Abstract

Purpose

Recent studies have shown that body image perception is an important factor in weight management and can be influenced by several social or cultural factors in Western or non-Western societies; however, body image perception and its nutritional and demographic determinants in Iran have not been extensively studied. In the current study, we aimed to evaluate body image perception and its socio-demographic and nutritional determinants among female university students in Tabriz City of Iran.

Methods

In the current cross-sectional survey, 184 female students aged 18–35 years from Tabriz, Iran, were enrolled. Anthropometric variables including weight, height, waist and hip circumference were measured and body mass index (BMI) and waist to hip ratio (WHR) were calculated. Body image perception and distortion were assessed by Figure Rating Scale (FRS) developed by Stunkard consisting of nine silhouettes. Nutrition intake was assessed by a 3-day 24-h dietary recall method and analyzed by Nutritionist IV software.

Results

Most of the participants in the underweight (41.66 %), normal weight (67.71 %) and overweight (57.14 %) categories of BMI selected the thinnest figure as their desirable or ideal body image perception. The total prevalences of body image dissatisfaction and distortion were 51.63 % and 64.13 %, respectively. Subjects who had undistorted body image perception consumed more time for physical activity and had more night sleeping hours compared with others (P < 0.05). Subjects who perceived themselves as being of normal weight had significantly lower intake of total fat and saturated fatty acids and higher intakes of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) compared with other groups (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

According to our findings, female participants had a higher tendency to consider thinness as the preferred body image style. Persons with undistorted body image perception had healthy nutritional status compared with others. Due to high prevalence of body image dissatisfaction, the need for appropriate interventional programs to prevent the associated co-morbidities is emphasized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Body image has been defined as “a person’s perceptions, thoughts and feelings about his or her body” by Grogan [1] and there is an increasing focus on it in developed and developing societies. Body image perceptions depend to numerous factors including socio-cultural influences, psychological factors and demographic characteristics [2]. Biological variables including age, race and ethnicity, gender, anthropometric variables and mass media can all influence body image perceptions [3, 4]. Body image dissatisfaction and distortion defined, respectively, as being dissatisfied with current body shape and having an unrealistic view of how someone sees his or her body [1] are negatively associated with happiness in life [5]. Body image dissatisfaction is an important risk factor for eating disorders, low self-esteem and depressive disorders such as chronic dysphoria [6, 7]. Considering these co-morbidities of body image dissatisfaction and distortion, it is important to assess and reduce the risk of these problems in the society. Numerous evidences suggest that women suffer more than men from body image dissatisfaction regardless of their age and this discontentment negatively impacts their life [8]. Women are more likely than men to describe themselves as fat, to weigh themselves often and to diet more frequently than men [9, 10].

Although it is generally believed that body image dissatisfaction and their co-morbidities are a Westernized society problem, it is obviously clear that this phenomenon is also increasing toward other cultures and diverse communities [11]. In Western societies, thinness is associated with self-control, elegance and youthfulness and women of higher socioeconomic groups are less likely to be obese [12]. Several studies in developing countries have also reported higher desire to be thin across different socio-cultural environments [12–14], while several others have identified results in different directions and being overweight but not obese was the desirable body weight perception [15]. Urbanization and exposure to media have extreme effects on body image perceptions in developing countries. In Iran, previous studies evaluated the relationship between body image perceptions and its socio-demographic determinants; Omidvar et al. [16] found higher prevalence of body image dissatisfaction among female adolescents in Tehran. Another study by Novin et al. [17] among university personnel reported a negative relation between body image satisfaction and body mass index. Although several studies have been carried out in this field, it is important to proceed further in this direction to better understand the many facets of the concepts of body image and its perception. Particularly, it is necessary to evaluate body image dissatisfaction in relation to nutrient intake and energy consumption for better presentation of this problem. Previous observations have suggested the effects of body image perceptions on food intake and nutritional behaviors; Neumark-Sztainer et al. [18] found that a lower body image satisfaction was related to lower intake of fruits and vegetables. In another report by Harper et al. [19], female college students with satisfied body size perceptions were more likely to have healthy dietary choices and higher physical activity. Change in lifestyle and having more physical activity had been associated with improvements in body image satisfaction during obesity treatment programs in women [20]. Several reports have also suggested the possible role of marital status on body image perceptions; Manos reported that married women had a more positive body image than non-married women [21].

