Abstract

Purpose of Review

Firearm-related deaths are a significant source of mortality in the USA. More than 30,000 individuals die annually from firearm-related injuries, including homicide and suicide, in our nation. This review summarizes recent findings on policies designed to prevent illegal acquisition of firearms and their impacts on diversions of guns into underground markets and firearm-related homicide and suicide.

Recent Findings

A significant body of evidence has been produced between 2013 and 2018 demonstrating the effectiveness of laws requiring prospective handgun purchasers to obtain a permit (PTP). The evidence for other types of laws to deter illegal acquisition of firearms is less robust.

Summary

Current research on illegal acquisition and the impact of related policies illustrates that there are policies that effectively reduce diversion and have positive impacts on firearm-related violence. However, there is a paucity of research that use strong study designs and clearly identifies specific policy impacts pertaining to diversion and illegal acquisition of firearms. Future research is needed that further elucidates transactions that facilitate a gun’s entry into an underground market and the role and impact of policies regulating these transactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

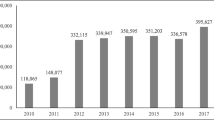

Firearms represent a significant burden of mortality in the USA. In 2016, there were 14,415 firearm homicides and 22,928 firearm suicides [1]. Firearm-related deaths accounted for nearly 8% of years of potential life lost in the USA before age 65 [2].

Because firearms are extremely lethal weapons, governments—both state and federal—have a vested interest in limiting access to firearms for certain subgroups within the overall population, e.g., individuals with a history of violence r serious criminal behavior, underage youth, or those undergoing a mental health crisis [3,4,5,6,7]. Laws and other policies are one means of limiting access. The purpose of this review is to summarize recent findings on the effectiveness of policies designed to prevent acquisition and diversion of firearms for illegal activities.

Numerous laws have been enacted with the goal of preventing or deterring the illegal acquisition of firearms by prohibited individuals with the ultimate goal of reducing crime and violence. The Brady Act established the National Instant Check System (NICS), which is used by law enforcement to conduct mandatory background checks of individuals attempting to purchase firearms from retail outlets. This federal law requires mandatory background checks of individuals seeking to purchase a firearm from federally licensed firearm retailers to determine whether a prospective purchaser meets requirements to legally purchase the firearm they seek to purchase. No such requirement exists for firearm sales by private parties. Several states have attempted to address the gap in federal law by developing their own laws to prevent private sales of firearms to prohibited individuals. Nineteen statesFootnote 1 and Washington, D.C. have comprehensive background check (CBC) laws requiring that prospective firearm purchasers pass a background check before a private seller can legally transfer a firearm. Nine of these 19 states have permit to purchase (PTP) laws that require that every prospective handgun purchaser—regardless of whether the seller is a licensed firearm dealer—obtain a permit or license directly from a law enforcement agency. Issuance of such as permit is contingent upon the prospective purchaser passing background checks and, in some states, mandatory firearm safety training. Additionally, at least 25 states have passed other laws that are specifically designed to prevent firearm trafficking including regulating licensed firearm dealers beyond the requirements of the federal government.

Methods

In this review, a comprehensive search was completed for literature published between 2013 and 2018 pertaining to underground gun markets and policies to curtail illegal gun acquisition in the USA. Searches were conducted in September 2018. Literature was gathered from PubMed, Criminal Justice Abstracts with Full Text, and NBER using the following search terms: “firearm trafficking,” “illegal gun market,” “straw purchase,” “firearm diversion,” “criminal firearm acquisition,” “universal background checks,” “comprehensive background checks,” “permit to purchase,” “licensing handgun purchasers,” “firearm theft,” “stolen firearms,” “firearm dealer regulation,” “firearm dealer compliance,” and “firearm dealer oversight.” Each term was searched by itself, without other qualifiers. It is also important to note that phrases which include the word “firearm” were re-searched with the word “gun” as a replacement for “firearm.” We also examined the bibliography of the RAND Corporation Study on Gun Violence and included articles known by the authors to be relevant to this topic. The result was 102 articles total from the databases searched, which were imported into DistillerSR for screening. Of the 102 articles, 55 were excluded after a screening of titles, and of the remaining 47 articles, 13 were excluded upon abstract examination. Out of the 34 articles included in the review, 11 articles discussed underground gun markets and illegal gun acquisition, 6 articles discussed policies to address illegal gun acquisition, and 17 articles examined the effects of such policies on health outcomes.

