Abstract

Objective

This study is the result of two Portuguese case–control studies that examined the replication of retrospective correlates and preceding life events in anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN) development. This study aims to identify retrospective correlates that distinguish AN and BN

Method

A case–control design was used to compare a group of women who met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition criteria for AN (N = 98) and BN (N = 79) with healthy controls (N = 86) and with other psychiatric disorders (N = 68). Each control group was matched with AN patients regarding age and parental social categories. Risk factors were assessed by interviewing each person with the Oxford Risk Factor Interview.

Results

Compared to AN, women with BN reported significantly higher rates of paternal high expectations, excessive family importance placed on fitness/keeping in shape, and negative consequences due to adolescent overweight and adolescent objective overweight.

Discussion

Overweight during adolescence emerged as the most relevant retrospective correlate in the distinction between BN and AN participants. Family expectations and the importance placed on keeping in shape were also significant retrospective correlates in the BN group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Eating disorders (ED) are among the 10 leading causes of disability in young women [1, 2]. Anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN) have been consensually described as severe psychiatric disorders that primarily affect adolescents or young women [3]. Both typically start in the middle of adolescence because of food restriction onset [4, 5]. AN and BN are characterized by an over-evaluation of weight and body shape and a conviction about the power in their control [6–8]. In approximately 10–20 %, AN is intractable and continuous [8–13]; mortality rate has been estimated to be between 5 and 5.6 % per decade with AN associated with a 50 times higher suicide risk [4, 14]. BN is usually described as having a chronic course with remission over time ranging from 31 to 74 % [5].

ED have been conceptualized as heterogeneous disorders with a multifactorial etiology involving a complex interaction between genes and environment [2, 15, 16].

According to Schmidt [17], the main types of studies used in the investigation of risk factors are cross-sectional studies with case–control designs and prospective longitudinal studies with cohorts of subjects. Numerous factors have been identified in the development of ED. However, the results obtained from several studies are difficult to understand. Several of the primary critics advocate that (a) most of the researches have investigated a limited number of potential risk factors; (b) the methods used in these studies did not allow for the prediction of ED onset, and did not control initial symptoms or risk factors precedence; and (c) there are few studies that address control groups with other psychiatric disorders and control groups with other ED [18–20].

Studies that assessed risk factors for AN and BN using the Oxford Risk Factors Interview (RFI) addressed several of the limitations cited in the previous research using an interview to establish a diagnosis and the precedence of the risk factor evaluated and by considering a wide array of potential risk factors. Regarding AN risk factors, Fairburn’s [18] study found perfectionism and negative self-evaluation were specific retrospective correlates for AN development. Temperamental traits, sexual abuse and parental pressure increased the risk for developing AN in Karwautz’s [21] study. Pike’s [22] study showed that women with AN had significantly higher rates of negative affectivity, perfectionism, family discord and higher parental demands. Karwautz et al. [23] found that disruptive events, interpersonal problems and dieting environment increased the risk for AN independent of genotype. Finally, Machado et al. [24] showed that women with AN reported significantly higher rates of perfectionism, negative attitudes toward parents’ shape and weight, significant concern regarding feeling fat and family history of AN or BN. In assessing BN risk factors with the Oxford RFI, Fairburn et al. [19] found that exposure to factors that were likely to increase the risk for dieting and negative self-evaluation and certain parental problems (such as alcoholism and obesity) were substantially more common among those with BN. Day et al. [25] investigated risk factors, correlations and markers associated with early-onset BN and showed that adolescents with early-onset BN were more likely to report an earlier age of menarche. Recently, Gonçalves et al. [26] found that childhood overweight was the most significant BN retrospective correlates.

To our knowledge, only two studies used RFI and compared AN and BN risk factors. Fairburn et al. [18] using psychiatric and non-psychiatric control groups, found that parental obesity was the only retrospective correlate that distinguished both ED, with BN participants having higher rates of exposure; childhood obesity, which was also higher in BN participants, had marginally significant results. Hilbert et al. [27] studied the risk factors across ED comparing with non-psychiatric controls and concluded that all retrospective correlates for BN were shared by individuals with either AN or Binge Eating Disorder (BED). Considering that only two studies explored retrospective correlates that differentiate AN and BN, replication with different samples will shed light on the stability and power of such correlates. Therefore, the present study aims to contribute to the literature by expanding our knowledge about the differences between AN and BN etiology targeting to transfer to practice the input of scientific knowledge.