Our review of literature found no report evaluating the body image perception and its association with nutrient intakes or socio-demographic factors in Iran. Therefore in the current study, we aimed to evaluate body image perception and its social, demographic and nutritional determinants among female university students in Tabriz.

Methods

Participants

A cross-sectional survey was conducted on 184 female volunteer students aged 18–35 years from Tabriz University of Medical Sciences from April to July 2014. Socio-demographic data were gathered using a questionnaire including information about age, educational attainment, parents’ educational level, marital status and family size. The subjects were also asked about how much time they spend for exercise per week. They also reported the total hours of sleeping during night and day. Subjects were screened for having eating disorders including anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa according to Diagnostic and Statistics Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition-text revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria prior participation in the study and patients with eating disorders were excluded [22].

Anthropometric assessments

Anthropometric measurements were taken by trained technicians according to standard procedures; weight was measured to nearest 0.1 kg with a high-precision mechanical scale and height was recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm with a stadiometer. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m). Waist circumference (WC) was measured in horizontal plane in centimeters, midway between the lowest rib and the iliac crest with a measuring tape. Waist to hip ratio (WHR) was calculated from waist circumference divided by hip circumference. Participants were divided as underweight, normal weight, overweight and obese when their BMI were <18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25–29.9 and ≥30 kg/m2 [23].

Body image perceptions

Body image perception was assessed by Figure Rating Scale (FRS) developed by Stunkard et al. [24]. Figure Rating Scale consisted of nine silhouettes presenting body shape image ranging from 1 to 9 where 1 is the thinnest body type and 9 the largest, most obese type (Fig. 1). Subjects were asked to mark the figure they resemble (perceived body size) and then the figure they would want to look like (ideal body size). Body size satisfaction was examined through the difference between perceived and ideal body sizes. Scores of zero indicate body size satisfaction and negative or positive scores indicate body image dissatisfaction, while negative scores indicate desire to gain weight and positive scores indicate desire to lose weight. Body image distortion was also examined through the difference between perceived body image and actual body size based on BMI categories. Scores of zero indicate body image undistortion, while negative or positive scores indicate body image distortion.

Body image figures (Stunkard et al. [24]). This figure was copyrighted by Albert Stunkard (reproduced with kind permission). The body image figures have been ordered by size and assigned values of 1 through 9

The numbers on the scale of body image perceptions (perceived or ideal) were also classified according to standard procedure [25, 26] into four groups: 1 and 2 underweight; 3 and 4 normal weight; 5–7 overweight; and 8 and 9 obese shape.

Dietary information

Dietary information was assessed by a 3-day 24-h dietary recall method. Dietary intake of energy, macronutrients and micronutrients was analyzed by Nutritionist IV software.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 18. Data were presented as mean ± SD or number and percentages. The comparison of continuous variables including age, night and day sleeping hours and physical activity level among two independent groups was performed by Student’s t test. Comparison of dietary intakes between different classifications of perceived body image was conducted by one-way ANOVA using Tukey’s post hoc analysis for between-group comparisons. Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to compare educational attainment or marital status between different groups of body size satisfaction or to compare body mass index categories in different perceived body image groups. P values less than 0.05 were considered as significant.

Results

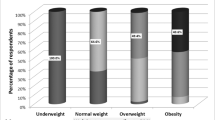

The total sample of 184 female university students of mean age 22.16 ± 2.19 years were recruited in the current study. Most of the students were from Bachelor of Science (BS) degree (≈85 %) and their mean BMI was 22.19 ± 3.40 kg/m2 (Table 1). Table 2 presents the distribution of participants by perception of body image classification; 35.86 % of the total participants had correct body image perception according to BMI classifications. Most of the participants in underweight (41.66 %), normal weight (67.71 %) and overweight (57.14 %) categories of BMI selected the thinnest Fig. 1(2) as their desirable or ideal body image perception (Table 3).

