Abstract

The relationship between self-compassion and well-being and health (e.g. a lower proneness for eating-related disturbances) is well stressed in the literature. However, the specific contribution of self-compassionate attributes, actions, and body compassion remains scarcely studied. The main aim of the present study was to examine whether the link between self-compassionate attributes and disordered eating attitudes and behaviours is mediated by self-compassionate actions and body compassion, in a sample of 299 Portuguese women from the general population. The tested model explained 44% of eating psychopathology’s variance and presented excellent fit indices. The most interesting contribution of this study was the suggestion that the ability to act in accordance with self-compassionate attributes is associated with higher levels of body compassion, that is, an attitude of appreciation, acceptance, warmth toward body-related thoughts, perceptions and feelings, which reflects in a lower susceptibility to adopt disordered eating attitudes and behaviours. These results seem to offer an important contribution for research and clinical practice by supporting the importance of including strategies to develop self-compassionate skills and body compassion competencies in prevention and treatment programs in the area of eating psychopathology.

Level of evidence Level III, evidence obtained from a well-designed cohort.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The interest on the benefits of compassion has grown rapidly during the last decade (e.g. [1]). The concept of compassion is derived from the Buddhist traditions, and is defined as a sensitivity to suffering of the self and of others with a commitment to engage with suffering and prevent it (e.g. [2]).

From an evolutionary approach, compassion is considered an advantageous competency that evolved from attachment and caring motivation and responses (e.g. [3]). According to this perspective, compassion is conceptualized as a combination of motives, emotions, thoughts, and behaviours, and involves two dimensions: compassionate attributes (i.e. an intentional sensitivity to suffering, ability to tolerate distress in an accepting and nonjudgmental way, and motivation to engage with suffering) and compassionate actions (i.e. motivation and commitment to take helpful actions to prevent or deal with one’s self and others’ distress, in a kind, supportive and accepting manner) [1, 3,4,5]. Additionally, when compassion is self-directed, it is called self-compassion [6, 7].

Self-compassion involves the ability to experience feelings of care and kindness toward oneself in instances of pain, and perceived failure, mistakes and inadequacies. This skill also involves the adoption of an understanding and nonjudgmental attitude towards one’s difficulties, and the recognition of these difficulties as part of the larger human experience [6,7,8]. A body of evidence has shown that self-compassion is positively associated with many aspects of healthy psychological functioning, such as positive affect, well-being, adaptive coping and social connectedness [6, 7, 9]. Also, self-compassion is negatively related to a variety of mental health difficulties (e.g. anxiety, depression, neurotic perfectionism, rumination and self-criticism) [7, 10,11,12]. Particularly in the areas of body image and eating-related difficulties, several studies suggested that self-compassion may have a protective role in women (e.g. [13,14,15,16,17]). In fact, empirical evidences have demonstrated that self-compassionate abilities significantly buffered the impact of high BMI and body dissatisfaction on the severity of disordered eating (e.g. [18, 19]). In a more recent study, Marta-Simões and colleagues [20] revealed that self-compassion is linked to an attitude of appreciation, acceptance and respect for one’s own body, regardless of its appearance (i.e. body appreciation). Also, Máximo, Ferreira and Marta-Simões [21] revealed that women who present a greater ability to engage in actions that are congruent with self-compassionate attributes tend to experience higher levels of body appreciation and a lower tendency to display disordered eating symptoms.

Notwithstanding the extensive research on compassion, the study of compassionate competencies specifically focused on the domain of body image remains scarce. Recently, a measure that allows the assessment of body compassion was developed (Body Compassion Scale [22]). The body compassion construct encompasses two multidimensional concepts: body image that refers to one’s body-related perceptions and attitudes [23, 24] and self-compassion [6]. In accordance with Altman and colleagues [22], body compassion is a new construct that may contribute to the understanding of how individuals relate to their bodily perceived inadequacies, flaws or limitations, and inform the development of novel treatment approaches. Body compassion, as assessed by the Body Compassion Scale, comprises three factors: (1) defusion (i.e. an attitude of decentering or mindfulness, as opposed to an attitude of over-identification with one’s body imperfections, limitations or inadequacies); (2) common humanity (i.e. the ability to understand one’s negative aspects of body image as part of the larger human experience, instead of assuming an isolating or shaming perspective) and (3) acceptance (i.e. acceptance of body-related painful thoughts, perceptions, and feelings in a generous and kind manner, instead of adopting a self-judgmental attitude) [22].