In previous studies we used RFI and compared AN and two control groups [24] and BN and two control groups [26]. In the present study, we aim at contributing to the understanding of the differences between AN and BN etiology. We used a case–control design with two control groups (healthy controls and controls with other psychiatric disorders) and, we compared AN participants with BN participants around a primary objective: identify retrospective correlates that distinguish AN and BN. We included participants of the previous studies and added new ones.

Method

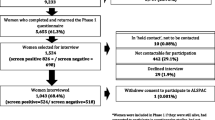

Recruitment procedure

Participants who met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV [28]) for AN or BN were recruited from specialized ED treatment settings. Psychiatric control (PC) group participants were also recruited from treatment settings. Potential non-psychiatric control (normal control; NC) group participants were recruited from schools and a university campus (healthy control group).

Exclusion criteria for all four groups were physical disorders likely to influence eating habits or weight, psychosis or current pregnancy. Inclusion criteria for the NC group were absence of past or current clinically significant ED or other psychiatric disorder. Inclusion criteria for the PC group included a current DSM-IV Axis I diagnosis and no previous or present history of ED symptoms.

Participants

Participants in this study were 98 women with a DSM-IV [28] diagnosis of AN (n = 63 restricting type and n = 35 binge eating/purging type); 79 women with diagnosis of BN (n = 72 binge eating/purging type and n = 7 non purging type); 68 women with current Axis I DSM-IV psychiatric diagnoses other than ED (PC group); and 86 women with no psychiatric disorder diagnosis (NC group). Of these, 86 women with AN, 60 with BN and 154 participants from both control groups were already evaluated in two studies described elsewhere [24, 26] using a conditional logistic regression analysis appropriate for a case–control design with individual matching.

PC group participants had the following primary DSM-IV diagnosis: anxiety disorder (n = 35; 51.4 %) and depressive disorder (n = 32; 47.1 %); one PC group member had a current diagnosis of somatoform disorder.

The NC and PC participants were individually matched to the participants with AN based on current age (±1 year) and parental socioeconomic status (within two parental socioeconomic status categories) and were assigned an index age corresponding to the index age of AN to which they were matched. Both control groups were questioned about their life until the age of onset of disturbed eating (index age) of their particular matched subject with AN. Index age was conservatively defined as the age at onset of at least one of the following symptomatic behaviors [18, 19, 22]: sustained dieting, sustained overeating, sustained purging (as determined by the Oxford RFI), rather than the age at which the participants first met all the criteria for an ED diagnosis. The assessment of risk factors focused on the period prior to the index age, thereby ensuring that the risk factor preceded the onset of clinically significant eating pathology [22]. Adjusting case–control comparisons for age at onset (i.e., index age) minimized differences in the time the participants were exposed to the risk factor [18].

Assessment

Diagnostic assessment

Current and lifetime psychiatric disorders were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-IV [29]). ED diagnosis and psychopathology were assessed with the diagnostic items of the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE [30]). The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q [31]) was used as the primary instrument to screen potentially healthy controls.

Risk factor assessment

Exposure to putative risk factors for ED was assessed with the Oxford Risk Factor Interview for Eating Disorders (RFI [19]). Each woman in the four groups was interviewed (there were no additional informants). The interviews focused on the period before the onset of the ED (retrospective reporting), with age of onset being defined as the age at which the first significant and persistent eating pathology behaviors began [19]. For risk factors believed to have a hereditary component (e.g., family history of psychiatric disorders and parental overweight and obesity) the interview focused on both the pre and post disorder onset period. The RFI was investigator-based and used behavioral definitions of key concepts to minimize problems related to retrospective data [18]. Many putative risk factors were assessed (Tables 2, 3). They were categorized into one of three domains: personal vulnerability domain, environmental domain and dieting vulnerability domain. Within each domain, we organized risk factors into several subdomains to reflect certain types of exposure. Additional risk factors were also evaluated (e.g., menarche age). The degree of exposure to a potential risk factor was rated on a five-point rating scale ranging from 0 = no exposure to 4 = high severity, long duration, or high frequency of exposure. A score of 3 or 4 was considered to indicate significant severity, duration, or frequency of exposure.

