Abstract

Purpose

Sexual minority individuals experience unique minority stressors leading to negative clinical outcomes, including disordered eating. The psychological mediation framework posits that stress related to discrimination, internalized homonegativity, and concealment makes sexual minority individuals more vulnerable to maladaptive coping processes, such as rumination, known to predict disordered eating. The current study examined the influence of sexual minority stressors and rumination on disordered eating, and whether these associations differed between sexual minority men and women. We hypothesized that perceived discrimination, internalized homonegativity, and concealment would be positively associated with disordered eating, and that rumination about sexual minority stigma would mediate these associations.

Methods

One-hundred and sixteen individuals who identified as sexual minorities completed a survey study assessing perceived discrimination, internalized homonegativity, concealment, rumination about sexual minority stigma, and disordered eating.

Results

Discrimination and concealment uniquely predicted disordered eating in both men and women. However, rumination emerged as a significant mediator for concealment and (marginally) for discrimination for men only. Internalized homonegativity was not uniquely associated with rumination or disordered eating for men or women.

Conclusions

Sexual minority men who experience discrimination and conceal their sexual orientation may engage in more disordered eating because they dwell on sexual minority stigma. We propose other potential mechanisms that may be relevant for sexual minority women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sexual minority individuals, or people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or queer (LGBQ), are at a higher risk of disordered eating than heterosexuals [1]. This disparity is most consistent and significant for sexual minority men. The literature on sexual minority women is less clear, with studies finding higher [1] and lower [2] rates of disordered eating as compared to heterosexual individuals. However, few studies have investigated specific social and cognitive factors that contribute to the higher prevalence of disordered eating among sexual minority individuals. Given the negative physical, mental, and social consequences associated with disordered eating, understanding predictors and mechanisms of disordered eating in sexual minority individuals can have important implications for prevention and treatment.

The minority stress theory [3] suggests that the increased amount of stigma-related stress experienced by sexual minority individuals can explain higher rates of psychopathology, including disordered eating. Indeed, GB men [4] and LB women [5] who reported more discrimination (i.e., differential treatment of sexual minority groups by individuals and social institutions) were more likely to engage in disordered eating, and adults with same-sex sexual partners were more likely to have a diagnosed eating disorder [6]. Internalized homonegativity, or the internalization of negative stigmas about sexual minorities, may create cognitive dissonance because people identify as a sexual minority but have negative beliefs about homosexuality [7]. This cognitive dissonance can negatively affect sexual minority individuals’ attitudes and behaviors towards themselves and their bodies [7], leading to increased psychological distress and disordered eating behaviors. Indeed, internalized homonegativity is associated with increased disordered eating among GB men [4] and LBQ women [5]. Finally, concealment of sexual orientation, although often an attempt to avoid stigma, can result in intrusive thoughts and psychological distress [3]. One previous study failed to find a significant correlation between concealment and binge eating in LB women, although concealment contributed to a latent factor of sexual minority stressors that was associated with binge eating [8]. Clearly, more research is needed to examine whether specific sexual minority stressors predict disordered eating among both men and women.

The psychological mediation model [9] posits that sexual minority stressors increase vulnerability to maladaptive coping processes known to predict psychopathology. Rumination is one such process that involves a repetitive focus on causes and consequences of negative moods, and is associated with disordered eating in diverse nonclinical [10] and clinical [11] populations. Rumination also predicts body dissatisfaction and negative affect, which are risk factors for disordered eating [12]. Rumination can occur in response to perceived threats to an individual’s sense of self and well-being [13], and sexual minority stressors clearly constitute one such threat. Indeed, lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals reported more rumination on days when they perceived stigma-related stressors [14]. Among LBQ women, those who experienced more discrimination and internalized homonegativity were also more likely to ruminate [15]. One previous study that applied the psychological mediation framework to examine binge eating among LB women found that a latent variable of emotion-focused coping (including rumination, self-blame, and catastrophizing) explained the relationship between sexual minority stressors (including internalized homonegativity and concealment) and binge eating [8]. However, whether rumination is a unique mechanism of sexual minority stressors, and whether this mediational relationship holds for general disordered eating across genders, remains unknown.

