Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to identify the risk of eating disorders (ED) in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) compared to controls.

Methods

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that included women with well-defined PCOS and controls and used validated ED screening/diagnostic tools to measure mean ED score, prevalence of abnormal ED scores, and/or prevalence of specific ED diagnoses such as bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder.

Results

Eight studies, including 470 women with PCOS and 390 controls, met inclusion criteria for the systematic review. Meta-analysis of seven of those studies found that the odds of an abnormal ED score (OR 3.05; 95% CI 1.33, 6.99; four studies) and the odds of any ED diagnosis (OR 3.87; 95% CI 1.43, 10.49; four studies) were higher in women with PCOS compared to controls.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that women with PCOS are at increased odds of having abnormal ED scores and specific ED diagnoses. Given the potential implications of an ED on weight management strategies, our findings support routine screening for ED in this population.

Level of evidence

Level I, systematic review and meta-analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine disorder affecting up to 15 percent of reproductive age women [1]. Classic features include oligomenorrhea, hyperandrogenism, and polycystic-appearing ovaries on ultrasound [2, 3]. The co-morbidities associated with PCOS are well known and include an increased risk of obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, type II diabetes mellitus, and possibly cardiovascular disease [4]. Recent studies have highlighted the high prevalence of depressive (36.6%) and anxiety (41.2%) symptoms associated with PCOS, while other psychiatric disorders, such as eating disorders (ED), are not as well studied in relation to PCOS [5,6,7].

One ED is BED, a disorder characterized by excessive intake of food without subsequent purging, affecting approximately 2–3.5% percent of US adults and up to 30 percent of those in weight loss clinics [8,9,10]. The prevalence of anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN) is much lower, around 1% each in the U.S [9]. Other ED that do not fit into these diagnoses include the other specified feeding or eating disorders (OSFED), such as night eating syndrome (NES), and unspecified feeding and eating disorders (UFED) [11]. Regardless of the specific diagnosis, patients with ED have several features in common with women with PCOS. Both groups are at higher risk of depression and anxiety [5, 9], body image disturbances [12,13,14], and significant detrimental effects on quality of life [15, 16]. BED is particularly relevant to PCOS, as it is independently associated with diabetes mellitus, obesity, and hypertension, and all co-morbidities are also associated with PCOS [17]. Of note, weight management strategies may differ in women with BED given the need to minimize risk of exacerbating BED symptoms [18]. This is especially problematic in the PCOS population, as weight management is typically an integral part of the PCOS treatment paradigm for preventing downstream health consequences, augmenting fertility success, and ensuring management of symptoms such as hirsutism and acne [19]. Of note, women with PCOS often report that weight loss is more challenging for them than for women without PCOS [20]. This may place them at risk for disordered eating behaviors, such as severe restricting, binge eating, and/or inappropriate compensatory behaviors. Therefore, both the potential effect of ED on treatment of PCOS as well as the possible increased risk of ED in those with PCOS drive the need to evaluate the precise prevalence of ED in women with PCOS.

The current literature on this topic is sparse but small studies suggest that disordered eating is common among women with PCOS, with the prevalence ranging from 12 to 35% [6, 21]. This represents a significant gap in knowledge regarding the interaction between two conditions, namely PCOS and ED, which are common in women of reproductive age. Of note, in this study, the term “disordered eating” is diagnosed by a positive result on a screening assessment. This is in contrast to ED, which refers to the fulfillment of specific diagnostic criteria as described in DSM-V [11]. We performed this systematic review and meta-analysis to compare mean ED scores and determine the prevalence of disordered eating and specific ED diagnoses among women with well-defined PCOS compared to controls.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

An electronic literature search for articles addressing PCOS and ED was conducted by author I.L. in the following electronic databases up to the third week of January 2017: Ovid (MEDLINE and MEDLINE in-process and other non-indexed citations), EMBASE, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Reviews database (Table 1). Of note, terms such as “anorexia” and “bulimia” were used in addition to “anorexia nervosa” and “bulimia nervosa.” Performing the search with only these more specific terms resulted in a narrower pool of studies, and so the broader terms were used as well to avoid being overly restrictive. Data retrieval was limited to human studies. We did not apply any restrictions on language. Abstracts were considered if they included the necessary information.

