Abstract

Purpose

The study aimed to assess the prevalence of underweight and overweight or obesity and their sociodemographic, lifestyle, and health factors in a national adult population in Lao People’s Democratic Republic (PDR) (Laos).

Methods

A national cross-sectional study based on a stratified cluster random sampling was conducted in 2013. The total sample included 2531 individuals 18–64 years, (females = 59.3%; mean age 38.7 years, SD = 12.8) from Laos. Questionnaire interview, blood pressure and anthropometric measurements, and biochemistry tests were conducted. Multinomial logistic regression was utilized to determine the association between sociodemographic, lifestyle and health status factors, and underweight and overweight or obesity relative to normal weight.

Results

Using Asian criteria for body mass index (BMI) classification, 9.7% of the population was underweight (BMI < 18.5, kg/m2), 47.5% had normal weight (BMI 18.5–22.9 kg/m2), 17.5% overweight (23.0–24.9 kg/m2), 19.6% class I obesity (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2), and 5.6% class II obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2) (or 42.8% overweight, class I or class II obesity). In adjusted multinomial logistic regression, female sex (adjusted relative risk ratio-ARRR 0.67, confidence interval-CI 0.45, 0.99), current tobacco use (ARRR 1.57, CI 1.02, 2.41), and having no hypertension (ARRR 0.50, CI 0.26, 0.97) were associated with underweight, and middle and older age (ARRR 1.79, CI 1.41, 2.25), being Lao-Tai (ARRR 1.37, CI 1.06, 1.76), urban residence (ARRR 1.62, CI 1.20, 2.17), having meals outside home (ARRR 1.36, CI 1.04, 1.77), no current tobacco use (ARRR 0.57, CI 0.34, 0.59), low physical activity (ARRR 1.39, CI 1.01, 1.92), having hypertension (ARRR 2.52, CI 1.94, 3.26), and dyslipidaemia (ARRR 1.56, CI 1.21, 2.00) were associated with overweight or obesity.

Conclusion

A dual burden of both adult underweight and overweight or obesity was found in Laos. Sociodemographic, lifestyle, and health status risk factors were identified for underweight and overweight or obesity, which can help in guiding public health programmes to address both these conditions.

Level of evidence

Level V, descriptive cross-sectional survey.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally, over 40 years, the prevalence of underweight (18.5 < kg/m2) reduced from 13.8 to 8.8% in adult men and from 14.6 to 9.7% in adult women, and the prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) increased from 3.2 to 10.8% in adult men and from 6.4 to 14.9% in adult women [1]. The 1994 Lao National Assessment Survey found that 15% of women and 12% of men were underweight (18.5 < kg/m2), and 9.3% of men and women were overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) [2]. In the 2003 Laos World Health Survey, based on self-reported height and weight, the prevalence of underweight was 9.3% (18.5 < kg/m2) and overweight or obesity was 9.8% (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) [3]. The 2008 Lao STEP survey conducted in 9 (5 rural and 4 urban) health districts of Vientiane Capital City found, among 25–64 years olds, a prevalence of 5.1% underweight and 27.4% overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) and 5.8% obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) [4]. There is little recent population-based epidemiological data on the national prevalence and correlates of underweight and overweight/obesity among adults in Laos.

High rates of underweight and overweight or obesity have been described among adults in Southeast Asian countries. Among women (18–49 years) in Myanmar, underweight was 14.1% and overweight/obesity 41.1% (for BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2) [5]; in Indonesia (18 years+), underweight was 12.5% and overweight or obesity (≥ 23 kg/m2) 47.6% [6]; in Bangladesh (35 years+), underweight was 30.4% and overweight or obesity (≥ 23 kg/m2) 23.5% [7]; in Malaysia (18 years+), 51.2% had overweight or obesity (≥ 25 kg/m2) [8]; in Thailand, 40.9% had overweight or obesity (≥ 23 kg/m2) [9]; in Vietnam in 2005, 20.9% were underweight and 16.3% had overweight or obesity (≥ 23 kg/m2) [10].

