Abstract

Purpose

APOLO-Teens is an ongoing web-based program combining a manualized intervention delivered by Facebook®, a self-monitoring web application and monthly chat sessions to optimize treatment as usual for adolescents with overweight and obesity. The aims of this paper are twofold: (1) to describe the study protocol of the APOLO-Teens randomized controlled effectiveness trial and (2) to present baseline descriptive information of the Portuguese sample.

Methods

APOLO-Teens includes adolescents aged between 13 and 18 years with BMI percentile ≥ 85 (N = 210; 60.00% girls, BMI z-score 2.40 ± 0.75) undergoing hospital ambulatory treatment for overweight/obesity. Participants completed a set of self-report measures regarding eating behaviors and habits, psychological functioning (depression, anxiety, stress, and impulsivity), physical activity, and quality of life.

Results

Depression, anxiety, stress, impulsivity, and percentage body fat were inversely associated with health-related quality of life (rs = − 0.39 to − 0.62), while physical activity out-of-school was positively correlated with health-related quality of life (rs = 0.22). When compared to boys, girls demonstrated statistically significant higher scores on psychological distress, disturbed eating behaviors, impulsivity, were less active at school and had lower scores on the health-related quality of life (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

The results showed that there were gender differences in key psychological constructs that are likely to determine success with the treatment and that, therefore, need to be considered in future interventions. The results of APOLO-Teens randomized controlled trial will determine the impact of these constructs on the efficacy and adherence to a web-based intervention for weight loss in the Portuguese population.

Level of evidence:

Level V, cross-sectional descriptive study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Overweight and obesity in adolescence usually begin in early childhood and have been linked to the early onset of obesity-related complications, increased risk of adult obesity, and premature mortality during adulthood [1,2,3,4]. The prevalence of overweight and obesity in adolescents represents a major public heath burden [5, 6]. In 2013, 22.6% of girls and 23.8% of boys under 20 years, living in developed countries, were overweight or obese [4, 5].

Psychotherapeutic/behavioral programs, especially those based in cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), have been identified as key strategies for behavioral change, targeting changes in diet, and, consequently, improving body composition in adolescents with overweight or obesity [7,8,9,10]. However, more effective strategies are needed for weight loss programs, considering the current low quality of the scientific evidence and the small-to-moderate effects of these interventions on adolescents’ weight outcomes (BMI − 1.18 kg/m2, BMI z-score − 0.13 units, and body weight − 3.67 kg) [11,12,13]. In general, these low effects are partially aggravated by the fact that adherence to this type of interventions is generally low. Treatment options for weight loss are especially complex, time demanding, and expensive for both providers and patients [14, 15]. Consequently, there is a need for innovative and cost-effective treatment models to increase the effectiveness of the current treatment options in promoting/maintaining weight loss, in overweight/obese adolescents.

To overcome these limitations, our team developed the APOLO-Teens web-based intervention. This is a cognitive-behavioral lifestyle program delivered by Facebook® to optimize treatment as usual (TAU) for adolescents with overweight/obesity undergoing ambulatory treatment. It combines three components, a self-help manual implemented by Facebook® private groups, a self-monitoring system with automatic feedback messages and monthly chats sessions.

In fact, digital health can represent a powerful alternative tool to deliver validated interventions/strategies to adolescent patients and institutions in different areas such as health promotion, diagnosis, self-monitoring, treatment compliance (e.g., appointment attendance), and weight loss intervention programs [15, 16]. Research suggests that programs delivered by digital platforms, such as Facebook, represent great potentialities [17,18,19,20], since about 70% of adolescents use social networks, being Facebook one of the most popular [21]. In addition, other digital components such as chat sessions and self-monitoring systems for health behaviors with personalized feedback seem to increase the attractiveness of these interventions being associated with greater success in web-based intervention programs [22]. Not only these tools combine the growing accessibility to digital technology and devices, but they are also capable of reaching a wide number of individuals at a low cost [15].

Therefore, to better design and understand treatment outcomes in the context of digital interventions, behavioral, and psychological characteristics of adolescents with overweight and obesity under outpatient treatment should be further explored. Since psychological distress, eating behaviors, home food availability, and physical activity levels are related to weight outcomes and may contribute to the maintenance of excessive weight impeding therapeutic success [11, 23,24,25].

