Abstract

Purpose

Previous research into the impact of pro-eating disorder (pro-ED) websites has predominantly been undertaken using experimental and survey designs. Studies have used both clinical and non-clinical (college student) samples. The present study aimed to explore the underlying functions and processes related to the access and continued use of pro-ED websites within a clinical eating disorder population using a qualitative research design.

Methods

Participants were recruited through NHS community mental health teams and specialist eating disorder services within South Wales, UK. Face-to-face semi-structured interviews were conducted with seven adult women in treatment for an eating disorder who had disclosed current or historic use of pro-ED websites. Interviewees ranged in age from 20 to 40 years (M = 31.2; SD = 7.8). Constructivist Grounded Theory was used to analyse interview transcripts.

Results

Five key themes were identified within the data, namely fear; ambivalence; social comparisons; shame; and pro-ED websites maintaining eating disordered behaviour. The pro-ED websites appeared to offer a sense of support, validation and reassurance to those in the midst of an eating disorder, whilst simultaneously reinforcing and maintaining eating disordered behaviour.

Conclusion

Themes are discussed in relation to implications and recommendations for clinical practice. Limitations of the present study and suggestions for future research are also outlined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Internet is a key source of information and there is large variation in the content and design of websites providing information on eating disorders. Some are designed by professional organisations and charities such as the NHS and Beating eating disorders (BEAT) [1], which aim to support individuals to address difficulties with food, weight and shape. Others, termed pro-anorexia, pro-bulimia, or pro-eating disorder (pro-ED) websites promote an attitude that eating disorders are a ‘lifestyle choice’.

Many existing studies into the use of pro-ED websites have utilised experimental designs or have conducted content analyses of websites and forums. Whilst some pro-ED websites display superficial regard to the notion that eating disorders are bad, the pro-ED content, “Undeniably validates the anorexic ‘lifestyle’ and provides the tools to allow people to continue it and to hide it from their family and friends” [2, p. 546]. In a review of 180 active pro-ED websites, 83 % provided overt suggestions on how to engage in eating-disordered related behaviours [3]. This might be via ‘tips and tricks’ sections to maintain the eating disorder, including distraction and deception techniques to aid food restriction [4] or “thinspiration” pages which aim to promote and sustain motivation to restrict food through ‘inspirational’ quotes and photographs of emaciated bodies [5].

Experimental studies using non-clinical populations, such as college students have demonstrated that exposure to pro-ED websites in comparison to neutral sites may adversely impact on a range of variables including affect, appearance self-efficacy, self-esteem, perfectionism, drive for thinness, perceived attractiveness, and calorie intake [6–11]. However, findings have not been consistently replicated. One experimental design involving a sample of normal weight (BMI 18.5–25) female undergraduates demonstrated that those exposed to pro-ED website content later rated greater body satisfaction than controls [12].

Questionnaire-based studies with individuals exhibiting eating disordered behaviour have indicated that viewership of pro-ED websites and forums is associated with mental stress [13]; dysregulated eating patterns [14]; greater length of hospital stay and a less favourable prognosis [15]. In contrast, a grounded theory analysis of online interviews with 33 pro-ED blog authors suggested that pro-ED websites fulfilled a supportive role which was perceived to be unavailable in ‘offline’ relationships [16]. Responses suggested that the stigmatised social perception of eating disorders, in particular anorexia, contributed to social isolation in real world environments. Online blogs were argued to provide a safe and non-critical audience whereby individuals gained a sense of community and unconditional support.

In the largest online survey of pro-ED website users to date, with a sample of nearly 1,300 individuals, the most frequently cited reasons to access pro-ED websites were motivation for weight loss, weight loss tips, meeting people and curiosity [17]. Findings demonstrated that 61 % reported implementing new weight loss or purging methods; 37 % used laxatives, diet pills or weight loss supplements; and 55 % admitted to changing eating habits following pro-ED website use. Correlational analyses showed a significant association between heavy (frequent and prolonged) website use and more extreme and harmful weight loss behaviours using clinical measures of eating disorder behaviour (EDE-Q) and quality of life (EDQOL). However, despite this finding, many pro-ED users reported positive aspects of websites use, predominantly in terms of social support [17].

