Abstract

While much research has focused on overeating when exploring constructs of mindfulness, mindful eating, and self-compassion, there is limited research on the specific relationship of these constructs with consumption of energy-dense foods that have a large impact on weight regulation. In a cross-sectional study, university students (n = 546) were recruited to explore the relationship between mindfulness, mindful eating, self-compassion, and fat and/or sugar consumption. Results indicated that all constructs were negatively related to fat and sugar consumption, but self-compassion did not do so in a univariate fashion. When investigating subscales, negative aspects such as isolation and over-identification show a significant positive relationship to fat and sugar consumption. Possible explanations and future directions are discussed further with an emphasis on the need for more empirical work.

Level of Evidence: Level V, cross-sectional descriptive study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The typical diet in Western countries is characterized by energy-dense food, high in saturated fat and/or sugars [1,2,3,4]. This diet plays a major role in the obesity epidemic and has an etiology of associations with a range of chronic diseases including heart diseases and diabetes [5]. A report by the World Health Organization [6] recommended reducing the consumption of energy-dense foods as a primary goal for the prevention of diet-related chronic diseases. While constructs such as mindfulness, mindful eating, and self-compassion have been explored in association with eating behaviors, eating disorders, and obesity, the direct association between these constructs and fat and sugar consumption has not been explored.

Dietary guidelines recommend that people limit consumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods such as those high in added sugars [7], with a suggested limit of between 5 and 15% per daily intake (2010 American Dietary Guidelines). Most people do not meet these dietary recommendations [8] and children and adolescents consume more calories from added sugars than adults [9] with many of these coming from sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) especially among adolescents [7, 10]. A recent meta-analysis and systematic review that examined results from 60 randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies concluded that increased dietary sugar intake was associated with increased body weight, while reduced dietary sugar intake was associated with decreased body weight [11]. With the ready availability of calorie-dense and high sugar foods, an understanding of patterns of consumption and overconsumption is increasingly important to support and enable weight regulation. One method of assisting weight regulation which has been proposed and explored in recent years is the utilization of mindfulness, self-compassion, and mindful eating.

A widely accepted definition of the practice of mindfulness is that it is an awareness that emerges through purposefully paying attention in the present moment, non-judgmentally [12]. The practice usually entails mindfulness meditation, which involves actively observing the present moment by attending to the breath, moment-to-moment, and accepting all experiences (such as feelings and thoughts) without adding any meaning to them. This helps people who observe the constant flow of information to systematically develop acceptance (instead of judgment), which may lead to further benefits such as compassion, equanimity, and other parts of mindfulness practice [13,14,15]. Recent psychological interventions have identified that self-compassion may be the most relevant construct within mindfulness in terms of assisting weight regulation and weight loss.

Self-compassion is a kinder approach toward oneself during personally challenging times, with a mindful awareness and understanding that one’s experiences are part of what all people go through (see Neff [16, 17] for review). Self-compassion consists of three main elements: self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness, combined, these elements create the construct of self-compassion (see Neff [17, 18]). Self-compassion is underexplored in the context of eating patterns and fat and sugar consumption. People who break their diet usually increase their subsequent food intake (see Herman and Mack [19]), and Adams and Leary [20] investigated this tendency in relation to self-compassion. In their research, this was not true for an experimental group that received a short self-compassionate induction to cope after the experience of breaking the diet. Following this work, further research has shown that self-compassion plays a significant role in maintaining weight (see Mantzios et al. [21]), in weight loss [22, 23], and with different practices (i.e., mindful diaries instead of meditation—see Mantzios and Wilson [24] and Hussein et al. [25]). Participants benefited from self-compassion by breaking the negative cycle of shame, body image dissatisfaction and the drive for thinness when investigating women with and without eating disorders [26]. These detrimental elements are also evident in dieting and overweight populations (e.g., [27,28,29]).

