Abstract

Purpose

This study examined whether engagement in negative body talk would moderate the association between fear of fat and restrained eating among female friend dyads.

Methods

Female friends (Npairs = 130) were recruited from a Midwestern university in the United States. The dyadic data were examined with an Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM).

Results

Results showed that women’s fear of fat was significantly related to their own restrained eating behaviors. In contrast, women’s fear of fat was not significantly related to their friends’ restrained eating behaviors. Negative body talk was significantly related to restrained eating, as reported by both friends. The interaction between negative body talk and women’s own fear of fat was found to be significant. Although women with less fear of fat showed less restrained eating, engaging in more negative body talk with a friend increased their engagement in restrained eating. Women with more fear of fat engaged in more restrained eating, regardless of their engagement in negative body talk.

Conclusion

Given the detrimental role of body talk between fear of fat and restrained eating, interventions may target reducing body talk among young women.

No level of evidence for

Basic science, Animal study, Cadaver study, and Experimental study articles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Throughout their lives, women are socialized to place high value on physical attractiveness and are pressured to achieve and maintain a slim body [1,2,3]. Not surprisingly, women are vulnerable to experiencing fear of being overweight or gaining weight, or fear of fat [4]. This fear is an important component of the diagnostic for clinical eating disorders [5]. One notable consequence of fear of fat is restrained eating, a pattern of eating behaviors that encompasses intentions to control or restrict food intake to maintain or lose weight [6,7,8].

Numerous studies have provided evidence to support the interpersonal etiology of dietary restraint in women, especially the influences of peer relationships and negative body talk (e.g., [9]). Negative body talk refers to the interpersonal discussion of body image or weight-related issues [10]. Individuals who engage in negative body talk have more body image disturbances (e.g., fear of fat) and eating pathology (e.g., restrained eating; [11]). Yet, no work to our knowledge has examined how negative body talk relates to fear of fat and restrained eating among female friends. Thus, the primary goal of the current study is to directly examine negative body talk in female friends and how it may moderate the association between fear of fat and restrained eating.

Fear of fat and restrained eating

Fear of fat refers to individuals’ anxiety over the idea of gaining weight or being overweight, which often stems from the fear of acquiring negative stigmas and identity associated with overweight status [12]. Fear of fat is prevalent, affecting women regardless of age and cultural background [13]. Indeed, research indicates that girls as young as 5 years of age report being afraid of gaining weight, highlighting the pervasive and all-encompassing nature of fear of fat among women [14]. Furthermore, fear of fat has a strong motivational component that drives women to engage in dysfunctional eating behaviors [5, 12]. For instance, fear of fat has been shown to be related to more dietary restraint among college women [12, 15]. Extending this idea, research indicates that individuals who have been stigmatized based on weight also experience a more intense fear of fat, which is, in turn, related to more restrained eating behaviors [16]. Furthermore, a large-scale study of adolescent girls revealed fear of fat to be one of the strongest indicators of bulimic symptomology [17]. For these reasons, researchers have argued that fear of fat is an especially important construct to examine in women to make meaningful strides in promoting healthy eating behaviors and to further our understanding of pathological eating [4].

Negative body talk

Negative body talk is an interpersonal interaction that refers to the discussion of body image or weight-related issues in close relationships [10]. Body talk is especially common among adolescent girls and young adult women and typically involves friends speaking negatively about the size and shape of their own bodies [11, 18]. A recent review shows that experimental and correlational studies consistently suggest that individuals who engage in more negative body talk tend to suffer from more weight concerns and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors [11]. For instance, adolescents and young adults who engage in more body talk experience more body dissatisfaction, more pressure to be thin, lower self-esteem, and more depressive symptoms [19, 20]. Furthermore, individuals who engage in more negative body talk are also at risk for unhealthy dieting and restrained eating behaviors [21, 22].