Causality cannot be presumed due to the correlational and cross-sectional methodology; nonetheless, the average age of initial use of pro-ED sites was greater than the reported age of onset of eating difficulties. Consequently, the authors suggest a possible progression from the development of eating difficulties into pro-ED websites usage, rather than pro-ED website use leading to an eating disorder [17]. Similarly, in a review of eight studies examining the effects of viewing pro-ED websites, Talbot [15] proposed that such websites may increase eating disorder related behaviours but may not cause it.

One important consideration is the way in which users engage with the websites. An online survey of 150 international pro-ED website users highlighted disparity between users’ online behaviour. ‘Passive’ users were silent observers of pro-ED websites and reported browsing tips and tricks sections significantly more than ‘Active’ users. Silent browsing to sustain eating disordered behaviour was found to be particularly harmful. The authors argue that direct interaction with other website users experienced by ‘Active’ users may help ‘buffer’ the potentially damaging content of the pro-ED websites. In contrast, ‘Passive’ users who are exposed to pro-ED content in the absence of emotional support may be more vulnerable to the adverse impact of pro-ED websites [18]. Therefore, further research is required to understand if and how exposure to pro-ED websites impacts on the causal pathways of eating disordered behaviour.

A systematic review of 26 peer reviewed articles regarding risks of pro-ED websites highlighted three major themes [19]. Such websites were found to operate under the pretext of support, in that support offered is superficial and conditional. They appeared to reinforce disordered eating behaviour through the inclusion of extreme weight loss tips and tricks and competition amongst users. This is supported by the association of pro-ED website use and increased eating disordered behaviour [17]. Finally, the websites acted as a barrier to recovery mediated through ‘anti-recovery’ connotations and the provision of concealment strategies [19].

A recent meta-analysis of nine studies examined effect sizes in relation to the impact of pro-ED websites on eating pathology [20]. Significant effect sizes were present in terms of the impact of pro-ED websites exposure on dieting, body image satisfaction and negative affect. Interestingly, no effect was evident for symptoms associated with bulimia, although the non-significant finding may be attributed to the small number of studies assessing bulimia within the meta-analysis. The authors concluded with a call for enforceable regulation of pro-ED websites.

Overall, the relationship between pro-ED websites and eating related attitudes and behaviours appears complex and requires further investigation. Whilst analyses of pro-ED website content and surveys among users have been undertaken, at present there is a lack of published findings following face-to-face interviews with pro-ED website users in a clinical eating disorder population. This type of exploratory work is needed to enhance the understanding of the underlying function and processes related to the access and continued use of such websites.

Purpose of the study

The research aims to investigate, through in-depth interviews, the function of pro-ED websites from the perspective of individuals with an eating disorder who have experienced such websites. The research aims to explore the mechanisms through which they initially viewed pro-ED websites, and their perceptions regarding the impact of pro-ED website use.

Method

Participants

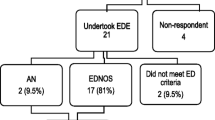

Participants were recruited through a Community Mental Health Team (CMHT) and a specialist eating disorder service within two NHS Health Boards in South Wales. Seven women took part in the study, ranging in age from 20 to 40 years (M = 31.2; SD = 7.8), six of whom described themselves as White British and one participant was Central European.

Participants had experienced eating difficulties for between 6 and 24 years (M = 13.5; SD = 7.9). All participants reported having undertaken both restricting (anorexia presentation) as well as bingeing and purging (bulimia presentation) behaviours throughout their eating difficulties. Whilst all participants were receiving current treatment for an eating disorder, at the time of interview no participant appeared to be at a BMI that would attract a formal diagnosis of anorexia nervosa.

The research received favourable ethical approval by the National Institute for Social Care and Health Research (NISCHR) Research Ethics Service for Wales. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Interview protocol

A semi-structured interview was devised to explore participants’ experiences of pro-ED websites. A clinical psychologist working in an NHS specialist eating disorder service and a service user representative provided consultation in the development of the interview schedule. Areas of exploration included how and why the interviewee initially used pro-ED websites; type of website use (frequency, triggers and degree of online interaction); the impact of the websites on themselves, their relationships and their recovery; and their opinions of pro-recovery websites.

