Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to examine the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Experience of Caregiving Inventory (ECI-S), which is designed to assess the caregiver’s appraisal of the impact of caring for a relative with a serious mental illness.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 320 caregivers of a relative with an eating disorder to examine: (a) descriptive statistics; (b) internal consistency reliability; (c) the fit of the original ten-factor structure of the ECI through exploratory factor analysis, using a semi-confirmatory approach, for each subscale individually, and (d) concurrent validity. A total of 307 caregivers completed the scale.

Results

Reliability of the ECI subscales scores was acceptable (α = 0.63–0.89). Results replicated the original ten-factor structure of the instrument. The concurrent validity was supported by correlations of the ECI-negative subscale with psychological distress (GHQ-12, 0.43), and with depression and anxiety (HADS, 0.48 and 0.49, respectively).

Conclusions

The Spanish version of the ECI (ECI-S) demonstrated good psychometric properties in terms of validity and reliability that were similar to the original version. It is an acceptable and valid instrument for assessing the impact on family members of caring for a relative with an eating disorder and can be recommended for use in clinical settings in Spain.

Level of evidence

Level V, cross-sectional descriptive study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Family members caring for a relative with a mental illness may experience increased difficulties and stress as a result of their caregiving role [1, 2]. One concept that has received a great deal of attention in the larger caregiving literature is that of caregiver burden, which has been reported amongst those caring for a loved one with dementia [3], schizophrenia [1], bipolar disorder [4], eating disorders [5] and cancer [6], among others. Burden is usually considered to be a multidimensional construct which may include physical, emotional, and social problems associated with the caregiving role [7]. However, a great deal of debate has arisen regarding the ideal way to operationalize and assesses this construct [8].

A systematic review published in 2003 that examined the psychometric properties of several instruments developed to assess caregiver burden [9] identified the Experience of Caregiving Inventory (ECI) [10] as one of most valid and reliable self-report instruments available to measure this construct. This questionnaire introduced a new approach to caregiving by rejecting the notion of burden and instead assesses the experience of caring for a relative with a serious mental illness within a ‘stress–appraisal–coping’ model [11] by evaluating the caregiver’s appraisal of how they were impacted by the caregiving role. Furthermore, this instrument takes into consideration positive aspects of the caregiving role, which is an often overlooked aspect of caregiving that is gaining increasing attention in caregiver research [12].

The ECI is comprised of 66 items grouped into two dimensions. The ECI-negative subscale is composed of eight factors (52 items, total score ranges from 0 to 208) that include: (1) difficult behaviors; (2) negative symptoms; (3) stigma; (4) problems with services; (5) effects on family; (6) need to backup; (4) dependency; and (8) loss. The ECI-positive subscale is made up of two factors (14 items, total score ranges from 0 to 56): (1) positive personal experiences and (2) good relationship with the patient. Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (nearly always). The validation study of the original instrument [10] found that all subscales presented satisfactory reliability indexes (alphas ranging from 0.74 to 0.91), and that the ECI-negative explained 24% of the variance in psychological distress, thus providing robust evidence for its construct validity.

To date, the ECI has been translated into four languages: Italian [13], Chinese [14] Portuguese [15], and Hindi [16]. The Italian cross-cultural study compared 95 Italian caregivers of relatives with a psychotic disorder and 69 caregivers from London [13]. The reliability of the Italian ECI subscales was good, ranging from 0.71 to 0.86, and the external validity between the ECI-negative and the GHQ-12 score was moderate (r = 0.47). Regarding the Chinese study, the ECI was examined among 129 caregivers in schizophrenia presenting good positive and negative appraisals for the reliability index (0.85 and 0.91, respectively). However, the structural dimension varied significantly from the original ECI and did not replicate it, using a principal component analysis with Varimax rotation as that applied by the original author. The correlation coefficient between the ECI-negative and the GHQ-12 score was moderate (r = 0.43) [14]. The Portuguese study translated and examined 75 first-episode-psychosis caregivers’ appraisal at the initial phase of treatment in Brasil [15], only reliability was obtained with an ECI-negative score of 0.94 and an ECI-positive score of 0.81. Finally, the Indian study presented a cross-sectional study of 50 caregivers in schizophrenia, the authors only translated the instrument into Hindi [16]. Thus, to date, a Spanish version of the ECI has not been translated or validated. Validation studies in additional cultures are needed to further explore the reliability, validity and cross-cultural adequacy of this instrument.