Underground Market and Illegal gun Acquisition

Researchers have long sought to understand how criminals obtain guns and how guns are diverted from the legal to the illegal market. Between 2013 and 2018, 11 articles examined the underground market for firearms and patterns of illegal gun acquisition (Table 1). Five of the 11 articles describe where offenders get their guns and why. Two articles focused specifically on the role of gun theft in providing guns for criminal use. Two articles examined illegal firearm sales, and the remaining two examined the limited role of cryptomarkets in the sale of firearms.

The researchers used several approaches to determine where and how offenders obtain firearms. Some used crime gun trace data and law enforcement data to describe the characteristics of firearms used in crimes. A study of crime gun trace data from Chicago found that guns confiscated from gang members were generally old and, therefore, likely to have gone through many transactions [8]. It was rare for a crime gun to have been recently purchased from a licensed dealer. Intermediaries—acquaintances, friends, family—played a much larger role than licensed dealers as proximal sources. Investigations of the origins of relatively old crime guns and the prosecution of those who make illegal transfers years prior to the gun’s recovery in criminal use are very challenging. Thus, the study’s authors suggest that law enforcement should focus on straw purchasers and trafficking relatively soon after retail sale [8]. (A “straw purchase” is the illegal purchase of firearm on behalf of another person who cannot legally purchase one or otherwise does not want their name associated with the transaction). A study of guns purchased from retailers in 1990s and subsequently recovered by Baltimore police found they were more likely than guns that were not linked to crime to be semiautomatic, larger caliber, easily concealed, inexpensive, purchased by individuals that had previously purchased guns recovered by law enforcement, and sold by dealers who had previously sold crime guns [9]. These two studies are somewhat limited by their use of crime gun trace data. The information obtained on transfers is usually limited to the retail transaction by the licensed retail seller to the initial retail purchaser as well as information about the crime linked to the firearm and its criminal possessor.

Some researchers have explored the general character of the crime gun market by asking inmates about how they obtained their guns and why they felt they needed a firearm. A survey of inmates in Chicago found that most guns were acquired from an offender’s social network rather than from a store or through theft [10]. While most respondents indicated that they purchased or acquired their gun in a trade, some offenders were caught with a gun they were sharing with others or that they were holding for someone else. Importantly, survey respondents reported favoring their social networks because purchasing from strangers elevated the risk of arrest [10]. A similar study from Boston found that guns possessed by gang members, in comparison to other crime guns, were more likely to be older and to originate from an out-of-state retail sale [12]. A survey of gun offenders in Los Angeles found that offenders’ social connections were far more important than were firearm brokers (those who charged a fee for connecting individuals with illegal suppliers of firearms) [11]. Though these studies provide important insight into the underground gun market, they may be limited in their generalizability to other cities, states, or regions.

Theft is often hypothesized as being an important method by which criminals acquire guns. A study of guns recovered by police in Chicago found that less than 3% of crime guns had previously been reported stolen [12]. Surveys of Chicago gun offenders also indicated that offenders very rarely steal the guns they used to commit crimes [12]. Data from a nationally representative sample of inmates in state prisons in 2004 found that 10% of those who committed crimes with guns reported that they had stolen the gun they used [13]. While it is still possible that stolen guns end up on the criminal market, it appears that theft of a gun does not usually immediately precede a criminal act with a gun by the thief. A nationally representative survey asked gun owners about gun theft and found that gun owners were more likely to have their guns stolen if they owned six or more guns, carried guns in public, store their guns in an unsafe manner, and stated that they owned guns for protection [14].