Procedure

Clinicians working in the CMHT and specialist eating disorder service who had agreed to support the recruitment of participants were provided with research information and asked to provide participant information sheets to those clients who had previously disclosed use of pro-ED websites. The principal researcher contacted all individuals who expressed an interest in taking part in the study. Interviews took place on an individual basis within the NHS premises that participants attended for treatment. Informed consent was gathered prior to commencement of the interview. Basic demographic information was collected. Data collection took place between 2013 and 2014. Interviews were audio recorded and ranged in duration from 45 min to 1 h. Interviews were transcribed within 1 week of the interview date.

Data analysis

Qualitative methodologies are concerned with exploring how individuals experience and make sense of the worlds they live in. Grounded theory (GT), which aims to produce and develop a model from the data, was used in the analysis of transcripts. GT provides an explanatory framework to understand phenomena and is consequently often used for the exploration of new areas of research [21]. Whilst the GT methodology was originally developed by Glaser and Strauss [22], divergent perspectives regarding the process and application of GT were subsequently developed.

Constructivist GT [21] holds social construction epistemology at its core. The approach highlights the role of the researcher as co-constructor in the research, as opposed to a passive observer on the discovery of an objective reality. In its endeavour to develop a co-constructed experience of the world from the researcher and participant’s perspective, constructivist GT does not strive to result in a ‘complete’ theory of a phenomenon [21]; as uncovering the objective truth is at odds with its epistemological positioning. Grounded theory allows for interview schedules to be tailored according to previous interviews using theoretical sampling (further data collection following the development of categories). Theoretical sampling is fundamental to GT and strives to ensure that the emerging theory develops rigor and parsimony [23]. The interview schedule was expanded upon for subsequent interviews, in accordance with theoretical sampling.

All transcripts were initially coded using open coding; which involves labelling units of data, such as sentences with short, action focused words. Focused coding was then implemented, which encompasses identifying the most “significant and/or frequent earlier codes to sift through large amounts of data” [21, p. 57]. Theoretical coding was then implemented which organises subcategories to higher order conceptual categories. Theoretical coding is used to develop the emerging theory within grounded theory, and helps, “to tell an analytic story that has coherence” [21, p. 63.] All transcripts were analysed according to this process, therefore, the final themes reflect data from all seven interview transcripts.

Throughout data collection and analysis, a reflective journal was kept by the principal author as recommended within constructivist GT [21] and supervision with the wider research team facilitated transparency and reflexivity. A colleague outside of the research team who was undertaking an unrelated research project using constructivist GT was consulted through various stages of analysis.

Results

Whilst all interviewees were recruited from eating disorder treatment services, individuals reported being at different stages of their recovery. Five key themes were identified within the interviews; direct quotes are used to illustrate themes. The results relate to the experiences of the seven participants within the study, and may not represent the views of all people who use pro-ED websites.

Fear

This theme refers to the anxiety expressed by the interviewees in relation to the anticipated consequences of recovery. Many participants initially feared the implications of recovery, specifically weight gain. For individuals who were further into their recovery, some reported a fear of using pro-ED websites due to perceptions that use of the websites could increase their risk of relapse.

Some individuals described fear regarding an external pressure to recover, reporting that they were afraid of being pressured into treatment, particularly if they disclosed their eating practices to others, and appeared to turn to pro-ED websites to help with that fear:

P4

Although you’re obviously in the system and you’re in “recovery” and you’re trying to recover, there’s that part of you that actually doesn’t want to, and it kind of fuels that how can I how can I stop, you know how can I stop them making me recover.

Losses associated with recovery from an eating disorder appear to be a lack of control and a lost eating disorder identity:

P1

I feel like the eating disorder is one thing that I was good at, and now I’m not even good at that anymore… And that can be quite demotivating.

Fear and loss associated with recovery, in addition to a perception of being forced into treatment, led some individuals to use pro-ED websites to superficially engage in treatment.

P4

They [pro-ED websites] kind of give you hints and tips as to how to fool people into thinking that you are getting better and putting on this front where you’ve got, you don’t want to recover but you want to make people believe that you are.

Likewise, some individuals described difficult experiences within treatment services, in particular feeling threatened or pressurised during treatment. Such experiences appeared to encourage the use of pro-ED websites to defend against the perceived pressure to change during treatment.

P1

I wasn’t always involved with a nice team of people like [therapist], and uh yeah I had quite a tough time …. I was getting shouted at … it just didn’t work for me and so I felt quite put into a corner.