Despite increased attention to the construct of negative body talk and its associations with weight concerns and pathological eating behaviors [11], there are two noteworthy gaps in the existing literature. First, although body talk is an interpersonal interaction that involves two partners (e.g., friends and couples), most existing studies examine this construct using one partner’s self-reports, with only a few studies examining the perspectives of both partners (e.g., Arroyo et al. [23]; Chow and Tan [24]; Tan and Chow [18]). Second, although negative body talk appears to be related to more weight concerns and pathological eating behaviors, the existing research has focused solely on examining direct associations among these variables. Little is known about how negative body talk may moderate the association between weight concerns (i.e., fear of fat) and pathological eating behaviors (i.e., restrained eating).

Moderating role of negative body talk

One possible moderating role of negative body talk among female friends would be to exacerbate the associations between fear of fat and restrained eating. Because body talk involves friends sharing and sometimes co-ruminating on body-related issues and negative emotions [25, 26], it is possible that fear of fat may be mutually reinforced and amplified between friends over time. It is also possible that social comparison occurs during body talk, enabling women to verbalize their concerns about looking worse than a self-selected standard [27]. The social comparison process may further exacerbate the existing negative body image and thus impact individuals’ efforts to manage their weight. Based on these arguments, friend dyads who engage in more body talk may be more likely to engage in restrained eating, especially if their fear of fat is also more pronounced. Even for women with positive or neutral body image, having a friend who engages in body talk may put pressure on them to reciprocate negative body talk. They may feel compelled to engage in negative body talk, leading to more body dissatisfaction and accompanying negative outcomes through repeated discussion [11].

An alternative argument, however, might suggest that the moderating role of negative body talk in female friends would be to buffer the associations between fear of fat and restrained eating. Specifically, negative body talk can be viewed as a social support process, allowing individuals to better regulate their body-related issues through self-disclosure and support [10, 18, 24]. From this perspective, it is possible that engagement in body talk may reduce the association between fear of fat and restrained eating. In other words, friend dyads who engage in more body talk may be less likely to engage in restrained eating, even though they may experience fears of being overweight. Supporting the view that body talk may be advantageous under certain circumstances, recent studies have demonstrated that body talk serves as a buffer against the negative impact of being overweight on body dissatisfaction and depressive symptoms [18, 24].

The current study

Summarizing the literature, it appears that body talk may be related to more body image and eating issues (e.g., Shannon and Mills [11]), but some studies have provided evidence that body talk may interact with individual characteristics (e.g., weight status) when relating to body dissatisfaction (e.g., Tan and Chow [18]). Most studies on body talk, however, have focused on the direct associations among body talk, body image, and eating behaviors. It is important to examine the complex role of body talk in the context of fear of fat and restrained eating behaviors as better understanding of this interpersonal dynamic is essential for informing interventions attempting to reduce pathological eating. Therefore, the current study examined the link between fear of fat and restrained eating and how this link might be moderated by negative body talk among female friends.

Because body talk is an inherently dyadic construct, a dyadic design was employed in which friends’ fear of fat, restrained eating, and body talk with each other were measured. The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM; Kenny et al. [28]) was employed to address the dyadic data. Broadly, this model examines an outcome variable as a function of an individual’s own characteristics (actor effect), their partner’s characteristics (partner effect), and the dyadic relationship characteristics (relationship effect). For this study, the model included fear of fat, restrained eating, and negative body talk reported by both partners (i.e., Friend A and Friend B). The actor effects represent the association between individuals’ fear of fat and their own restrained eating. In contrast, the partner effects represent the association between individuals’ fear of fat and their friends’ restrained eating. With regard to both actor and partner effects, we hypothesized that higher levels of fear of fat would be related to more restrained eating among individuals (actor effect) and their friends (partner effect). The relationship effects represent the association between negative body talk and both friends’ restrained eating. Body talk was included as a relationship-level moderator between the actor and partner effects of fear of fat on restrained eating. As noted above, negative body talk may play either an exacerbating or buffering role in the relationship between fear of fat and disordered eating, due to its co-ruminative yet relationally supportive nature [18]. Because the existing research has revealed mixed findings regarding the valence of outcomes of body talk among women, the current study took an exploratory approach to examining the moderating effects of negative body talk in relation to fear of fat and restrained eating.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The current study utilized data from a larger data set on body image and body talk in female friends (see Tan and Chow [18]). Tan and Chow [18] focused on examining the link between weight status (i.e., body mass index), depressive symptoms, and fat talk among female friends, whereas the current study focused on fear of fat and restrained eating. At a Midwestern university, 130 female psychology students were recruited and asked to bring a close same-sex friend for participation. Upon receiving informed consent from both friends, dyads completed a series of questionnaires using separate computers in different rooms. A majority of participants were Caucasian (86.5%) young adults (Mage = 19.14 years, SD = 0.96). Friendship durations varied (M = 3.47 years, SD = 4.54, range = 0 to 20), with 91% of participants ranking their participating friend as either a best friend or good friend. Participants self-reported their weight and height, which were used to calculate BMI (kg/m2). Participant BMI ranged from 16.5 to 45.6 (M = 23.61, SD = 4.50).

