Purpose

Abstract

The incidence and prevalence of eating disorders (ED) is low in general practice (GP) settings. Studies in secondary care suggest that the general practitioner has an important role to play in the early detection of patients with EDs. The aim of this study was to describe the effect (clinical outcomes and care trajectory) of screening for EDs among patients in general practice settings.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted on Medline, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Embase and WOS. The studies included were to have been carried out in a primary care setting, with screening explicitly performed in GP practices and follow-up information.

Results

Ten studies met the inclusion criteria. For all ED patients, there was an increase in the frequency of consultations in GP setting, referrals to psychiatric resources and drug prescriptions such as antidepressants, following screening procedures. Clinical outcomes remained unclear and heterogeneous. One study focused on the course and outcome of ED patients identified by screening in the GP setting and reported recovery for anorexia nervosa (AN) and BN in more than half of the cases, after 4.8 years of mean follow-up. In this study, early age at detection predicted better recovery.

Conclusion

Most of the literature on the role of the GP in screening for and managing EDs consists of opinion papers and original studies designed in a secondary care perspective. The impact of systematically screening for EDs in a primary care setting is not clarified and requires further investigation in collaborative cohort studies with a patient-centered approach, and outcomes focused on symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to DSM-IV-TR criteria, eating disorders (ED) are divided into three diagnostic categories: anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN) and eating disorders not otherwise specified (EDNOS) [1]. In the general population, EDs are relatively frequent. The incidence rate of AN is between 109 and 270 per 100,000 person-years among adolescents and young adults in the two most recent studies [2, 3], and between 200 and 300 per 100,000 person-years for BN [4]. The prevalence rates for AN in women aged 11–65 years in non-clinical populations range from 0 to 2.2 % [5, 6] and 1 % for BN in young females [7]. Complete diagnoses are rare in the general population; partial syndromes are more frequent. Around 10 % of 15- to 17-year-old females and 1.4 % of males in the general population suffer from a partial AN syndrome and are still underweight in their mid-20s [8, 9].

The consequences of EDs are severe. AN shows the highest mortality rates of all psychiatric disorders [10], with standardized mortality ratios varying across studies between 10.6 after 10 years [11] and 5.86 after a mean follow-up of 14.2 years [12]. BN is also associated with an increased mortality rate [13], nearly three times higher in patients with BN compared to controls [14]. Both disorders are associated with increased rates of suicidality [12, 13, 15, 16], and psychiatric [17, 18] and somatic comorbidities [19, 20]. In addition, these disorders are associated with social impairment [21–23]. These partial syndromes seem also to have a somatic and psychological impact in adulthood [6–9, 24].

It is usually claimed that early detection and treatment lead to a better outcome [25–27]. It is also recommended that “people with ED seeking help should be assessed and receive treatment at the earliest opportunity” (NICE 2004, quick reference guide; page 6). In line with this idea, primary care is often quoted as the most important setting for early detection [28].

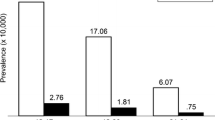

The general practitioner (GP) could be an important health-care player in the early detection and management of EDs [29]. Furthermore it has been established that ED patients consult more frequently than controls over the 5 years prior to the diagnosis [30]. GPs often underdetect EDs: less than one in ten cases of BN or binge-eating disorder (BED) and less than 50 % of cases of AN and subclinical AN are detected [2, 6]. The incidence rates for EDs diagnosed in primary care studies were as much as 20 times lower than in studies in the general population in the UK and the Netherlands, between 4.2 and 7.7 per 100 000 person-years for AN and 6.1 to 12.2 per 100 000 person-years for BN, respectively [31].

There is obviously inadequate diagnosis of EDs in primary care. We wondered if there was evidence-based data on the impact of systematic detection of EDs using a screening method in primary care settings, as the international literature often hypothesizes that since GPs are in contact with patients at an early stage of their illness, they need to diagnose them as soon as possible for early treatment to improve the outcome [25]. The aim of this paper was to review the results of the studies exploring EDs in primary care in terms of outcomes and clinical trajectory, and to investigate how they addressed the question of the effect of systematically screening for EDs among patients in a general practice setting.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Research articles were systematically sought in the Medline, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Embase and Web of Science bibliographic databases from their inception until August 2015. For instance, the search terms used on Pubmed were as follows:

(“Bulimia” [MAJR] OR “Anorexia Nervosa” [MAJR] OR “Eating Disorders” [MAJR]) AND (“Primary Health Care” [MeSH Terms] OR “Family Practice” [MeSH Terms] OR “General Practice” [MAJR]).The Cochrane Library databases and French databases (PASCAL and FRANCIS) were also searched. Articles in English, French, Spanish or German language were considered. All terms and research algorithms were defined by discussion between researchers (JSC, JC, NG and CH). The extraction of data was conducted by JSC. To identify additional candidate studies, a manual search completed this review using the reference lists for each article and the review found.

Selection of articles

The selection process followed the PRISMA guidelines [32]. After excluding duplicates, each abstract and title were reviewed to ascertain its relevance. The selection process was carried out independently by two of the present authors (JSC and JC), and consensus was sought in the event of disagreement after examining the full text. The inclusion criteria comprised: original cohort study, repeated cross-sectional study, case–control study or any study including patient follow-up information, with explicit information on ED patient sampling according to DSM-IV criteria (AN, BN, EDNOS) and patients at least partially recruited in primary care. Papers were excluded if (1) eating disorders were studied in the context of metabolic disorders such as type I diabetes, mental illnesses such as psychoses, and pregnancy; (2) patients included in the studies were under 8 years old (see NICE guidelines); (3) the study was not carried out in a primary care setting; (4) the study was not an original research article, for instance opinion papers, narrative reviews and editorials. The exclusion process considered the criteria in this order. For example, if a paper was not excluded on the first criterion, it was examined according to the second and excluded if it met this exclusion criterion, and so forth.