Undernutrition in adulthood can have negative health effects, including morbidity and mortality [11]. Obesity has been linked to various NCDs, such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis, and specific types of cancer causing increased morbidity and mortality [12]. Factors associated with adult underweight may include sociodemographic variables, such as being female [10, 13, 14], younger and older adults [6, 7, 14], having lower education [6, 7, 13,14,15], poorer economic background [7, 14, 15], not working [7], and living in rural areas [6, 10]. Moreover, not having chronic conditions [6], smoking [5], insufficient food intake, diets with insufficient nutrient density and food insecurity [16], and fear or phobia of being obese [17] may be correlated with underweight.

Sociodemographic risk factors for having overweight or obesity include being female [7, 10], middle aged [7, 14], higher educational levels [6, 7], higher income or economic status [6, 7, 14, 15], urban residence [6, 7, 10, 18], and race or ethnicity [19]. Dietary risk behaviours include the consumption of energy-dense foods high in sugars, fat, and salt [20, 21], and inadequate fruit and vegetables consumption [22]. Physical activity [11, 23, 24] and smoking [20, 21] have been found to decrease the odds of having obesity. Obesity is associated with various chronic conditions such as diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, and hypertension [25, 26]. Laos has a high prevalence of undernutrition in children under the age of 5 years (underweight 25.5%, stunting 35.6%, and wasting 9.6% in 2015) [27], which may affect adult weight status and NCDs.

There is a dearth of information on the national distribution of underweight and overweight or obesity and its correlates in Laos. To better design health interventions, it is of importance to understand factors related to the burden of both underweight and obesity in Laos. The study aimed to assess the prevalence of underweight and overweight or obesity and their sociodemographic, lifestyle, and health factors in a nationally representative adult population in Laos.

Methods

Study design and participants

A multi-stage cluster sampling method was used to select adults aged 18–64 years for the Lao STEPS Survey in 2013. First, all villages were classified as urban or rural based on list of villages available from Lao Statistical Bureau, and 175 sampled villages were selected as the Primary Sampling Unit (PSUs) using the Probability Proportional to Size (PPS) sampling method. Second, in each village, 15 households were selected as the Secondary Sampling Units (SSUs) using systematic random sampling by the Survey team in fieldwork. Only one eligible participant aged between 18 and 64 years in the sampled households was recruited for the survey using the Kish sampling method and using the automated programme for Kish selection in the handheld Personal Digital Assistant (PDA). A total of 2560 Lao residents were randomly selected for participating in this survey, data from 24 respondents were excluded due to missing data on age, and 2531 had complete anthropometric measurements. The response rate for STEP 1 and 2 was about the same 99.2%, and STEP 3 was 98%.

The protocol of the STEPS survey was reviewed and approved by the “Ethics Committee of the Lao People’s Republic (PDR)”, which gave clearance in accordance with regulations in force (Deliberation No. 019/NECHR of 03 January 2013). For our research, we got an authorization from the General Directorate of Lao Tropical and Public Health Institute. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants (literate and illiterate) prior to the study.

Measures

Following WHO STEPS methodology [28], three steps were taken: “step 1, questionnaire interview; step 2, anthropometric and BP measurements; step 3, biochemistry tests. For step 1, handheld devices loaded with eSTEPS software and WHO STEPS questionnaire were used by trained data collectors at respondents’ residences. Questions included tobacco use, alcohol consumption, dietary habits, and the amount of physical activity (PA), raised total cholesterol (TC), cardiovascular diseases, and sociodemographic profiles. Participants were asked about their history of raised blood pressure or blood glucose and treatment. Show cards on different types of tobacco products, alcohol, physical activities, and servings of fruits and vegetables were used to facilitate understanding of the questions by the respondents” [28].

