Abstract

Purpose

The current study tested a path model that examined the association between early emotional experiences with peers and male body attitudes and whether general feelings of shame and body-focused shame mediate this relationship, while controlling for the effect of body mass index.

Methods

The sample comprised 241 men from the general community, aged from 18 to 60, who completed an online survey.

Results

Correlation analyses showed that the recall of positive early emotional experiences with peers is inversely linked to shame and negative body attitudes. Path analysis results indicated that early emotional experiences with peers had a direct effect on external shame, and an indirect effect on male negative body attitudes mediated by external shame and body-focused shame. Results confirmed the plausibility of the tested model, which accounted for 40% of the variance of male body attitudes. Findings suggested that men who recall fewer positive early peer emotional experiences tend to perceive that they are negatively viewed by others and present more body image-focused shame experiences. This in turn seems to explain a negative self-appreciation of one’s muscularity, body fat and height.

Conclusions

This study contributes to a better understanding of male body attitudes. Findings suggest that the link between early emotional experiences and male body attitudes may depend on the experience of shame feelings and, particularly, on the extent to which one’s body image becomes a source of shame. These data support the relevance of addressing shame experiences when working with men with body image-related difficulties.

Level of evidence

Level V—cross-sectional descriptive study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Literature has highlighted the importance of early emotional memories on human development and functioning [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Research suggests that the evocation of early memories of warmth and safeness with peers plays a crucial role in the promotion of feelings of self-warmth, self-compassion and self-soothing, which are considered relevant psychological adjustment indicators [7,8,9]. In contrast, early negative emotional memories (e.g., a sense of threat, subordination, and feeling ashamed or unvalued as a child) [10] are associated with a higher vulnerability to psychopathology [11,12,13]. Several authors have indeed demonstrated that the recall of early experiences of threat, abuse, or neglect may guide emotional and cognitive processing and activate defensive responses, such as shame [2, 3, 5].

Shame is an universal emotion rooted in the need for attachment to others. This emotion arises in the social context when individuals believe that others see or evaluate them as inferior, inadequate, defective or unattractive (e.g., [14]). Therefore, shame can be conceptualized as a functional defensive response to social threats [14, 15] activated to attenuate its negative social consequences (e.g., rejection, social criticism and ostracism) [15, 16]. Shame motivates striving or working hard to correct one’s behaviours or features and thus to appear desirable and be accepted by others [8].

Body image has been identified as a salient source of shame because it represents a dimension of the self that can be easily assessed and evaluated by others [e.g., 14, 15, 17]. Body image was defined as the picture that one has in mind of the size, form and shape of body and the feelings one has about these characteristics [18, 19]. Furthermore, body image comprises cognitive (thoughts and beliefs about the body), perceptual, affective (feelings about one’s own body), behavioural and social components, and so the development of body image is influenced by events affecting the body, as well as relationships with others, self-esteem and socialization [18, 19]. In this sense, the display of a valued body image by others plays an important role in the interplay with others and in one’s self-evaluations [20]. Even though literature on body image (e.g., on its phenomenology and emotional impact) has focused mostly on women (e.g., [21, 22]), many researchers have shown that men also experience weight, body shape, and appearance concerns, which can have detrimental effects on physical and psychological well-being indicators [23,24,25]. Indeed research suggests that, for men, physical appearance is a fundamental dimension for self-evaluation and for determining whether one is accepted and valued by others [25, 26].

Historically, women have been the main target of sociocultural pressures (i.e., from peers, family and the media) due to the importance given to physical attractiveness and the presentation of certain beauty standards [20]. Nevertheless, men also face great body-related sociocultural pressures and are directly influenced by them [23, 27, 28]. In Western societies, the representations of the ideal male physical appearance have become more visible and pervasive, being widely focused on a toned, muscular, lean, and physically fit body [21, 29]. In fact, modern societies pressure men to attain a lean-muscular physique (i.e., musculature coupled with low body fat), which promotes body discontent and eating pathology [30,31,32]. It is considered that when men internalize this ideal body image and perceive that their physical appearance fails to fit within this unrealistic body ideal, they may become more critical in regard to their bodies [24] and experience increased negative affect and sense of self-worth (e.g., [33, 34]). As a result, men appear to experience more weight, body shape, and appearance-related concerns, which can have detrimental effects, like body shame, body surveillance and body dissatisfaction, which in turn lead to increased compensatory drive for muscularity [35,36,37] and disordered eating behaviours (e.g., [38]). Thus, for some men, sociocultural pressures may lead to negative self-evaluations based on one’s body image (i.e., body image-focused shame) which might promote negative body attitudes and pathological attempts to control physical appearance as defensive strategies in face of these unwanted experiences [31, 32]. Literature have documented the relationship between shame and body and eating-related difficulties in both men and women from clinical and non-clinical samples [39,40,41,42,43]. In particular, disordered eating attitudes and behaviours (such as drive for thinness or binge eating symptomatology) may be conceptualized as maladaptive coping strategies to control or attenuate body shame and guilt feelings [33, 44, 45].