If theft plays a relatively small role in direct criminal firearm use, illegal transfers (including those post-theft) likely play a large role. One study from 2013 surveyed licensed dealers and pawnbrokers about straw purchases, undocumented purchases, and theft. Dealers reported that attempts to acquire firearms illegally were quite common—67.3% of respondents had experienced an attempted straw purchase at their establishment and 42.4% had experienced individuals attempting to complete an undocumented purchase [15]. A similar study from 2017 sought to examine the other side of firearm transactions, surveying gun owners to determine where they obtained their most recent firearm. Half of gun owners stated that they had acquired their most recent firearm in a private transfer without a background check. The proportion was nearly halved in states that regulated these private sales [16]. It remains unclear, however, how much these surveys reveal about the way guns used in crimes are acquired. Surveys of inmates and gang members reveal that the most trusted sources of firearms are members of their social networks.

Another oft-hypothesized source of firearms is the Internet. Cryptomarkets—online marketplaces on the “darknet” that enable users to trade illegal goods—are one potential source for firearms. A 2017 study seeking to describe the structure of illegal trafficking on cryptomarkets noted that firearms were available on some of these sites, but traders tended to focus on drugs [17]. A more recent study focused specifically on firearms, extracting webpages from nine cryptomarkets to describe how weapons were trafficked on these sites. The researchers found that weapons were a very small proportion of the illegal trafficking occurring on these sites. Even within the broader weapons category, firearms only accounted for 25% of sales. In truth, the authors argue, cryptomarket firearm transactions are somewhat limited and tend to be exaggerated [18]. This further supports the idea that unregulated private transactions within social networks may be a larger contributor to the underground gun market.

Policies to Deter Illegal Acquisition and Impacts on Diversion

To limit illegal gun acquisition and hamper the underground gun market, state legislatures have implemented policies designed to deter illegal transfers and acquisitions of firearms. As noted above, these policies include private transfer background check laws (CBC), laws requiring prospective handgun purchasers to obtain a license (PTP), those focusing on firearm trafficking, and state regulation of firearm dealers. Most states, however, have not enacted these laws [19, 20].

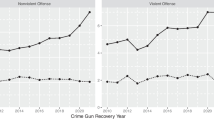

Between 2013 and 2018, six articles examined aspects of the relationship between policies to deter illegal acquisition and their intended target, diversion of guns to criminal markets (Table 2). Two of these studies [19, 20] focus on describing current and historic state laws. Three articles focus explicitly on the intended outcome of these laws—the diversion of guns from the legal market to the underground, illegal market [21,22,23]. One study examined data on prosecutions for violating CBC laws in Maryland and Pennsylvania and revealed that individuals were rarely charged with violating CBC laws. There was a dramatic increase in prosecutions for violating Pennsylvania’s law against straw purchases of guns after state lawmakers increased penalties for straw purchases and a sharp decline in CBC prosecutions in Maryland following a court ruling that significantly elevated standards of proof for CBC violations [24•]. The findings suggest that available penalties and standards for evidence required likely affect decisions to investigate and prosecute offenders of laws designed to prevent illegal gun transfers. More research is needed on the frequency with which individuals are prosecuted for violating CBC or related laws, factors that influence decisions to investigate and prosecute such violations, and the impact of enhanced enforcement of the laws. In addition, more research is needed on the implementation and enforcement of PTP laws.

The two studies that examined state laws intended to deter illegal firearm acquisition focused on policies to keep guns away from individuals at the highest risk of committing a criminal act, harming others, or harming themselves [19, 20]. One team of researchers published a large database of firearm laws in place between 1991 and 2016. This database is useful for researchers seeking to evaluate the effect of state law changes. In presenting their database, however, the researchers do not present an appropriately nuanced analysis of these laws, opting instead to compare the number of firearm laws in each state [20]. Few policy implications can be drawn from this analysis; however, the database can be used to more fully characterize the legal environment under which firearms are sold and coupled with rigorous statistical methods to generate important research findings.

