to the long-form SMI-ED for assessment and conceptualization of schema modes in Italian adults with disordered eating habits. Its use is recommended for clinical and research purposes.

Level of evidence

Level V, descriptive study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) are serious and difficult-to-treat mental illnesses, often showing ego-syntonic features and resistance to treatments. Epidemiological studies usually underestimate the occurrence of EDs in the general population, since individuals are rarely aware of their illness and only occasionally refer to mental health care [1]. Many factors conspire to impede the treatment of EDs, including entrenched thinking, ambivalence about change, avoidant and perfectionistic personality traits, and comorbidity of trauma symptoms [2, 3].

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is widely recognized as the treatment of choice for adults with EDs [4]. Despite the widespread support for its efficacy [5, 6], therapy is often hampered by the well-known phenomenon of dropout [5].

Schema therapy (ST) is an integrative and multi-modal approach developed to address deeper levels of cognition and entrenched behaviours that do not respond to first-line treatments [7].

The goal of the ST treatment for EDs is to enable core psychological (and physiological) needs to be met [8], and to bring about change in eating habits by breaking enduring and self-defeating patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving that typically begin early in life as a result of the interaction between temperament and unmet core emotional needs—referred to as early maladaptive schemas (EMS)—whilst developing healthy coping mechanisms [9, 10]. Indeed, research, suggests that those who suffer from EDs experience significantly higher levels of maladaptive modes than community samples [11, 12]. The ST treatment for EDs includes recognizing and challenging Internalized Critic Modes, re-parenting to heal the vulnerable child mode, and bypassing the resulting coping modes that are linked to the over-evaluation of shape, weight, and self-starvation. Limits are also set on Angry and Impulsive Child Modes that drive a self-destructive “acting out” of needs (i.e., bingeing). Cognitive and behavioural techniques are considered core aspects of ST, but the model gives equal weight to emotion-focused work and experiential techniques, in addition to the basic healing components of the therapeutic relationship. As with CBT, ST is structured, systematic and specific, following a sequence of assessment and treatment procedures. However, the pace and emphasis on aspects of treatment may vary depending on the individual needs.

To facilitate more precise measurement of mode states within the ED population, the schema mode inventory for eating disorders (SMI-ED) was recently developed, showing adequate validity and reliability [13]. Given the large number of items in the SMI-ED (n = 190)—which make it cumbersome for everyday clinical practice—the purpose of the present study was to develop a shortened Italian version of the SMI-ED, to assess its psychometric proprieties, and to determine the internal reliability of its subscales. The relationship between ED symptoms (restraint, binge eating and purging) and schema modes was also explored.

Materials and methods

Participants

The sample comprised 649 participants [181 males (27.9%) and 468 females (72.1%)] aged from 18 to 91 years (mean = 40.66, SD = 18.27). The study was open to individuals (1) aged over 18 years old, (2) who were Italian-speaking and that (3) signed digital informed consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included the inability to complete the questionnaire due to visual or cognitive impairments. Participation was voluntary, and respondents did not receive remuneration.

Sample size calculation

Sample size calculation was based on two recommendations: first, that 500 or more observations can be considered “very good” for conducting a confirmatory factor analyses [14]; second, using the rule of ten subjects per item [15].

Measures

Demographics Information including age, gender, education, relationships, and employment status were collected.

Biomedical data Data on height and weight were registered and BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). Participants were also asked to report on the presence of existing diagnosis of eating disorders through a multiple choice question (“Have you ever been diagnosed with one of the following eating disorder?”) [16].

The Italian version of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) [17] The EDE-Q 6.0 is a 28-item self-report measure of ED attitudes psychopathology and behaviours in both community and clinical populations. The questions concern the frequency of key behavioural features of EDs in which the person engages over the preceding 28 days. The questionnaire is scored on a 7-point Likert scale (0–6), rated using four subscales (restraint—R; eating concern—EC; shape concern—SC; and weight concern—WC) and a global score.

The EDE-Q has generally received support as an adequately reliable and valid measure of eating-related pathology [13]. Similarly, in the present sample, the dimensions of the EDE-Q have demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (R-α = 0.804; EC-α = 0.822; SC-α = 0.900; WC-α = 0.800; General/Total-α = 0.944).

The Italian version of schema mode inventory for eating disorders—short form (SMI-ED-SF) The item-pool (n = 64) for the new SMI-ED-SF was first created independently by two clinicians/researchers specialized both in ST and in the treatment of ED (authors GP and SS), who listed the items under each of the 16 modes in order of relevance in observance of the ST conceptualization for EDs.

