Abstract

Background

There are limiting studies evaluating the weight self-stigma and its association with eating disorders and health concerns. However, no study is available evaluating weight self-stigma and its determinants among reproductive age women in Iran. The aim of this study was to evaluate weight self-stigma and its association with quality of life and psychological distress among overweight and obese Iranian women.

Materials and methods

The current cross-sectional study was performed among 170 women aged 17–45 years referring to health centers of Tabriz-Iran. Anthropometric assessments were performed. Weight self-stigma was assessed by weight self-stigma questionnaire (WSSQ). Evaluation of quality of life and psychological distress was performed using SF-12 and general health questionnaires (GHQ-12), respectively. Analysis of data was performed by multivariate hierarchical regression analysis using SPSS 18 software.

Results

In this study, the multivariate hierarchical regression analysis revealed that being married and having low total weight self-stigma and fear of enacted stigma (FES) scores were associated with better physical component summary scores (p < 0.05). Whereas, younger ages and lower total weight self-stigma scores were associated with better mental component summary scores. In addition, lower weight self-stigma total scores and lower self-devaluation scores were predictors of lower psychological distress.

Conclusion

Our results indicated the negative impacts of weight self-stigma on quality of life and psychological distress among overweight and obese women. Since weight stigma might be a potent barrier of obese individuals to engage in health promoting behaviors, therefore, the results of the current study further warrants the need for developing interventional strategies to reduce the adverse impacts of weight stigma on quality of life via including the reduction of weight self-stigma as a key therapeutic goal in obesity treatment programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obesity stigma is debilitating and arises from the increasing prevalence of negative bias toward obese individuals while reflected in discriminatory practices across employment, healthcare and education [1]. Therefore, effects of increased focus on body weight in health care may be the alienation and humiliation of these patients. Obese individuals are perceived as weak, indolent, untidy, lack of self-confidence, and lack of any motivation to improve their health status [2]. Obviously, this negative social view to obesity and filling stigmatized has been implicated in the development of low self-esteem, depressive symptoms, feeling of helpless, isolation and poor general psychological functions among obese individuals [1, 3].

The term “stigma” describes physical characteristics or character traits that mark the bearer as having low social value [4]. Stigma is a multidimensional concept. Enacted stigma refers to directly experienced social discrimination in areas, such as housing, social relationship and employment. In addition, people are frequently aware of stigma directed at others who share similar characteristics; fear it being directed at them. Self-stigma or internalized stigma refers to this self-devaluation and fear of enacted stigma as a result of one’s identification with a stigmatized group [5].Weight self-stigma is associated with numerous negative psychosocial outcomes including mood disturbance, body image concern, drive for thinness, binge eating, and decreased self-esteem [6, 7].

The prevalence of weight-based stigma and discriminations are increasing throughout the developed societies including USA [2]. Studies have found that stigma against obesity is one of the most common forms of stigma, even comparable with the rates of perceived racism among women in certain populations [8]; according to previous reports, women had higher levels of weight self-stigma than men and accordingly among women, weight self-stigma was more strongly associated with disordered eating-related attitudes and depressive symptoms than in men [9, 10].

Although in the past decades excess weight was not a negative experience in the Middle Eastern countries including Iran, however, change in lifestyle, urbanization and exposure to mass media have extreme effects on body weight concerns in developing countries; in these countries, urbanization and western influences are probably the greatest force to change the general beliefs about obesity and in middle income-developing countries fat stigma is rapidly increasing [11]. However, in Iran, no report of weight self-stigma or its ingredients including self-devaluation or fear of enacted stigma and their determinants among overweight and obese women is available. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the body weight self-stigma and fear of enacted stigma and their association with quality of life and psychological distress in reproductive age women.

