Abstract

Purpose

To analyze self-esteem, as well as the different peer influence components (messages, interactions and likability) as predictors of body dissatisfaction in children with obesity.

Method

A total of 123 children aged between 10 and 12 years were divided into two groups according to their body mass index. The group with obesity was comprised of 36 boys and 21 girls and the group with normal weight of 32 boys and 34 girls. All of the participants answered the Body Shape Questionnaire—16, the Inventory of Peer Influence on Eating Concerns, and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale.

Results

The hierarchical multiple regression analysis for each group showed that likability and peer messages explain 67% of the body dissatisfaction variance in children with obesity and 54% in children with normal weight.

Conclusion

Peer influence predicted body dissatisfaction in children; however, children with obesity assimilate messages from their peers differently compared with children with normal weight.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obesity is deemed as an excessive accumulation of fat in the body which poses a health risk [1]. Currently, obesity is a health problem worldwide mainly in the United States, Mexico, and New Zealand which have the highest rates [2]. Specifically, over the last two decades, child obesity has risen 65% in developing countries and 48% in developed countries [3].

Child obesity has become a global concern due to its negative repercussions. Literature indicates that pediatric obesity does not only have consequences during childhood, but can also potentiate harmful effects in adults’ health [4]. Side effects of child obesity have been divided into two categories: medical and psychosocial problems. Some of the most common medical problems are: diabetes, high blood pressure, fatty liver disease, and obstructive sleep apnea [3]. Whereas, a negative self-image, eating disorders, and a low self-esteem are typical psychosocial issues [5]. In addition, it has been reported that people with overweight or obesity are less satisfied with their bodies [6] and have a lower self-esteem [7, 8] than individuals with normal weight.

Despite the fact that several factors lead to body dissatisfaction, the social context plays an important role in people’s acceptance or rejection of their body image [9]. This article will focus on peer influence, considering that peers and friends have a significant influence on children’s behavior, attitudes, and knowledge while providing information on the world, themselves, giving emotional support, trying and adopting values irrespective of their parents, and offering a sense of belonging [10]. Thus, peer messages are expected to be more clearly understood and internalized by preadolescents [11] when they concern their own body image.

Relationships between body dissatisfaction and peer influence have been found in children [12], as well as their relation with self-esteem [13]. Furthermore, it has been established a predictive effect of body mass index (BMI), peer influence, and self-esteem on body dissatisfaction [14]. However, most of the participants in these studies were children with normal weight (75–85%).

On another hand, peer influence has been studied as a global construct [15]. Nevertheless, studies such as Shroff and Thompson [16] and Matera, Nerini, and Stefanile [17] deemed evaluating specific dimensions of peer influence more relevant considering that it is a critical factor in self-assessment of appearance. In the latter, studies were considered samples of adolescents aged between 14 and 19 years. In both cases, different dimensions of peer influence were evaluated, e.g., appearance conversations with friends, teasing, peer attributions relate to appearance, and perceived friend preoccupation with weight, dieting, and opinions about a perfect body. The main findings were that adolescents take their peers’ opinion into account to judge their own appearance [16]; teasing from peers affects their body image; appearance conversations with friends; and peer attributions related to appearance predict body dissatisfaction [17]. A third study with the same aim was the one of Thompson et al. [18], which differs from the last two studies due to the fact that it was conducted with a sample of adolescents with different BMI. The authors report different effects of peer influence among participants with normal weight and overweight, and similarly, the prediction of body dissatisfaction from peer influence is different according to the BMI.

After reviewing these studies, the following conclusions were reached: (1) peer influence plays an important role in acceptance of body image considering that a person’s body perception is affected by his/her social circle’s attitudes and beliefs; (2) low self-esteem is associated with obesity; (3) The BMI is decisive in the development of body dissatisfaction, despite the fact that most of the body image studies have been carried out with samples of more than 75% normal weight children, and consequently, it is not possible to generalize findings to children with obesity; (4) most studies conducted with children agree on the need to continue studying this population, especially children with obesity, with the purpose of understanding the problem better and hence, improve the prevention and treatment programs focused on body dissatisfaction in children, since this last variable could be the beginning of an abnormal eating behavior during childhood or adulthood, as well as the development of eating disorders in extreme cases. Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze self-esteem and the different peer influence components (messages, interactions, and likability) as body dissatisfaction predictors in children with obesity.