Simultaneously, and blinded from the other authors, a third researcher (not specialized in ST; author AR) identified those items showing higher factor loading for each dimension of the original SMI-ED [13]. Conclusions from the authors were matched and discussed until agreement on the final set of items for the SMI-ED-SF was reached. Four items (three general, and one EDs-specific statement—where applicable) per mode were retained—thus to overcome the limitation of the previous version of the tool—where the number of items was highly heterogeneous between modes.

The SMI-ED is a 190-item self-report questionnaire with sixteen different modes clustered thematically: (A) five innate child modes (1. vulnerable child—VC, 2. angry child—AC, 3. enraged child—EC, 4. impulsive child—IC and 5. undisciplined child—UC); (B) two maladaptive (internalized/introject) modes (6. punitive mode—PM and 7. demanding mode—DM); (C) seven maladaptive coping modes (8. compliant surrenderer—CS, 9. helpless surrenderer—DS, 10. detached protector—Det.P, 11. detached self-soother—Det.SS, 12. self-aggrandizer—SA, 13. bully and attack—BA 14. eating disorder overcontroller—EDO); and (D) two healthy factors (15. happy child—HC and 16. healthy adult—HA). Notably, two modes (IC and EC) only included items retrieved from the original version of the SMI [18], while the HS and the EDO modes exclusively consisted of new ED-specific statements.

The SMI-ED revealed acceptable internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.807 (Det.SS) to 0.976 (PM) across subscales (meanα-factors = 0.914; SDα-factors = 0.048).

Contrary to its full-length version—in which the number of items between scales varies from 5 (DS) to 20 (VC)—a fixed list of four statements was ensured for each of the SMI-ED-SF subscales (n = 16). Specifically, except for those modes only including either items retrieved from the original SMI or consisting of EDs-specific statements, the remaining subscales comprised three general statements and one item representative of the ED population.

Consistent with the previous versions of the tool [13, 18], items were scored on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“never or hardly ever”) to 5 (“all of the time”) and the score for each mode was computed dividing the sum scores by the number of items in each subscale. The higher the score, the more frequent were the manifestations of the modes.

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation

The SMI-ED-SF was independently translated from the original English version into Italian by two bilingual experts in the field, with one of them also having good knowledge of the measure. Any inconsistencies were revised and adjusted by a third investigator independent from the study using culturally and clinically fitting expressions. Also, to ensure conceptual equivalence between translations, a blind back translation of the Italian version of the SMI-ED-SF into English was conducted by an independent bilingual translator. Prior to the main study, the approved Italian version of the questionnaire was trialed with a random sample of 15 patients with EDs and 23 non-clinical participants, to assess item comprehensibility for the target population. No further adjustment was required.

Procedure

This study was completed entirely online, hosted by the questionnaire tool Qualtrics. Recruitment advertisements included a link placed on the main social networks (i.e., Facebook, Twitter) and websites of various local clinical centers specialized in the treatment and rehabilitation of EDs in Italy. In addition, flyers were placed around University campuses and in clinical waiting rooms of local ED services. The initial page contained a detailed description of the study, inclusion, and exclusion criteria along with any potential risks that may occur as a result of participation. Subjects were then asked to acknowledge they had read the terms and conditions and were aware of any potential risks by signing an informed consent form. Following informed consent, participants were asked to report demographic information and to answer the study questionnaires. After completing the survey, they were given access to a debriefing page of the study aims, and methodology, and received contact details for support services.

Statistical analyses

To test the factorial structural model of the SMI-ED-SF a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed using ‘lavaan’ package [19, 20] for R software (R-core project [21, 22]). All the other statistical analysis were carried out with SPSS software (version 20.0, SPSS Inc., Bologna, Italy) [23].

As reported in Table 2, items’ descriptive statistics showed a non-normal distribution of some indicators. Therefore, in line with the previous study [13], the robust maximum likelihood method (MLM) [24,25,26,27] was chosen as estimator for the CFA. The MLM is a robust variant of the Maximum likelihood [27] that provides robust standard errors and is also referred to as the Satorra–Bentler Chi square (S–Bχ2) [19, 28, 29] to assess the model fit. Other fit indexes used to assess the model fit [30] were: the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) [31, 32], the comparative fit index (CFI) [33], and the standard root mean square residual (SRMR) [27], and the ratio of S–Bχ2 to the degrees of freedom (df) [34]. A S–Bχ2 test non-significant is desirable [35]. The RMSEA expresses fit per degrees of freedom of the model, with values lower than 0.08 suggesting an acceptable model fit [36] and values below 0.05 indicating a good fit [37]. The CFI designates the amount of variance and covariance accounted by the model compared with a baseline model, with values between 0.90 and 0.95 considered an acceptable fit [38, 39], and values > 0.95 indicating a good fit [36].

