Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to examine the relationships between perceived weight stigma, eating disturbances, and emotional distress across individuals with different self-perceived weight status.

Methods

University students from Hong Kong (n = 400) and Taiwan (n = 307) participated in this study and completed several questionnaires: Perceived Weight Stigma questionnaire; Three-factor Eating Questionnaire; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Each participant self-reported their height, weight, and self-perceived weight status.

Results

After controlling for demographics, perceived weight stigma was associated with eating disturbances (β = 0.223, p < 0.001), depression (β = 0.143, p < 0.001), and anxiety (β = 0.193, p < 0.001); and eating disturbances was associated with depression (β = 0.147, p < 0.001) and anxiety (β = 0.300, p < 0.001) in the whole sample. Additionally, eating disturbances mediated the association between perceived weight stigma and emotional distress. Similar findings were shown in the subsamples who perceived themselves as higher weight or normal weight and in the male and female subsamples. However, in the subsamples who perceived themselves as lower weight, only the links between eating disturbances and emotional distress were significant.

Conclusion

Perceived weight stigma was associated with eating disturbances and emotional distress in young adults with both higher and normal weight. Eating disturbances were associated with emotional distress regardless of participants’ weight status.

Level of evidence

Level V, cross-sectional descriptive study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dim views toward irregular weight status are commonly held, especially regarding the profound negative impacts that overweight and underweight statuses can have on health, including psychosocial health [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Although medical weight terms (e.g., overweight, underweight, and obese) help healthcare providers understand the physical health of an individual, many find that these terms are stigmatized [7]. Therefore, the use of high(er) and low(er) weight to indicate an individual’s status is favorable to eliminate weight bias. Additionally, the impaired psychosocial outcomes in higher weight individuals have been further investigated, and the current literature indicates that a possible mediator between obesity and the outcomes is weight stigma (or weight bias) [8]. Indeed, studies found that higher weight individuals are perceived as being less attractive than those with normal weight or those with a thin figure, have a lower chance of being employed, and have a higher chance of being teased [8]. These stigmatizing experiences may consequentially cause emotional distress, including depression and anxiety, for higher weight individuals [9,10,11]. Unfortunately, many adolescents and young adults, regardless of their weight status, are likely to accept and endorse weight-biased beliefs [11,12,13,14], and subsequently internalize this bias. They may also experience associated eating disturbances or emotional distress [15]. O’Brien et al. [10] and Schvey and White [16] found that experienced or internalized weight stigma is associated with disordered eating behaviors. O’Brien et al. [10] also indicated that among non-overweight young adults, the reported weight stigma was moderately correlated with their reported emotional distress. However, a recent systematic review reveals that issues related to weight-related self-stigma are understudied, and more evidence is needed [17].

Along with emotional distress, eating disturbances are an additional negative consequence that may be caused by weight bias [10, 11]; eating disturbances may result from weight-related self-stigma through weight-related experiential avoidance [18]. Eating disturbances include binge eating, purging, emotional eating and uncontrolled eating and could indicate heightened medical and psychiatric comorbidities [19, 20]. Although higher weight people engage in the highest rates of restrictive disordered eating, eating disturbances associated with elevated emotional distress occur throughout all weight levels [19, 20]. Therefore, weight bias, eating disturbances, and emotional distress are three important factors that are mutually correlated among people regardless of their weight status. In East Asia, however, demonstrative evidence of the aforementioned correlations is little to none. Given that traditional viewpoints in East Asian culture (or specifically, Chinese) value rotundity, yet modern viewpoints glorify slenderness [12, 14], the need for empirical evidence on the topic of weight stigma among Chinese people is dire.

