Abstract

Aim

Our aim was to identify psychological and behavioral characteristics of women affected by normal weight obese (NWO) syndrome.

Methods

Anthropometric, body composition, eating behavior and physical activity were evaluated in 79 women.

Results

48.10 % of the subjects were found to be normalweight obese (NWO), 22.79 % normalweight lean (NWL), and 29.11 % pre-obese-obese (PreOB/OB) according to BMI and body composition. Significant differences (p < 0.001) among the groups were identified on analysis of the subscales of the Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2), suggesting progressively increased presence of psychopathology relative to body composition. In a further analysis, results of the subscales of the EDI-2 were compared with body composition parameters, revealing that BMI co-varied with body composition variables and psychological responses. %TBFat co-varied exclusively with body composition variables (height, weight, BMI, KgTBFat, and a decrease of KgTBLean (R 2 = 0.96; Q 2 = 0.94). The NWO was discriminated from PreOB/OB group (compared to BMI) only on the basis of body composition variables (R 2 = 0.68; Q 2 = 0.60).

Conclusion

NWO women appeared to find themselves at a cognitive crossroads, attaining intermediate scores on the EDI-2 between normal weight lean women and pre-obese or obese women, in particular in terms of drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction. The NWO syndrome not only conveys an increased risk of cardiovascular and metabolic disease, but may also significantly overlap with other eating disorders in terms of psychological symptomatology, the correct identification of which may be the key in the successful management of these patients.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01890070

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obesity and its health-related consequences are considered a worldwide epidemic [1–3]. A number of features contribute to the pathogenesis and evolution of polygenic diet-related diseases and progression towards obesity, including social factors, diet, and lifestyle, in particular over-nutrition and sedentary behavior, as well as genetic and epigenetic predisposition [4]. In particular, high fat mass has been associated with increased risk of chronic disease, such as insulin resistance leading to type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HTN), dyslipidemia, coronary heart disease (CHD), cardiovascular disease (CVD), gallbladder disease, obstructive sleep apnea, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and some malignancies including endometrial, breast, and colon cancer. The social stigma and diminished psychological well-being of the obese are notable [5].

Pathogenic changes in quantity and distribution of fat mass, once critical values are exceeded, are at the root of obesity-related disease. We previously revealed a false-negative classification of obesity obtained through body mass index (BMI), suggesting that screening for adiposity, in terms of body fat content (BF) [6], is superior to BMI in identifying subjects at higher risk of cardio-metabolic disease [7].

In recent years, a significant body of research has documented the existence of subjects suffering from normal weight obese (NWO) syndrome [8, 9]. NWO women, despite having body weight and BMI (<25 kg/m2) values within the normal range, in reality have a precariously high TBFat percentage (≥30 %) accompanied by total body lean (TBLean) mass deficiency [10], based on a genetic predisposition [11–13].

A prevalence varying from 2 to 28 % of NWO in women in the general population has been described; however, men are scarcely affected at a less than 3 % prevalence rate [14, 15]. Early inflammation, oxidative stress and genetic predisposition characterize the NWO syndrome [16–20]. NWO women had a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome (MS) [21], cardiovascular diseases (CVD), and a 2.2-fold increased risk of CVD mortality compared with those with low TBFat [14], demonstrating the need for an updated definition of obesity based on adiposity, not on body weight [9].

Body dissatisfaction has been observed to be a risk factor for obesity and eating disorders [22] irrespective of weight [23]. The aims of this study were to identify common traits in the psychological profile between NWO and obese women, and to verify the hypothesis that NWO Syndrome may be identified on the basis of eating behavior, even before an accurate assessment of body composition is performed.