Although there is a recognized need to further study the mechanisms that may explain body image difficulties in men, few studies have focused on that. Given the pervasive and negative impact of body image shame and negative body attitudes, it is considered that research should focus on the analysis of potential factors and mechanisms involved in these difficulties to inform the development of prevention and intervention programmes on these areas. Also, considering the aforementioned impact of early memories with peers and shame on eating psychopathology and body image concerns (although mainly on women) [44, 46,47,48], the current study aims to innovatively explore the role of these constructs in men’s body image. This paper thus aims to test an integrative model using a male sample, to examine the relationship between early memories with peers and negative attitudes towards the body, and to test whether external shame and body image shame significantly act on this association.

Materials and methods

Participants

The sample included 241 men from the Portuguese general population aged between 18 and 60 years old, with a mean age of 27.24 (SD 9.18) and a mean of 14.03 (SD 2.62) years of education. Participants’ BMI ranged between 16.98 and 43.60, with a mean of 24.75 Kg/m2 (SD 3.95), which corresponds to normal weight values according to the conventional classification [49]. Also, participants’ BMI distribution was similar to the distribution found in the Portuguese male population of the same age [50].

Measures

Demographics

Participants completed a demographic questionnaire (age, gender, nationality, area of residence, education level, and current weight and height).

Body mass index

Participants’ BMI was calculated through the Quetelet Index based on self-reported weight and height (kg/m2).

Early memories of warmth and safeness scale-peers

EMWSS-peers [51] is a 12-item self-report questionnaire derived from the EMWSS [6], and designed to specifically assess the recall of experiences of warmth, safeness, and affection within peer relationships (i.e., with friends and colleagues). Respondents are asked to indicate the frequency of these positive emotional memories (e.g., “I felt safe and secure with my peers/friends”) using a 5-point scale (ranging from 0 = “No, never” to 4 = “Yes, most of the time”). EMWSS-peers revealed good psychometric properties, presenting very good internal reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.97 [51].

The other as shamer scale

OAS-2 [52] is a shorter version of the OAS [53], designed to assess external shame, that is, the perception of being negatively evaluated by others. This scale comprises eight items (e.g., “other people see me as small and insignificant”) scored on a five-point scale (from 0 = “Never” to 4 = “Almost always”), which refers to the frequency of the participants’ perceptions of negative social evaluations. This scale has demonstrated good psychometric characteristics, presenting a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82 in the original study [52].

Body image shame scale

BISS [17] is a 14-item self-report measure, which evaluates the experience of body image-focused shame. The BISS comprises two subscales: external body shame (that is, perceptions that one is negatively evaluated or judged by others because one’s physical appearance) and internal body shame (i.e., negative self-evaluations due to one’s physical appearance). Respondents are asked to rate each item according to which they experience shame about their body image, using a five-point scale (ranging from 0 = “Never” to 4 = “Almost always”). In the current study, the global score of the BISS was used, which presented a high internal consistency in the original study (α = 0.92) [17].

Male body attitudes scale

MBAS [54, 55] is a 24-item self-report scale that assesses male body attitudes. MBAS includes three subscales: muscularity (e.g., “I think I have too little muscle on my body”), body fat (e.g., “I think my body should be leaner”) and height (e.g., “I wish I was taller”). Participants are asked to rate each item using a 6-point scale (ranging from 1 = “Never” to 6 = “Always”). Higher scores indicate greater male body negative appreciation. Cronbach’s alpha of the original version is 0.93 [54], and in the Portuguese version is of 0.92 [55].

Participants completed the Portuguese versions of the described measures, which were previously validated in Portuguese samples with similar characteristics to the present one (e.g., regarding gender and age). Each measure showed an adequate to very good internal reliability in the current study (Table 1).