One participant reported that they had turned to pro-ED websites for support after perceiving their treatment team to be harsh and punitive. However, many interviewees reported positive experiences of current treatment services. Empathy and non-judgemental support was considered to be crucial when engaging in treatment for their eating disorder. Some participants reported implementing particular skills that they had learned in treatment to cope if they had thoughts about returning to pro-ED websites.

Ambivalence

Many interviewees expressed ambivalence both about their eating disorder and the degree to which their use of pro-ED websites was helpful and acceptable. Many respondents described an inner battle regarding their eating disorder alongside their use of pro-ED websites:

P1

I always think of kind of having an anorexic voice and a normal voice and they almost sometimes they feel like two different people.

Many individuals described continuing to use pro-ED websites despite feeling guilty:

P4

Part of you that goes I shouldn’t be looking at them at the same time…there’s kind of like guilt at the same time.

Whilst interviewees appeared to acknowledge risks of eating disorders and the use of pro-ED websites, many minimised the perception of risks to the self. Sometimes they would choose to compare themselves to other pro-ED websites users who they perceived to have more of a problem:

P2

I guess it egged me on a lot like I think the sense of feeling like I didn’t really have a problem because I’d always look at the people on there as being like sad, like they had the problem and I was just you know not like them.

At other times respondents appeared to use pro-ED websites to seek reassurance and strengthen their argument that weight restriction was normal and healthy. Participants would often focus on ‘healthy looking’ thin images on websites, and ignore the ‘ill’ looking images to support the argument that restrictive eating was not dangerous. Many could see that behaviours associated with an eating disorder could be risky; however, they did not consider themselves to be at risk.

Interviewees described using information and support from pro-ED websites in order to reduce the credence of messages received by others, including family and professionals that eating disorders are dangerous and should be ‘treated’. Accordingly, individuals appeared to use pro-ED websites to protect the eating disorder. The pro-ED websites were used to reduce internal doubts regarding the risks of the eating disorder and to fight against others who argue that food restriction and extreme weight control is dangerous:

P1

It [pro-ED website] helps bolster my own opinion and reaffirm my own opinion that that’s right, whereas all the medical people that I’m seeing especially trying to always knock away and say weight loss is bad and all these consequences and you feel like you’re in a corner, and actually then you got this group of people that are saying ‘you’re alright, keep going.

The view of pro-ED websites changed for interviewees further through their recovery. All respondents appeared to perceive pro-ED websites to be helpful, supportive and functional whilst in the midst of their eating disorder. The websites provided reassurance that the eating disorder was a lifestyle choice rather than an illness, which helped individuals to feel more in control of their eating difficulties. However, for those who were further into recovery, the websites were viewed as dangerous. Some interviewees made a conscious decision to disengage from the websites in order for them to attempt to engage fully in treatment.

P1

I guess looking back on it now there was many unhelpful things, giving tips and tricks on how to lose weight…. people just saying no you can‘t eat, go even lower, that’s not helpful now I realise although it was then.

Interestingly, despite some individuals continuing to use the websites, all respondents reported that they would warn others against using pro-ED websites:

P2

I’d try to get them to stay away from them [pro-ED websites].

When discussing the impact of pro-recovery websites, they were perceived to be patronising, too brief and focused on teenagers rather than working age adults. Consequently, the acceptability and utility of pro-recovery websites were questioned by the sample, with many feeling excluded from pro-recovery websites. None of the interviewees expressed positive experiences of pro-recovery websites. The development of more service-user informed pro-recovery websites may enhance their effectiveness and consequently, may prevent some individuals from seeking support on pro-ED websites.

Social comparisons

Interviewees defined personal achievement through their weight loss. They often compared themselves to individuals on pro-ED websites which could lead to feelings of inadequacy, jealousy and failure if unfavourable comparisons were made. In contrast, favourable comparisons led to feelings of pride and increased self-esteem. Comparisons with other users often made participants work ‘harder’ at their eating disorder:

P6

So it’s motivation in that sense that they’ve got to that point that their picture is now on there because people admire how they look, so it motivates you to do it.

Out of the seven individuals interviewed, only one reported that she had interacted and posted content on the websites. The remaining interviewees read and observed the websites. Some described feeling inferior to other website users and did not feel ‘worthy’ to post on the websites. Some reported feeling like an ‘imposter’ and anticipated rejection if they interacted on websites. Others were concerned that their anonymity could be compromised if they posted online.

