Abstract

Purpose of the review

Humanitarian crises inherently exacerbate strains on social support and risks of gender-based violence (GBV), especially for women and girls. However, little is known in regard to the linkage between social support and GBV in humanitarian settings. This systematic review sheds light on this scientific gap by synthesizing evidence examining the role, measurement, and impact of social support and GBV among women and girls in humanitarian settings.

Recent findings

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, a total of 21 articles were included from 1247 reviewed abstracts. Despite varied measurement and study designs, findings indicated an emerging literature base demonstrating that social support, in the right form and under the right conditions, can enable positive outcomes in terms of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of GBV. In particular, our findings highlight the value of informal social support at the neighborhood and community level, as well as within targeted groups such as peer networks of GBV survivors.

Summary

We conclude that research, programming, and policies should carefully consider how GBV and social support are experienced within and across humanitarian settings in order to support women and girls, who are most vulnerable to the compounding strains of humanitarian conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Humanitarian conflict, displacement, and natural disasters disrupt social support by severing relational ties between individuals, families, and communities [1]. Crises also erode the social fabric of communities, strain connections, undermine trust, and deplete the social capital of those impacted [2]. Women, and survivors of gender-based violence (GBV) in particular, are vulnerable to social disruption when exposed to crises. GBV is associated with social alienation and estrangement [21, 24], which can lead to loss spirals of social resources, low perceptions social support among survivors, and impede recovery. Moreover, women are more likely to carry heavier family burdens during and after conflict, more than twice as likely to develop mental health disorders as a result of trauma, and face higher downsizing of social networks and sources of support [1, 3]. Whether by reestablishing relationships or fostering intra-community connections, social support can foster help-seeking behaviors and recovery among GBV survivors [4]. Importantly, fostering social support can mitigate the worst effects of war and displacement [5]; thus, it is critical that the most vulnerable to social disruption are prioritized with socially appropriate and transformative research and humanitarian intervention.

Although no global definition of social support exists, it can be characterized by perceived or received exchanges between individuals or groups[6, 7]. Perceived social support measures how much support is potentially available from existing social ties, while received social support assesses past utilization of support from social ties. Social support can also be categorized as functional (ex. the availability or role of ties) or structural (ex. the number of strong or weak ties). The types of social support provided may be emotional, instrumental, informational, companionship, or validation [8], and social support can be enacted through informal (i.e., peers, family, friends) or formal (i.e., structural providers) relationships [9]. Social support, in particular forms, has been connected to positive health outcomes [8, 10, 11]. In addition to its ability to positively influence health, social support has been shown to protect individuals from the adverse effects of stress and promote healthy coping mechanisms [8]. Social bonds play an especially vital role in posttraumatic stress (most crucially by fostering a sense of safety with others and buffering against psychological distress [12, 13]). However, the mechanisms, forms, and consequences of social support are highly contextualized and dependent on personal, environmental, and cultural factors [7, 9]; little attention has been paid to the potential role or definition of social support in humanitarian settings and even less among survivors of GBV in humanitarian settings.

One in four women and girls will experience violence in her lifetime [14], a threat that is elevated in humanitarian settings [15, 16]. GBV faced by women and girls in emergency contexts represents a continuum of violence, with women and girls at risk of violence exposure before, during, and after a conflict or climate disaster in various forms and severity. GBV can be deployed as a conflict tactic to displace communities, seize land and resources, recruit soldiers, and generate repression, terror, and control [15, 17, 18]. Most GBV during crises, however, occurs at home or within communities and families, magnifying violence and inequities already present before the crisis [16]. These incidents of violence result in exacerbated negative social, economic, health, and psychosocial effects [15, 19]. Studies have shown that survivors of GBV encounter increased likelihood of reproductive issues, sexually transmitted infections, unwanted pregnancies, depression, anxiety, and developing unhealthy coping strategies like drug use [18,19,20,21,22,23].

Previous studies have demonstrated the linkage between social support and GBV for women and girls [25], but there remains a knowledge gap in examining this linkage in emergencies. In non-humanitarian settings, social support (formal and informal) is associated with reducing poor mental and physical health, anxiety, depression, PTSD, and suicide attempts for survivors [26,27,28]. Moreover, social support can exert strong and consistently positive effects on survivors’ quality of life, even if developed at a later point in time after exposure to violence [27, 29]. This echoes intervention research conducted in low-resource settings, where family, friends, and community members may provide emotional support to survivors and serve as connectors to formal services [30]. The positive benefits of social support for survivors, however, are dependent on the quality, type, and perception of social support provided. For example, negative reactions to disclosures of GBV can result in poorer recovery and adverse mental health for survivors [28, 31]. This frequently stems from stigmas related to GBV and has the potential to induce negative coping strategies and self-blame among survivors [31, 32].

To date, research has overlooked the complexities of social support for GBV survivors in humanitarian settings. Survivors may experience unique forms of social support in humanitarian settings. Given the weakening of community networks and social structures in emergency contexts, examining the scope of social support during crises is critical to inform prevention and response. This systematic review sheds light on this empirical gap and examines the role, measurement, and impact of social support and GBV in humanitarian settings among women and girls. Understanding the linked role of social support and GBV in crises can inform policy, programming, and practice for women and girls, particularly GBV survivors and those at risk of GBV, as well as their families and communities.