Methods and materials

Subjects

This study was conducted among reproductive age free-living women who regularly attended to urban public health centers in northwest of Iran in May through September 2015. A total of three health centers in Tabriz city of East Azerbaijan province were selected and one hundred seventy women aged 17–45 years were enrolled. Information about age, educational attainment, physical activity, occupation, smoking status, marital status and the history of previous disease including type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, thyroid and renal dysfunction and other disease were obtained by face to face interview from participants. The women referring to health care centers in Iran are representative of all of the Iranian reproductive age women. This is mostly because of comprehensiveness of health care settings in Iran, especially for target groups of reproductive age women, children and neonates. Most of the demographic characteristics of these women including their educational level and socio-cultural characteristics are similar of total population.

Measurements and classifications

Weight was measured with a balanced beam scale to the nearest 0.5 kg and height to the nearest 0.5 cm with a wall scale while subjects wearing light clothes and no shoes. BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m)2. Overweight and obesity were defined as having BMI between 25–29.9 and ≥30 kg/m2, respectively [12]. Educational attainment was mentioned as one’s total education years throughout her life.

Weight self-stigma measurement

Stigma associated with being overweight or obese was measured using a weight self-stigma Questionnaire (WSSQ). The questionnaire previously generated by Lillis et al. [13] includes two distinct but correlated subscales of self-devaluation subscale (items 1–6) and fear of enacted stigma subscale (items 7–12). These items in self-devaluation subscale include fear of being overweight, encountering with weight problems, feeling guilty because of weight problems, feeling weakness because of obesity and not to have self control to maintain a healthy weight. In the fear of enacted subscale, the items include feeling insecure about people thoughts of being obese, people’s discrimination about having weight problems and not to have optimum social relationships. The items of WSSQ are rated on the scales of 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Sum scores are calculated for the full scale and each subscale. We validated the questionnaire and achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75 and 0.78 for subscales of WSSQ, respectively; also the total items achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86. Higher scores indicate higher self-stigma.

Quality of life assessment

Health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) was measured using a short-form 12-item health survey (SF-12) questionnaire [14]. The questionnaire has been previously validated by Montazeri et al. [15] for use in Iranian population. The SF-12 is a generic measure and does not target a specific age or disease group. It has been developed to provide a shorter and valid alternative to the SF-36. The SF-12 includes 12 questions hypothesized to form two distinct clusters related to physical and mental health known as physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) [16]. These items totally are categorized in eight subscales of: physical functioning (evaluating the limitations doing moderate activities and climbing several flights of stairs), role limitations due to physical problems (evaluating the less accomplishment than one would like to achieve and limitation in kind of work or other activities), bodily pain (evaluating the pain interference with one’s normal work), general health (evaluating the general health perception), vitality (about having energy), social functioning (items evaluating the interference of physical health or emotional problems with one’s social activities), role limitations due to emotional problems (evaluating less accomplishment than one would like to achieve and not being careful in doing activities as usual) and perceived mental health (feeling calm or peaceful and feeling sad or blue). The validated form achieved a Cronbach’s alpha for PCS-12 and MCS-12 as 0.73 and 0.72, respectively [15]. In this study, we also achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75 and 0.76 for for PCS-12 and MCS-12, respectively. High scores of SF-12, indicate better quality of life.

Psychological distress assessment

Psychological distress was measured by a 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), a self-administered screening tool for assessing psychological distress. We used a validated version of GHQ-12 with an acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = 0.87), previously validated for use in Iranian population [17]. We also achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82 for GHQ-12 in our study. Each item is rated on a four-point scale (less than usual, no more than usual, fairly more than usual and much more than usual). General Likert scoring method was used to score the GHQ-12 questionnaires. In this method, the items of GHQ-12 are rated on the scales of 0 (less than usual) to 3 (much more than usual). A range of 0–36 is given to the items and means of GHQ-12 scores are used in the analysis. Sum scores are calculated for the full scale and each subscale. Lower scores denote less psychological distress. The items of GHQ-12 included: being able to concentrate, losing much sleep, playing useful part, capable to making decisions, being under stress, could not overcome difficulties, enjoying normal activities, face up to problems, feeling unhappy and depressed, losing confidence, thinking of self as worthless and feeling reasonably happy.