Current tobacco use was measured with two questions, “Do you currently smoke any tobacco products such as cigarettes, cigars or pipes?” and “Do you currently use any smokeless tobacco products such as snuff, chewing tobacco or betel?”(Yes, No) [28]. Current tobacco use was classified as currently smoking and/or using currently smokeless tobacco. Past month binge drinking was assessed by asking participants how many times that they had “for men five or more and for women four or more standard alcoholic drinks in a single drinking occasion during the past 30 days” [28]. Past month binge drinking was defined as one or more binge drinking sessions in the past month.

Daily fruit and vegetable consumption were calculated from four questions, (1) “In a typical week, on how any days do you eat fruit? (2) vegetables?, (3) “How many servings of fruit do you eat on one of those days?” (4) vegetables? (Cronbach’s alpha 0.76), and classified into 1 = less than five total servings (400 g) of fruit and vegetables per day and 0 = five or more servings a day [28].

Having meals per week that were not prepared at home was classified as 0 = zero days and 1 = one or more days per week. Physical activity level was measured based on the duration of moderate and vigorous physical activities (at work, transport, and recreation) in a typical day and week. Physical activity levels were calculated into low, moderate, or high, as per WHO Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) [29]. The GPAQ has been reported to be a reliable questionnaire for physical activity measurement [30]. High physical activity was defined as: “(a) vigorous-intensity activity on at least 3 days and accumulating at least 1500 MET-minutes/week OR (b) 7 or more days of any combination of walking, and moderate- or vigorous-intensity activities accumulating at least 3000 MET-minutes/week. Moderate: a person not meeting the criteria for the ‘High’ category, but meeting any of the following criteria is classified in this category: (a) 3 or more days of vigorous-intensity activity of at least 20 min per day OR (b) 5 or more days of moderate-intensity activity and/or walking of at least 30 min per day OR (c) 5 or more days of any combination of walking, and moderate- or vigorous-intensity activities accumulating at least 600 MET-minutes/week. Low: a person not meeting any of the above-mentioned criteria falls in this category”[28]. Sedentary behaviour was measured with one question, “How much time do you usually spend sitting or reclining on a typical day?” (in hours and minutes) [28]. High sitting time was defined as ≥ 7.5 h/day.

Steps 2 and 3 were conducted at the village; the field survey team coordinated with the village authority for selecting the appropriate place for steps 2 and 3. It involved “taking anthropometric measurements, fasting blood samples, total cholesterol, and High-Density Lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) by trained health staff and research assistants using WHO STEPS standard methodology. Step 2 involved taking height, weight, waist circumference, and BP measurements. The Boso Medicus Uno automatic BP monitor was used to take readings of the participants’ BP. Three BP readings were taken with 3 min interval. Three sizes of cuff were provided to ensure that the best possible readings were taken” [28]. From the three measurements of each systolic and diastolic blood pressure readings, average blood pressure was calculated arithmetically. Raised BP is defined as “systolic BP ≥ 140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mm Hg or where the participant is currently on antihypertensive medication” [31].

Participants’ weights were measured with pre-calibrated electronic weighing scale SECA 872, they had a range difference of 0.05–0.1 kg between the calibrated weights and displayed values. Participants’ height were measured using Wall Mounted Stadiometer. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated according to Asian criteria: “underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5 to < 23.0 kg/m2), overweight (23.0 to < 25.0 kg/m2), obesity (≥ 25 kg/m2), class I obesity (25–29.9 kg/m2), and class II obesity (≥ 30 kg/m2)” [32].

Step 3 involved taking biochemical measurements; fasting blood samples, total cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) using Cardiocheck PA blood meter and using a capillary drop of blood from their fingers. Raised cholesterol was defined as having raised fasting TC ≥ 5.0 mmol/L or currently on medication for raised cholesterol. Diabetes was defined as “fasting plasma glucose levels > = 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL); or using insulin or oral hypoglycaemic drugs; or having a history of diagnosis of diabetes, and pre-diabetes as fasting plasma glucose levels 6.1 to < 7.0 mmol/L)” [33].

Data analysis

Post-stratification weighting accounted for population distribution by districts, gender, and age groups from the national population census projection for 2012 based on the Lao PDR National Census conducted in 2005. Individual weight was performed with the inverse of the probability of selection for each respondent, which was considered as the weight for the individual household.

