Abstract

Cognitive confidence, a type of metacognition referring to confidence in one’s cognitive abilities (e.g., memory, perception, etc.), has been identified as relevant to eating disorders (EDs) using self-report measures. Repeated checking has been found to elicit decreases in perceptual confidence in obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). The purpose of the present study was to experimentally investigate perceptual confidence, a type of cognitive confidence, in EDs. Specifically, this construct was investigated in the context of body checking, a behaviour with similarities to compulsive checking as observed in OCD. Women with bulimia nervosa (BN; n = 21) and healthy controls (HC; n = 24) participated in the study. There were no group differences with regards to perceptual confidence at baseline F(1, 43) = 0.5, p = 0.48, ηp2 = 0.01, but a significant difference was observed post-checking F(1, 43) = 7.79, p = 0.008, ηp2 = 0.15, which was accounted for by significant decreases in perceptual confidence in the BN group F(1, 43) = 13.31, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.24. Similar to compulsive checking in OCD, body checking may paradoxically decrease confidence regarding one’s appearance.

Level of Evidence

Level I, experimental study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Metacognition, referring to the beliefs held about one’s thoughts and cognitive processes, has emerged as a relevant construct in several psychiatric disorders [1]. Cognitive confidence is a form of metacognition pertaining to the degree of confidence one has regarding one’s cognitive abilities, including memory, reality monitoring, attention, and perception. Using self-report and experimental methods, considerable support has been found for the role of low cognitive confidence in obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), particularly with regards to compulsive checking. This line of research highlights a paradoxical relationship between compulsive checking and cognitive confidence, in that checking is performed to increase certainty, but actually seems to erode it [see 2 for a discussion]. Given its important role in compulsive checking in OCD, cognitive confidence warrants examination in other psychiatric disorders exhibiting similar behaviours.

In particular, compulsive checking in OCD is conceptually similar to body checking in eating disorders (EDs). Looking in the mirror repeatedly or for long periods of time, checking for ‘tightness’ in specific pieces of clothing, frequent weighing, and reassurance seeking are examples of body checking behaviours [3]. Body checking is a common clinical behaviour across EDs, with some research suggesting that it may be particularly prevalent in bulimia nervosa (BN) [4]. Of interest to the study of body checking is research demonstrating that perseverative attending (i.e., staring), as occurs in body checking, has also been found to elicit low perceptual confidence in non-clinical samples using OCD-relevant tasks [5, 6]. Perceptual confidence is a subtype of cognitive confidence referring to confidence in one’s perceptual abilities (usually visual).

As in OCD, body checking in EDs is often performed to increase certainty, but often paradoxically elicits adverse effects. In a study investigating attitudes towards body checking, it was found that this behaviour often provides short-term reassurance regarding weight, but generates distress in the long term [7]. Indeed, body checking has been found to increase the fear of fatness, body dissatisfaction, self-critical thoughts, and weight and shape concerns [8, 9]. Moreover, body checking has been identified as a maintenance factor for body image disturbance [10]. It may be that body checking elicits body dissatisfaction and low perceptual confidence, which may in turn promote more body checking, among other pathological behaviours and attitudes.

Several studies have found an association between low cognitive confidence and EDs [11,12,13,14,15]. These studies utilised the short form of the Metacognitions Questionnaire (MCQ-30) [16], a general measure of metacognition with a cognitive confidence subscale. To our knowledge, however, no study has evaluated cognitive confidence or any of its subtypes in EDs either through the use of a disorder-specific questionnaire or any experimental paradigm.

The present study aims to experimentally evaluate the role of perseverative attending to the body in the form of body checking and its impact on perceptual confidence. It is hypothesized that BN will be associated with decreased confidence in estimates of body size (i.e., decreased perceptual confidence) following a body checking task. It is also hypothesized that body checking will elicit increased body dissatisfaction in the BN group. Finally, the present study sought to evaluate perceptual confidence in EDs using a self-report questionnaire. It is hypothesized that individuals who engage in more body checking will also report lower perceptual confidence.