The main objective of the present study was to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Experience of Caregiving Inventory (ECI-S) amongst a group of caregivers of a patient with an eating disorder. The specific aims of the study included: (a) to examine descriptive statistics; (b) to test the fit of the original factor structure of the ECI on the Spanish version of the instrument via exploratory factor analysis (EFA), (c) to explore the internal consistency reliability of the ECI-S total score and subscale scores, and (d) to assess the concurrent validity of the scale.

Methods

Participants

A total of 307 caregivers of 209 patients with an eating disorder were included. Of these caregivers, 206 were primary caregivers, 180 of which were female (87.4%), and 101 were secondary caregivers, 13 of which were female (12.8%). Secondary caregivers were included due to the fact that pairwise comparisons t tests revealed significant differences between their scores and those of the primary caregivers on measures of general caregiving experience and psychological distress. The participants were recruited from the Eating Disorders Unit at Marques of Valdecilla University Hospital (n = 60), the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Service at Niño Jesus University Hospital (n = 180) and from the Spanish Eating Disorders Association for Caregivers (ADANER) (n = 80). ADANER is a national network of families that provides information, education, and support groups led by expert caregivers.

A cross-sectional and descriptive study using self-report questionnaires was carried out. All the caregivers recruited from the hospitals had a relative who was previously diagnosed with an eating disorder by a mental health professional at the respective hospital, according to DSM-IV-TR criteria [17]. All of these patients received the appropriate multidisciplinary treatment in specialized eating disorder units. The ill relatives of the caregivers recruited from ADANER had also previously received an eating disorder diagnosis and the majority had received specific treatment for their eating disorder through the Spanish public health care system.

Instruments

The following instruments were chosen to assess psychological distress, anxiety and depression among caregivers.

Sociodemographic variables and patients’ clinical variables

Caregivers completed a questionnaire to collect information such as gender, age, educational level, marital status, and employment status. The clinical variables of the patients included gender, age, diagnosis, age of first diagnosis, treatment and duration of the illness. These clinical variables were obtained through the patient’s medical records, with the exception of the ADANER association where the diagnosis was reported by the caregivers themselves.

The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12)

[18, 19] was used to measure the caregivers’ level of psychological distress. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 to 3) with total scores ranging from 0 to 36. The GHQ has shown high internal reliability (α = 0.91) and high validity. The Spanish version has been employed with general adult samples [20], showing a satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76) and adequate external validity. Higher scores indicate increased psychological distress.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

[21, 22] is designed to detect the presence and severity of anxiety and depression. It consists of 14 questions, 7 for anxiety and 7 for depression, assessed on a 4-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 to 3). Previous research has shown an acceptable Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.86 for each of the two subscales. The Spanish version was validated in a general population sample with similar reliability values [23]. Furthermore, it has demonstrated high concurrent validity through correlations between the depression subscale and the Beck Depression Inventory, and the anxiety subscale with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory [22].

Procedure

Participants were recruited over a period of 2 years (from January 2007 to January 2009). Caregivers were recruited from consecutive admissions or outpatient services at the hospitals and from ADANER. Non-probability sampling was used [24]. Family members were provided with an information sheet about the study, a consent form, and the questionnaires. To be eligible for this study, the caregivers had to be currently living with, or caring for, a family member with an eating disorder. Participation was voluntary and no incentives were offered for participation. The hospitals granted ethical committee approval for this study (Reference Number: R-009/10).

Of the 320 relatives that were collected, only 307 caregivers were included in the statistical analyses, due to the exclusion of caregivers who did not properly complete the ECI questionnaire (n = 13; 4.2% of the sample had three or more incomplete items).

Translation

The translation of the ECI was carried out using a back translation procedure following the international guidelines proposed by Muñiz and Bartram [25]: (a) two independent translations were made of the original English version to Spanish by two expert translators with knowledge of psychology and psychopathology; (b) these versions were compared to identify the points of disagreement between them and were consolidated into one version; (c) this version was translated back into English by another expert translator; (d) the direct and back-translated versions were compared by a qualified translator, as well as the researchers, to verify the conceptual and semantic equivalence; (e) after this, the scale was administered to ten caregivers from ADANER to identify terminology that may be subject to confusion and as well as possible difficulties in the instrument’s application; and (f), pertinent adjustments were made to the wording of the questionnaire. The definitive version that was generated is presented in this article (see supplementary material file). The translation of the instrument was approved by the authors of the original English version of the instrument.