Materials and method

Participants

One hundred and twenty-three preadolescents selected from a sample of 1023 students that took part in a study aimed at examining satisfaction with body image. To select the sample for this study, two inclusion criteria were established: (1) boys or girls with obesity, this means, a BMI equal to or greater than the 97th percentile [19] and (2) participants aged between 10 and 12 years. Under these criteria, 36 boys and 21 girls (M = 11.00, SD = 0.78 years) were selected. A second group with 32 boys and 34 girls with a BMI between the 3rd and 85th percentile [19] (M = 11.36, SD = 0.79 years), this means normal weight, was set up as a comparison group. All of the participants attended public primary schools and lived in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area, specifically in the municipality of Tlalnepantla de Baz, which is considered an urban area. The human development index in this municipality is 0.8426 and its per capita income is 14.702 dollars a year [20]. Demographic information obtained by school authorities indicates that the participants came from a lower–middle socioeconomic level.

Questionnaires and variables

Body dissatisfaction The Body Shape Questionnaire—16 (BSQ-16) [21] designed to evaluate body image satisfaction through 16 items. This is a self-reporting questionnaire with six Likert response options ranging from never to always. In the literature review carried out for this study, Evans and Dolan [21] found an excellent Cronbach’s alpha (0.96) among the British population, aside from the fact that no study evaluating psychometric properties of the BSQ-16 was found in Mexican population, due to which some of them were calculated during Phase 1 of this study. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93 was obtained in this study both for the group with obesity and with normal weight.

Messages, interaction and peer likability The Inventory of Peer Influence on Eating Concern (I-PIEC) [22] estimates peer influence on children’s eating and body concerns. This questionnaire consists of 30 items with five Likert response options ranging from never to always. Oliver and Thelen [22] report five factors for this instrument: messages (α = 0.92), interaction with boys (α = 0.76), interaction with girls (α = 0.80), likability with boys (α = 0.88), and likability with girls (α = 0.88). On the other hand, Amaya, Mancilla, Alvarez, Ortega, and Bautista [23] adapted and evaluated the psychometric properties of the I-PIEC in Mexican population aged between 10 and 19 years. Amaya et al. created two versions: a version for girls with 22 items (α = 0.94) and a version for boys with 20 items (α = 0.92). Three factors resulted from both versions: (1) messages which refer to how often boys and girls receive negative messages about their bodies or eating habits (e.g., “boys tease me or make fun of me about the size or shape of my body”); (2) likability with the opposite sex which evaluates the extent to which children believe that being thin will increase their likability with the opposite sex (e.g., “I think that girls/boys would talk to me more if I were thinner”), and (3) interactions with the same sex which evaluates how often boys and girls interact (talk, compare, and exercise) regarding topics such as eating and body issues (e.g., “Girls/boys and I compare how our bodies look in our clothes”). The differences between the versions proposed by Amaya et al. are two: (1) the version for girls has 22 items and the version for boys has 20 items, and (2) both versions have the same 20 items, the difference between them is the way they are written according to the participant’s sex [e.g., “I think that boys think I would look better thinner” (version for girls), “I think that girls think I would look better thinner” (version for boys)].

For this study, only the 20 items in the Mexican versions of the I-PIEC were used, in such a manner that peer messages were evaluated with 12 items, likability with the opposite sex with five items and interaction with peers with three items. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.94 and 0.78 for messages, 0.78 and 0.78 for likability, and 0.68 and 0.55 for interactions for the groups with obesity and normal weight, respectively.

Self-esteem The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) [24] measures the beliefs and attitudes a person has about himself/herself. This self-reporting questionnaire consists of ten items with four Likert response options ranging from I totally agree to I totally disagree. The psychometric properties in adolescents between 13 and 15 years of age were evaluated in Mexican population. The authors reported an appropriate internal consistency and a two-factor structure: positive self-esteem and lack of self-esteem [25]. In the sample of the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.75 for the group with obesity and 0.82 for the normal weight group.