Study selection and data extraction

Two authors (I.L. and S.S.) independently screened all queried studies for eligibility. If disagreement occurred on inclusion of a study, two additional authors (L.C. and A.D.) arbitrated the decision. All articles with comparisons of women with PCOS and controls who were screened for ED in general or AN, BN, or BED specifically were included. All participants with PCOS had diagnoses confirmed by Rotterdam or National Institutes of Health (NIH) criteria, the most widely accepted criteria for diagnosing PCOS [2, 3]. Controls were women who did not have symptoms of PCOS, either by participant self-report or by clinical evaluation as part of study protocol. Studies using either screening or diagnostic tools for ED were included, and an abnormal score was defined by the specific scale’s scoring criteria. In the study including data on NES, the diagnosis was based on the proposed research diagnostic criteria, as the description in the DSM-5 is not fully enumerated [6, 22]. Information on demographic variables, disordered eating scores, prevalence of ED, and odds ratios were collected when available. Studies that did not use Rotterdam or NIH criteria for the diagnosis of PCOS, included self-reported diagnoses of ED, or did not have a control group were excluded. If any data were missing, the authors were contacted to obtain the information.

For the meta-analysis portion of our study, articles that only reported mean ED scores, and not prevalence of ED or abnormal ED scores, were excluded unless the authors were able to provide the data when contacted. To include only high-quality studies, only those where diagnosis of PCOS was confirmed by the investigators, rather than self-report, were included in the meta-analysis. Studies were assessed by authors I.L. and L.C. for quality and bias using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) [23].

Data analysis

Random effect meta-analyses were used to estimate the pooled odds for disordered eating as well as the pooled odds for ED diagnoses in women with PCOS compared to controls. The metan command in STATA version 14.1 was used to construct the following forest plots: abnormally elevated ED score (based on individual screening or diagnostic tool guidelines), any ED (composite of diagnoses including BN, BED, AN, and NES), and each individual ED. When there were no events in either group, the study was excluded from the results of the meta-analysis. Chi-squared tests were used for the significance of the pooled odds ratio; I2 tests of heterogeneity were also applied. A funnel plot was created using the metafunnel command, in which the log OR of each study was plotted against the standard error of the log OR, to assess the potential presence of publication bias. In constructing the funnel plot, to be consistent with the metan command, zero cells were similarly treated by adding 0.5 to all cells of the 2 by 2 table. In addition, publication bias was tested using the Egger regression method, with a p-value < 0.05 suggesting the presence of bias (metabias command).

The meta-analysis was reported following the Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [24] and using the Metaanalysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines [25].

Results

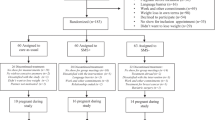

Figure 1 demonstrates the selection and review process. The initial search yielded a total of 261 articles. Of the 17 manuscripts that met our inclusion criteria, 2 were excluded for unsuitable control populations: in 1, controls were all hirsute from non-PCOS causes [26] and in another, controls all had AN [27]. Seven were excluded for inappropriate diagnostic criteria. In two studies, the diagnosis of PCOS was not based on Rotterdam or NIH criteria [28, 29]. In other studies, there was no description of diagnostic methods [30], only ultrasound appearance of ovaries was considered [31], or there was inclusion of luteinizing hormone (LH) levels [32], BMI [33], and LH/follicle-stimulating hormone ratio [34] as PCOS diagnostic criteria, which are not standard to the NIH and Rotterdam criteria. One study that was included in the systematic review used self-report of PCOS diagnosis with confirmation of Rotterdam criteria, but this was excluded from the meta-analysis due to the lack of clinician-determined diagnoses [35].