The total prevalence of body image dissatisfaction was 51.63 %, while approximately 28.73 % of them obtained positive scores (had desire to be thinner). The comparisons of demographic characteristics in different groups of body image distortion and body image satisfaction are shown in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. Subjects who had undistorted body image perceptions expended more time on physical activity and had more night sleeping and less day sleeping hours compared with subjects who had distorted body image perceptions (Table 4; P < 0.05). Similar comparisons were also performed between different groups of body image satisfaction, although no significant difference was achieved (Table 5).

Mean energy and nutrient intakes according to classifications of perceived body image are shown in Table 6. Subjects who perceived themselves as being of normal weight had significantly lower intake of total fat and saturated fatty acids and higher intakes of monounsaturated fatty acids compared with other groups (P < 0.05). Mean energy and carbohydrate intake in persons with normal weight perceived body image perception were non-significantly lower than in other groups (P > 0.05).

Discussion

The current study determined perceived and ideal body image perceptions in relation to body mass index and nutritional status among female university students in Tabriz, Iran. According to the review of literature, the university population is regarded as a convenient sample for the study of health in young adults [27]. The comparisons between ideal figure and perceived figure in females showed that thinness was the most desirable body image among female participants. The total prevalences of underweight and overweight or obesity in this sample were 13.04 and 17.93 %, respectively. In Western societies, thinness is desirable and women of higher socioeconomic groups are less likely to be obese [12]. Zaccagni et al. [28] reported a higher desire for thinness among university students in Italy; 81 % of these students would like to be thinner and the prevalence of body image dissatisfaction was 87 %. Similar findings were also reported among US college students [29]. However, the concern about body image conceptions in developing countries has changed in recent years. Previous concerns about body image in developing countries admired obesity and obesity was a symbol of social success and wealth in countries where economic resources were scarce [30–32]; however, exposure to mass media and diverse socio-cultural pressures in developing countries have caused an increased awareness of considering the Western “thin” as ideal and contributed to body image distortion [33]. In our study, the prevalences of body image dissatisfaction and distortion were 51.63 and 64.13 %, respectively. Of the subjects who were dissatisfied with their body image, 28.73 % desired to be thinner. Of the total participants, 53.8 % selected the thinnest figure as their desirable or ideal body image perception. Other studies in developing countries reported higher prevalence of body image dissatisfaction; for example Latha [34] reported 86 % desire for thinness among female college students in India. Another study in UAE by Thomas [35] reported 74.8 % body image dissatisfaction among female university students, while thinness was the most desirable body image preference.

In our study, the prevalence of body image dissatisfaction among married and single subjects was 42.10 and 54.10 %, respectively, which were comparable with each other and with no significant difference. This finding was in agreement of Freidman’s [36] finding reporting equal prevalence of body image dissatisfaction in single and married couples with a history of eating disorders; they also found no relationship between marital status and body image satisfaction; while low marital satisfaction was significantly associated with greater body image dissatisfaction (r = −0.32, P < 0.0001). We did not evaluate marital satisfaction in the current study.

In our study, subjects who had undistorted body image perceptions and were satisfied with their body image had higher rate of exercise and higher amount of night sleeping hours compared with subjects who had distorted body image perception and were unsatisfied with their body image. In the study by Farah [37], a negative relationship between physical activity and total body image discrepancy score was observed. These findings are not unexpected, because most of the subjects who were satisfied with their body image perception also had a good quality of life and better lifestyles compared with others.

Body image distortion is associated with unhealthy conditions such as depressive syndromes [38]; previous reports found that young girls with body image distortion were more likely to participate in unsafe weight loss programs including extreme weight loss behaviors and frequent dieting [39].

This can be further confirmed by our findings about nutrient intakes; subjects who perceived themselves as being of normal weight also had lower energy, carbohydrate and total and saturated fat intakes and higher amount of MUFA intake compared with other groups. A positive association between healthy dietary habits and normal body image perception was also observed in the study of Kargar-Novin et al. [17] and Contento et al. [40].