Literature analysis and data extraction

Information regarding author, date of publication and country were extracted. The aim of our review was to study the effect of systematic ED screening by GPs among their patients, but this was often not the main objective of the studies included. Thus, we did not use the CONSORT or STROBE guidelines to assess the quality of the randomized controlled trials or the cohort studies [33]. We (JSC, NG, JC, and CH) focused on the characteristics of the population to be studied and recruited, the recruitment methods, the types of instrument used for screening, the types of ED studied, and the duration of follow-up. We then explored the clinical outcomes and care trajectories of patients with ED following screening. If these elements of the screening procedure were not explicitly described or available in any paper, we excluded it.

Results

Identification and selection of the relevant literature (Fig. 1)

After removing duplicates, 583 papers were identified. The literature search on the Cochrane library database, PASCAL and FRANCIS, did not identify any further study. One hundred and ten studies in primary care setting focusing on EDs were excluded from our review because they were not original research papers (103 using title and abstract and 7 more after full text assessment). They were mostly opinion papers, editorials or reviews. Half of them were published after 2003, mostly from the USA and northern Europe. They often suggested ways for GPs to detect EDs, or concluded the urgent need to train GPs, but without relevant information or objective data. Acceptable chance-adjusted agreement (kappa score = 75.6 %) was found between the two authors who selected the 151 papers for full text assessment. 118 were directly selected from the title and abstract by both authors, and 33 were first selected by one of the two authors and discussed in their full text version. Twenty papers among the 118 papers directly selected were secondarily excluded after full text assessment, because they met at least one exclusion criterion, and 92 papers were excluded because they did not include any follow-up information. Twenty-eight papers were excluded because they did not specify that the screening procedure was carried out in primary care. Finally, 11 papers met all the inclusion criteria and were reviewed. Two papers were reporting on the same study at two different stages. The results of the ten different studies reviewed are reported in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

The follow-up indicators found in these studies fell into two categories: care trajectories and clinical outcomes (Tables 4, 5). The care trajectory was described according to the presence or frequency of consultations in general practice and also referrals to other specialties, and medication prescribed. The clinical outcomes were measured in terms of scores based on ED symptoms and other biometric indicators. Studies describing both indicators classified from the largest to the smallest number of ED patients included were presented first in tables.

Main characteristics of the studies included (Table 1)

The ten studies (out of the 11 papers preselected) were conducted between 1989 [35] and 2012 [39]. Seven were undertaken in Europe (four in Great Britain, [35, 36, 40, 43, 44] two in the Netherlands [34, 39], one in Spain [37]), two in North America [38, 42] and one in Australia [41]. Nine studies were mainly conducted by psychiatrists and one only by GPs [37]. The most recent study involved collaboration between psychiatrists, epidemiologists and GPs [39]. 6/10 studies were observational: three studies were cohort studies, [34–36, 40] two were case–control studies [38, 39] and one was a cross-sectional study with follow-up data [37]. 4/10 were trials (one pilot study [44] and three RCTs [41–43]). The six studies targeted patients with all types of ED, whereas the trials focused on patients with BN. Only one study focused on the same topic as our review, studying the course and outcome of patients with EDs detected in primary care [34]. The aims of the studies were to describe patients with EDs in a primary care setting [35–37, 40] and the utilization of health-care services by patients with EDs [34, 38, 39]. The four trials consisted in comparing primary care interventions on bulimic patients with other interventions or placebo.

Study population, recruitment, screening and diagnosis instruments (Table 2)

The different populations were approached via GP registers or databases, general practices or community settings. In 3/10 studies, the population studied was not entirely specific to primary care practice [38, 41, 42]. One case–control study was about the Oregon health-care organization, structured into seven specialty units (general practice, mental health, addiction, gynecology, emergency, telephone consultations and inpatient care) [38]. One Australian RCT was conducted directly among patients in the community [41]. Another American RCT selected patients from primary care clinics, in which general practice and other specialties were not differentiated [42]. The population samples approached for recruitment varied from 28,016 patients [35] to 2,467,275 patients [40] with short study periods, from 1 to 5 years. The six observational studies aimed to recruit both females and males, whereas the four trials only focused on females. In two studies, participants from the age of 8 years were recruited [34, 39]. The others aimed to recruit teenagers and adults (range 10 [40] to 55 years [38]). In 7/10 studies, including two trials, GPs or health-care providers recruited patients with EDs in their practice [34, 37–40, 43, 44]. In 3/10 studies (including two trials), the recruitment of patients was performed by the researchers in the community through the media, in GP waiting rooms, or both, sometimes without asking GPs to recruit, outside consultations [35, 36, 41, 42]. GPs did not take part in the research design or the process of recruitment in these studies.