Gender also plays a significant role in the relationships between weight bias, eating disturbances, and emotional distress. Although some studies found that there was no significant gender difference within weight bias and binge eating [21, 22], other research has shown that males and females endure different impacts of weight-based teasing and perceived pressure to be thin [23]. Therefore, the gender impacts within the topics of weight bias or weight stigma should not be ignored [12]. Given that there is a meager existence of the literature exploring gender differences in the correlations among weight bias, eating disturbances, and emotional distress, these correlations should be investigated to fill in the gap: especially in the Chinese population, where traditional culture regards higher weight males as rich and higher weight females as attractive and productive [12].

As an individual internalizes weight bias, self-perceived weight status may have a greater impact than objective weight status, as classified by body mass index (BMI) [4, 24,25,26], on mental health and behaviors. Studies have indicated that a distorted perception of one’s own weight status may contribute to psychological distress and eating disorders [25, 26]. Another study even found that self-perceived weight status outperformed self-reported BMI in predicting psychosocial health [4]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have implemented subgroups for separate self-perceived weight statuses to investigate the aforementioned relationships between weight bias, eating disturbances, and emotional distress. Specifically, people with different self-perceived weight status may have different correlations between weight bias, anxiety, and depression. Consequently, healthcare providers may take different self-identified weight status categories into consideration when providing services.

Another literature gap that has yet to be addressed is the nature of these relationships among Asian populations. While research suggests that body dissatisfaction, eating disturbances and their negative consequences are important public health issues in Asian samples [27,28,29], their relationships with weight bias have not yet been investigated, and further research is needed. One study [30] examines weight stigma and coping strategies in racial subsamples including Asians. However, Himmelstein et al. [30] collected data in the US, and the cultural impacts on their Asia participants are not comparable to those living outside the US. Empirical studies explicitly demonstrate that westernized Asian regions, including Hong Kong and Taiwan, have adopted the ideation that thinness is beautiful [27, 31]. Nevertheless, this contradicts traditional Chinese thinking that plumpness symbolizes attractive women and rich men.

The present investigation aimed to study the relationships between weight stigma, eating disturbances, and emotional distress in subgroups with different self-perceived weight statuses and genders in Asian samples across two areas (Hong Kong and Taiwan). We hypothesized that (1) perceived weight stigma would be a significant predictor that is positively related to eating disturbances and emotional distress (including depression and anxiety); (2) eating disturbance would be a significant predictor that is positively related to emotional distress; (3) eating disturbance would be a significant mediator in the association of perceived weight stigma and emotional distress. As we had no clear direction to hypothesize whether the aforementioned relationships exist similarly between groups with different self-perceived weight status or between males and females, we simply explored the associations and did not make any hypothesis based on self-perceived weight status and gender.

Methods

Participants and procedure

We obtained approval from the ethics committee at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. All the participants provided a written informed consent to verify their willingness to participate without incentives after they fully understood the study purpose and procedure. The inclusion criteria included an understanding of traditional Chinese characters and age between 18 and 30. In addition, we excluded those who had chronic diseases [e.g., mental health problems including eating disorders (n = 0), physical impairments (n = 1), and learning disabilities (n = 1) that would have impaired ability to read the questionnaires]. All the participants were recruited from universities in either Hong Kong (n = 400) or Taiwan (n = 307). Several research assistants distributed the anonymous questionnaires during the last 20 min of a class. The participants were informed of the study purpose and procedure; it was emphasized that participation or non-participation would not impact their academic grades. In detail, the teaching faculties introduced our research assistants at the end of class and then left the classroom. The research assistants not only introduced the study purpose but also informed the students that the research was not related to the students’ specific study field and that they were free to leave without fear of penalty. Afterward, the research assistants delivered the questionnaires, which did not ask for any personal information except those we described below in “Instruments” section. Moreover, none of the research assistants were familiar with any of the participating students.

Instruments

All the participants completed the three questionnaires described below as well as a background information sheet that included their gender, age, self-perceived weight status, self-reported height, and self-reported weight. We made further use of their height and weight to calculate their BMI.

