Abstract

Objective

This manuscript explores the characteristics of individuals diagnosed with an eating disorder who dropped out of treatment, compared with those who completed it.

Method

The participants were 196 patients diagnosed with eating disorders (according to DSM-IV-TR criteria) who consecutively began treatment for the first time in an eating disorders unit. They were assessed at baseline with a set of questionnaires evaluating eating habits, temperament, and general psychopathology. During the follow-up period, patients who dropped out were re-assessed via a telephone interview.

Results

In the course of a 2-year follow-up, a total of 80 (40.8%) patients were labeled as dropouts, and 116 (59.2%) remaining subjects were considered completers. High TCI scores in the character dimensions of Disorderliness (NS4) (p < .01) and total Novelty Seeking (NST), along with low scores in Dependency (RD4), were significantly associated with dropout in the course of 2 years. Once the results were submitted to logistic regression analysis, dropout only remained associated with high scores in Disorderliness (NS4) and, inversely, with an initial Anorexia Nervosa (AN) diagnosis (p < .05). Reasons for dropout stated by the patients included logistic difficulties, subjective improvement of their condition, and lack of motivation.

Discussion

Clinicians should handle the first therapeutic intervention with particular care in order to enhance their understanding of clients and their ability to rapidly identify those who are at risk of dropping out of treatment.

Level of evidence

Level III: Cohort Study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Eating disorders (ED) are very serious mental disorders [1]. Early and effective intervention is crucial, since prognosis sharply declines the longer the illness persists [2]. Increased knowledge of factors associated with the illness’s progression, as of factors that affect treatment outcome, could help us design tools to improve intervention quality in the future [3]. One of the factors that exert a negative influence on outcome is dropout, which unfortunately occurs quite frequently. Premature termination of treatment ranges from 20.2 to 51% in inpatients to 29–73% in outpatients [4, 5]. Although the definition of dropout is still being debated, it has been shown that patients who abandon treatment are more likely to experience a poor outcome [6]. Across the entire eating disorder spectrum, however, information about such patients is still lacking.

Several recent reviews [3, 7, 8] have presented an overview of factors associated with premature termination of treatment. Factors such as the binge/purge subtype of Anorexia Nervosa, personality styles (i.e., low self-directedness, low cooperativeness or lower persistence, high novelty seeking, and a high degree of harm avoidance) and psychological traits such as impulsivity or high maturity fear, and greater comorbidity all figure in psychopathology as depressive symptoms potentially conducive to dropout [3, 9,10,11,12]. ED patients often display low levels of motivation for treatment and higher precontemplation scores, along with dropout levels that are generally quite high [13]. Other authors add eating symptoms, nutritional status and eating disorder history, demographic features, psychopathological status, life events, family environment, and type of treatment to the list of factors [7, 12].

Despite such evidence, most previous studies have methodological limitations. The majority of them limited their focus to hospital inpatients with anorexia nervosa (AN), they were conducted on small sample sizes , mainly involved adult samples and they did not replicate their findings. Neither did they provide mid- and long-term follow-up assessment of dropout progression [3, 14]. Few studies address individual or subjective factors stated by the patients themselves as a justification for abandoning treatment. The most common reasons stated by patients to explain their abandonment of treatment are: low motivation and/or dissatisfaction with treatment (or with the therapist), external difficulties, personal circumstances, and a subjective sense of improvement [15,16,17,18].

This study’s goal was to analyze the rate and factors associated with dropout in a sample of eating-disorder patients 2 years after they began treatment in their first episode. Our hypothesis was that patients who had abandoned treatment would possess more impulsive personality traits and would display a low motivation for change through treatment. Moreover, we wanted to find out what subjective reasons for dropout would be stated by the patients themselves, as well as their current outcome.

Methods

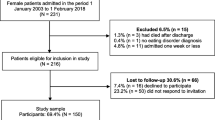

Participants

The sample consisted of one hundred ninety-six (196) individuals with a current ED diagnosis who had been referred to treatment between 2010 and 2012 at a specialized unit at Marqués de Valdecilla University Hospital (Santander, Spain). These subjects had never previously undergone treatment, and they had been free of all criterion symptoms of AN or Bulimia Nervosa (BN) according to Herzog criteria [19].

