Abstract

Purpose

The main aim of this clinical study was to explore how adolescent patients with eating disorders and their parents report their perceived self-image, using Structural Analysis of Social Behavior (SASB), before and after treatment at an intensive outpatient program. Another aim was to relate the self-image of the young patients to the outcome measures body mass index (BMI) and Children’s Global Assessment Scale (C-GAS) score.

Methods

A total of 93 individuals (32 adolescents, 34 mothers, and 27 fathers) completed the SASB self-report questionnaire before and after family-based treatment combined with an individual approach at a child and youth psychiatry day care unit. The patients were also assessed using the C-GAS, and their BMI was calculated.

Results

The self-image (SASB) of the adolescent patients was negative before treatment and changed to positive after treatment, especially regarding the clusters self-love (higher) and self-blame (lower). A positive correlation between change in self-love and in C-GAS score was found, which rose significantly. Increased self-love was an important factor, explaining a variance of 26 %. BMI also increased significantly, but without any correlation to change in SASB. The patients’ fathers exhibited low on the cluster self-protection. Mothers’ profiles were in line with a non-clinical group.

Conclusions

Results indicate that the self-image of adolescent patients change from negative to positive alongside with a mainly positive outcome of the ED after treatment. Low self-protection according to SASB among fathers suggests the need for greater focus on their involvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) are complex, multi-faceted and severe psychosomatic conditions with significant mortality. They lead to great suffering for the young patients and stress for the family and social network. EDs are often associated with considerable treatment problems. Moreover, patients with anorexia nervosa and those with bulimia nervosa have greater personality deviations (disorders) and psychiatric comorbidity compared to a normal population, primarily depression, anxiety and compulsive symptoms [1, 2]. Therefore, it is of great importance to examine EDs from all possible aspects.

Different aspects of self-evaluation in EDs have been studied: Bardone-Cone and colleagues [3] suggest that an improved self-concept may be an integral part of a full ED recovery. They report that the self-concept, in terms of self-esteem and self-directedness, of fully recovered patients with an ED is comparable to the self-concept of controls, whereas partially recovered individuals are more similar to patients with an active ED. Hartmann et al. [4] found a primarily submissive and non-assertive interpersonal style among ED patients. Patients with anorexia nervosa changed most with respect to submissiveness, which can be expressed as putting the needs of others before one’s own to secure relationships. This interpersonal strategy, when unsuccessful, can be shifted into taking control over the body and the body weight. The treatment program with a strong focus on relationships changed the interpersonal patterns of the patients significantly, a change considered positive. In a very wide sample of adolescents aged 15–19 years, Curzio et al. [5] found correspondence between AN and self-image measured by Offer Self-image Questionnaire (OSIQ) [6]. It evaluates psychological well-being and adjustment and comprises five different aspects: the psychological self, the social self, the family self, the sexual self and the coping self. The adolescents at risk for AN reported higher scores in impulse control and psychopathology and family relationships represented a risk factor.

Across all EDs there is dysfunction of emotion regulation [7, 8]. ED symptoms, like symptoms in many other mental disorders, could be seen as a way of adapting to emotionally overwhelming situations to restore interpersonal and intrapsychic balance, but in a maladaptive form [9]. Patients with an ED make efforts to function, working hard to leave themselves, avoiding the authentic experience of their bodies, thoughts and feelings according to Cook-Cottone [10], the ED symptoms allowing them a sense of an embodied self, of which they are in control, but employing them in a pathological engagement with their bodies.

It has been known for a long time that patients with different EDs have a negative self-image [11, 12]. Often a personal loss or an emotionally stressful situation precedes the start of an ED [13] in a sensitive adolescent. Individual vulnerability of genetic origin [14] together with a negative self-image formed and preserved interactionally [15] may be one of the prerequisites for an ED.