Statistical analysis

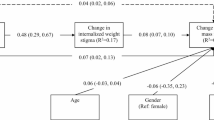

Statistical analysis was performed with Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS 18 for windows, SPSS Inc® headquarter, Chicago, USA). Normality of data was analyzed by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. All of the continuous variables were normally distributed. Multivariate hierarchical regression analyses (balanced design) were performed to examine the association between the outcome measures (i.e., physical component summary, mental component summary and general health questionnaire) and the potential explanatory factors (i.e., socio-demographic factors, physical activity, body mass index and marital status). The entry of the variables into the models was as follows: Model (1) age, marital status, BMI and educational attainment; Model (2) age, marital status, BMI, educational attainment, total weight self-stigma score and its subscales as fear of enacted stigma and self-devaluation values. p values less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

Results

A total of 170 women mean aged 31.29 ± 7.43 years were enrolled in this study. General characteristics of study population are presented in Table 1. Participants were more likely to be overweight, married and to have sedentary life style. Moreover, most of the participants were never smokers (72.4 %).

Univariate analyses showed that marital status and fear of enacted stigma were significantly associated with the physical component summary; age and weight self-stigma total score were significantly associated with the mental component summary, and weight self-stigma total score and self-devaluation scores were significantly associated with GHQ-12 score, respectively (Table 2). Other variables were not in significant relationship with outcomes including PCS, MCS and GHQ-12 scores (p > 0.05).

In multivariate hierarchical regression analysis (Table 3), being married and having low fear of enacted stigma and low weight self-stigma total score were associated with better physical component summary scores (p < 0.05). Whereas, younger age and lower total weight self-stigma scores were associated with better mental component summary scores. In determining the predictors of psychological distress, lower ages, lower weight self-stigma total scores and lower SD scores were predictors of lower psychological distress.

Discussion

This study is the first study evaluating the weight self-stigma and its association with quality of life and psychological distress among overweight and obese Iranian women. In this study, we found that having low weight self-stigma, low fear of enacted stigma and younger ages were associated with better quality of life among overweight and obese women. In addition, having low weight self-stigma and self-devaluation were associated with lower psychological distress in this population.

Lower total weight self-stigma and fear of enacted stigma scores were associated with better quality of life in the present study. Consistent with our findings, in the Lillis J study weight self-stigma scores were in strong relationship with lower obesity related quality of life [13]. In the Latner study [18], internalized weight stigma was significantly correlated with health impairment in both physical (r = −0.25) and mental (r = −0.48) domains in overweight and obese adults; in multivariate analyses controlling for body mass index, age, and other physical health indicators, internalized weight bias significantly and independently predicted impairment in both physical (β = −0.31) and mental (β = −0.47) health. These negative association between weight self-stigma and quality of life may arise from higher stress associated with weight self-stigma; it has been proposed that the stress associated with weight self-stigma may have a significant negative impact on cardiovascular health and metabolic abnormalities, which could potentially lead to poorer health and weight gain and unhealthy coping behaviors, such as smoking or alcohol use [19, 20].

More interestingly, according to our findings, having low weight self-stigma scores was associated with lower psychological distress. Weight self-stigma has well-known psychological harms in obese individuals. Research has shown that overweight and obese individuals are perceived not just unfavorably, but actually provoke more feelings of disgust than 12 historically stigmatized groups (homeless individuals, persons with mental illness, etc.) [21–23]. Obese individuals with fear of enacted stigma may experience high level of stress which can contribute to impaired cognitive function and ability to effectively communicate [24]. High exposure to stress hormones has long-term physiological health effects including heart disease, stroke, depression, etc. In the study by O’Brien [25], psychological distress was a potent positive mediator of the relationship between weight stigma and disordered eating behaviors even after adjusting for the confounding effects of age, gender and BMI among undergraduate university students.

In this study, having younger ages was associated with better quality of life as presented by PCS and MCS. Previous reports have shown that younger women had greater concern for body shape and body weight dissatisfaction [26]. Same as our results, in the study by Tajvar et al. [27] increasing age was associated with lower scores of MCS and PCS in Tehranian elderly population. In other study by Schunk et al. [28] older ages was associated with lower quality of life in diabetic patients.