Statistical analysis

Data from the same family have been analyzed separately by classifying into primary and secondary caregivers (101 were secondary caregivers) as if they were independent samples or not, and Mann–Whitney test-yielded differences were statistically significant between the two samples (p < 0.01), so both parents were included as independent informants. A series of analyses were conducted to test the psychometric properties of the ECI scale using the statistical software packages SPSS version 19.0 [26] and FACTOR 9.2 [27, 28]. The FACTOR program provides a semi-confirmatory approach to the analysis of an instrument's structure and its use has been recommended to improve EFA practices [29].

Descriptive statistics and reliability

Descriptive statistics for the ECI subscales scores were examined. To determine the internal consistency reliability of the ECI total scale and subscale scores, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated and item-total correlations were examined. For the alpha to be acceptable it must be at or above 0.70 and item-total correlations should exceed the minimum acceptable level of 0.30 [30].

Factor structure

An initial confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the ECI-S was carried out. However, a CFA of a model with such a large number of items and latent factors was very complex. Indications regarding the number of underlying factors for the ECI-S total scores were obtained from a parallel analysis (PA) based on minimum rank factor analysis [31], minimum average partial (MAP) test [32], and HULL [33] yielding contradictory indications of retaining 5, 3 and 1 factors, respectively.

Thus, to examine the underlying dimensional structure of the ECI-S scores, exploratory factor analyses (EFA) were conducted, one per subscale. That is, we examined whether the ECI-S subscales were essentially one-dimensional taking into account the information provided by the parallel analyses [31]. In terms of the univariate descriptive statistics, several items had values of absolute skewness or kurtosis greater than 1, and the tests of multivariate kurtosis were significant. EFA used the polychoric correlation matrix, which is particularly robust for Likert-type items [34, 35]. The method for factor extraction was unweighted least squares (ULS), which does not require the assumption of normality to be met. Other indicators provided by the program FACTOR were examined for each subscale individually, such as the suitability of the correlation matrix by Bartlett’s Sphericity test and Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) index, model data fit by Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), and root mean square of residuals (RMSR). We considered GFI values appropriate if they were above 0.95 [36]. The Pearson correlations between the ten subscales of the ECI-S were also analyzed.

Concurrent validity

Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests were first carried out to check for the homogeneity of the variance and normal distribution of the data and based on the results, non-parametric statistical tests were used. The concurrent validity was examined using Spearman correlations between the subscale scores of the ECI-S and psychological distress (GHQ-12), and levels of anxiety and depression (HADS). Concurrent validity was also explored by examining the association between patients’ age, type of diagnosis, duration of illness, and the ECI-S-negative and ECI-S-positive scores. Cohen [37] suggested the following guidelines to interpret correlations: 0.10–0.29 as small, 0.30–0.49 as moderate, and higher than 0.50 as large.

Results

Sample characteristics

The mean age of the caregivers was 48.8 years (SD = 7.3; range: 20–75). The majority of the caregivers were married or living together (n = 260; 85%), 12% were divorced or separated (n = 37) and 3% were widowed (n = 10). A total of 173 caregivers (58.4%) reported secondary school as their highest level of education, and 123 (41.6%) had completed higher education. Most of the caregivers (n = 298; 97%) were parents, and 3% were sisters or spouses. A total of 198 (65.3%) had a full- or part-time job. The majority of the caregivers (90%) were currently living with the patient. Of the 202 patients, the majority (94%) were female. Their mean age was 19.3 years (SD = 5.5; range 12–34). A total of 146 patients had a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa (70%) and 63 had bulimia nervosa (30%). The mean duration of their illnesses was 4 years (SD = 4.6) and the mean numbers of months they had been in treatment was 12.2 (SD = 12.0). The majority of the patients were currently in treatment (85.4%).