Eight studies were included in the systematic review (Table 2), capturing 470 women with PCOS and 390 controls. All studies were cross-sectional in design. The following ED scales were used in the included studies: Eating Attitudes Test-26 [36] and -40 [37], the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) [38], the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) [39], the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders Patient Health Questionnaire (PRIME-MD PHQ) [40], the Bulimic Investigatory Test Edinburgh (BITE) [41], the Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ) [42], and the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ-R21) [43]. Sensitivity and specificity data were reported only in the following: EAT-26 (for disordered eating, sensitivity: 88%; specificity: 96%) [44], MINI (sensitivity: 90% for AN, 99% for BN; specificity: 100% for AN, 99% for BN) [38], and EDE-Q (for disordered eating, sensitivity: 83%; specificity: 96%) [45]. Surveys composed by study investigators were included if they were based on the version of the DSM that was most recent at the time of the study’s publication [46].

Studies most commonly recruited participants with PCOS and controls from gynecology or fertility clinics and the community. In four studies, the two groups were recruited from different sites [6, 47,48,49]. In most studies, the mean age of both groups was between 25 and 35 years; however, only one study matched on age [47]. In five studies [6, 47,48,49,50], the women with PCOS had a significantly higher mean BMI than the control women. In our systematic review, five out of eight studies reported either a significantly higher mean ED score or a significantly higher prevalence of disordered eating in the PCOS group compared to the control group (Table 2). The NOS quality assessment of the studies included in both the systematic review and meta-analysis is presented in Supplemental Table 1; six studies were of medium quality, and two were of poor quality due to issues related to comparability of cases to controls (i.e. not age or BMI matched), representativeness of case subjects (e.g. there was a lack of description regarding the consecutiveness of recruitment), and non-response rate (most studies did not comment on the difference in survey non-response rate between groups).

In the meta-analysis, women with PCOS had higher odds of having abnormally elevated ED scores when compared to controls (OR 3.05; 95% CI 1.33, 6.99; four studies) (Fig. 2a), and there was no statistically significant heterogeneity among studies in this analysis (I2 = 56.3%, p = 0.076). This indicated that there was a little variation in outcomes among studies included in the meta-analysis. In three of the four studies, the women with PCOS had a higher mean BMI than the controls. Women with PCOS also had higher odds of having any ED diagnosis compared to controls (OR 3.87; 95% CI 1.43, 10.49; four studies) (Fig. 2b). There was no statistically significant heterogeneity among studies in this analysis (I2 = 49.7%, p = 0.113). Of the studies reporting the prevalence of specific ED diagnoses, only one used a diagnostic tool, the MINI [49]. The remaining studies used screening tools and assessed for fulfillment of diagnostic criteria based on the survey answers provided [6, 21, 47, 50]. In all studies, the women with PCOS had a higher mean BMI than the controls. No studies identified any cases of AN. The odds of BN (OR 2.23; 95% CI 0.66, 7.55; three studies, Fig. 2c; I2 = 37.3%, p = 0.203) and BED (OR 3.12; 95%CI 0.83, 11.75; two studies, Fig. 2d; I2 = 61.4%, p = 0.107) were increased but not statistically significantly different. No studies reported data on EDNOS or OSFED, other than NES in Lee and colleagues’ study [6], showing a similar prevalence among women with PCOS compared to controls (12.9 vs. 12.4%, p = 1.000).