Methods

Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines[33], we conducted a systematic review of peer-reviewed articles published between 2005 and 2021 that evaluated social support among women and girls who have experienced GBV in humanitarian settings. This date was chosen to align with standardized violence definitions brokered by the WHO Multi-Country Study in 2005 on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women[34]. The definition of GBV was guided by the terminology set by the 2015 Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Guidelines for Gender-Based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Settings, which states that GBV is “an umbrella term for any harmful act that is perpetrated against a person’s will and that is based on socially ascribed (i.e., gender) differences between males and female” [35]. All studies were conducted in a country that received humanitarian funding through the Consolidated Appeals Process or Humanitarian Response Planning between 2005–2020 [36].

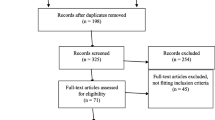

The search strategy comprised of peer reviewed studies that were available in English (See Supplemental Material). The search terms included women and girls (e.g., “female” and “wife”) who have faced humanitarian conflict, war, terrorism, or natural disaster (e.g., “refugee”, “famine”, “displacement”, and “earthquake”). GBV was searched using terms such as “violence against women”, “early marriage”, “abuse”, and “genital cutting”. Finally, social support was searched using terms such as “psychosocial support”, “social capital”, and “social cohesion”. We applied the search terms to the databases Medline via Ebscohost (n = 200), Scopus via Scopus (n = 806), and PsycInfo via Ebscohost (n = 241). Articles were imported into a systematic review software, Covidence, to remove duplicates and enable abstract review. The full text review and data extraction were completed in Excel. All conflicts between authors during the abstract and full-text review stages were reviewed by a third author to determine final decision.

Articles were reviewed based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method studies were included if they included and examined the linkage between at least one form of GBV and at least one form of social support among women and/or girls affected by a humanitarian emergency. Articles were excluded if not available in English. Literature reviews, dissertations, and systematic reviews were also excluded. Next, articles were excluded if there was no measurement of social support and/or GBV. Articles were excluded if only men or boys were sampled or if findings were not disaggregated for women and girls, if the sample was not conflict/disaster affected, or if the study sample focused on military members or veterans. Between the abstract and full text review, articles were limited again explicitly to only include articles from countries that were listed in the Consolidated Appeals Process or Humanitarian Appeals Process for at least one year between 2005 and 2020.

The final number of selected articles for inclusion and from which data were extracted was 21. Data extraction was informed by an explicit interest in the (1) measurement of social support and GBV among humanitarian-affected women and girls, and (2) findings associated with the confluence of social support and GBV among humanitarian-affected women and girls. Other data extracted included study design, study aims, theoretical framework, population, geographic location, time of data collection, and analytical approach. The article review process is represented in Fig. 1.

Results

Overview of Study Characteristics

A total of 21 articles from 20 studies were included (see Table 1). While the review criteria enabled articles published since 2005 to be eligible, the vast majority of the 21 articles (71.24%; n = 15) were published between the years of 2018 and 2021, signaling more recent focus and interest in this subject area. Only six eligible articles were published before 2018, with the earliest publication from 2010. The greatest number of studies (60.00%, n = 12) were from humanitarian settings in sub-Saharan Africa (Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo [DRC], Ghana, Kenya, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, and Uganda). The remainder of studies collected data from humanitarian settings in Southeast Asia (Thai-Myanmar border), the Middle East (Jordan, Lebanon, and Palestine), South America (Ecuador), and the Caribbean (Haiti). The country with the highest number of studies was the DRC (n = 4). Aside from the two articles examining the context of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, study contexts were conflict-affected rather than natural disaster-affected.

While all studies included participants who were GBV survivors, just under half of the studies (45.00%; n = 9) were limited to this population exclusively. Most studies included women aged ~ 25 to 49 (85.00%; n = 17) and/or young women aged ~ 18 to ~ 24 (80.00%; n = 16); fewer studies included women aged ~ 50 or older (25.00%; n = 5) and/or girls under the age of 17 or18 (30.00%; n = 6). Only four studies focused specifically on young women and/or girls. While the research questions or aims of most articles included GBV-specific considerations (87.71%; n = 18), only seven articles included some mention of social support within their primary research questions or aims. Only three of those seven articles used the term “social support” within their research questions or aim. Thus, GBV appears as a central interest in the included articles but social support was more often a secondary interest.