P2

I always kind of felt um inferior if anything I’d say, I think that’s one of the main reasons I never really used them properly… I guess I kind of felt like an amateur, like kind of wannabe kind of thing.

Shame

The stigma of using pro-ED websites was highlighted by many interviewees. Some believed that using pro-ED websites was more shameful and less acceptable than having an eating disorder. It appeared that the eating disorder could be viewed as an ‘illness’, potentially attracting empathy from others. In contrast, using pro-ED websites was considered to represent a choice to maintain the eating disorder, actively ‘sabotaging’ recovery. Consequently, interviewees often used the websites secretly and privately:

P3

I just felt it was just like almost worse than the eating disorder itself and that it was like a really like a conscious thing to be promoting my eating disorder and doing what I can to hold on to it.

Whilst many interviewees expressed feelings of shame at using the websites, paradoxically, the websites also served to normalise their experiences, which appeared to reduce shame associated with their eating disorder. Individuals often described feeling different from others, which resulted in social isolation. Using pro-ED websites was one way of feeling connected to other people. Interviewees appeared to believe that others would not understand their extreme weight loss behaviours, resulting in a reluctance to disclose the eating disorder to ‘real’ people. Thus, individuals turned to the accessibility and anonymity of the Internet to research weight loss tips and experiences.

P6

It was comforting to know that I wasn’t the only one thinking the way I was that there were other people who thought exactly the same.

Pro-ed websites maintaining eating disordered behaviour

All interviewees reported learning and implementing tips online to increase eating disordered behaviour. The websites appeared to encourage and glamorise high risk behaviour.

P5

I learned how to how to throw up and I think yeah I could do that again it would be quite easy. And if you eat a bit of baking powder with it, it goes even better because that’s one of the tricks on the websites, never forget it.

However, all noted that they experienced eating difficulties before using pro-ED websites.

The websites were perceived to provide a sense of support and validation regarding the eating disorder, reaffirming attitudes and beliefs which maintain the eating disorder.

P1

It was kind of everything that my eating disorder was saying to me was written in front of me so it’s more of a reaffirming thing.

Many described using the websites for motivation when they felt hungry, weak or self-critical.

P1

I felt renewed motivation [after using pro-ED websites], um, so it would often lead to me restricting more that day or doing some more exercise, it would have a temporary step up of the eating disorder behaviour.

Some individuals also described using the websites as a form of self-harm behaviour; in that they used pro-ED websites as a punishment when they had eaten or binged.

P2

I guess if it was on days where maybe I hadn’t lost any weight or I’d ate more than I felt comfortable with and then I went on then, it would be almost like I was going on to make myself feel useless.

Discussion

The pro-ED websites appeared to offer a sense of support, validation and reassurance to those in the midst of an eating disorder, whilst simultaneously reinforcing and maintaining eating disordered behaviour. The websites bolstered the sense of pride and achievement experienced through weight loss. Comparisons with other users served to enhance competition and drive to work harder at the eating disorder. Websites were often used to support and motivate food restriction, and promoted superficial engagement with treatment services. At times the websites were used as a method of punishment when individuals experienced self-criticism. For those in recovery the websites were feared and they made a conscious effort to avoid them, recognising the negative impact they had on their recovery.

Only one interviewee reported actively posting on pro-ED websites. Some individuals appeared to anticipate rejection from the online community which led to passive observing of the websites. Ultimately, individuals appeared to view the websites as helpful when in the midst of their eating disorder. However, for those who were actively working towards recovery, many reflected on their beliefs that pro-ED websites are dangerous in influencing vulnerable individuals and maintaining eating disordered behaviour.

The websites were often used to reduce a sense of social isolation, fuelled by stigma and shame associated with the eating disorder and use of pro-ED websites. During treatment the fear of recovery, of weight gain and loss of ED identity could lead people to seek out the websites. Then they used the content to gauge how they were doing, comparing themselves to those they saw on the websites and to support their beliefs that they were not ill but were making healthy choices.

The use of pro-ED websites has been described as a barrier to recovery and may undermine therapeutic work through the promotion of superficial engagement and deception during treatment. Clinicians should be aware of the accessibility of pro-ED websites and develop an understanding of how shame and stigma regarding pro-ED websites may lead to secrecy and reluctance to disclose their use.