Diagnoses with DSM-IV-TR criteria [20] were carried out by a clinical specialist who applied the International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) [21]. Thirty-nine subjects met criteria for AN (thirty-one of a restrictive type and eight of a purging type), fifty-four subjects met criteria for BN (forty-two with purging and twelve with non-purging bulimia), and one hundred and three subjects met criteria for eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) (thirty-one of them with an incomplete anorexia nervosa profile, sixty-six with an incomplete bulimia nervosa profile, and six nocturnal binge-eaters).

12.6% of sample participants were males; 93% of the sample were Caucasian, 6.5% Hispanic, and .5% of Romani ethnic origin.

Procedure

A 2-year naturalistic prospective cohort follow-up study was conducted via a telephone interview specifically designed for this investigation in order to evaluate reasons for dropout and assess the “outcome”. Only those who abandoned treatment were interviewed, and the interview took place 2 years after their first contact with the hospital unit.

We defined dropout as a nonconsensual interruption of treatment ensuing from the patient’s own decision.

Patients arrived at the Eating Disorder Unit through referral from general or specialized practitioners or units. Within a week, a specialized nurse carried out initial patient evaluation: establishment of sociodemographic data, submittal of the informed consent form to the patient, administration of the aforementioned psychometric questionnaires, and routine analysis. The nurse explained how treatment would be carried out, including the prospect of both individual and family treatment. Once a patient’s individual case had been discussed by the unit team, he/she was assigned to a therapist (a clinical psychologist or a psychiatrist) within the shortest possible delay, with priority given to the most urgent cases. The therapist then carried out a diagnostic interview and provided the patient with feedback containing psychometric and analytical data. At that point it was decided whether the patient would continue treatment as an outpatient, or whether he/she would be partially or fully hospitalized.

Outpatient treatment consisted in weekly sessions of cognitive behavioral therapy according to the Fairburn model [22], coupled with family interventions (individual and group) following the Maudsley treatment model [23]. In cases where pharmacological treatment was deemed necessary, a psychiatrist was instructed to write a prescription.

All patients evaluated by our unit signed an informed consent form granting permission for their clinical history to be examined up to its present state and authorizing the gathering of psychopathological and analytical data during diagnosis and treatment. The informed consent form was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee. For purposes of analysis, we collected data from the patients’ clinical history indicating the number of medical consultation sessions they had attended, along with possible subsequent developments such as dropout, discharge or change of residence.

Measures

An experienced clinical specialist interviewed the patients at baseline; a battery of self-reported questionnaires concerning general psychopathology as well as eating disorders was subsequently administered. For all scales we herein provide the corresponding psychometric validation data for the Spanish population, as well as the bibliographical reference.

Psychiatric diagnoses

In order to assess psychiatric disorders, we applied the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). MINI has proven to have adequate reliability and validity as a diagnostic instrument for assessing mental disorders. Kappa values indicated moderate to substantial agreement, and “observed agreement” was above 88% [21].

State-trait anxiety inventory (STAI)

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) is a self-administered 20-item scale designed to assess anxiety as a state (ST-STAI) and as a trait (TR-STAI). Samples from the general population in Spain have yielded results with internal consistency ranging from .84 to .93, in terms of total points as well as in each of the subscales [24].

Beck depression inventory (BDI-II)

This scale is a self-administered 21-item questionnaire designed to assess recent depressive symptoms in the past weeks. Internal consistency was described as lying around .9 and retest reliability ranged from .73 to .96 [25].

Rosenberg self-esteem questionnaire

This scale consists of ten items. A score of less than 25 points indicates significant problems with self-esteem. The Cronbach alpha coefficient yielded a score of .87. Reliability ranged from (r = .72) to (r = .74) [26].