Descriptive statistics on frequency, weighted prevalence, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) was performed for sociodemographic, behavioural, health, and body weight status variables. Multinomial logistic regression was conducted to assess associations between sociodemographic factors, health variables, and underweight and overweight/obesity (with normal body weight status as reference category). Multi-collinearity was checked; none exceeded a value of 2. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Missing values (< 5%) were excluded from the analysis. All analyses were adjusted for the multi-stage sample design and conducted with STATA software version 13.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Sample characteristics and prevalence of body mass index status

The total sample included 2,531 individuals 18–64 years, (females = 59.3%; mean age 38.9 years, SD = 12.3) from Lao PDR. Overall, 9.7% of the population was underweight (BMI < 18.5, kg/m2), 47.5% had normal weight (BMI 18.5–22.9 kg/m2), 17.5% overweight (23.0–24.9 kg/m2), 19.6% class I obesity (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2), and 5.6% class II obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2) (or 42.8% overweight, class I or class II obesity). Tables 1, 2 summarise the sociodemographic and health characteristics of the sample and by BMI status. In bivariate analyses, BMI status was higher in the older aged, women, urban residence, higher education, being employed, being Lao-Tai, having meals outside the home, those who engaged in binge drinking, in low physical activity, had hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and dyslipidemia. The body weight status was lower in the current tobacco users and the body weight status did not differ by fruit and vegetable consumption and sedentary (sitting) behaviour (see Tables 1, 2).

Table 3 describes the prevalence of underweight and overweight/obesity by age group, sex, areas of residence, and major ethnic groups. The highest prevalence of underweight was in the 55–64 years’ age group (13.1%) and the 18–24 years’ age group (12.1%), while the highest prevalence of overweight or obesity was in the 45–54 years’ age group (52.5%). The prevalence of underweight was overall and in both sexes higher rural than urban areas, while the prevalence of overweight or obesity was overall and in both sexes higher in urban than rural areas. Furthermore, the prevalence of underweight was overall and in both sexes higher in other ethno-linguistic groups such as Mon-Khmer than in the Lao-Tai, while the prevalence of overweight or obesity was overall and in both sexes higher in the Lao-Tai and those in urban areas than in other ethno-linguistic groups and those in rural areas (see Table 3).

Associations with the prevalence of underweight and overweight/obesity

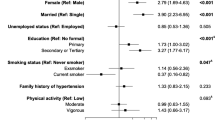

Factors independently associated with underweight were female sex (Adjusted Relative Risk Ratio—ARRR 0.67; confidence Interval—CI 0.45, 0.99), current tobacco use (ARRR 1.57, CI 1.02, 2.41) and having no hypertension (ARRR 0.50, CI 0.26, 0.97). Factors independently associated with overweight or obesity were middle and older age (ARRR 1.79, CI 1.41, 2.25), being Lao-Tai by linguistic group (ARRR 1.37, CI 1.06, 1.76), urban residence (ARRR 1.62, CI 1.20, 2.17), having meals outside home (ARRR 1.36, CI 1.04, 1.77), no current tobacco use (ARRR 1.57, CI 0.34, 0.59), low physical activity (ARRR 1.39, CI 1.01, 1.92), having hypertension (ARRR 2.52, CI 1.94, 3.26), and dyslipidaemia (ARRR 1.56, CI 1.21, 2.00) (see Table 4).