Although body compassion is a fresh construct, existing data appear to be promising. Altman and colleagues [22] emphasized that higher levels of body compassion were positively associated with body image flexibility and positive affect, and negatively related to disordered eating. Additionally, Oliveira, Trindade and Ferreira [25] demonstrated that, in women, body compassion may lessen the harmful effect of general feelings of shame on body and eating-related attitudes and behaviours.

Despite the extensive research on body image and eating psychopathology, there are no up-to-date studies on the roles that self-compassionate attributes and actions, and body compassion may play on disordered eating attitudes and behaviours. Therefore, the present study aimed to test the mediator effect of self-compassionate actions and body compassion on the relationship between self-compassionate attributes and disordered eating attitudes and behaviours (e.g. overevaluation of weight, pathological dieting, excessive exercise, binge eating) in the general population. Particularly, the tested model hypothesized that the ability to act in accordance with self-compassionate attributes or motivations may be associated with higher levels of body compassion which, in turn, may explain lower levels of disordered eating. These relationships were expected to persist when the effects of BMI and age were taken into account.

Materials and methods

Participants

The sample of this study comprised 299 Portuguese women from the general population, with ages ranging from 18 to 56 years (M = 29.08; SD = 10.18) and presented a mean of years of education of 15.39 (SD = 2.12).

Measures

Body mass index (BMI)

BMI was calculated by dividing self-reported current weight (in kilograms), by the height squared (in metres) (kg/m2).

Compassionate Engagement and Action Scales (CEAS) [1]

CEAS is a self-report measure that includes three scales which evaluate the different flows of compassion: (1) compassion for others; (2) the ability to receive compassion from others; and (3) self-compassion (SC). Each scale is composed of 13 items divided into two subsections: attributes (which evaluate the sensitivity and motivation to deal with suffering with a loving and compassionate attitude; SC_attributes) and actions (which assess the commitment and skills to effectively act to alleviate and prevent suffering; SC_actions). Participants are invited to rate each item according to how frequently it occurs, using a ten-point scale ranging from 1 (“Never”) to 10 (“Always”). Higher scores are indicators of higher levels of compassionate attributes and compassionate actions in the three different directions. In the current study, only the self-compassionate attribute (e.g. “I notice, and am sensitive to my distressed feelings when they arise in me”) and action (e.g. “I take the actions and do the things that will be helpful to me”) subscales were used. In the original study, which presented validation for the American, British and Portuguese populations, CEAS revealed good psychometric characteristics, presenting internal consistencies of 0.74 and 0.89 for self-compassionate attributes and self-compassionate actions, respectively [1].

Body Compassion Scale (BCS) [22, 26]

BCS is a 23-item self-report questionnaire to assess attitudes of compassion towards one’s body, through three subscales (defusion, common humanity, and acceptance). Participants are invited to rate each item (e.g. “When I feel out of shape, I try to remind myself that most people feel this way at some point”, “I am accepting of the way I look without my clothes on”) using a scale ranging from 1 (“Almost Never”) to 5 (“Almost always”). Higher scores on this scale reflect higher body compassion skills. The BCS showed very good psychometric properties in the original [22] and Portuguese versions [26] presenting Cronbach’s alphas of 0.92 and 0.91, respectively.

Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) [27, 28]

The EDE-Q is a 36-item self-report measure that evaluates the presence of disordered eating attitudes and behaviours (e.g. overevaluation of weight, pathological dieting, excessive exercise, binge eating) which occur in the general population along a continuum of severity. It consists of four subscales (restraint, eating concern, shape concern and weight concern). The items are rated for the frequency of occurrence (items 1–15, using a scale ranging from 0 = “None” to 6 = “Every day”) or for severity (items 29–36, ranged from 0 = “None” to 6 = “Extremely”), within a 28-day time frame. Higher scores on this scale reflect a more marked presence of disordered eating attitudes and behaviours. In this study, only the EDE-Q global score (calculated from the mean of the four subscale scores) was used, as we were interested in capturing the severity of disordered eating attitudes and behaviours. EDE-Q has been consistently demonstrated as a valid and reliable measure of disordered eating attitudes and behaviours [27]. Also, the Portuguese version of EDE-Q showed good psychometric properties with a Cronbach’s alpha estimate of 0.94 [28].

Internal consistency of these measures in the current sample is reported in Table 1.

Procedures

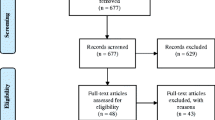

The present study is part of a wider research about the role of emotion regulation on disordered eating. The study procedures complied with all ethical and deontological requirements inherent to scientific research: the Ethic Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Coimbra approved the research, and all participants were fully informed about the nature and objectives of the study, the voluntary nature of their participation and the confidentiality of the data, which were exclusively used for research purposes. Participants were recruited through online advertisements on social networks and by e-mail invitations, using the snowball sampling method. All individuals who accepted to participate in this study provided their written inform consent previously to answering an online version of self-report questionnaires (LimeSurvey). In accordance with the aims of this study, data were cleaned to exclude (1) male participants, (2) participants who were younger than 18 years, and (3) the cases in which more than 15% of the responses from a questionnaire were missing. This cleaning process resulted in the final sample of 299 female participants.

Data analyses

The software IBM SPSS (v.22; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used to perform descriptive and correlation analyses. The descriptive statistics (e.g. means and standard deviations) were used to explore the characteristics of the sample in the study variables.

Pearson correlation analyses were conducted to explore relationships between self-compassionate attributes (SC_attributes) and actions (SC_actions), body compassion (BCS), and the severity of disordered eating attitudes and behaviours (EDE-Q).

Furthermore, path analyses were performed with the software AMOS (Analysis of Momentary Structure, v.22, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) to analyse whether the association between self-compassionate attributes (exogenous variable) and disordered eating attitudes and behaviours (endogenous variable) was mediated by self-compassionate actions and body compassion (endogenous mediator variables), while controlling for BMI and age. Path analyses are a type of structural equation modelling that allows the simultaneous examination of presumed structural relationships (direct and indirect effects) between variables in the proposed theoretical model. The maximum likelihood method was used to estimate model path coefficients and compute fit statistics. Also, to assess the plausibility of the overall mode, a set of goodness-of-fitness indices was calculated and examined, such as the Chi square (χ2), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the root-mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with 95% confidence interval. Bootstrap resampling method was used to test the significance of the mediational paths, using 5000 Bootstrap samples and 95% bias-correlated confidence intervals (CI) around the standardized estimates of total, direct and indirect effects [29]. Effects with p values under 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive and correlation analyses

Descriptive analyses revealed that participants’ body mass index (BMI) mean was 22.87 kg/m2 (SD = 3.52). Specifically, 225 (75.2%) participants had a normal weight (18.5 ≥ BMI ≤ 24.99), 16 (5.4%) were underweight (BMI < 18.5), and 58 (19.4%) were overweight (BMI ≥ 25.0), which reflect the BMI distribution in the female Portuguese population [30]. Regarding disordered eating attitudes and behaviours, the analysis of the EDE-Q’s cut-off value of 4 (which has been considered to be a guide for screening of eating disorders) [27] allowed to verify that only 13 participants presented clinical levels of eating psychopathology.