According to interpersonal theory [16, 17], the self-image is formed in close relationships with significant others in early life and has influence on how the person percepts, acts and reacts in future interactions with others. It also has an impact on how others respond to him and her. For example, a person with a negative self-image tends to behave (outside of conscious awareness) in ways that shape the response from others. By this social behavior the negative self-image becomes confirmed and preserved [9]. Based on Sullivan’s interpersonal theory, Benjamin developed The Structural Analysis of Social Behavior (SASB) questionnaire [17–19], built on two axes, interdependence/autonomy (self-control vs self-emancipation) and affiliation (self-love vs self-hate), forming a circumplex pattern with eight distinct clusters. SASB can be measured in three different aspects (surfaces) with a specific interpersonal focus: other (1st), self (2nd), self-image (3rd). The third surface reflects internalized actions towards oneself (introjection), forming the self-image of the person. Self-affirmation, self-love and self-protection characterize a positive self-image and self-blame, self-attack and self-neglect characterize a negative self-image, predominantly self-love and self-attack, respectively.

SASB has been used in connection to different psychic conditions [20]. Humphrey [21] studied 74 family triads with a daughter (mean age of 18) suffering from ED, with respect to the image of self and others, as measured by the Structural Analysis of Social Behavior (SASB) questionnaire. The patients with anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa (or mixed), all had a negative self-image and showed serious deficits in self-care and extreme self-destructiveness compared to normal controls, but their parents did not. Thus there is strong evidence of a negative self-image across different eating disorders.

Since the mid-1990s there is a quality control database, an internet-based collection system for specialized ED-treatment units in Sweden. It has developed from the Coordinated Evaluation and Research at Specialized Units for Eating Disorders (CO-RED) project into Stepwise [22] today. The cluster version of the SASB questionnaire is used to measure the perceived self-image in these projects. In two studies by Björck et al. on samples from the CO-RED-project, ED patients reported significantly more negative interpersonal profiles compared to controls [23] and self-hate was the most important factor for predicting a poor outcome [24]. In another study, Birgegård et al. [25] confirmed bulimic self-hate as a moderate, and anorexic self-control as a powerful, predictor of outcome. Forsén Mantilla et al. has studied self-image and eating disorder symptoms using Stepwise in adolescents [26] and have found that self-image was important for ED symptoms in both sexes but three times stronger for girls in the normal sample, while associations between self-image aspects and ED in the clinical sample were much stronger than in the normal sample, self-love and self-blame being most important for boys and self-affirmation and self-blame for girls. In another study by Mantilla and Birgegård, also using Stepwise, the association between self-image and eating disorders symptoms in healthy and in non-help-seeking clinical young women [27] in two different age groups: 16–18 years and 19–25 years. Low self-love and high self-blame were associated with ED symptoms in all groups except in older BN-patients.

Childhood adversities and problems in family functioning have been widely reported in families with an ED [28]. Negative maternal messages regarding their daughters’ eating and weight are associated with maladaptive exercise and ED [29]. Holtom-Viesel and Allan found in a recent systemic review that families across all eating disorder diagnoses reported more problems in family functioning than controls [30]. Patients with an ED who had more positive perceptions of family functioning, generally had more positive outcomes irrespective of severity of the ED. In light of this it seems important to get to know the parents’ self-image. Hitherto, studies on self-image, using the SASB questionnaire, seem to have been done mainly in adult ED patients, but rarely in young patients together with their parents. Also, self-image have rarely been assessed before and after treatment, and related to outcome. We also wanted to find out if the treatment had an impact on the self-image of the adolescents and of their parents and if there was a correlation to the amelioration of the patients’ ED.

Aims

The main aim of this clinical study was to explore the self-image, using the SASB questionnaire, of adolescent patients with ED diagnosis and their parents before and after treatment of a duration of 1.3 ± 0.2 (mean ± standard error of mean [SEM]) years at an intensive outpatient program within a clinic for child and youth psychiatry. Another aim was to relate the self-image of the patients to the outcome measures body mass index (BMI) [31] and Children’s Global Assessment Scale (C-GAS) [32] score before and after treatment.

The following specific questions were addressed:

-

1.

What was the characteristic feature of the self-image reported by adolescent patients with an ED, using the SASB, before and after treatment?

-

2.

What was the characteristic feature of the self-image reported by the parents of adolescent patients, using the SASB, before and after treatment?

-

3.