According to studies, there was huge variability in both screening and diagnosis procedures. The procedures were described in all studies. Diagnoses were not validated using the same standardized methods. When researchers sought to identify patients with EDs in the clinical sample for recruitment, they used specific screening measures, mainly self-administered questionnaires such as the Eating Attitude Test (EAT-26) for AN [35, 36], and the Bulimia Test Revised (BULIT-R) and the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire 4 questions (EDE-Q4) for BN [41]. Walsh used a brief telephone interview checklist based on DSM-IV criteria [42]. The Durand and Waller trials were based on clinical suspicion by GPs and nurses using DSM-IV criteria [43, 44]. Cases were defined in the King and Banasiak studies on the basis of high screening scores, over 20 for EAT-26 [35, 36] and over 94 for BULIT-R [41]. Specific diagnosis scores were used in the four trials by the research team [41–44], such as the EDE (full version) and the BITE questionnaire (Bulimic Investigatory Test, Edinburgh). Walsh used a validated structured clinical interview for diagnosis [42]. Patients with EDs in five studies using databases were diagnosed on the basis of the DSM III-R or DSM-IV classification [34, 37–40], implemented by GPs or health-care providers, and the ICPC1 (International Classification of Primary Care, code T06: anorexia, bulimia) was used in two studies by the same author [34, 39]. These five studies did not involve any screening instruments, as recruitment was directly conducted by the health-care providers. Cases were validated in five observational studies [34–36, 38–40] by the research team (always including a psychiatrist) when it was the GPs or health-care providers who recruited patients [34, 38–40], using DSM classification or ICPC 1. In the King cohort [35, 36], validation of diagnosis was performed using the Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS), a detailed eating interview, and the Symptom Rating Test (SRT), to classify cases in degrees of ED severity. The validation of diagnoses was not specified in the four trials, nor in the Spanish study [37]. The number of patients recruited when reported in the studies varied from 204 [40] to 748 [35, 36], recruited directly by researchers, or by GPs with validation by the research team. The DSM-IV was used as the reference classification in the studies conducted after 1996.

Description and follow-up of the patients included (Table 3)

All these studies included only a small proportion of EDs in the study population, considering the initially identified population. The total numbers of patients with EDs included vary from 11 in the pilot trial [44] to 204 in the case–control study conducted in the Oregon health-care organization [38]. The types of cases included varied: the Van Son cohort included incident cases [34], whereas the Turnbull study made a random selection of 204 patients with ED (100 with BN and 104 with AN) among prevalent cases [40]. The type of ED also varied. Four studies included patients with AN, BN and EDNOS (or partial syndromes) [35–39]; two included patients with AN and BN and did not take EDNOS into account [34, 40]. One study found no case of AN [35, 36]. The four trials included only patients with BN. There was no study on patients with AN only. Once detected, relatively few cases were confirmed and included, as a result of missing data or because researchers did not validate the diagnoses. In the most recent Van Son study, 80 were excluded because of missing or irrelevant data out of 227 recruited [34]. 69 patients out of the 748 recruited in the King study were included as cases [35, 36]. 204 women out of the 332 women recruited in the Striegel Moore study (not taking into account the 19 men) were included, while 128 were excluded because their diagnosis did not occur in 2002, the year of inclusion [38]. 63 cases of AN out of the 104 recruited by GPs were included by the researchers after validation in the Turnbull study [40]. In the Walsh study, 91 patients with BN were included out of the 227 recruited through GPs, newspapers and advertisements [42]. 68 patients with BN out of the 209 initially recruited by GPs were included in the Durand trial after validation by the research team [43]. There was also variation according to gender, whereby the six studies targeted both males and females and the four trials focused on females only. The Aguilar study did not find any cases among males [37], and Striegel Moore and Turnbull decided to exclude the very few cases of men identified with EDs [38, 40]. The Van Son study in 2012 did not specify gender [39]. There was also variation according to age. The mean age of patients included ranged from 21 years in one study [37] to 31.52 years in another [38]. Two studies calculated a mean age specific to each type of ED, reporting that BN patients were 3–4 years older than patients with AN [34, 38]. In the Durand study, there was a difference in mean age between the GP group and the specialist group, composed of psychiatrists. In this study, patients in the GP group were older than in the specialist group [43]. The duration of follow-up in the studies was available for six studies, ranging from a minimum of 1 month in the pilot trial [44] to 57.6 months (4.8 years) mean duration in a Dutch cohort study [34]. The other cohort study with follow-up information conducted by King had a follow-up of 18 months for the first analysis and 30 months for the second analysis [35, 36]. The trials had an artificial cutoff for the follow-up at 1–9 months. One was a cross-sectional study with no follow-up [37] and one study did not mention the duration of follow-up [40]. The numbers lost to follow-up were available for 2/6 observational studies [34–36], ranging from 0 % in one study to 63 % in the second analysis after 30 months for the King study. The four trials reported loss to follow-up varying from 0 % in the pilot study to 69 % in the Walsh trial after 5 months of follow-up [42].

Description of care trajectories (Table 4)

Data available in 6/10 studies on the care trajectory showed that patients with EDs, after identification in primary care, increased their health services use compared to patients without any ED. No study provided the three types of information about care trajectories (health service use, referrals, medication). 4/6 studies contained two of these three types [37–40] and 2/6 only one type [34–36]. Patients with EDs were also more often referred for psychiatric help and prescribed antidepressants [34–40]. Concerning primary care services, the use of health services was significantly higher in cases than controls, especially among older patients [38]. In the Aguilar study, the frequency of visits to the health center was four a year for 90.9 % of patients, suggesting frequent contacts with GPs [37]. Patients with BN had the most numerous face-to-face contacts with their GPs compared to patients with AN or EDNOS [39]. Health services use increased in the year after detection by screening compared to the year before, for telephone consultations and mental health visits and for all types of ED, with no differences between subgroups [38]. Patients with EDs had more annual contacts and referrals than controls having no depression and no ED (non-mental group) [39].