Procedures

The present study’s procedures respected all ethical and deontological requirements inherent to scientific research and the study was approved by the Ethical Board of the Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences of the University of Coimbra. An invitation to participate in this study was electronically sent through popular social networks and e-mail to potential participants. Attached to the invitation were detailed information regarding the purpose and procedures of the study, data conditionality, the voluntary nature of the participation, and the link to the online platform with the informed consent and test battery. Five hundred and ninety-five individuals accepted to take part in the current research, signed the informed consent and completed the test battery on the online platform. Considering the aims of the present study, the database was cleaned to exclude: (i) female participants; (ii) participants who do not have Portuguese nationality, and (iii) participants younger than 18 and older than 60. This process resulted in a final sample of 241 male participants. There were no missing data because the platform only allows the submission of the questionnaires when all data is complete.

Data analyses

The software IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 (SPSS IBM; Chicago, IL, USA) was used to conduct descriptive and correlation analyses. Pearson correlation coefficients analyses were performed to examine the associations between age, BMI, early positive memories with peers, external shame, body image shame and male body negative attitudes. These coefficients were interpreted in accordance with Cohen et al.’s guidelines (2003): small size effect (r = 0.10–0.29), moderate (r = 0.30–0.49), large (r = 0.50–0.69), very large (r = 0.70–0.89), nearly perfect (r ≥ 0.90), and perfect (r = 1) [56].

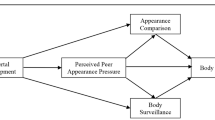

The AMOS software was used to examine the proposed theoretical model (Fig. 1) which tested the hypothesis that early memories of warmth and safeness within peers (exogenous, independent variable) would present a significant effect on male body attitudes (endogenous, dependent variable), through the mediational effects of external shame and body-focused shame (endogenous, mediator variables). BMI’s effects were controlled for due to their known association with body attitudes and body dissatisfaction.

Path model showing the association between early positive emotional memories with peers and male body attitudes, mediated by external shame and body image shame, with standardized estimates and square multiple correlations (R2, N = 241). ***p < 0.001; EMWSS-peers Early Memories of Warmth and Safeness with Peers Scale

A path model estimated using the Maximum Likelihood estimation method was used to calculate the significance of the regression coefficients and the model fit statistics. The adequacy of the model was examined considering the following goodness of fit indices: Chi square (χ2), when nonsignificant indicates a very good model fit; the normed Chi square (CMIN/df), that indicates an acceptable fit when < 5; the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), which indicate a very good fit with values above 0.95; and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation index (RMSEA), which indicates an adequate fit when values < 0.08 [57, 58]. The bootstrap procedure (with 5000 samples) was used to create 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals around the standardized estimates of the significance of total, direct and indirect effects. The effect is statistically significant (p < 0.50) if zero is not included between the lower and the upper bound of the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval [57].

Results

Descriptive and correlation analyses

The descriptive and correlations between the study variables are reported in Table 1. Results from correlation analyses showed that memories of early warmth and safeness with peers (EMWSS-peers) were associated with higher levels of external shame (OAS-2), body image shame (BISS) and male negative body attitudes (MBAS), the same is to say that men who recall more positive early memories with peers tend to present lower levels of external shame, body image shame and negative body attitudes. Higher levels of external shame were linked with higher levels of body image-focused shame, which were associated with more negative male body attitudes. In other words, men who present higher levels of external shame tend to present higher levels of body image shame and negative attitudes towards the body.

Finally, age presented a significant, positive and moderate association with BMI, and a small negative association with EMWSS-P and OAS-2. The same is to say that older men tend to present higher BMI and lower levels of external shame and also less positive memories with peers. BMI revealed significant and positive associations with BISS (with a moderate correlation magnitude) and MBAS (with a weak correlation magnitude), respectively. In other words, men who present higher BMI tend to show higher levels of body image shame and negative male body attitudes.

Path analysis

A path analysis was performed to test whether external shame (OAS-2) and body image shame (BISS) mediate the impact of early memories of warmth and safeness with peers (EMWSS-peers) on men’s attitudes towards their body (MBAS), while controlling for the effect of BMI.