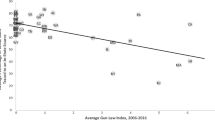

Recent evaluations of state firearm laws have found that strict laws governing private transfers can limit the ability of criminals to acquire guns. An analysis of firearms traced by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) revealed that in states with the strictest laws on firearm transfers and dealer regulations, the firearms used in crime were less likely to have moved swiftly from retail sale to criminal use than was the case in states with weaker gun sales laws. One study found that the broad set of regulations in place in California were associated with the longest interval between gun sales and crime involvement and that PTP laws, especially when coupled with firearm registration requirements, were linked with gun used in crime being older [21]. A study of Massachusetts crime guns found that crime guns moved quickly from private transfer to law enforcement recovery, but most trace data was unavailable to Massachusetts investigators because it was not recorded or reported correctly [22]. A 50-state analysis of recent gun trace data found that four laws were independently associated with decreases in the percentage of guns traced to an in-state source: handgun waiting periods, PTP, violent misdemeanor prohibitions, and a requirement that firearms be relinquished by those who became prohibited from possessing them [23].

One paper found that enforcement and implementation of firearm laws deserve more attention. The study examined gun law prosecutions in two states with CBC laws and found that enforcement of firearm laws is affected by the penalties associated with violating the law and judicial interpretation of the underlying statutes [24•]. This suggests that states with CBC laws must invest more heavily in enforcement and implementation of those laws and that stronger laws may prompt stronger enforcement. More research is necessary to determine whether prosecutions for these crimes and stiff penalties for violators are associated with changes in the criminal firearm market.

In addition to the research described here, additional work is needed to fully elucidate the relationship between policies intended to deter illegal acquisition and the diversion of guns to criminal markets. Perhaps the most important issue underlying this relationship is restrictions on access to crime gun trace data nationally over a span of many years. In 2003, the federal Tiahrt Amendment restricted access to granular crime gun trace data nationally by researchers or others and prohibited use of these data in regulatory decisions (e.g., license renewal) or litigation. Because data are keys to most systems of accountability, the Tiahrt Amendment may have weakened accountability of gun sellers. Prior research has shown that these changes were associated with increased diversion of guns to the criminal market [25]. Firearm trace data is an important resource for researchers seeking to determine the origin of guns used in criminal acts. Without these data, it is very difficult to evaluate the specific effects of policies intended to inhibit the illegal transfer and acquisition of firearms.

Impact on Health Outcomes of Policies to Deter Illegal Acquisition

Polices that are designed to prevent illegal acquisition of firearms may also have downstream impacts on health outcomes such as homicide and suicide. Between 2013 and 2018, 17 articles examined the relationship between policies to deter illegal acquisition and firearm-related death (Table 3). All but one of the studies [26•] explored the effects of these policies at the state level. Ten of the 16 studies were longitudinal (or time series) [26•, 27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34, 35•], five used a cross-sectional design [36,37,38,39,40], and two were systematic review articles [41, 42]. Eight articles focused on the outcome of firearm homicide [26•, 27,28,29, 34, 35, 40, 42], five on firearm suicide [30, 32, 36,37,38], and one examined both [33]. One paper focused on the outcome of firearm injury [41]. Additionally, one paper examined police officers killed in the line-of-duty [31] and one looked at police killings of civilians [39]. The studies evaluated a range of policies to deter illegal acquisition including PTP, CBC, trafficking, and state regulation of firearm dealers. A challenge is that researchers often combined PTP and CBC laws together in their evaluation, although they are distinct policies, which makes the interpretation of the evidence on CBC laws less clear.