Thus, the aim of this paper is twofold: (1) to describe the study protocol for the effectiveness study of APOLO-Teens intervention and (2) to describe the baseline characteristics (anthropometry, overall/psychological functioning, eating, and physical activity) of the Portuguese adolescents undergoing weight loss treatment in two central hospitals who were randomized to enrol the APOLO-Teens Study protocol.

Methods

APOLO-Teens: the intervention

APOLO-Teens is a cognitive-behavioral lifestyle program that was designed to be delivered through Facebook and was developed to optimize TAU for adolescents with overweight or obesity undergoing ambulatory treatment in hospital centers. The APOLO-Teens program was specifically designed to: (1) increase weight loss; (2) promote compliance to the treatment as usual recommendations; (3) facilitate the adoption of healthy eating and physical activity behaviors; and (4) increase general wellbeing and quality of life (Fig. 1).

The program promotes behavioral change and weight loss through three key components, described below.

Facebook® group: self-help manual

This component provides psychoeducational information (weekly videos and daily images) on six different monthly topics through a Facebook private group. Topics as self-efficacy and motivation to change, physical activity, healthy eating, and eating problems, self-care, problem solving, and time management skills are addressed throughout the program. Each monthly topic is divided in four sub-topics, which are supported with a set of weekly cognitive-behavioral tasks related to each of the topics. Weekly cognitive-behavioral tasks support the trained skills in the context of this intervention.

Chat session

In APOLO-Teens, patients are invited to schedule a chat session for 20–30 min once a month via Facebook Messenger. The professional conducting the chat session is a master’s or PhD-level psychologist with more than 3 years of clinical experience under frequent supervision at the University of Minho.

Self-monitoring system with automatic feedback messages

APOLO-Teens allows patients to monitor relevant aspects regarding pre-programmed behaviors. Every week, patients have the possibility to answer to a standardized short assessment questionnaire on the status of different key features in the APOLO-Teens web application (http://www.apoloteens.com): (1) hours of physical activity; (2) sedentary time; and (3) consumption of fruits and vegetables. The computer program immediately evaluates the input information, and based on pre-programmed algorithms, the server automatically selects from a feedback messages’ pool a response to send immediately after the participant submits information. Each message is different and includes (a) an appreciation of the progress in the three key features; (b) reinforcement statement; and (c) alerts or suggestion on alternative behaviors in case of problem detection.

Example of a feedback message: ‘You ate fruit and vegetables every day and did a lot of physical exercise this week. Congratulations! Stay active and make an effort to decrease the time you spend playing computer games, watching TV or surfing on the Internet. Replace computer games for activities with friends or fitness games, and choose watch only the television shows that you love the most!’ Thumbs Up!

APOLO-Teens: description of the protocol for the effectiveness study

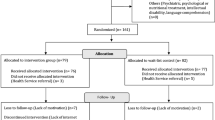

The effectiveness of APOLO-Teens is an ongoing intervention that uses a two-arm randomized controlled trial design: an internet-based cognitive-behavioral intervention group (IB-CBT) with access to the APOLO-Teens program for 6 months in addition to TAU, and a control group receiving only TAU (Fig. 2). The intervention is being delivered as a complement to TAU being provided at two public hospitals in the north of Portugal.

Variations in body mass index (BMI) z-score, frequency of healthy food consumption and physical activity will be considered to assess the effectiveness of this program. Other outcome measures include behavioral and psychological variables, namely, depression, anxiety, stress, impulsivity, eating behaviors (grazing, intuitive eating), physical activity, and health-related quality of life. As described in Fig. 2, there are several assessment moments throughout the intervention from the baseline (before the intervention) until 12 months after the end of APOLO-Teens intervention. All the self-report measures will be completed online via Qualtrics platform. Anthropometric data will be collected on hospital clinical appointments.

Recruitment

Participants meeting the following inclusion/exclusion criteria during recruitment are invited to participate in the study after their previous scheduled appointment at the public hospital with a nutritionist/pediatrician specialized in pediatric nutrition. Inclusion criteria for participation are: (1) aged between 13 and 18 years; (2) BMI percentile ≥ 85th; (3) enrolled in ambulatory treatment for overweight/obesity in one of the two Portuguese public hospital participating in this study; and (4) had a Facebook account and access to Internet at least three times per week. Patients with: (1) intellectual disabilities; (2) ambulatory movement limitations (e.g., use of walking stick, morpho-functional alterations as lower limb amputation, etc.); and (3) not being under other interventions for weight loss at the time of enrollment, are not eligible for participating in the study.