To examine for evidence of bias, the funnel plots of the four studies included in our meta-analysis on the odds of abnormal ED scores and the four studies included on the odds of any ED diagnosis in women with PCOS are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The Egger test was not statistically significant for disordered eating (p = 0.912). The Egger test showed some publication bias in the meta-analysis of any ED (p = 0.043), suggesting that positive studies were more likely to be published, and smaller trials were more likely to show a robust association between PCOS and ED.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the prevalence of disordered eating as well as specific ED diagnoses in women with PCOS. In our meta-analysis including seven studies conducted in five countries, we report that women with PCOS have over three times the odds of having abnormal ED scores as well as being diagnosed with an ED when compared to women without PCOS. We found an increased prevalence for BN and BED, though this was not statistically significant, likely due to the low prevalence of these disorders in the general population and overall small numbers of subjects in each study. In a recent large Swedish population-based study, there was an increased prevalence of any ED [adjusted OR (aOR) 1.18; 95% CI 1.08, 1.29] and bulimia nervosa [aOR 1.21; 95% CI 1.03, 1.41] after adjusting for comorbidity with any other psychiatric disorder, consistent with our main findings [5]. Our findings suggest the need for screening women with PCOS for ED to counsel them appropriately regarding long-term medical and weight management.

To enhance the quality of all included studies, we applied contemporary Rotterdam or NIH criteria for diagnosis of PCOS, confirmed that controls did not have PCOS, and included studies that used validated ED screening or diagnostic tools. Previous studies have examined associations between disordered eating and polycystic ovaries [32] or testosterone levels [51] alone, rather than well-defined PCOS. Our meta-analysis includes a large number of subjects across many countries and shows an increased prevalence of disordered eating and ED despite using a variety of screening tools. One limitation of the studies included in our meta-analysis is that only one study used a diagnostic tool for ED (MINI) [49]. While we recommend that future studies should utilize diagnostic tools such as the MINI or a psychiatric interview to better validate the ED diagnoses, it is reassuring that in spite of the variation in assessment method, our results were largely consistent across studies. Given the low prevalence of ED in the general population and the moderate heterogeneity among studies in the two meta-analyses performed, larger studies are needed to evaluate the prevalence of ED diagnosis in women with PCOS.

We were unable to evaluate causality or chronicity between ED and PCOS as our analysis only included cross-sectional studies. In the current literature, there is only one study that has examined longitudinal prevalence of ED in women with PCOS, but it only included BED [52]. In addition, we were unable to evaluate the impact of anxiety and depression on the prevalence of disordered eating in PCOS. In the general population, there is an association between ED and anxiety and depression [9]. For example, up to 50% of individuals with a lifetime diagnosis of BN and 32% with BED have also experienced major depression, and close to 12% of those with BN or BED also have generalized anxiety disorder [9]. Only one study included in our meta-analysis examined this relationship and reported that elevated depressive (OR 5.43; 95% CI 1.85, 15.88) and anxiety (OR 6.60; 95% CI 2.45, 17.76) scores were associated with an increased odds of disordered eating [6]. After controlling for age and BMI, participants with PCOS and elevated anxiety scores also had an increased risk of disordered eating compared to those without elevated anxiety scores (aOR 5.91; 95% CI 0.61, 56.9). In addition, the large population-based study from Sweden reported an increased risk of BN among women with PCOS, even after controlling for psychiatric comorbidity (aOR 1.21; 95% CI 1.03, 1.41) [5].

It is well recognized that the prevalence of ED, particularly BED, increases with obesity [9]. In most of the studies included in the meta-analysis, subjects with PCOS had a higher mean BMI than the controls. However, two of these studies reported significantly increased odds of disordered eating even after adjusting for age and BMI (aOR 4.67; 95% CI 1.16, 18.8) [6] or a higher mean total Eating Attitudes Test (EAT) score after adjusting for BMI (adjusted p-value 0.001) [50]. Also, one study included in the systematic review reported that lean women with PCOS had significantly higher mean binge eating symptom scores than lean controls [35]. Thus, obesity alone likely does not explain the entire relationship between PCOS and ED. In addition, though differences in location of recruitment can pose a selection bias, three of the four studies that recruited all subjects from the same location reported higher mean ED scores or a higher prevalence of ED diagnoses in women with PCOS, supporting our overall findings.