Five studies specifically examined PTP laws; four were longitudinal and one was cross-sectional. Two longitudinal studies examined the effects of Missouri repealing its PTP law but used analytic approaches. Each found evidence that Missouri’s PTP law had been protective against firearm homicide [27, 35•]. Another longitudinal study estimated the effects of Connecticut’s PTP law and found a relatively large association between the law and reduced rates of firearm homicide [29]. Crifasi et al. studied state-level variation in on-duty fatalities and assaults of law enforcement officers and found PTP law effects suggestive of protections against handgun assaults against police officers [31]. Additionally, one longitudinal paper found PTP to be protective against firearm suicide [30]. The one cross-sectional paper looking specifically at PTP found the laws to be associated with lower firearm suicide [36].

One longitudinal study examined both PTP and CBC and found that while PTP was associated with reductions in firearm homicide, laws requiring CBC without PTP did not show a clear beneficial impact [26•]. Specifically, CBC laws were associated with higher rates of firearm homicides in the main models, but analyses that included 1-, 2-, and 3-year lead and lag variables for CBC laws indicated that firearm homicide rates were increasing with each year approaching the introduction of a new CBC law and then stabilized in the years after CBC laws were in effect. Two other longitudinal studies examining CBC found no protective effects of CBC law against firearm homicide [33, 34]. One also explored firearm suicide and did not find beneficial effects of California’s CBC law [33]. This contrasts with one longitudinal and two cross-sectional studies that found protective effects. The longitudinal paper found slower increases in firearm suicide among states with CBC laws [32], and the two cross-sectional studies found lower firearm suicide among states with CBC laws [37, 38]. However, not all the studies finding protective effects appropriately differentiated between states with PTP versus those with only CBC. These results are difficult to interpret and may be due to the impact of PTP laws rather than CBC alone. An additional cross-sectional study explored numerous laws’ impacts on firearm mortality and found protective effects of CBC laws [40]; however, the quality of the study design and estimates suggesting that a law that has not yet been implemented had huge protective effects on firearm mortality call into question the validity of the findings.

One study found that laws requiring firearm dealers to obtain state licenses that allowed for law enforcement inspections of firearm sales records were associated with lower firearm homicide rates after controlling for levels of gun ownership and other factors [28]. A limitation of this study was that the laws in question did not change during the study period, thus preventing researchers from linking changes in homicides to changes in laws. Finally, a cross-sectional study found that scores for the restrictiveness of firearm laws, specifically the robustness of backgrounds including whether a PTP is required and anti-gun-trafficking laws, were negatively associated with police fatally shooting civilians [39].

Two systematic reviews were published during our review period that explored the impact of policies to deter illegal acquisition and firearm-related deaths. One found that PTP laws were associated with decreases in firearm mortality [41]. The other review found evidence that stronger CBC laws and PTP laws were associated with lower rates of firearm homicide; however, the authors do not note that the studies linking stronger background checks laws with lower firearm homicide rates were cross-sectional and that PTP laws were weighted contributors to the background check scales [42]. In contrast, protective effects of PTP laws were based on estimates of change over time relative to changes in non-PTP comparison states. This review also notes that neither of the two studies examining the effects of prohibitions on buying more than one firearm per month per person found protective effects against homicides [42].

Social Acceptability of Laws to Deter Illegal Acquisition of Firearms

Laws intended to deter the illegal acquisition of firearms are popular among both the public and firearm retailers. Respondents to a nationally representative survey overwhelmingly supported laws requiring background checks for private sales (87.8%) and laws requiring accountability for firearm retailers unable to account for missing or stolen firearms (84.8%). Support for these laws was similar among gun owners and those not owning guns [43]. A separate survey found that the majority (72%) of the public agrees that it is unacceptable for someone to sell a gun to a stranger without a background check [44]. Notably, however, this survey did not ask how respondents felt about transfers between acquaintances or family members and did not distinguish between differences in background check systems for CBC versus PTP laws. A survey of federally licensed firearm dealers showed moderate support for private sale background check laws, particularly if they are exposed to illegal activities like individuals attempting to purchase firearms illegally. The surveyed dealers were more supportive of laws outlining specific criteria for denial of handgun purchase, including criminal history, excessive alcohol use, and mental health issues. Again, this survey did not differentiate for dealers between background check systems with CBC versus PTP [45]. While this survey was not representative of all dealers, it contributes to the overall conclusion that laws designed to deter illegal firearm acquisition generally enjoy widespread support.