Descriptive statistics and reliability

Distribution of the means and standard deviations of the items for the subscales and the two dimensions and the corrected item-total correlations ranges are shown in Table 1. The mean scores ranged from 0.41 (SD = 0.88; Item 42) to 3.54 (SD = 0.82; Item 4). The corrected item-total correlation values of items for the corresponding subscales were above the 0.30 criterion in all cases, with the exception of item 4 (rciX = 0.17) and item 41 (rciX = 0.27). The internal consistency reliability of the ECI-S total score was high (α = 0.93) and was adequate for the subscales scores as well.

Factor structure

The internal structure was examined for each subscale. The Bartlett’s Sphericity tests (all p < 0.001) and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin index values (KMO ranging from 0.68 to 0.88), supported the factorability of the data matrices (Table 1).

All of the parallel analyses applied to the items, comprising each of the ten ECI-S subscales, suggested one-factor solutions, thus supporting their unidimensionality. Total variance explained by these extracted single-factors ranged from 37.72% (“need to backup”) to 59.68% (“negative symptoms”). The factor loadings for the one-factor solutions, shown in Table 1, were above 0.40 in all cases except for item 65 (0.37) and item 4 (0.07). Values of GFI showed a good fit of data for the ten subscales (from 0.95 to 1.00). RMSR values ranged from 0.035 to 0.129. Although RMSR values for five subscales (“problems with services,” “effects on family,” “loss,”“stigma,” and “negative symptoms”) were somewhat high, with respect to residuals for these subscales, means were close to zero (range: 0.0001–0.0020) and variances were low (range: 0.0093–.0167). Overall, the data supported the unidimensionality of each subscale and the statistics indicated a reasonable fit.

Scoring the ECI-S scale

Given that the original items and ten-factor structure were maintained, the ECI-S scale is scored in the same way as the original scale. The mean ECI-S-negative total for the 307 caregivers was 84.2 (SD = 31.0; Range: 0–208) and the ECI-S-positive total score was 29.5 (SD = 9.6; Range 0–56).

Subscale intercorrelations

The correlations between the factors ranged from 0.23 to 0.71 (p < 0.01) and are presented in Table 2. Most of the correlations between factors ranged from moderate to large. Table 3 demonstrates that all eight factors of the ECI-S-negative were highly correlated with the ECI-S negative score (rs = 0.59−0.77, p < 0.01). The ECI-S-positive dimension score was highly correlated with the two factors comprising this dimension, “positive personal experiences” and “good aspects of relationship” (0.90 and 0.79, respectively, p < 0.01). Moreover, the association between the positive and negative dimensions was low (rs = 0.26, p < 0.01), indicating they measure different constructs of the caregiving experience.

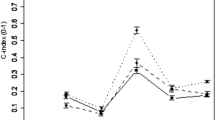

Concurrent validity

Concurrent validity was determined according to the correlations between the ECI-S-negative total and ECI-S-positive total, and the GHQ-12 and HADS subscales (Table 3). The highest positive correlation for the ECI-S negative dimension occurred with anxiety (rs = 0.49, p < 0.01), and depression (rs = 0.48, p < 0.01). The positive dimension of the ECI-S did not correlate with the overall GHQ or HADS scores. Regarding the subscales of ECI-S, the highest positive correlation for psychological distress (measured by the GHQ-12) was with the “difficult behavior” scale (rs = 0.40, p < 0.01). The highest correlation with the HADS depression subscale occurred with the “dependency” scale (rs = 0.45, p < 0.01), whereas the highest correlation with the HADS anxiety subscale occurred with “loss” and “difficult behavior” (rs = 0.44, p < 0.01).

Contrary to our hypotheses, there were no associations between the patients’ age, type of diagnosis or duration of illness, and the ECI-S negative total or ECI-S positive total score. Only a small negative correlation was found between caregivers’ age and the ECI-S negative (rs = − 0.21, p < 0.05).

Discussion

Cross-cultural adaptation of instruments that allow for the assessment of how caretakers are affected by the task of caring for a loved one with a mental illness is essential. Such instruments provide important information that can aid in the development and evaluation of caregiver interventions aimed at lessening the negative consequences of the caregiving experience. The primary aim of the current study was to validate the Experience of Caregiving Inventory (ECI) in a sample of Spanish caregivers of patients with an eating disorder. An examination of the appropriateness of the structure proposed by the authors of the original instrument [10] amongst a sample of 307 caregivers in Spain revealed that the ten-factor solution is appropriate for the ECI-S as it presents fit values that are consistent with standards of acceptance. An additional benefit of the ECI in particular is its ability to shed light on possible benefits that caregivers may take away from their caretaking role.