Perceived weight stigma questionnaire (PWS)

The PWS was constructed using 10 dichotomous items (yes scores 1 and no scores 0; sample item: people behave as if you are inferior because of your weight status; detailed items on Online Appendix A) that were adapted from the studies of Schafer and Ferraro [32] and Williams et al. [33]. The internal consistency shown in the study of Williams et al. [33] was satisfactory (α = 0.88). The 10 items of the PWS were summed to represent the level of perceived weight stigma, with a higher score indicating a higher level. The internal consistency of the PWS was acceptable in the whole current sample (α = 0.84), and subsamples in different gender, weight status, and living areas [Hong Kong or Taiwan]; (α = 0.80–0.86).

Three-factor eating questionnaire-18 (TFEQ)

The TFEQ is a self-report questionnaire that measures eating disturbances in three domains of restrained eating, uncontrolled eating, and emotional eating (sample item: I deliberately take small helpings as a means of controlling my weight). The internal consistency of the TFEQ was adequate (α = 0.78–0.87) and all the items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale [34, 35]. We used the overall score of the TFEQ to represent eating disturbance, with higher scores indicating greater disturbance. There was also acceptable internal consistency of the TFEQ in the subsamples of different gender, weight status, and living areas [Hong Kong or Taiwan]; (α = 0.79–0.82).

Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)

The HADS is a self-report questionnaire that measures emotional distress in two domains, anxiety and depression (sample item: I feel as if I am slowed down). Each domain of the HADS contains 7 items rated using a four-point Likert-type scale: “Yes, definitely”, “Yes, sometimes”, “No, not much”, and “No, not at all” scoring from 0 to 3. The psychometric properties of the HADS have been validated in different populations with adequate internal consistency (α = 0.76–0.82) and construct validity [36, 37]. The internal consistency of the HADS was acceptable in the whole current sample (α = 0.62 and 0.81), and subsamples in different gender, weight status, and living areas [Hong Kong or Taiwan]; (α = 0.79–0.83). After reverse coding the negatively worded items and summing up all the item scores, higher scores on the HADS indicate a greater level of anxiety or depression.

Data analysis

Frequency or mean was used to demonstrate the participants’ characteristics, including their instrument scores. Before examining our hypothesized model, we first tested measurement invariance to ensure that combining the data recruited from Hong Kong and Taiwan is acceptable. Specifically, we used confirmatory factor analyses with diagonally weighted least squares estimator to test the factorial structure of the three instruments (PWS, TFEQ, and HADS). In each factorial structure of the instrument, there were three nested models: a configural model (without any constraints across Hong Kong and Taiwan data); a model constraining factor loading held equal across Hong Kong and Taiwan data; a model constraining factor loadings and item intercepts held equal across Hong Kong and Taiwan data. We consider it acceptable to combine Hong Kong and Taiwan data if either of the following criteria was achieved: (1) the differences in comparative fit index (CFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) between every two nested models were > − 0.01 or < 0.02, respectively; (2) the model constraining factor loadings and item intercepts held equal across Hong Kong and Taiwan data had satisfactory CFI (> 0.9) and RMSEA (< 0.08) [38,39,40,41,42].

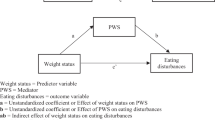

Structural equation modeling (SEM) using maximum likelihood estimator was applied to test our hypothesized model: perceived weight stigma is a predictor for eating disturbances and emotional distress (including depression and anxiety); eating disturbance is a predictor for emotional distress and is a mediator in the association between perceived weight stigma and emotional distress (see Figs. 1 or 2 for the conceptual model). Bootstrapping methods were used to examine whether the mediated effects existed. In addition to testing the model on the entire sample, we tested the same model in different subgroups stratified using self-perceived weight status (self-perceived higher weight, normal weight, and lower weight) and stratified using gender (male and female). For the subgroups stratified using self-perceived weight status, we controlled for age, gender, and BMI; for the subgroups stratified using gender, we controlled for age and self-perceived weight status (BMI was not controlled for because it was highly correlated to self-perceived weight status). We simply used the path analyses instead of adopting latent constructs in all the models because we want to fulfill the principle of parsimony and maintain the consistency for all measured constructs. That is, there would be 42 observed variables in the model if we applied latent constructs to all the measures.