Measures

Fear of fat

Both friends completed the 3-item fear of fat subscale of the Antifat Attitudes Questionnaire [29]. Specifically, participants were asked the degree to which they have personal concerns about becoming fat (e.g., “I feel disgusted with myself when I gain weight.”). Participants rated the items on a scale from 1 (Very strongly disagree) to 9 (Very strongly agree). Cronbach’s α for the fear of fat subscale was 0.91.

Restrained eating

Both friends completed the restrained eating subscale (ten items) of the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire [8]. The restrained eating subscale captured participants’ tendencies and attempts to refrain from eating (e.g., “Do you try to eat less at mealtimes than you would like to eat?”). Items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Very often). Cronbach’s α for the restrained eating subscale was 0.91.

Negative body talk

To capture negative body talk, both friends were asked to complete a 3-item negative body talk scale [26]. Specifically, participants were asked to recall how often they say negative things about their own bodies with each other. Items included: (1) “How often would this [negative fat talk] occur between you and your friend?”, (2) “How often do you say negative things about your physical appearance in front of your friend?”, and (3) “How often does your friend say negative things about her physical appearance in front of you?”. Participants rated the items on a scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Very frequently). Cronbach’s α for the body talk scale was 0.85. Friends’ reports of negative body talk were significantly related, r = .37, p < 0.01. Because body talk reflects a dyadic construct, both friends’ reports were averaged to form a composite score of overall body talk in the relationship. The previous research shows this method of measuring negative body talk with a composite score to be valid [18, 24].

Data restructuring

Dyadic data can be broadly defined as distinguishable versus indistinguishable [28]. Distinguishable dyads include two members that have clear roles that differentiate themselves (e.g., parent versus child). In contrast, same-sex friends are considered indistinguishable dyads because of their symmetrical roles in the relationship. In other words, the designation of participants as “Friend A” versus “Friend B” in the data set is arbitrary. To handle indistinguishable dyadic data, the data were first restructured using the “double-entry” method [28]. Specifically, each member’s score was entered twice, once in the column for Friend A and again in the column for Friend B. An analogy of this data restructuring method would be the transformation of a wide format data to a long format data for repeated measures. In a wide format data set, responses by two friends will be in a single row, with each person’s response in a separate column. In a (restructured) long format data set, each of the two friends’ responses is in a separate column, and each dyad will have data in two rows. The Appendix provides a hypothetical example (see Campbell and Kashy [30]; Kenny et al. [28] for more details). With the restructured data, Friend A and Friend B have identical means and variances, as well as an identical covariance structure. All subsequent analyses were based on the double-entry data.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Means, standard deviations, and correlations of key variables are presented in Table 1. As expected, fear of fat was related to more negative body talk and more restrained eating, as reported by both friends. Negative body talk was also related to more restrained eating, exhibited by both friends. Higher BMI was related to more restrained eating.