Discussion

In this first nationally representative population-based survey among adults (18–64 years) on body weight status in Lao PDR, the age-adjusted prevalence of underweight (BMI < 18.5, kg/m2) was 9.7% and overweight, class I or class II obesity (≥ 23.0 kg/m2) was 42.8%; 19.6% class I obesity (BMI ≥ 25.0–29.9 kg/m2), and 5.6% class II obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2). This result demonstrates the co-existence of a dual burden of underweight (9.7%) and overweight/obesity (≥ 23 kg/m2) (42.8%) and (≥ 25 kg/m2) (25.3%) in Laos. Similar figures were found in the previous 2008 Laos STEPS survey that concentrated on Vientiane Capital City, 5.1% underweight, and 33.2% overweight/obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) [4], compared with 6.6% underweight and 36.6% overweight/obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) in urban areas in this study. The prevalence of underweight in this study in Laos (9.7%) compares with the global prevalence (8.8% in men and 9.7% in women) [1], but was lower than in previous studies in the Southeast Asian region, e.g., among women (18–49 years) in Myanmar (14.1%) [5], in Indonesia (18 years and older) 12.5% [6], in Bangladesh (35 years and older) 30.4% [7], and in Vietnam 20.9% [10]. The prevalence of overweight or obesity (≥ 23 kg/m2) (42.8%) in this study in Laos was similar to women (18–49 years) in Myanmar (≥ 23 kg/m2, 41.1%) [5], both sexes 18 years and older in Indonesia (≥ 23 kg/m2, 47.6%) [6], and both sexes in Thailand (≥ 23 kg/m2, 40.9%) [9], higher than in Bangladesh (≥ 23 kg/m2, 23.5%) [7] and in Vietnam (≥ 23 kg/m2, 16.3%) [10], lower than in Malaysia (≥ 25 kg/m2, 51.2%) [8], and with 5.6% obesity (≥ 30 kg/m2) lower than the global prevalence of obesity (≥ 30 kg/m2) (10.8% in men and 14.9% in adult women) [1]. Moreover, the investigation demonstrated a decline in the prevalence of underweight from 13.5% in 1994 [2] to 9.7% in 2013, and a stark increase of overweight/obesity (≥ 25 kg/m2) from 9.3% in 1994 [2] to 25.3% (≥ 25 kg/m2) in 2013 in Laos. This decline in the prevalence of underweight and increase in overweight or obesity over the past 20 years echoes global and regional trends [1], such as in Vietnam [10] and Thailand [34].

The study found that the prevalence of underweight was the highest among 18–24 years old (12.1% overall, 10.1% in males and 13.6% in females) and 55–64 years old (13.1%). The previous studies also confirm the higher prevalence of underweight among young adults [14] and older adults [7, 14]. In this study, the prevalence of underweight was significantly higher among women than men, which is consistent with the previous studies [10, 13, 14]. Food insecurity [16] and fear of being obese [17] may be some of the reasons of the high prevalence of underweight during the early adulthood. An increase of an underweight body ideal and in eating disordered attitudes has been reported in Southeast Asia, including Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam [35]. In bivariate analysis, overweight or obesity was higher in women than in men, which is in line with the previous studies [7, 10].

In agreement with the previous studies [7, 10, 13,14,15], this study found, in bivariate analysis, an association between living in rural areas and ethnic minority groups with underweight. Consistent with the previous studies [36, 37], this study found that current tobacco use increased and having hypertension decreased the odds of having underweight.

In terms of overweight or obesity, consistent with the previous studies [7, 10, 11, 15, 19], this study found that being female, being middle and older aged, belonging to the main ethno-linguistic group Lao-Tai and urban residence were associated with having overweight or obesity. The study found a higher prevalence of underweight and lower prevalence of overweight/obesity in other ethno-linguistic groups than in the Lao-Tai. The latter finding was also found in a previous study comparing a group of ethnic minorities and a group of Lao-Tai Laotians in Laos [38]. The authors of this study claim that higher APOE ε4 allele frequencies among minorities (31.3%) than among Lao-Tai (12.6%) may contribute to increases in resting heart rate and less development of hypertension and obesity [38]. In Iran, also ethnic differences in the prevalence of overweight or obesity was observed [19]. Among the different ethno-linguistic groups in Laos, the Lao-Tai have the highest educational levels and lowest poverty rates [39], meaning that the greatest epidemiological transition in terms of increased in overweight or obesity and decrease in underweight may have taken place among the Lao-Tai.