Procedure

The research protocol was submitted to the primary school authorities, and once it was approved, informed consent from parents and participants was obtained. This study was divided into two phases: (1) Questionnaire standardization: the psychometric properties of the BSQ-16 and RSES were calculated with a sample independent of this study’s sample, composed of boys and girls from public primary schools, (2) Main research: participants were asked to answer the questionnaires in their classroom. Two eating disorder and body image experts were in charge of administering the questionnaire. One of them explained the purpose of the study and both clarified participants’ doubts.

Statistical analysis

An exploratory factorial analysis (EFA) was conducted using SPSS for Windows version 20 and a confirmatory factorial analysis (CFA) through the Structural Equations Program (EQS for Windows, version 6.1). For the latter analysis, the following indexes were taken into consideration: X2/gl, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and comparative fit index (CFI).

In addition, the following tests were performed using the SPSS-20: (1) Student t test for independent groups with the purpose of estimating the differences in body dissatisfaction, self-esteem, and peer influence components (messages, interactions, and likability) between the groups with obesity and normal weight; (2) Pearson correlations to analyze the association between the study variables in both groups, and (3) hierarchical multiple regression analysis to know if self-esteem and peer influence components explain body dissatisfaction in children with obesity and normal weight. Statistical significance was established based on an 0.05 alpha.

Results

Phase 1: Questionnaire standardization The data obtained from the EFA and the CFA of the BSQ-16 and the RSES are shown in Table 1 where an excellent and appropriate internal consistency of the BSQ-16 and the RSES, respectively, can be observed. The EFA resulted in a one-dimensional structure for the BSQ-16 and in a two-factor structure for the RSES. The structure of both instruments was confirmed by the CFA with good adjustment indexes.

Once the appropriate psychometric properties of all of the questionnaires were determined, the second phase of this research was performed.

Phase 2: Main research The mean and standard deviation of each group’s study variables are shown in Table 2. According to the Student t test, several significant differences in body dissatisfaction, peer messages, and likability with the opposite sex can be observed between the groups. In all of the significant variables, the obese group obtained higher scores when compared with the normal weight group. This suggests that obese children are more affected by peer messages about body image and, consequently, may feel more dissatisfied with their own body.

Significant correlations between body dissatisfaction and likability with the opposite sex were observed in both groups (group with obesity r = 0.77 and group with normal weight r = 0.66), these being the highest correlations; whereas, the lowest correlations were between self-esteem and interactions with the same sex (r = −0.28) for the group with obesity and self-esteem with body dissatisfaction (r = −0.25) for the group with normal weight (see Table 3).

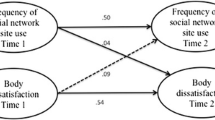

A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted to determine if the components of peer influence and self-esteem predicts body dissatisfaction in children with obesity. As shown in Table 4, peer influence components explain 67% of the variance in body dissatisfaction in children with obesity. In spite of this, only likability with the opposite sex (β = 0.49, p < 0.001) and peer messages (β = 0.41, p < 0.001) had a significant contribution. Self-esteem was included in the model in step 2, but did not have a significant contribution to the variance.

As observed in Table 4, body dissatisfaction of normal weight children was only demonstrated by peer influence components which explain 54% of the variance. In step 1, only the likability with the opposite sex (β = 0.56, p < 0.001) and the interactions with the same sex (β = 0.34, p < 0.01) had a significant contribution. In step 2, self-esteem was included in the model, but did not have a significant contribution to the variance.

In summary, 67% of body dissatisfaction variance in children with obesity and 54% of the body dissatisfaction variance in normal weight children were explained with this model.

Discussion

The purpose of this study’s Phase 1 was the estimation of the psychometric properties of the BSQ-16 and the RSES. The BSQ-16 showed excellent reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90), consistent with the previous studies [21, 26, 27] and its one-dimensional structure reached an acceptable adjustment (CFI = 0.95 and RMSEA = 0.05), according to Schreiber, Stage, King, Nora, and Barlow [28]. Findings in this study are similar to those observed in German population (CFI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.12) [26], Euro-American (CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.09), Hispanic-American (CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.08), and Spanish (CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.07) [27]. On the other hand, the RSES showed adequate reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.73), in spite of the fact that this result is different from other Spanish versions that report a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 and 0.88 [29], but coincides with a Mexican study with adolescents where alpha values ranged from 0.68 to 0.75 [25]. Consistent with a previous study, the RSES showed a two-dimensional structure [30] with appropriate adjustment indexes (CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.07), even though these findings are lower than those found in Supple, His, Plunkett, Peterson, and Bush’s cross-cultural study [31] with samples of Euro-American (CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.11), Armenian and Iranian (CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.05), and Latin Americans (CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.04). The findings of the first phase enable compliance of any prerequisites for research, such as having the appropriate tools to evaluate variables and target population. However, to our knowledge, this is the first research that evaluates the psychometric properties of the BSQ and the RSES in preadolescents. Considering that some authors have suggested the presence of body dissatisfaction [32] and low self-esteem [7, 8] in this population, it is recommended that future research confirms and extends these findings.