Mediated effects of eating disturbances in the association between perceived weight stigma and emotional distress. a All sample; b higher weight; c normal weight; d lower weight; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; age, gender, and body mass index were controlled. Dashed lines indicate nonsignificant paths; solid lines indicate significant paths

Mediated effects of eating disturbances in the association between perceived weight stigma and emotional distress for each gender. a Females; b males; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; age and perceived weight status were controlled. Dashed lines indicate nonsignificant paths; solid lines indicate significant paths

All the statistics were done using R software, and the SEM was conducted by the lavaan package (http://lavaan.ugent.be/).

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants (N = 707) and Table 2 demonstrates that Hong Kong participants and Taiwan participants did not have substantial differences in understanding and responding to the three instruments. The following models were analyzed using all the 707 participants together.

Additionally, Table 3 demonstrates the correlation among all the studied variables; Table 4 illustrates the differences between Hong Kong and Taiwan participants in the scores of perceived weight stigma, eating disturbances, and emotional distress.

After controlling for age, gender, and BMI, all the paths proposed in our model had significant coefficients in the entire sample (Fig. 1a), where eating disturbances were a significant mediator in the association between perceived weight stigma and emotional distress (Table 5). In subsamples, self-perceived higher weight (Fig. 1b) and self-perceived normal weight (Fig. 1c) participants had similar findings to the entire sample in their significant paths and mediation effects. However, only the paths between eating disturbances and emotional distress (p = 0.033 for depression; = 0.007 for anxiety) had significant coefficients in lower weight people (Fig. 1d).

After controlling for age and perceived weight status, all the paths had significant coefficients in both genders (Fig. 2), except for the path between perceived weight stigma and depression in males (Fig. 2b). Eating disturbances significantly mediated in the association between perceived weight stigma and depression for males but not for females; eating disturbances mediated in the association between perceived weight stigma and anxiety for both genders (Table 6).

Discussion

In general, the hypothesized paths in the proposed model were all supported in the entire sample (Fig. 1a). After we separated the participants according to their self-perceived weight status, all the paths, except for the path between perceived weight stigma and depression, were still significant for those who self-perceived as higher weight or normal weight (Fig. 1b, c). For those who self-perceived as lower weight, only the paths between eating disturbances and emotional distress were significant (Fig. 1d). In addition, eating disturbances served as a significant mediator in the association between perceived weight stigma and anxiety for the entire sample and in each subsample, except for those who were lower weight.

Similar to previous findings [10, 15, 21, 23, 43], our findings also suggested that perceived weight stigma was associated with eating disturbances and emotional distress. O’Brien et al. [10] and Haines, Neumark–Sztainer, Eisenberg, and Hannan [44] proposed that emotional distress serves as a mediator in the association between weight stigma and eating disturbances. Haines et al. [44] stated that their finding of association between teasing and binge eating can be explained by depressive symptoms: depressive symptoms may lead to binge eating. O’Brien et al. [10] further postulated that perceived experiences of weight stigma increase the individual’s internalized bias, and that this increased self-stigma results in emotional distress and subsequent effects on eating behaviors.

However, the causality between emotional distress and eating disturbances has not yet been confirmed. We considered it worthwhile to test whether eating disturbances might mediate the association between perceived weight stigma and emotional distress. Our findings support our hypotheses and are in line with the findings of Zucker et al. [45]. Zucker et al. [45] used a cohort sample aged between 24 and 71 months to follow their eating behaviors and emotional distress. They found that as the eating behaviors of the children worsened, their depression and anxiety levels increased. Therefore, eating disturbances could also be a mediator. Nevertheless, given the nature of our cross-sectional design, we were unable to examine causal effects. Future studies using longitudinal or experimental designs are warranted to investigate the causal relationships between eating disturbance and emotional distress.