Method

Participants

Fifty participants (25 BN and 25 healthy control [HC] participants) were recruited from the community. Potential participants responded to advertisements on websites (ex: Kijiji®), social media (ex: Facebook®), a newspaper, and in universities. Inclusion criteria: (1) aged 18–45; and (2) primary diagnosis of BN (for BN group only). Exclusion criteria: (1) traumatic brain injury; (2) evidence of current or past schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or organic mental disorder; and (3) inability to read and/or understand either English or French. Exclusion criteria specific to the HC group were the presence of severe psychopathology, current ED, or history of an ED. To avoid creating an artificial HC group, however, several HC participants were admitted into the study despite reporting mild symptoms congruent with specific phobia (n = 2), panic attacks (n = 2), and generalized anxiety disorder (n = 1) during the phone evaluation. All participants in the BN group met full DSM 5 criteria for BN except for three participants, who instead met criteria for an ED not otherwise specified (EDNOS) as they demonstrated primarily subjective binge episodes. The following comorbid disorders were observed in the BN group: depression (n = 2), substance use disorder (n = 5), panic disorder (n = 1), specific phobia (n = 6), and generalized anxiety disorder (n = 3). Finally, 28% of participants in the BN group reported the use of psychoactive medications, 32% were receiving psychological treatment for an ED at the time of study participation, and another 52% reported past psychological treatment (20% for an ED and 32% for another reason). Participants were compensated financially for their time.

Four participants in the BN group did not complete the study for ethical reasons (participant unwillingness or distress). Furthermore, one of the HC participants was identified as an outlier; it was evident that this participant had systematically answered the lowest possible value on all measures of confidence pre- and post- body checking. Exclusion of this participant resulted in better model fit, but did not significantly alter main and interaction effects. The final sample consisted of 21 women with BN and 24 women in the HC group.

Measures

A pre-screening questionnaire [17] was used to evaluate the inclusion/exclusion criteria over the phone prior to entry into the study.

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID-I) [18] is a semi-structured interview used to diagnose Axis I disorders. When compared to other clinical interviews, the SCID-I has been found to have superior validity [19]. This interview was used to evaluate comorbid disorders in the BN group.

The Eating Disorders Examination (EDE) [20] is a clinician-administered semi-structured interview. This interview establishes the diagnosis of EDs by evaluating the presence or absence of relevant behavioural and cognitive symptoms for the preceding 3-month period. The reliability, discriminant validity, and internal consistency of the EDE are all excellent [20, 21]. Diagnostically relevant questions were assessed over the lifetime to confirm that the HC group did not have a history of an ED.

A Body Checking Task (BCT) was created for the purposes of the present study to evaluate whether perseverative attending, as is characteristic of body checking, results in decreased perceptual confidence regarding the size of the body. The BCT was comprised of two parts. Part 1: Participants were instructed to look into a mirror at specified body parts—arms, stomach, hips, and thighs—each for 15 s (to prevent them from spontaneously engaging in body checking behaviours). After the examination of a body part, participants were asked to estimate its circumference. Once all body parts were examined and estimates given, participants were asked to assess their confidence in the accuracy of their estimates (i.e., perceptual confidence) as well as their degree of body dissatisfaction regarding each of these body parts on visual analogue scales (VAS). Part 2: the body part rated as the least satisfactory during the first part of the task was selected for examination in the second part. Participants were instructed to examine the selected body part for a period of 10 min and were told that this was to gain more information about the nature of it. Participants were told they could examine the body part from different angles, touch it, and/or sit in a chair to see how it looked when sitting. Following this, participants were asked to re-assess their confidence in the accuracy of their initial estimates as well as their degree of dissatisfaction towards each body part. Decreases in confidence in the accuracy of the initial estimates suggests lower perceptual confidence following body checking.