Mindfulness and self-compassion appear to complement each other in ways that translate into better outcomes for both mental and physiological health. Recent research conducted by Palmeira et al. [30] assessed the efficacy of a group intervention that incorporated mindfulness, compassion, and acceptance and commitment therapy approaches. Significant increases in health-related quality of life, reductions in unhealthy eating behaviors, and reductions in BMI in overweight and obese women were found. Research evidence also suggests that self-compassion explains the effectiveness of mindfulness practices. For example, people who scored higher in self-compassion experienced more benefits from training in mindfulness [31]. While well-being and stress are key determinants in eating behaviors and obesity [32, 33], research shows that self-compassion partially mediated the association between mindfulness and well-being [34], as well as mindfulness practice and stress [35]. Finally, when self-compassion was compared to mindfulness, research demonstrated that self-compassion was a more significant predictor of symptom severity in anxiety and depression [36], and further research has shown a clear association of anxiety and depression to obesity [37].

The psychological and physiological benefits from being more self-compassionate are evident and may be partially explained by the association between mindfulness and self-compassion and increased resiliency and tolerance to psychological distress. The experience of stress, anxiety, and depression are known to increase feelings of hunger and a preference for high fat and sugary foods [38]. A recent meta-analysis showed a positive link between self-compassion and healthy eating habits, as well as other non-food-related associations to healthier lifestyles [39]. Therefore, the indirect benefits of both mindfulness and self-compassion may be factors that can enable and enhance weight regulation (see Mantzios and Wilson [40]), and may well be predictive of fat and sugar consumption. The combination of mindfulness and eating has created a new imperative for researchers who are specifically interested in investigating eating and how well it conforms to the principles of mindfulness: namely mindful eating.

In a recent review, Mantzios and Wilson [40] suggested that the investigations and interventions need to be more explicit and specific to eating. Mindful eating is the application of mindfulness fundamentals to food-related experiences, that is, purposeful attention to the present moment with a non-judgment or accepting attitude. Mindful eating has been related to healthier eating [41], and has been suggested to drop fasting glucose levels, reduce the consumption of sweets [42], and assist weight loss through mindfulness-based interventions [43], whether mindful eating relates to less fat and sugar consumption has not been explored. Overall, research suggests that mindfulness, self-compassion and mindful eating leads to healthier decision making in health contexts (see e.g., Black et al. [44], Jordan et al. [41]), which may well translate to less fat and sugar consumption. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the relationship between mindfulness, mindful eating, self-compassion, and fat and sugar consumption.

Methods

Participants

634 students were recruited through an online invitation to take part in a study investigating eating behaviors. 88 participants were excluded from the sample as they did not meet the set body mass index (i.e., BMI < 18), which may have indicated the existence of an eating disorder; leaving a final sample of 546 undergraduate students. The sample (Mage = 21.2, SD = 5.6; MBMI = 24.7, SD = 5.5; 263 females) consisted of: White European (n = 362), South Asian (n = 12), Black (n = 38), Chinese (n = 37), and mixed ethnicity (n = 25), with (n = 67) not disclosed. Participants were recruited on a voluntary basis, and did not receive any course credits or financial rewards.

Materials

Participant information sheet

Participants were asked to report their age, gender, height, weight, ethnicity, smoking, and exercising habits.

Self-compassion scale (SCS; [16])

The SCS scale is a 26-item self-report measure. Responses range from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always), with overall scores ranging from 26 to 130. Sample items include ‘I try to be loving towards myself when I’m feeling emotional pain’ (i.e., self-kindness) and ‘When I’m down and out, I remind myself that there are lots of other people in the world feeling like I am’ (i.e., common humanity). The scale is composed of six subscales, with alphas of: self-kindness (α = 0.88), self-judgment (α = 0.87), common humanity (α = 0.85), isolation (α = 0.83), mindfulness (α = 0.82), and over-identification (α = 0.82). The present study produced an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95 for the total score.