Results from correlation analyses demonstrated that self-compassionate attributes (SC_attributes) presented positive associations with self-compassionate actions (SC_actions) and body compassion (BCS), with strong and moderate magnitudes, respectively. In turn, self-compassionate attributes revealed a negative and weak association with disordered eating attitudes and behaviours (EDE-Q). Furthermore, results showed that self-compassionate actions presented positive and strong associations with body compassion, and a negative and moderate association with EDE-Q. Body compassion was found to be negatively associated with disordered eating attitudes and behaviours (EDE-Q).

Lastly, BMI presented significant correlations with body compassion, disordered eating attitudes and behaviours, and age. Also, albeit small, age revealed significant associations with self-compassionate actions and body compassion.

Means, standard deviations and Pearson’s correlation coefficients are presented in Table 1.

Path analysis

The purpose of the path analysis was to examine whether self-compassionate actions and body compassion mediated the impact of self-compassionate attributes on disordered eating attitudes and behaviours (EDE-Q). First, this model was tested through a fully saturated model (i.e. with zero degrees of freedom) comprising 27 parameters. The initial analysis of the model revealed that two direct effects were nonsignificant: the direct effects of self-compassionate attributes (bsc_attributes = 0.01; SEb = 0.01; Z = 0.74; p = 0.459) and self-compassionate actions (bsc_actions = − 0.01; SEb = 0.01; Z = − 1.36; p = 0.173) on EDE-Q’s variance. In accordance with these results, these paths were progressively removed, and the model was readjusted.

The final model (Fig. 1) demonstrated that all path coefficients were statically significant (p < 0.050), explained 46%, 36% and 44% of self-compassionate actions, body compassion, and EDE-Q’s variances, respectively. Additionally, this model showed an excellent model fit, revealing a nonsignificant Chi square [χ2(4) = 3.59; p = 0.464] and excellent goodness-of-fit indices (CMIN/df = 0.90; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.00, [IC = 0.00–0.08; p = 0.757]) [29].

Specifically, self-compassionate attributes presented direct effects on self-compassionate actions (β = 0.66; bSC_attributes = 0.72; SEb = 0.05; Z = 15.46; p < 0.001) and on body compassion (β = 0.18; bSC_attributes = 0.40; SEb = 0.14; Z = 2.81; p < 0.010). Furthermore, self-compassionate actions showed a direct effect of 0.38 (bSC_actions = 0.82; SEb = 0.13; Z = 6.09; p < 0.001) on body compassion. Finally, body compassion presented, also, a direct effect of − 0.58 on EDE-Q (bbody compassion = − 0.04; SEb = 0.00; Z = − 13.02; p < 0.001).

The analysis of indirect effects showed that self-compassionate attributes presented an indirect effect on body compassion of 0.26 (95% CI 0.16–0.35), which was partially mediated through self-compassionate actions. In turn, self-compassionate attributes revealed an indirect effect of − 0.25 (95% CI − 0.33 to − 0.18) on EDE-Q, which was totally carried by the mechanisms of self-compassionate actions and body compassion. Finally, self-compassionate actions showed an indirect effect of − 0.22 (95% CI − 0.31 to − 0.13) on EDE-Q, through body compassion.

Overall, the model accounted for 44% of EDE-Q’s variance, revealing that the impact of self-compassionate attributes on disordered eating attitudes and behaviours was totally carried by the effects of self-compassionate actions and body compassion, when controlling the effects of BMI and age.

Discussion

Self-compassionate abilities involve the cultivation of feelings of self-directed warmth, safeness and contentment, and a genuine commitment to foster one’s well-being [31]. In the area of eating psychopathology, several studies conducted with clinical and non-clinical female samples have demonstrated the crucial role of self-compassion to attenuate disordered eating behaviours and attitudes (e.g. [14]). However, the differential roles of self-compassionate attributes and actions as well the role of body image-related compassion on disordered eating attitudes and behaviours remain unclear.

Therefore, the present study explored whether the relationship between self-compassion attributes and disordered eating attitudes and behaviours is mediated by self-compassionate actions and body compassion, in a sample of 299 women.