First, the path model was tested through a fully saturated model (i.e., zero degrees of freedom), comprising 20 parameters, which explained 40% of the variance of male body attitudes. Results indicated that three paths were not significant: the direct effect of early memories of warmth and safeness with peers on BISS (bEMWSS-Peers = − 0.005; SEb = 0.065; Z = − 0.0081; p = 0.935); the direct effect of early memories of warmth and safeness with peers on male body attitudes (bEMWSS-Peers = 0.059; SEb = 0.128; Z = 0.459; p = 0.646), and the direct effect of external shame on male body attitudes (bOAS-2= 0.362; SEb = 0.203; Z = 1.784; p = 0.074). These paths were progressively eliminated and the model was readjusted.

The final model presented an excellent model fit [χ2(3) = 3.38, p = 0.34, CMIN/DF = 1.127; TLI = 0.994; CFI = 0.998; RMSEA = 0.023, p = 0.571; 95% CI = 0.00–0.11, Kline, 2005]. This model, in which all path coefficients were statistically significant (p < 0.001), except the direct effect of BMI on external shame (bBMI = − 0.121; SEb = 0.081; Z = − 1.502; p = 0.133) and the direct effect of BMI on male body attitudes (bBMI = 0.511; SEb = 0.272; Z = 1.874; p = 0.061). These paths were nonetheless maintained in the model to control for the effect of BMI.

Early memories of warmth and safeness with peers had a significant direct effect of − 0.43 on OAS-2 (bEMWSS-Peers = − 0.0266; SEb = 0.036; Z = − 7.344; p < 0.001). In turn, external shame had a direct effect of 0.38 on BISS (bOAS-2 = 0.630; SEb = 0.095; Z = 6.627; p < 0.001) and BMI had a direct effect of 0.33 on BISS (bBMI = 0.76; SEb = 0.132; Z = 5.768; p < 0.001). Results also showed that BISS had a direct effect of 0.59 on MBAS (bBISS = 1.317; SEb = 0.117; Z = 11.234; p < 0.001).

The analysis of indirect effects showed that early memories of warmth and safeness with peers presented indirect effects on male body attitudes through external shame and body image shame of − 0.16 (95% CI − 0.099/− 0.056) and − 0.10 (95% CI − 0.142/− 0.056), respectively. External shame and body image shame thus mediated the association between early memories of warmth and safeness with peers and body attitudes Results also demonstrated that external shame had an indirect effect of 0.22 (95% CI 0.140/0.305) on male body attitudes, which was totally mediated through body image shame.

Overall, this model accounted for 40% of the variance of male body attitudes, and revealed that external shame and body image shame mediate the impact of early memories of warmth and safeness with peers on male body attitudes.

Discussion

Literature has highlighted that the inability to recall early warmth and safeness memories can lead to negative emotional states (e.g., [1, 6, 10, 51, 59]). Additionally, the impact of early positive memories on body-related difficulties, among women was recently documented (e.g., [47, 48, 60]). However, it is recognized that men also experience body image concerns which seems to have an important impact on physical and psychological health indicators [22, 24, 54, 55]. Nevertheless, the link between early emotional memories and male body attitudes remained unexplored.

This study intended to clarify the dynamic relationship between early memories, external shame, body image shame, and male body attitudes. Specifically, the main aim of the current study was to test an integrative model that explored the effect of early memories of warmth and safeness on male body attitudes and the mediating roles of current general feelings of shame and body image shame in this association, while controlling the effect of BMI.

In accordance with previous theoretical and empirical contributions (e.g., [46,47,48]), correlational results demonstrated that the recall of early positive memories was negatively linked with emotional defensive responses, such as external shame and body image shame. This seems to suggest that individuals who have higher ability to recall positive, affiliative, or safeness memories with peers from childhood or adolescence, tend to present lower levels of general and body image shame. These individuals thus seem to have a better perception of what others think of them (e.g., a person with value, attractiveness, and success), both in general and specifically concerning body image. Also, findings corroborated prior research demonstrating that external shame, that is perceptions of being negatively seen by others (e.g., as inferior, unattractive, or inadequate), is related to negative body attitudes [e.g., 31, 39, 42], which extends previous studies conducted with women by further showing this relationship in men.