The study was approved by the university ethics review board and by the ethical committees from the hospital centers involved [São João Hospital Center (CHSJ), Oporto Hospital Center—Northern Maternal and Child Center (CMIN)]. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants’ parents/caregivers.

Measures

Anthropometry, clinical, and sociodemographic data

Anthropometric data: weight and body fat percentage are measured using a digital balance (Tanita® model TBF-300). Height is measured by a portable stadiometer (Seca® model 206).

Clinical–sociodemographic questionnaire addressing: sociodemographic family data, medical comorbidities, and medication.

Perceived health/weight status

Perceived health/weight status [26]: information about these constructs is collected through the questions “How would you rate your health overall?” (extremely poor, poor, fair, good, excellent) and “How would you rate your weight status?” (extremely underweight; underweight, right weight; overweight, obese). These questions are used to measure perceived health and perceived weight status, respectively. The last question was adapted to evaluate friends´ perception about the participant weight.

Eating behavior, physical activity, and overall/psychological functioning

Eating behavior

Meal frequency and household food availability: self-report frequency questionnaires are used to assess frequency of breakfast, lunch, snacks, and dinner in the last week (meal frequency) and typical household food availability of fruits, vegetables, candies, chocolates, potato chips, salty snacks, and soft drinks.

Children’s eating attitudes test (ChEAT) [27, 28]: ChEAT is a 26-item scale in which each item is rated in a Likert scale. This measure is composed by four subscales: (1) fear of getting fat; (2) restrictive and purging behaviors; (3) food preoccupation; and (4) social pressure to eat. ChEAT total score can range from 0 to 78, with higher scores indicating more eating behaviors disturbance (Cronbach’s α = 0.924).

Intuitive Eating Scale-2 (IES-2) [29,30,31]: IES assesses four components of intuitive eating by 23-item and is composed by four scales: (1) unconditional permission to eat when hungry and what food is desired; (2) eating for physical rather than emotional reasons; (3) reliance on internal hunger and satiety cues to determine when and how much to eat; and (4) body–food choice congruence. Higher total scores correspond with higher levels of intuitive eating and indicate more positive eating habits (Cronbach’s α = 0.755).

Repetitive Eating Questionnaire (Rep(eat)-Q) [32]: this self-report questionnaire assesses grazing-type eating pattern through 12 items evaluated by a Likert scale of 7 points. Higher scores indicate the presence of a grazing-type eating pattern (Cronbach’s α = 0.941).

Physical activity

Youth Activity Profile (YAP) [33]: the YAP is a 15 item self-administered questionnaire with 3 subscales to estimate physical activity and sedentary behavior in youth. The YAP was designed to estimate (1) activity at school, (2) activity outside of school, and (3) sedentary behaviors on the previous 7 days. The YAP is coded on a 1–5 Likert scale (low indicating less activity and vice versa), but has been calibrated to generate minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per week separately for each of the 3 sections (Cronbach’s α = 0.670).

Overall/psychological functioning assessment

Perception of self-efficacy—healthy lifestyle behaviors: this is a set of three questions to evaluate perception of self-efficacy related with the implementation of specific healthy lifestyle behaviors: (1) daily physical exercise; (2) consumption of at least three pieces of fruit per day, and (3) spend less than 2 h/day seated in front of a TV, computer, or tablet. Subjects assessed their perception of self-efficacy in a 0–100 scale for each behavior (0 = not capable; 100 = extremely capable). These questions were developed using the Bandura’s guide to construct self-efficacy scales.

UPPS-P (Negative urgency subscale) [34]: this is a 12 item scale that assesses the individual’s tendency to give in to strong impulses, specifically when accompanied by negative emotions such as depression, anxiety, or anger. Each item on the UPPS is rated on a four-point scale from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree (Cronbach’s α = 0.839).

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21) [35, 36]: this instrument includes 21 items and can provide scores for three subscales: depression, anxiety, and stress. The score of each subscale ranges between 0 and 21 points. Higher scores correspond to more negative affective states (Cronbach’s α = 0.947).

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory—PedsQL™ [37]: the PedsQL is a measure of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in children and adolescents with 21 items. This integrates four scales: physical functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, and school functioning as a psychosocial and physical health score and a total scale score (Cronbach’s α = 0.881).