Five-facet mindfulness questionnaire—short form (FFMQ-SF; [45])

The FFMQ-SF is a 24-item questionnaire measuring five main characteristics of mindfulness, and is based on the original 39-item version (FFMQ; [46]). Responses range from 1 (never or rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true), with total scores varying from 24 to 120. Sample items are ‘I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present moment’ (i.e., acting with awareness) and ‘usually when I have distressing thoughts or images I can just notice them without reacting’ (i.e., non-reactive), and higher scores indicate higher levels of mindfulness. The five measured facets produced an alpha: observing (α = 0.77), describing (α = 0.87), acting with awareness (α = 0.83), non-judging (α = 0.78), and non-reactivity (α = 0.77). The present study produced an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86 for the overall score.

Mindfulness eating scale (MES; [47])

The MES is a 28-item scale, and is combined with five subscales, with responses ranging from 1 (Never) to 4 (Usually), and overall scores varying from 28 to 112. Sample items include ‘I wish I could control my eating more easily’ (i.e., acceptance) and ‘I notice flavors and textures when I’m eating my food’ (i.e., awareness). Higher scores indicate higher levels of mindful eating. The five subscales produced an alpha of: acceptance (α = 0.91), awareness (α = 0.85), non-reactivity (α = 0.77), routine (0.81), distractibility (α = 0.90), and unstructured (0.73). The present study produced an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90 for the total score.

Three factor eating questionnaire—short form (TFEQ-R18; [48])

The TFEQ-R18 is an 18-item questionnaire and measures the concepts of restrained eating, emotional eating, and uncontrolled eating, and is based on the original 51-item version (TFEQ; [49]). It includes items such as ‘When I smell a delicious food, I find it very difficult to keep from eating, even if I have just finished a meal.’ (i.e., restrained eating) and ‘When I feel lonely, I console myself by eating’ (i.e. emotional eating). Responses range from 1 (definitely false) to 4 (definitely true), with overall scores ranging from 18 to 76. The three subscales produced an alpha of: restrained eating (α = 0.77), emotional eating (α = 0.40), and uncontrolled eating (α = 0.85). The present study produced an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83 for the overall score.

Dietary fat and free sugar—short questionnaire (DFS; [50])

The DFS is a 26-item questionnaire that measures dietary saturated fat and free sugar intake over the past 12 months. Response options range between ‘1 per month or less’ to ‘5 + per week’, and sample items include ‘fried chicken or chicken burgers’ and ‘doughnuts, pastries, croissants’, and overall scores range from 26 to 130. Higher scores indicating higher energy, fat, and sugar intake. The present study produced a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83.

Procedure and design

Convenience sampling was used to approach students attending a university in the West Midlands region of the United Kingdom to take part in the present study. Potential participants responded to an advertisement from various online invitations, and a link was provided for participants to click on, which directed them to a participant information form, consent form, and it was then followed by the demographic information page and the questionnaires. Once participants completed the study, they were directed to a debriefing form, which provided them with further information about the aim and purpose of the current study. Participants were also given the opportunity to record an arbitrary number, which would allow them to withdraw their data at a later stage and retain the anonymity of participation. Ethical approval was granted by the Ethical Committee based within the University.

Results

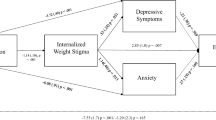

Inter-correlations between BMI, total fat and sugar consumption, self-compassion, mindfulness, and mindful eating are presented in Table 1. Findings suggest that there is a small significantly negative relationship between BMI and mindful eating [r = − 0.25, n = 546, p < 0.001]. In addition, small significant negative relationships are observed between total fat and sugar consumption, mindfulness [r = − 0.13, n = 489, p < 0.001], and mindful eating [r = − 0.12, n = 537, p < 0.001]. There are also large significant positive relationships between self-compassion, mindfulness [r = 0.65, n = 498, p < 0.001], and a moderate relationship with mindful eating [r = 0.38, n = 546, p < 0.001].