GB men are more likely than LB women to experience sexual victimization and hate crimes [16] and engage in disordered eating [1]. Thus, whether mechanisms of the relationship between sexual minority stressors and psychological health differ between men and women also warrants investigation. Whereas some previous studies found stronger associations between sexual minority stressors and outcomes among gay men than lesbian women [17], others found stronger associations among LB women than GB men [18]. Gender effects on relationships between rumination and psychological outcomes are also unclear. Gordon et al. [19] found no gender differences in the relationship between rumination and binge eating among undergraduates. However, rumination more strongly predicted aggression and alcohol-related problems, but not depressive symptoms, for males than females [20, 21]. Given these mixed findings, additional research is needed to clarify whether rumination differentially influences disordered eating for men and women.

The current study examined associations between sexual minority stressors (discrimination, internalized homonegativity, concealment), rumination, and disordered eating among sexual minority individuals. Because the causal model assumes that sexual minority stressors lead to rumination about those stressors, we examined rumination specifically about sexual minority stigma. We hypothesized that sexual minority stressors would be positively associated with stigma-related rumination and disordered eating, and that rumination would mediate the relationships between these stressors and disordered eating. We also explored whether gender moderates this mediational model. As there are inconsistent findings on gender differences in the bivariate relationships between sexual minority stressors, rumination, and disordered eating, we did not have specific hypotheses about the effects of gender.

Methods

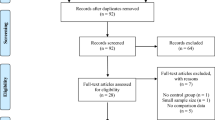

Participants and procedure

The sample consisted of 116 sexual minority individuals ages 18 to 40 (M = 24.8, SD = 5.35) who identified as male (59.5%) or female. Among male participants, 91% identified as gay, 7% as bisexual, and 1% as “other” (queer, pansexual, asexual). Among female participants, 39% identified as lesbian, 41% as bisexual, and 20% as “other”. Participants predominantly identified as European American/White (90%); 77% were undergraduate students, 17% were graduate students, and 7% were not currently in school.

The majority (79%) of participants were recruited from the research website of the Consortium of Higher Education LGBT Resource Professionals, representing colleges and universities all over the United States. These participants received a $5 Amazon gift card as compensation. All other participants were recruited at a Northeastern public liberal arts college and received either psychology course credit or a $5 Amazon gift card. Participants from the LGBT listserv were an average of 7.4 years older than participants from the college, and were more likely to identify as male, gay, and European American/White (all p’s < .001). Participants from the college were more likely to identify as bisexual and Asian/Asian American.

Before completing the 30-min online questionnaires, all participants provided informed consent. All measures, and the order of items within each measure, were presented in a randomized order. The college’s IRB approved all research and recruitment procedures.

Measures

Sexual minority discrimination. The nine-item Experiences of Everyday Discrimination scale [22] assesses the frequency of daily discrimination related to sexual orientation (e.g., you are treated with less respect than other people are). Respondents indicate the frequency of each type of discrimination on a 6-point scale from 1 (never) to 6 (almost every day). This scale correlates with other measures of discrimination [23]. Higher averaged scores indicate more perceived discrimination. In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .97.

Internalized homonegativity. The three-item Internalized Homonegativity subscale of the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identity Scale (LGBIS) [24] assesses the extent to which participants reject their sexual orientation, are uneasy about the same-sex desires, and seek to avoid same-sex attractions. All items are rated on a six-point Likert scale, with higher averaged scores indicating more internalized homonegativity. This subscale correlates with ego-dystonic homosexuality [24]. In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .92.

Concealment. The three-item Concealment Motivation subscale of the LGBIS [24] assesses the extent to which participants conceal their sexual orientation and prefer to keep it private. All items are rated on a six-point Likert scale, with higher averaged scores indicating more concealment. This subscale correlates with other measures of self-concealment and outness [24]. In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .81.