In conclusion, the participants of the current study chose the thinnest body image as their preferable style. Additionally, persons who perceived themselves as being of normal weight had better nutritional status and sleeping habits compared with others. Exploring these associations could help apply interventional programs to protect these individuals who are at risk of developing health problems.

References

Grogan S (2007) Body image: understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women, and children, 2nd edn. Taylor and Francis, UK, p 237

Laus MS, Miranda VPN, Almeida SS, Costa TMB, Ferreira MEC (2013) Geographic location, sex and nutritional status play an important role in body image concerns among Brazilian adolescents. J Health Psychol 18(3):332–338. doi:10.1177/1359105311434755

Banitt AA, Kaur H, Pulvers KM (2008) BMI percentiles and body image discrepancy in black and white adolescents. Obesity 16(5):987–991. doi:10.1038/oby.2008.21

Ceballos N, Czyzewska M (2010) Body image in Hispanic Latino vs. European American adolescents: implications for treatment and prevention of obesity in underserved populations. J Health Care Poor Underserved 21(3):823–838. doi:10.1353/hpu.0.0333

Reynaga-Abiko G (2011) Body image. In: Encyclopedia of women in today’s world. Stange MZ, Oyster CL, Sloan JE (ed). SAGE Publications, California, pp 170–174. doi:10.4135/9781412995962

Wardle J, Waller J, Fox E (2002) Age of onset and body dissatisfaction in obesity. Addict Behav 27:561–573. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00193-9

Rosenstram T, Jokela M, Hintsanen M, Josefsson K, Juonala M, Kivimaki M, Pulkki-Raback L, Viikari JSA, Hutri-Kahanen N, Heinonen E, Raitakari OT, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L (2013) Body-image dissatisfaction is strongly associated with chronic dysphoria. J Affective Disord 150(2):253–260. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.003

Brennan MA, Lalonde CE, Bain J (2010) Body image perceptions: do gender differences exist? Psi Chi J Undergrad Res 15(3):1089–4136

Kinlen AD (2006) Self-perceptions and body image in preadolescent girls and boys. Dissertation, Oklahoma State University

Fallon A (1990) Culture in the mirror: sociocultural determinants of body image. In: Thomas F, Pruzinsky T (eds) Body images: development, deviance, and change. Guilford Press, New York, pp 80–109

Ramberan K, Austin M, Nichols S (2006) Ethnicity, body image perception and weight-related behaviour among adolescent females attending secondary school in Trinidad. West Indian Med J 55(6):388–393. doi:10.1590/S0043-31442006000600004

Metcalf PA, Scragg RK, Willoughby P, Finau S, Tipene-Leach D (2000) Ethnic differences in perceptions of body size in middle-aged European, Maori and Pacific people living in New Zealand. Int J Obesity Relat Metab Disord 24(5):593–599

Kaviraj S, Sinha A, Chakraborty N, Roy H, Majumdar R, Mondal MM (2013) Physical activity status and body image perception of adolescent females in a slum in Kolkata. India. IOSR-JDMS 10(1):11–14

Craig P, Halavatau V, Comino E, Caterson I (1999) Perception of body size in the Tongan community: differences from and similarities to an Australian sample. Int J Obesity Relat Metab Disord 23(12):1288–1294

Holdsworth M, Gartner A, Landais E, Maire B, Delpeuch F (2004) Perceptions of healthy and desirable body size in urban Senegalese women. Int J Obesity 28(12):1561–1568. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0802739

Omidvar N, Egtesadi SH, Tabatabaei MG, Minaei S, Samareh S (2003) Body image and its relations with body mass index and dietary food consumption in Tehranian adolescences. Res Med 26(4): 257–264 (In Persian)

Kargarnovin Z, Asadi Z, Rashidkhani B, Azar M (2013) Assessing body image and its relation with body mass index, food group consumption and physical activity among the university of economic science. Iran J Endocrinol Metab 14(5):455–463 (In Persian)

