Abstract

Recently, several studies have pointed the importance of thought suppression as a form of experiential avoidance in different psychopathological conditions. Thought suppression may be conceptualized as an attempt to decrease or eliminate unwanted internal experiences. However, it encloses a paradoxical nature, making those thoughts hyper accessible and placing an extra burden on individuals. This avoidance process has been associated with several psychopathological conditions. However, its role in eating psychopathology remains unclear. The present study aims to explore the moderation effect of thought suppression on the associations between body image-related unwanted internal experiences (unfavorable social comparison through physical appearance and body image dissatisfaction) and eating psychopathology severity in a sample of 211 female students. Correlational analyses showed that thought suppression is associated with psychological inflexibility and eating disorders’ main risk factors and symptoms. Moreover, two independent analyses revealed that thought suppression moderates, as it amplifies, the impact of unfavorable social comparisons through physical appearance (model 1) and body image dissatisfaction (model 2) on disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Hence, for the same level of these body-related internal experiences, young females who reveal higher levels of thought suppression present higher eating psychopathology. Taken together, these findings highlight the key role of thought suppression in eating psychopathology and present important clinical implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Eating disorders are widely recognized as complex and multidetermined psychopathological conditions [1]. Literature has been highlighting the important role of body image dissatisfaction as a major risk factor in the etiology and development of eating psychopathology [e.g., 2, 3]. In fact, the perception of a significant discrepancy between the current body image and the desired one (i.e., body image dissatisfaction) has been linked to several disordered attitudes and behaviors that aim to weight and shape control (e.g., dieting) [2]. Additionally, several studies have pointed out that the perception of this discrepancy may be experienced as a social threat, putting one at risk of being ignored, criticized or rejected by others [4, 5].

In fact, physical appearance is a self-evaluative central domain for many women, regardless of their age, as it is intrinsically linked not only to beauty standards, but also to positive psychological attributes (e.g., dominance, perseverance and social competences), health, success and happiness [6–8]. Furthermore, in Western societies, presenting a thin body image (similar to the bodies presented by models or celebrities) is considered ideal as it offers several social advantages, such as positive social attention, approval and favorable appreciation from others [9–11]. These social advantages define a favorable and secure social rank [12]. In contrast, presenting a physical appearance different from the valued ones (e.g., overweight) frequently triggers unfavorable social comparisons, which in turn lead to feelings of inferiority, inadequacy and undesirability [e.g., 13]. Moreover, several studies demonstrate the central role of feelings of inferiority and inadequacy on the development of eating psychopathology [3, 11]. Nevertheless, the impact of these well-known risk factors (body image dissatisfaction and unfavorable social comparisons) in disordered eating attitudes and behaviors may be enhanced by maladaptive psychological processes.

Thought suppression can be conceptualized as an experiential avoidance strategy that involves attempts to diminish or eradicate unwanted thoughts by trying not to think about a specific topic. However, trying to suppress a thought has detrimental side effects, given that this process holds a paradoxical nature, increasing the frequency and impact of thoughts [14, 15]. Meta-analytic studies concerning the paradoxical effects of thought suppression confirm the rebound effect of this ineffective control strategy, showing that suppressed thoughts often return even more strongly [16, 17]. Furthermore, thought suppression has been consistently associated with several psychopathological conditions like depression [18], posttraumatic stress disorder [19] and obsessive–compulsive disorder [20].

Specifically, in the eating disorders field, a growing body of evidence highlights the pervasive role of experiential avoidance processes in body- and eating-related psychopathology [e.g., 21–24]. In fact, several studies have consistently showed the association between food and weight-related thought suppression and increased food intake, eating disorder symptoms, food cravings and binge-eating episodes. Specially for at-risk groups such as individuals with eating disorders, obesity or dietary restraint attitudes, food, eating and weight-related thoughts may function as warning signals (i.e., unwanted internal experiences) that tend to enhance control and suppression attempts [e.g., 25–34]. In turn, thought suppression attempts paradoxically turn food, eating and weight-related thoughts hyper accessible increasing preoccupation with food and even unsettling eating behaviors [e.g., 24, 26].