Materials and methods

Subjects

A total of 121 women at the Division of Clinical Nutrition and Nutrigenomics, Department of Biomedicine and Prevention, of University of Rome Tor Vergata, and at the “Nuova Annunziatella” Clinic, Rome [11, 12] were consecutively enrolled by phone call. At the time of enrollment, each subject underwent clinical evaluation which consisted in evaluation of body composition, biochemical analysis, and genetic analysis. Biochemical and genetic analyses were used to distinguish NWO syndrome from metabolically obese normal weight (MONW) [21], and to identify the presence of comorbidity in association with %TBFat. Only NWO and not MONW were included in the study; 79 women were eligible for the study. Between January 2013 and February 2014, repeated screening of anthropometric variables and body composition was carried out on the 79 women; on the same day, the women were individually interviewed by a psychologist, as well as completing the EDI-2 test. However, genetic analyses to classify the NWO syndrome conducted in a previous study [11, 12] were considered valid for this study and, therefore, did not require reassessment. Results of genetic testing are not shown as they are not relevant to this particular study.

Exclusion criteria included history of chronic degenerative or infectious diseases, drug or alcohol abuse. Subjects with acute diseases, severe liver, heart or kidney dysfunction, endocrine disorders (diabetes, hypo- or hyper-thyroidism), cancer or other conditions capable of altering body composition (AIDS, Paget’s, gastroenteropathies with malabsorption, neuromuscular diseases, rheumatic diseases, mild to severe cognitive impairment or disability) were excluded. All subjects denied current medication use or smoking habits.

We categorized the subjects into groups according to WHO BMI as follows: underweight < 18.5 kg/m2, normal weight 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, pre-obese 25.0–29.9 kg/m2, obese > 30 kg/m2. The subjects were further classified according to %TBFat: such that group 1 was composed of normal weight lean (NWL) women, with a BMI < 25 kg/m2 and %TBFat < 30; group 2 NWO, with a BMI < 25 kg/m2, and %TBFat ≥ 30 [10]; and group 3 pre obese–obese (PreOB/OB) women, with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 and %TBFat ≥ 30, which were classified as a single group, in full accordance with observations in prior studies that BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 and %TBFat ≥ 30 convey similar health-related risks [7].

A statement of informed consent was signed by all participants, in accordance with principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Anthropometric measurements

After a 12-h overnight fast, all subjects underwent anthropometric evaluation, according to standard methods (body weight, height, waist and hip circumferences) [24]. BMI was calculated using the formula: BMI = body weight (kg)/height (m)2.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA)

Body composition analysis was assessed by DXA (i-DXA, GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA), according to the previously described procedure, for evaluating soft tissues, i.e., TBFat and TBLean [25].

Psychodiagnostic instruments

Eating behavior was assessed using the Italian version of the Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2) [26], previously standardized in an Italian population [27]. According to Vanderheyden and Boland [28], a subscale score of drive for thinness DT >4 is considered as indicative of subjects with clinically significant eating disorders. In accordance with Rosen JC et al. [29], further to a positive score on DT, a score of body dissatisfaction (BD) > 16 and Bulimia (B) > 8 was considered diagnostic of the presence of an eating disorder.

Moreover, we arranged a session to interview subjects to achieve a more accurate diagnostic evaluation. History of developmental milestones, family and personal history account was obtained by an experienced psychiatrist and involved enquiries about relationship to significant others and family dynamics or conflicts.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and minimum and maximum.

A one-way ANOVA was carried out using SigmaPlot version 12.0, from Systat Software, Inc. (San Jose, CA, USA), and the test was performed to compare the average of the responses obtained in all three groups. The program first tests the data for normality and equal variance.

Correlation was assessed using Pearson or Spearman’s rank correlation. Partial Least Squares (PLS) was carried out with Unscrambler 9.7 software (Camo Software AS, Oslo, Norway) [30]. At the end of these procedures, the validation of residual variance was computed and reported as R 2 (coefficient of determination that indicates the goodness of fit of the regression model) or Q 2 (predicted variance). In all cases, a p value <0.05 was considered significant. Multivariate analysis was performed taking into consideration body composition variables and the 11 subscales of the EDI-2.