The BCT is based on the low and high body checking conditions of the task used by Shafran et al. [9], which was validated as a manipulation of body dissatisfaction. The BCT differs in that participants were not asked to describe their bodies in a neutral manner in Part 1 (low checking condition) and the instructions to engage in body checking behaviours were presented as suggestions in Part 2 (high checking condition). These differences reflect that the purpose of the present study was to compare ‘normal’ versus perseverative body checking behaviours to evaluate the effects on perceptual confidence. The procedure for body size estimation was based on that used by Smeets et al. [22], designed with the aim of eliciting focus on a particular aspect of body checking, that is, the size of different body parts. The BCT builds on manipulation procedures utilised in these other tasks to test the hypothesis that increased focus on specific body parts, as is characteristic of prolonged checking, not only elicits body dissatisfaction, but also elicits decreased perceptual confidence as has been found in the OCD literature [5, 6]. For this reason, the overall structure of the BCT is based on the methodology of a study measuring the effects of perseverative checking in OCD [5]. As in the present study, van den Hout et al. asked participants to look at the stimulus for a few seconds, complete a measure of perceptual confidence, check the stimulus for 10 min, and complete a measure of perceptual confidence a second time [5].

Perceptual confidence (confidence in the accuracy of estimates of body part size during the BCT) was measured using a VAS (VAS-P) ranging from ‘not at all confident’ to ‘extremely confident’. Participants were asked to indicate their response by placing an “X” on a line measuring 10 cm. Body satisfaction was measured using a VAS (VAS-S) ranging from ‘not at all satisfied’ to ‘extremely satisfied’.

The Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26) [23] is a 26-item measure of the nature and severity of eating pathology on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from ‘always’ to ‘never’. The total score and each of the three subscales have demonstrated acceptable internal consistency in a bilingual sample with BN (α = 0.72–0.89) [24].

The Body Checking Questionnaire (BCQ) [10] is a 23-item self-report questionnaire that assesses a variety of body checking behaviours along a scale from 1 (‘never’) to 5 (‘very often’). The BCQ has also demonstrated excellent test–retest reliability (r = 0.94) and convergent validity when compared with other measures of negative body image and EDs [10]. The BCQ was administered to determine the degree of body checking outside of the laboratory-based BCT.

The Distrust of the Senses in Eating Disorders scale (DSED) is a 10-item self-report questionnaire developed using expert consensus for the purposes of the present study. The DSED assesses an individual’s confidence in their senses (visual and tactile senses as well as bodily signals). Items include ‘The way I perceive my body when I look in the mirror is accurate’ and ‘I trust that I am able to see what I look like in reality’. These items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘I do not doubt this at all’ to ‘I doubt this very strongly’ (with higher scores indicating more distrust, or put another way, less confidence). The DSED was administered to measure trait levels of perceptual confidence (i.e., doubt in perception abilities) and to complement the state levels measured by the laboratory-based BCT. The questions and Likert scale were influenced by the Brief Cognitive Confidence Questionnaire [2]. The DSED demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the current sample (α = 0.93).

Materials

Online survey software, SurveyMonkey®, was used to administer self-report questionnaires. Participants received a link to access these questionnaires via email.

Height was calculated in inches using a soft tape measure affixed to the wall. Weight was measured by a calibrated scale.

Procedure

Participants were screened over the telephone to ensure eligibility. Eligible participants were emailed a link to the consent form and completed the questionnaires online. Once the questionnaires were completed, participants were scheduled for an appointment in the laboratory. The EDE (both groups) and SCID-I (BN group only) interviews were administered by the experimenter (SW). Participants’ height and weight were also measured by the experimenter to determine body mass index (BMI). Following this, participants completed the BCT. Participants were then debriefed as to the purposes of the study. Throughout each step of the study, participants were monitored for signs of distress and deterioration. Participants were given contact information for the experimenter and other resources in the event that they experienced negative effects following the BCT.