Was there a correlation between changes in SASB clusters and outcome measured by the C-GAS and BMI among the adolescent patients?

Materials and methods

Setting of the study and context of the treatment

The setting of the study was a specialized day care unit for young patients with EDs and their parents in a medium-sized town in mid-Sweden. The patients were initially referred from the five outpatient wards, which also belong to the Department of Child and Youth Psychiatry in the region.

The intensive outpatient program was family-based with an individual approach. It had an interpersonal focus, and it was not manualized. The treatment started with the patients having meals at the day care unit during weekdays together with the staff. The parents were encouraged to establish the same scheme at home and to support their children during meals. At the beginning, emphasis was put on reestablishing good eating habits and full nutrition. In some cases, the patients needed inpatient care for some time because of very low weight or because of total refusal to eat. To ensure that the time as an inpatient was kept as short as possible, there was close collaboration between the two staff teams. Family treatment sessions were held regularly. At the beginning, they were more directive, to help with practical things. When these efforts started to work, more attention was directed to relations within the family. Two staff members (treatment assistants) and one therapist (a psychologist or a social worker) were assigned to the family and continued to support the family until the end of treatment. The professionals worked hard to engage with the patient and her/his parents, using the initial measurements as point of departure for the treatment, and encouraging the patient and her/his parents to identify and express their feelings. Regular medical checks were conducted.

Study design

The study has an observational cohort design. We used “research-quality naturalistic data” (Birgegård [22]) based on a clinical sample of ED adolescent patients and their parents. They received treatment in the outpatient program between May 2004 and May 2010. A few patients were admitted in the beginning of the period, when the unit, which was quite small, was set up.

Participants

We asked all adolescent patients and their mothers and fathers, who started treatment, to answer the self-report questionnaire, both before and after the treatment. From the beginning this was a quality control database study.

Then we decided to make a research study and got ethical approval. Some patients/parents did not want to participate in both studies.

The final sample included 32 patients (3 boys and 29 girls) between 12 and 17 years, mean age 15.6 ± 0.7 years (mean ± SEM), at admission. The distribution of ED-diagnoses: anorexia nervosa AN (n = 19; 59 %), EDs not otherwise specified (EDNOS) of anorectic type (EDNOS-AN) (n = 13; 41 %). Altogether 61 parents were part of the final sample, 34 mothers and 27 fathers, of which 28 mothers and 23 fathers had participating children. The majority of the parents lived together. Eight mothers and four fathers in the study lived separately from the other parent. All included were biological parents. Three patients did not have a participating parent in the study, seven had either of the two and 22 had both parents.

Measures

Structural Analysis of Social Behavior (SASB) [17–19] was used to assess perceived self-image. It comprises 36 self-referential statements, framed either positively or negatively. Items are rated on a scale of 0 (not at all characteristic) to 100 (perfectly characteristic) in 10-point increments, indicating the degree to which each behavior applies. Responses below 40 represent a disagreement with the statement, whereas responses of 40 or above represent agreement. The items can be formed into a circumplex pattern containing eight distinct clusters of self-image: (1) self-emancipation; (2) self-affirmation; (3) self-love; (4) self-protection; (5) self-control; (6) self-blame; (7) self-hate; and (8) self-neglect. The cluster scores are obtained by dividing the sum of the items comprising the cluster by the number of items in the cluster. Numbers 2, 3, and 4 are positive clusters, whereas 6, 7, and 8 constitute negative clusters (Fig. 1). The independence/dependence variable is formed by clusters 1 and 5. The reliability of the SASB questionnaire is supported by empirical studies, with an alpha of 0.74 [19, 33]. The internal consistency has been reported to be 0.76 [19] and for the Swedish version, Cronbach’s alpha is around 0.80 [34]. Factor analysis has yielded structures confirming the underlying SASB cluster model [17, 19].