Despite all the evidence on the impact of food, eating and weight-related thought suppression on eating psychopathology, less is known on the role of the general tendency to suppress thoughts in disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Recent studies suggest that individuals that do not accept their negative emotional experiences tend to engage in thought suppression. In turn, due to the rebound effect of this mechanism, these individuals are more likely to adopt maladaptive strategies such as disordered eating behaviors to cope with their initial unsuccessful suppression efforts [21, 35].

In sum, although there is empirical evidence on the relevance of thought suppression on disordered eating, its role in this psychopathological process is yet scarcely known. Therefore, the key goal of the present paper is to explore the moderator effect of general thought suppression on the relationship between two main eating psychopathology’s risk factors (body image dissatisfaction and social comparison through physical appearance) and eating psychopathology severity in young female sample. The hypothesis that underlies this study is that thought control strategies may amplify the impact of the risk factors for disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in young females.

Materials and methods

Participants

Two-hundred and eleven female Caucasian students aged between 15 and 23 years old participated in this study. They presented a mean age of 18.57 (SD = 2.02) and of 12.29 (SD = 1.85) years of education. The average BMI was 21.41 (SD = 2.77). This young female sample was used since it is considered as a risk group for eating disorders due to the existence of high levels of body dissatisfaction and eating disordered behaviors (such as bingeing, purging, and chronic dieting) which seems to remain stable across different age cohorts [36, 37].

Procedures

The current research was presented and approved by the Ethics Committee Boards of all the educational institutions participating in the study. The female students who participated in the study were recruited from several high schools and from the University of Coimbra. All participants (and their parents, if they were underage) were required to sign a consent form to take part in the study. Participants were fully informed about the aim of the study and the confidential nature of the data before completing several self-report measures during class (approximately 15 min) in the presence of the teacher and one of the researchers. Further explanations were provided when needed. Students who did not participate were given a task by the teacher.

Measures

Demographic data

Participants were asked about their age and completed years of education. Participant’s height and weight were self-reported and then BMI (kg/m2) was calculated.

White Bear Suppression Inventory (WBSI) [38, 39]

The WBSI is a 15-item scale that assesses thought suppression using several statements which the participant has to score on a 5-point Likert Scale. Higher scores reveal increased tendencies to suppress unwanted thoughts. The scale showed good reliability both in the original study (α from .87 to .89) and in the Portuguese validation study.

Social Comparison Through Physical Appearance Scale (SCPAS) [5]

This is a self-report scale, with 12 items, that measures women’s perceptions of their social standing based on physical appearance. Participants are asked to compare themselves to others based on physical appearance, using a 10-point Likert scale with opposing constructs. It comprises two different parts. In part A, participants are asked to compare themselves to peers, and in part B with models/celebrities. For the purpose of the current study, only part B was considered. The scale was reverse scored to obtain a measure of unfavorable comparisons. Part B showed good internal consistency in the original study (α = .96).

Figure Rating Scale (FRS) [40]

The FRS consists of a series of nine silhouettes of gradually increasing sizes in accordance with their number (1—thinnest; 9—largest). The respondents are asked to indicate which of the figures corresponds to their current and desired body shape. One’s body image dissatisfaction (BD) is calculated by the discrepancy between these two figures. As shown in the original study, the FRS has adequate temporal, convergent and divergent reliabilities.

Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) [41, 42]

Developed through the EDE interview, the EDE-Q is a self-report measure that assesses eating psychopathology-related attitudes and behaviors. In the present study, only the global score of EDE-Q was used. This score was calculated through the mean of the four subscales: dietary restraint, eating concern, shape concern and weight concern. The EDE-Q showed very good levels of internal consistency, temporal reliability, and concurrent and discriminative validities [43].

The Cronbach’s alphas of all study variables are presented in Table 1.