Actor-partner interdependence model

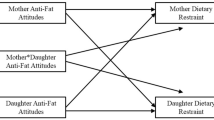

An APIM was estimated with a Multilevel Model (MLM) implemented in SPSS (Fig. 1). This model assessed relationships between individuals’ fear of fat and their own restrained eating (actor effect), individuals’ fear of fat and their friends’ restrained eating (partner effect), and negative body talk and both friends’ restrained eating (relationship effect). The overall model fit was significant, χ2(7) = 118.28, p < .001, Pseudo R2 = 0.36. Actor effects showed that individuals who had more fear of fat reported more restrained eating (b = 0.38, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001). However, partner effects showed that individuals’ fear of fat was not significantly related to friends’ restrained eating (b = − 0.05, SE = 0.04, p = .19). Negative body talk was significantly related to more restrained eating, as reported by both friends (b = 0.09, SE = 0.04, p = .04).

Actor-Partner Interdependence Model depicting actor and partner effects of fear of fat on restrained eating between female friends. Double-headed arrows represent the covariance between friends. Body talk is conceptualized as a dyadic construct that moderates the actor and partner effects. Although not shown in the figure, BMI of both friends were included as control variables. Unstandardized beta coefficients along with standard errors (in parentheses) are presented. *p < 0.05

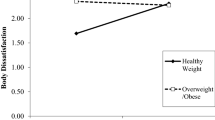

The interaction between negative body talk and individuals’ own fear of fat on restrained eating was found significant (b = − 0.11, SE = 0.04, p = 0.02). Simple slopes analyses were conducted to examine the effect of negative body talk on restrained eating at high (1 SD above mean) and low (1 SD below mean) levels of individuals’ fear of fat [31]. The simple slopes are plotted in Fig. 2. Specifically, results showed that individuals who had more fear of fat showed more restrained eating, regardless of their levels of negative body talk (b = − 0.15, SE = 0.06, p = 0.80). In contrast, although individuals with less fear of fat reported less restrained eating, engagement in more body talk increased these individuals’ reported engagement in restrained eating (b = 0.20, SE = 0.06, p = 0.002). The interaction between negative body talk and friends’ fear of fat was not significant in predicting restrained eating (b = − 0.04, SE = 0.04, p = 0.23). In other words, the relationship between negative body talk and restrained eating did not significantly differ based on friends’ fear of fat.

Discussion

The current study examined the relationship between fear of fat and restrained eating among female friends and the extent to which this relationship is moderated by negative body talk between friends. The previous literature has shed light on the direct relationships between body talk, fear of fat, and restrained eating in women. However, this study contributes to our understanding of the moderating role of body-related communication among female friends in relation to fear of fat and restrained eating behaviors, specifically for individuals with less fear of fat. In addition, this study conceptualized body talk as an interactive process between two female friends to account for the dyadic nature of the construct using a moderated APIM. This technique allowed for the simultaneous inclusion, and control, of both partners’ fear of fat and restrained eating behaviors in the dyadic model. Findings from the study shed light on the importance of body talk in relation to restrained eating among female friends which may provide avenues for interventions aimed at reducing restrained eating and body image issues among young adult women.

As predicted, actor effects revealed that individuals’ fear of fat was related to more restrained eating. These findings are consistent with an abundance of research noting the pervasive effects of fear of fat on disordered eating cognitions and behaviors [12]. Interestingly, the current study did not find a significant relationship between individuals’ fear of fat and their friends’ restrained eating. The measure of fear of fat used in the current study focused on inwardly directed fears of becoming overweight rather than general concerns with overweight. It is possible that this inward focus may explain why fears about personal weight gain are not related to friends’ restrained eating when friends’ own fears of gaining weight are controlled for in the model. However, a more broadly defined measure of antifat attitudes might reveal an association with friends’ restrained eating behaviors and should be considered in future research.

Although some previous research provides support for the positive role of body talk in buffering against negative weight-related outcomes [18, 24], findings from the current study do not corroborate this perspective. Rather, these results substantiate research indicating the negative role of body talk in relation to restrained eating [21, 22]. Specifically, negative body talk was related to more restrained eating and fear of fat, as reported by both friends. These findings are consistent with a recent meta-analysis, showing that fat talk is related to body dissatisfaction cross-sectionally and longitudinally among adult women [32].