From: Benjamin, LS (1996) Interpersonal diagnosis of treatment and personality disorders, 2nd Ed. N.Y.: The Guildford Press [6] © The Guildford Press. Modified by Mantilla and Birgegård Journal of Eating Disorders 2015 3:30 [27]

The SASB Introject cluster model. The model displays the eight clusters and the two axes (Affiliation and Autonomy)

The Children’s Global Assessment Scale (C-GAS) [32]. The C-GAS is a measure based on clinical assessment of global functioning of patients aged 4–20 years. The scale is continuous, ranging from 0 to 100, where 100 = very good functioning in every aspect. Concurrent validity is documented for C-GAS [35], but “since no other ‘gold standard’ for global assessment of functioning exists, face validity seems to be of more value than concurrent validity” [36].

Body mass index (BMI) This measure is defined as the person’s weight in kilograms, divided by the square of the person’s height in meters. Values are categorized using World Health Organization cut-off points: normal, overweight +1 SD, obesity +2 SD, thinness −2 SD, severe thinness−3 SD [31]. Normal BMI values increase with the age of healthy children. Normal values for boys are a little lower (compared to girls) under 16 years and a little higher after 16 years of age. For example at 15.6 years the normal range (±1SD) for girls is 18.0–23.8 and for boys 18.0–23.1. Weight and height are also shown separately.

Procedure

Administration of the SASB questionnaires and the BMI measurements took place on the first day of treatment at the unit. The C-GAS was performed within the first 2 weeks of the treatment and at the end. The physical examination including weight was performed after the questionnaires were completed. At the second last meeting before ending of the treatment, the measures were administered again. Both the patients and their parents completed the SASB questionnaire on these occasions. The results were presented to the family at the last consultation. The patients were diagnosed in the beginning and at the end of the treatment by using DSM-IV-TR [37] by a child and youth psychiatrist.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed in JMP® version 10.0.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). We tested the distribution of data using Shapiro–Wilk statistics and quantile plots for normality. We also studied bivariate scatterplots between change (before and after treatment) of SASB clusters and change of C-GAS as well as of BMI. When there was normal distribution, we used one-way analysis of variance to compare means. In the case of non-normal distribution we used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test [38], namely in the following variables: SASB 4, 6, 7, after children; SASB 6, 7 before and 5, 6, 7 after mothers; SASB 6, 7 before and 4, 6, 7 after fathers. Standard error of means (SEM) estimates the standard deviation of the distribution of mean estimators. We performed pairwise correlation using the Pearson product–moment method (r), if normality (parametric method), and if not Spearman rho (non-parametric method). The level of significance was set at fixed levels to 0.05, 0.01, 0.001.

In one case we found a strong linear relationship (change in C-GAS vs change in cluster 3), and we used least square regression to fit data obviously following a line. We used analysis of variance and F test. These variables were normally distributed.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Central Research Ethicals Vetting Board in Stockholm, Sweden (Dnr Ö 16-2010). All young patients and their parents signed an informed consent to participate. The parents signed on behalf of their underage children. We gave assurance that refusal to participate in the study would not compromise the patients’ treatment in any way. No incentives were given.

Results

Adolescent patients’ self-image before and after treatment

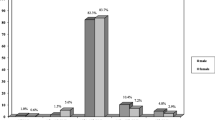

Before the treatment (Table 1; Fig. 2) the values for the positive SASB clusters 2–4 were lower for the adolescents compared to a normal group [34], clusters 2 (self-affirmation) and 3 (self-love) being the lowest (p < 0.05). Significantly increased values for the negative SASB clusters were found in cluster 6 (self-blame) (p < 0.01) and cluster 7 (self-hate) (p < 0.05). After treatment (Table 1) the values for the mentioned clusters changed significantly, cluster 2 (p < 0.001), cluster 3 (p < 0.001) and cluster 6 (p < 0.001) the most. The initial negative self-image of the patients had turned positive.

Structural analysis of social behavior (SASB) clusters 1–8 and adolescent patients’ mean SASB profile before and after treatment. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Normal group, see Ref. [34]

Parents’ self-image before and after treatment

The self-image of the mothers was positive as a whole, both before and after treatment (Table 1). The self-image of the fathers had a distinctive pattern, with a significantly low value only for cluster 4 (self-protection) (p < 0.001) compared to a normal group. It remained the same after treatment (Table 1; Fig. 3).