Overview of Study Design

Aside from temporality, study designs varied across the 23 articles stemming from the respective data collection tools and primary analytic procedure (presented in Table 2) and extending to measurement of social support and GBV (presented in Tables 3 and 4) and covariate or other construct measurement (not presented). The temporality of study designs was largely cross-sectional (75.00%; n = 15); however, five of the studies integrated longitudinal data. All of the longitudinal studies were quantitative. These longitudinal studies enabled causal interpretation using both linear/logistic regressions or linear growth modeling, compared to the associative findings inherent with the cross-sectional studies. The eight identified qualitative studies were all cross-sectional. Qualitative studies largely employed focus group discussions (n = 5) or key informant interviews (n = 4), with only one study including other data collection tools of observation and document review. Two mixed-method studies were identified: one that relied on cross-sectional data and integrated findings from its propensity score matching alongside findings from narrative and thematic analysis [37], and the other used mapped qualitative themes with quantitative variables and utilized logistic regressions [38].

Quantitative Measurement of Gender-Based Violence and Social Support

Tables 3 and 4 outline the GBV and social support quantitative and qualitative measurement approaches, respectively. Two of the 15 quantitative or mixed method articles did not measure GBV because their samples were already restricted to women who had experienced IPV or sexual violence. Eight of the remaining 13 articles measured multiple forms of GBV. Seven quantitative measures included any form of GBV, including sexual, physical, or emotional IPV. The measurement of non-intimate partner violence focused most often on sexual violence (n = 7), with only three articles examining physical violence perpetrated by non-intimate partners. The recall period for violence also varied: lifetime (n = 4), past year (n = 3), past six months (n = 2), during certain ages (n = 1), and during or since a specific event (n = 4). Nearly all of the quantitative articles relied on a binary GBV measurement (n = 12), with only one article using an ordinal measurement of sexual assault. Most measures of GBV were derived from standardized measures (n = 10), with the WHO Violence against Women Instrument being the most commonly used (n = 4).

Standardized measures of social support in quantitative or mixed method articles were less common (n = 7) and guiding social support frameworks or definitions were inconsistent between articles. Two articles utilized the help-seeking behavior questions from the WHO Violence against Women Instrument; this series of three questions asks whether survivors ever sought help to stop the violence — if yes, from whom help was sought and, if no, whether survivors ever told anyone about the violence. An additional two articles utilized the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) — a 12-item measure of perceived adequacy of social support from three sources of informal support (family, friends, and/or significant other) [39]. No study included measures that classify social support into different behavioral transactions and types of social functioning within a community, such as the Inventory of Socially Supportive Behaviors (ISSB) and Social Adjustment Scale-II (SAS-II) [40, 41].

Many articles either did not specify the source of social support measurement or indicated the measurement was designed by the study team (n = 8). One quantitative article was a notable exception in its measurement of various domains of social support including emotional support and practical support, in addition to examining the provision and seeking of informal support [1]. Wachter and colleagues (2018) integrated qualitative research to inform specific questions related to assessing the extent of contact with others, the provision of support, and context-specific help-seeking behavior; qualitative research also informed their adaptation of the Integrated Questionnaire for the Measurement of Social Capital [42] to measure practical support and long/short-term anticipated support.

For those authors who did not use specific social support terminology or cite standardized measures when describing their social support measurement, various functions of social support were measured, such as help-seeking behavior or availability of support. While the exact social support questions were rarely described, the description of help-seeking behavior questions often aligned with the WHO Violence against Women Instrument. Availability of support, on the other hand, tended to focus on the perceived number of friends and/or family available generally or for a certain situation; again, these questions may have aligned with item(s) from standardized measures, like the MSPSS, but it was difficult to determine without source reference or question extracts.

The recall period for social support was also less explicit than GBV experience. However, most studies examined the current state or perceptions of social support at the time of data collection (n = 9). Other recall periods included lifetime (n = 3), past year (n = 2), past 4-weeks (n = 1), during or since a specific event (n = 1).

Qualitative Measurement of Gender-Based Violence and Social Support

The qualitative and mixed method articles were less likely to measure GBV forms and more likely to limit the sample to GBV-affected women and girls. Only two of the nine qualitative or mixed method studies utilized qualitative methods to identify GBV experience. Neither of these two studies examined the exact form of GBV experienced; rather, the studies used either a listing experiment [43] or a question on GBV service utilization [44] to determine if a research participant had experienced IPV or GBV in her lifetime.

While guiding social support frameworks or definitions remained lacking, social support measurement was more robust in the qualitative and mixed method studies than the quantitative studies. Participants in all nine of these studies were asked or probed to describe their current social support, as well as their social support experiences during their lifetime (n = 1) or time as a child soldier (n = 1). The themes that arose from these questions and probes focused on informal social support among friends and family and at the community-level (incl. support groups, neighbors, and local leaders). Respondents were able to describe the context-specific considerations of their social support, particularly when describing how the community and social norms impact the availability and function of their social networks. Respondents often described the ways in which informal or formal social support could be accessed and under what conditions. The qualitative measurement approach enabled exploration into the diverse ways social supports are understood, developed, retained, and accessed in different contexts.

Overview of Findings Linking Social Support and GBV Among Humanitarian-Affected Women and Girls

This review also examined findings linking social support and GBV in humanitarian settings, with an explicit interest in understanding the extent to which social support may encourage primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of GBV. While three articles addressed other linkages between social support and GBV (e.g., how peer support among IPV survivors may enable disclosure of stigmatized health outcomes), nearly all of the articles addressed primary, secondary, and/or tertiary prevention of GBV (85.71%; n = 18).