We found no relationship between the perceived weight stigma and eating disturbances in young adults with self-perceived lower weight, and this may be explained by the ideal of beauty as thinness [46]. Marini [47] found that pro-underweight preferences were observed among a sample of 4806 adults. Therefore, our participants who considered themselves lower weight may have more fully identified with their weight status because of the pro-underweight preferences (i.e., feeling satisfied with their lower weight status) and might not have the feelings of weight stigma. In contrast, our participants who considered themselves normal weight might still want to lose further weight, and they may also have perceived experiences of weight stigma.

Our results from participants with normal weight are consistent with findings from O’Brien et al. [10] and Haines et al. [44] that the associations between weight stigma and eating/emotional disturbances exist in normal weight people in addition to those who are higher weight. Hence, based on the findings from previous studies [10, 44] and from ours, healthcare providers should not ignore the impacts of weight stigma on eating and emotional disturbances in people with any weight status. Assessing self-perceived weight status may help healthcare providers to quickly determine whether a person has weight stigma issue: if the person self-perceives him or herself as lower weight, the impacts of perceived weight stigma may not be serious. Conversely, if the person does not self-perceive as lower weight, healthcare providers should further examine the likelihood of weight stigma issues.

Although some studies identified gender as a potential confounding variable in the relationships between weight bias, eating disturbances, and emotional distress [4, 23], our findings suggested that males and females performed similarly in the aforementioned relationships. While other studies also reported no significant gender differences in the relationship between weight bias and binge eating [21, 22], and we believe that our results are reliable, future studies are needed to clarify the role of gender in weight bias and eating disturbances. Indeed, Himmelstein et al. [48] found that nearly 40% of a male sample (n = 1513) reported experiencing weight stigma. Their findings somewhat corroborate what we found: Our findings from stratified gender suggest that weight stigma problems in males and in females warrant equal consideration from healthcare providers. That is, the negative consequences from perceived weight stigma do not only exist for females, but also in males. Although most research alludes that females are likely to exacerbate their eating or emotional disturbances by endorsing the concept of slim is beauty [12, 27, 31], our findings indicated notably similar affects in males.

There are some limitations to this study. First, our study design was cross-sectional, and causal effects cannot be determined. Although we proposed eating disturbances as the mediator in the association between perceived weight stigma and emotional distress; we were unable to ensure the sequence of the three factors. People are likely to have eating disturbances when they have emotional problems, while they are also likely to feel uncomfortable (e.g., guilty) because of their eating patterns. Therefore, a longitudinal design to test the causal relationships among these factors is needed. Second, all the participants were recruited from universities through convenience sampling. Therefore, the generalizability of our results might be restricted. For example, our participants were more likely to have better health literacy than general populations. In addition, our participants were all young adults who were apparently healthy, and future studies on other age groups (e.g., children and elderly) or on people with eating disorders are thus recommended. Third, the questionnaires used in the study were all subjective measures, and we were unable to control for social desirability effects. Fourth, there was no delineation between types of eating disturbance; thus, specific correlations between the perceived weight stigma and different types of eating disturbance remain understudied. Future studies are encouraged to further investigate this topic. Fifth, perceived weight stigma was assessed using a self-designed questionnaire (i.e., PWS), and its psychometric properties are understudied. However, given that its internal consistency was satisfactory in our current sample, we tentatively concluded that the psychometric property issues might not be serious. Nevertheless, future studies are encouraged to use well-established instruments to study perceived weight stigma. Finally, although many of our proposed paths were significant, a substantial amount of variance in each endogenous variable per model was still unaccounted for. Given that the most variance accounted for in a model was only about 20%, future studies are needed to investigate other significant factors that contributed to eating disturbances, depression, and anxiety. For example, Gan et al. [23] have found that social cultural influences (e.g., perceived pressure to be thin from significant others) could contribute to disordered eating or emotional distress. Additionally, some research proposes that internet use could be a potential determinant of eating disorders and mental health problems [49,50,51,52].