Neumark-Sztainer D, Paxton SJ, Hannan PJ, Haines J, Story M (2006) Does body satisfaction matter? Five- year longitudinal associations between body satisfaction and health behaviors in adolescent females and males. J Adolesc Health 39(2):244–251. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.001

Harper L (2009) The impact of macronutrient intake on body image among Female College undergraduate students, dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Stout

Carraca EV, Markland D, Silva MN, Coutinho SR, Vieira PN, Minderico CS, Sardinha LB, Teixeira PJ (2012) Physical activity predicts changes in body image during obesity treatment in women. Med Sci Sports Exerc 44(8):1604–1612. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31824d922a

Manos D, Sebastian J, Bueno MJ, Mateos N, Torre A (2005) Body imagein relation to self-esteem in a sample of Spanish women with early-stage breast cancer. Psicooncologia 2(1):103–116

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. text rev. Washington

World Health Organization (2000) Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. WHO obesity Technical Report Series 894; World Health Organization, Genava, Switzerland

Stunkard AJ, Sorensen T, Schulsinger F (1983) Use of the Danish adoption register for the study of obesity and thinness. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis 60:115–120

Bhuiyan AR, Gustat J, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS (2003) Differences in body shape representations among young adults from a biracial (Black-White), semirural community: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Epidemiol 158(8):792–797. doi:10.1093/aje/kwg218

Lynch E, Liu K, Wei GS, Spring B, Kiefe C, Greenland P (2009) The relation between body size perception and change in body mass index over 13 years. Am J Epidemiol 169:857–866. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn412

Nojomi M, Najamabadi S (2006) Obesity among university students, Tehran. Iran. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 15(4):516–520

Zaccagni L, Masotti1S, Donati R, Mazzoni G, Gualdi-Russo E (2014) Body image and weight perceptions in relation to actual measurements by means of a new index and level of physical activity in Italian university students. J Transl Med 12: 42–50

Wharton CM, Adams T, Hampl JS (2008) Weight loss practices and body weight perceptions among US college students. J Am Coll Health 56(5):579–584. doi:10.3200/JACH.56.5.579-584

Sobal J, Stunkard AJ (1989) Socioeconomic status and obesity: a review of the literature. Psychol Bull 105:260–275

Brown PJ, Konner M (1987) An anthropological perspective on obesity. Ann NY Acad Sci 499:29–46

Paquettea MC, Raine K (2004) Sociocultural context of women’s body image. Soc Sci Med 59:1047–1058. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.016

Wykes M, Gunter B (2005) The media and body image. Sage Publications, London

Latha KS, Hegde S, Bhat SP, Rai P (2006) Body image, self-esteem and depression in female adolescent college students. J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Ment Health 2:78–84

Thomas J, Khan S, Abdulrahman AA (2010) Eating attitudes and body image concerns among female university students in the United Arab Emirates. Appetite 54(3):595–598. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2010.02.008

Friedman MA, Dixon AE, Brownell KD, Whisman MA, Wilfley DE (1999) Marital status, marital satisfaction, and body image dissatisfaction. Int J Eat Disord 26:81–85. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X07

Farah Wahida Z, Mohd Nasir MT, Hazizi AS (2011) Physical activity, eating behaviour and body image perception among young adolescents in Kuantan, Pahang Malaysia. Mal J Nutr 17(3):325–336

Blashill AJ, Wilhelm S (2014) Body image distortions, weight, and depression in adolescent boys: longitudinal trajectories into adulthood. Psychol Men Masc 15(4):445–451. doi:10.1037/a0034618

Liechty JM (2010) Body image distortion and three types of weight loss behaviors among non over weight girls in the United States. J Adolescent Health 47:176–182. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.004

Contento IR, Basch C, Zybert P (2003) Body image, weight, and food choices of Latina women and their young children. J Nutr Educ Behav 35(5):236–248. doi:10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60054-7

Acknowledgments

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alipour, B., Abbasalizad Farhangi, M., Dehghan, P. et al. Body image perception and its association with body mass index and nutrient intakes among female college students aged 18–35 years from Tabriz, Iran. Eat Weight Disord 20, 465–471 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0184-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0184-1