Inter-correlations between BMI, total fa,t and sugar consumption, mindfulness and mindful eating subscales are presented in Table 2. BMI displayed a small significant positive relationship with the observe subscale [r = 0.10, n = 540, p < 0.05] and a small significant negative relationship with the act with awareness subscale [r = − 0.12, n = 545, p < 0.001], both of which are subscales of the mindfulness scale. BMI also displayed a small significant negative relationship with acceptance [r = − 0.26, n = 545, p < 0.001], distractibility [r = − 0.23, n = 546, p < 0.001], and unstructured eating [r = − 0.13, n = 546, p < 0.001] subscales. Furthermore, there was a small significant negative relationship between total fat and sugar consumption and non-reactivity [r = − 0.20, n = 536, p < 0.001], distractibility [r = − 0.17, n = 537, p < 0.001], and unstructured eating [r = − 0.25, n = 537, < 0.001] subscales.

Inter-correlations between BMI, total fat and sugar consumption, and self-compassion subscales are presented in Table 3. There is a small significant negative relationship between BMI and isolation [r = − 0.09, n = 535, P < 0.05]. In addition, total fat and sugar consumption appears to have a small significant negative relationship to negative aspects of self-compassion (i.e., isolation and over-identification) [r = − 0.10, n = 526, p < 0.05] [r = − 0.10, n = 529, p < 0.05].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that explores cross-sectional constructs such as mindfulness, mindful eating, and self-compassion in relation to fat and sugar consumption. As suggested in previous research, eating-related constructs that are aligned with a mindful attitude (such as mindful eating) relate stronger to lower BMI than generic measures of mindfulness (e.g., Mantzios and Wilson [23]), as well as to decreased fat and sugar consumption. While mindfulness and self-compassion did not relate to higher levels of BMI, mindfulness appeared to be a slightly stronger correlate of lower fat and sugar consumption, while self-compassion showed no relationship at all. While literature is mixed in regards to the relationship of mindfulness and self-compassion to BMI, the data suggest that mindfulness as a construct is more consistent with constructs that describe healthier eating. The non-significant relationship of self-compassion may be attributable to elements discussed by Mantzios and Egan [51], whereby the self-compassion scale is not specific to health behaviors or eating. They further suggested that being kind to yourself does not guarantee both psychological and physiological health, and self-kindness may be expressed by eating or drinking unhealthy foods.

When findings were explored further, self-compassion subscales that related to fat and sugar consumption, as well as BMI were isolation and over-identification (i.e., the exact opposite of common humanity and mindfulness). In regards to mindfulness, observing and acting with awareness subscales, which are comparable to the mindful eating distractibility and unstructured eating subscales significantly related to BMI. The strongest correlation to BMI, however, was with the mindful eating acceptance subscale. In regards to fat and sugar consumption, the mindful eating distractibility and unstructured eating subscales, as well as the non-reactivity subscale significantly related to fat and/or sugar consumption.

Limitations

We identified three limitations to the present study. First, only university students were used in the present study; previous research has demonstrated that university students tend to not meet dietary guidelines, and exceed their daily fat and sugar intake [52,53,54]. Hence, caution should be taken when generalizing the findings toward other populations. Second, the average BMI was within the normal range, and findings could be significantly different amongst disordered eaters, dieters and obese participants. Obese participants were a minority within our sample, which made it difficult to develop further analyses and draw more conclusions. Closely aligned to this limitation is the weight and height which were self-reported and may have been misattributed. Third, the study presents cross-sectional data, which make further interpretations less robust. Future research should look into experimental and longitudinal studies, as well as clinical and community populations to explore the variation of fat and sugar consumption within mindfulness-based interventions, and allow causal and directional interpretations.

In addition, future research may also seek to explore the potential of intuitive eating and the association with fat and sugar consumption. Intuitive eating is distinct from mindful eating; however, there is a theoretical overlap between both constructs. Intuitive eating is often described as a ‘non-dieting approach’ similar to mindful eating, and emphasizes focus on internal hunger and fullness cues in addition to internal awareness and acceptance-related facets [55]. Differing from mindful practice, intuitive eating promotes altering cognitive distortions, emotional eating, and increasing shape acceptance [56]. Preliminary research has found that increased intuitive eating was related to improvements in emotional and physical health, and weight loss in obese women [57]. Other research has highlighted that intuitive eating was associated with lower BMI and decreased disordered eating patterns [58].