In conclusion, we found that perceived weight stigma was associated with eating disturbances and emotional distress in self-identified higher weight and normal weight young adults. We also found that the aforementioned associations were not present in lower weight adults. Furthermore, eating disturbances were associated with emotional distress regardless of the weight status of our participants. In terms of gender, perceived weight stigma was associated with eating disturbances and emotional distress, and eating disturbances were associated with emotional distress, in both males and females. Healthcare providers may want to consider self-perceived weight status and perceived weight stigma when they provide services to higher weight and normal weight people. This is especially pertinent for people who have a tendency toward abnormal eating patterns; healthcare providers could ascertain the existence of perceived weight stigma and provide prompt, appropriate treatment for stigma reduction, such as psychoeducation or motivational interviewing. Given that our findings indicate a relationship between eating disturbances and emotional distress, healthcare providers may also want to monitor emotional distress of these people who have a tendency toward abnormal eating patterns. Early intervention may prevent subsequent emotional distress.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Brisbois TD, Farmer AP, McCargar LJ (2012) Early markers of adult obesity: a review. Obes Rev 13(4):347–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00965.x

Lin C-Y (2019) Ethical issues of monitoring children’s weight status in school settings. Social Health Behav 2(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/SHB.SHB_37_18

Lin C-Y, Su C-T, Wang J-D, Ma H-I (2013) Self-rated and parent-rated quality of life (QoL) for community-based obese and overweight children. Acta Paediatr 102:e114–e119. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12108

Lin Y-C, Latner JD, Fung XCC, Lin C-Y (2018) Poor health and experiences of being bullied in adolescents: Self-perceived overweight and frustration with appearance matter. Obesity 26:397–404. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22041

Lorem GF, Schirmer H, Emaus N (2017) What is the impact of underweight on self-reported health trajectories and mortality rates: a cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 15(1):191. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0766-x

Skinner AC, Perrin EM, Skelton JA (2016) Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity in US children, 1999–2014. Obesity 24(5):1116–1123. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21497

Meadows A, Daníelsdóttir S (2016) What’s in a word? On weight stigma and terminology. Front Psychol 7:1527. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01527

Puhl RM, Heuer CA (2009) The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity 17:941–964. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.636

Myers A, Rosen JC (1999) Obesity stigmatization and coping: relation to mental health symptoms, body image, and self-esteem. Int J Obes 23:221–230

O’Brien KS, Latner JD, Puhl RM, Vartanian LR, Giles C, Griva K, Carter A (2016) The relationship between weight stigma and eating behavior is explained by weight bias internalization and psychological distress. Appetite 102:70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.032

Pearl RL, White MA, Grilo CM (2014) Weight bias internalization, depression, and self-reported health among overweight binge eating disorder patients. Obesity 22(5):E142–E148. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20617

Cheng MY, Wang S-M, Lam YY, Luk HT, Man YC, Lin C-Y (2018) The relationships between weight bias, perceived weight stigma, eating behavior and psychological distress among undergraduate students in Hong Kong. J Nerv Ment Dis 206:705–710. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000869

Essayli JH, Murakami JM, Wilson RE, Latner JD (2017) The impact of weight labels on body image, internalized weight stigma, affect, perceived health, and intended weight loss behaviors in normal-weight and overweight college women. Am J Health Promot 31(6):484–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117116661982

Wong PC, Hsieh Y-P, Ng HH, Kong SF, Chan KL, Au TYA, Lin C-Y, Fung XCC (2018) Investigating the self-stigma and quality of life for overweight/obese children in Hong Kong: a preliminary study. Child Ind Res Adv Online Publ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9573-0

Ashmore JA, Friedman KE, Reichmann SK, Musante GJ (2008) Weight-based stigmatization, psychological distress, & binge eating behavior among obese treatment-seeking adults. Eat Behav 9(2):203–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.09.006