Four articles explored how social support may prevent GBV from occurring in the first place (i.e., primary prevention). These findings were mixed and the statistically significant quantitative findings tended to focus on the effect of community and family social support in the prevention of IPV. For example, having family in the area and neighborhood connectiveness were both associated with preventing emotional IPV in Ecuador among Colombian women, whose social networks were fractured as a result of forced displacement [38, 45]. However, similar linkages were not found for physical nor sexual IPV. In contrast, respondents in the DRC did not feel that family or community resources prevented IPV [48], perhaps due to the normalization of violence.

Addressing GBV prevention at the secondary level (i.e., detecting violence early and/or preventing worsening/reoccurrence) was also not common (n = 5). Findings related to secondary prevention were mostly from qualitative evidence. The qualitative evidence highlighted the role of community-support and contextual-situations and the risk of violence (often negatively). For example, community social networks promoting early marriage with the hopes of protecting girls [46] or urban environments inherently fracturing pre-migration social cohesion [47]. Conversely, direct and informal social support provision from family and local leaders was described as being able to protect women and girls from violence insofar as the providers of the social support understood the risks that women and girls face in relation to violence, especially IPV [48]. One article also described how access to formal support through GBV services empowered women and girls and taught them strategies to improve their safety and health [44].

Most common in both qualitative and quantitative studies was addressing GBV at the tertiary level (n = 13), preventing mortality and morbidity associated with violence. Examples of tertiary prevention, such as service provision for survivors, focused primarily on mental health and general functioning or coping. While most of the quantitative findings indicated that social support could mitigate the mental health burden of GBV experiences, findings were not universal as at least one study demonstrated how certain sources of social support were statistically influential while others were not [38]. Qualitative findings bolstered this finding by describing in depth how certain expressions of social support (e.g., from persons with similar experiences who describe their healing journal) may be particularly beneficial compared to others (e.g., certain expressions of family support toward girls who experienced sexual violence). Several studies also discussed how social support is linked to accessing services among GBV survivors.

Figure 2 also presents studies that examined how GBV may influence social support or how social support and GBV may work together to address related outcomes. For example, findings examining social support (n = 3) demonstrated how certain forms of GBV may influence accessing of social support networks (e.g., survivors who experienced conflict-related sexual violence having higher odds of reporting than other GBV survivors) as well as how GBV experiences can influence available social supports (e.g. increasing the number and depth of friendships with other survivors while losing connections with former friends as an implication of GBV experience). The “non-GBV or social support” findings from two articles focused (1) on how insufficient social support and GBV, when integrated in the same model, were both negatively associated with perinatal depression on the Thai-Myanmar border [49], and (2) how support from peers enabled disclosure of sensitive health information to family members in Rwanda [50].

Discussion

Bearing in mind the respective and potentially compounding strain of humanitarian crises on social support [2] and GBV [31], this review synthesized peer-reviewed literature published between 2005 and 2021 to examine linkages between social support and GBV among women and girls in humanitarian settings. Our findings indicate that the mechanisms underlying social support paradigms in humanitarian contexts have not been extensively examined and lack conceptual framing, and few studies have explicitly focused on examining how social support can mitigate adverse outcomes related to GBV risk and experience in humanitarian settings. However, we identified an encouraging upsurge in relevant literature since 2018, suggesting the timeliness of this review to consolidate a way forward for future research and intervention. This emerging literature base includes important study considerations — particularly with respect to the GBV-affected population of focus (various forms of GBV experienced but primarily IPV), geography (mostly localized to Sub-Saharan Africa), and scope (examination of social support was often not included as a primary aim). A central finding of our synthesis was that social support, in the right form and under the right conditions, can enable positive outcomes at the primary, secondary, and/or tertiary levels prevention of GBV. Moreover, our findings add to an existing evidence base that demonstrates the value of informal [25, 30] and formal [51] social support, while also highlighting gaps in shared definition and measurement of social support.

Implications for Measurement

Recognizing that social support may present uniquely in humanitarian settings, especially among women and girls, more robust measurement approaches are needed. Our findings shed light on the disjointed conceptual understanding and measurement of social support among included studies, as well as a lack of exploration into the mechanisms that influence the linkage between social support and GBV. The broader social support literature supports two foundational pathways in which social support may operate in humanitarian settings: the Main Effect theory which hypothesizes that social support is continuously influential and the Buffer Effect theory which concentrates on the interplay between social support and stressors [8]. The Buffer Effect (or Stress-Buffering Hypothesis) proposes that social support can influence outcomes by protecting individuals from the most adverse effects of stressors. While there is a notable absence of research examining the Buffer Effect among GBV survivors in humanitarian settings, researchers have hypothesized that “social support of the right type, provided at the right time and level, can mitigate the worst effects of war and displacement [5].” Work from Cutrona and Russel [52] highlights that specific supportive actions are only useful insofar as they compensate for the stressor. In this way, social support that directly counteracts the embedded structural inequalities and harmful social norms that encourage violence may be especially impactful among GBV survivors in humanitarian settings.