Socioeconomic status

An adaptation of the Graffar schedule [32] was used in which scores ranged from 5 to 25, with higher scores indicating lower socioeconomic level. This schedule considers the years of formal education and profession of the parents, sources of income, and type of housing and neighborhood to assign the family to one of 5 socioeconomic status categories.

Procedure

Participants in the AN and BN groups had been previously diagnosed by clinicians and were then interviewed using the EDE diagnostic items [19]. The PC group participants had a previous diagnosis by a clinician; however, true case status was established and confirmed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I [29]). Participants in the NC group were screened using the EDE-Q [31]. They were selected using the following criteria: (a) score < 4 on all the 4 EDE-Q subscales and (b) absence of dysfunctional eating behaviors (i.e., binge eating episodes and inappropriate weight control methods). They were also interviewed with the SCID-I [29] to rule out any DSM-IV diagnosis. Participants of both control groups were interviewed with EDE diagnostic items [19] to rule out ED pathology.

All participants of the study were interviewed using the Oxford RFI [19], and all of the interviews were performed face-to-face and were conducted by clinical psychologists trained in the use of the standardized interview procedure of the EDE, SCID-I and RFI. Risk factor interviews were conducted by an assessor who was aware of the case status of the participant. To address this limitation and minimize the risk of biased assessment, interviewer bias was discussed during training and supervision, as suggested by Fairburn et al. [18].

Data analysis

Comparisons between the AN, control (PC and NC) and BN groups were performed using a logistic regression analysis (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences/SPSS version 15.0). First, we analyzed some relevant statistical assumptions previous to the regression analysis: (1) we studied the variability of each risk factor in the three participants groups excluding the risk factors that did not show variability between the groups; (2) we assessed the relative significance of different types of exposure in each subdomain and domain—individual putative risk factors and case status were first assessed by univariate analysis with each risk factor being considered as a single indicator variable and coded 0 for absence and 1 for presence (we only considered risk factors for the regression analysis if they showed statistically significant values between the groups at p < .05); (3) then, and despite having p < .05 results, we studied the cases in which cells presented a percentage higher than 20 % if the minimum expected was less than 5; (4) the multicollinearity assumption was also investigated, excluding all the predictors that showed results that were highly correlated (values ≥ .10 or VIF < 4); (5) we then organized all the domains and subdomains considering the maximum number of predictors by participants according to Stevens’s (1946) guidelines; (6) finally, we explored potential outliers that would need to be excluded from the final analysis (Zresidual outside the range −3/+3 or Cook’s <1).

To predict case status (i.e., comparisons between AN, control (PC and NC) and BN groups), we used the logistic regression analysis. Because of the number of comparisons performed, statistical significance for the risk factor subdomain and domain analysis was set at 1 % (p ≤ .01).

Results

Participants’ demographics

Participants with AN had a mean age of 20.95 ± 5.15 years, and the mean age of onset of the first ED symptom was 15.72 ± 3.17. Participants with BN had a mean age of 22.37 ± 5.75 years, and the mean age of onset of the first ED symptom was 14.84 ± 3.41. The diagnoses duration mean was 4.11 ± 4.19 years for AN participants, and 5.28 ± 4.93 years for BN participants. Regarding exhibition of first symptoms, the mean was 5.22 ± 4.56 years and 7.53 ± 5.40 years for AN and BN participants, respectively. Mean body mass index was 15.07 ± 1.56 for AN participants, 21.15 ± 2.19 for BN participants, 20.77 ± 2.56 for non-psychiatric control participants and 21.04 ± 2.56 for psychiatric control participants. AN parental socioeconomic distribution was as follows: high (33, 33.7 %), middle (33, 33.7 %), and low (32, 32.7 %). Parental socioeconomic distribution for BN participants was: high (23, 29.1 %), middle (25, 31.6 %), and low (31, 39.2 %). The results were similar after participants from both control groups were individually matched to AN participants based on age and parental socioeconomic status (see Table 1).