It is anticipated that clinicians routinely assess for high-risk behaviours such as laxative use and purging. However, actively avoiding the exploration of pro-ED website use may reinforce the ‘guilty secret’ that individuals using such websites may experience, thus clinicians need to find a way to explore pro-ED website use. Such an assessment could begin by asking individuals about general website use and the methods they use to source information and support related to their eating difficulties.

Due to the ego-syntonic nature of eating disorders, many individuals do not view the behaviour as problematic, and are likely to resist treatment attempts due to reluctance to ‘give up’ the positive aspects of the eating disorder [24]. When individuals feel pressured into recovery, use of pro-ED websites may be a means of protecting their eating disorder, undermining attempts to facilitate change. Therefore, it is important to consider an individual’s readiness for recovery. Prior motivational work may reduce a fear of recovery and a feared pressure to recover which may underlie the use of pro-ED websites.

Furthermore, denial, resistance to change and avoidance of treatment may result in difficulties establishing therapeutic relationships [25]. Shame and fear of judgement regarding the use of pro-ED websites seem to enhance a sense of social isolation which appears to motivate continued use of pro-ED websites. It is important that individuals feel both accepted and understood by treatment services, alongside a belief that individuals are capable of, and are expected to change. An empathic stance regarding both the individual’s eating disorder and use of pro-ED websites is crucial in order to develop trust and safety within the therapeutic relationship.

Participants within the current sample expressed that they felt excluded from some pro-recovery websites. Criticisms of pro-recovery websites included material being specifically targeted towards adolescent females, information appearing biased and discounting any positive aspects of eating disorders, and perceiving the content to be brief, patronising and at times critical of individuals with eating disorders. It was suggested that pro-recovery websites could focus on sharing personal experiences and detailing journeys of recovery, as opposed to focusing on factual accounts of eating disorders. Greater engagement with service users in the design of these sites would help to improve their relevance.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first published study arising from face to face interviews with individuals who have used pro-ED websites in the context of an eating disorder. Given the nature of the research question, recruitment was always going to be challenging and the research would have benefited from an increased sample size, a wider ethnic diversity and inclusion of male participants within the sample. Individuals with severe eating disorders were not included in the sample which also limits the generalizability of findings. In addition, only basic demographic information of participants was collected. Notwithstanding the limited sample size, saturation of themes did begin to emerge within interview transcripts.

The present research offers a preliminary conceptualisation concerning the views of individuals in treatment for eating disorders regarding their use of pro-ED websites. Individuals within this sample had sought the assistance of NHS treatment services for their eating difficulties. Arguably, those who do not seek treatment may be in greater need of appropriate, accessible and effective online support in the form of pro-recovery websites. Future qualitative research with individuals both within and outside of treatment services is important to further knowledge in the area. Due to the wide-spread universal nature of pro-ED websites, it may be useful to conduct qualitative analyses with individuals outside of the UK. Treatment services outside of the NHS may respond differently to pro-ED websites, particularly where health-care is not provided by the state.

A greater understanding of the mechanisms underpinning pro-ED website use may allow treatment providers to incorporate pro-ED website use, a perpetuating factor in the course of an eating disorder, into treatment plans. This has the potential to enhance the specificity and effectiveness of treatment. Therapists’ avoidance of pro-ED websites during treatment may inadvertently contribute to and exacerbate the secrecy and shame associated with such website use. Therefore, an open dialogue about all maintaining factors of the eating disorder is crucial.

Finally, the findings highlight the importance of supporting therapists to adopt a non-judgemental attitude towards pro-ED websites, in order to reduce the sense of stigma and enhance openness with service users. Therefore, exploration of clinicians’ perspectives of pro-ED websites would be useful in the development of appropriate training for therapists and opening up the discussion about pro-ED websites.