Results of the correlation analyses were in accordance with previous literature by corroborating the positive association between self-compassion and lower levels of disordered eating attitudes and behaviours [14, 20, 21]. Moreover, this study extends the literature by demonstrating the positive link between self-compassionate attributes and actions and body compassion. Specifically, our results showed that the link between self-compassionate actions and body compassion is significantly stronger than the association with self-compassionate attributes. These results seem to be in line with findings reported by Máximo and colleagues [21] which showed that self-compassionate action’s correlation with body appreciation (a construct associated with body compassion) is of higher magnitude than the association of self-compassionate attributes.

A path analysis was thus conducted to test the role of self-compassionate actions and of body compassion in the relationship between self-compassion attributes and disordered eating attitudes and behaviours. Results showed that, although self-compassionate attributes directly impact body compassion, this effect is partially mediated by self-compassionate actions. In turn, body compassion directly explained disordered eating attitudes and behaviours. Moreover, body compassion also seems to totally mediate the impacts of both self-compassionate attributes and actions on disordered eating attitudes and behaviours. These effects were all highly significant even with the control of the effects of age and BMI, and the model explained 44% of the variance of disordered eating attitudes and behaviours, with excellent model fit.

Through the analysis of this mediational model it is possible to hypothesize that the effect of self-compassionate attributes on body compassion is partially carried by the engagement in specific actions which are congruent to one’s self-compassionate attributes. These results seem to show that body compassion not only appears to be explained by more general self-compassionate abilities, but also, besides having inner motives to be self-compassionate (self-compassionate attributes), implies that one takes on specific actions to deal with difficulties and prevent suffering (self-compassionate actions). Additionally, the current findings seem to enhance the contribution of body-specific compassion to the explanation of disordered eating attitudes and behaviours [22, 25] since the link between general self-compassionate abilities and disordered eating depends on body compassion.

However, these results should be interpreted considering some methodological limitations. First, the main limitation of the present study is its cross-sectional design, which does not allow the inference of causal relationships between the variables. Thus, future research should focus on longitudinal designs to determine the directionality of the study relationships over time. Furthermore, the study sample was exclusively composed of women from the general population, and no diagnostic threshold was established. In this sense, our model should be replicated using different samples (e.g. male and clinical samples) to confirm these study findings. Additionally, the use of self-report measures that may be susceptible to biases and future research should comprise other assessment measures (e.g. interviews). Finally, eating psychopathology is a multi-determined process; therefore, it would be important that future studies would incorporate other constructs or emotional processes (e.g. social comparison based on appearance, striving to avoid inferiority and body image shame).

Nonetheless, this study offers important insights for research and clinical practice. In fact, this is the first study that examined the associations between self-compassionate attributes and actions, body compassion and disordered eating attitudes and behaviours. The most interesting contribution of this study is the demonstration that general self-compassionate attributes and actions directly explain body-related compassion, which in turn mediated its effect on disordered eating attitudes and behaviours. These findings suggest that the capacity to act according to self-compassionate attributes contributes to a higher acceptance and kindness towards the unique characteristics of one’s body image, even when perceived by the individual as undesirable, which may reflect in a smaller proneness to adopt disordered eating attitudes and behaviours. This study seems to highlight the importance of considering self-compassionate skills, which can be learned and trained [31], and body-specific compassion in prevention and intervention programs that target body and eating-related difficulties in women.

References

Gilbert P, Catarino F, Duarte C et al (2017) The development of compassionate engagement and action scales for self and others. J Compassionate Health Care. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40639-017-0033-3

Dalai Lama (2001) An open heart: practising compassion in everyday life. Hodder & Stoughton, London

Gilbert P (2005) Compassion and cruelty: a biopsychosocial approach. In: Gilbert P (ed) Compassion: conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy. Routledge, London, pp 9–74

Gilbert P (2010) Compassion Focused Therapy: Distinctive features. Routledge, London

Gilbert P (2015) The evolution and social dynamics of compassion. Soc Personal Compass 9:239–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12176

Neff KD (2003) Development and validation of a scale to measure self- compassion. Self Identity 2:223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860390209035