Attitudes towards change in eating disorders (ACTA)

This questionnaire assesses attitudes towards change in three areas—cognitive, behavioral, and affective—in ED patients. The final version consists of 59 items divided into six subscales that correspond with Prochaska and DiClemente’s stages of change: Pre-Contemplation, Contemplation, Decision, Action, Maintenance and Relapse This instrument provenly possesses high reliability, with alpha coefficients for each of the six modified subscales ranging from .74 to .90 [27].

Temperament and character inventory (TCI-R)

The TCI-R is a self-report instrument designed to assess seven independent temperament and character traits along with 25 secondary traits. Four of the seven character traits are associated with temperament. The first, Novelty Seeking (NS), is subdivided into four subscales: Exploratory excitability (NS1), Impulsiveness (NS2), Extravagance (NS3), and Disorderliness (NS4). The second character trait, Harm avoidance [HA], is subdivided into Anticipatory worry (HA1), Fear of uncertainty (HA2), Shyness (HA3), and Fatigability (HA4). The third, Reward Dependence [RD] has four subscales: Sentimentality (RD1), Openness to warm communication (RD2), Attachment (RD3) and Dependence (RD4). The fourth, Persistence (P), features Eagerness of effort (PS1), Work hardened (PS2), Ambitious (PS3), and Perfectionist (PS4).

The other three dimensions of TCI-R are designed to test character. The first, Self-directedness (SD), contains five subscales: Responsibility (SD1), Purposeful (SD2), Resourcefulness (SD3), Self-acceptance (SD4) and Enlightened second nature (SD5). The second character trait, Cooperativeness (CT), likewise contains five subscales: Social acceptance (C1), Empathy (C2), Helpfulness (C3), Compassion (C4), and Pure-hearted conscience (C5). Finally, the third, Self-transcendence (ST), has three subscales: Self-forgetful (ST1), Transpersonal identification (ST2), and Spiritual acceptance (ST3). These dimensions are considered as personality traits acquired through experience. The TCI-R inventory displays good internal consistency (range .76– .89) [28].

Eating disorders inventory (EDI-2)

In order to measure specific aspects of ED psychopathology in patients, we applied the Eating Disorders Inventory (EDI-2). With a total score cut-off value of 80, this test’s sensitivity is 91%, and its specificity is 80%. With a cut-off value set at 105 points, sensitivity is 82% and specificity is 89% [29].

Measurements at follow up

In order to gather data concerning patients’ dropout motives and their degree of satisfaction with treatment, the Eating Disorder Unit Coordinator devised a semi-structured telephone interview specifically for this project. In a series of open questions, the patients were asked to state possible reasons for having abandoned treatment, and they were asked to describe and assess their current state. The telephone interview was conducted by a person who had no relation with the Eating Disorder Unit. The Clinical Global Impression Improvement Scale (CGI-I) was used to evaluate the patient’s current state [30].

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were applied with the purpose of comparing demographic, clinical, psychopathological, and personality dimensions as well as change-attitude variables between dropouts and completers. We explored assumptions of normal distribution by applying the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and by visual inspection of the histograms. Wherever appropriate, we applied the Mann–Whitney U test, the Student T test, and χ2 tests. Cohen’s d as a measure of effect size was calculated in order to provide information about the magnitude of differences. We also carried out a binary logistic regression analysis to explore the effect of certain variables (statistically significant univariate analyses) on dropout. All tests were two-tailed, and the level of statistical significance was set at .05. In the case of qualitative results we only display descriptive percentages.

We used the SPSS Statistics 15.0 software [31].

Results

2 years after the patients had been initially evaluated, a total of 80 (40.8%) subjects were designated as dropouts, and 116 (59.2%) were considered as completers.

In terms of the type of ED diagnostic, nine patients diagnosed with AN (23.1% of all AN diagnoses) abandoned treatment, compared with 19 patients diagnosed with BN (35.2% of all BN diagnoses) and 52 subjects diagnosed with EDNOS (50.5% of all EDNOS diagnosis) (Chi-square = 9.67, gl 2, p = .008).