References

Beating eating disorders website. http://www.b-eat.co.uk

Lipczynska S (2007) Discovering the cult of Ana and Mia: a review of pro-anorexia websites. J Ment Health 16(4):545–548. doi:10.1080/09638230701482402

Borzekowski DL, Schenk S, Wilson JL, Peebles R (2010) e-Ana and e-Mia: a content analysis of pro-eating disorder web sites. Am J Public Health 100(8):1526–1534. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.172700

Harshbarger JL, Ahlers-Schmidt CR, Mayans L, Mayans D, Hawkins JH (2009) Pro anorexia websites: what a clinician should know. Int J Eat Disord 42(4):367–370. doi:10.1002/eat.20608

Norris ML, Boydell KM, Pinhas L, Katzman DK (2006) Ana and the internet: a review of pro-anorexia websites. Int J Eat Disord 39(6):443–447. doi:10.1002/eat.20305

Theis F, Wolf M, Fiedler P, Backenstrass M, Kordy H (2012) Eating disorders on the internet: an experimental study on the effects of pro eating disorders websites and self-help websites. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 62(2):58–65. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1301336

Juarez L, Soto E, Pritchard ME (2012) Drive for muscularity and drive for thinness: the impact of pro-anorexia websites. Eat Disord 20(2):99–112. doi:10.1080/10640266.2012.653944

Jett S, LaPorte DJ, Wanchisn J (2010) Impact of exposure to pro-eating disorder websites on eating behaviour in college women. Eur Eat Disord Rev 18(5):410–416. doi:10.1002/erv.1009

Custers K, Den Bulck Van (2009) Viewership of pro-anorexia websites in seventh, ninth and eleventh graders. Eur Eat Disord Rev 17(3):214–219. doi:10.1002/erv.910

Bardone-Cone AM, Cass KM (2007) What does viewing a pro-anorexia website do? An experimental examination of website exposure and moderating effects. Int J Eat Disord 40(6):537–548. doi:10.1002/eat

Bardone-Cone AM, Cass KM (2006) Investigating the impact of pro-anorexia websites: a pilot study. Eur Eat Disord Rev 14(4):256–262. doi:10.1002/erv.714

Delforterie MJ, Larsen JK, Bardone-Cone AM, Scholte RH (2015) Effects of viewing a pro-ana website: an experimental study on body satisfaction, affect, and appearance self-efficacy. Eat Disord 22(4):321–336. doi:10.1080/10640266.2014.898982

Eichenberg C, Flumann A, Hensges K (2011) Pro-ana communities on the internet. Psychotherapeut 56(6):492–500. doi:10.1007/s00278-011-0861-0

Ransom DC, La Guardia JG, Woody EZ, Boyd JL (2010) Interpersonal interactions on online forums addressing eating concerns. Int J Eat Disord 143(2):161–170. doi:10.1002/eat.20629

Talbot TS (2010) The effects of viewing pro-eating disorder websites a systematic review. West Indian Med J 59(6):686–697. doi:10.1002/wps.20195

Yeshua-Katz D, Martins N (2013) Communicating stigma: the pro-ana paradox. Health Commun 28(5):499–508. doi:10.1080/10410236.2012.699889

Peebles R, Wilson JL, Litt IF, Hardy KK, Lock JD, Mann JR, Borzekowski DLG (2012) Disordered eating in a digital age: eating behaviors, health, and quality of life in users of websites with pro-eating disorder content. J Med Internet Res 14(5):e148. doi:10.2196/jmir.2023

Csipke E, Horne O (2007) Pro-eating disorder websites: users’ opinions. Eur Eat Disord Rev 15(3):196–206. doi:10.1002/erv.789

Rouleau CR, von Ranson KM (2011) Potential risks of pro-eating disorder websites. Clin Psychol Rev 31(4):525–531. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.12.005

Rodgers RF, Lowy AS, Halperin DM, Franko DL (2015) A meta-analysis examining the influence of pro-eating disorder websites on body image and eating pathology. Eur Eat Disord Rev. doi:10.1002/erv.2390

Charmaz K (2003) Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage, London

Glaser BG, Strauss AL (1967) The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago

Jones M, Alony I (2011) Guiding the use of grounded theory in doctoral studies: an example from the australian film industry. Int J Dr Stud 6:95–114

Cooper MJ (2005) Cognitive theory in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: progress, development and future directions. Clin Psychol Rev 25:511–531. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.01.003

Vitousek K, Watson S, Wilson GT (1998) Enhancing motivation for change in treatment-resistant eating disorders. Clin Psychol Rev 18(4):391–420. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00012-9

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gale, L., Channon, S., Larner, M. et al. Experiences of using pro-eating disorder websites: a qualitative study with service users in NHS eating disorder services. Eat Weight Disord 21, 427–434 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0242-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0242-8