Data analysis

Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 (IBM Corp, 2011).

To explore the association between all study variables, Pearson correlation analyses were performed [44]. Two different models were conducted to explore the moderator effect of thought suppression. In the first analysis, the moderator effect of thought suppression (WBSI) on the relationship between social comparison through physical appearance_models (SCPAS_Models) and eating psychopathology (EDE-Q) was examined. In a second analysis, the moderator effect of thought suppression on the relationship between body image dissatisfaction (BD) and EDE-Q was explored. In the analyses, BMI was controlled for and the interaction of a continuous predictor was considered [44]. A standardized procedure was used to reduce the error associated with multicollinearity. Thus, the values of the predictors (SCPAS_Models and BD) and the moderator (WBSI) were centered and the interaction product was obtained by multiplying the created variables [45]. Finally, two graphics were plotted [46] considering one curve for each of the three levels of the moderator (low, medium and high) to better understand the relationship between the independent variables (SCPAS; BD) and eating psychopathology with different levels of the moderator variable (WBSI). As recommended by Cohen et al. [44] and since there were no theoretical cut points for the moderator variable on the x axis, the three curves were plotted in the graphical representations, considering the following cut point values: one standard deviation below the mean, the mean and one standard deviation above the mean [46].

Preliminary data analyses

Firstly, the data suitability for the regression analyses was evaluated. Skewness and kurtosis values did not show a serious bias to normal distribution (SK < |3| and Ku < |8–10|) [47] and multicollinearity was not identified as all variables presented VIF values <5, which indicated the absence of β estimation problems. Additionally, independence of errors was analyzed through graphic analyses and the value of Durbin–Watson (values ranged between 1.622 and 1.739). Overall, these data were considered adequate for regression analyses.

Results

Descriptives

Means and standard deviations for the study variables are presented in Table 1.

Correlations

Pearson product-moment correlations between studied variables are presented in Table 1. Results showed that thought suppression is positively and moderately associated with unfavorable social comparisons based on physical appearance (SCPAS_Models) and eating psychopathology severity (EDE-Q global score). It also presented a positive association, although weak, with body dissatisfaction. In turn, no significant correlation was found between thought suppression and BMI. Partial correlation analyses were performed controlling for age, and results showed the same pattern and magnitude of the associations between all study’s variables. Therefore, age was not considered in the further analyses.

Moderation analyses

Given the previous findings and to further understand the role of thought suppression in eating psychopathology severity, two moderator analyses were conducted. It was explored whether thought suppression (WBSI) moderated the relationship of unfavorable social comparisons based on physical appearance (SCPAS_Models; Model 1) and body image dissatisfaction (BD; Model 2) with disordered eating symptoms (EDE-Q). To control for BMI, this variable was entered in the first step of each model, as it showed significant correlations with BD, SCPAS_Models and EDE-Q.

-

1.

The moderator effect of thought suppression on the relationship between unfavorable social comparisons based on physical appearance and eating psychopathology

Firstly, BMI and SCPAS_Models were entered as predictors in the first step of the regression model (Table 2). On the next step, WBSI was further included as a predictor variable. In both steps of the regression analysis, statistically significant models were obtained [Step 1: R 2 = .27, F (2, 208) = 39.19, p < .001; Step 2: R 2 = .35, F (3, 207) = 37.21, p < .001]. In the last step, the interaction terms were entered and the model accounted for 39 % of the severity of eating psychopathology variance [Step 3: F (4, 206) = 33.09; p < .001]. The regression coefficients analysis showed that the interaction between these two variables was significant [β = .21; t = 3.72; p < .001]. These results suggest the existence of a moderator effect of thought suppression on the association between social rank based on physical appearance and eating psychopathology symptoms.

-

2.