The findings from the conducted path analysis revealed that the model which aimed to understand the relationship between early emotional peer experiences and male body attitudes was plausible, explaining a total of 40% of the variance of the severity of male negative body attitudes. Also, this model demonstrated that 19% of external shame’s variance was explained by the inability to recall positive early emotional memories with peers. Furthermore, results suggested that lack of access to early positive memories had an indirect effect through external shame on body image shame, even when controlling for BMI.This suggests that the difficulty to access memories of warmth, acceptance or safeness is related to an increased activation of the threat system and thus to perceptions that others perceive the self as inferior or inadequate in general (which corroborates previous findings) [2, 10, 51] and also on evaluations based on body image. Although this is in line with research on the role that early negative social experiences, especially those that occurred with peers, plays in body and eating difficulties (e.g., [46,47,48, 60]), the current paper extends literature by suggesting that the recall of these emotional experiences is relevant in men and contributes to understand male body-related difficulties. These are in fact new and particularly interesting findings, especially considering that previous studies have privileged women samples (e.g., [18, 19, 22, 29]).

In fact, some studies support that negative emotional experiences (namely with peers) (e.g., [6, 11, 33]) and body-related shame and guilt are associated with disordered eating and even eating disorders, including binge eating [33, 45], and our findings reinforce this idea showing that lack of positive memories with peers is positively associated with negative body attitudes in men, such as perceptions of low muscle mass and undesirable height or body fat. Moreover, the present study also suggests that the relationship between early peer-related emotional experiences and current male body attitudes is complex and influenced by different mechanisms. Indeed, results indicated that men’s inability to recall early positive emotional experiences with peers (such as experiences of care and warmth) are associated with high levels of negative body attitudes. This relationship was mediated by perceptions of social inferiority (external shame) and body image-focused shame, which seem explain a negative appreciation of male body image (muscularity, body fat and height). Moreira and Canavarro in a sample of children and adolescents with overweight and obesity have reported that body shame assumed different roles by gender in the explanation of quality of life. Indeed, the same authors [61] reported that body shame is more relevant for the well-being and psychosocial adjustment in female samples than in male samples. Although our findings do not explore gender differences, results suggested that, for adult men, body image shame has also a significant impact on the adoption of negative body attitudes, which may lead to detrimental effects on physical and psychological well-being indicators [23, 25, 33, 34]. These novel findings seem to suggest the importance of addressing shame in the comprehension and interventions approaches for body image difficulties in men.

To sum up, difficulty in recalling of feelings of warmth and safeness in early social relationships seems to explain increased levels of shame and a heightened sense of having an unattractive body. This might suggest that the lack of feelings of having had secure and accepting relationships with peers at a young age may lead to feelings of being rejected or seen as inferior or undesirable by others and to perceptions that one’s physical appearance is different from the ideal male body image. Altogether, these mechanisms may lead to the need to control or conceal physical appearance to enhance social acceptance and desirability, which may encourage the adoption of negative attitudes towards one’s perceived body-related imperfections and flaws.

This study should not be considered without taking in account some limitations. First, these findings are based on cross-sectional data and therefore causal conclusions cannot be drawn. Future research should use longitudinal designs to better understand the studied mechanisms and their effect on male body dissatisfaction and negative body attitudes. Also, the current study examined a parsimonious model, and future studies should explore the role of other relevant variables and emotional processes on male body attitudes (e.g., self-esteem, body-esteem, body satisfaction, satisfaction with muscularity). Moreover, results were based on self-reported data collected through an online survey, which may compromised the collection of a representative sample of the Portuguese male adult population and the presentation of definite results. Indeed, online surveys may excluded people who do not have access to the internet or are not familiarized with this virtual world (e.g., [62]), which may have biased the sample regarding education level. Moreover, there is no guarantee of the accuracy of self-reported demographic or characteristics information [63, 64]. Although this is a cost-benefit method, future research should use different assessment methods (e.g., a paper–pencil form or interviews) to explore the plausibility of the current model. Finally, another limitation to this study is that sexual orientation of the participants was not assessed. Given the evidence that gay and bisexual men report more body concerns and dissatisfaction, drive for thinness, drive for muscularity and eating disorder symptomatology than heterosexual men [65, 66], it is important that future research should assess sexual orientation and examine the studied relationships while considering potential differences between heterosexual and non-heterosexual men.

To our present knowledge, this is the first study to focus on the relationship between early emotional experiences and male body attitudes. This study contributes for a better understanding of the possible pathways through which early emotional experiences with peers exert their effect on male body attitudes. Research related to male body image seems to be greatly needed, and the current findings may have important implications for future research as well as for prevention and intervention programmes with men with body image difficulties. Addressing shame feelings by cultivating self-compassion (e.g., compassion-focused approaches) [7] may help attenuate the impact of the lack of early positive memories and improve one’s relationship with their body. Developing self-acceptance and respect with the unique characteristics of one’s body image may be useful to decrease shame levels and develop a positive body image.