Statistics

Upon inspection of the variable residuals, it was determined that the post-checking data were skewed. A natural logarithmic transformation was applied to all data.

Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the effect of body checking on two dependent variables that were each assessed both pre- and post- body checking: perceptual confidence (VAS-P) and body satisfaction (VAS-S). Group (BN vs. HC) was the independent variable.

Pearson bivariate correlations were conducted to examine the relation between perceptual confidence as measured by the VAS-P, general confidence in the senses as measured by the DSED, and checking behaviour as measured by the BCQ. A change score was calculated for perceptual confidence from pre- to post- checking.

Results

See Table 1 for means and standard deviations for demographic variables and questionnaires.

Perceptual confidence

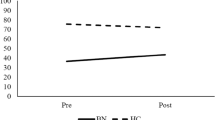

The omnibus test was significant and revealed a main effect of time F(1, 43) = 9.47, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.18 as well as a time by group interaction effect F(1, 43) = 5.07, p = 0.03, ηp2 = 0.11. Post hoc analyses indicated that there was no significant difference between groups with regards to perceptual confidence at baseline F(1, 43) = 0.5, p = 0.48, ηp2 = 0.01, but that there was a statistically significant difference between groups post-checking F(1, 43) = 7.79, p = 0.008, ηp2 = 0.15. Post hoc analyses also revealed that perceptual confidence in the BN group significantly decreased from pre- to post-checking F(1, 43) = 13.31, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.24, while no change was observed in the HC group F(1, 43) = 0.37, p = 0.55, ηp2 = 0.008. See Fig. 1.

An additional analysis was conducted to examine the potential role of comorbidity in the BN group on the results. There was no significant difference with regards to change in perceptual confidence from pre- to post-checking between BN participants with (n = 11) and BN participants without (n = 10) comorbid disorders t(19) = 1.11, p = 0.28.

Satisfaction

An independent samples t test revealed there was a significant difference between groups on degree of satisfaction pre- t(43) = − 6.26, p < 0.001, d = 1.89 and post-checking t(43) = − 5.38, p < 0.001, d = 1.64, with the BN group evincing significantly less body satisfaction. Repeated measures ANOVA was also used to assess the effect of body checking on degree of satisfaction. The omnibus test was non-significant indicating there was neither a main effect of time F(1, 43) = 0.06, p = 0.81, ηp2 = 0.001, nor was there a time by group interaction F(1, 43) = 0.23, p = 0.63, ηp2 = 0.005. See Fig. 2.

Correlations

The perceptual confidence change score was significantly correlated with the DSED (r = − 0.35, p = 0.019) and the BCQ (r = − 0.43, p = 0.003). Furthermore, the DSED and the BCQ were found to be significantly correlated with one another (r = 0.87, p < 0.001).

A statistically significant correlation was also observed between the severity of eating pathology, as measured by the EAT-26, and the change in perceptual confidence from pre- to post-checking (r = 0.49, p = 0.001).

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate body checking as a behaviour that may decrease perceptual confidence and ultimately increase body dissatisfaction. Results support the hypothesis that perseverative attending to the body during body checking elicits low perceptual confidence in individuals suffering from BN, but has no effect on participants without eating pathology. This finding is consistent with previous research that has found an association between perseverative attending and reduced perceptual confidence using OCD-relevant stimuli [5, 6] and points to the relevance of this association in body checking as well. Unlike previous studies [8, 9], however, body checking had no effect on body dissatisfaction either in the BN or HC groups. It is possible that this is due to a floor effect as satisfaction toward the body was already very low at baseline in the BN group. This finding also suggests that perceptual confidence and body dissatisfaction are distinct. Change in perceptual confidence was also significantly correlated with severity of eating pathology, validating the main findings of the study. Finally, there was no difference between participants in the BN group with and without comorbid disorders in terms of change in perceptual confidence, suggesting that the results are not better accounted for by comorbidity.