Rumination. We modified the Rumination about Interpersonal Offences Scale [25] to create a new measure that assesses rumination specifically about perceived sexual minority stigma. The original 6-item scale asks participants whether they recently ruminated about an instance when they were hurt by someone. We reworded the original questions to assess rumination about sexual minority stigma (e.g., “I can’t stop thinking about how people of my sexual orientation have been discriminated against”). Participants responded to all items on a 7-point Likert scale, and higher averaged scores indicated more rumination. To examine the validity of this measure, participants also completed the 19-item Anger Rumination Scale [26], which has strong evidence of convergent validity and is commonly used in the rumination field. Rumination about sexual minority stigma was significantly correlated with angry rumination (r = .63, p < .01), suggesting initial convergent validity of our new measure. In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .96.

Disordered eating. The 26-item Eating Attitudes Test [27] assesses disordered eating. Participants rate each item (e.g., “have the impulse to vomit after meals”) on a scale from “never” to “always”. Following the original scoring method [27], the three least extreme responses (never, rarely, sometimes) were scored as zero, and more extreme responses (often, usually, always) were scored from 1 to 3. Higher averaged scores indicate more eating disorder symptoms. This measure correlates with other measures of eating disorder symptoms [27] and has been used in research with sexual minority individuals [4, 7, 28]. In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .97.

Data analysis

Our primary analyses tested path models using the MPlus program version 7.0 [29], with the missing-at-random assumption [30] and maximum likelihood estimation. We assessed overall model fit using the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the χ 2 statistic, and the comparative fit index (CFI). General rules of thumb for adequate model fit include a CFI close to 1, a non-significant χ 2, and small RMSEA (<.05).

We created two path models. We first built a total effects model (see Fig. 1) with direct paths from the independent variables (discrimination, internalized homonegativity, concealment) to the dependent variable (disordered eating). We then added rumination about sexual minority stigma as a mediator between each independent variable and disordered eating (see Fig. 2). All variables were modeled as single observed variables. In both models, the independent variables were allowed to covary.

Unconstrained multi-group total effects model with sexual minority stressors predicting disordered eating, separately by gender. Unstandardized coefficients (and SEs) to the left of the slash are for men; values to the right are for women. Significant coefficients (p < .05) are in bold. Method of recruitment was included as a covariate

Unconstrained multi-group mediational model with rumination mediating the associations between sexual minority stressors and disordered eating, separately by gender. Unstandardized coefficients (and SEs) to the left of the slash are for men; values to the right are for women. Significant coefficients (p < .05) are in bold. Method of recruitment was included as a covariate

To explore potential gender differences, we examined whether these two models differed for sexual minority men and women. We ran multi-group models with the estimated path coefficients and residual variance for the dependent variable either (a) constrained to be the same or (b) allowed to vary across gender (male vs. female). So that the unconstrained models were over-identified; we set the correlation between discrimination and internalized homonegativity to be the same for both genders. We compared model fit using χ 2 difference tests.

We examined mediation by calculating indirect effects of three independent variables (discrimination, internalized homonegativity, and concealment) via rumination on disordered eating. The significance of indirect effects was examined using 5000 bootstrap samples [31]. We calculated the bootstrap estimates and bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals for each indirect effect; a confidence interval that does not include zero indicates a significant effect of mediation.

Results

Descriptive statistics

All variables were normally distributed (skew values <.90). Descriptive statistics and correlations are reported in Table 1. We first examined differences by method of recruitment (LGBT listserv vs. campus student). Participants from the LGBT listserv reported more perceived discrimination (t (114) = 7.04, p < .001, d = 1.30), internalized homonegativity (t (114) = 4.58, p < .001, d = 1.05), concealment (t (114) = 2.21, p = .03, d = 0.49), rumination about sexual minority stigma (t (114) = 6.07, p < .001, d = 1.40), and disordered eating (t (114) = 4.91, p < .001, d = .89) than participants from the college. Because of these differences, we controlled for method of recruitment in analyses below.