Referrals to secondary care were to mental health care, with 72 % for AN binging–purging subtype (ANBP) and 61 % for BN cases in a study [34]. In one study, 55 % of AN cases were confirmed by experts (36/63) and 40 % of BN cases were referred for psychiatric help [40]. But little detailed data were available in this study, where the aim was not to study the care trajectory. In BN cases and partial syndromes in one study, only one bulimic woman was referred to a psychiatrist [35, 36]. Three patients in the Aguilar cross-sectional study out of 13 were referred to mental health services [37].

Patients with all types of ED were often prescribed antidepressants in all studies with data on care trajectories, and more than the non-mental group in one study [39]. In another study, 68 % of patients with EDs were receiving antidepressants after identification, which is an increase of 18 % following identification [38]. In the Van Son study, patients with ED talked less often about their ED and more often about respiratory and gastrointestinal disturbances (and were more frequently receiving oral contraceptive pills and medication for the respiratory system, p < 0.01) [39]. 45 % of BN cases in the Turnbull study were prescribed psychotropic medication, including antidepressants, anxiolytics and sleeping pills, but the proportion of each type was not detailed [40].

Description of clinical outcomes (Table 5)

Clinical outcomes were mainly reported in terms of symptom intensity, frequency and number of bulimic episodes measured by scores (such as the Symptom Rating Scale, a 30-item questionnaire probing psychological symptoms experienced in the preceding week), and sometimes in terms of weight and BMI. For clinical recovery, the Van Son study conducted in 2010 showed differences in recovery and time to recovery in subtypes of ED [34]. This cohort study used composite criteria based on clinical data (BMI, use of laxatives, frequency of binge eating and induced vomiting, amenorrhea) and improvement as observed by the GPs. After 4.8 years of mean follow-up after identification, 57 % of all patients with AN had recovered, and 61 % of all patients with BN had recovered. The referral to mental health care had no effect on outcome, with no difference observed between the referred patients and non-referred patients. Patients with ANBP took the longest to recover, with a median time to recovery of 4.4 years, suggesting that they were more difficult to cure, even compared to patients with ANR. Concerning predictive factors for recovery, early age of detection, defined as “under 19 years old”, was the only variable identified. In the small cross-sectional study conducted in general practice by Aguilar [37], 4 patients with ED out of 13 were considered to be cured by their GPs, with no information on differences between subtypes. The size of the sample in this study, and the absence of any mention of the duration of follow-up did not enable any relevant conclusion on clinical outcomes. Moreover, clinical outcomes were not precisely defined, and there was no explanation of the phrase “evolving favorably”.

At 30 months follow-up in the King study, EAT scores were statistically lower than at baseline in partial syndromes, but not in BN [36]. Conversely, SRT scores were higher for all types of ED, meaning an increase in psychological symptoms. The Walsh trial showed a mean reduction in the BDI score in the “fluoxetine alone” group and also in the “fluoxetine with GSH (guided self-help manual) group” of 8.46 per month [42]. Although the patients had a better BITE score in the Durand trial with an improvement of eight points compared to baseline and BDI scores with six points of mean difference compared to baseline, most of them were still suffering from severe ED at the end of the trial and there was no difference between the two groups [43].

Three trials on BN showed small, but significant reductions in episodes of binge eating and vomiting after 1–9 months of follow-up, for patients receiving abbreviated treatment, guided self-help therapy, specialist treatment or fluoxetine following identification. In the Walsh RCT [42], one group of 22 patients with BN received a placebo and no guided self-help intervention, which is the closest to the natural course of patients. There was no statistical difference in the number of bulimic episodes or in depression scores after 5 months compared to baseline for either group. In the pilot trial conducted by Waller, patients receiving usual care and placebo did not improve after 5 months compared to baseline [44]. All these results should be considered with caution, because the clinical outcomes could be influenced by treatments, and in RCTs treatments are always given in the intervention group and not in a naturalistic setting.

Concerning measurements, the mean BMI for patients with ANBP and ANR in the Van Son study increased significantly [34]. The mean weights at follow-ups in the King studies were higher for BN patients and lower for the others [35, 36]. The Aguilar study reported only weight monitoring, performed in 42.9 % of consultations with the patients included, but not the results for weight [37]. One female patient died of AN [34].

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

We found few studies meeting our inclusion criteria. A large amount of the literature consisted of opinion papers on the role of the GP in the detection and management of EDs. Most of the literature on the role of the GP in screening for EDs adopted a secondary care perspective. Most of the literature on patients with EDs in primary care was made up of numerous cross-sectional studies. They were excluded from our review, because they aimed to validate detection tools, such as the EAT-40 [45] or 26 [46], the SCOFF [47], the BITE [48] or the EDE-Q [49] in a general population setting or primary care population, without any follow-up information. The impact of systematically screening for EDs in the general setting is not explored in the literature and needs to be investigated in further studies.

No study provided information on the impact of early detection in primary care in terms of efficacy, although some studies do give information about patient trajectory and outcome after detection.

Only ten studies in the international literature included follow-up information about clinical outcomes or referrals for patients identified using screening procedures by GPs. Only one recent study matched our aim of studying the effect of screening for EDs by GPs [34]. When information on the care trajectory after ED detection was available, there was an increase, whatever the ED subtype, in the frequency of consultations in general practice, for both ED and depression management, for referrals to psychiatric care and for drug prescriptions, such as antidepressants.

When clinical outcomes were available in the studies, they were heterogeneous. There was more information about BN than AN or EDNOS. The trials showed small, but significant reductions in episodes of binge eating and vomiting for people with BN for specific treatments, with a short-term evaluation, none longer than 9 months.