The moderator effect of thought suppression on the relationship between body image dissatisfaction and eating psychopathology

In the second model (Table 2), the same procedure was performed to explore the relationship between body image dissatisfaction (BD) and eating psychopathology moderated by thought suppression (WBSI). BMI and BD were entered in step one as predictors and WBSI was added in step two [Step 1: R 2 = .37, F (2, 208) = 61.00, p < .001; Step 2: R 2 = .45, F (3, 207) = 56.46, p < .001]. In the third step, the interaction variable was entered and the model accounted for 49 % of eating psychopathology’s variance [F (4, 206) = 49.99, p < .001]. The obtained regression coefficients results revealed that the interaction of the two variables was significant (β = .21; t = 4.15, p < .001). Hence, a moderator effect of thought suppression on the relation between body image dissatisfaction and eating psychopathology symptoms was found.

In both moderators’ analyses, when the interaction variables were entered on the regression models there was a significant increase in R 2. In addition, they also presented an expressive and significant effect on the severity of eating psychopathology. Therefore, interaction effects between thought suppression and social comparisons based on physical appearance and body image dissatisfaction were confirmed, suggesting that thought suppression moderates the effect of these risk factors on eating psychopathology severity.

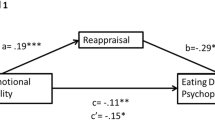

Two graphics were plotted to better understand the relation between these risk factors (SCPAS_Models and BD) and eating psychopathology severity with different levels of WBSI (Fig. 1 for SCPAS_Models; Fig. 2 for BD), considering one curve for each of the three WBSI levels (low, medium and high).

The graphic representation of model 1 (Fig. 1) revealed that, of the individuals who presented unfavorable social comparisons based on physical appearance, those who revealed higher tendencies to suppress thoughts (higher scores on WBSI) tended to present higher levels of eating psychopathology in comparison to those with medium and low scores on WBSI. Also, the same pattern was found for those individuals who presented more favorable social comparisons based on physical appearance. Nevertheless, in this case, the moderator effect of WBSI on the severity of eating psychopathology was weaker in comparison to the observed effect on medium to high values of SCPAS_Models.

As shown in Fig. 2, for the same level of body image dissatisfaction, participants who presented higher tendencies to thought suppression (higher WBSI scores) tended to show more eating psychopathology symptoms. From the graphic representation, it is possible to observe that the moderator effect of WBSI on the prediction of EDE-Q is stronger when dissatisfaction with body image is more intense.

Discussion

The present study highlights the role of general thought suppression on eating psychopathology, corroborating and adding to previous research [e.g., 24, 35]. Results showed that thought suppression was linked to the main risk factors for eating disorders (e.g., body image dissatisfaction and unfavorable social comparisons) and with eating psychopathology severity. These results support previous findings which revealed that thought suppression is associated with food cravings, binge-eating episodes and overall eating disorder symptoms [e.g., 25–34].

Furthermore, the moderator effect of thought suppression on the relationship between social comparisons through physical appearance and body dissatisfaction with eating psychopathology was explored, while controlling for BMI. In the first model, BMI revealed an independent and significant contribution to eating psychopathology severity. However, in model 2, BMI’s effect on EDE-Q was non-significant, suggesting that its impact on eating psychopathology symptoms is carried forward through body dissatisfaction.

Moreover, results indicated that the interaction between thought suppression and these risk factors presented a strong and significant effect on overall levels of eating psychopathology severity. Concerning social comparison through physical appearance, our results suggest that for the same level of social comparison, those young females who present higher levels of general thought suppression reveal higher eating disordered symptoms. Also, the graphic representation of this moderation analysis indicates that the damaging effect of thought suppression is more stressed when young females compare themselves more negatively. The same pattern was found for body image dissatisfaction. Indeed, for the same levels of body image dissatisfaction those young female who revealed higher tendencies to suppress thoughts display higher eating psychopathology severity in comparison to those who have lower levels of thought suppression. Interestingly, the impact of this interaction is more striking for young women who present higher levels of body image dissatisfaction. This suggests that thought suppression moderates (as it amplifies) the impact of these risk factors on disordered eating attitudes and behaviors.