Controlling for method of recruitment, men (M = 4.18, SD = 1.12) reported more internalized homonegativity than women (M = 3.09, SD = 1.53), F (1, 114) = 9.37, p = .003. Participants who identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual reported more perceived discrimination (F (3, 111) = 3.38, p = .02) and internalized homonegativity (F (3, 111) = 10.20, p < .001) than those who identified as “other.” There were no other differences by gender or sexual orientation.

In the entire sample, greater discrimination, internalized homonegativity, and concealment were significantly correlated with more rumination and disordered eating. Rumination was significantly correlated with worse disordered eating. Controlling for method of recruitment did not change the size, direction, or significance of correlations (not shown).

Total effects analyses

We first fitted a model with direct paths from each of the sexual minority stressors to disordered eating. The stressors were allowed to covary, and method of recruitment was a covariate. The model for the entire sample was just identified. Discrimination (β = .46, p < .001) and concealment (β = .30, p < .001) significantly predicted disordered eating but internalized homonegativity did not (β = .09, p = .35). The three independent variables were significantly intercorrelated (all β’s > .47, p’s < .001).

We next tested whether these results differed between men versus women. The multi-group model with all coefficients constrained across gender was a poor fit, χ 2 (11) = 38.23, p < .001, CFI = .91, RMSEA = .21. By contrast, the unconstrained multi-group model was an excellent and significantly better fit, χ 2 (1) = .74, p = .39, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, Δχ 2 (10) = 37.49, p < .01. Therefore, the coefficients for sexual minority men and women groups cannot be assumed to be the same. For both men and women, discrimination and concealment significantly predicted disordered eating, but internalized homonegativity did not (see Fig. 1). For men but not women, discrimination and concealment were significantly correlated.

Mediation analyses

We next created a mediation model with paths from the independent variables (discrimination, internalized homonegativity, concealment) to the mediator (rumination) and dependent variable (disordered eating). As before, the independent variables were allowed to covary, and method of recruitment was a covariate. The model for the entire sample was just identified. Discrimination (β = .58, p < .001) and concealment (β = .23, p < .01), but not internalized homonegativity (β = −.12, p = .21), significantly predicted rumination about sexual minority stigma. In turn, rumination significantly predicted disordered eating, β = .33, p < .001. The direct effects of discrimination (β = .27, p < 01) and concealment (β = .22, p < .01), but not internalized homonegativity (β = .13, p = .16), were significant. Estimated indirect effects and their confidence intervals indicated that rumination significantly mediated the paths between discrimination and concealment (but not internalized homonegativity) and disordered eating (see Table 2).

We then examined whether these results differed in men versus women. The constrained multi-group model was a poor fit, χ 2 (16) = 61.27, p < .001, CFI = .89, RMSEA = .22. By contrast, the unconstrained multi-group model was an excellent and significantly better fit, χ 2 (1) = .74, p < .001, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, Δχ 2 (15) = 60.53, p < .01. Therefore, the path coefficients differed meaningfully by gender (see Fig. 2). For men, discrimination and concealment (but not internalized homonegativity) significantly predicted rumination, and rumination predicted disordered eating. The indirect effect (see Table 2) for concealment was significantly different from zero, suggesting a significant effect of mediation. For women, discrimination (but not concealment or internalized homonegativity) predicted rumination, but rumination did not predict disordered eating. No indirect effects were significantly different from zero.

Discussion

The current study examined whether rumination mediated the associations between several specific sexual minority stressors and disordered eating. Unlike previous studies that measured trait depressive and angry rumination, we measured rumination specifically about sexual minority stigma. Additionally, we examined these associations in sexual minority men and women. We extend on previous literature with several interesting findings.