Methodological characteristics of the included studies that impact results

The results of the studies need to be interpreted with caution. First, the recruitment was carried out in a natural setting by GPs in only four of the ten studies [34, 37, 39, 40]. There was confusion between the community setting and the care delivered by GPs. The other six studies concerned patients upstream from GP consultations, who may never have consulted a GP for their ED. Some patients were recruited in waiting rooms directly by researchers. GPs were not always included in the process of recruitment. In addition, when GPs were involved in recruitment, patients recruited for the trials might never have been detected in their day-to-day practice. Two RCTs out of three allocated the patients to GPs who were not involved in their usual care setting [41, 42]. Finally, some studies included patients from both secondary care or specialty practices and primary care settings, leading to a mix of patients and a possible recruitment bias [37, 38].

Secondly, patients detected in the trials were systematically treated because of the study design. In a natural setting, we can suppose that some of the patients detected would not have been treated. The inclusion of patients in any study influences the decision by the general practitioner to treat or to refer to other specialists, changing the natural course after detection and thus the impact of normal screening in a general practice setting. Moreover, the Hawthorne effect does not guarantee the evaluation of the illness as in real life [50].

Thirdly, the studies involved small samples, ranging from 13 to 204, leading to a lack of power. Walsh explained in his RCT that because of the low prevalence of BN in the primary care setting, the researchers had to include patients directly from the community to ensure a sufficient number of participants for the trial [42]. The inclusion of patients with different ED syndromes such as AN, BN and ENOS in the same study could have led to different outcomes and care trajectories (proportion of purging cases, different targets for BMI, …). This low prevalence of EDs in the primary care setting could explain the absence in the literature of any recruitment of patients with AN only in primary care.

Fourthly, the clinical outcomes and care trajectories were very heterogeneous across studies. The time scale envisaged for outcomes in the selected articles was wide (1–54 months) and the indicators used were not comparable. A meta-analysis was thus impossible, as screening methods were different and samples too small. Predictive factors were identified in one recent study: early age at the time of detection was a predictive factor for better recovery from AN and BN, and the authors reported that patients with BN recovered faster than patients with AN [34]. Recovery was assessed using questionnaires sent to GPs. It could have been more sensitive to directly ask patients, or to use registry data or files. In this way, missing data, which was frequent in the registries explored by studies, would have probably been corrected.

All these arguments challenge the external and internal validity of the study results and raise the question of how to study EDs in general practice and primary care.

Validity of eating disorder definitions in general practice

The low incidence and prevalence of EDs in general practice is often explained in the literature as an underdetection of cases by GPs [51–53]. While it is generally agreed that GPs need to detect EDs at an early stage [54–56] to improve outcome and that there is an urgent need to train GPs to detect EDs [51, 52, 57, 58], evidence based on scientific data shows that GPs are rarely confronted with EDs as such. It seems that patients with EDs do consult GPs, but for other reasons than their EDs, explaining the underdetection by GPs. GPs have a holistic approach in their practices and do not only see the syndrome, since they consider their patients in a holistic perspective. Another explanation could be that GPs are in contact with patients who are at risk, but who may be different from those actually diagnosed and hospitalized in secondary care. The latter may not consult in primary care settings before their hospitalization. Some studies included in our review indeed showed an older mean age at detection among patients with AN (22.7 years in one [34] and 28.11 years in another [38]) than in secondary care, suggesting that the population in primary care is different from the hospitalized population.

This literature review raises some questions about the validity and the usefulness of diagnoses using the DSM classification in primary care.

First, in the Van Son and the Turnbull studies, some cases diagnosed by GPs were invalidated by the research teams, sometimes reaching nearly 40 % of cases [40]. The studies in which GPs recruited patients showed that researchers validated 60–80 % of cases recruited by GPs [34, 39, 40, 43]. GPs may detect patients with ED with more sensitivity than specialists, meaning that GPs may have the role of identifying suspected cases of ED and specialists of confirming them. A question is also raised in general practice or primary care about the validity of distinguishing different EDs in a prevention perspective. GPs detect symptoms to understand what they mean and how they are relevant to their patients, but defining a syndrome is not their principal task, in accordance with the holistic approach mentioned earlier [59].

Secondly, Van Son created categories to increase the validity of the improvement observed in the 2010 cohort, taking into account clinical criteria (BMI, number of binging–purging episodes, etc.) and the clinical impression of the GP [34]. This suggests that the existing classification at the time (DSM-IV) was not appropriate for follow-up in primary care, and this raises the question of finding other categorizations of EDs. Along with the DSM-V, categories such as those in the BED seem to be more appropriate to general practice. We also know that most EDs are viewed as EDNOS in secondary care, leading to a redefinition when cases are addressed by GPs [60].

Specific classifications such as the ICPC-2 could be useful tools to combine diagnostic procedures (anorexia nervosa/bulimia defined as P86) and symptoms or bio-psychosocial situations (general and unspecified domains, defined as AXX) [61].

In research, new qualitative and quantitative criteria to detect EDs should be explored in further studies. For instance, the detection of the feeling of loss of control, as recently studied, could be a way to bridge the ideological gap between the primary care perspective and the DSM 4 or 5 definitions [62].

Thirdly, some studies in our review, when information was available, found no differences for clinical outcomes between patients referred to specialists compared to patients managed by GPs. Our hypothesis is that patients with more severe conditions are addressed to specialists, such as psychiatrists, who then manage these patients. The outcomes of more severe patients may consequently be the same as those of patients with less severe conditions only managed by GPs. It would be of greater benefit, in practice, to evaluate when GPs should address patients with EDs to specialists, rather than comparing the two types of management.

Implications for clinical practice and future research

Cohort studies, like the one in the Netherlands, need to be carried out in other countries, including information from primary care databases and a follow-up of patients recruited by their GPs.