Neff KD (2003) Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity 2:85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

MacBeth A, Gumley A (2012) Exploring compassion: a meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev 32:545–552

Neff K, Hsieh Y, Dejitterat K (2005) Self-compassion, achievement goals, and coping with academic failure. Self Identity 4:263–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576500444000317

Neff K, McGehee P (2010) Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self Identity 9:225–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860902979307

Neff K, Kirkpatrick K, Rude S (2007) Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. J Res Pers 41:139–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004

Gilbert P, Procter S (2006) Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clin Psychol Psychother 13:353–379. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.507

Braun TD, Park CL, e Gorin A (2016) Self-compassion, body image, and disordered eating: a review of the literature. Body Image 17:117–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.03.003

Ferreira C, Pinto-Gouveia J, Duarte C (2013) Self-compassion in the face of shame and body image dissatisfaction: implications for eating disorders. Eat Behav 14:207–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.005

Kelly AC, Stephen E (2016) A daily diary study of self-compassion, body image, and eating behavior in female college students. Body Image 17:152–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.03.006

Pinto-Gouveia J, Ferreira C, Duarte C (2014) Thinness in the pursuit for social safeness: an integrative model of social rank mentality to explain eating psychopathology. Clin Psychol Psychother 21:154–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1820

Wasylkiw L, MacKinnon AL, MacLellan AM (2012) Exploring the link between self-compassion and body image in university women. Body Image 9:236–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.01.007

Ferreira C, Matos M, Duarte C et al (2014) Shame memories and eating psychopathology: the buffering effect of self-compassion. Eur Eat Disord Rev 22:487–494. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2322

Kelly AC, Vimalakanthan K, Miller K (2014) Self-compassion moderates the relationship between body mass index and both eating disorder pathology and body image flexibility. Body Image 11:446–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.07.005

Marta-Simões J, Ferreira C, Mendes AL (2016) Exploring the effect of external shame on body appreciation among Portuguese young adults: the role of self-compassion. Eat Behav 23:174–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.10.006

Máximo A, Ferreira C, Marta-Simões. J (2017) Self-compassionate actions and disordered eating behavior in women: the mediator effect of body appreciation. Port J Behav Soc Res 3:32–41. https://doi.org/10.7342/ismt.rpics.2017.3.2.58

Altman J, Linfield K, Salmon P et al (2017) The body compassion scale: development and initial validation. J Health Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317718924

Cash TF (2000) The multidimensional body-self relations questionnaire users manual. 3rd revision. http://www.body-images.com/

Cash T (2004) Body image: past, present, and future. Body Image 1:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1740-1445(03)00011-1

Oliveira S, Trindade I, Ferreira C (2018) The buffer effect of body compassion on the association between shame and body and eating difficulties. Appetite 125:118–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.01.031

Ferreira C, Marta-Simões J, Oliveira S (2017) The body compassion scale: a confirmatory factor analysis with a sample of Portuguese adult (manuscript submitted for publication)

Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ (1994) Assessment of eating disorders: interview of self report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord 16:363e370. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(199412)

Machado PP, Martins C, Vaz AR et al (2014) Eating disorder examination questionnaire: psychometric properties and norms for the Portuguese population. Eur Eat Disord Rev 22:448e453. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2318

Kline RB (2005) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 2nd edn. Guilford Press, New York

Poínhos R, Franchini B, Afonso C et al (2009) Alimentação e estilos de vida da população Portuguesa: Metodologia e resultados preliminares [Alimentation and life styles of the Portuguese population: methodology and preliminary results]. Alimentação Humana 15:43 60

Germer C, Neff K (2013) Self-compassion in clinical practice. J Clin Psychol 69:856–867. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22021

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The present study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Coimbra (Portugal), and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Carvalho Barreto, M., Ferreira, C., Marta-Simões, J. et al. Exploring the paths between self-compassionate attributes and actions, body compassion and disordered eating. Eat Weight Disord 25, 291–297 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0581-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0581-3