In line with the minority stress theory [3], sexual minority men and women who reported more discrimination, concealment, and internalized homonegativity were more likely to engage in disordered eating. However, our path model revealed that only perceived discrimination and concealment uniquely predicted disordered eating. These results replicate previous research that sexual minority discrimination is associated with disordered eating. Importantly, we extend upon previous findings [8] by demonstrating the unique association between concealment and general disordered eating among both men and women. As concealment is mentally, physically, and emotionally draining [32], individuals who struggle with concealment of their sexual identity may be more likely to engage in disordered eating.

Within the entire sample, rumination mediated the effects of discrimination and concealment on disordered eating, supporting the psychological mediation model [9]. However, we found meaningful gender differences in these mediational relationships. Sexual minority men with higher levels of concealment endorsed more rumination about sexual minority stigma, which was then associated with greater disordered eating. The indirect effect of discrimination on disordered eating via rumination was also marginally significant for men. Discrimination was also associated with concealment among sexual minority men, suggesting that discrimination can lead men to conceal their sexual orientation, in line with the minority stress model [3]. Although we cannot make causal conclusions from cross-sectional data, we suggest that experiences of discrimination and the perceived need for concealment make men brood about sexual minority stigma. Just as individuals may engage in disordered eating as an escape from negative emotions [33], men who ruminate about sexual minority stigma may use disordered eating behaviors as a coping mechanism to escape unpleasant thoughts and related emotions.

Interestingly, rumination did not mediate the associations between sexual minority stressors and disordered eating for women. These results likely reflect the non-significant association between rumination and disordered eating for women. As previous research linking rumination with disordered eating among women assessed general depressive rumination in primarily heterosexual samples [34], these established associations may not apply to rumination about sexual minority stigma. Future research might examine depressive rumination as a mechanism of sexual minority stressors in women. Moreover, self-objectification, or the process by which women internalize sexually objectifying messages about their bodies, predicts disordered eating among sexual minority women [28] and may also mediate the association between minority stressors and disordered eating in this population. Finally, future research should explore mechanisms such as optimism, self-compassion, and social support among sexual minority individuals, as these factors are associated with disordered eating [10, 12].

For both men and women, internalized homonegativity did not uniquely predict rumination or disordered eating. Thus, individuals who internalize negative sexual stigma may not ruminate about the unfairness of this stigma. Instead, they may engage in self-blame [8] or self-focused rumination about their own flaws. This self-blame may in turn manifest through body shame and appearance dissatisfaction, rather than disordered eating [4, 7]. Future research might examine these and other potential mechanisms of the influence of internalized homonegativity on eating-related outcomes in sexual minority individuals.

This study has several limitations. First, our measure of disordered eating precludes any conclusions about diagnosable eating disorders. However, the EAT-26 is a well-validated measure that differentiates between nonclinical individuals and those with diagnosable eating disorders [35] and is frequently used in research with sexual minority individuals. Nevertheless, future research should examine our hypotheses in a clinical sample, to determine whether sexual minority stressors and rumination about stigma predict diagnosable eating disorders. Participants also differed by method of recruitment on all of our variables. To address this, we controlled for method of recruitment in the path models and found that sample differences did not explain the observed associations. However, we did not have information about the origin of participants recruited through the online sample, and were unable to examine whether sexual minority stigma and its effects differed between regions of the United States. Additionally, our sample size did not allow us to examine whether the associations among study variables varied by self-identified sexual orientation or make more fine-grained distinctions between various identities (e.g., queer vs. questioning vs. pansexual). Finally, due to the cross-sectional nature of our study, we cannot determine temporal associations or make assumptions about causality. In particular, we cannot know whether disordered eating in fact resulted from rumination and sexual minority stressors. To address this, future research can use longitudinal or experimental methodology. However, given that we asked specifically about ruminating in response to sexual minority stigma, participants likely ruminated as a result of their experiences with sexual minority stressors.