Conclusions

This study contributes to a better understanding of male body attitudes, suggesting that men who recall fewer positive early peer emotional experiences tend to perceive that they are negatively viewed by others and to present more body image-focused shame experiences and severe negative body image attitudes. Moreover, current findings highlight that the impact of early emotional experiences on male body attitudes is fully carried by the experience of shame and, particularly, by perceptions that one’s body image may be a source of feelings of inferiority and inadequacy.

References

Cunha M, Martinho MI, Xavier AM, Espirito-Santo H (2013) Early memories of positive emotions and its relationships to attachment styles, self-compassion and psychopathology in adolescence. Eur Psychiatry 28(Supl 21):1. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(13)76444-7

Cunha M, Matos M, Faria D, Zagalo S (2012) Shame memories and psychopathology in adolescence: the mediator effect of shame. IJP&PT 12(2):203–218

Dunlop R, Burns A, Bermingham S (2001) Parent-child relations and adolescent self-image following divorce: a 10 year study. J Youth Adolesc 30:117–134. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010389923248

Gilbert P, Irons C (2005) Focused therapies and compassionate mind training for shame and self-attacking. In: Gilbert P (ed) Compassion: conceptualizations, research and use in psychotherapy. Routledge, London, pp 263–325

Matos M, Pinto-Gouveia J (2010) Shame as a traumatic memory. Clin Psychol Psychother 4:299–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.659

Richter A, Gilbert P, McEwan K (2009) Development of an early memories of warmth and safeness scale and its relationship to psychopathology. Psychol Psychother Theory Res Pract 82:171–184. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608308X395213

Gilbert P, Irons C (2009) Shame, self-criticism, and self-compassion in adolescence. In: Allen N, Sheeber L (eds) Adolescent emotional development and the emergence of depressive disorders. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 195–214

Gilbert P, Procter S (2006) Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clin Psychol Psychother 13(6):353–379. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.507

Mikulincer M, Shaver PR (2007) Attachment in adulthood: structure, dynamics, and change. Guilford, New York

Gilbert P, Cheung M, Grandfield T, Campey F, Irons C (2003) Recall of threat and submissiveness in childhood: Development of a new scale and its relationship with depression, social comparison and shame. Clin Psychol Psychother 10(2):108–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.359

Ferreira C, Matos M, Duarte C, Pinto-Gouveia J (2014) Shame memories and eating psychopathology: The buffering effect of self-compassion. Eur Eat Disord Rev 22(6):487–494. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2322

Serino S, Dakanalis A, Gaudio S, Carrà G, Cipresso P, Clerici M, … Riva G (2015) Out of body, out of space: Impaired reference frame processing in eating disorders. Psychiatry Res 230(2):732–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.10.025

Xavier A, Cunha M, Pinto-Gouveia J (2015) Deliberate self-harm in adolescence: the impact of childhood experiences, negative affect and fears of compassion. Rev Psicopatol Psicol Clín 20(1):41–49. https://doi.org/10.5944/rppc.vol.1.num.1.2015.14407

Gilbert P (2002) Body shame: a biopsychosocial conceptualization and overview, with treatment implications. In: Gilbert P, Miles J (eds) Body shame: conceptualisation, research and treatment. Routledge, London, pp 3–54

Gilbert P (2000) The relationship of shame, social anxiety and depression. The role of the evaluation of social rank. Clin Psychol Psychother 7(3):174–189. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-0879(200007)7:3%3C174::AID-CPP236%3E3.0.CO;2-U

Cacioppo JT, Patrick B (2008) Loneliness: human nature and the need for social connection. Norton, New York

Duarte C, Pinto-Gouveia J, Ferreira C, Batista D (2015) Body image as a source of shame: a new measure for the assessment of the multifaceted nature of body image. Clin Psychol Psychother 22(6):656–666. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1925

Slade PP (1988) Body image in anorexia nervosa. Br J Psychiatry 153(2):20–22

Slade P (1994) What is body image? Behav Res Ther 32:497–502

Strahan EJ, Wilson AE, Cressman KE, Buote VM (2006) Comparing to perfection: how cultural norms for appearance affect social comparisons and self image. Body Image 3:211–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.07.004