Researchers need to address the question of underdetection and to compare the characteristics of the population screened in primary care with the patients followed in the secondary care system and the mental health services. When the studies are collaborative, including psychiatrists, epidemiologists and general practitioners, data seem to be more relevant for both research and clinical perspectives [34, 39].

The data collection should focus on clinical and social outcomes, as well as referrals, frequency of consultations and drug prescriptions. The main challenges of such studies seem to be the issue of missing data and obtaining more precise inside details of GP consultations on symptoms and patients’ complaints. The International Classification of Primary Care has been described as a relevant classification for these challenges [24]. All in all, a large randomized controlled trial in the general population should be carried out to compare the clinical outcomes of patients detected in primary care by GPs with others treated “as usual”. The comparison between populations from general practice care and specialized care could then be effective.

GPs may be more useful in the detection of BN patients, since BN is more frequent than AN [4], and patients with BN have better outcomes than those with AN after follow-up. Further studies should also focus on EDNOS and BED. In France, guidelines exist only for AN, and our results suggest that guidelines on BN and even BED are needed.

While GPs are often given an important role to play, it seems necessary to study their attitudes toward this role in the management of patients with EDs. Recent British qualitative studies showed that GPs felt involved, but needed support and continuity of care, and sometimes felt helpless in patient management [63, 64]. One of the studies also showed that GPs had subjective methods of screening for EDs, sometimes without using weight [64]. The efficiency of these detection procedures should be studied. It would also be relevant to specifically study the expectations and attitudes of patients with EDs and their relatives toward GPs in their management.

Finally, a few studies included in our review hypothesized that depression and EDs are associated. Future research should focus on this association and investigate whether depression is a risk factor for eating disorders, or the reverse. One recent American study confirmed that low self-esteem in adolescents may be an important risk factor for the development of depression and eating disorders [65]. The usefulness of depression symptoms for GPs in screening for EDs at the primary care level requires study.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review focusing on the effect of screening for patients with EDs by GPs. It was carried out on five international databases and Cochrane databases, suggesting that we searched the entire literature on the topic. Another strength of the study was the collaborative work between GPs (JSC, JPL, CH) and psychiatrists (NG, BF) with a primary care perspective. Insufficient and heterogeneous data prevented us from conducting a meta-analysis and from studying the efficacy of screening. Few articles met our criteria focusing on our study theme. So the studies included were not systematically assessed with validated checklists, such as CONSORT. Nevertheless, study biases were discussed for each study on the basis of criteria inspired from these guidelines. Another limitation was also that our review did not take into account the differences in primary care settings between the USA, northern Europe and southern Europe, which may have influenced the role of detection assigned to the GPs. In the USA, primary care units can be found in hospitals, whereas in Great Britain or the Netherlands, primary care units in general practices are not attached to hospitals, leading to different patient profiles [66], thus limiting comparisons.

Conclusion

The effect of screening for ED by GPs among patients in the primary care setting is unknown. For this reason, it is also difficult to draw conclusions on outcomes or on care trajectories for ED patients in a primary care setting. In observational studies, following screening procedures, there was an increase for all types of ED in the frequency of consultations in general practice, referrals to psychiatric settings and drug prescriptions such as antidepressants. Clinical outcomes remained unclear and heterogeneous. One study focused on the course and outcome of patients identified by screening in the general practice setting and found recovery for AN and BN in 57 and 61 % of cases after 4.8 years of mean follow-up. An early age at detection predicted a better recovery in the same study. This data are not found in other studies. Patients with BN seemed more numerous and had better and faster recovery than patients with AN. Future research should include cohort studies conducted using primary care databases, with patients identified by screening by their GPs, focusing on clinical outcomes and depression.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th edition, text revision). American Psychiatric Association, Washington

Hudson J, Hiripi E (2007) The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry 61:348–358. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

Keski-Rahkonen A, Hoek H, Susser ES (2007) Epidemiology and course of anorexia nervosa in the community. Am J Psychiatry 164:1259–1265. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06081388

Keski-Rahkonen A, Hoek HW, Linna MS, Raevuori A, Sihvola E, Bulik CM, Rissanen A, Kaprio J (2009) Incidence and outcomes of bulimia nervosa: a nationwide population-based study. Psychol Med 39:823–831. doi:10.1017/S0033291708003942

Roux H, Chapelon E, Godart N (2013) Epidemiolgy of anorexia nervosa: a review. Encephale 39:85–93. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2012.06.001

Godart N, Legleye S, Huas C, Côté S, Choquet M, Falissard B, Touchtette E (2013) Epidemiology of anorexia nervosa in a French community-based sample of 39,542 adolescents. Open J Epidemiol 3:53–61. doi:10.4236/ojepi.2013.32009

Hoek HW (2006) Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 19:389–394. doi:10.1097/01.yco.0000228759.95237.78

Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Sanci L, Sawyer S (2008) Prognosis of adolescent partial syndromes of eating disorder. Br J Psychiatry 192:294–299. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.031112

Roux H, Blanchet C, Stheneur C, Chapelon E, Godart N (2013) Somatic outcome among patients hospitalised for anorexia nervosa in adolescence: disorders reported and links with global outcome. Eat Weight Disord 18:175–182. doi:10.1007/s40519-013-0030-2

Hoang U, Goldacre M, James A (2014) Mortality following hospital discharge with a diagnosis of eating disorder: National record linkage study, England, 2001-2009. Int J Eat Disord 47:507–515. doi:10.1002/eat.22249