Risk factors in AN versus bulimia nervosa group

Table 2 presents the distribution of putative risk factors in the AN versus BN, AN versus NC, and AN versus PC groups and the results of logistic regression analyses. Table 3 presents the overall level of exposure in each subdomain for these groups. Both tables summarize the results of the comparisons of the AN group with the BN, NC and PC groups.

Compared to the BN group, participants with AN reported significantly greater levels of exposure to all but one of the 16 subdomains (i.e., sexual, physical and psychological abuse; see Table 3).

Concerning the individual risk factors, the BN group reported significantly greater levels of exposure than the AN group to four risk factors: paternal high expectations, excessive importance about fitness/keeping in shape given by family, negative consequences because of adolescent overweight and adolescent objective overweight (all p ≤ .01; 2.25 ≤ OR ≤ 3.58; see Table 2).

AN versus non-psychiatric disorder control group

Compared to the NC group, participants with AN reported significantly greater levels of exposure to all except 1 of the 17 subdomains (i.e., behavioral problems; see Table 3). A greater degree of exposure within each subdomain/domain was associated with a greater risk of developing AN. The AN participants reported significantly greater levels of exposure in regard to perfectionism, self-consciousness about appearance, unresolved/unaddressed family disagreements, teasing, parental comments about eating, negative attitudes toward parents shape and weight, feeling fat with significant concern, being teased by peers about shape, weight, eating, and appearance, having a family history of AN or BN and antecedent life events (all p ≤ .01; 2.43 ≤ OR ≤ 3.92; see Table 2).

AN versus psychiatric control group

Compared to the PC group, participants with AN reported significantly greater levels of exposure to all but two of the 15 subdomains (i.e., parental relationship and father–daughter relationship; see Table 3). A greater degree of exposure within each subdomain/domain was again associated with a greater risk of developing AN. The AN group reported significantly greater levels of exposure than the PC group to eight risk factors: perfectionism, self-consciousness about appearance, unresolved/unaddressed family disagreements, teasing, negative attitudes toward parents’ shape and weight, significant concern about feeling fat, a family history of AN or BN and antecedent life events (all p ≤ .01; OR ≤ 3.94; see Table 2).

Discussion

When comparing AN versus BN, we found four retrospective correlates that distinguished AN participants from BN participants: paternal high expectations, family excessive importance about fitness/keeping in shape, adolescent objective overweight and negative consequences because of adolescent overweight. All were associated with the highest risk for BN development. As mentioned earlier, in the case–control study that compared AN risk factors with BN risk factors and two control groups, Fairburn et al. [18] concluded that women who developed BN seem to be vulnerable to become heavier than peers which, in addition to social consequences and some other retrospective correlates such as parental obesity and early menarche, encourage dieting. Considering our results, we further strengthen Fairburn’s results about being overweight during a critical developmental period: adolescence. Compared to AN, BN participants seem to be prone to have a development environmental context marked by high expectations, excessive importance of keeping in shape, and all factors combined with overweight have negative consequences on the individual. This picture may predispose adolescents to engage in diets. Diet is commonly one of the first symptoms in AN and BN, and there are various ED risk pathways. We should consider that these results are consistent with risk factors implicated in the onset of threshold, subthreshold and partial ED. Stice et al. [33] found that body dissatisfaction was the strongest predictor of risk in the onset of any ED, with risk being amplified by depressive symptoms. As the authors commented, increasing the effectiveness of prevention programs that target qualitatively distinct risk groups, rather than only individuals with a single risk factor, may be a possible solution. In defining community high-risk groups that may benefit from prevention programs that cover the ED risk spectrum, all etiology factors that are relevant to prevent ED onset should be anticipated.

Because AN retrospective correlates were already presented and discussed in a previous study [24], we focused on AN versus BN comparisons. Briefly, in terms of specific retrospective correlates for AN, we determined that perfectionism, participant’s self-consciousness regarding appearance, unresolved family disagreements, teasing, negative attitudes regarding parents’ shape and weight, feeling fat, a family history of ED and antecedent life events were associated with the highest risk for AN. Moreover, parental comments about eating and being teased (specifically related to shape, weight, eating, and/or appearance) emerged as retrospective correlates for general psychopathology. These results are consistent with previous research in which general retrospective correlates have been discussed in relation to specific retrospective correlates for AN development [18, 19, 22, 24]. Perfectionism and family history of ED seem to be central in the understanding of AN etiology, specifically if associated with other factors that increase the vulnerability for dieting (such as being self-consciousness about appearance and feeling fat). Prospective studies to confirm this hypothesis are needed.