The ECI is a well-known instrument that assesses the experience of caregivers of patients with psychiatric conditions with a protracted course. However, the majority of the studies have used this instrument with caregivers of patients with schizophrenia [13, 15], or a heterogeneous group of caregivers of patients with a severe mental illness [14]. Unlike these studies, the current study employed a sample of caregivers of patients who had all received a diagnosis of an eating disorder. Another strength of the current study is that, in comparison with the other studies assessing the factor structure of the ECI, it used a notably larger sample size, which was acceptable for this type of analysis.

The current study is further strengthened by the appropriate levels of internal consistency that were observed. The ECI-S-negative had an alpha of 0.93, whereas the ECI-S-positive presented an alpha of 0.84. These values are similar, or slightly higher, than the other published versions of the ECI [10, 13,14,15]. A total of eight subscales presented alphas that were considerably greater than 0.70, which is comparable to the original version and to the Italian and Portuguese versions [10, 13, 15]. However, consistent with the Chinese version [14], we obtained coefficients that were lower than 0.70 for the “need to backup” (0.58) and “dependency” (0.69) subscales. The low alphas for these two subscales may be explained by the different sociocultural context of the Spanish sample. Young adults in Spain tend to remain at their parent’s home for longer than in other cultures, and in our sample the mean age of the patients was 19 years and 90% of them were living at home. Therefore, this kind of “dependence” and “need to backup” may not have been perceived in the same way by their caregiver, and may have not been appraised as a negative experience, but rather a part of normal parenting within most Spanish families.

Item-total subscale correlations showed that the majority of the items for each of the subscales were highly correlated, and with the exception of two items, were above the recommended minimum of 0.30. In regards to the factor loadings, only two items were below the recommended level of 0.40. Given the relevance of this instrument when applied to families of patients with varying mental disorders, we decided to maintain a conservative attitude in retaining the items and the original factors. Exhaustive data and factor loadings for each item can be requested from the first author.

In regard to external validity, a moderate correlation was observed between the ECI-S negative and the total GHQ-12 and the HADS anxiety and depression, indicating higher psychological distress in caregivers who reported more negative aspects of the caregiving experience, a finding which mirrors those of previous studies [10, 13,14,15,16]. Also similar to previous research [13,14,15], the positive dimension of the ECI-S did not correlate with the overall GHQ or HADS scores.

In the present study, a low positive correlation between the ECI-S negative and ECI-S positive was found, which suggests that the caregiving experience has two clearly separated dimensions. This finding is in contrast to the study by Aggarwal et al. [16] which found a correlation of 0.54 between both dimensions. Furthermore, a small negative correlation was observed between caregivers´ age and the ECI-S negative, which suggests that older caregivers may be impacted less by the caregiving experience.

Our findings regarding the caregiving experience in eating disorders appear to be similar to studies of other psychiatric conditions with a protracted course. The means of the ECI-S negative (84.2) and positive (29.5) subscales are similar to findings by the instrument’s original authors [10] and those of the Brazilian sample [15]. However, they are in contrast to findings from other studies which reported lower scores for both dimensions [13, 14, 16]. Although the sociodemographic profile of caregivers and patients are not quite comparable among samples, it seems that the ECI instrument is capable of describing the general caregiving experience in eating disorders. Likewise, very few have been very limited research exploring caregivers’ burden in eating disorders [38,39,40].

Limitations

The current study is not without its limitations. First, the results of this study require replication, ideally with a larger and more diverse sample of caregivers. Second, additional attention should also be given to assessing test–retest reliability or discriminant validity that are two properties that were not assessed in the current study. Future studies should complement the data with family interviews and data collected from the patients, such as their perception of burden, so as to overcome the limitation of using only questionnaires. The majority of diagnoses and clinical variables (e.g., illness duration) were established by medical reports, thus limiting the potential bias related to this data to only the ADANER sample. Furthermore, all of the patients who were relatives of the ADANER members had been diagnosed and had received (or were receiving) treatment for their eating disorder. Future studies should continue assessing the factor structure of the Spanish version of the ECI.