Statistics

The primary aim of the APOLO-Teens effectiveness study is to explore predictors of weight loss, adherence, and behavioral change. Multiple linear regression analysis will be applied to explore predictors of weight loss and weight regain, and survival analyses to identify participants with the highest probability to regain weight. In addition, Three-Level Hierarchical Linear Models will be conducted to explore the temporal occurrence and patterns of change of eating-related variables, physical activity, and BMI in participants from the two groups.

The IBM® SPSS® Statistics 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for data analyses regarding the characterization of the APOLO-Teens participants baseline characteristics. Descriptive statistics were used to examine demographic and clinical characteristics. Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients were used to test bivariate associations between eating behavior, physical activity, and overall psychological functioning variables. Mann–Whitney test or t test for independent samples was used (upon deciding on normality of the data) to analyze differences between boys and girls in the different variables at baseline assessment. Just the Youth Activity Profile, Repetitive Eating Questionnaire, and Negative Urgency (UPPS) variables were normally distributed. For those skewness and kurtosis, values were within acceptable limits [38]. Variable means and standard deviations are presented in Table 3 for all the variables under study. No missing imputation techniques were used and participants with missing data were excluded from the final sample. p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

To describe the demographic, anthropometric and psychological characteristics of the Portuguese adolescents undergoing weight loss treatment only the data from the baseline assessment of APOLO-Teens study was considered. Baseline data were available from 210 adolescents (126; 60% girls and 84; 40% boys) undergoing hospital ambulatory treatment for overweight and obesity. Demographic and anthropometric characteristics of this study sample are displayed in Table 1, stratified by gender. No statistically significant differences were found between boys and girls regarding the assessed demographic and anthropometric variables in Table 1, with exception for age and percentage of body fat, which were significantly higher in girls. Both genders presented similar values for the other anthropometric variables.

In Table 2, correlation analyses between behavioral and psychological variables are presented. Higher values of depression, anxiety, stress, impulsivity, and percentage body fat were associated with lower scores of health-related quality of life (rs ranged from − 0.39 to − 0.62, p < 0.05). Physical activity out of the school was positively correlated with health-related quality of life. Correlation analyses were performed separately for girls and boys. In general, significant associations in Table 2 were maintained for both genders, with exception for percentage of body fat. It did not present a significant correlation with physical activity in school, impulsivity, and grazing behavior variables in both genders.

Perceived health/weight status

The distribution of health-related self-perception indicated that 22.8% of the participants considered their health as “poor” or “very poor”, 42.3% as “normal”, and 34.9% as “good” or “very good”. Regarding perceived weight status, 93.3% of the participants described themselves as “overweight” or “obese”, though 63.7% considered that their friends see them as “overweight” or obese. No statistically significant differences were found between genders in these variables, except for self-perceived weight status (U = 2065.0, p = 0.02). “Overweight” or “obese” perceived weight status was reported by 97.9% of the girls and 85.5% of the boys.

Meal frequency and household food availability

Meal frequency per week and household food availability of fruits, vegetables, candies, chocolates, potato chips, salty snacks, and soft drinks are depicted in Fig. 3. Most of the participants reported to have fruit (81.3%) and vegetables (76.6%) available at home “every day”. Unhealthy foods are reported to be consumed “sometimes” by most participants. Considering meal frequency per week, morning, afternoon, and evening snacks were the least frequent meals. Significant differences were found between boys and girls in frequency of morning snacks per week (U = 4261.0, p = 0.02), and availability of fruits at home (U = 4422.5, p < 0.00). Boys reported less consumption of morning snacks “everyday” (32.1%; 22.6% “never”) than girls (47.2% “everyday” and 13.6% “never”). In addition, 88.8% of girls reported availability of fruit at home almost “everyday” (0% “never”) compared to boys reporting 72.6% (3.6% “never”).

Eating behavior, physical activity, and overall/psychological functioning

The analysis of perception of self-efficacy related with the implementation of healthy lifestyle behaviors, in which the subjects assessed their perception of self-efficacy in a 0–100 scale showed a mean of 67.3 ± 24.2 for their confidence in being capable of doing physical exercise every day, 75.33 ± 29.7 for eating at least three pieces of fruit per day and 67.1 ± 24.5 for being capable of spending less than 2 h/day seated in front of a TV, computer or tablet. No significant differences were found between boys and girls.