Results

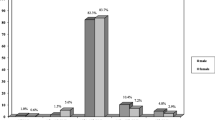

Of the 121 women initially recruited, 11 did not meet inclusion criteria, 19 dropped out of the study voluntarily and body composition data were not obtained in 12 cases, leaving a total of 79 subjects for final analysis: 18 NWL, 38 NWO, and 23 PreOB/OB. The characteristics of the study group in terms of age, weight, height, BMI and %TBFat are shown in Table 1.

There was a significant difference between the means of the three groups in terms of the responses to the subscales DT (p = 0.003), B (p < 0.001), BD (p < 0.001), Ineffectiveness (I) (p < 0.001), Interoceptive awareness (IA) (p = 0.009) and Asceticism (A) (p < 0.001) of the EDI-2 (Table 2).

A significant difference was observed between the NWO and PreOB/OB subjects in terms of DT, B, BD, IA (p < 0.05) and A (p < 0.001) and between NWL and NWO in terms of DT, B, BD, I, IA (p < 0.05) and A (p = 0.006).

A Pearson or Spearman’s rank correlation in the whole sample, to ascertain whether BMI or degree of fat mass had an influence on psychopathology, was determined (Table 3). The strongest correlations were found between BMI and scores for DT (ρ = 0.41, p = 0.0002), B (ρ = 0.48, p < 0.0001) and BD (ρ = 0.61, p < 0.0001); between %TBFat and DT (ρ = 0.35, p = 0.003), B (ρ = 0.54, p < 0.0001) and BD (ρ = 0.54, p < 0.0001); and between Wt (kg) and DT (ρ = 0.34, p = 0.002), B (ρ = 0.53, p < 0.0001) and BD (ρ = 0.51, p < 0.0001).

To investigate the presence of a relationship between psychological responses and body composition, a multivariate analysis PLS-1 was performed. With increasing BMI values, a co-variation among body composition variables and psychological responses was observed (R 2 = 0.92; Q 2 = 0.89) (Fig. 1). In particular, we observed an increase of TBFat (kg, %) and KgTBLean, along with only two psychological responses: a decrease of DT and an increase of BD. The same analysis, performed with respect of %TBFat, showed a covariation of only body composition variables; an increase of %TBFat leads to an increase of height, weight, BMI, TBFat, and to a decrease of TBLean (R 2 = 0.96; Q 2 = 0.94) (Fig. 2).

The PLS-DA, performed to discriminate NWO from PreOB/OB, showed that a discrimination between the two classes is based on only body composition variables, as %TBFat, KgTBFat, and KgTBLean (R 2 = 0.68; Q 2 = 0.60) (Fig. 3a, b).

a Discriminant analysis between NWO and PreOB/OB, related to BMI. NWO normal weight obese, PreOB/OB Pre-obese/obese, LV latent variable 1, LV2 latent variable 2. b Regression coefficients of the statistically significant variables of PLS-DA between NWO and PreOB/OB. PLS-DA partial least squares-discriminant analysis, BMI body mass index, TBFat total body fat, TBLean total body lean

Discussion

Considering that the NWO syndrome is essentially typified by the presence of a hidden yet pathologically excessive fat mass exposing the affected women to higher metabolic risk, analysis of the data obtained from this population of Italian females aimed to test the hypothesis that NWO women may have equally recondite changes on psychological evaluation, representing the subclinical manifestation of the psychopathological changes frequently observed in obese subjects. A further objective of the study was to distinguish more clearly the entity of these potential psychological characteristics both in relation to NWL and pre-obese/obese subjects.

In the present study, the cutoff points for total body fat were 30 % [31]; the analysis of anthropometric and body composition values demonstrated a frequency of 48.10 % for NWO, 22.79 % for NWL, and 29.11 % for PreOB/OB in this study population.

De Lorenzo et al. demonstrated that plasma inflammatory cytokines were significantly higher in the pre-obese/obese women and in NWO compared to a non-obese group [31]. Di Renzo et al. [19] demonstrated that NWO women were in a condition of early inflammation as well as elevated oxidative stress similar to the metabolic dysfunction associated with obesity.