With regard to moderation, body talk was found to exacerbate the detrimental relationship between fear of fat and restrained eating for individuals with less fear of fat. In other words, although these individuals engaged in less restrained eating than individuals with more fear of fat, negative body talk appeared to increase their levels of restrained eating, despite their low concern with weight status.

It is possible that the buffering versus exacerbatory effects of body talk may vary depending upon the type of outcome variable being captured. For instance, Tan and Chow [18] showed that the detrimental role of women’s BMI on depressive symptoms was buffered by more negative body talk, but this analysis showed that the role of women’s fear of fat on restrained eating was exacerbated by more negative body talk. One possible explanation is that the primary motive for women to engage in body talk might be to reduce their anxiety associated with body image concerns and to fulfill their desire for social support [11]. Mutual sharing of body concerns, therefore, may provide a supportive means for relieving individuals’ anxiety and negative affect stemming from body dissatisfaction. Although the social support function of body talk may reduce dyads’ negative affect and depressive symptoms, body-focused conversations appear to increase dyads’ pathological eating behaviors as demonstrated in the current study.

It is possible that body talk augments women’s pathological eating attitudes as well as their awareness of self-perceived physical imperfections, including a personally dissatisfying weight. Even if negative body talk is only directed inwardly, an individual may become cognizant that they share some of the same physical characteristics with which a friend expresses dissatisfaction. Negative weight-related talk may also increase dissatisfaction with weight due to co-rumination about negative physical characteristics, leading to more restrained eating for individuals [26]. During a weight-related co-rumination interaction, friends may commiserate about their body dissatisfaction, which may often include related negative personal experiences (e.g., peer rejection and poor esteem) due to appearance and failed weight-loss attempts. Therefore, body talk may further reinforce the importance of staying thin and fit (through restrained eating), even though these individuals have less fear of fat to begin with. It is important to note that body talk was not related to more restrained eating for individuals with more fear of fat. These individuals engaged in restrained eating regardless of their negative body talk with friends, suggesting that the pathway to restrained eating for individuals with high fear of fat is different from that of individuals with low fear of fat. Future research should examine other possible factors that may explain the link between fear of fat and restrained eating among individuals with a high level of weight concern.

Limitations and future directions

Although the current study employed a dyadic design to examine the relationships between fear of fat, body talk, and restrained eating, the cross-sectional nature of the study prevents causal interpretations of the findings. For instance, although restrained eating was defined as an endogenous variable in the APIM, it is possible that restrained eating may lead to increased body talk via a preoccupation with food [33]. If individuals experience preoccupation with food due to hunger or restraint, they may attribute these thoughts to being overweight or to not being in control of their appetite, leading to more negative talk about weight and dieting behaviors. Future research should consider utilizing longitudinal methods for examining these relationships among friends to further our understanding of the importance of fear of fat and body talk in relation to friends’ eating outcomes. There were also noteworthy limitations in the study’s use of self-reports. For instance, the use of self-reported BMI could potentially be biased by other measured variables (e.g., fear of fat). However, prior work does indicate that health risk estimates associated with variations in weight status are similar for self-reported and directly measured weight status [34]. In addition, the actor effect between fear of fat and restrained eating might be underlined by self-report biases. Future studies should attempt to assess height and weight, as well as body image variables, using objective or cross-informant measures. Finally, the current study only assessed negative body talk among dyads and did not address the role of positive body talk in weight-related cognitions and behaviors. The previous research has demonstrated that positive and negative body talk may relate to pathological eating behaviors differently [35]. Thus, future studies should attempt to address the roles of both negative and positive body talk in relation to constructs such as fear of fat and restrained eating.