Pope HG, Phillips KA, Olivardia R (2000) The adonis complex: how to identify, treat, and prevent body obsession in men and boys. Touchstone, New York

Jones W, Morgan J (2010) Eating disorders in men: a review of the literature. JPMH 9(2):23–31. https://doi.org/10.5042/jpmh.2010.0326

Blond A (2008) Impact of exposure to images of ideal bodies on male body dissatisfaction: a review. Body Image 5(3):244–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.02.003

Burlew LD, Shurts WM (2013) Men and body image: current issues and counseling implications. J Couns Dev 91(4):428–435. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00114.x

Calogero R (2009) Objectification processes and disordered eating in British women and men. J Health Psychol 14(3):394–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105309102192

Dakanalis A et al (2012) Disordered eating behaviours among Italian men: objectifying media and sexual orientation differences. Eat Disord 20(5):356–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2012.715514

Dakanalis A, Carrà G, Calogero R, Fida R, Clerici M, Zaneti M (2015) The developmental effects of media-ideal internalization and self-objectification processes on adolescents’ negative body-feelings, dietary restraint, and binge eating. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24(8):997–1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0649-1

Stanford JN, McCabe MP (2002) Body image ideal among males and females. Sociocultural influences and focus on different body parts. J Health Psychol 7(6):675–684. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105302007006871

Cafri G, Thompson JK (2004) Measuring male body image: a review of the current methodology. Psychol Men Masculin 5(1):18–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/1524-9220.5.1.18

Benowitz-Fredericks CA, Garcia K, Massey M, Vasagar B, Borzekowski DL (2012) Body image, eating disorders, and the relationship to adolescent media use. Pediatr Clin N Am 59:693–704

Calogero RM, Thompson JK (2010) Gender and body image, vol 2. In: Chrisler JC, McCreary DM (eds) Handbook of gender research in psychology, 1st edn. Springer, New York, pp 153–184

Dakanalis A, Riva G (2013) Mass media, body image and eating disturbances: the underlying mechanism through the lens of the objectification theory. In: Sams LB, Keels JA (eds) Body image: gender differences, sociocultural influences and health implications, 1st edn. Nova Science Publishers, New York, pp 217–236

Duarte C, Pinto-Gouveia J (2017) Self-defining memories of body image shame and binge eating in men and women: Body image shame and self-criticism in adulthood as mediating mechanisms. Sex Roles. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0728-5

Grieve FG (2007) A conceptual model of factors contributing to the development of muscle dysmorphia. Eat Disord 15(1):63–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640260601044535

Agliata D, Tantleff-Dunn S (2004) The impact of media exposure on males’ body image. J Soc Clin Psychol 23:7–22

Bartlett CP, Vowels CL, Saucier DA (2008) Meta-analyses of the effects of media images on men’s body image concerns. J Soc Clin Psychol 27(3):279–310

Lorenzen LA, Grieve FG, Thomas A (2004) Exposure to muscular male models decreases men’s body satisfaction. Sex Roles 51:743–748

Murray S, Nagata J, Griffiths S, Calzo J, Brown T, Mitchison D, Mond J (2017) The enigma of male eating disorders: a critical review and synthesis. Clin Psychol Rev 57:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.08.001

Cavalera C, Pagnini F, Zurloni V, Diana B, Realdon O, Castelnuovo G, Enrico M (2016) Shame proneness and eating disorders: a comparison between clinical and non-clinical samples. Eat Weight Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0328-y

Doran J, Lewis CA (2012) Components of shame and eating disturbance among clinical and non-clinical populations. Eur Eat Disord Rev 20:265–270. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1142

Gee A, Troop NA (2003) Shame, depressive symptoms and eating, weight and shape concerns in a non-clinical sample. Eat Weight Disord 8:72–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.605

Gilbert P, Miles J (2014) Body shame: conceptualisation, research and treatment. Routledge, New York

Duffy ME, Henkel KE (2016) Non-specific terminology: moderating shame and guilt in eating disorders. Eat Disord 24(2):161–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2015.1027120

Pinto-Gouveia J, Ferreira C, Duarte C (2014) Thinness in the pursuit for social safeness: an integrative model of social rank mentality to explain eating psychopathology. Clin Psychol Psychother 21(2):154–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1820

Schulte SJ (2016) Predictors of binge eating in male and female youths in the United Arab Emirates. Appetite 105:312–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.06.004