Body dissatisfaction has been observed to be a risk factor for obesity and eating disorders [22] irrespective of weight [23]. It is interesting to consider that atypical depression has been linked with the presence of elevated inflammatory markers [32]. Abdominal obesity, inflammation and the metabolic syndrome are increasingly associated with psychiatric disorders [33], through several mechanisms including cytokine-mediated depletion of cerebral serotonin and dopamine, amplification of corticotropin-releasing hormone secretion, glucocorticoid resistance and increased oxidative stress, factors which may be modulated by diet and exercise.

Given the link between body composition and the risk of psychiatric illness, it seemed important to investigate the eating behavior of the NWO. Factors which lead to eventual overweight and obesity may be related to an “eating disorder attitude” [34], that is the low self-esteem, poor coping skills and unrealistic ideals and goals in terms of body shape which are associated with developing disturbed eating patterns. Furthermore, a significant correlation has been found between body dissatisfaction and weight, BMI, waist circumference and fat mass in a sample of normal weight (mean BMI 22.6 kg/m2) adolescent girls [35]. This is interesting given that NWO women have also been found to have indexes of cardiovascular risk and levels of inflammatory cytokines tending towards the obese state [8].

Understanding obesity’s heterogeneous nature is a difficult task, which involves investigating the roles of metabolic, body composition, cardiovascular disease risk as well as psychological components, in subtypes of obesity. Of significance, we observed that as BMI and body fat increased, so too did the scores of the DT, BD, I, IA and A subscales. NWO women, however, appeared to find themselves at a cognitive crossroads, scoring in the intermediate range between normal weight lean women and pre-obese or obese women on the EDI-2, particularly in terms of body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness. This observation may be tentatively attributed to an awareness on the part of NWO women of the pathological fat mass changes occurring within, perhaps provoking an adaptive behavioral response. During the individual psychological evaluation, it became apparent that NWO women displayed a distinct rigidity and internal conflict which differed from the impulsivity and alexithymia observed in the pre-obese/obese subjects. This latter trait is defined as a difficulty in recognizing and verbally expressing emotional states adequately, a notably diminished level of imagination, and a lack of ability to experience emotions completely, particularly on an interpersonal level. Furthermore, multivariate analysis revealed that as TBfat (kg, %) and weight increase, so too did BD, but interestingly DT diminished. It is as if rigid defense mechanisms are worn down over time as body total and fat mass increase to reveal the suppressed vocation for obesity. This provides initial evidence of a psychological basis for the progression from NWO to the obese state.

This information will eventually be invaluable in helping us to develop a greater understanding of the NWO syndrome and the overlap with other eating disorders in terms of psychological traits, the correct identification of which may be the key in the successful management of these patients.

An important limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size. However, it was large enough to provide us with adequate statistical power as the associations reached statistical significance despite limited sample size. Therefore, it may be considered as valid with a reasonable possibility of being reproducible in larger samples.

Our data provide the basis for further research investigating psychological predisposing and perpetuating factors in the NWO syndrome, so as to implement psychological interventions aimed at developing effective therapeutic strategies for those affected by NWO syndrome.

Given the complex etiology and repercussions on both physical and mental health of the weight, inflammation, body dissatisfaction continuum, identifying at-risk subjects such as NWO women and implementing early preventative strategies appears to be of urgent importance. Inclusion of a psychometric and eating behavior evaluation and psychotherapeutic strategies to counter disturbed dietary patterns and reinforce a healthy lifestyle may greatly improve outcomes.