Eating behavior, physical activity, and overall psychological functioning for girls and boys are described in Table 3. Statistically significant differences were found between boys and girls, with girls reporting less minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per day at school, more impulsivity (negative urgency) and lower scores in the health-related quality of life, physical, and psychological health. Girls also showed significant higher scores of depression, anxiety, and stress when compared with boys, as well as a higher eating behaviors disturbance, fear of getting fat and food preoccupation.

Discussion

This study described the APOLO-Teens study protocol and characterized a sample of Portuguese adolescents in hospital ambulatory treatment for overweight and obesity, in the context of APOLO-Teens baseline assessment. To the best of our knowledge, this project is the first that developed a specific, internet-based program using a social network (Facebook®) for adolescents with overweight and obesity undergoing hospital ambulatory treatment in public hospitals and, therefore, accessible to adolescents from low socioeconomic backgrounds. The results of the APOLO-Teens effectiveness study will add information about the feasibility and acceptability of this type of intervention, particularly in Portugal, adding data about baseline outcome predictors that can be helpful to tailor future web-based interventions.

The present study raises awareness about gender differences in adolescents in hospital ambulatory treatment for overweight and obesity, with special focus on girls whom seem to present an overall higher burden in psychological functioning, disordered eating behavior, less physical activity at school and health-related quality of life. These data suggest that girls may be a subgroup requiring specific attention to these psychological and behavioral aspects, which may contribute to the maintenance of obesity and/or preclude therapeutic success. In fact, these findings highlight the need for gender-sensitive interventions for pediatric obesity, including gender orientated modules especially designed to motivate girls to increase physical activity levels at school and to decrease psychological distress by dealing with the societal body ideal, frequently linked with the fear of getting fat, food preoccupation, and difficulties in impulsivity control. Boys may benefit from less intensive interventions on these topics.

Past research showed that a lower eating frequency seems to be related with a higher body weight status in adolescents [23]. Our findings about meal frequency support this data reveling a low eating frequency between adolescents in hospital ambulatory treatment for overweight and obesity, with lunch and dinner appearing as the mainly routine meals during the week. Breakfast and morning/afternoon snacks, in spite of being recommended by clinicians as essential daily meals, are not as frequent as expected in this specific population.

In addition, home food availability can play an important role in the quality of the diet of adolescents. Research has shown that there is a positive association between fruits and vegetables availability at home and intake of these foods among adolescents [23] and that the presence of healthy food items in the household is negatively correlated with caloric beverages and unhealthy snacks consumption in this population [24, 25]. Our analysis showed a good availability of fruit and vegetables (“almost every day”) in the home of adolescents in hospital ambulatory treatment for overweight and obesity. Nevertheless, there was still a noteworthy presence of high calorie foods, as candy, chocolates, soft drinks, and salty snacks available at least every week in their home, which can prevent adolescents from achieving a significant improvement on their diet’s quality.

BMI z-score was not associated with the disordered eating variables under study. This may be due to the low BMI z-score variability, since all adolescents in this sample had overweight and obesity. Yet, the rates of disordered eating behaviors are higher among adolescents with obesity [39, 40], and problematic eating behaviors have been related to weigh gain and several health, psychological, and social consequences, such as depressive symptomatology, anxiety, and impaired interpersonal functioning [41,42,43].

Regarding the study limitations is important to consider that the present data were obtained from a cross-sectional study using a convenience sample (acceptance rate 84%). In addition, the use of self-report measures can be associated with social desirability bias. These data were collected in public reference hospitals for pediatric obesity treatment in the north of Portugal, what assures it representativeness; nevertheless, it can prevent broaden generalizations. The major strengths of this study include the large sample size and the use of direct measures of weight and height. Further research is needed to explore if patient baseline characteristics and gender differences predict different patterns of change in the group intervention.

Our data have important clinical implications, since it alerts clinicians to the lifestyle and eating behaviors of this population, as well as to their psychological distress, mainly in female adolescents. Furthermore, the baseline characterization of this sample informs health care professionals about possible intervention specificities in this population, namely, the importance of morning/afternoon snacks (increasing meal frequency), attitudes regarding the relationship between overweight/obesity and poor health status, and the implementation of strategies to increase perception of self-efficacy in daily healthy lifestyle behaviors.

Conclusions

Girls in hospital ambulatory treatment for overweight and obesity seem to present an overall higher burden when compared with boys. Thus, the impact of gender differences on obesity treatment outcomes should be explored. Address strategies to increase meal frequency and physical activity, especially with girls, and assist families to decrease availability of unhealthy foods at home can be relevant to improve treatment outcomes in this specific population.