Furthermore, specific dietary behaviour (having meals outside home) and low physical activity were, as previously found [22,23,24], associated with having overweight or obesity. It is likely that eating meals outside the home may increase unhealthy eating such as fast foods. Despite 87% of the Lao population meeting physical activity recommendations and 96.2% not having a high sitting time or sedentary behaviour, a larger contribution to overweight/obesity in the Lao adult population may be related to changes in food consumption and dietary patterns that is probably richer in fats and sugars [9, 40], and very low, only 5.3% of the study population, met fruit and vegetable consumption recommendations. Consistent with the previous investigations [5, 8, 20, 21, 36], this study showed that current tobacco users were less likely to be overweight or obese compared to having normal weight. “Mechanisms through which cigarette smoking reduces body weight are by increasing energy expenditure and inhibiting the expected compensatory increase in caloric intake. Nicotine increases energy expenditure both by direct effects on peripheral tissues, largely mediated by catecholamines, and by effects on central nervous system neuroendocrine circuits. Nicotine’s effects on the brain also lead to suppression of appetite, and smoking per se can serve as a behavioural alternative to eating” [41, p. 161].

The study findings further suggest, as previously found [25, 26], that cardiometabolic comorbidities, including hypertension, dyslipidaemia and in bivariate analysis diabetes, were associated with having overweight or obesity. The Lao Ministry of Health approved “NCD policy and multisectorial action plan for prevention and control of NCDs 2014–2020” includes the implementation of the WHO package for essential non-communicable disease (WHO-PEN) in health facilities [42], which could help in preventing and controlling overweight and obesity.

Study limitations

Apart from blood chemistry, and anthropometric and blood pressure measurements, a study limitation was that all the other information assessed in this analysis was based on self-reporting. It is possible that certain behaviours were over or under reported. Furthermore, it was a cross-sectional study and causal relationships between risk factors and the development of underweight or overweight/obesity cannot be established. Another limitation was that the study population did not include persons 65 years and older, which hindered us from describing the body weight status in the older age group.

Conclusion

The paper found in a national cross-sectional study a high prevalence of both underweight and overweight or obesity among adults (18–64 years) in 2013 in Laos, with underweight declining and overweight or obesity increasing over the past 20 years, as assessed in the previous other studies. Sociodemographic, lifestyle, and health status factors were identified for under- and overweight status, which can guide much needed public health interventions to address both these conditions.

References

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) (2016) Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19.2 million participants. Lancet 387(10026):1377–1396. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30054-X

World Health Organization (WHO) Lao People’s Democratic Republic (1994) Available at http://www.wpro.who.int/nutrition/documents/docs/lao.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2018

Moore S, Hall JN, Harper S, Lynch JW (2010) Global and national socioeconomic disparities in obesity, overweight, and underweight status. J Obes. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/514674

Vang C, Melanie C, Phoxay C, Thongsana S, Sombandith X, Sisamouth B, Douangchack P, Phongsavath K, Boundachoundara I (2010) Report on STEPS survey on non communicable diseases rick factors in Vientiane Capital city, Lao PDR. Available at http://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/steps/2008_STEPS_Report_Laos.pdf. Accessed 12 June 2018

Hong SA, Peltzer K, Lwin KT, Aung S (2018) The prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity and their related socio-demographic and lifestyle factors among adult women in Myanmar, 2015-16. PLoS One 13(3):e0194454. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194454. eCollection 2018

Pengpid S, Peltzer K (2017) The prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity and their related lifestyle factors in Indonesia, 2014–15. AIMS Public Health 4(6):633–649. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2017.6.633

Biswas T, Garnett SP, Pervin S, Rawal LB (2017) The prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity in Bangladeshi adults: data from a national survey. PLoS One 12(5):e0177395. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177395. (eCollection 2017)

Chan YY, Lim KK, Lim KH, Teh CH, Kee CC, Cheong SM, Khoo YY, Baharudin A, Ling MY, Omar MA, Ahmad NA (2017) Physical activity and overweight/obesity among Malaysian adults: findings from the 2015 National Health and morbidity survey (NHMS). BMC Public Health 17(1):733. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4772-z