References

WHO (1998) Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report on a WHO Consultation of Obesity

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL (2012) Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA 307:491–497. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.39

Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford E, Narayan KM, Giles WH, Vinicor F, Deedwania PC (2004) Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes: emerging epidemics and their cardiovascular implications. Cardiol Clin 22(4):485–504. doi:10.1016/j.ccl.2004.06.005

Dixon JB (2010) The effect of obesity on health outcomes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 316:104–108. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2009.07.008

Report of a WHO consultation (2000) Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 894:i–xii, 1–253

De Lorenzo A, Nardi A, Iacopino L, Domino E, Murdolo G, Gavrila C, Minella D, Scapagnini G, Di Renzo L (2014) A new predictive equation for evaluating women body fat percentage and obesity-related cardiovascular disease risk. J Endocrinol Invest 37(6):511–524. doi:10.1007/s40618-013-0048-3

De Lorenzo A, Bianchi A, Maroni P, Iannarelli A, Di Daniele N, Iacopino L, Di Renzo L (2013) Adiposity rather than BMI determines metabolic risk. Int J Cardiol 166(1):111–117. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.10.006

De Lorenzo A, Martinoli R, Vaia F, Di Renzo L (2006) Normal weight obese (NWO) women: an evaluation of candidate new syndrome. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 16(8):513–523. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2005.10.010

Oliveros E, Somers VK, Sochor O, Goel K, Lopez-Jimenez F (2014) The concept of normal weight obesity. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 56(4):426–433. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2013.10.003

Di Renzo L, Del Gobbo V, Bigioni M, Premrov MG, Cianci R, De Lorenzo A (2006) Body composition analyses in normal weight obese women. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 10(4):191–196

Di Renzo L, Sarlo F, Petramala L, Iacopino L, Monteleone G, Colica C, De Lorenzo A (2013) Association between -308 G/A TNF-α polymorphism and appendicular skeletal muscle mass index as a marker of sarcopenia in normal weight obese syndrome. Dis Markers 35(6):615–623. doi:10.1155/2013/983424

Di Renzo L, Gratteri S, Sarlo F, Cabibbo A, Colica C, De Lorenzo A (2014) Individually tailored screening of susceptibility to sarcopenia using p53 codon 72 polymorphism, phenotypes, and conventional risk factors. Dis Markers. doi:10.1155/2014/743634

Di Renzo L, Marsella L, Sarlo F, Soldati L, Gratteri S, Abenavoli L, De Lorenzo A (2014) C677T gene polymorphism of MTHFR and metabolic syndrome: response to dietary intervention. J Transl Med 12:329. doi:10.1186/s12967-014-0329-4

Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, Korenfeld Y, Boarin S, Korinek J, Jensen MD, Parati G, Lopez-Jimenez F (2010) Normal weight obesity: a risk factor for cardiometabolic dysregulation and cardiovascular mortality. Eur Heart J 31(6):737–746. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp487

Marques-Vidal P, Pécoud A, Hayoz D, Paccaud F, Mooser V, Waeber G, Vollenweider P (2008) Prevalence of normal weight obesity in Switzerland: effect of various definitions. Eur J Nutr 47(5):251–257. doi:10.1007/s00394-008-0719-6

Di Renzo L, Bigioni M, Bottini FG, Del Gobbo V, Premrov MG, Cianci R, De Lorenzo A (2006) Normal Weight Obese syndrome: role of single nucleotide polymorphism of IL-15R-alpha and MTHFR 677CT genes in the relationship between body composition and resting metabolic rate. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 10(5):235–245. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2006.11.002

Di Renzo L, Bigioni M, Del Gobbo V, Premrov MG, Barbini U, Di Lorenzo N, De Lorenzo A (2007) Interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor antagonist gene poymorphism in normal weight obese syndrome: relationship to body composition and IL-1α and β plasma levels. Pharmacol Res 55(2):131–138. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2006.11.002

Di Renzo L, Bertoli A, Bigioni M, Del Gobbo V, Premrov MG, Calabrese V, Di Daniele N, De Lorenzo A (2008) Body composition and -174 G/C Interleukin-6 promoter gene polymorphism: association with progression of insulin resistance in normal weight obese syndrome. Curr Pharm Des 14:2699–2706. doi:10.2174/138161208786264061

Di Renzo L, Galvano F, Orlandi C, Bianchi A, Di Giacomo C, La Fauci L, Acquaviva R, De Lorenzo A (2010) Oxidative stress in normal-weight obese syndrome. Obes (Silver Spring). 18(11):2125–2130. doi:10.1038/oby.2010.50