Schvey NA, White MA (2015) The internalization of weight bias is associated with severe eating pathology among lean individuals. Eat Behav 17:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.11.001

Pearl RL, Puhl RM (2018) Weight bias internalization and health: a systematic review. Obes Rev 19(8):1141–1163. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12701

Palmeira L, Cunha M, Pinto-Gouveia J (2018) The weight of weight self-stigma in unhealthy eating behaviours: the mediator role of weight-related experiential avoidance. Eat Weight Disord 23(6):785–796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0540-z

Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, Kessler RC (2007) The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry 61:348–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

Grilo CM, White MA, Masheb RM (2009) DSM-IV Psychiatric disorder comorbidity and its correlates in binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 42:228–234. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20599

Salwen JK, Hymowitz GF, Bannon SM, O’Leary KD (2015) Weight-related abuse: perceived emotional impact and the effect on disordered eating. Child Abuse Negl 45:163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.12.005

Vartanian LR (2015) Development and validation of a brief version of the stigmatizing situations inventory. Obes Sci Pract 1:119–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/osp4.11

Gan WY, Mohd Nasir MT, Zalilah MS, Hazizi AS (2011) Direct and indirect effects of sociocultural influences on disordered eating among Malaysian male and female university students. A mediation analysis of psychological distress. Appetite 56(3):778–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.03.005

Duncan DT, Ding EL, Warner ET, Bennett GG, Wolin KY, Scharoun-Lee M (2011) Does perception equal reality? Weight misperception in relation to weight-related attitudes and behaviors among overweight and obese US adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 8(1):20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-8-20

Isomaa R, Isomaa AL, Marttunen M, Kaltiala-Heino R, Björkqvist K (2010) Psychological distress and risk for eating disorders in subgroups of dieters. Eur Eat Disord Rev 18:296–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1004

Isomaa R, Isomaa AL, Marttunen M, Kaltiala-Heino R, Björkqvist K (2011) Longitudinal concomitants of incorrect weight perception in female and male adolescents. Body Image 8:58–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.11.005

Lee S, Leung T, Lee AM, Yu H, Leung CM (1996) Body dissatisfaction among Chinese undergraduates and its implications for eating disorders in Hong Kong. Int J Eat Disord 20(1):77–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199607)20:1%3C77::AID-EAT9%3E3.0.CO;2-1

Mak KK, Lai CM (2011) The risks of disordered eating in Hong Kong adolescents. Eat Weight Disord 16(4):e289–e292. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03327475

Miri SF, Javadi M, Lin C-Y, Irandoost K, Rezazadeh A, Pakpour AH (2017) Health related quality of life and weight self-efficacy of life style among normal-weight, overweight and obese Iranian adolescents: a case control study. Int J Pediatr 5(11):5975–5984. https://doi.org/10.22038/IJP.2017.25554.2173

Himmelstein MS, Puhl RM, Quinn DM (2017) Intersectionality: an understudied framework for addressing weight stigma. Am J Prev Med 53(4):421–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.04.003

Wong Y, Huang YC (1999) Obesity concerns, weight satisfaction and characteristics of female dieters: a study on female Taiwanese college students. J Am Coll Nutr 18(2):194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.1999.10718850

Schafer MH, Ferraro KF (2011) The stigma of obesity: does perceived weight discrimination affect identity and physical health? Soc Psychol Q 74(1):76–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272511398197

Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB (1997) Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socioeconomic status, stress, and discrimination. J Health Psychol 2:335–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910539700200305

De Lauzon B, Romon M, Deschamps V et al (2004) The three-factor eating questionnaire-R18 is able to distinguish among different eating patterns in a general population. J Nutr 134(9):2372–2380. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/134.9.2372

Stunkard AJ, Messick S (1985) The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res 29(1):71–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8