Conclusion

These data usefully add to our knowledge base; however, it requires multiple follow-up studies to investigate the quantity and the nature of third-wave constructs and interventions with fat and sugar consumption. The data also raise questions around the effectiveness of self-compassion when it comes to weight regulation. Despite the positive results that have been observed in other research [23, 40], it may be that self-compassion is better understood in the context of dieting, or, in relation to specific eating types (e.g., emotional or restrictive eating, see Adams and Leary [20]).

Although much research has focused on overeating, it is apparent that eating the wrong types of food has a similar detrimental effect on weight regulation. While this research serves as a platform to conduct further investigations, the necessity of exploring fat and sugar consumption in relation to the proposed constructs and aligned interventions is clear. Interventions for weight loss which rely on restriction may prove effective, at least in the short term, but are often not aligned with healthy eating and may foster feelings and behaviors, which are not aligned to mindful and compassionate being and living.

References

Drewnowski A (1989) Sensory preferences for fat and sugar in adolescence and adult life. Ann NY Acad Sci 561:243–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb20986.x

Drewnowski A, Popkin BM (1997) The nutrition transition: new trends in the global diet. Nutr Rev 55:31–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.1997.tb01593.x

Hu FB, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Ascherio A, Spiegelman D, Willett WC (2000) Prospective study of major dietary patterns and risk of coronary heart disease in men. Am J Clin Nutr 74:912–921

Popkin BM (2006) Global nutrition dynamics: the world is shifting rapidly toward a diet linked with noncommunicable diseases. Am J Clin Nutr 84:289–298

Mathers C, Fat DM, Boerma JT (2008) The global burden of disease: 2004 update. World Health Organization, Geneva

World Health Organization (2003) Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases: report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation. World Health Organization, Geneva

Gidding SS, Dennison BA, Birch LL, Daniels SR, Gilman MW, Lichtenstein AH, Rattay KT, Steinberger J, Stettler N, Horn LV (2006) Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents: a guide for practitioners. Pediatrics 117:544–559. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-2374

McGuire S (2011) US department of agriculture and US department of health and human services, dietary guidelines for Americans, 2010. Washington, DC: US government printing office, January 2011. Adv Nutr 2:293–294. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.111.000430

McGuire S, Ervin RB, Kit BK, Carroll MD, Ogden CL (2012) Consumption of added sugar among US children and adolescents, 2005–2008. NCHS data brief no 87. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. Adv Nutr 3:534. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.112.002279

Park S, Blanck HM, Sherry B, Brener N, O’Toole T (2012) Factors associated with sugar-sweetened beverage intake among United States high school students. J Nutr 142:306–312. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.111.148536

TeMorenga L, Mallard S, Mann J (2012) Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. Br Med J 346:e7492. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e7492

Kabat-Zinn J (1990) Full catastrophe living; how to cope with stress, pain and illness using mindful meditation. Little, Brown Book Group, London

Kabat-Zinn J (2006) Coming to our senses: healing ourselves and the world through mindfulness. Hyperion, New York

Grossman P, Van Dam NT (2011) Mindfulness, by any other name… trials and tribulations of sati in western psychology and science. Contemp Buddhism 12:219–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/14639947.2011.564841

Grossman P (2013) Kindness and compassion as integral to mindfulness—experiencing the knowable in a special way. In: Singer T, Bolz M (eds) Compassion: bridging practice and science. Max Planck Society, Munich, pp 192–207

Neff KD (2003) The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity 2:223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027

Neff KD (2003) Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity 2:85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

Neff KD (2011) Self-compassion, self-esteem, and well-being. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 5:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00330.x

Herman CP, Mack D (1975) Restrained and unrestrained eating. J Pers 43:647–660. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1975.tb00727.x

Adams CE, Leary MR (2007) Promoting self-compassionate attitudes towards eating among restrictive and guilty eaters. J Soc Clin Psychol 26:1120–1144. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2007.26.10.1120