While the causality of the increased prevalence of disordered eating and ED diagnoses associated with PCOS is unclear, women with PCOS have several risk factors for the development of ED, including body dissatisfaction, eating and weight concerns [53], cognitive restraint over eating, depressive symptoms [7], and higher BMI. Dieting in response to these risk factors seems to predict the onset of ED, and in one study, dieters at 5-year follow-up were significantly more likely to exhibit self-induced vomiting and laxative use as well as be obese [54].

Clearly establishing the relationship between ED and PCOS is of twofold importance. On the one hand, it is plausible that disordered eating may make management of PCOS symptoms more difficult. Weight gain is the most frequent concern for women with PCOS, and significant difficulties with weight management decrease quality of life in this population [53]. Identifying disordered eating in a proportion of women with PCOS will allow alternate strategies for management. On the other, although the etiology of ED in PCOS is unknown, it is possible that chronic dietary restraint, usually recommended from an early age for weight control in women with PCOS, may increase the risk of ED in this population.

The effect of concurrent ED on PCOS symptomatology and outcomes is especially pertinent as the prevalence of obesity is high (50–70%) in PCOS, and weight management is the most common PCOS-related concern in patients [53]. Women with ED, particularly BED, are generally heavier than their healthy counterparts [9]. In addition, in the general population, patients with BED seeking weight loss are less successful, regain weight more rapidly, and have higher attrition rates from treatment programs than those without BED [54]. In a study of 131 participants with obesity undergoing a lifestyle change program for weight loss, only 27% of patients with both major depression and BED achieved clinically significant weight loss compared with 67% of patients who had neither disorder [54]. This highlights the point that in those with a psychiatric history that may affect their weight, the typical prescription for weight loss—changes in diet and activity—may not be enough. Furthermore, there is evidence that addressing the underlying psychopathology may facilitate and augment weight loss. Individuals with obesity and BED who undergo cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and successfully stop binge eating during treatment lose more weight than those who do not and are more likely to maintain their weight loss [55]. Among women with PCOS and a comorbid mood disorder (depression, anxiety), CBT along with lifestyle changes results in significantly more weight loss than lifestyle changes alone [56]. Such a method has not been studied in women with PCOS and a comorbid ED, but it is plausible that approaching weight loss in a way that also addresses the underlying psychological concerns would be more successful. Our finding that disordered eating is more prevalent in women with PCOS suggests that routinely screening for ED could change the optimal weight management strategy for a large proportion of women with PCOS who are struggling to attain a healthy weight.

While it is undeniably important to promote weight management in women with PCOS given its positive impact on insulin sensitivity and reproductive function, the potential paradoxical harm in overemphasizing the value of weight loss cannot be dismissed. Even among pediatricians, who often detect ED and manage complications of obesity in adolescents, there is a shift towards taking care not to enable excessive dieting, compulsive exercise, and other unhealthy weight management strategies inadvertently [57]. The pressure to lose weight comes from many sources—for example, increased exposure to media is associated with increased ED symptoms, and this effect is mediated by gender-role endorsement, ideal body stereotype internalization, and body dissatisfaction [58]. Many of these mediating factors can also be seen as undercurrents of the physician’s encouragement to lose weight. Particularly in women with PCOS, weight loss as a means to improved fertility could be perceived as a type of gender-role endorsement, strong encouragement from a medical professional to lose weight could be perceived as idealization of a particular body type, and repeatedly being told that they have overweight/obesity could reinforce body dissatisfaction. This presents a challenging balance in the long-term care of women with PCOS where lifestyle modifications leading to weight loss are the first-line therapy in women who have PCOS and have overweight/obesity. Taking a more measured approach to weight management in women with both PCOS and an ED may avoid achieving a “healthy” weight at the cost of mental health and quality of life.