Regarding the novel self-report measure of perceptual confidence, correlational analyses suggest that larger decreases in confidence from pre- to post-checking are significantly correlated with higher scores on a measure of trait/habitual body checking and greater scores on a trait measure of perceptual confidence in ED-specific (body-related) situations. Furthermore, trait/habitual body checking and low perceptual confidence (as measured by the questionnaire) were significantly associated with one another. This result lends support to the experimental finding that increased body checking is related to decreased perceptual confidence. The lack of baseline differences in terms of confidence despite the correlation between the trait/habitual measures of body checking and questionnaire measure of perceptual confidence regarding the body may also imply that even though low perceptual confidence can be triggered by body checking, it is a temporary and fluctuating state. This is in line with previous research that has found that body image disturbance fluctuates across time and across contexts [25,26,27,28,29]. It is possible that reduced perceptual confidence elicited by body checking contributes in part to fluctuations in body image disturbance. The present study also has other important clinical implications as the results suggest that body checking may also elicit decreased perceptual confidence and certainty, which may in turn encourage further checking resulting in a vicious cycle. Indeed, the paradoxical and self-maintaining cycle of checking and the role of low cognitive confidence is already well documented in OCD [ex: 2].

The role of cognitive confidence in eating pathology represents an understudied area, however, there are several studies that have suggested the relevance of this construct, though using different terminology. Lautenbacher et al. [30] conducted a study using a body size estimation task in a non-clinical sample. They found significant differences in estimation accuracy between restrained (i.e., adhering to a diet) and unrestrained (i.e., eating in response to physiological cues) eaters, but determined that this effect was mainly driven by the unrestrained group. The authors concluded that uncertainty with regards to body size may have played an important role in this study. It was suggested that uncertainty may represent a predisposition that interacts with other cognitive and affective factors to elicit body size overestimation in EDs [30]. The uncertainty observed in this study may have been related to decreases in perceptual confidence elicited by the body estimation task. Perceptual confidence may help to explain inconsistent findings across experimental studies of perception using body size estimation tasks [31]. That is, overestimation of body size may be triggered by the experimental (body-focused) context and hence be accounted for by cognitive processes rather than actual perceptual deficits. Furthermore, Espeset et al. [32] found that body image disturbance is triggered by different contextual cues and that this susceptibility seems to be augmented by subjective uncertainty regarding the body’s appearance (potentially a manifestation of low perceptual confidence).

Treatment for EDs may benefit from the addition of interventions addressing perceptual, and possibly other forms of cognitive confidence, especially with individuals who engage in body checking. One particular treatment, termed inference based treatment (IBT), is designed to directly address doubt elicited in part by low confidence in sensory information in OCD [33]. Doubt and uncertainty are closely related, but distinct constructs. Doubt is uncertainty in the face of sensory information (‘I am looking in the mirror, but I’m unsure what I look like’) and so speaks directly to perceptual confidence, whereas uncertainty occurs in relation to circumstances about which one does not yet have information (‘In the future, I might become fat’). It was found that IBT adapted for EDs was associated with clinically significant decreases in eating pathology [34]. Addressing perceptual confidence in standard cognitive behavioural treatment for BN might involve targeting beliefs about one’s senses as well as body checking behaviours.