The general aim of this study was to analyze the predictor variables of body dissatisfaction in children with obesity. First of all, the group with obesity obtained the highest body dissatisfaction scores and was psychologically more vulnerable to peer messages and to being less likable with peers of the opposite sex than the normal weight group. These results are consistent with those of the previous research [33]. This data support the theory that children with obesity may be subject to a greater pressure to lose weight, due to the fact that body image is one of the main characteristics that is considered when friends are chosen since early childhood [11].

As far as self-esteem is concerned, both groups (with obesity and normal weight) showed high scores without any statistical differences, in contrast to the previous research [7, 8]. Some studies [34, 35] suggest that support and positive interactions with family during preadolescence can help build a high self-esteem. This idea may explain why the children of this study got a high score in self-esteem, considering the possibility that children from this municipality live in a social environment in which they are accepted and valued by others, thus allowing them to appreciate and accept themselves.

On the other hand, body dissatisfaction in the group with obesity was predicted by variables such as likability and peer messages, whereas in the normal weight group, it was explained by likability and interactions with peers. In both groups, a low level of peer likability was the best body dissatisfaction predictor, reinforcing the belief that being thin could increase their likability with peers [22]. Consequently, the results of this study point out that body satisfaction or dissatisfaction is linked to social acceptance at younger ages, regardless of the BMI.

In addition, but only for the group with obesity, the peer message variable which evaluates how often a person receives negative messages or is made fun of his/her eating habits and body image was a predictor of body dissatisfaction. This finding can be explained by the fact that peers share their expectations, exchange ideas on what is appropriate, normal or beautiful, and express their desires regarding body appearance [11] in their conversations, thus creating rules to be followed within the group. Based on this, when one of the members of the group does not meet the socially established “ideal” body standard, he/she may become a victim of bullying [36] and be at risk of suffering body dissatisfaction [17].

The main contribution of this study is to provide evidence of peer influence on the body image of children with a different BMI, finding that peers promote body image awareness, and, therefore, the acceptance or rejection of their own bodies. The kind of influence is not the same for all children, considering that peer influence is assimilated differently by children with obesity than by children with normal weight. It is known that interventions within social groups are more promising than those addressed to an individual outside his/her context. Due to this, intervention programs focused on body image with the peer influence component and considering individual differences are suggested.

Some of the limitations of this article are first of all, the lack of an analysis by sex according each BMI group, since, in literature, there are discrepancies on the role of the peer influence by sex [37, 38]. A second limitation is the lack of an evaluation of the consequences of obesity in children’s health which must be taken into account in future research to propose and design preventive programs that promote body image acceptance, and at the same time, encourage a healthy diet to prevent psychological and medical conditions in adulthood.

Likewise, in future research, parental influence must be considered, since especially in Mexico, parents deem child obesity as a health indicator and it is a well known fact that a “chubby” child is not necessarily well fed [39].