Regarding the timepoint at which dropout took place, nine patients (11.25% of all dropouts) abandoned treatment immediately after initial evaluation; thirty-one patients (38.75%), dropped out in the course of the first four clinical sessions, and forty subjects thereafter (with an average of 9.33 sessions attended). Thus, one can conclude that 50% of all dropouts occurred prematurely, i.e. before treatment could truly begin. Between those who abandoned prematurely and those who abandoned at a later point in time, we found no statistically significant differences on any of the scales or measures we administered.

Within that 2-year period, eight subjects (e.g. 4% of all subjects) had been admitted to hospital as inpatients, and 24 (12.1%) had been partially hospitalized. Only one of the dropout patients had been hospitalized.

Characteristics of the sample at admission

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

The average illness time span prior to referral to treatment was 65.11 months (SD 82.20 months; range 2–480). The mean age was 27.95 (SD = 10.67), with a range of 13–56 years; the mean body mass index (BMI) was 26.52 (SD = 9.49) with a range of 12.4–55.6. The mean age of eating disorder onset was 22.03 years old (SD = 9.10; range 10–52).

Regarding different diagnostic traits, those patients who were suffering from anorexia nervosa had not undergone treatment for an average period of 48.5 months (SD = 102.5). The mean age was 26.3 (SD = 11.06) and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 17.01 (SD = 1.74). Patients with bulimia nervosa had not undergone treatment for an average period of 68.7 months (SD = 67.37), whereby the mean age was 26.7 (SD = 8.8) and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 28.52 (SD = 8.54). Finally, patients with non-specified eating disorders had not undergone treatment for an average of 69.58 months (SD = 80.3), whereby the mean age was 29.25 (SD = 11.31) and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 29 (SD = 9.4).

We only found significant differences between dropouts and non-dropouts in two factors: completers attended a higher mean number of sessions, and dropouts had a significantly higher BMI at diagnosis than completers.

No differences were found with respect to the age of ED onset, nor regarding how much time had been spent away from treatment. Neither were any detectable differences associated with the level of motivation for change or psychiatric comorbidity.

We found further differences in the score points attained on certain TCI-R scales as displayed in Table 2. Patients who abandoned treatment displayed higher score points in the subscales of “Novelty Seeking” (p = .03) and “Disorderliness vs. strict rules”, (p = .007). Their score on the “Dependence” subscale was likewise significantly lower (p = .04) than that obtained by patients who remained in treatment. The effect sizes are likewise displayed in Table 2.

Results from follow-up and reasons for dropout

After a period of 2 years, we were able to locate 58 of the 80 patients who had dropped out (thus 72.5% of them). No significant sociodemographic or psychopathological differences were found between those whom we were able to recontact and those whom we could no longer locate. Neither did we find any significant differences related to the time point at which dropout took place.

We applied logistic regression in order to analyze factors associated with the probability of dropout within a period of 2 years. The variables which had been statistically significant in the previous univariate analyses were included as independent factors (subscales of TCI-R, subtypes of eating disorder diagnosis and BMI). The only factors found to be significant were “Disorderliness vs. strict rules” (NS4) (Exp B: 1.07; IC 95% 1.01–1.14; p < .01 with 67.1% of cases correctly classified) and the ED diagnosis type (AN) (Exp B: .343; IC 95%: .129–.908; p < .05 with 63.9% of cases correctly classified) .

Among the reasons cited for dropout, 20.6% (12 subjects) referred to problems due to change of residence, 18.9% (11 subjects) affirmed that they had dropped out because their condition had improved, 18.9% (11 subjects) cited lack of motivation, 15.5% (9 subjects) cited diverse motives such as pregnancy or work-related issues, 13.7% (8 subjects) stated that they had dropped out due to lack of improvement, 6% (4 subjects) cited dissatisfaction with the quality of service, and 5% (3 subjects) indicated that they had received a differing diagnosis elsewhere.

Among the patients we contacted, 34 subjects (58.6%) stated that they were doing well, 10 (17.2%) said they were doing worse, and 14 (24.1%) regarded their situation as equal.