However, Kenny and McCoach mathematically demonstrate that a higher number of indicators analyzed negatively affects this fit index [40,41,42]. The SRMR derives from the residual correlation matrix and represents the average discrepancy between the correlations observed in the input matrix and those predicted by the model [27, 38]. A cutoff value higher than 0.08 is considered good [26, 36]. Also, the χ2/df ratio is considered as an easily computable measure of fit [26, 43], and a χ2/df ratio value of 3 or less indicates good fit [44,45,46,47].

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used as measure of internal consistency for each SMI-ED-SF subscale—and values higher than 0.7 are deemed acceptable [48]. However, considering the differences in the magnitude of SMI-ED-SF’s factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha was supported by Raykov’s maximal reliability (MR) [49] and the Bentler’s “Model-Based Internal Consistency Coefficient” (MBICC) [50]. These two indices were, respectively, chosen as measures of internal consistency of each single factor and multidimensional (overall) reliability: values higher than 0.6 suggest good reliability [51].

In addition, a MANCOVA was conducted to assess for possible statistical differences between the disordered eating subgroups simultaneously, on the SMI-ED-SF subscales, while adjusting for differences in age and gender.

Results

Sample characteristics

Participants’ self-reported BMI ranged from 13.71 to 65.31 (mean = 28.26; SD = 10.54), with 15.7% of the sample having a BMI below 18.5 and 38.4% of the respondents having a BMI above 30.1.

Of 649 participants, 46 self-reported a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa (AN), 31 were diagnosed with bulimia nervosa (BN), 64 suffered from binge eating disorder (BED), and 58 declared eating disorders not otherwise specified (EDNOS)—while the remaining 450 participants did not self-report a diagnosis of EDs. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

Structural validity

Item analysis revealed a non-perfect normal distribution, with Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests being significant (p < .001). Skewness ranged between − 1.18 and 2.76 (meansk = 0.79, SDsk = 0.81), and kurtosis ranged between − 1.03 and 8.09 (meank = 0.64, SDk = 2.01) (Table 2).

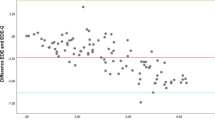

In line with the SMI-ED validation study [13], results from the CFA suggested an acceptable 16-correlated-factors solution for the SMI-ED-SF, despite not all the model’s fit indexes reaching the desired value [36]. Indeed, the Satorra–Bentler Chi square model for fit was statistically significant [S–Bχ2 (1832) = 3324.799; p < .001] and the CFI value did not achieve the threshold (CFI > 0.90 [38, 39]: CFI = 0.880). However, the RMSEA showed a good approximation fit of the model to the data [RMSEA = 0.045 (90% CI from 0.043 to 0.048), p(RMSEA < 0.05) = 1], and the SRMR also accounted for the goodness of the model (SRMR = 0.066 [36]). By dividing the χ2 for the degrees of freedom (df) of the model [34, 36], the model further resulted acceptable (χ2/df = 1.81; < 3) [26].

As reported in Table 2, each item loaded significantly on its associated factor (p < .001), meanloadings = 0.698; SDloadings = 0.122; ranging from 0.339 (item#22) to 0.901 (item#11). Correlations between the 16 factors ranged from |0.065| to |0.654|; meanr-factors = 0.238; SDr-factors = 0.297 (Table 3).

Concurrent validity: correlation between SMI-ED-SF factors and eating disorder variables

Most SMI-ED-SF factors were significantly associated (ranging from |0.088| to |0.855|) with the EDE-Q subscales and ED symptoms (Table 4). In line with the original SMI-ED the adaptive modes (happy child and healthy adult) were negatively correlated with all the ED variables.