References

Adams KF, Leitzmann MF, Ballard-Barbash R et al (2014) Body mass and weight change in adults in relation to mortality risk. Am J Epidemiol 179:135–144. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt254

Engeland A, Bjørge T, Tverdal A, Søgaard AJ (2004) Obesity in adolescence and adulthood and the risk of adult mortality. Epidemiology 15:79–85. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ede.0000100148.40711.59

Kelsey MM, Zaepfel A, Bjornstad P, Nadeau KJ (2014) Age-related consequences of childhood obesity. Gerontology 60:222–228. https://doi.org/10.1159/000356023

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M et al (2014) Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 384:766–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8

Bibiloni MDM, Pons A, Tur JA (2013) Prevalence of overweight and obesity in adolescents: a systematic review. ISRN Obes. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/392747

Finkelstein EA, Graham WCK, Malhotra R (2014) Lifetime direct medical costs of childhood obesity. Pediatrics 133:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-0063

Tsiros MD, Sinn N, Brennan L et al (2008) Cognitive behavioral therapy improves diet and body composition in overweight and obese adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr 87:1134–1340

Lloyd-Richardson EE, Jelalian E, Sato AF et al (2012) Two-year follow-up of an adolescent behavioral weight control intervention. Pediatrics 130:281–288. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3283

Cooper Z, Fairburn C, Hawker D (2004) Cognitive-behavioral treatment of obesity: a clinician’s guide, 1st edn. The Guilford Press, New York

Vignolo M, Rossi F, Bardazza G et al (2008) Five-year follow-up of a cognitive-behavioural lifestyle multidisciplinary programme for childhood obesity outpatient treatment. Eur J Clin Nutr 62:1047–1057. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602819

Al-Khudairy L, Loveman E, Colquitt JL et al (2017) Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese adolescents aged 12 to 17 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012691

Whitlock EP, O’Connor EA, Williams SB et al (2010) Effectiveness of primary care interventions for weight management in children and adolescents: an updated, targeted systematic review for the USPSTF. Evid Synth. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-1955

Whitlock EP, O’Connor EA, Williams SB et al (2008) Effectiveness of weight management programs in children and adolescents. Evid Rep Technol Assess 170:1–308

Rajmil L, Bel J, Clofent R et al (2017) Clinical interventions in overweight and obesity: a systematic literature review 2009–2014. Anales de Pediatría 86:197–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anpede.2016.03.013

Ramalho SM, Silva CB, Pinto-Bastos A, Conceição E (2016) New technology in the assessment and treatment of obesity. In: Ahmad S, Imam S (eds) Obesity, Springer, Cham, pp 257–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19821-7_20

Barak A, Hen L, Boniel-Nissim M, Shapira N (2008) A comprehensive review and a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of Internet-based psychotherapeutic interventions. J Technol Hum Serv 26:109–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228830802094429

Park BK, Nahm ES, Rogers VE (2016) Development of a Teen-friendly health education program on Facebook: lessons learned. J Pediatr Health Care 30:197–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2015.06.011

Ruotsalainen H, Kyngas H, Tammelin T et al (2015) Effectiveness of Facebook-delivered lifestyle counselling and physical activity self-monitoring on physical activity and body mass index in overweight and obese adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Nurs Res Pract. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/159205

Napolitano M, Hayes S, Bennett GG et al (2013) Using Facebook and text messaging to deliver a weight loss program to college students. Obesity 21:25–31. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2012.107

Merchant G, Weibel N, Patrick K et al (2014) Click like to change your behavior: a mixed methods study of college students’ exposure to and engagement with Facebook content designed for weight loss. J Med Internet Res 16:e158. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3267

Lenhart A, Purcell K, Smith A, Zickuhr K (2010) Social media and mobile internet use among teens and young adults. PEW Res Cent. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed8000717

Neve M, Morgan PJ, Jones PR, Collins CE (2010) Effectiveness of web-based interventions in achieving weight loss and weight loss maintenance in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Obes Rev 11:306–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00646.x

Kaisari P, Yannakoulia M, Panagiotakos DB (2013) Eating frequency and overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 131:958–967. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3241

Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Perry C, Story M (2003) Correlates of fruit and vegetable intake among adolescents: findings from Project EAT. Prev Med (Baltim) 37:198–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00114-2