Taken together, our findings suggest that higher levels of body image dissatisfaction and increased unfavorable social comparisons tend to be associated with an augmented use of thought suppression (i.e., engagement in more attempts to diminish or eliminate undesirable thoughts). However, this control strategy is ineffective and paradoxical as it may amplify the impact of body image dissatisfaction and unfavorable social comparison on eating psychopathology. Such results can be understood through the occurrence of a rebound effect of thought suppression, which increases the frequency, intensity and impact of the unwanted internal experiences [14–16]. Thus, it is possible that women become caught up in this vicious circle, in which body image dissatisfaction and unfavorable social comparisons are fueled by thought suppression, enhancing food, weight and body shape concerns and disordered eating behaviors.

Previous studies already demonstrated the importance of thought suppression in eating behaviors [e.g., 26, 27]. Nevertheless, as far as we know, this is the first study to explore the moderator effect of thought suppression on eating psychopathology. In fact, this is a key finding as it entails important research and clinical implications. Firstly, our data clarify the pervasive impact of thought suppression on the explanation of maladaptive eating attitudes and behaviors (e.g., dietary restriction and over concern with weight, shape and eating). Secondly, it points the importance of addressing thought suppression in young females with eating- and body-related difficulties. This is particularly relevant as it is not possible to prevent experiences of negative social comparison or body image dissatisfaction. Therefore, interventions should focus on the replacement of control strategies to deal with unwanted body-related internal experiences by the development of more adaptive ones (e.g., acceptance, defusion and mindfulness). Furthermore, the data found in this study are consistent with the results from recent intervention studies that used Mindfulness and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for body and eating difficulties [e.g., 48, 49].

Nevertheless, these results entail some methodological limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits causal conclusions that can be drawn from our findings. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine the directionality of the relations and to corroborate the moderation effect of thought suppression. Secondly, we chose to use a young female non-clinical sample as it resembles the age and sex risk features for eating disordered attitudes and behaviors [e.g., 50]. Nevertheless, future research should replicate these findings in clinical samples. Furthermore, the use of self-reported measures may compromise the generalization of the data. Furthermore, the use of the FRS to assess body dissatisfaction has been the focus of some criticism. Still FRS’s simplicity makes it especially useful instrument and in Caucasian populations it allows robust results. Also we recognize that these models present some limitations since eating psychopathology has a multidetermined and complex nature and that other risk factors (e.g., dieting, history of eating disordered behavior) and emotional regulation processes (e.g., rumination, cognitive fusion) may be involved. However, these models were intentionally restrained to specifically explore the role of general thought suppression.

In conclusion, the current study adds to previous knowledge as it discloses the pervasive and amplifying effect of thought suppression on the relation between eating psychopathology’s main risk factors and maladaptive eating attitudes and behaviors.

References

Stice E (2001) A prospective test of the dual path-way model of bulimic pathology: mediating effects of dieting and negative affect. J Abnorm Psychol 110:124–135. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.110.1.124

Stice E, Marti CN, Durant S (2011) Risk factors for onset of eating disorders: evidence of multiple risk pathways from an 8-year prospective study. Behav Res Ther 10:622–627. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.009

Pinto-Gouveia J, Ferreira C, Duarte C (2014) Thinness in the pursuit for social safeness: an integrative model of social rank mentality to explain eating psychopathology. Clin Psychol Psychother 21(2):154–165. doi:10.1002/cpp.1820

Burkle MA, Ryckman RM, Gold JA, Thornton B, Audesse RJ (1999) Forms of competitive attitude and achievement orientation in relation to disordered eating. Sex Roles 40:853–870. doi:10.1023/A:1018873005147

Ferreira C, Pinto-Gouveia J, Duarte C (2013) Physical appearance as a measure of social ranking: the role of a new scale to understand the relationship between weight and dieting. Clin Psychol Psychother 20:55–66. doi:10.1002/cpp.769

Kanazawa S, Kovar JL (2004) Why beautiful people are more intelligent. Intelligence 32:227–243. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2004.03.003