The Androgen Excess-PCOS Society guidelines from 2018 state that “disordered eating may be routinely screened in all women with PCOS at diagnosis using screening tools validated in the region of practice. If the screen is positive, practitioners should further assess, refer appropriately, or offer treatment” [59]. Our systematic review and meta-analysis, which includes several studies published after 2011, demonstrate an increased risk of both abnormal ED scores and ED diagnoses in women with PCOS. These findings suggest the need for screening women with PCOS for ED, especially in women with overweight/obesity, before initiation of weight management as part of PCOS treatment. It is clear that the presence of ED and PCOS together creates a unique and challenging predicament for successfully achieving sometimes conflicting goals of weight loss and psychiatric well-being, and will require a collaborative multidisciplinary effort including PCOS providers, mental health professionals, and clinical nutritionists. Screening during routine clinic visits can be cumbersome and time-consuming, but the Eating Disorder Screen for Primary Care (ESP) has been proposed as an efficient five-question tool that can help decide whether further assessment or referral is warranted [60]. Larger studies are needed to identify the independent association between ED and PCOS, and longitudinal studies should evaluate causality and persistent risk.

References

Lizneva D, Suturna L, Walker W, Brakta S, Gavrilova-Jordan L, Azziz R (2016) Criteria, prevalence, and phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 106:6–15. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0391-1977.18.02824-9

Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS, Consensus Workshop Group (2004) Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 81:19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004

Zawadski JK, Dunaif A (1992) Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: towards a rational approach. In: Dunaif A, Givens JR, Haseltine F (eds) polycystic ovary syndrome. Blackwell Scientific, Boston, pp 377–384

Dokras A (2013) Cardiovascular disease risk in women with PCOS. Steroids 78:773–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.steroids.2013.04.009

Cesta CE, Månsson M, Palm C, Lichtenstein P, Iliadou AN, Landén M (2016) Polycystic ovary syndrome and psychiatric disorders: co-morbidity and heritability in a nationwide Swedish cohort. Psychoneuroendocrinology 73:196–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.08.005

Lee I, Cooney LG, Saini S, Smith ME, Sammel MD, Allison KC, Dokras A (2017) Increased risk of disordered eating in polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 107:796–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.12.014

Dokras A, Clifton S, Futterweit W, Wild R (2011) Increased risk for abnormal depression scores in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Obstet Gynecol 117:145–152. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e318202b0a4

Grucza RA, Przybeck TR, Cloninger CR (2007) Prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in a community sample. Compr Psychiatry 48:124–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.08.002

Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, Kessler RC (2007) The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiat 1:348–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

Hudson JI, Coit CE, Lalonde JK, Pope HG Jr (2012) By how much will the proposed new DSM-5 criteria increase the prevalence of binge eating disorder? Int J Eat Disord 45:139–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20890

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington

Brechan I, Kvalem IL (2015) Relationship between body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: mediating role of self-esteem and depression. Eat Behav 17:49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.12.008

Himelein MJ, Thatcher SS (2006) Depression and body image among women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Health Psychology 11:613–625. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105306065021

Stice E, Shaw HE (2002) Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: a synthesis of research findings. J Psychosom Res 53:985–993. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00488-9

Cooney LG, Lee I, Sammel MD, Dokras A (2017) High prevalence of moderate and severe depressive and anxiety symptoms in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod 32:1075–1091. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dex044

de la Rie SM, Noordenbos G, van Furth EF (2005) Quality of life and eating disorders. Qual Life Res 14:1511–1522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-005-0585-0

Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Chiu WT, Deitz AC, Hudson JI, Shahly V, Xavier M (2013) The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biol Psychiat 1:904–914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.020

Palavras MA, Hay P, Touyz S, Sainsbury A, da Luz F, Swinbourne J, Estella NM, Claudino A (2015) Comparing cognitive behavioural therapy for eating disorders integrated with behavioural weight loss therapy to cognitive behavioural therapy-enhanced alone in overweight or obese people with bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 16:578. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-1079-1