Structural analysis of social behavior (SASB) clusters 1–8 and fathers’ mean SASB profile before and after treatment compared to a normal group [34] ***p < 0.001

Outcome measures: C-GAS and BMI

The patients had significant positive changes in C-GAS, weight, and BMI. Height increased by 1 cm on average (Table 2). After the treatment 24 persons had no ED diagnosis, 3 had AN and 5 EDNOS.

Relationship between change of the adolescent patients’ self-image and outcome measures (change of C-GAS and BMI)

The bivariate plots of change of C-GAS and SASB 1–8 (cluster 1–8) were examined and normal confidence ellipse (p = 0.95) as well as correlations were constructed. Only three clusters had significant correlations, i.e., cluster 2 (r = 0.42; p < 0.05), cluster 3 (r = 0.55: p < 0.001) and cluster 8 (r = −0.50: p < 0.01).

The change of cluster 3 versus the change of C-GAS showed an obvious linear relationship in the plot. Therefore, a linear regression analysis was conducted between these variables. The linear model was significant as well as the estimated parameters (F = 10.3 DF = 1, n = 31, R 2 = 0.26). The conclusion is therefore: the higher the increase in self-love, the better the functioning of the patient post-treatment.

No relationship was found between change of different SASB clusters and change of BMI.

Discussion

The main aim of the present study was to explore how adolescent patients with ED diagnosis and their parents report their self-image, using SASB, before and after treatment at an intensive outpatient program. Another aim was to relate the self-image of the young patients to the outcome measures BMI and C-GAS score before and after treatment. The patients as a group gained weight and improved their social functioning (as shown by an increase in C-GAS scores), and a majority (75 %) did not have an ED diagnosis at the end of the treatment. The patients’ self-image changed from negative to positive: low values for positive clusters increased and high values for negative clusters decreased. The C-GAS scores correlated positively and linearly to SASB cluster 3 (self-love), indicating that the greater the increase in self-love, the better the social functioning. There was also a positive correlation between C-GAS and SASB cluster 2 (self-affirmation) and a negative correlation to SASB cluster 8 (self-neglect), which underlines the importance of a more positive self-image to the patient. No relationship was found between change of different SASB clusters and change of BMI.

Negative self-image, measured by the SASB questionnaire, among ED patients is consistent with findings in previous studies by Humphrey [21], Björck et al. [23] for adults and by Forsén Mantilla, Bergsten and Birgegård [26] for adolescents. In this study, we also show that the self-image can be changed after treatment.

Increased self-love seems to be the most important outcome factor in our study. Björck et al. [24] found that high self-hate initially predicted in part a poor outcome in adult patients with different categories of EDs. In a study by Birgegård et al. [25] on adult patients, mainly self-control, but also self-neglect and self-protection predicted outcome in anorexia nervosa. Self-hate/self-love moderately predicted outcome in bulimia nervosa. In our study, the more the patients moved on the dimension of affiliation (Fig. 1) towards positive by increasing self-love, the better the outcome measured by C-GAS, and this could underline the importance of self-hate initially for a worse prognosis in those studies. Although the EDs of the young patients in the present study were predominantly restrictive, self-control did not stand out as an important cluster. No significant elevation, or change, in self-control was noted. This is in line with Forsén Mantilla et al. [26] on adolescents. It is possible that a cluster on the axis of autonomy (Fig. 1) like self-control is more important for adult patients. Initial self-blame and self-affirmation for girls and self-love and self-blame for boys predicted ED symptoms in the study by Forsén Mantilla. The importance of these clusters corresponds well with our findings.