Jitnarin N, Kosulwat V, Rojroongwasinkul N, Boonpraderm A, Haddock CK, Poston WS (2011) Prevalence of overweight and obesity in Thai population: results of the National Thai Food Consumption Survey. Eat Weight Disord 16(4):e242–e249

Ha do TP, Feskens EJ, Deurenberg P, Mai le B, Khan NC, Kok FJ (2011) Nationwide shifts in the double burden of overweight and underweight in Vietnamese adults in 2000 and 2005: two national nutrition surveys. BMC Public Health 11:62. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-62

Nubé M, Van Den Boom GJ (2003) Gender and adult undernutrition in developing countries. Ann Hum Biol 30(5):520–537

Pi-Sunyer X (2009) The medical risks of obesity. Postgrad Med 121(6):21–33. https://doi.org/10.3810/pgm.2009.11.2074

Letamo G, Navaneetham K (2014) Prevalence and determinants of adult under-nutrition in Botswana. PLoS One 9:e102675. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102675. eCollection 2014

Hanandita W, Tampubolon G (2015) The double burden of malnutrition in Indonesia: social determinants and geographical variations. SMM Population Health 1:16–25 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2015.10.002. eCollection 2015 Dec

Siddiqui MZ, Donato R (2017) Undernutrition among adults in India: the significance of individual-level and contextual factors impacting on the likelihood of underweight across sub-populations. Public Health Nutr 20(1):130–141. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980016001968

Jaacks LM, Slining MM, Popkin BM (2015) Recent trends in the prevalence of under- and overweight among adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries. Pediatr Obes 10(6):428–435. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12000

Delbiso TD, Rodriguez-Llanes JM, Altare C, Masquelier B, Guha-Sapir D (2016) Health at the borders: Bayesian multilevel analysis of women’s malnutrition determinants in Ethiopia. Glob Health Action 9:30204. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v9.30204. (eCollection 2016)

Angkurawaranon C, Jiraporncharoen W, Chenthanakij B, Doyle P, Nitsch D (2014) Urban environments and obesity in southeast Asia: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. PLoS One 9(11):e113547. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0113547. eCollection 2014

Bakhshi E, Koohpayehzadeh J, Seifi B, Rafei A, Biglarian A, Asgari F, Etemad K, Bidhendi Y (2015) Obesity and related factors in Iran: the STEPS survey, 2011. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2015;17(6):e22479. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.17(6)2015.22479. eCollection 2015 Jun

Pengpid S, Peltzer K (2017) Associations between behavioural risk factors and overweight and obesity among adults in population-based samples from 31 countries. Obes Res Clin Pract 11(2):158–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2016.08.001

Moon K, Krems C, Heuer T, Roth A, Hoffmann I (2017) Predictors of BMI vary along the BMI range of German adults—results of the German National Nutrition Survey II. Obes Facts 10(1):38–49. https://doi.org/10.1159/000456665

Carnauba RA, Chaves DF, Baptistella AB, Paschoal V, Naves A, Buehler AM (2017) Association between high consumption of phytochemical-rich foods and anthropometric measures: a systematic review. Int J Food Sci Nutr 68(2):158–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/09637486.2016.1229761

World Health Organization (WHO) (2011) Obesity and overweight fact sheet. Department of Sustainable Development and Healthy Environments. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/entity/noncommunicable_diseases/media/non_communicable_diseases_obesity_fs.pdf. Accessed 10 June 2018

Hruby A, Manson JE, Qi L, Malik VS, Malik VS, Rimm EB, Sun Q, Willett WC, Hu FB (2016) Determinants and consequences of obesity. Am J Public Health 106(9):1656–1662. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303326

Leggio M, Lombardi M, Caldarone E, Tsai SP, Chan HT, Hsu HL, Hsu CC, Eriksen MP (2017) The relationship between obesity and hypertension: an updated comprehensive overview on vicious twins. Hypertens Res 40(12):947–963. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2017.75