Sypeck MF, Gray JJ, Etu SF, Ahrens AH, Mosimann JE, Wiseman CV (2006) Cultural representations of thinness in women, redux: Playboy magazine’s depictions of beauty from 1979 to 1999. Body Image: Int J Res 3:229–235. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.07.001

Webster M, Driskell JE (1983) Beauty as status. Am J Sociol 89:140–165

Ferreira C, Pinto-Gouveia J, Duarte C (2013) Drive for thinness as a women’s strategy to avoid inferiority. Int J Psychol Psychol Ther 13(1):15–29

Gilbert P (2002) Body shame: a biopsychosocial conceptualisation and overview, with treatment implications. In: Gilbert P, Miles J (eds) Body shame: conceptualisation, research and treatment. Brunner, London, pp 3–54

Troop NA, Allan S, Treasure JL, Katzman M (2003) Social comparison and submissive behavior in eating disorders. Psychol Psychother: Theory Res Pract 76:237–249. doi:10.1348/147608303322362479

Barkow J (1980) Prestige and self-esteem: a biosocial interpretation. In: Omark DR, Strayer FF, Freedman DG (eds) Dominance relations: an ethological view of human conflict and social interaction. Garland STPM Press, New York, pp 319–332

Puhl RM, Heuer CA (2009) The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity 17(5):941–964. doi:10.1038/oby.2008.636

Salkovskis PM, Campbell P (1994) Thought suppression induces intrusion in naturally occurring negative intrusive thoughts. Behav Res Ther 32:1–8. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(94)90077-9

Wegner DM, Schneider DJ, Carter S, White T (1987) Paradoxical effects of thought suppression. J Personal Soc Psychol 53:5–13. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.53.1.5

Abramowitz J, Tolin D, Street G (2001) Paradoxical effects of thought suppression: a meta-analysis of controlled studies. Clin Psychol Rev 21:683–703. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00057-X

Wegner DM, Zanakos S (1994) Chronic thought suppression. J Pers 62:615–640. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00311.x

Wenzlaff RM, Bates DE (1998) Unmasking a cognitive vulnerability to depression: how lapses in mental control reveal depressive thinking. J Personal Soc Psychol 75:1559–1571. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.6.1559

Shipherd JC, Beck JG (1999) The effects of suppressing trauma-related thoughts in women with rape-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther 37:99–112. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00136-3

Janeck AS, Calamari JE (1999) Thought suppression in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Cogn Ther Res 23:497–509. doi:10.1023/A:1018720404750

Lavender JM, Anderson DA (2010) Contribution of emotion regulation difficulties to disordered eating and body dissatisfaction in college men. Int J Eat Disord 43:352–357. doi:10.1002/eat.20705

Polivy J (1998) The effects of behavioral inhibition: integrating internal cues, cognition, behavior, and affect. Psychol Inq 9:181–204. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0903_1

Ward T, Bulik CM, Johnston L (1996) Return of the suppressed: mental control in bulimia nervosa. Behav Chang 13:79–90

Wenzlaff RM, Wegner DM (2000) Thought suppression. In: Fiske ST (ed) Annual review of psychology, vol 51. Annual Reviews, Palo Alto, CA, pp 59–91

Barnes RD, Tantleff-Dunn S (2010) Food for thought: examining the relationship between food thought suppression and weight-related outcomes. Eat Behav 11:175–179. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.03.001

Barnes RD, Masheb RM, Grilo CM (2011) Food thought suppression: a matched comparison of obese individuals with and without binge eating disorder. Eat Behav 12:272–276. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.07.011

Barnes RD, Tantleff-Dunn S (2010) A preliminary investigation of sex differences and the mediational role of food thought suppression in the relationship between stress and weight cycling. Eat Weight Disord: Stud Anorex Bulim Obes 15:e265–e269