The self-image of the patients turned from negative to positive after treatment. According to interpersonal theory [17], children tend to handle parents’ unpredictable and hard-to-understand actions by blaming themselves. Adolescents still living in the parent family home are dependent on support and on open communication—and at the same time they are struggling to individuate. This gives the parents an important role to play, not in the least if the child has an ED. There are indications that family-based therapy can be helpful in the treatment of adolescent patients [39]. Family therapy might have been an important intervention, for the parents to be able to approach the ED symptoms of their children, and to deepen their mutual understanding and relationship. In the individual interaction between the patient and the staff there has been a focus on validating communication and on identifying and expressing feelings, probably leading to improved skills in emotion regulation and less ED symptoms [15]. A positive self-image and less ED symptoms could in terms of Cook-Cottone reflect a positive body-image together with awareness of internal needs and resources and of external demands and support and a growing self-care with loving-kindness (attunement) [10]. Self-love accounts for 26 % of the variance in change of C-GAS in this study, which suggests the importance of this SASB cluster to young ED patients, who tend to isolate themselves and to be preoccupied with negative thoughts and actions to themselves. There was a significant increase in the young patients’ BMI, but no correlation to any of the changes in different SASB clusters, which suggests that weight gain is not related to a specific SASB cluster. The lack of correlation between the two measures may be due to the complexity of eating disorders, where patients for example can have different patterns of recovery: changes in psychic health come earlier or later in connection to the physical recovery. In part there could also be a statistical explanation. Every cluster is built on a lot of variables, handled with factor analysis, and any correlation to BMI could be disguised.

The self-image of mothers was overall positive, which was in line with a study by Humphrey [21]. Fathers scored low on self-protection, with possible implications for nurturing and protection of others as well as themselves. The self-image of the fathers in our study may have informed the marital as well as the father–child relationships. The importance of malfunctioning of the latter in patients with ED has been shown in different ways [21, 40–42]. Self-image is closely connected to attachment [43], which we also have investigated in this sample and will be reported in a forthcoming article.

Methodological considerations

The sample of the study was small, which may limit the generalization of our findings. The patients were not stratified into different groups according to gender or to ED-diagnoses because of the small sample. Stratification may be less important in a study of young patients who often cross over to another ED category [7, 44] and a negative self-image is prevalent in all categories and in both genders [7, 21, 23, 26]. In this clinical study, we used values from a normal group [34] for control. The values of this normal group are mainly in the same range as the ones Forsén Mantilla et al. [26] found in a non-clinical group of female adolescents except for cluster 1 (higher). ED-specific outcome measures would have been appropriate in the study and they were also used, but as a member of the internet-based collection system for specialized ED-treatment units in Sweden we had to change instruments during the project. Having examined the fall-off, we found that the differences were small both in the distribution of diagnoses and of self-image.

Conclusions and clinical implications

Our study confirms a negative self-image according to SASB among adolescent ED patients. The self-image changed to positive after treatment. Increasing self-love seems to be very important and appears to be connected to better functioning. The self-image of the mothers was positive and did not change. The fathers in our study displayed low self-protection, which remained unaffected, indicating, either that family therapy is not enough, or that the focus on the father–child relationship needs more emphasis.

Since we did not use prospective data, it is not possible to know if the role of self-image of the ED patients and their parents was causal or consequential. Therefore, a prospective controlled study on a larger scale would be of great interest. Another proposal for research is to do more follow-ups of these patients in a longitudinal study.

For clinical implications it seems important for treatment and preventive measures to include a focus on self-image in a family context. Professionals and parents will become more observant on the risk of confirming the negative self-image of the patient in their mutual interaction, counteract it and give validation of the patient´s feelings. The patient will get good relational experiences, which promote positive self-treatment, and will learn new more beneficial patterns for social behavior. The need for maladaptive strategies of emotion regulation, like ED symptoms, may diminish. Fathers can be alerted of their tendency to give low care to themselves and to others and be encouraged to engage more in their own emotional needs as well as their family’s. Moreover, actively engaging fathers in the treatment would ensure greater support to mothers and children. Repeated measurements of self-love, using SASB, during treatment could help to assess the effect of the treatment.