Building on this call for more mechanistic research, it is also important that the conceptualization of social support allows for enough nuance to capture which forms of social support impact which forms of GBV. For example, research has highlighted that there is implicit power in subjective perception (perceived support) rather than actual utilization of social support (received support) [53]; however, GBV survivors may have distinct needs for support, especially regarding health or social service utilization, that could elevate the importance of received support. Along the same lines, instrumental support (offering or providing distinct tangible help) or informational support (sharing advice or fact-based information) may be uniquely influential, despite the tendency for global social support research to focus on emotional support (the provision of comfort or empathy). When formal support through service provision is impractical or unavailable, survivors may benefit more from informal support provided by friends, family, or community members. Thus, the complexity and diversity available in social support definitions must be carefully considered.

Similarly, it is important to understand how social support presents among and between populations and consider the type of humanitarian crisis exposure. Particularly vulnerable or marginalized populations, such as those who identify as LGBTQ, may not only experience specific forms of GBV but may also prefer more specific-peer groups composed of others in their community. One of the included studies by Walstrom and colleagues [50] identified the importance of peer-groups among HIV-affected Rwandan women who are trauma survivors, as their shared identity enabled open conversations and processing of their lived experiences as members of a marginalized population. There will also be differential social support impacts and GBV risks based on the type of humanitarian crisis. A simple consideration to be made is the displacement characteristics of a crisis and among individuals. While displacement is likely to disrupt community structure, kindship groups may remain (e.g., as part of protracted natural disaster displacement like droughts) or may be completely dissolved (e.g., rapid displacement resulting from sudden onset warfare). These nuanced considerations are critical to more robust understanding of the important linkage between social support and GBV, as well as tailoring interventions to address this linkage.

Moreover, there is unclear evidence regarding the validity or appropriateness of common social support scales in humanitarian settings. Research may benefit from participatory and/or qualitative approaches to measuring social support. In particular, filling this measurement gap could inform understanding of the unique ways that social support can be strengthened organically among women and girls in humanitarian settings (esp. in recognition of how women may informally and collectively establish networks to address local issues).

Implications for Programming and Policy

Our findings add to the global evidence base examining GBV and social support [31, 54,55,56,57] by providing insights into this linkage in humanitarian settings which may ultimately inform future programming and policy. Regarding formal social support, evidence from this review indicated that GBV services could support secondary GBV prevention by teaching strategies to improve the safety and health of survivors [44]. While evidence of formal social support was limited, the provision of this support by NGOs is critical to consider given the fundamental societal breakdown during humanitarian crises, including the erosion of formal social support [58, 59]. Local and international NGOs, as well as community organizers, often bear the responsibility of supporting survivors in humanitarian settings in place of pre-humanitarian service provision which tends to be coordinated by the government or other authorities.

Unlike programming in stable settings, humanitarian response often focuses on short-term programming and outcomes which may overlook the role that building social support can have in sustaining or inhibiting long-term success, especially for mental health outcomes [60]. Our findings related to informal social support may be well positioned to fill this gap as they highlight as the value of solidarity [61] or peer-groups [50], which may organically sustain or grow beyond the duration of an intervention or funding cycle. Moreover, our identification of the impact of informal social support at the community level aligns with broader social support and GBV research that highlights the unique value of community levels of intervention [62], such as training community activists. However, conceptualization of how an informal social support intervention may address primary, secondary, and tertiary GBV prevention is important to consider as these social support interventions are not a catch-all approach to addressing GBV. For example, research has demonstrated the limits of community-level social support interventions insofar as community responses to IPV in refugee contexts do not implicitly protect women from future violence [63]. Thus, culturally tailored social support interventions have the ability to reduce the effects of trauma in humanitarian settings [5], but researchers must carefully consider the hypothesized pathways and extent that targeted forms of social support may meaningfully address primary, secondary, and/or tertiary GBV prevention.

Study Limitations

The varied study design and measurement approaches impeded comparability between studies; thus, the findings describe the general state of the literature without providing a detailed understanding of underlying mechanisms through which social support may address GBV or vice versa. The varied definition and understanding of social support terminology limited the interpretation of articles, while also highlighting an area for consideration in future research. While the selection of the three databases for this review was based on consultation with systematic review experts and discussion with stakeholders, a broader search would have yielded more abstracts for review, potentially resulting in more full text articles for data extraction. Similarly, broadening our study to include articles written in languages other than English could have provided more articles for inclusion. This is an important limitation, especially given the focus on humanitarian settings were English is not the dominant language; however, the shared language capacities of the study team limited our ability to include non-English articles. Finally, grey literature was excluded from this review but should be further explored, particularly in regard to examining applied humanitarian programming and policy.