In our study, being married was also associated with better quality of life in overweight and obese women. According to previous reports, married people have improved mental health compared with those who are single, divorced, or bereaved due to the social relationship with the spouse [29, 30]. Same as our results in the study by Han et al. [31], married people over 30, had better quality of life compared with those in different other marriage status including single, divorced, separated or bereaved.

Our study had several limitations; first of all the cross-sectional design of the study make it difficult to better clarify the cause and effect relationship between variables. Moreover, analyzing the nutritional status and dietary habits could help for further evaluation of the possible relationship between nutritional status and weight self-stigma and to clarify the negative impacts of weight self-stigma on intake of energy and nutrients. Finally, this study included only women as target group. This may limit the generalizability of the findings. However, the current study was worthwhile because it was the first study evaluated the weight self-stigma and its association with quality of life and psychological distress among overweight and obese Iranian women.

In conclusion, our findings revealed that higher weight stigma denotes higher psychological distress and lower quality of life among overweight and obese women. Our findings demonstrate that body weight stigmatization is a health problem not only in Western societies, but also in Eastern and developing countries, possibly due to the diffusion of Western stigmatizing norms, urbanization, and exposure to mass media. Our study further reveals that research on stigma reduction interventions should be aware of the varying social, cultural, and national contexts in which health interventions must be embedded on the ground [32]. Stigma reduction takes place not only at the level of individuals, but also at the level of social and institutional policies that may shift stigmatizing cultural constructions over the long-term [33]. Therefore, researchers must identify individual-level and societal-level interventional strategies and programs that include the reduction of weight self-stigma as a key therapeutic goal of obesity treatment programs.

References

Puhl R, Brownell KD (2001) Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obes Res 9:788–805. doi:10.1038/oby.2001.108

Puhl R, Suh Y (2015) Stigma and eating and weight disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep 17:10–15. doi:10.1007/s11920-015-0552-6

Wott CB, Carels RA (2010) Overt weight stigma, psychological distress and weight loss treatment outcomes. J Health Psychol 15(4):608–614. doi:10.1177/1359105309355339

Pescosolido BA, Martin JK (2015) The stigma complex. Annu Rev Sociol 41:87–116. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-071312-145702

Link BG, Phelan JC (2001) Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol 27:363–385. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

Vartanian LR, Porter AM (2016) Weight stigma and eating behavior: a review of the literature. Appetite. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2016.01.034

Durso LE, Latner JD, White MA, Masheb RM, Blomquist KK, Morgan PT, Grilo CM (2012) Internalized weight bias in obese patients with binge eating disorder: associations with eating disturbances and psychological functioning. Int J Eat Disord 45(3):423–427. doi:10.1002/eat.20933

Puhl R, Andreyeva T, Brownell K (2008) Perceptions of weight discrimination: prevalence and comparison to race and gender discrimination in America. Int J Obes 32:992–1000. doi:10.1038/ijo.2008.22

Boswella RG, White MA (2015) Gender differences in weight bias internalisation and eating pathology in overweight individuals. Adv Eat Disord 3(3):259–268. doi:10.1080/21662630.2015.1047881

O’Hara L, Tahboub-Schulte S, Thomas J (2016) Weight-related teasing and internalized weight stigma predict abnormal eating attitudes and behaviors in Emirati female university students. Appetite. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2016.01.019

Brewis AA, Wutich A, Cowden AF, Soto IR (2011) Body norms and fat stigma in global perspective. Curr Anthropol 52(2):269–276. doi:10.1086/659309

Farhangi MA, Keshavarz SA, Eshraghian M, Ostadrahimi A, Saboor-Yaraghi AA (2013) Vitamin A supplementation, serum lipids, liver enzymes and C-reactive protein concentrations in obese women of reproductive age. Ann Clin Biochem 50(1):25–30. doi:10.1258/acb.2012.012096