Huas C, Caille A, Godart N, Foulon C, Pham-Scottez A, Divac S, Dechartres A, Lavoisy G, Guelfi JD, Rouillon F, Falissard B (2011) Factors predictive of ten-year mortality in severe anorexia nervosa patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 123:62–70. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01627

Arcelus J, Mitchell A, Wales J, Nielsen S (2011) Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68:724–731. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74

Huas C, Godart N, Caille A, Pham-Scottez A, Foulon C, Divac S, Lavoisy G, Guelfi JD, Falissard B, Rouillon F (2013) Mortality and its predictors in severe bulimia nervosa patients. Eur Eat Disord Rev 21:15–19. doi:10.1002/erv.2178

Suokas JT, Suvisaari JM, Gissler M, Löfman R, Linna MS, Raevuori A, Haukka J (2013) Mortality in eating disorders: a follow-up study of adult eating disorder patients treated in tertiary care, 1995-2010. Psychiatry Res 210:1101–1106. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.042

Nielsen S (2001) Epidemiology and mortality of eating disorders. Psychiatr Clin N Am 24:201–214. doi:10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70217-3

Crow SJ, Peterson CB, Swanson SA, Raymond NC, Specker S, Eckert ED (2009) Increased mortality in bulimia nervosa and other eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry 166:1342–1346. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09020247

Godart N, Flament MF, Perdereau F, Jeammet P (2002) Comorbidity between eating disorders and anxiety disorders: a review. Int J Eat Disord 32:253–270. doi:10.1002/eat.10096

Godart N, Perdereau F, Rein Z, Berthoz S, Wallier J, Jeammet P (2007) Comorbidity studies of eating disorders and mood disorders. Critical review of the literature. J Affect Disord 97:37–49. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.06.023

Lucas AR, Melton LJIII, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM (1999) Long-term fracture risk among women with anorexia nervosa: a population-based cohort study. Mayo Clin Proc 74:972–977. doi:10.4065/74.10.972

Lissner L, Odell PM, D’Agostino RB, Stokes J, Kreger BE, Belanger AJ, Brownell KD (1991) Variability of body weight and health outcomes in the Framingham population. N Engl J Med 324:1839–1844. doi:10.1056/NEJM199106273242602

Johnson JG, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW (2001) Health problems, impairment and illnesses associated with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder among primary care and obstetric gynaecology patients. Psychol Med 31:1455–1456. doi:10.1017/S0033291701004640

Arcelus J, Haslam M, Farrow C, Meyer C (2013) The role of interpersonal functioning in the maintenance of eating psychopathology: a systematic review and testable model. Clin Psychol Rev 33:156–167. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.009

Godart N, Perdereau F, Curt F, Lang F, Venisse JL, Halfon O, Bizouard P, Loas G, Corcos M, Jeammet P, Flament MF (2004) Predictive factors of social disability in anorexic and bulimic patients. Eat Weight Disord 9:249–257

Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Brook JS (2002) Eating disorders during adolescence and the risk for physical and mental disorders during early adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry 59:545–552. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.545

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2004) Eating disorders: Core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and related eating disorders. Clinical Guideline 9. http///www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/10932/29217/29217.pdf. Accessed 19 Oct 2015

American Psychiatric Association (2005) Treatment of Patients with Eating Disorders (3rd edition, text revision). American Psychiatric Association, Washington. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890423363.138660. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/eatingdisorders.pdf. Accessed 19 Oct 2015

Haute Autorité de Santé (2013) Guidelines, Anorexia Nervosa:Management. Haute Autorité de Santé, Paris. http://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/2013-05/anorexia_nervosa_guidelines_2013-05-15_16-34-42_589.pdf. Accessed 19 Oct 2015

Walsh JME, Wheat ME, Freund K (2000) Detection, evaluation and treatment of eating disorders, the role of the primary care physician. J Gen Intern Med 15:577–590. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.02439.x

Yeo M, Hughes E (2011) Eating disorders-early identification in general practice. Aust Fam Physician 40:108–111

Ogg EC, Millar HR, Pusztai EE, Alison S, Thom AS (1997) General practice consultation patterns preceding diagnosis of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 22:89–93. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199707)22:1<89:AID-EAT12>3.0.CO;2-D

Smink FR, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW (2012) Epidemiology of eating disorders: incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Curr Psychiatry Rep 14:406–414. doi:10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. Br Med J 339:b2700. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2700

Equator Network. (2010). Key reporting guidelines. http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/consort/. Accessed 19 Oct 2015

Van Son GE, Van Hoeken D, Van Furth EF, Donker GA, Hoek HW (2010) Course and outcome of eating disorders in a primary care-based cohort. Int J Eat Disord 43:130–138. doi:10.1002/eat.20676

King MB (1989) Eating disorders in a general practice population. Prevalence, characteristics and follow-up at 12 to 18 months. Psychol Med Monogr Suppl 14:1–34

King MB (1991) The natural history of eating pathology in attenders to primary medical care. Int J Eat Disord 10:379–387. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199107)10:4<379:AID-EAT2260100402>3.0.CO;2-I

Aguilar Hurtado ME, Sagredo Pérez J, Heras Salvat G, Estévez Muñoz JC, Linares López ML, Peña Rodríguez E (2004) Care by a primary care team for patients with eating behaviour disorders: identifying possibilities for improvement. Aten Primaria 34:26–31

Striegel-Moore RH, DeBar L, Wilson GT, Dickerson J, Rosselli F, Perrin N, Lych F, Kramer HC (2008) Health services use in eating disorders. Psychol Med 38:1465–1474. doi:10.1017/S0033291707001833