Barnes RD, Masheb RM, White MA, Grilo SM (2013) Examining the relationship between food thought suppression and binge eating disorder. Compr Psychiatry 54(7):1077–1081. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.04.017

Soetens B, Braet C (2006) ‘The weight of a thought’: food-related thought suppression in obese and normal-weight youngsters. Appetite 46:309–317. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2006.01.018

Soetens B, Braet C, Dejonckheere P, Roets A (2006) ‘When suppression backfires’: the ironic effects of suppressing eating-related thoughts. J Health Psychol 11:655–668

Pop M, Miclea S, Hancu N (2004) The role of thought suppression on eating-related cognitions and eating pattern. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 28:S222

Ogden J (2003) What do symptoms mean? Br Med J 327(7412):409–410. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7412.409

O’Connell C, Larkin K, Mizes JS, Fremouw W (2005) The impact of caloric preloading on attempts at food and eating-related thought suppression in restrained and unrestrained eaters. Int J Eat Disord 38(1):42–48. doi:10.1002/eat.20150

Herman CP, Polivy J (1993) Mental control of eating: excitatory and inhibitory food thoughts. In: Wegner DM, Pennebaker JW (eds) Handbook of mental control. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, pp 491–505

Lavender JM, Jardin BF, Anderson DA (2009) Bulimic symptoms in college men and women: contributions of mindfulness and thought suppression. Eat Behav 10:228–231. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.07.002

Lewis DM, Cachelin FM (2001) Body image, body dissatisfaction, and eating attitudes in midlife and elderly women. Eat Disord 9(1):29–39. doi:10.1080/106402601300187713

Tiggemann M, Lynch J (2001) Body image across the life span in adult women: the role of self-objectification. Dev Psychol 37:243–253. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.37.2.243

Wegner DM, Pennebaker JW (1993) Changing our minds: an introduction to mental control. In: Wegner DM, Pennebaker JW (eds) Handbook of mental control. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, pp 1–12

Pinto-Gouveia J, Albuquerque P (2007) Versão portuguesa do inventário de supressão do urso branco. Unpublished manuscript

Thompson JK, Altabe MN (1991) Psychometric qualities of the figure rating scale. Int J Eat Disord 10:615–619. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199109)10:5

Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ (1994) Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord 16:363–370. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199412)16:4

Machado PP, Martins, C, Vaz, A, Conceição E, Pinto-Basto, Gonçalves S Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q): psychometric properties and norms for the portuguese population. Eur Eat Disord Rev. doi:10.1002/erv.2318

Fairburn CG (2008) Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guilford Press, New York

Cohen J, Cohen P, West S, Aiken L (2003) Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioural sciences, 3rd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New Jersey

Aiken L, West S (1991) Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Jose PE (2013) ModGraph-I: a programme to compute cell means for the graphical display of moderational analyses: the internet version, Version 3.0. Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand. Retrieved [November, 2013] from http://pavlov.psyc.vuw.ac.nz/paul-jose/modgraph/

Kline RB (2005) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 2nd edn. The Guilford Press, New York

Kristeller JL, Hallett CB (1999) An exploratory study of a meditation-based intervention for binge eating disorder. Health Psychol 4(3):357–363. doi:10.1177/135910539900400305

Pearson A, Follette VM, Hayes SC (2011) A pilot study of acceptance and commitment therapy as a workshop intervention for body image dissatisfaction and disordered eating attitudes. Cogn Behav Pract 19:181–197. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.03.001

Luce KH, Crowther JH, Pole M (2008) Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q): norms for undergraduate women. Int J Eat Disord 41(3):273–276. doi:10.1002/eat.20504

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declared no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards

The study respected the ethical standards and was approved by the Ethics Committee Boards of all the educational institutions enrolled in the study.

Informed Consent

All participants (and their parents, if they were underage) were required to sign a consent form to take part in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferreira, C., Palmeira, L., Trindade, I.A. et al. When thought suppression backfires: its moderator effect on eating psychopathology. Eat Weight Disord 20, 355–362 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0180-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0180-5