Conclusion

Although findings from this review document that social support has a meaningful role in the lives of GBV survivors, further research must be conducted to robustly examine the linkage between social support, in its diverse and complex conceptions, and GBV in humanitarian settings. Our findings highlight the emerging foundation of knowledge to guide this future research and emphasize that social support can be valuable to GBV survivors and those at risk of GBV. Contextual considerations are critical as experiences of both GBV and social support vary across contexts and lived experiences of women and girls. Supporting those most vulnerable to the compounding strains of humanitarian conflict requires that programming and policies purposefully consider the role of social support in addressing primary, secondary, and/or tertiary prevention of GBV in humanitarian settings.

References

Wachter K, Gulbas LE. Social support under siege: an analysis of forced migration among women from the Democratic Republic of Congo. Soc Sci Med. 2018;208:107–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.056.

Strang A, O’Brien O, Sandilands M, Horn R. “Help-seeking, trust and intimate partner violence: social connections amongst displaced and non-displaced Yezidi women and men in the Kurdistan region of northern Iraq,” Confl. Health, 2020;14(61) https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-020-00305-w.

Araya M, Chotai J, Komproe IH, de Jong JTVM. Gender differences in traumatic life events, coping strategies, perceived social support and sociodemographics among postconflict displaced persons in Ethiopia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:307–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-007-0166-3.

Stark L, Robinson MV, Seff I, Gillespie A, Colarelli J, Landis D. The effectiveness of women and girls safe spaces: a systematic review of evidence to address violence against women and girls in humanitarian contexts. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838021991306.

Almedom AM. “Factors that mitigate war-induced anxiety and mental distress,” J. Biosoc. Sci., 2004;36(4) https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932004006637.

Barrera M. “Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models,” Am. J. Community Psychol., 1986;14(4) https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00922627.

Gottlieb BH, Bergen AE. “Social support concepts and measures,” J. Psychosom. Res., 2010;69(5) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.001.

Cohen S, Lakey B. “Social support theory and measurement,” in Social Support Measurements and Intervention: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists, S. Cohen, L. G. Underwood, and B. H. Gottlieb, Eds. Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 29–52. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1093/med:psych/9780195126709.003.0002.

Williams P, Barclay L, Schmied V. “Defining social support in context: a necessary step in improving research, intervention, and practice,” Qual. Health Res., 2004;14(7) https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732304266997.

Cobb S. “Social support as a moderator of life stress,” Psychosom. Med., 1976;38(5) [Online]. Available: https://journals.lww.com/psychosomaticmedicine/Fulltext/1976/09000/Social_Support_as_a_Moderator_of_Life_Stress.3.aspx.

Kawachi I, Berkman LF. “Social ties and mental health.,” J. Urban Health Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med., 2001;78(3) https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/78.3.458.

Charuvastra A, Cloitre M. Social bonds and posttraumatic stress disorder. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:301–28. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085650.

Cohen S, Wills TA. “Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis,” Psychol. Bull., 1985;98(2) https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310.

WHO, “Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018,” World Health Organization: Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022256. Accessed 29 Nov 2021.

Stark L, Seff I, Reis C. “Gender-based violence against adolescent girls in humanitarian settings: a review of the evidence,” The Lancet, 2020;5(3) https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30245-5.

Stark L, Ager A. “A systematic review of prevalence studies of gender-based violence in complex emergencies,” Trauma Violence Abuse, 2011;12(3) https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838011404252.

Marsh M, Purdin S, Navani S. “Addressing sexual violence in humanitarian emergencies,” Glob. Public Health, 2006;1(2) https://doi.org/10.1080/17441690600652787.

Stark L, Thuy Seelinger K, Ibala R, Mukwege D. Prevention of conflict-related sexual violence in Ukraine and Globally. The Lancet. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00840-6.

Meinhart M, et al. Identifying the Impact of intimate partner violence in humanitarian settings: using an ecological framework to review 15 years of evidence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:6963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136963.

Campbell J. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359(9314):1331–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8.

Coker AL, et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(4):260–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00514-7.

Grose RG, Roof KA, Semenza DC, Leroux X, Yount KM. Mental health, empowerment, and violence against young women in lower-income countries: A review of reviews. Aggress Violent Behav. 2019;46:25–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.01.007.

Grose RG, Chen JS, Roof KA, Rachel S, Yount KM. “Sexual and reproductive health outcomes of violence against women and girls in lower-income countries: a review of reviews,” J. Sex Res., 2020; pp. 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1707466.

Shumm JA, Briggs-Phillips M, Hobfoll SE. “Cumulative interpersonal traumas and social support as risk and resiliency factors in predicting PTSD and depression among inner-city women,” J. Trauma. Stress, 2006;19(6) https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20159.

Sylaska KM, Edwards KM. Disclosure of intimate partner violence to informal social support network members: a review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2014;15(1):3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838013496335.

Coker AL, Smith PH, Thompson MP, McKeown RE, Bethea L, Davis KE. “Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health,” J. Womens Health Gend. Based Med., 2004;11(5) https://doi.org/10.1089/152460902601376.

Beeble ML, Bybee D, Sullivan CM, Adams AE. “Main, mediating, and moderating effects of social support on the well-being of survivors of intimate partner violence across 2 years,” Ournal Consult. Clin. Psychol., 2009;77(4) https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016140.