Clinical implications

It is important to note that findings from this study have practical implications. These findings provide avenues for possible intervention strategies to improve body image, fear of fat, and eating behaviors in adolescent and young adult women. First, intervention attempts should consider customized help for individuals with differing levels of fear of fat. For women with less fear of fat, interventionists could provide examples and techniques for speaking positively about body image or for re-focusing body talk into more constructive communication (e.g., focusing on overall health, eating nutritiously, or engaging in beneficial physical activity). Indeed, research indicates that positive and self-accepting body talk among young women is related to more body satisfaction and self-esteem, as well as higher friendship quality [26]. For individuals with more fear of fat, interventions to reduce restrained eating may choose to focus their efforts on improving body image and reducing fear of fat, as these may be a primary mechanism underlying negative body talk with friends as well as restrained eating. It may be useful to provide these individuals with strategies for focusing on physical characteristics that elicit positive emotions or positive internal characteristics not related to weight or appearance. It may also be beneficial to teach these individuals about the long-term negative effects of restrained eating on weight and health outcomes.

Conclusion

This study utilized a dyadic approach to examine the interactive role of body talk among female friends in relation to fear of fat and restrained eating. The findings revealed that individuals’ fear of fat was related to their own increased levels of restrained eating and that body talk among female friends was related to increased levels of restrained eating, especially for individuals with less fear of fat. It is our hope that these findings will provide insight for future interventions aimed at reducing fear of fat and unhealthy eating behaviors, such as restrained eating, as well as improving body image and healthy eating behaviors among adolescent and young adult women.

References

Fredrickson BL, Roberts TA (1997) Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychol Women Q 21(2):173–206. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

Smolak L (2004) Body image in children and adolescents: where do we go from here? Body Image 1(1):15–28. doi:10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00008-1

Wiseman CV, Gray JJ, Mosimann JE, Ahrens AH (1992) Cultural expectations of thinness in women: an update. Int J Eat Disord 11(1):85–89. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199201)11:1<85::AID-EAT2260110112>3.0.CO;2-T

Levitt DH (2003) Drive for thinness and fear of fat: separate yet related constructs? Eat Disord 11(3):221–234. doi:10.1080/10640260390218729

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th edn). American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC

Levitt DH (2004) Drive for thinness and fear of fat among college women: Implications for practice and assessment. J Coll Counsel 7(2):109–118. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1882.2004.tb00242.x

Shapiro S, Newcomb M, Loeb T (1997) Fear of fat, disregulated-restrained eating, and body-esteem: prevalence and gender differences among eight-to ten-year-old children. J Clin Child Psychol 26(4):358–365. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2604_4

van Strien T, Frijters JE, Bergers G, Defares PB (1986) The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. Int J Eat Disord 5(2):295–315. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(198602)5:2<295::AID-EAT2260050209>3.0.CO;2-T

Webb HJ, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ (2014) The role of friends and peers in adolescent body dissatisfaction: a review and critique of 15 years of research. J Res Adolesc 24(4):564–590. doi:10.1111/jora.12084

Nichter M (2000) Fat talk: what girls and their parents say about dieting. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Shannon A, Mills JS (2015) Correlates, causes, and consequences of fat talk: a review. Body Image 15:158–172. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.09.003

Dalley SE, Buunk AP (2009) “Thinspiration” vs. “fear of fat”. Using prototypes to predict frequent weight-loss dieting in females. Appetite 52(1):217–221. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2008.09.019

Shaw H, Ramirez L, Trost A, Randall P, Stice E (2004) Body image and eating disturbances across ethnic groups: more similarities than differences. Psychol Addict Behav 18(1):12–18. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.12

Davison KK, Markey CN, Birch LL (2003) A longitudinal examination of patterns in girls’ weight concerns and body dissatisfaction from ages 5 to 9 years. Int J Eat Disord 33(3):320–332. doi:10.1002/eat.10142

Dalley SE, Toffanin P, Pollet TV (2012) Dietary restraint in college women: fear of an imperfect fat self is stronger than hope of a perfect thin self. Body Image 9(4):441–447

Wellman JD, Araiza AM, Newell EE, McCoy SK (2017). Weight stigma facilitates unhealthy eating and weight gain via fear of fat. Adv Online Publ Stigma Health. doi:10.1037/sah0000088