Implications and conclusions

One of the crucial research aims in clinical psychology is to collect empirical findings on the psychometric properties of psychological assessment and/or screening instruments. The results from this study on the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the ECI suggest that it is a valid tool for assessing the general caregiving experience in eating disorders. The ability to properly assess the key patient–caregiver variables related to the maintenance of eating disorders is critical to decreasing the negative physical and psychological health outcomes for caregivers and patients alike [41]. Appropriately tailored interventions can improve the health and well-being of both caregiver and patient [42].

References

Caqueo-Urízar A, Miranda-Castillo C, Giráldez SL, Maturana S-lL, Pérez MR, Tapia FM (2014) An updated review on burden on caregivers of schizophrenia patients. Psicothema 26(2):235–243. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2013.86

Anastasiadou D, Medina-Pradas C, Sepulveda AR, Treasure J (2014) A systematic review of family caregiving in eating disorders. Eat Behav 15(3):464–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.06.001

Chiao CY, Wu HS, Hsiao CY (2015) Caregiver burden for informal caregivers of patients with dementia: a systematic review. Int Nurs Rev 62(3):340–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12194

Pompili M, Harnic D, Gonda X, Forte A, Dominici G, Innamorati M, Fountoulakis KN, Serafini G, Sher L, Janiri L (2014) Impact of living with bipolar patients: making sense of caregivers’ burden. World J Psychiatry 4(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v4.i1.1

Anastasiadou D, Sepulveda AR, Sanchez JC, Parks M, Alvarez T, Graell M (2016) Family functioning and quality of life among families in eating disorders: a comparison with substance-related disorders and healthy controls. Euro Eat Disord Rev 24(4):294–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2440

Hsu T, Loscalzo M, Ramani R, Forman S, Popplewell L, Clark K, Katheria V, Feng T, Strowbridge R, Rinehart R (2014) Factors associated with high burden in caregivers of older adults with cancer. Cancer 120(18):2927–2935. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28765

Platt S (1985) Measuring the burden of psychiatric illness on the family: An evaluation of some rating scales. Psychol Med 15(02):383–393. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700023680

Moller T, Gudde CB, Folden GE, Linaker OM (2009) The experience of caring in relatives to patients with serious mental illness: Gender differences, health and functioning. Scand J Caring Sci 23(1):153–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00605.x

Reine G, Lancon C, Simeoni MC, Duplan S, Auquier P (2003) Caregiver burden in relatives of persons with schizophrenia: An overview of measure instruments. L’Encephale 29(2):137–147

Szmukler GI, Burgess P, Herrman H, Benson A, Colusa S, Bloch S (1996) Caring for relatives with serious mental illness: the development of the experience of caregiving inventory. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 31(3–4):137–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00785760

Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1984) Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer, New York

Lloyd J, Patterson T, Muers J (2016) The positive aspects of caregiving in dementia: A critical review of the qualitative literature. Dementia (Lond Engl) 15(6):1534–1561. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301214564792

Tarricone I, Leese M, Szmukler GI, Bassi M, Berardi D (2006) The experience of carers of patients with severe mental illness: a comparison between London and Bologna. Euro Psychiatry 21(2):93–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.09.012

Lau D, Pang A (2007) Validation of the Chinese version of experience of caregiving inventory in caregivers of persons suffering from severe mental disorders. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 17(1):24–32

de Araújo Jorge R, Chaves A (2012) The Experience of Caregiving Inventory for first-episode psychosis caregivers: Validation of the Brazilian version. Schizophr Res 138(2–3):274–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2012.03.014

Aggarwal M, Avasthi A, Kumar S, Grover S (2011) Experience of caregiving in schizophrenia: a study from India. Int J Soc Psychiatry 57(3):224–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764009352822

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-IV-TR fourth edition (text revision). American Psychiatric Association, Washington

Lobo A, Muñoz P (1996) Versiones en lengua española validadas [Validated versions in the Spanish language]. Cuestionario de Salud General GHQ [General Health Questionnaire] Guía para el usuario de las distintas versiones Barcelona: Masson

Goldberg DP, Williams PA (1978) User’s guide to The General Health Questionnaire. NFER Nelson, Windsor

Sanchez-Lopez MP, Dresch V (2008) The 12-Item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12): reliability, external validity and factor structure in the Spanish population. Psicothema 20(4):839–843

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

Quintana JM, Padierna A, Esteban C, Arostegui I, Bilbao A, Ruiz I (2003) Evaluation of the psychometric characteristics of the Spanish version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 107(3):216–221. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00062.x