The present study has several limitations. Actual body size was not measured during the body checking task, which precluded the evaluation of body size estimation accuracy. This was done in an effort to obtain a pure measure of confidence in the perception of the body that would not be influenced by access to objective information (for example, learning the actual circumference of one’s waist may have elicited body dissatisfaction beyond the effects of body checking). Additionally, the absence of objective measurement is more in line with most body checking rituals (e.g., staring in the mirror, reassurance seeking, etc.). Another potential limitation is the absence of a control condition. Future studies with larger samples should incorporate a control condition into the study design to rule out the possibility that confidence decreases naturally over time following brief exposure to one’s body. Though a fairly small sample size was employed, the effect sizes obtained allow for confidence in the robustness of the effects observed. Another limitation was the presence of substantial comorbidity in the present sample, though the results indicate no difference in change in perceptual confidence between those with and without comorbidity. High rates of comorbidity also represent the clinical reality of EDs and their inclusion in the sample contributes toward the generalizability of the results obtained. Finally, though the questionnaire measuring perceptual confidence that was created for this study (DSED) demonstrated excellent internal consistency in this sample, it has not yet been validated. A targeted psychometric study using a larger sample size is required. The present study also had several strengths. Notably, the utilisation of self-report measures, semi-structured diagnostic interviews, and an experimental task allows for convergent validity and adds strength to the conclusions drawn from the results. Additionally, to our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate any form of cognitive confidence in EDs using an experimental paradigm.

References

Cartwright-Hatton S, Wells A (1997) Beliefs about worry and intrusions: the meta-cognitions questionnaire and its correlates. J Anxiety Disord 11:279–296

Hermans D, Engelen Y, Grouwels L, Joos E, Lemmens J, Pieters G (2008) Cognitive confidence in obsessive-compulsive disorder: distrusting perception, attention and memory. Behav Res Ther 46:98–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.11.001

Rosen JC (1997) Cognitive behavioural image therapy. In: Garner DM, Garfinkel PE (eds) Handbook of treatment for eating disorders, 2nd edn. Guilford, New York, pp 188–201

Kachani AT, Barroso LP, Brasiliano S, Hochgraf PB, Cordas TA (2014) Body checking and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in Brazilian outpatients with eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord 19:177–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-014-0111-x

van den Hout M, Engelhard IM, de Boer C, du Bois A, Dek E (2008) Perseverative and compulsive-like staring causes uncertainty about perception. Behav Res Ther 46:1300–1304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.09.002

van den Hout M, Engelhard IM, Smeets M, Dek ECP, Turksma K, Saric R (2009) Uncertainty about perception and dissociation after compulsive-like staring: time course of effects. Behav Res Ther 47:535–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.03.001

Meyer C, McPartlan L, Rawlinson A, Bunting J, Waller G (2011) Body-related behaviours and cognitions: relationship to eating psychopathology in non-clinical women and men. Behav Cogn Psychother 39:591–600. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465811000270

Shafran R, Fairburn CG, Robinson P, Lask B (2004) Body checking and its avoidance in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 35:93–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10228

Shafran R, Lee M, Payne E, Fairburn CG (2007) An experimental analysis of body checking. Behav Res Ther 45:113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.015

Reas DL, Whisenhunt BL, Netemeyer R, Williamson DA (2002) Development of the body checking questionnaire: a self-report measure of body checking behaviors. Int J Eat Disord 31:324–333. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10012

Cooper MJ, Grocutt E, Deepak K, Bailey E (2007) Metacognition in anorexia nervosa, dieting, and non-dieting controls: a preliminary investigation. Br J Clin Psychol 46:113–117. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466S06X11524S

Davenport E, Rushford N, Soon S, McDermott C (2015) Dysfunctional metacognition and drive for thinness in typical and atypical anorexia nervosa. J Eat Disord 3:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-015-0060-4

McDermott CJ, Rushford N (2011) Dysfunctional metacognitions in anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord 16:49–55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-015-0060-4

Olstad S, Solem S, Hjemdal O, Hagen R (2015) Metacognition in eating disorders: comparison of women with eating disorders, self-reported history of eating disorders or psychiatric problems, or healthy controls. Eat Behav 16:17–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.10.019

Vann A, Strodl E, Anderson E (2014) The transdiagnostic nature of metacognitions in women with eating disorders. Eat Disord 22:306–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2014.890447