Kang S, Kyung C, Park JS, Kim S, Lee SP, Kim MK, Kim HK, Kim KR, Jeon TJ, Ahn CW (2014) Subclinical vascular inflammation in subjects with normal weight obesity and its association with body Fat: an 18 F-FDG-PET/CT study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 13(1):70. doi:10.1186/1475-2840-13-70

Madeira FB, Silva AA, Veloso HF, Goldani MZ, Kac G, Cardoso VC, Bettiol H, Barbieri MA (2013) Normal weight obesity is associated with metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance in young adults from a middle-income country. PLoS One 8(3):e60673. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060673

Haines J, Neumark-Sztainer D (2006) Prevention of obesity and eating disorders: a consideration of shared risk factors. Health Educ Res 21(6):770–782. doi:10.1093/her/cyl094

Villarejo C, Jiménez-Murcia S, Álvarez-Moya E et al (2014) Loss of control over eating: a description of the eating disorder/obesity spectrum in women. Eur Eat Disord Rev 22(1):25–31. doi:10.1002/erv.2267

Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R (1998) Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Champaign, IL, Human Kinetics

Hansen RD, Raja C, Aslani A, Smith RC, Allen BJ (1999) Determination of skeletal muscle and fat-free mass by nuclear and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry methods in men and women aged 51–84 years (1–3). Am J Clin Nutr 70:228–233

Garner DM (1991) Eating disorder inventory-2 professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa

Rizzardi M, Trombini G (1995) EDI-2. Organizzazioni Speciali, Firenze

Vanderheyden DA, Boland MA (1987) A comparison of normals, mild, moderate, and severe binge eaters, and binge vomiters using discriminant function analysis. Int J Eat Disord 6(3):331–337. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(198705)6:3<331::AID-EAT2260060302>3.0.CO;2-M

Rosen JC, Gross J, Vara L (1987) Psychological adjustment of adolescents attempting to lose or gain weight. J Consult Clin Psych 55(5):742–747. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.55.5.742

Martens HA, Anderssen E, Flatberg A, Gidskehaug LH, Høy M, Westad F, Thybo A, Martens M (2005) Regression of a data matrix on descriptors of both its rows and of its columns via latent variables: L-PLSR. Comput Stat Data Ana l48(1):103–123

De Lorenzo A, Del Gobbo V, Premrov MG, Bigioni M, Galvano F, Di Renzo L (2007) Normal-weight obese syndrome: early inflammation? Am J Clin Nutr 85:40–45

Lasserre AM, Glaus J, Vandeleur CL, Marques-Vidal P, Vaucher J, Bastardot F, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Preisig M (2014) Depression with atypical features and increase in obesity, body mass index, waist circumference, and fat mass. JAMA Psychiatry 71(8):880–888. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.411

Rosenblat JD, Cha DS, Mansur RB, McIntyre RS (2014) Inflamed moods: a review of the interactions between inflammation and mood disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 53C:23–34. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.01.013

Ramacciotti CE, Coli E, Bondi E, Burgalassi A, Massimetti G, Dell’osso L (2008) Shared psychopathology in obese subjects with and without binge-eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 41(7):643–649. doi:10.1002/eat.20544

Boschi V, Siervo M, D’Orsi P, Margiotta N, Trapanese E, Basile F, Nasti G, Papa A, Bellini O, Falconi C (2003) Body composition, eating behaviour, food-body concerns and eating disorders in adloescent girls. Ann Nutr Metab 47:284–293. doi:10.1159/000072401

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to all the subjects who volunteered in the study.

This study was supported by grants from Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Forestry (D.M.; 2017188).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures of the study were performed in accordance with the1964 Helsinki declaration.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Di Renzo, L., Tyndall, E., Gualtieri, P. et al. Association of body composition and eating behavior in the normal weight obese syndrome. Eat Weight Disord 21, 99–106 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0215-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0215-y