Bennett NA, Spoth RL, Borgen FH (1991) Bulimic symptoms in high school females: Prevalence and relationship with multiple measures of psychological health. J Commun Psychol 19(1):13–28. doi:10.1002/1520-6629(199101)19:1<13::AID-JCOP2290190103>3.0.CO;2-Q

Tan CC, Chow CM (2014) Weight status and depression: moderating role of fat talk between female friends. J Health Psychol 19(10):1320–1328. doi:10.1177/1359105313488982

Arroyo A, Harwood J (2012) Exploring the causes and consequences of engaging in fat talk. J Appl Commun Res 40(2):167–187. doi:10.1080/00909882.2012.654500

Jones DC, Vigfusdottir TH, Lee Y (2004) Body image and the appearance culture among adolescent girls and boys: an examination of friend conversations, peer criticism, appearance magazines, and the internalization of appearance ideals. J Adolesc Res 19(3):323–339. doi:10.1177/0743558403258847

Clarke PM, Murnen SK, Smolak L (2010) Development and psychometric evaluation of a quantitative measure of “fat talk”. Body Image 7(1):1–7. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.09.006

Royal S, MacDonald DE, Dionne MM (2013) Development and validation of the fat talk questionnaire. Body Image 10(1):62–69. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.10.003

Arroyo A, Segrin C, Harwood J, Bonito JA (2016). Co-rumination of fat talk and weight control practices: an application of confirmation theory. Health Commun. doi:10.1080/10410236.2016.1140263

Chow CM, Tan CC (2016) Weight status, negative body talk, and body dissatisfaction: a dyadic analysis of male friends. J Health Psychol 21(8):1597–1606. doi:10.1177/1359105314559621

Ousley L, Cordero ED, White S (2008) Fat talk among college students: how undergraduates communicate regarding food and body weight, shape, and appearance. Eat Disord J Treat Prev 16:73–84. doi:10.1080/10640260701773546

Rudiger JA, Winstead BA (2013) Body talk and body-related co-rumination: associations with body image, eating attitudes, and psychological adjustment. Body Image 10(4):462–471. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.07.010

Corning AF, Gondoli DM (2012) Who is most likely to fat talk? A social comparison perspective. Body Image 9(4):528–531. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.05.004

Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL (2006) Dyadic data analysis. Guilford, New York

Crandall CS (1994) Prejudice against fat people: Ideology and self-interest. J Pers Soc Psychol 66(5):882–894. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.66.5.882

Campbell LJ, Kashy DA (2002) Estimating actor, partner, and interaction effects for dyadic data using PROC MIXED and HLM5: a brief guided tour. Personal Relatsh 9:327–342

Aiken LS, West SG (1991) Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Sage, Newbury Park

Sharpe H, Naumann U, Treasure J, Schmidt U (2013) Is fat talking a causal risk factor for body dissatisfaction? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord 46(7):643–652

Tapper K, Pothos EM (2010) Development and validation of a food preoccupation questionnaire. Eat Behav 11(1):45–53. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.09.003

Stommel M, Schoenborn CA (2009) Accuracy and usefulness of BMI measures based on self-reported weight and height: findings from the NHANES & NHIS 2001–2006. BMC Public Health 9(1):421. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-421

Hart E, Chow CM, Tan CC (2017). Body talk, weight status, and pathological eating behavior in romantic relationships. Adv Online Publ Appetite. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2017.06.012

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Appendix: Hypothetical dyadic “double-entry” data

Appendix: Hypothetical dyadic “double-entry” data

Person A fear of fat | Person B fear of fat | Person A restraint | Person B restraint | Body talk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Dyad 01 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3.2 |

Dyad 01 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 3.2 |

Dyad 02 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2.8 |

Dyad 02 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2.8 |

Dyad 03 | – | – | – | – | – |

Dyad 03 | – | – | – | – | – |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chow, C.M., Ruhl, H., Tan, C.C. et al. Fear of fat and restrained eating: negative body talk between female friends as a moderator. Eat Weight Disord 24, 1181–1188 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0459-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0459-9