Correlation between SMI-ED-SF factors, gender, age, and BMI

Most of the SMI-ED-SF factors were not significantly associated with gender, age and BMI (Table 5). Regarding gender, significant associations ranged from |0.084| (angry child) to |0.235| (vulnerable child). Considering age, statistically significant correlations ranged from |0.079| (happy child) to |0.197| (helpless surrenderer). Also, significant correlations between the SMI-ED-SF factors and BMI ranged from |0.099| (self-aggrandizer) and |0.168| (eating disorder overcontroller).

Mode scores across disordered eating subscales

While controlling for age and gender as possible confounding variables, the MANCOVA revealed a significant difference between the presence of a self-reported diagnosis of ED and most of the SMI-ED-SF subscales: Wilks’s Λ = 0.638, F = 4.587, p < .001, partial η2 = 106. No differences emerged between ED diagnoses and the enraged child mode measured by the SMI-ED-SF. Also, to test differences between groups within the SMI-ED-SF subscales, ANCOVAs with focused contrasts were conducted for each dependent variable (Table 6).

Participants with no self-reported diagnosis of EDs showed lower means for each maladaptive mode as well as higher means for the adaptive modes, thus suggesting the goodness of the SMI-ED-SF in discriminating between the clinical and the general population.

Discussion

This study tested the psychometric properties of the shorter version of the Schema Mode Inventory for disordered eating both for the general population and a clinical sample, in Italy.

Findings confirmed an adequate fit for the 16-factor model, with moderate intercorrelations between subscales. However, the Satorra-Bentler Chi square was statistically significant and the CFI values did not achieve the desired cutoff score (CFI > 0.90 [38, 39]: CFI = 0.880). They may have been affected by the sample size (i.e., Chi square [34, 35, 52,53,54]) and the number of considered indicators, (i.e., CFI [36, 40,41,42, 46, 54,55,56]) respectively, but, since both the SRMR and RMSEA accounted for the goodness of the model, this is not reason for concern [40]. Also, internal consistency within subscales was high, and the scale showed good overall reliability.

As expected, disordered eating behaviours were positively correlated with most of the negative coping modes, and negatively related to the healthy modes (healthy adult and happy child). Specifically, the overcontroller mode and the helpless surrenderer dimensions (explicitly designating the presence of disordered eating patterns) showed moderate-to-high correlations with the eating/weight/shape concerns subscales of the EDE-Q, as well as with the EDE-Q global score. Consistently, higher mean scores for the Healthy Modes were noticed in respondents with no self-reported diagnosis of EDs.

Findings from this study reflect those observed by testing the psychometric properties of the Schema Mode Inventory for eating Disorders (SMI-ED) [13]—the adapted version of the Schema Mode Inventory (SMI) for the measurement of mode states within a population with self-reported disordered eating behaviours [18]—but overcome some of its methodological and practical limitations. In fact, unlike for the SMI-ED validation study, participants were recruited from both clinical and non-clinical populations, thus supporting the discriminatory power of the tool and its ability to identify individuals at risk/with disordered eating behaviours. By assessing the psychometric proprieties of the questionnaire in Italian—and demonstrating their goodness of fit—further evidence was also reached for both its construct and external validity. Moreover, a meaningful item reduction resulting in the development of a new shorter instrument in Italian increases the scale usability for both clinical and research purposes.

Nonetheless, these results should be considered a first step in the validation process of the SMI-ED-SF, and as a promising starting point for future research on the topic. In fact, as the sample was purely recruited via online survey, it has its limitations. First, it was not possible to ensure gender homogeneity among respondents—although a smaller proportion of males is representative of the gender ratio usually found in clinical settings [57]. Also, a relatively low proportion of participants revealed binge eating behaviours compared with other dysfunctional eating patterns, and the percentage of respondents who had never been diagnosed with an ED doubled its counterpart. In addition, asking people to self-report an existing diagnosis of EDs may have led to under-represent both those with reduced capacity to acknowledge their ED patterns, and individuals with severe EDs but avoidant of support services.

Future studies should ideally include a larger percentage of males in the sample, and all ED subgroups should be adequately represented within the sample to more precisely determine whether specific profiles of schema modes exist within a given diagnostic group, and the degree to which this is statistically feasible. The measurement invariance between clinical and non-clinical populations should also be tested to ascertain whether the questionnaire is valid to measure schema modes in each group separately.

Conclusion

This scale is of significant value for clinicians and researchers in identifying and exploring mechanisms through which schema modes are expressed within the ED population—both quantitatively and qualitatively. In fact,—as the SMI-ED—the SMI-ED-SF not only provides information regarding modes that would not be otherwise accessible in the original SMI [18], but—because of its reduced number of items—it facilitates the capacity to make important links between ED symptoms and schema modes, and in developing individually tailored case conceptualizations and treatments.