Putting together the results obtained about AN vs. BN participants and AN vs. NC and PC groups we seem to have two potential pathways of risk. For AN development we confirmed perfectionism and ED in family and for BN, when compared with AN participants, we sustained being overweight during adolescence with negative consequences. Both sets of risk factors placed young women at risk to engage in diets. Commonly, diet is one of the first symptoms for AN and BN despite the confirmed presence of distinct risk factors between both ED.

Moreover, the discussed risk factors were determined by all female participants, and could be different for males, who also exhibit ED but are underrepresented in the literature.

As we already reflected [24], the current study has several limitations. The most important limitation is inherent in retrospective case–control designs, namely potential biases associated with recall. Although we made every effort to maximize the accuracy of recall, bias is unavoidable. We did not involve other informants, such as relatives or significant others, and the methodology concerning family issues was based on family history reported by the participants who were being evaluated (in contrast to a family study design [20].

However, the convergence of our findings with previous reports on the clarification of the specificity of AN risk factors [18, 22, 34], in addition to the differences between AN and BN risk pathways, clarifies the characteristics that should be considered in targeting high-risk groups and improve the effectiveness of tailored prevention programs for ED and their specific pathology.

References

Attia E, Walsh BT (2007) Anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 164:1805–1810. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071151

Bulik CM, Landt MC, van Furth EF, Sullivan PF (2007) The genetics of anorexia nervosa. Annu Rev Nutr 27:263–275. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093713

Smink FRE, Hoeken DV, Hoek HW (2012) Epidemiology of eating disorders: incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Curr Psychiatry Rep 14:406–414. doi:10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y

Keski-Rahkonen A, Hoek HW, Susser ES, Linna MS, Silova E, Raevuori A et al (2007) Epidemiology and course of anorexia nervosa in the community. Am J Psychiatry 164:1259–1265. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06081388

Wilson TG, Grilo CM, Vitousek KM (2007) Psychological treatments of eating disorders. Am Psychol 62:199–216. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199

Fairburn CG (2008) Eating disorders: The transdiagnostic view and the cognitive behavioural therapy. In: Fairburn CG (ed) Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: The Guilford Press pp 7–22. doi: 10.1177/13591045090140031012

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R (2003) Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther 41:509–528. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00088-8

Fairburn CG, Harrison PJ (2003) Eating disorders. Lancet 361:407–416. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12378-1

Bulik CM, Reba L, Siega-Riz AM, Reichborn-Kjennerud T (2005) Anorexia nervosa: definition, epidemiology, and cycle of risk. Int J Eat Disord 37:S2–S9. doi:10.1002/eat.20107

Garfinkel PE, Dorian BJ (2001) Improving understanding and care for the eating disorders. In: Striegel-Moore RH, Smolak L (eds) Eating disorders: innovative directions in research and practice. Washington: American Psychological Association/APA, pp 9–26. doi: 10.1037/10403-001

Hoek HW (2006) Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 19:289–394. doi:10.1097/01.yco.0000228759.95237.78

Striegel-Moore RH, Bulik CM (2007) Risk factors for eating disorders. Am Psychol 62:181–198. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.181

Sullivan PF (2002) Course and outcome of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (2th ed). In: Fairburn CG, Brownell KD (eds) Eating disorders and obesity: a comprehensive handbook. New York: The Guilford Press, pp 226–232. doi: 10.1080/1363849031000149756-3

Birmingham CL, Su J, Hlynsky JA, Goldner EM, Gao M (2005) The mortality rate from anorexia disorder. Int J Eat Disord 38:143–146. doi:10.1002/eat.20164

Collier DA, Treasure JL (2004) The aetiology of eating disorders. Br J Psychiatry 185:363–365. doi:10.1192/bjp.185.5.363

Treasure J, Claudino AM, Zucker N (2010) Eating disorders. Lancet 2010(375):583–593. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61748-7