Van Son GE, Hoek HW, Van Hoeken D, Schellevis FG, Van Furth EF (2012) Eating disorders in the general practice: a case-control study on the utilization of primary care. Eur Eat Disord Rev 20:410–413. doi:10.1002/erv.2185

Turnbull S, Ward A, Treasure J, Jick H, Derby L (1996) The demand for eating disorder care. An epidemiological study using the general practice research database. Br J Psychiatry 169:705–712. doi:10.1192/bjp.169.6.705

Banasiak SJ, Paxton SJ, Hay P (2005) Guided self-help for bulimia nervosa in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med 35:1283–1294. doi:10.1017/S0033291705004769

Walsh BT, Fairburn CG, Mickley D, Sysko R, Parides MK (2004) Treatment of bulimia nervosa in a primary care setting. Am J Psychiatry 161:556–561

Durand MA, King M (2003) Specialist treatment versus self-help for bulimia nervosa: a randomised controlled trial in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 53:371–377

Waller D, Fairburn CG, McPherson A, Kay R, Lee A (1996) Nowell T (1996) Treating bulimia nervosa in primary care: a pilot study. Int J Eat Disord 19:99–103. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199601)19:1<99:AID-EAT12>3.0.CO;2-L

Garner DM, Garfinkel PE (1979) The eating attitudes test: an index of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med 9:273–279

Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE (1982) The eating attitudes test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med 12:871–878

Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH (1999) The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ 319:1467–1468. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1467

Henderson M, Freeman CPL (1987) A self-rating scale for bulimia. The “BITE”. Br J Psychiatry 150:18–24

Luce KH, Crowther JH (1999) The reliability of the eating disorder examination-self-report questionnaire version (EDE-Q). Int J Eat Disord 25:349–351. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199904)25:33.3.CO;2-D

Franke RH, Kaul J (1978) The Hawthorne experiments: first statistical interpretation. Am Soc Rev 43:623–643

Tonkin RS (1994) Practical approaches to eating disorders in adolescence: primer for family physicians. Can Fam Physician 40:299–304

Kreipe RE, Birndorf SA (2000) Eating disorders in adolescents and young adults. Med Clin North Am 84:1027–1049. doi:10.1016/S0025-7125(05)70272-8

Flahavan C (2006) Detection, assessment and management of eating disorders; how involved are GPs? Ir J Psych Med 23:96–99. doi:10.1017/S079096670000971X

Hill LS, Reid F, Morgan JF, Lacey JH (2010) SCOFF, the development of an eating disorder screening questionnaire. Int J Eat Disord 43:344–351. doi:10.1002/eat.20679

Mond JM, Myers TC, Crosby RD, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Morgan JF, LaceyJH Mitchell JE (2008) Screening for eating disorders in primary care: EDE-Q versus SCOFF. Behav Res Ther 46:612–622. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.003

Garcia-Campayo J, Sanz-Carrillo C, Ibañez JA, Lou S, Solano V, Alda M (2005) Validation of the Spanish version of the SCOFF questionnaire for the screening of eating disorders in primary care. J Psychosom Res 59:51–55. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.06.005

Tilsley L, Young M (2005) Eating disorders in primary care—are we doing enough? Pract Nurs 30:35

Isabel Hach I, Ruhl UE, Rentsch A, Becker ES, Türke V, Margraf J, Kirch W (2005) Recognition and therapy of eating disorders in young women in primary care. J Public Health 13:160–165. doi:10.1007/s10389-005-0102-5

Van Royen P, Beyer M, Chevallier P, Eilat-Tsanani S, Lionis C, Peremans L, Petek D, Rurik I, Soler JK, Stoffers HE, Topsever P, Ungan M, Hummers-Pradier E (2010) The research agenda for general practice/family medicine and primary health care in Europe. Part 3. Results: person centred care, comprehensive and holistic approach. Eur J Gen Pract 16:113–119. doi:10.3109/13814788.2010.481018

Button EJ, Benson E, Nollett C, Palmer RL (2005) Don’t forget EDNOS (eating disorder not otherwise specified): patterns of service use in an eating disorders service. Psychiatr Mar 29:134–136. doi:10.1192/pb.29.4.134

Soler J-K, Okkes I, Wood M, Lamberts H (2008) The coming of age of ICPC: celebrating the 21st birthday of the international classification of primary care. Fam Pract 25:312–317. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmn028

Colles SL, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE (2008) Loss of control is central to psychological disturbance associated with binge eating disorder. Obesity 16:608–614. doi:10.1038/oby.2007.99

Reid M, Williams S, Hammersley R (2010) Managing eating disorder patients in primary care in the UK: a qualitative study. Eat Disord 18:1–9. doi:10.1080/10640260903439441

Green H, Johnston O, Cabrini S, Fornai G, Kendrick T (2008) General practitioner attitudes towards referral of eating-disordered patients: a vignette study based on the theory of planned behavior. Ment Health Fam Med 5:213–218

Courtney EA, Gamboz J, Johnson JG (2008) Problematic eating behaviors in adolescents with low self-esteem and elevated depressive symptoms. Eat Behav 9:408–414. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2008.06.001

Jennifer Dixon J, Holland P, Mays N (1998) Primary care: core values developing primary care: gatekeeping, commissioning, and managed care. BMJ 317:125

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Aurelie Deniau, GP in Tours, who helped to collect data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No funding.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cadwallader, J.S., Godart, N., Chastang, J. et al. Detecting eating disorder patients in a general practice setting: a systematic review of heterogeneous data on clinical outcomes and care trajectories. Eat Weight Disord 21, 365–381 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0273-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0273-9