The mean dropout CGI scores were 2.75 (SD = 1.4) and 2.5 (SD = 1.2) for completers.

Discussion

This study’s main objective was to study the dropout rate of patients 2 years after their first contact with the ED treatment unit. Previous studies in this area had found rates of abandonment ranging from 30 to 70% in outpatient settings [7]. Our results lie within those ranges, with an overall dropout rate of 40.8%. The majority of cases in our sample were diagnosed with EDNOS, with a dropout rate of 50.5%, whereas AN patients displayed a dropout rate of 23.1%.

Regarding the type of ED, the literature points out that AN-P conditions correlate with a greater tendency to abandon treatment [9]. In our study, however, the majority of dropouts were in the EDNOS category (which consisted either of incomplete AN or BN conditions, or of binge-eating disorder cases). In our sample, an AN diagnosis corresponded with less probability of dropout in comparison with EDNOS patients. Notwithstanding, the total of AN patients who subsequently abandoned treatment is very high: 23.1%. Thus, one cannot conclude that an AN diagnosis could have “shielded” such patients from dropout (the sample size did not allow us to distinguish between purgative and restrictive cases of AN).

We found no significant differences regarding the moment in time at which dropout took place. As several authors have pointed out, it seems as if the effect of therapy—for better or for worse—emerges relatively early in the process of treatment [9, 12, 32]. Half of the patients in our sample dropped out before attending their fourth clinical session, and some dropped out without even having initiated treatment. Perhaps certain subjects who have an incomplete or less severe condition might rapidly become aware of their situation and start initiating a series of changes on their own. Our results seem to indicate that those patients who drop out tend to do so relatively early, and the most probable assumption is that such dropouts tend to be those who are in a less critical state when they are diagnosed. At the moment when our patients were evaluated, their body-mass index (BMI) was significantly higher; on the other hand, although they did have less significant scores on depressive symptom scales, they generally tended to score higher in self-esteem and lower in psychiatric comorbidity. This could also exert an influence on the manner in which the assistance team provided counsel [12].

Our second goal was to find out whether certain factors are predictors of dropout, and whether they are mainly associated with the subjects’ own personality traits, or with their level of motivation for change. Previous studies in this specific area [4, 7, 12, 13], have pointed out that factors associated with the personality traits of low cooperativeness, low self-directedness, high novelty seeking, high avoidance or self-transcendence, impulsivity, and fear of maturity all correlate significantly with dropout. In our sample, however, a greater tendency toward dropout was associated with two temperament profile scores: a high rate in “Novelty Seeking”, and a low rate in “Reward Dependence”. The first of these traits (NS) is associated with impulsive decision-making, with a tendency to avoid frustration, and with the avoidance of norms and rules. On the other hand, low scores in “Reward Dependence” are related with indifference, independence and insensitivity to social pressures—traits which, on the whole, could indicate that the patient has difficulty in becoming involved in treatments that demand a certain amount of commitment to others, along with the requirement of following norms such as attending appointments and fulfilling certain tasks.

Even though our initial hypothesis was that dropout would correlate significantly with motivation for change, this was not confirmed by the response obtained in the questionnaire of attitudes towards change applied at the beginning of treatment. In the telephone interview conducted during follow-up, the patients who left said that having a low motivation was one of the reasons for dropping out.

Finally, our study included a second phase devoted to quality feedback. Patients who had abandoned treatment were asked to state, in their own words, how they perceived their current condition and what reasons had led them to drop out. Until now, few studies have looked into reasons for dropout stated by the patients themselves [16,17,18]. Our patients mentioned certain logistic factors such as change of residence, or major life events (shifting circumstances at the workplace, or pregnancy). On the whole, these made up 41.1% of the stated reasons for dropout. Other patients stated lack of motivation, lack of improvement or dissatisfaction with treatment (the latter making up almost 39% of all reasons stated). Certain authors recommend that patients should be allowed a greater involvement in the decision-making process in order to reduce the number of dropouts: this proposition is relevant with regard to our sample, in which 50% of patients abandoned treatment prematurely [8, 15]. Along these lines, other authors point out the importance of self-determination and its relation with motivation for change. It would also be recommendable to start to incorporate and apply specific therapeutic strategies such as Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET) on a more regular basis [15]. Moreover, certain authors suggest that reasons stated for dropout such as logistics (change of location, etc.) on the one hand, and subjective improvement on the other, should be viewed and classified as separate types of dropout altogether [8, 18].