DiBonaventura MD, Meincke H, Le Lay A, Fournier J, Bakker E, Ehrenreich A (2017) Obesity in Mexico: prevalence, comorbidities, associations with patient outcomes, and treatment experiences. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 11:1–10. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S129247. eCollection 2018

World Bank (2016) Nutrition in Lao PDR: Causes, determinants, and bottlenecks. Available at http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/706941471934533652/text/107927-WP-P132582-PUBLIC-Nutrition-in-Lao-FA.txt Accessed 26 June 2018

World Health Organization (2017) STEPwise approach to noncommunicable disease risk factor surveillance (STEPS). Available at http://www.who.int/chp/steps/riskfactor/en/. Accessed 18 March 2018

World Health Organization (2012) Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ) analysis guide. World Health Organization, Geneva

Bull FC, Maslin TS, Armstrong T (2009) Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ): nine country reliability and validity study. J Phys Act Health 6:790–804

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR et al (2003) Seventh report of the joint national committee of prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension 42:1206–1252

Wen CP, David Cheng TY, Tsai SP, Chan HT, Hsu HL, Hsu CC, Eriksen MP (2009) Are Asians at greater mortality risks for being overweight than Caucasians? Redefining obesity for Asians. Public Health Nutr 12:497–506. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980008002802

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) (2016) Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet 387(10027):1513–1530. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00618-8

Aekplakorn W, Inthawong R, Kessomboon P, Sangthong R, Chariyalertsak S, Putwatana P, Taneepanichskul S (2014) Prevalence and trends of obesity and association with socioeconomic status in Thai adults: National Health Examination Surveys, 1991–2009. J Obes 2014:410259. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/410259

Pengpid S, Peltzer K (2018) Risk of disordered eating attitudes and its relation to mental health among university students in ASEAN. Eat Weight Disord 23(3):349–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0507-0

Wang Q (2015) Smoking and body weight: evidence from China health and nutrition survey. BMC Public Health 15:1238. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2549-9

Méndez-Chacón E, Santamaría-Ulloa C, Rosero-Bixby L (2008) Factors associated with hypertension prevalence, unawareness and treatment among Costa Rican elderly. BMC Public Health 8:275. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-275

Midorikawa K, Soukaloun D, Akkhavong K et al (2016) APOE genotype in the ethnic majority and minority groups of Laos and the implications for non-communicable diseases. PLoS One 11(5):e0155072. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155072. eCollection 2016

The United Nations in Lao PDR (2015) Country analysis report: Lao PDR analysis to inform the Lao People’s Democratic Republic–United Nations Partnership Framework (2017–2021). Available at http://www.la.undp.org/content/lao_pdr/en/home/library/mdg/country-analysis-report.html (accessed 22 June 2018)

Popkin BM (2009) Global changes in diet and activity patterns as drivers of the nutrition transition. Nestle Nutrition Workshop Series Pediatric Program 63:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1159/000209967

Audrain-McGovern J, Benowitz NL (2011) Cigarette smoking, nicotine, and body weight. Clin Pharmacol Ther 90(1):164–168. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2011.105

Chu V, Keomanisone P (2014) Lao National NCD policy and MSA plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2014–2020. WHO national Office in Lao PDR, Vientiane

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the World Health Organization (WHO) both from Headquarters in Geneva and Regional Office for the financial and technical supporting for this survey. Our sincere gratitude to the Lao STEPS Steering Committee for their intelligent and creative advice and encouragement, and the whole survey team for accomplishing their tasks in preparation and the implementation of this survey. A special thanks also goes to Dr. Keonakhone Houamboune who was the Principal Investigator of the survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants (literate and illiterate) prior to the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pengpid, S., Vonglokham, M., Kounnavong, S. et al. The prevalence of underweight and overweight/obesity and its correlates among adults in Laos: a cross-sectional national population-based survey, 2013. Eat Weight Disord 25, 265–273 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0571-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0571-5