Lillis J, Luoma JB, Levin ME, Hayes SC (2010) Measuring weight self-stigma: the weight self-stigma questionnaire. Obesity 18(5):971–976. doi:10.1038/oby.2009.353

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD (1996) A 12-Item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 34(3):220–223

Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Mousavi SJ, Omidvari S (2009) The Iranian version of 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12): factor structure, internal consistency and construct validity. BMC Public Health 9:341–349. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-341

Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Bjorner JB, Brazier JE, Kaasa S, Lepleg A, Prieto L, Sullivan M (1998) Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA Project. J Clin Epidemiol 51:1171–1178. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00109-7

Montazeri A, Harirchi AM, Shariati M, Garmaroudi G, Ebadi M, Fateh A (2003) The 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1(1):66–70. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-1-66

Latner JD, Durso LE, Mond JM (2013) Health and health-related quality of life among treatment-seeking overweight and obese adults: associations with internalized weight bias. J Eat Disord 1:3. doi:10.1186/2050-2974-1-3

Puhl RM, Latner JD (2007) Stigma, obesity, and the health of the nation’s children. Psychol Bull 133:557–580. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.557

Cooper H, Friedman S, Tempalski B, Friedman R, Keem M (2005) Racial/ethnic disparities in injection drug use in large US metropolitan areas. Ann Epidemiol 15:326–334. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.10.008

Sandberg HA (2007) A matter of looks: the framing of obesity in four Swedish daily newspapers. Communications 32:447–472. doi:10.1515/commun.2007.018

Vartanian LR (2010) Disgust and perceived control in attitudes toward obese people. Int J Obes (Lond) 34:1302–1307. doi:10.1038/ijo.2010.45

Krendl AC, Macrae CN, Kelley WM, Fugelsang JA, Heatherton TF (2006) The good, the bad, and the ugly: an fMRI investigation of the functional anatomic correlates of stigma. Soc Neurosci 1:5–15. doi:10.1080/17470910600670579

Schmader T, Johns M, Forbes C (2008) An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance. Psychol Rev 115:336–356. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.336

O’Brien KS, Latner JD, Puhl RM, Vartanian LR, Giles C, Griva K, Carter A (2016) The relationship between weight stigma and eating behavior is explained by weight bias internalization and psychological distress. Appetite. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.032

Brody CM, Trotman FK (2001) Psychotherapy and counseling with older women: cross-cultural, family, and end of life issues. Springer, New York

Tajvar M, Arab M, Montazeri A (2008) Determinants of health-related quality of life in elderly in Tehran, Iran. BMC Public Health 8:323–331. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-323

Schunk M, Reitmeir P, Schipf S, Völzke H, Meisinger C, Thorand B, Kluttig A, Greiser KH, Berger K, Müller G, Ellert U, Neuhauser H, Tamayo T, Rathmann W, Holle R (2012) Health-related quality of life in subjects with and without Type 2 diabetes: pooled analysis of five population-based surveys in Germany. Diabet Med 29(5):646–653. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03465.x

Thoits PA (1986) Multiple identities: examining gender and marital status differences in distress. Am Sociol Rev 51:259–272

Bierman A (2009) Marital status as contingency for the effects of neighborhood disorder on older adults’ mental health. J Gerontol 64:425–434. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbp010

Han KT, Park EC, Kim JH, Kim SJ, Park S (2014) Is marital status associated with quality of life? Health Qual life Outcomes 12:109–119. doi:10.1186/s12955-014-0109-0

Asad AL, Kay T (2015) Toward a multidimensional understanding of culture for health interventions. Soc Sci Med 144:79–87. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.09.013

Clair M, Daniel C, Lamont M (2016) Destigmatization and health: cultural constructions and the long-term reduction of stigma. Soc Sci Med. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.021

Acknowledgments

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The work has been performed according to ethical standards of the national ethics committee.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all of the participants before participation in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Farhangi, M.A., Emam-Alizadeh, M., Hamedi, F. et al. Weight self-stigma and its association with quality of life and psychological distress among overweight and obese women. Eat Weight Disord 22, 451–456 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0288-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0288-2