Previous research points out a high correlation of dropout with a more negative prognosis [2]. In our case, over half of the dropouts (58.6%) affirmed that they were doing well, and only 17.2% viewed their condition as having deteriorated. Although our study has evident limitations (the patients were interviewed only by telephone, and some of them may not have wished to be identified in order to avoid pursuing further treatment or they might have pursued other treatments on a private basis and did not communicate this fact in the course of the follow-up interview), it would confirm the results obtained by certain authors, suggesting the possibility that dropout is not necessarily associated with a worsening of the illness [16, 17]. Furthermore, among the reasons stated by subjects to justify their dropout decision, almost 50% indicate improvement, or the emergence of environmental factors conducive to change and to a greater awareness of the harm caused by the disorder. Nevertheless, the relatively small sample size in this study and the qualitative character of our analysis suggest that we must handle these results with precaution. We are also aware that the inclusion of other variables in the binary logistic regression analysis could perhaps have led to the emergence of other significant variables in the predictive model. However, we have opted for a more conservative approach, by including only those variables that resulted as being statistically significant in the univariate analysis. It would be necessary to conduct further follow-up studies in order to evaluate patients’ progression more precisely and objectively, while drawing on a wider sample. Since we do not know which subjective reasons encouraged patients to remain in treatment, and since we cannot compare reasons for remaining with reasons for abandoning treatment, the validity of these findings is somewhat undermined. This also prevents us from drawing a satisfactory number of conclusions with practical clinical implications.

We would like to point out further limitations. First of all, we were not able to evaluate the treatment the patients underwent: although protocolled, it was administered by several different therapists. Furthermore, we lack data regarding pharmacological treatment in a significant number of patient cases. The sample, although large, is quite heterogeneous. The presence of a large number of patients diagnosed as EDNOS may also make it difficult to draw general conclusions. And the overall mixture of minors with adult patients and the presence of all types of eating disorder diagnosis can indeed affect results: reasons for dropout could be quite diverse in this thoroughly mixed population. Other researchers might not necessarily agree with our definition of dropout, which they might consider controversial [33]. Some authors may consider that those patients who failed to engage or only attend the initial evaluation session should be studied separately. So far the small sample sizes have not allowed the generalization of the findings [12].

In factors associated with dropout, we included neither the relation with the therapist, nor a series of other potentially useful sociodemographic or family-related factors. All of these could have been of particular relevance, since a majority of patients who abandoned treatment did so during the very first sessions [13, 29]. One must also take into account that some patients abandoned treatment later than others. The difference between having undergone several treatment sessions vs. hardly having undergone any treatment whatsoever could be a factor that exerts a certain influence on the patient’s subsequent progression. We should also remind the reader that the follow-up interview after 2 years was carried out via telephone, without administering questionnaires or having a face-to-face encounter: this can have a decisive effect on results. Nevertheless, other authors who applied a methodology similar to our own reached conclusions comparable with those who conducted face-to-face interviews [14, 15].

To summarize, this study examined the patient dropout rate and related factors within the framework of an eating disorder treatment program.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has investigated the dropout percentage in a sample of ED-diagnosed patients who were consistently referred to a specialized ED unit, and whose basic common characteristic was that they had never previously undergone treatment for an ED pathology; consequentially, they did not fulfill recovery criteria from ED in the past. The patients in our sample were experiencing their very first encounter with treatment without having undergone previous treatment failures, and were mostly outpatients.

Our study indicates that abandonment of clinical treatment occurs early—sometimes, in fact, immediately after initial contact with the treatment center. It likewise indicates that those patients who tend to abandon treatment are (1) those who feel less in danger, because their symptoms seem to be less severe; and/or (2) those who tend to make rash decisions and display a low tolerance for frustration or imposed norms.