Borja SE, Callahan JL, Long PJ. “Positive and negative adjustment and social support of sexual assault survivors.,” J. Trauma. Stress, 2006;19(6) https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20169.

Bryant-Davis T et al., “Healing pathways: longitudinal effects of religious coping and social support on PTSD symptoms in African American sexual assault survivors.,” J. Trauma Dissociation, 2015;16(1) https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2014.969468.

Stark L, Landis D, Thomson B, Potts A. “Navigating support, resilience, and care: Exploring the impact of informal social networks on the rehabilitation and care of young female survivors of sexual violence in northern Uganda,” Peace Confl. J. Peace Psychol., 2016;22(3) https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000162.

Ullman SE. “Social support and recovery from sexual assault: a review,” Aggress. Violent Behav., 1999;4(3) https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-1789(98)00006-8.

Stark L, et al. Preventing violence against refugee adolescent girls: findings from a cluster randomised controlled trial in Ethiopia. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(5):e000825. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000825.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ Online. 2009;339(7716):332–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535.

WHO, “WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women,” 2005. [Online]. Available: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/24159358X/en/. Accessed 29 Nov 2021.

IASC, “Guidelines for Integrating Gender-based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Action,” Inter-Agency Standing COmmittee, 2015. [Online]. Available: http://gbvguidelines.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/2015-IASC-Gender-based-Violence-Guidelines_lo-res.pdf. Accessed 29 Nov 2021.

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, “Financial Tracking System,” 2020. https://fts.unocha.org/.

“Domestic Violence and Humanitarian Crises: Evidence from the 2014 Israeli Military Operation in Gaza - Catherine Müller, Jean-Pierre Tranchant, 2019.” https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801218818377?journalCode=vawa (accessed Jun. 01, 2022).

Keating C, Treves-Kagan S, Buller AM. “Intimate partner violence against women on the Colombia Ecuador border: a mixed methods analysis of the liminal migrant experience,” Confl. Health, 15(24) 2021, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-021-00351-y.

Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52:30–41.

Barrera M, Sandler IN, Ramsay TB. “Preliminary development of a scale of social support: studies on college students,” Am. J. Community Psychol., 1981;9(4) https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00918174.

Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, John K. “The assessment of social adjustment: an update,” Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 1981;38(11) https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780360066006.

Grootaert G, Narayan D, Nyhan Jones V, Woolcock M. Measuring Social Capital: An Integrated Questionnaire. World Bank Publications, 2004.

Cardoso LF, Gupta J, Shuman S, Cole H, Kpebo D, Falb KL. What factors contribute to intimate partner violence against women in urban, conflict-affected settings? Qualitative Findings from Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2016;93(2):364–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-016-0029-x.

Lilleston P, et al. Evaluation of a mobile approach to gender-based violence service delivery among Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(7):767–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czy050.

Treves-Kagan S, Peterman A, Gottfredson NC, Villaveces A, Moracco KE, Maman S, Treves-Kagan S, Peterman A, Gottfredson NC, Villaveces A, Moracco KE, Maman S. Love in the time of war: identifying neighborhood-level predictors of intimate partner violence from a longitudinal study in refugee-hosting communities. J Interpers Violence. 2021;37(11–12):1–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520986267.

Badurdeen FA. “Resolving trauma associated with sexual and gender-based violence in transcultural refugee contexts in Kenya,” in Health in Diversity – Diversity in Health: (Forced) Migration, Social Diversification, and Health in a Changing World, Springer VS, 2020, pp. 209–229.

Cardoso LF, Gupta J, Shuman S, Cole H, D. Kpebo H, Falb KL. “What factors contribute to intimate partner violence against women in urban, conflict-affected settings? Qualitative findings from Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire,” J. Urban Health Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med., 2016;93(2) https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-016-0029-x.

Kohli A, et al. Family and community driven response to intimate partner violence in post-conflict settings. Soc Sci Med. 2015;146:276–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.011.

Fellmeth G et al. “Prevalence and determinants of perinatal depression among labour migrant and refugee women on the Thai-Myanmar border: a cohort study,” BMC Psychiatry, 20(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02572-6.

Walstrom P, Operario D, Zlotnick C, Mutimura E, Benekigeri C, Cohen MH. “‘I think my future will be better than my past’: examining support group influence on the mental health of HIV-infected Rwandan women,” Glob. Public Health, 2013;8(1) https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2012.699539.

Brody C, et al. Economic self-help group programs for improving women’s empowerment: a systematic review. Campbell Syst Rev. 2015;11(1):1–182. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2015.19.

Cutrona CE, Russel DW. “Type of social support and specific stress: toward a theory of optimal matching,” in Social support: An interactional view, Oxford, England: John Wiley & Son, 1990, pp. 319–366.

Wang J, Mann F, Lloyd-Evans B, Ma R, Johnson S. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:156. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5.

Moss M, Frank E, Anderson B. “The effects of marital status and partner support on rape trauma,” Am. J. Orthopsychiatry, 1990;60(3) https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079179.

Davis RC, Brickman E, Baker T. “Supportive and unsupportive responses of others to rape victims: effects on concurrent victim adjustment,” Am. J. Community Psychol., 1991;19(3) https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00938035.