In fact, although CBT is widely recognized as the gold standard intervention for adults with EDs, it is still restricted to the ineffective coping mechanisms maintaining the problem [58], without adequately addressing early life experiences often at the root of the painful or unhelpful ways of thinking, feeling and behaving typical of clients with EDs. Evidence supports the effectiveness of ST in facilitating behavioural change both through diminishing the emotional intensity of memories linked to EMS [and associated ED symptoms], alongside direct behavioural pattern-breaking. The development of a measure specifically aimed at facilitating a more precise measurement of mode states within the ED population will enable clinicians to provide more sophisticated conceptualizations and therapeutic opportunities for those with EDs, and to enhance long-term maintenance of the achieved results [10].

Change history

09 March 2019

The article <Emphasis Type="Italic">Evaluation of the reliability and validity of the Italian version</Emphasis>.

References

Fassino S, Abbate-Daga G (2013) Resistance to treatment in eating disorders: a critical challenge. BMC Psychiatry 13:282. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-282

Pietrabissa G (2018) Group motivation-focused interventions for patients with obesity and binge eating disorder. Front Psychol 9:1104. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01104

Sorgente A et al (2017) Web-based interventions for weight loss or weight loss maintenance in overweight and obese people: a systematic review of systematic reviews. J Med Internet Res 19(6):e229. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6972

Grilo CM (2017) Psychological and behavioral treatments for binge-eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 78(Suppl 1):20–24. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.sh16003su1c.04

Linardon J, Brennan L (2017) The effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders on quality of life: a meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord 50(7):715–730. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22719

Agras WS, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Wilfley DE (2017) Evolution of cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders. Behav Res Ther 88:26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.09.004

Castelnuovo G et al (2017) Cognitive behavioral therapy to aid weight loss in obese patients: current perspectives. Psychol Res Behav Manag 10:165–173. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S113278

Young JE, Klosko JS, Weishaar ME (2003) Schema therapy: a practitioner’s guide. The Guilford Press, New York

Bamelis LL et al (2014) Results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness of schema therapy for personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 171(3):305–322. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12040518

Castelnuovo G et al (2016) Not only clinical efficacy in psychological treatments: clinical psychology must promote cost-benefit, cost-effectiveness, and cost-utility analysis. Front Psychol 7:563. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00563

Talbot D et al (2015) Schema modes in eating disorders compared to a community sample. J Eat Disord 3:41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-015-0082-y

Voderholzer U et al (2014) A comparison of schemas, schema modes and childhood traumas in obsessive–compulsive disorder, chronic pain disorder and eating disorders. Psychopathology 47(1):24–31. https://doi.org/10.1159/000348484

Simpson SG et al (2018) Factorial structure and preliminary validation of the schema mode inventory for eating disorders (SMI-ED). Front Psychol 9:600. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00600

MacCallum RC et al (1999) Sample size in factor analysis. Psychol Methods 4:84–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.4.1.84

Terwee CB et al (2007) Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 60:34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington

Calugi S et al (2017) The eating disorder examination questionnaire: reliability and validity of the Italian version. Eat Weight Disord 22(3):509–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0276-6

Young JE et al (2007) The schema mode inventory. Schema Therapy Institute, New York

Rosseel Y (2012) lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw 48(2):1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Rosseel Y et al (2015) Package ‘lavaan’. Retrieved from http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lavaan/lavaan.pdf. http://lavaan.org. pp 1–89

R Core Team (2014) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria

R Core Team (2014) The R project for statistical computing. https://www.r-project.org/

Nie NH, Bent DH, Hull CH (1970) SPSS: statistical package for the social sciences. McGraw-Hill, New York

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998–2012) Mplus user’s guide, 7th edn. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles

Muthén B, du SHC, Toit, Spisic D (1997) Robust inference using weighted least squares and quadratic estimating equations in latent variable modeling with categorical and continuous outcomes. Psychometrika 75(1):40–45

Hoyle RH (2012) Handbook of strucural equation modeling. The Guilford Press, New York

Bentler PM (1995) EQS structural equation program manual, in multivariate software. CA, Encino

Satorra A, Bentler PM (1988) Scaling corrections for chi-square statistics in covariance structure analysis. In: Business and economic section of the American Statistical Association. American Statistical Association, Alexandria