References

World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets. Accessed Sept 2008

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Obesity Update. http://www.oecd.org/health/fitnotfat. Accessed June 2014

Vadillo F, Rivera JA, González T, Garibay N, García JA (2012) Obesidad infantil. In: Rivera JA, Hernández M, Aguilar CA, Vadillo F, Murayama C (eds) Obesidad en México: Recomendaciones para una política de Estado. UNAM, Dirección General de Publicaciones y Fomento Editorial, México, pp 233–257

Reily JJ, Methven E, McDowell ZC, Hacking B, Alexander D, Stewart L et al (2003) Health consequences of obesity. Arch Dis Child 88:748–752. doi:10.1136/adc.88.9.748

Unikel C, Vázquez V, Kaufer-Horwitz M (2012) Determinaciones psicosociales del sobrepeso y la obesidad. In: Rivera JA, Hernández M, Aguilar CA, Vadillo F, Murayama C (eds) Obesidad en México: Recomendaciones para una política de Estado. UNAM, Dirección General de Publicaciones y Fomento Editorial, México, pp 189–209

Sarwer DB, Thompson JK, Cash TF (2005) Body image and obesity in adulthood. Psychiatr Clin N Am 28:69–87. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2004.09.002

Franklin J, Denyer G, Steinbeck KS, Caterson ID, Hill AJ (2006) Obesity and risk of low self-esteem: a statewide survey of Australian children. Pediatr 118(6):2481–2487. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0511

Strauss RS (2000) Childhood obesity and self-esteem. Pediatrics 105(1):15–19. http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/105/1/e15. Accessed June 2014

Rodgers RF, Paxton SJ, McLean SA (2014) A biopsychosocial model of body image concerns and disordered eating in early adolescent girls. J Youth Adolesc 43(5):814–823. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-0013-7

Kail RV, Cavanaugh JC (2006) Desarrollo humano: Una perspectiva del ciclo vital. 3a. ed. México: Cengage Learning Editores

Cunningham SA, Vaquera E, Maturo CC, Narayan KMV (2012) Is there evidence that friends influence body weight? A systematic review of empirical research. Soc Sci Med 75:1175–1183. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.024

Clark L, Tiggemann M (2007) Sociocultural influences and body image in 9 to 12 year old girls: the role of appearance schemas. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 36(1):76–86. doi:10.1080/15374410709336570

Griffiths JA, McCabe MP (2000) The influence of significant others on disordered eating and body dissatisfaction among early adolescent girls. Eur Eat Disord Rev 8:301–314. doi:10.1002/1099-0968(200008)8:4<301::AID-ERV357>3.0.CO;2-C

Donht H, Tiggeman M (2006) The contribution of peer and media influences to the development of body satisfaction and self-esteem in young girls: a prospective study. Dev Psychol 42(5):929–936. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.929

Aliyev B, Türkmen A (2014) Parent, peer and media effect on the perception of body image in preadolescent girls and boys. Univers J Psychol 2(7):224–230. doi:10.13189/ujp.2014.020703

Shroff H, Thompson JK (2006) Peer influences, body image dissatisfaction, eating dysfunction and self-esteem in adolescent girls. J Health Psychol 11(4):533–551. doi:10.1177/1359105306065015

Matera C, Nerini A, Stefanile C (2013) The role of peer influence on girls’ body dissatisfaction and dieting. Eur Rev Appl Psychol 63:67–74. doi:10.1016/j.erap.2012.08.002

Thompson JK, Shroff H, Herbozo S, Cafri G, Rodriguez J, Rodriguez M (2007) Relations among multiple peer influences, body dissatisfaction, eating disturbance, and self-esteem: A comparison of average weight, at risk of overweight, and overweight adolescent girls. J Pediatr Psychol 32(1):24–29. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsl022

World Health Organization. Growth reference data for 5–19 years. http://www.who.int/growthref/en/. Accessed Aug 2013

Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal. Sistema Nacional de Información Municipal. http://www.inafed.gob.mx. Accessed Apr 2015

Evans C, Dolan B (1993) Body Shape Questionnaire: derivation of shortened “alternate forms”. Int J Eat Disord 13:315–321. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199304)13:3<315::AID-EAT2260130310>3.0.CO;2-3

Oliver KK, Thelen HM (1996) Children’s perceptions of peer influence on eating concerns. Behav Ther 27:25–39. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(96)80033-5

Amaya A, Mancilla JM, Alvarez GL, Ortega M, Bautista ML (2011) Propiedades psicométricas del Inventario de Influencia de Pares sobre la Preocupación Alimentaria. Rev Mex Trastor Alimentar 2:82–93. http://journals.iztacala.unam.mx/index.php/amta/article/viewFile/187/204. Accessed Nov 2016