Arafa A. “Psychological correlates with violence against women victimization in Egypt,” Int. J. Ment. Health, 2021;50(1) https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.2020.1812819.

Masa’Deh R, AlMomani MM, Masadeh OM, Jarrah S, Al Ali N. “Determinants of husbands’ violence against women in Jordan,” Nurs. Forum (Auckl.), 2022;57(3) https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12700.

Classen CC, Palesh OG, Aggarwal R. Sexual revictimization. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2005;6(2):103–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838005275087.

Logie CH, et al. Social ecological factors associated with experiencing violence among urban refugee and displaced adolescent girls and young women in informal settlements in Kampala, Uganda: a cross-sectional study. Confl Health. 2019;13(1):60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-019-0242-9.

Silove D, Ventevogel P, Rees S. The contemporary refugee crisis: an overview of mental health challenges. World Psychiatry. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20438.

Koegler E et al. “Understanding how solidarity groups—a community-based economic and psychosocial support intervention—can affect mental health for survivors of conflict-related sexual violence in Democratic Republic of the Congo,” Violence Women, 2019;25(3) https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801218778378.

Ogbe E, Harmon S, Van den Bergh R, Degomme O. A systematic review of intimate partner violence interventions focused on improving social support and/ mental health outcomes of survivors. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(6):e0235177. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235177.

Horn R. “Responses to intimate partner violence in Kakuma refugee camp: refugee interactions with agency systems,” Soc. Sci. Med., 2010;70(1) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.036.

Al-Modallal H. “Patterns of coping with partner violence: experiences of refugee women in Jordan,” Public Health Nurs., 2012;29(5) https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1446.2012.01018.x.

Amone-P’Olak K et al. “Sexual violence and general functioning among formerly abducted girls in Northern Uganda: the mediating roles of stigma and community relations - the WAYS study,” BMC Public Health, 2016;16(61) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2735-4.

Betancourt TS, Brennan RT, Rubin-Smith J, Fitzmaurice GM, Gilman SE. “Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers: a longitudinal study of risk, protective factors, and mental health,” J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, 2010;49(6) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.03.008.

Cénat JM, Smith K, Morse C, Derivois D. “Sexual victimization, PTSD, depression, and social support among women survivors of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti: a moderated moderation model,” Psychol. Med., 50(15) https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719002757.

Fellmeth G, et al. Prevalence and determinants of perinatal depression among labour migrant and refugee women on the Thai-Myanmar border: a cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):168. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02572-6.

Logie CH, Okumu M, Mwima S, Hakiza R, Chemutai D, Kyambadde P. Contextual factors associated with depression among urban refugee and displaced youth in Kampala, Uganda: findings from a cross-sectional study. Confl Health. 2020;14:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-020-00289-7.

Müller C, Tranchant J-P. “Domestic violence and humanitarian crises: evidence from the 2014 Israeli Military Operation in Gaza,” Violence Women, 2019;25(12) https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801218818377.

Metheny N, Stephenson R. “Help seeking behavior among women who report intimate partner violence in Afghanistan: an analysis of the 2015 Afghanistan Demographic and Health Survey,” J. Fam. Violence, 2019;34(2) https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-018-0024-y.

Murphy M, Ellsberg M, Contreras-Urbina M. “Nowhere to go: disclosure and help- seeking behaviors for survivors of violence against women and girls in South Sudan,” Confl. Health, 2020;14(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-020-0257-2.

Okraku OO, Yohani S. “Resilience in the face of adversity: a focused ethnography of former girl child soldiers living in Ghana,” J. Int. Migr. Integr., 2021;22(3) https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-020-00769-y.

Verelst A, Bal S, De Schryver M, Kana NS, Broekaert E, Derluyn I. “The Impact of avoidant/disengagement coping and social support on the mental health of adolescent victims of sexual violence in Eastern Congo,” Front. Psychiatry, 2020;11(382) https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00382.

Wachter K, Murray SM, Hall BJ, Annan J, Bolton P, Bass J. “Stigma modifies the association between social support and mental health among sexual violence survivors in the Democratic Republic of Congo: implications for practice,” Anxiety Stress Coping, 2018;31(4) https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2018.1460662.

Weitzman A, Berhman JA. Disaster, disruption to family life, and intimate partner violence: the case of the 2010 Earthquake in Haiti. Sociol Sci. 2016;3:167–89. https://doi.org/10.15195/v3.a9.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank to Rachel Ding and Hannah Kluender for their support during the initial search article review phase.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was conceptualized by LS and MM. Article review and data extraction was conducted by IT, MM, and NT. Initial literature review was conducted by NT and MM. CP, IS, IT, LS, MM and NT were involved in original draft writing, editing, and final approval.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Meinhart, M., Seff, I., Lukow, N. et al. Examining the Linkage Between Social Support and Gender-Based Violence Among Women and Girls in Humanitarian Settings: a Systematic Review of the Evidence. Curr Epidemiol Rep 9, 245–262 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-022-00310-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-022-00310-y