Mantzios M, Wilson JC, Linnell M, Morris P (2014) The role of negative cognitions, intolerance of uncertainty, mindfulness, and self-compassion in weight regulation among male army recruits. Mindfulness 6:545–552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0286-2

Mantzios M, Giannou K (2014) Group vs. Single mindfulness meditation: exploring avoidance, impulsivity and weight management in two separate mindfulness meditation settings. Appl Psychol Heal Well Being 6(2):173–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12023

Mantzios M, Wilson JC (2015) Mindfulness, eating behaviours, and obesity: a review and reflection on current findings. Cur Obes Rep 4(1):141–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-014-0131-x

Mantzios M, Wilson JC (2014) Making concrete construals mindful: a novel approach for developing mindfulness and self-compassion to assist weight loss. Psychol Heal 29:422–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2013.863883

Hussein M, Egan H, Mantzios M (2017) Mindful construal diaries: a less anxious, more mindful, and more self-compassionate method of eating. Sage Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017704685

Ferreira C, Pinto-Gouveia J, Duarte C (2013) Self-compassion in the face of shame and body image dissatisfaction: Implications for eating disorders. Eat Behav 14(2):207–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.005

Chernyak Y, Lowe MR (2010) Motivations for dieting: drive for thinness is different from drive for objective thinness. J Abnorm Psychol 119:276–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018398

Conradt M, Dierk JM, Schlumberger P, Rauh E, Hebebrand J, Rief W (2008) Who copes well? Obesity-related coping and its associations with shame, guilt, and weight loss. J Clin Psychol 64:1129–1144. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20501

Gavin AR, Simon GE, Ludman EJ (2010) The association between obesity, depression, and educational attainment in women: the mediating role of body image dissatisfaction. J Psychosom Res 69:573–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.05.001

Palmeira L, Pinto-Gouveia J, Cunha M (2017) Exploring the efficacy of an acceptance, mindfulness and compassionate-based group intervention for women struggling with their weight (Kg-Free): a randomized controlled trial. Appetite 112(Supplement C):107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.01.027

Birnie K, Speca M, Carlson LE (2010) Exploring self-compassion and empathy in the context of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Stress Heal 26:359–371. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1305

Gall K, van Zutven K, Lindstrom J, Bentley C, Gratwick-Sarll K, Harrison C, Lewis L, Mond J (2016) Obesity and emotional well-being in adolescents: roles of body dissatisfaction, loss of control eating, and self-rated health. Obesity 24:837–842. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21428

Torres SJ, Nowson CA (2007) Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition 23:887–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2007.08.008

Hollis-Walker L, Colosimo K (2011) Mindfulness, self-compassion, and happiness in non-meditators: a theoretical and empirical examination. Personal Individ Diff 50:222–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.033

Shapiro SL, Astin JA, Bishop SR, Cordova M (2005) Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: results from a randomized trial. Int J Stress Manag 12:164–176. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.12.2.164

Van Dam NT, Sheppard SC, Forsyth JP, Earleywine M (2011) Self-compassion is a better predictor than mindfulness of symptom severity and quality of life in mixed anxiety and depression. J Anx Dis 25:123–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.08.011

Goossens L, Braet C, Van Vlierberghe L, Mels S (2009) Loss of control over eating in overweight youngsters: the role of anxiety, depression and emotional eating. Eur Eat Dis Rev 17:68–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.892

Dallman MF (2010) Stress-induced obesity and the emotional nervous system. Trends Endocrinol Metab 21:159–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2009.10.004

Sirois FM, Kitner R, Hirsch JK (2015) Self-compassion, affect, and health-promoting behaviours. Heal Psychol (APA) 34:661–669. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000158

Mantzios M, Wilson JC (2015) Exploring mindfulness and mindfulness with self-compassion-centered interventions to assist weight loss: theoretical considerations and preliminary results of a randomized pilot study. Mindfulness 6:824–835. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0325-z