Terol M, López-Roig S, Rodríguez-Marín J, Martí-Aragón M, Pastor M, Reig M (2007) Propiedades psicométricas de La Escala Hospitalaria de Ansiedad y Depresión (HADS) en población española [Psychometric properties of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in a Spanish population]. Ansiedad y Estrés 13:163–176

Hernández Sampieri R, Fernández Collado C, Baptista Lucio P (2003) Metodología de la investigación [Research Methodology], vol 707. McGraw-Hill, México

Muñiz J, Bartram D (2007) Improving international tests and testing. Eur Psychol 12(3):206–219. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.12.3.206

IBM (2010) Statistical package for the social sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics) for Windows, release 19.0. IBM SPSS Statistics, Chicago

Lorenzo-Seva U, Ferrando PJ (2006) FACTOR: A computer program to fit the exploratory factor analysis model. Behav Res Methods 38(1):88–91. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03192753

Lorenzo-Seva U, Ferrando PJ (2013) FACTOR 9.2: a comprehensive program for fitting exploratory and semiconfirmatory factor analysis and IRT models. Appl Psychol Meas 37(6):497–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146621613487794

Baglin J (2014) Improving your exploratory factor analysis for ordinal data: a demonstration using FACTOR. Pract Assess Res Eval 19(5):1–15

Nunnally J (1978) Psychometric methods. McGraw-Hill, New York

Timmerman ME, Lorenzo-Seva U (2011) Dimensionality assessment of ordered polytomous items with parallel analysis. Psychol Methods 16(2):209–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023353

Velicer WF (1976) Determining the number of components from the matrix of partial correlations. Psychometrika 41(3):321–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02293557

Lorenzo-Seva U, Timmerman ME, Kiers HA (2011) The Hull method for selecting the number of common factors. Multivar Behav Res 46(2):340–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2011.564527

Ferrando PJ, Anguiano-Carrasco C (2010) El análisis factorial como técnica de investigación en psicología [Factorial analysis as a research technique in psychology}. Papeles del Psicólogo 31(1):18–33

Izquierdo Alfaro I, Olea Díaz J, Abad FJ (2014) Exploratory factor analysis in validation studies: Uses and recommendations. Psicothema 26(3):395–400. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2013.349

Lt Hu, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model A Multidisci J 6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2 edn. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, Hilsdale

Padierna A, Martin J, Aguirre U, Gonzalez N, Muñoz P, Quintana JM (2013) Burden of caregiving amongst family caregivers of patients with eating disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 48:151–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0525-6

Winn S, Perkins S, Walwyn R, Schmidt U, Eisler I, Treasure J… (2006) Predictors of mental health problems and negative caregiving experiences in carers of adolescents with bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 40:171–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20347

Treasure J, Murphy T, Szmukler G, Todd G, Gavan K, Joyce J (2001) The experience of caregiving for severe mental illness: A comparison between anorexia nervosa and psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 36:343–347

Schmidt U, Treasure J (2006) Anorexia nervosa: valued and visible. A cognitive-interpersonal maintenance model and its implications for research and practice. Br J Clin Psychol 45(3):343–366. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X53902

Hibbs R, Rhind C, Leppanen J, Treasure J (2015) Interventions for caregivers of someone with an eating disorder: a META-analysis. Int J Eat Disord 48(4):349–361. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22298

Acknowledgements

Dr. Sepúlveda has a postdoctoral Ramon and Cajal scholarship from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (RYC-2009-05092) as well as a project funding from the same Ministry (PSI2011-23127). M. Graell is a member of the Spanish Psychiatric Research Network (CIBERSAM). We thank Dr.A. del Barrio from Marques of Valdecilla University Hospital that helped with the recruitment. We would like to thank Jeff Barrera and for his help with revising the final version. Finally, we would also like to express our gratitude to the caregivers who took part in this study.

Funding

Dr. Sepúlveda has a postdoctoral Ramon and Cajal scholarship from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (RYC-2009-05092) as well as a project funding from the same Ministry (PSI2011-23127).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sepulveda, A.R., Almendros, C., Berbel, E. et al. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Experience of Caregiving Inventory (ECI) among caregivers of individuals with an eating disorder. Eat Weight Disord 25, 299–307 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0587-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0587-x