Furthermore, in view of subjective reasons for dropout stated by the patients themselves, it becomes evident that the first clinical intervention and the choice of therapeutic strategy both play a crucial role in their overall prognosis. These findings stress the importance of rapidly becoming acquainted with the patients’ expectations and thereby adapting the type of treatment to each individual. This could reduce the percentage of dropouts and improve the general participation rate [34]. Thus it would be highly pertinent to conduct additional mid-term and long-term follow-up studies.

References

Steinhausen HC (2009) Outcome of eating disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 18:225–242. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2008.07.013

Currin L, Schmidt U, Treasure J, Jick H (2005) Time trends in eating disorder incidence. Br J Psychiatry 186:132–135. doi:10.1192/bjp.186.2.132

Vall E, Wade TD (2015) Predictors of treatment outcome in individuals with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord 48:946–971. doi:10.1002/eat.22411

Bandini S, Antonelli G, Moretti P, Pampanelli S, Quartesan R (2006) Factors affecting dropout in outpatient. Eat Weight Disord 11(4):179–184. doi:10.1007/BF03327569

Fassino S, Abbate-Daga G, Pier A, Leombruni P, Rovera GG (2003) Dropout from brief psychotherapy within a combination treatment in bulimia nervosa: role of personality and anger. Psychother Psychosom 72:203–210. doi:10.1159/000070784

Watson HJ, Fursland A, Byrne S (2013) Treatment engagement in eating disorders: who exits before treatment? Int J Eat Disord 46:553–559. doi:10.1002/eat.22085

Fassino S, Pierò A, Tomba E, Abbate-Daga G (2009) Factors associated with dropout from treatment for eating disorders: a comprehensive literature review. BMC Psychiatry 9:67. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-9-67

DeJong H, Broadbent H, Schmidt U (2012) A systematic review of dropout from treatment in outpatients with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 45:635–647. doi:10.1002/eat.20956

Wallier J, Vibert S, Berthoz S, Huas C, Hubert T, Godart N (2009) Dropout from inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa: critical review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord 42:636–647. doi:10.1002/eat.20609

Abbate-Daga G, Amianto F, Delsedime N, De-Bacco C, Fassino S (2013) Resistance to treatment in eating disorders: a critical challenge. BMC Psychiatry 13:294. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-13-294

Bados A, Balaguer G, Saldaña C (2007) The efficacy of cognitive–behavioral therapy and the problem of drop-out. J Clin Psychol 63:585–592. doi:10.1002/jclp.20368

Watson HJ, Levine MD, Zerwas SC, Hamer RM, Crosby RD, Sprecher CS et al (2016) Predictors of dropout in face-to-face and internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa in a randomized controlled trial. Int J Eat Disord. doi:10.1002/eat.22644

Rodríguez-Cano T, Beato-Fernandez L, Moreno LR, Vaz Leal FJ (2012) Influence of attitudes towards change and self-directness on dropout in eating disorders: a 2-year follow-up study. Eur Eat Disord Rev 20:123–128. doi:10.1002/erv.2157

Roux H, Ali A, Lambert S, Radon L, Huas C, Curt F et al (2016) Predictive factors of dropout from inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa. BMC Psychiatry 16(1):339. doi:10.1186/s12888-016-1010-7

Jordan J, McIntosh VV, Carter FA, Joyce PR, Frampton CM, Luty SE et al (2014) Clinical characteristics associated with premature termination from outpatient psychotherapy for anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev 22:278–284. doi:10.1002/erv.2296

Björk T, Björck C, Clinton D, Sohlberg S, Norring C (2009) What happened to the ones who dropped out? Outcome in eating disorder patients who complete or prematurely terminate treatment. Eur Eat Disord Rev 17:109–119. doi:10.1002/erv.911

Di Pietro G, Valoroso L, Fichele M, Bruno C, Sorge F (2002) What happens to eating disorder outpatients who withdrew from therapy? Eat Weight Disord 7:298–303. doi:10.1007/BF03324976