Moran L, Gibson-Helm M, Teede H, Deeks A (2010) Polycystic ovary syndrome: a biopsychosocial understanding in young women to improve knowledge and treatment options. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 31:24–31. https://doi.org/10.3109/01674820903477593

McCuen-Wurst CM, Culnan E, Stewart NL, Allison KC (2018) Weight and eating concerns in women’s reproductive health. Curr Psychiatry Rep. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0828-0 (in press)

Karacan E, Caglar GS, Gürsoy AY, Yilmaz MB (2014) Body satisfaction and eating attitudes among girls and young women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 27:72–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2013.08.003

Allison KC, Lundgren JD, O’Reardon JP, Geliebter A, Gluck ME, Vinai P, Stunkard AJ (2010) Proposed diagnostic criteria for night eating syndrome. Int J Eat Disord 43:241–247. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20693

Wells GA, Shea B, Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M et al (1999) The Newcastle- Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Health Research Institute, Ottawa. Retrieved from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group (2010) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 8:336–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D et al (2010) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. J Am Med Assoc 283:2008–2012. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.15.2008

Morgan J, Scholtz S, Lacey H, Conway G (2008) The prevalence of eating disorders in women with facial hirsutism: an epidemiological cohort study. Int J Eat Disord 41:427–431. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20527

Pinhas-Hamiel O, Pilpel N, Carel C, Singer S (2006) Clinical and laboratory characteristics of adolescents with both polycystic ovary disease and anorexia nervosa. Fertil Steril 85:1849–1851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.11.041

Rodino IS, Byrne S, Sanders KA (2016) Disordered eating attitudes and exercise in women undergoing fertility treatment. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 56:82–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12407

Rodino IS, Byrne S, Sanders KA (2016) Obesity and psychological wellbeing in patients undergoing fertility treatment. Reprod BioMed Online 32:104–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.10.002

Resch M, Szendei G, Haász P (2004) Bulimia from a gynecological view: hormonal changes. J Obstet Gynaecol 24:907–910. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443610400018924

Morgan JF, McCluskey SE, Brunton JN, Lacey JH (2002) Polycystic ovarian morphology and bulimia nervosa: a 9-year follow-up study. Fertil Steril 77:928–931. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03063-7

McCluskey S, Evans C, Lacey JH, Pearce JM, Jacobs H (1991) Polycystic ovary syndrome and bulimia. Fertil Steril 55:287–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(16)54117-X

Michelmore KF, Balen AH, Dunger DB, Vessey MP (1999) Polycystic ovaries and associated clinical and biochemical features in young women. Clin Endocrinol 51:779–786. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00886.x

Jahanfar SH, Maleki H, Mosavi AR (2005) Subclinical eating disorder, polycystic ovary syndrome—is there any connection between these two conditions through leptin—a twin study. Med J Malaysia 60:441–446

Jeanes YM, Reeves S, Gibson EL, Piggott C, May VA, Hart KH (2017) Binge eating behaviours and food cravings in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Appetite 109:24–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.11.010

Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE (1982) The eating attitudes test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med 12:871–878

Garner DM, Garfinkel PE (1979) The eating attitudes test: an index of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med 9:273–279

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, … Dunbar GC (1998) The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 59(Suppl 20):22–33

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, O’Connor M (2008) Eating disorder examination, 16th edn. In: Fairburn CG (ed) Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guildford Press, New York

Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, Hornyak R, McMurray J (2000) Validity and utility of the PRIME-MD patient health questionnaire in assessment of 3000 obstetric-gynecologic patients: the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire Obstetrics-Gynecology Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 183:759–769. https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2000.106580

Henderson M, Freeman CP (1987) A self-rating scale for bulimia. The ‘BITE’. Br J Psychiatry 150:18–24

Allison KC, Lundgren JD, O’Reardon JP, Martino NS, Sarwer DB, Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ (2008) The Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ): psychometric properties of a measure of severity of the night eating syndrome. Eat Behav 9:62–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.03.007