Schmidt U (2002) Risk factors for eating disorders (2nd ed). In: Fairburn CG, Brownell KD (eds). Eating disorders and obesity: a comprehensive handbook. New York: The Guilford Press 2002, pp 247–250. doi: 10.1080/1363849031000149756-3

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, Welch SL (1999) Risk factors for anorexia nervosa: three integrated case-control comparisons. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56:468–476. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.55.5.425

Fairburn CG, Welch SL, Doll HA, Davies BA, O’Connor ME (1997) Risk factors for bulimia nervosa: a community based case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54:509–517. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830180015003

Jacobi C, Haywar C, de Zwaan M, Kraemer HC, Agras WS (2004) Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychol Bull 130:19–65. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.19

Karwautz A, Rabe-Heskeht S, Hu X, Zaho J, Sham P, Collier DA et al (2001) Individual-specific risk factors for anorexia nervosa: a pilot study using discordant sister-pair design. Psychol Med 31:317–329. doi:10.1017/S0033291701003129

Pike KM, Hilbert A, Wilfley DE, Fairburn CG, Dohm FA, Walsh BT et al (2008) Toward an understanding of risk factors for anorexia nervosa: a case-control study. Psychol Med 38:1443–1453. doi:10.1017/S0033291707002310

Karwautz AF, Wagner G, Waldherr K, Nader IW, Fernandez-Aranda F, Estivill X et al (2011) Gene-environment interaction in anorexia nervosa: relevance of non-shared environment and the serotonin transporter gene. Mol Psychiatry 16:590–592. doi:10.1038/mp.2010.125

Machado BC, Gonçalves S, Martins C, Hoek HW, Machado PP (2014) Risk factors and antecedent life events in the development of anorexia nervosa: a portuguese case-control study. Eur Eat Disorders Rev 22:243–251. doi:10.1002/erv.2286

Day J, Schmidt U, Collier D, Perkins S, Van den Eynde F, Treasure J et al (2011) Risk factors, correlates, and markers in early-onset bulimia nervosa and EDNOS. Int J Eat Disord 44:287–294. doi:10.1002/eat.20803

Gonçalves S, Machado BC, Martins C, Hoek HW, Machado PP. Retrospective correlates of Bulimia Nervosa: a matched case–control study (submitted)

Hilbert A, Pike KM, Goldschmidt AB, Wilfley DE, Fairburn CG, Dohm F et al (2014) Risk factors across the eating disorders. Psychiatry Res 220:500–506. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.054

American Psychiatry Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2004. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035765

First MB, Sptizer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1995. doi: 10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp351

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z (1993) The eating disorder examination (12th ed). In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT (eds) Binge Eating: nature, assessment and treatment. New York: The Guilford Press, pp 317–360. doi: 10.1002/erv.2400030211

Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ (1994) Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord 4:363–370. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199412)

Graffar M (1956) Une méthode de classification sociale d’échantillons de population. Courrier 6:445–459. doi:10.2307/2172077

Stice E, Marti CN, Durant S (2011) Risk factors for onset of eating disorders: evidence of multiple risk pathways from an 8-year prospective study. Behav Res Ther 49:622–627. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.009

Wade TD, Tiggemann M, Bulik CM, Fairburn CG, FMedSci Wray NR et al (2008) Shared temperament risk factors for anorexia nervosa: a twin study. Psychosom Med 70:239–244. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815c40f1

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by a Portuguese Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia/Foundation for Science and Technology research grant to the last author (PTDC/PSI-PCL/099981/2008) and a doctoral grant to the first author (FCT-SFRH/BD/22038/2005). The authors acknowledge Christopher G. Fairburn, MD, of the Department of Psychiatry at Oxford University (UK) for providing initial consultation and training and Helen A. Doll, PhD, for help with the initial data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board and conformed to both Portuguese and European regulations on conducting research with human participants and on the management of personal data.

Informed consent

All participants gave written informed consent, and in the case of minors, child assent and parental consent for research participation were obtained.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Machado, B.C., Gonçalves, S.F., Martins, C. et al. Anorexia nervosa versus bulimia nervosa: differences based on retrospective correlates in a case–control study. Eat Weight Disord 21, 185–197 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0236-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0236-6