References

Råstam M (1992) Anorexia nervosa in 51 Swedish adolescents: premorbid problems and comorbidity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31(5):819–829. doi:10.1097/00004583-199209000-00007

Braun DL, Sunday SR, Halmi KA (1994) Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with eating disorders. Psychol Med 24(4):859–867. doi:10.1017/S0033291700028956

Bardone-Cone AM, Schaefer LM, Maldonado CR, Fitzimmons EE, Harney MB, Lawson MA, Robinson DP, Tosh A, Smith R (2010) Aspects of self-concept and eating disorder recovery: what does the sense of self look like when an individual recovers from an eating disorder? J Soc Clin Psychol 29(7):821–846. doi:10.1521/jscp2010297821

Hartmann A, Zeeck A, Barrett MS (2009) Interpersonal problems in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 43(7):619–627. doi:10.1002/eat20747

Curzio O, Bastiani L, Scalese M, Cutrupi V, Romano E, Denoth F, Maestro S, Muratori F, Molinaro S (2015) Developing anorexia nervosa in adolescence: the role of self-image as a risk factor in a prevalence study. Adv Eat Dis 3(1):63–75. doi:10.1080/21662630.2014.965721

Offer D, Howard KI (1972) An Empirical Analysis of the offer-self-image questionnaire for adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 27(4):529–533. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750280091015

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R (2003) Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther 41(5):509–528. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00088-8

Brockmeyer T, Skunde M, Wu M, Bresslein E, Rudofsky G, Herzog W, Friederich H (2014) Diffficulties in emotion regulation across spectrum of eating disorders. Compr Psychiatry 55(3):565–571. doi:10.1016/coppsych.2013.12.001

Benjamin LS (1993) Every psychopathology is a gift of love. Psychother Res 3(1):1–24. doi:10.1080/10503309312331333629

Cook-Cottone CP (2015) Incorporating positive body image into the treatment of eating disorders: a model for attunement and mindful self-care. Body Image 14:158–167. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.03.004

Bruch H (1973) Eating disorders, obesity, anorexia nervosa and the person within. Basic Books, New York

Strauss J, Ryan RM (1987) Autonomy disturbances in subtypes of anorexia nervosa. J Abnorm Psychol 96(3):254–258. doi:10.1037/0021-843X963254

Sassaroli S, Ruggiero GM (2005) The role of stress in the association between low self-esteem, perfectionism, and worry and eating disorders. Eur Eat Dis Rev 37(2):135–141. doi:10.1002/eat.20079

Thornton LM, Mazzeo SE, Bulik CM (2011) The heritability of eating disorders: methods and current findings. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 6:141–156. doi:10.1007/7854201091

Monell E, Hogdahl L, Mantilla EF, Birgegard A (2015) Emotion dysregulation, self-image and eating disorder symptoms in university women. J Eat Disord 3:44. doi:10.1186/s40337-015-0083-x

Sullivan HS (1953) The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. Norton, New York

Benjamin LS (1974) Structural analysis of social behavior. Psychol Rev 81(5):392–425. doi:10.1002/9781118001868ch20

Benjamin LS (1996) Interpersonal diagnosis and treatment of personality disorders, 2nd edn. The Guildford, New York

Benjamin LS (2000) SASB Intrex user’s manual. University of Utah, Salt Lake City

Granberg Å, Armelius K (2003) Change of self-image in patients with neurotic, borderline and psychotic disturbances. 10(4), 228–237 10.1002/cpp.371

Humphrey LL (1988) Relationships within subtypes of anorectic, bulimic and normal families. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27(5):544–551. doi:10.1097/00004583-198809000-00005

Birgegård A, Björck C, Clinton D (2010) Quality assurance of specialized treatment of eating disorders using large-scale internet-based collection systems: methods, results and lessons learned from designing the stepwise database. Eur Eat Dis Rev 18:251–259. doi:10.1002/erv.1003

Björck C, Clinton D, Sohlberg S, Hällström T, Norring C (2003) Interpersonal profiles in eating disorders: ratings of SASB self-image. Psychol Psychother Theor, Res Pract 76(4):337–349. doi:10.1348/147608303770584719

Björck C, Clinton D, Sohlberg S, Norring C (2007) Negative self-image and outcome in eating disorders: results at a 3-year follow-up. Eat Behav 8(3):398–406. doi:10.1016/jeatbeh200612002

Birgegård A, Björck C, Norring C, Sohlberg S, Clinton D (2009) Anorexic self-control and bulimic self-hate: differential outcome prediction from initial self-image. Int J Eat Disord 42(6):522–530. doi:10.1002/eat20642