Our measurement of rumination about sexual minority stigma is both a strength and limitation of the study. As an adapted measure, its specific psychometric properties are unknown. However, this scale correlated with a well-established angry rumination measure, suggesting initial convergent validity. Moreover, this scale allowed us to directly assess the theoretical assumption that individuals ruminate in response to sexual minority stressors, whereas previous research in this area has examined general depressive and angry rumination. To gain a better understanding of rumination about sexual minority stigma, we encourage future research in the field to continue measuring rumination about perceived and felt stigma.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes important new information about sexual minority stressors and disordered eating in sexual minority individuals. Perceived discrimination and concealment were related to disordered eating among both men and women. For men, ruminating about sexual minority stressors partly explained these relationships. These findings can inform eating disorder interventions for sexual minority men. Specifically, it may be helpful for clinicians who work with these patients to identify and reduce rumination about sexual minority stigma. Several treatments such as rumination-focused cognitive behavioral therapy [36] and mindfulness training [37] reduce rumination. Examining whether these treatments reduce rumination about sexual minority stigma and subsequent disordered eating can be an important next step in the prevention of disordered eating among sexual minority men.

References

Matthews-Ewald MR, Zullig KJ, Ward RM (2014) Sexual orientation and disordered eating behaviors among self-identified male and female college students. Eat Behav 15(3):441–444. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.05.002

Schneider JA, O’Leary A, Jenkins SR (1995) Gender, sexual orientation, and disordered eating. Psychol Health 10(2):113–128. doi:10.1080/08870449508401942

Meyer IH (2003) Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 129(5):674–697. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Wiseman MC, Moradi B (2010) Body image and eating disorder symptoms in sexual minority men: A test and extension of objectification theory. J Couns Psychol 57(2):154–166. doi:10.1037/a0018937

Watson LB, Grotewiel M, Farrell M, Marshik J, Schneider M (2015) Experiences of sexual objectification, minority stress, and disordered eating among sexual minority women. Psychol Women Q 39(4):458–470. doi:10.1177/0361684315575024

Frisell T, Lichtenstein P, Rahman Q, Långström N (2010) Psychiatric morbidity associated with same-sex sexual behaviour: Influence of minority stress and familial factors. Psychol Med 40(2):315–324. doi:10.1017/S0033291709005996

Reilly A, Rudd NA (2006) Is internalized homonegativity related to body image? Fam Consum Sci Res J 35(1):58–73. doi:10.1177/1077727X06289430

Mason TB, Lewis RJ (2015) Minority stress and binge eating among lesbian and bisexual women. J Homosex 62(7):971–992. doi:10.1080/00918369.2015.1008285

Hatzenbuehler ML (2009) How does sexual minority stigma ‘get under the skin’? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol Bull 135(5):707–730. doi:10.1037/a0016441

Mason TB, Lewis RJ (2016) Examining social support, rumination, and optimism in relation to binge eating among Caucasian and African–American college women. Eat Weight Disord. doi:10.1007/s40519-016-0300-x

Naumann E, Tuschen-Caffier B, Voderholzer U, Caffier D, Svaldi J (2015) Rumination but not distraction increases eating-related symptoms in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. J Abnorm Psychol 124(2):412–420. doi:10.1037/abn0000046

Maraldo TM, Zhou W, Dowling J, Vander Wal JS (2016) Replication and extension of the dual pathway model of disordered eating: the role of fear of negative evaluation, suggestibility, rumination, and self-compassion. Eat Behav 23:187–194. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.10.008

Martin LL, Tesser A (1996) Some ruminative thoughts. In: Wyer RJ, Wyer RJ (eds) Ruminative thoughts. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc, Hillsdale, pp 1–47

Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J (2009) How does stigma ‘get under the skin’? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychol Sci 20(10):1282–1289. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x

Szymanski DM, Dunn TL, Ikizler AS (2014) Multiple minority stressors and psychological distress among sexual minority women: the roles of rumination and maladaptive coping. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers 1(4):412–421. doi:10.1037/sgd0000066