Ter Huurne ED, Postel MG, de Haan HA, van der Palen J, DeJong CA (2017) Treatment dropout in web-based cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders. Psychiatry Res 247:182–193. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.11.034

Herzog DB, Sacks NR, Keller MB, Lavori PW, von Ranson KBGH (1993) Patterns and predictors of recovery in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32:835–842. doi:10.1097/00004583-199307000-00020

APA (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Association, 4th edn. Masson, Barcelona

Bobes J (1998) A Spanish validation study of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview. Eur Psychiatry. 13(Suppl 4):198–199

Fairburn C (2008) Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guilford Press, London

Treasure J (2007) Skills-based learning for caring a loved one with an eating disorder: the new Maudsley Method. Routledge, London

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE, Buela-Casal G, Cubero NS, Guillén-Riquelme A (2011). STAI: Cuestionario de Ansiedad Estado-Rasgo. 8.a ed. TEA Ediciones, Madrid

Sanz J, García-Vera MP, Espinosa R, Fortún M, Vázquez C (2005) Adaptación española del Inventario para la Depresión de Beck-II (BDI-II). Propiedades psicométricas en pacientes con trastornos psicológicos [Spanish adaptation of the Beck Depression Inventory- II (BDI-II): Psychometric features in patiens with psychological disorders]. Clínica y Salud, 16, 121–142. http://www.copmadrid.org/web/articulos/2005162/clinicaysalud

Vázquez AJ, Jiménez R, Vazquez-Morejón R (2004) Escala de autoestima de Rosenberg. Fiabilidad y validez en población clínica española. Apuntes de Psicología 22:247–255

Beato Fernandez L, Rodriguez Cano T (2003) Attitudes towards change in eating disorders (ACTA). Development and psychometric properties. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría 31:111–119. doi:10.1007/BF03353420

Gutierrez F, Torrens M, Boget T, Martin-Santos R, Sangorrin J, Perez G et al (2001) Psychometric properties of the temperament and character inventory (TCI) questionnaire in a Spanish psychiatric population. Acta Psychiatr Scand 103:143–147. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00183

Corral S, González M, Pereña J, Seisdedos N (1998) Adaptación española del Inventario de trastornos de la conducta alimentaria. In: Garner D (ed) EDI-2: Inventario de Trastornos de la Conducta Alimentaria. Manual. TEA, Madrid

Guy W (1976) ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Rockville

Norusis MJ (2006) SPSS for Windows: Release 15.0. SPSS, Chicago

Sly R, Morgan J, Mountford V, Lacey J (2013) Predicting premature termination of hospitalised treatment for anorexia nervosa: the roles of therapeutic alliance, motivation, and behaviour change. Eat Behav 14(2):119–123. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.007

Ackard D, Richter S, Egan A, Cronemeyer C (2014) Poor outcome and death among youth, young adults, and midlife adults with eating disorders: an investigation of risk factors by age at assessment. Int J Eat Disord 47(7):825–835. doi:10.1002/eat.22346

Le Grange D, Loeb KL (2007) Early identification and treatment of eating disorders: prodrome to syndrome. Early Interv Psychiatry 1(1):27–39. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7893.2007.00007.x

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors declare their individual contributions to the manuscript. The authors contributed to the study as follows: Andrés Gómez del Barrio participated in all phases of the study and in writing the manuscript. Yolanda Vellisca Gonzalez, Jana González Gómez, José Ignacio Latorre Marín, Laura Carral-Fernández, Santos Orejudo Hernandez, Inés Madrazo Río-Hortega and Laura Moreno Malfaz all contributed in equal measure to designing the study, actively recruiting participants, writing the manuscript and proofreading the final versions. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The final manuscript has been approved by all authors. None of them have any conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gómez del Barrio, A., Vellisca Gonzalez, M.Y., González Gómez, J. et al. Characteristics of patients in an eating disorder sample who dropped out: 2-year follow-up. Eat Weight Disord 24, 767–775 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0416-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0416-7