Rosenberg M, Rojas-Barahona C, Zegers B, Förster C, Society and the adolescent self-image (2009) La escala de autoestima de Rosenberg: Validación para Chile en una muestra de jóvenes adultos, adultos y adultos mayores. Rev Med Chil 137:791–800. doi:10.4067/S0034-98872009000600009

Gónzalez-Forteza C, Andrade P, Jiménez A (1997) Recursos psicológicos relacionados con el estrés cotidiano en una muestra de adolescentes mexicanos. Salud Mental 20(1):27–35

Pook M, Tuschen-Caffier B, Brähler E (2008) Evaluation and comparison of different versions of the Body Shape Questionnaire. Psychiatry Res 158:67–73. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2006.08.002

Warren CS, Cepeda-Benito A, Gleaves DH, Moreno S, Rodriguez S, Fernandez MC, Fingeret MC, Pearson CA (2008) English and Spanish versions of the Body Shape Questionnaire: measurement equivalence across ethnicity and clinical status. Int J Eat Disord 41:265–272. doi:10.1002/eat.20492

Schreiber JB, Stage FK, King J, Nora A, Barlow EA (2006) Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: a review. J Educ Res 99:323–337. doi:10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338

Martín-Albo J, Núñez JL, Navarro JG, Grijalvo F (2007) The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: translation and validation in university students. Span J Psychol 10(2):458–467. http://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/SJOP/article/view/SJOP0707220458A/28907. Accessed Nov 2009

Sinclair SJ, Blais MA, Gansler DA, Sandberg E, Bistis K, LoCicero A (2015) Psychometric properties of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: overall and across demographic groups living within the United States. Eval Health Prof 33(1):56–80. doi:10.1177/0163278709356187

Supple AJ, Su J, Plunkett SW, Peterson GW, Bush KR (2013) Factor structure of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. J Cross-Cult Psychol 44(5):748–764. doi:10.1177/0022022112468942

Heron KE, Smyth JM, Akano E, Wonderlich SA (2013) Assessing body image in young children: a preliminary study of racial and developmental differences. SAGE Open 3(1):1–7. doi:10.1177/2158244013478013

Hayden-Wade HA, Stein RI, Ghaderi A, Saelens BE, Zabinski MF, Wilfley DE (2012) Prevalence, characteristics, and correlates of teasing experiences among overweight children vs. non-overweight peers. Obes Res 13(8):1381–1392. doi:10.1038/oby.2005.167

Lingren HG (1991) Self-esteem in children. Children and Family. Cooperative Extension Service: CF-12. http://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/oc/freepubs/pdf/CF-12.pdf. Accessed Feb 2016

Pinheiro MC, Mena MP (2014) Padres, profesores y pares: contribuciones para la autoestima y coping en los adolescents. Anal Psicol 30(2):656–666. doi:10.6018/analesps.30.2.161521

Polivy J, Herman CP (2002) Causes of eating disorders. Annu Rev Psychol 53:187–213. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135103

Phares V, Steinberg AR, Thompson JK (2004) Gender differences in peer and parental influences: body image disturbance, self-worth, and psychological functioning in preadolescent children. J Youth Adolesc 33(5):421–429. doi:10.1023/B:JOYO.0000037634.18749.20

McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA (2001) Parent, peer, and media influences on body image and strategies to both increase and decrease body size among adolescent boys and girls. Adolescence 36(142):225–240. https://dro.deakin.edu.au/eserv/DU:30001199/mccabe-parentpeer-2001.pdf. Accesed Nov 2008

Torres P, Evangelista JJ, Martínez-Salgado H (2011) Coexistence of obesity and anemia in children between 2 and 18 years of age in Mexico. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex 68(6):431–437. doi:10.1007/s12126-011-9135-y

Acknowledgements

Funding: PAPIIT IA303616.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Confict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The authors state that the procedures followed were according to the research ethics committee regulations. The protocols of our institution were followed to access participants data and such information was analyzed with the sole purpose of carrying out and disseminate scientific research findings.

Informed consent

All of the participants were informed of the purposes of the research and all of them signed the informed consent form.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Amaya-Hernández, A., Ortega-Luyando, M., Bautista-Díaz, M.L. et al. Children with obesity: peer influence as a predictor of body dissatisfaction. Eat Weight Disord 24, 121–127 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0374-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0374-0