Forsén Mantilla E, Bergsten K, Birgegård A (2014) Self-image and eating disorder symptoms in normal and clinical adolescents. Eat Behav 15:125–131. doi:10.1016/jeatbeh201311008

Mantilla EF, Birgegård A (2015) The enemy within: the association between self-image and eating disorder symptoms in healthy, non help-seeking and clinical young women. J Eat Dis 3:30. doi:10.1186/s40337-015-0067

Johnson G, Cohen P, Kasen S, Brook JS (2002) Childhood adversities associated with risk for eating disorders or weight problems. Am J Psychiatry 159:394–400. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.741

Lease HJ, Doley JR, Bond MJ (2015) My mother told me: the roles of maternal messages, body image, and disordered eating in maladaptive exercise. Eat Weight Disord. doi:10.1007/s40519-015-0238-4

Holtom-Viesel A, Allan S (2014) A systemic review of the literature on family functioning across all eating disorder diagnoses in comparison to control families. Clin Psychol Rev 34(1):29–43. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.10.005

World Health Organization (2007) The WHO child growth standards. http://www.who.int/childgrowth/en/. Accessed 6 April 2016

Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S (1985) A children’s global assessment scale (CGAS) (for children 4 to 16 years of age). Psychopharmacol Bull 21(4):747–748 Swedish translation by Helgesson M, Gustafsson P 2001–04–06

Lorr M, Strack S (1999) A study of benjamin’s eight-facet structural analysis of social behavior (SASB) model. J Clin Psychol 55:207–215

Armelius K (2001) Reliabilitet och validitet för den svenska versionen av SASB–självbildstest. Institutionen för Psykologi Umeå: Umeå Universitet

Bird HR, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, Ribera JC (1987) Further measures of the psychometric properties of the Children’s Global Assessment Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry 44(9):821–824. doi:10.1001/archpsyc198701800210069011

Schorre BEH, Vandvik IH (2004) Global assessment of psychosocial functioning in child and adolescent psychiatry. Eur Child Adol Psychiatr 13(5):273–286. doi:10.1007/s00787-004-0390-2

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision (DSM-IV-TR), 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington

Wilcoxon F (1945) Individual comparison by ranking methods. Biom Bull 1(6):80–83. doi:10.2307/3001968

Stiles-Shields C, Rienecke Hoste R, Doyle PM, Le Grange D (2012) A review of family-based treatment for adolescents with eating disorders. Rev Recent Clin Trials 7(2):133–140. doi:10.2174/157488712800100242

Gale CJ, Cluett ER, Laver-Bradbury C (2013) A review of the father–child relationship in the development and maintenance of adolescent anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs 36(1–2):48–69. doi:10.3109/014608622013779764

Perkins PS, Slane JD, Klump KL (2013) Personality clusters and family relationships in women with disordered eating symptoms. Eat Behav 14(3):299–308. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.05.007

Mountford V, Corstorphine E, Tomlinson S, Waller G (2007) Development of a measure to assess invalidating childhood environments in the eating disorders. Eat Behav 8(1):48–58. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.01.003

Zachrisson HD, Skårderud F (1010) Feelings of insecurity: review of attachment and eating disorders. Eur Eat Dis Rev 18:97–106. doi:10.1002/erv999

Milos G, Spindler A, Schnyder U, Fairburn CG (2005) Instability of eating disorder diagnoses: prospective study. Br J Psych 187(6):573–578. doi:10.1192/bjp.187.6.573

Acknowledgments

This study received financial support from the Department of Child and Youth Psychiatry, Falun Central Hospital, Falun; the Center for Clinical Research Dalarna, Falun; the Olaison Fund; and the Department of Psychology, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in our study, Adolescent patients with an Eating Disorder and their parent: A study on self-image and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gezelius, C., Wahlund, B., Carlsson, L. et al. Adolescent patients with eating disorders and their parents: a study of self-image and outcome at an intensive outpatient program. Eat Weight Disord 21, 607–616 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0286-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0286-4