Ferreira C, Marta-Simões J, Trindade I (2016) Defensive responses to early memories with peers: a possible pathway to disordered eating. Span J Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2016.45

Mendes L, Marta-Simões J, Ferreira C (2016) How can the recall of early affiliative memories with peers influence on disordered eating behaviours? Eat Weight Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0267-7

Oliveira S, Ferreira C, Mendes AL (2016) Early memories of warmth and safeness and eating psychopathology: the mediating role of social safeness and body appreciation. Psychologica 59(2):45–60. https://doi.org/10.14195/1647-8606_59_2_3

WHO (1995) Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. In: Reports of a WHO Expert Committee. WHO technical report series, vol 854. World Health Organization, Geneva

Poínhos R et al (2009) Alimentação e estilos de vida da população Portuguesa: metodologia e resultados preliminares (Alimentation and life styles of the Portuguese population: methodology and preliminary results). Aliment Hum 15(3):43–60

Ferreira C, Cunha M, Marta-Simões J, Duarte C, Matos M, Pinto-Gouveia J (2017) Development of a measure for the assessment of peer-related positive emotional memories. Psychol Psychother Theory Res Pract. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12146

Matos M, Pinto-Gouveia J, Gilbert P, Duarte C, Figueiredo C (2015) The Other As Shamer Scale-2: development and validation of a short version of a measure of external shame. Pers Individ Differ 74:6–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.037

Goss K, Gilbert P, Allan S (1994) An exploration of shame measures-I: the ‘other as Shamer’ scale. Pers Individ Differ 17(5):713–717. https://doi.org/10.1016/01918869(94)90149-X

Tylka TL, Bergeron D, Schwartz JP (2005) Development and psychometric evaluation of the Male Body Attitudes Scale (MBAS). Body Image 2(2):161–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.03.001

Ferreira C, Oliveira S, Marta-Simões J, Mendes AL (2017) Male Body Attitudes Scale: Confirmatory factor analysis and its relationship with body image shame and body compassion (manuscript accepted for publication)

Cohen J, Cohen P, West S, Aiken L (2003) Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioural sciences, 3rd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New Jersey

Kline RB (2005) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 2nd edn. The Guilford Press, New York

Tabachnick B, Fidell L (2013) Using multivariate statistics, 6th edn. Pearson, Boston

Ferreira C, Pinto-Gouveia J, Duarte C (2013) Self-compassion in the face of shame and body image dissatisfaction: Implications for eating disorders. Eat Behav 14(2):207–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.005

Ferreira C, Oliveira S, Mendes L (2017) Kindness toward one’s self and body: exploring mediational pathways between early memories and disordered eating. Span J Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.201750

Moreira H, Canavarro MC (2017) Is body shame a significant mediator of the relationship between mindfulness skills and the quality of life of treatment-seeking children and adolescents with overweight and obesity? Body Image 20:47–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.11.004

Faleiros F, Käppler C, Pontes F, Silva S, Goes F, Cucick C (2016) Uso de questionário online e divulgação virtual como estratégia de coleta de dados em estudos científicos. Texto Contexto Enferm 25(4):e3880014

Andrews D, Nonnecke B, Preece J (2003) Electronic survey methodology: a case study in reaching hard-to-involve Internet users. Int J Hum Comput Interact 16(2):185–210

Dillman DA (2000) Mail and internet surveys: the tailored design method. Wiley, New York

Yean C, Benau EM, Dakanalis A, Hormes JM, Perone J, Timko CA (2013) The relationship of sex and sexual orientation to self-esteem, body shape satisfaction, and eating disorder symptomatology. Front Psychol 4:1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00887

Calzo JP, Corliss HL, Blood EA, Field AE, Austin SB (2013) Development of muscularity and weight concerns in heterosexual and sexual minority males. Health Psychol 32(1):42–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028964

Funding

Research by the author Inês A. Trindade is supported by a Ph.D. Grant (SFRH/BD/101906/2014) sponsored by FCT (Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors SO and CF designed the study, prepared the measures and designed the research battery. Author SO recruited the sample. Authors SO and CF conducted the literature research. Authors SO and IAT conducted the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. C F approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oliveira, S., Trindade, I. & Ferreira, C. Explaining male body attitudes: the role of early peer emotional experiences and shame. Eat Weight Disord 23, 807–815 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0569-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0569-z