Wells A, Cartwright-Hatton S (2004) A short-form of the metacognitions questionnaire: properties of the MCQ-30. Behav Res Ther 42:385–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00147-5

Kirouac C, Denis I, Fontaine A, Côté S (2006) Questionnaire sur la santé. Montréal, Centre de Recherche Fernand-Seguin. Hôpital Louis-H, Lafontaine

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon MG, Williams JB (1997) Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I DISORDERS (SCID-I). In: Clinician version. American Psychiatric, Washington

Grabill K, Merlo L, Duke D, Harford K, Storch EA (2008) Assessment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a review. J Anx Disord 22:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.01.012

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z (1993) The eating disorder examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT (eds) Binge eating: nature, assessment and treatment, 12th edn. Guilford, New York

Rizvi SL, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, Agras WS (2000) Test-retest reliability of the eating disorder examination. Int J Eat Disord 28(200011):311–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X28:3%3C311::AID-EAT8%3E3.0.CO;2-K

Smeets E, Tiggeman M, Kemps E, Mills JS, Hollitt S, Roefs A, Jansen A (2011) Body checking induces an attentional bias for body-related cues. Int J Eat Disord 44:50–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20776

Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE (1982) The eating attitudes test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med 12:871–878. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700049163

Groleau P, Steiger H, Bruce K, Israel M, Sycz L, Ouellette AS, Badawi G (2012) Childhood emotional abuse and eating symptoms in bulimic disorders: an examination of possible mediating variables. Int J Eat Disord 45:326–332. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20939

Cash TF (2002) The situational inventory of body-image dysphoria: Psychometric evidence and development of a short form. Int J Eat Disord 32:362–366. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10100

Cash TF, Fleming EC, Alindogan J, Steadman L, Whitehead A (2002) Beyond body image as a trait: the development and validation of the body image states scale. Eat Disord 10:103–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640260290081678

Melnyk SE, Cash TF, Janda LH (2004) Body image ups and downs: Prediction of intra-individual level and variability of women’s daily body image experiences. Body Image 1:225–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.03.003

Rudiger JA, Cash TF, Roehrig M, Thompson JK (2007) Day-to-day body-image states: prospective predictors of intra-individual level and variability. Body Image 4:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.11.004

Tiggeman M (2001) Person x situation interactions in body dissatisfaction. Int J Eat Disord 29:65–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(200101)29:1%3C65::AID-EAT10%3E3.0.CO;2-Y

Lautenbacher S, Thomas A, Roscher S, Strian F, Pirke KM, Krieg JC (1992) Body size perception and body satisfaction in restrained and unrestrained eaters. Behav Res Ther 30:243–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(92)90070-W

Cash TF, Deagle ED III (1997) The nature and extent of body image disturbances in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord 22:107–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199709)22:2%3C107::AID-EAT1%3E3.3.CO;2-Y

Espeset EMS, Gulliksen KS, Nordbo RHS, Skarderud F, Holte A (2012) Fluctuations of body images in anorexia nervosa: patients’ perceptions of contextual triggers. Clin Psychol Psychother 19:518–530. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.760

O’Connor K, Aardema F, Pélissier MC (2005) Beyond reasonable doubt: reasoning processes in obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. Wiley, Chichester

Purcell Lalonde M, O’Connor K (2015) Food for thought: Change in ego-dystonicity and fear of self in bulimia nervosa over the course of inference based treatment. J Psychol Clin Psychiatry 3:1–10. https://doi.org/10.15406/jpcpy.2015.03.00133

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Fonds de Recherche du Québec—Santé (#33663) and by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (#114905). The authors would also like to acknowledge the statistical support provided by Charles-Édouard Giguère, MSc.

Funding

This study was funded by the Fonds de Recherche du Québec—Santé (#33663) and by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (#114905).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wilson, S., Aardema, F. & O’Connor, K. What do I look like? Perceptual confidence in bulimia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord 25, 177–183 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0542-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0542-x