Stunkard AJ, Messick S (1985) The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res 29:71–83

Mann AH, Wakeling A, Wood K, Monck E, Dobbs R, Szmukler G (1983) Screening for abnormal eating attitudes and psychiatric morbidity in an unselected population of 15-year-old schoolgirls. Psychol Med 13:573–580

Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJ (2004) Validity of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in screening for eating disorders in community samples. Behav Res Ther 42:551–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00161-X

Batcheller AE, Ressler IB, Sroga JM, Martinez AM, Thomas MA, DiPaola KB (2013) Binge eating disorder in the infertile polycystic ovary syndrome patient. Fertil Steril 100(Suppl 3):S413

Bernadett M, Szemán-N A (2016) Prevalence of eating disorders among women with polycystic ovary syndrome. [Article in Hungarian]. Psychiatria Hungarica 31:136–145

Hollinrake E, Abreu A, Maifeld M, Van Voorhis BJ, Dokras A (2007) Increased risk of depressive disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 87:1369–1376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.039

Månsson M, Holte J, Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Dahlgren E, Johansson A, Landén M (2008) Women with polycystic ovary syndrome are often depressed or anxious—a case control study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 33:1132–1138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.06.003

Larsson I, Hulthén L, Landén M, Pålsson E, Janson P, Stener-Victorin E (2016) Dietary intake, resting energy expenditure, and eating behavior in women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Nutr 35:213–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2015.02.006

Sundblad C, Bergman L, Eriksson E (1994) High levels of free testosterone in women with bulimia nervosa. Acta Psychiatr Scand 90:397–398

Kerchner A, Lester W, Stuart SP, Dokras A (2009) Risk of depression and other mental health disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a longitudinal study. Fertil Steril 91:207–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.11.022

Gibson-Helm M, Teede H, Dunaif A, Dokras A (2016) Delayed diagnosis and a lack of information associated with dissatisfaction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102:604–612. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-2963

Pagoto S, Bodenlos JS, Kantor L, Gitkind M, Curtin C, Ma Y (2007) Association of major depression and binge eating disorder with weight loss in a clinical setting. Obesity 15:2557–2559. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.307

Agras WS, Telch CF, Arnow B, Eldredge, KWilfley, DE, Raeburn SD… Marnell M (1994) Weight loss, cognitive-behavioral, and despiramine treatments in binge eating disorder. An additive design. Behav Ther 25:225–238

Cooney L, Milman LW, Sammel M, Allison KC, Epperson A, Dokras A (2016) Cognitive behavioral therapy improves weight loss and quality of life in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Fertil Steril 106:e252–e253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.07.729

Rosen DS (2010) Identification and management of eating disorders in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 126:1240–1253. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-2821

Stice E, Schupak-Neuberg E, Shaw HE, Stein RI (1994) Relation of media exposure to eating disorder symptomatology: an examination of mediating mechanisms. J Abnorm Psychol 103:836–840

Dokras A, Stener-Victorin E, Yildiz BO, Li R, Ottey S, Teede H (2018) Androgen excess-polycystic ovary syndrome: position statement on depression, anxiety, quality of life, and eating disorders in polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 109:888–899

Cotton M, Ball C, Robinson P (2003) Four simple questions can help screen for eating disorders. J Gen Intern Med 18:53–56. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20374.x

Funding

No specific funding was provided for this project. Laura Cooney was supported by a T32 Reproductive Training Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from each of the individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

40519_2018_533_MOESM1_ESM.tiff

Supplementary material 1: Supp. Figure 1 Evaluation of publication bias. 1a: funnel plot for studies reporting prevalence of any eating disorder to; 1b: funnel plot for studies reporting prevalence of disordered eating (Created using Stata). (TIFF 32874 KB)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, I., Cooney, L.G., Saini, S. et al. Increased odds of disordered eating in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat Weight Disord 24, 787–797 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0533-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0533-y