Jordan CH, Wang W, Donatoni L, Meier BP (2014) Mindful eating: trait and state mindfulness predict healthier eating behavior. Personal Individ Diff 68:107–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.04.013

Mason AE, Epel ES, Kristeller J, Moran PJ, Dallman M, Lustig RH, Daubenmier J (2016) Effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on mindful eating, sweets consumption, and fasting glucose levels in obese adults: data from the SHINE randomized controlled trial. J Behav Med 39(2):201–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-015-9692-8

Mason AE, Epel ES, Aschbacher K, Lustig RH, Acree M, Kristeller J et al (2016) Reduced reward-driven eating accounts for the impact of a mindfulness-based diet and exercise intervention on weight loss: data from the SHINE randomized controlled trial. Appetite 100:86–93

Black DS, Sussman S, Johnson CA, Milam J (2012) Psychometric assessment of the mindful attention awareness scale (MAAS) among Chinese adolescents. Assessment 19:42–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191111415365

Bohlmeijer E, ten Klooster PM, Fledderus M, Veehof M, Baer R (2011) Psychometric properties of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in depressed adults and development of a short form. Assessment 18(3):308–320

Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L (2006) Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment 13(1):27–45

Hulbert-Williams L, Nicholls W, Joy J, Hulbert-Williams N (2014) Initial validation of the mindful eating scale. Mindfulness 5(6):719–729

Karlsson J, Persson LO, Sjöström L, Sullivan M (2000) Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) in obese men and women. Results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study. Int J Obes 24(12):1715

Stunkard AJ, Messick S (1985) The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res 29(1):71–83

Francis H, Stevenson R (2013) Validity and test–retest reliability of a short dietary questionnaire to assess intake of saturated fat and free sugars: a preliminary study. J Hum Nutr Diet 26(3):234–242

Mantzios M, Egan HH (2017) On the role of self-compassion and self-kindness in weight regulation and health behaviour change. Front Psychol 8:229. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00229

Papadaki A, Hondros G, Scott JA, Kapokefalou M (2007) Eating habits of University students living at, or away from home in Greece. Appetite 49(1):169–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2007.01.008

Anding JD, Suminski RR, Boss L (2010) Dietary intake, body mass index, exercise, and alcohol: are college women following the dietary guidelines for Americans? J Am Coll Heal 49(4):167–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480109596299

Huang TK, Harris KJ, Lee RE, Nazir N, Born W, Kaur H (2010) Assessing overweight, obesity, diet, and physical activity in college students. J Am Coll Heal 52(2):83–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480309595728

Anderson LM, Reilly EE, Schaumberg K, Dmochowski S, Anderson DA (2016) Contributions of mindful eating, intuitive eating, and restraint to BMI, disordered eating, and meal consumption in college students. Eat Weight Disord 21(1):83–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0210-3

Tribole E, Resch E (1995) Intuitive eating: a recovery book for the chronic dieter: rediscover the pleasures of eating and rebuild your body image

Bacon L, Stern JS, Van Loan MD, Keim NL (2005) Size acceptance and intuitive eating improve health for obese, female chronic dieters. J Am Diet Assoc 105(6):929–936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2005.03.011

Denny KN, Loth K, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D (2013) Intuitive eating in young adults. Who is doing it, and how is it related to disordered eating behaviors? Appetite 60:13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.09.029

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the University, and was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. Informed written consent was obtained prior to the experiment. This article does not contain any studies with animals.

Informed consent

All participants were provided with a participant information sheet which outlined the aims and objectives of the research, assured confidentiality and informed participants of their right to withdraw. Participants were provided with a participant number in order that they could contact the lead researcher for up to two weeks after completed the study if they wished to withdraw their data. Participants gave consent online by clicking a consent button once they had completed the study.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to public availability violating the consent that was given by research participants.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mantzios, M., Egan, H., Hussain, M. et al. Mindfulness, self-compassion, and mindful eating in relation to fat and sugar consumption: an exploratory investigation. Eat Weight Disord 23, 833–840 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0548-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0548-4