Loth KA, MacLehose RF, Larson N et al (2016) Food availability, modeling and restriction: how are these different aspects of the family eating environment related to adolescent dietary intake? Appetite 96:80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.08.026

Eriksson I, Unden AL, Elofsson S (2001) Self-rated health. Comparisons between three different measures. Results from a population study. Int J Epidemiol 30:326–333. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/30.2.326

Maloney MJ, McGuire JB, Daniels SR (1988) Reliability testing of a children’s version of the eating attitude test. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27:541–543. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-198809000-00004

Teixeira M, Pereira A, Saraiva J et al (2012) Portuguese validation of the children’s eating attitudes test. Revista de Psiquiatria Clínica 39:189–193. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-60832012000600002

Tylka TL, Kroon Van Diest AM (2013) The Intuitive Eating Scale-2: item refinement and psychometric evaluation with college women and men. J Couns Psychol 60:137–153. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030893

Duarte C, Pinto-Gouveia J, Mendes A (2016) Psychometric properties of the Intuitive Eating Scale-2 and association with binge eating symptoms in a Portuguese community sample. Int J Psychol Psychol Ther 16:329–341

Lemoine JE, Konradsen H, Lunde Jensen A et al (2018) Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Body Appreciation Scale-2 among adolescents and young adults in Danish, Portuguese, and Swedish. Body Image 26:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.04.004

Conceição E, Mitchell JE, Machado PP et al (2017) Repetitive eating questionnaire [Rep (eat)-Q]: enlightening the concept of grazing and psychometric properties in a Portuguese sample. Appetite 117:351–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.07.012

Saint-Maurice PF, Welk GJ (2014) Web-based assessments of physical activity in youth: considerations for design and scale calibration. J Med Internet Res 16:e269. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3626

Whiteside SP, Lynam D, Miller J, Reynolds S (2005) Validation of the UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale: a four factor model of impulsivity. Eur J Personal 19:559–574. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.556

Gloster AT, Rhoades HM, Novy D et al (2008) Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 in older primary care patients. J Affect Disord 110:248–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.01.023

Leal I, Antunes R, Passos T et al (2009) Estudo da Escala de Depressão Ansiedade e Stresse para Crianças (EADS-C). Psicol saúde doenças 10:277.284

Lima L, Guerra MP, Lemos M (2009) Adaptação da escala genérica do Inventário Pediátrico de Qualidade de Vida—Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4. 0—PedsQL, a uma população portuguesa. Rev Port Saude Publica 8:83–96. http://hdl.handle.net/10216/15721

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2007) Using multivariate statistics, 5th edn. Allyn and Bacon, New York

Goldschmidt AB, Aspen VP, Sinton MM et al (2008) Disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in overweight youth. Obesity 16:257–264. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.48

Hayes JF, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Karam AM et al (2018) Disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in youth with overweight and obesity: implications for treatment. Curr Obes Rep 7:235–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-018-0316-9

Neumark-Sztainer DR, Wall MM, Haines JI et al (2007) Shared risk and protective factors for overweight and disordered eating in adolescents. Am J Prev Med 33:359–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMEPRE.2007.07.031

Rancourt D, McCullough MB (2015) Overlap in eating disorders and obesity in adolescence. Curr Diabetes Rep 15:e78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-015-0645-y

Rankin J, Matthews L, Cobley S et al (2016) Psychological consequences of childhood obesity: psychiatric comorbidity and prevention. Adolesc Health Med Ther 7:125–146. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S101631

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia/Foundation for Science and Technology through a European Union COMPETE program Grants to Eva Conceição (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-028209 and IF/01219/2014) and doctoral scholarship (SFRH/BD/104182/2014) to Sofia Ramalho. This work was conducted at Psychology Research Centre (UID/PSI/01662/2013), University of Minho and supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology and the Portuguese Ministry of Science, Technology, and Higher Education through national funds and co-financed by FEDER through COMPETE2020 under the PT2020 Partnership Agreement (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-007653).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the university ethics review board and by the ethical committees from the hospital centers involved [São João Hospital Center (CHSJ), Oporto Hospital Center—Northern Maternal and Child Center (CMIN)].

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants’ parents/caregivers.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ramalho, S., Saint-Maurice, P.F., Silva, D. et al. APOLO-Teens, a web-based intervention for treatment-seeking adolescents with overweight or obesity: study protocol and baseline characterization of a Portuguese sample. Eat Weight Disord 25, 453–463 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0623-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0623-x