Herek GM (2009) Hate crimes and stigma-related experiences among sexual minority adults in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a national probability sample. J Interpers Violence 24(1):54–74. doi:10.1177/0886260508316477

Feinstein BA, Goldfried MR, Davila J (2012) The relationship between experiences of discrimination and mental health among lesbians and gay men: An examination of internalized homonegativity and rejection sensitivity as potential mechanisms. J Consult Clin Psychol 80(5):917–927. doi:10.1037/a0029425

Dewaele A, Van Houtte M, Vincke J (2014) Visibility and coping with minority stress: A gender-specific analysis among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals in Flanders. Arch Sex Behav 43(8):1601–1614. doi:10.1007/s10508-014-0380-5

Gordon KH, Holm-Denoma JM, Troop-Gordon W, Sand E (2012) Rumination and body dissatisfaction interact to predict concurrent binge eating. Body Image 9(3):352–357. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.04.001

McLaughlin KA, Aldao A, Wisco BE, Hilt LM (2014) Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor underlying transitions between internalizing symptoms and aggressive behavior in early adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol 123(1):13–23. doi:10.1037/a0035358

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Harrell ZA (2002) Rumination, depression, and alcohol use: tests of gender differences. J Cogn Psychother 16(4):391–403. doi:10.1891/jcop.16.4.391.52526

Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB (1997) Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J Health Psychol 2(3):335–351. doi:10.1177/135910539700200305

Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM (2005) Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med 61(7):1576–1596. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006

Mohr JJ, Kendra MS (2011) Revision and extension of a multidimensional measure of sexual minority identity: the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identity Scale. J Couns Psychol 58(2):234–245. doi:10.1037/a0022858

Wade NG, Vogel DL, Liao KY, Goldman DB (2008) Measuring state-specific rumination: development of the Rumination About an Interpersonal Offense Scale. J Couns Psychol 55(3):419–426. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.55.3.419

Sukhodolsky DG, Golub A, Cromwell EN (2001) Development and validation of the Anger Rumination Scale. Pers Individ Differ 31(5):689–700. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00171-9

Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE (1982) The eating attitudes test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med 12(4):871–878. doi:10.1017/S0033291700049163

Brewster ME, Velez BL, Esposito J, Wong S, Geiger E, Keum BT (2014) Moving beyond the binary with disordered eating research: a test and extension of objectification theory with bisexual women. J Couns Psychol 61(1):50–62. doi:10.1037/a0034748s

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998) Mplus user’s guide (1998–2012), 7th edn. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA

Little R, Rubin D (1987) Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley, New York

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2008) Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 40:879–891. doi:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Critcher CR, Ferguson MJ (2014) The cost of keeping it hidden: decomposing concealment reveals what makes it depleting. J Exp Psychol Gen 143(2):721–735. doi:10.1037/a0033468

Heatherton TF, Baumeister RF (1991) Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychol Bull 110:86–108

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S (2008) Rethinking rumination. Perspect Psychol Sci 3:400–424. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088

Kashubeck-West S, Mintz LB, Saunders KJ (2001) Assessment of eating disorders in women. Couns Psychol 29(5):662–694. doi:10.1177/0011000001295003

Watkins E, Scott J, Wingrove J, Rimes K, Bathurst N, Steiner H, Malliaris Y (2007) Rumination-focused cognitive behaviour therapy for residual depression: a case series. Behav Res Ther 45(9):2144–2154. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2006.09.018

Ramel W, Goldin PR, Carmona PE, McQuaid JR (2004) The effects of mindfulness meditation on cognitive processes and affect in patients with past depression. Cognit Ther Res 28:433–455. doi:10.1023/B:COTR.0000045557.15923.96

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, S.B., Borders, A. Rumination mediates the associations between sexual minority stressors and disordered eating, particularly for men. Eat Weight Disord 22, 699–706 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0350-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0350-0