Satorra A, Bentler PM (1994) Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In: von Eye A, CC Clogg (eds) Latent variables analysis: applications for developmental research. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Barrett P (2007) Structural equation modelling: adjudging model fit. Person Indiv Diff 42(5):815–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.018

Steiger JH, Lind JC (1980) Statistically-based test for the number of common factors, in annual meeting of the Psychometric Society, Iowa City, IA

Steiger JH (1990) Structural model evaluation and modification: an interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behav Res 25(2):173–180. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4

Bentler PM (1990) Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull 107(2):238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

Jöreskog KG (1969) A general approach to confirmatory maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika 34:183–202

Bentler PM, Bonett DG (1980) Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol Bull 88:588–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 6:1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Browne MW, Cudeck R (1990) Single sample cross-validation indices for covariance structures. Multivariate Behav Res 24:445–455. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr2404_4

Brown TA (2015) Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research, 2nd edn. In: TD Little (ed) The Guilford Press, New York

Browne MW, Cudeck R (1993) Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol Methods Res 21(2):230–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124192021002005

Kenny DA, McCoach DB (2003) Effect of the number of variables on measures of fit in structural equation modeling. Struct Equ Model 10(3):333–351. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM1003_1

Russell DW (2002) In search of underlying dimensions: the use (and abuse) of factor analysis in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. Person Soc Psychol Bull 28(12):1629–1646. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616702237645

Iacobucci D (2010) Structural equations modeling: Fit indices, sample size, and advanced topics. J Consumer Psychol 20(1):90–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2009.09.003

Marsh HW, Hocevar D (1985) Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: first-and higher order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychol Bull. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.97.3.562

Wheaton B (1977) Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. In: Heise DR (ed) Sociological methodology. Jossey-Bass, Inc., San Francisco, pp 84–136

Manzoni GM et al (2018) Feasibility, validity, and reliability of the italian pediatric quality of life inventory multidimensional fatigue scale for adults in inpatients with severe obesity. Obes Facts 11(1):25–36. https://doi.org/10.1159/000484565

Manzoni GM et al (2018) Validation of the Italian Yale Food Addiction Scale in postgraduate university students. Eat Weight Disord 23(2):167–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0495-0

Pietrabissa G et al (2017) Stages of change in obesity and weight management: factorial structure of the Italian version of the University of Rhode Island Change Assessment Scale. Eat Weight Disord 22(2):361–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0289-1

Cronbach LJ (1951) Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16(3):297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

Raykov T (2012) Scale construction and development using structural equation modeling. In: Hoyle RH (ed) Handbook of structural equation modeling. The Guilford Press, New York, pp 472–492

Bentler PM (2009) Alpha, dimension-free, and model-based internal consistency reiability. Psychometrika 74(1):137–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-008-9100-1

Barbaranelli C et al (2014) Dimensionality and reliability of the self-care of heart failure index scales: further evidence from confirmatory factor analysis. Res Nurs Health 37(6):524–537. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21623

Tuker LR, Lewis C (1973) A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika 38:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291170

James LR, Mulaik SA (1982) Causal analysis: assumptions, models and data. Sage, Beverly Hills

Kline RB (2015) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. The Guilford Press, New York

Fan X, Sivo SA (2005) Sensitivity of fit indexes to misspecified structural or measurement model components. Struct Equ Model 12(3):343–367

Hu L, Bentler PM (1998) Fit indexes in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to under parameterized model misspecification. Sychol Methods 3(4):424–453

Striegel-Moore RH et al (2009) Gender difference in the prevalence of eating disorder symptoms. Int J Eat Disord 42(5):471–474. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20625

Waller G, Kennerley H (2003) Cognitive-behavioral treatments. In: Treasure J, Schmidt U, Furth E (eds) Handbook of eating disorders. Wiley, Chichester, pp 233–252

Acknowledgements

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The Medical Ethics Committee of Istituto Auxologico Italiano approved the study protocol and the informed consent process.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

All procedures performed in studies were run in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The Medical Ethics Committee of Istituto Auxologico Italiano approved the study protocol and the informed consent process.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original article was revised to update the copyright information.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pietrabissa, G., Rossi, A., Simpson, S. et al. Evaluation of the reliability and validity of the Italian version of the schema mode inventory for eating disorders: short form for adults with dysfunctional eating behaviors. Eat Weight Disord 25, 553–565 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00644-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00644-5