Lin C-Y, Pakpour AH (2017) Using Hospital Anxiety and depression scale (HADS) on patients with epilepsy: confirmatory factor analysis and Rasch models. Seizure 45:42–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2016.11.019

Mykletun A, Stordal E, Dahl AA (2001) Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale: factor structure, item analyses and internal consistency in a large population. Br J Psychiatry 179:540–544. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.179.6.540

Yam C-W, Pakpour AH, Griffiths MD, Yau W-Y, Lo C-LM, Ng JMT, Lin C-Y, Leung H (2018) Psychometric testing of three Chinese online-related addictive behavior instruments among Hong Kong university students. Psychiatr Q. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-018-9610-7

Lin C-Y (2018) Comparing quality of life instruments: sizing them up versus PedsQL and Kid-KINDL. Social Health Behav 1(2):42–47. https://doi.org/10.4103/SHB.SHB_25_18

Pakpour AH, Chen C-Y, Lin C-Y, Strong C, Tsai M-C, Lin Y-C (2019) The relationship between children’s overweight and quality of life: a comparison of Sizing Me Up, PedsQL, and Kid-KINDL. Int J of Clin Health Psychol 19(1):49–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2018.06.002

Chang C-C, Su J-A, Chang K-C, Lin C-Y, Koschorke M, Thornicroft G (2018) Perceived stigma of caregivers: psychometric evaluation for devaluation of consumer families scale. Int J Clin Health Psychol 18(2):170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2017.12.003

Lin C-Y, Ku L-JE, Pakpour AH (2017) Measurement invariance across educational levels and gender in 12-Item Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) on caregivers of people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 29(11):1841–1848. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217001417

Puhl R, Suh Y (2015) Health consequences of weight stigma: Implications for obesity prevention and treatment. Curr Obes Rep 4(2):182–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-015-0153-z

Haines J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Eisenberg ME, Hannan PJ (2006) Weight teasing and disordered eating behaviors in adolescents: Longitudinal findings from project EAT (eating among teens). Pediatrics 117:209–215. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-1242

Zucker N, Copeland W, Franz L, Carpenter K, Keeling L, Angold A, Egger H (2015) Psychological and psychosocial impairment in preschoolers with selective eating. Pediatrics 136(3):e582–e590. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2386

Wiseman CV, Gray JJ, Mosimann JE, Ahrens AH (1992) Cultural expectations of thinness in women: an update. Int J Eat Disord 11:85–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(199201)11:1%3C85::AID-EAT2260110112%3E3.0.CO;2-T

Marini M (2017) Underweight vs. overweight/obese: which weight category do we prefer? Dissociation of weight-related preferences at the explicit and implicit level. Obes Sci Pract 3:390–398. https://doi.org/10.1002/osp4.136

Himmelstein MS, Puhl RM, Quinn DM (2018) Weight stigma in men: What, when, and by whom? Obesity (Silver Spring) 26(6):968–976. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22162

Tao ZL, Liu Y (2009) Is there a relationship between internet dependence and eating disorders? A comparison study of internet dependents and non-internet dependents. Eat Weight Disord 14:e77–e83. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03327803

Alpaslan AH, Kocak U, Avci K, Uzel Tas H (2015) The association between internet addiction and disordered eating attitudes among Turkish high school students. Eat Weight Disord 20:441–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0197-9

Strong C, Lee C-T, Cha L-H, Lin C-Y, Tsai M-C (2018) Adolescent internet use, social integration, and depressive symptoms: analysis from a longitudinal cohort survey. J Dev Behav Pediatr 39:318–324. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000553

Griffiths MD (2018) Five myths about gaming disorder. Soc Health Behav 1:2–3. https://doi.org/10.4103/SHB.SHB_21_18

Funding

This research was supported in part by (received funding from) the startup fund in the Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, CY., Strong, C., Latner, J.D. et al. Mediated effects of eating disturbances in the association of perceived weight stigma and emotional distress. Eat Weight Disord 25, 509–518 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00641-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00641-8