Conclusions

Recent research on the effectiveness of permit to purchase (PTP) laws designed to prevent the illegal acquisition of firearms provides strong evidence that these laws reduce the diversions of guns into the underground market, firearm homicides, and firearm suicides. There is also some evidence to suggest that these laws protect against police-involved shootings and assaults against law enforcement officers. While cross-sectional studies find that comprehensive background check (CBC) laws and stronger overall background check systems are associated with lower rates of firearm mortality, longitudinal studies examining the effects of changes in CBC laws have yet to demonstrate that these laws reduce firearm mortality rates. Completeness of records on prohibiting conditions that are used for pre-sale background checks [46] and limited enforcement [25] may weaken compliance with the laws and their impacts on public safety outcomes.

Weaknesses in US Federal laws governing licensed gun sellers and resource constraints for regulatory oversight create conditions that allow large volumes of firearms to be diverted for criminal use [47, 48]. Some states augment federal regulations and oversight with their own licensing and oversight practices. Although there have not been recent changes in these laws to estimate the effects in longitudinal analyses, after controlling for other factors, states that require firearm dealer licensing and compliance inspections have lower firearm homicides than states lacking those laws.

This review illustrates the effectiveness of policies designed to deter illegal acquisition of firearms. However, it also highlights the relative paucity of research being conducted that uses strong study designs and clearly identifies policy impacts to determine their effectiveness. Only 34 relevant articles were published between 2013 and 2018. Many of these studies examine cross-sectional associations and do not attempt to isolate the impact of changes in specific firearm laws. None of the studies identified used data that distinguished legal versus unlawful purchasers and possessors of firearms based on the laws in place. This is likely a product of challenges in accessing relevant data and limited funding available to evaluate gun policy. Another challenge to this body of research is that there have not been many changes in certain kinds of laws designed to keep guns from legally prohibited individuals (e.g., state licensing and oversight of retail firearm sellers, PTP laws). Given the substantial public health magnitude of firearm-related injury, there is a pressing need to improve the quantity and quality of the research on this topic.

Notes

Nevada currently has a law requiring a background check for private sales, but it has yet to be implemented

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

CDC. WISQARS - Fatal injury reports, national, regional and state, 1981-2016. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018. https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate.html. Accessed June 2018.

CDC. WISQARS years of potential life lost (YPLL) report, 1981 and 2016. 2017. https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/ypll.html. Accessed June 2018.

Azrael D, Hepburn L, Hemenway D, Miller M. The stock and flow of US firearms: results from the 2015 National Firearms Survey. RSF: Russell Sage Found J Social Sci. 2017.

Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. Household firearm ownership and suicide rates in the United States. Epidemiology. 2002;13(5):517–24.

Miller M, Azrael D, Hepburn L, Hemenway D, Lippmann SJ. The association between changes in household firearm ownership and rates of suicide in the United States, 1981–2002. Inj Prev. 2006;12(3):178–82.

Kellermann AL. Guns and homicide in the home. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(13):928–9.

Kellermann AL, Rivara FP, Somes G, Reay DT, Francisco J, Banton JG, et al. Suicide in the home in relation to gun ownership. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(7):467–72. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199208133270705.

Cook PJ, Harris RJ, Ludwig J, Pollack HA. Some sources of crime guns in Chicago: dirty dealers, straw purchasers, and traffickers. J Crim L Criminol. 2014;104:717.

Koper CS. Crime gun risk factors: buyer, seller, firearm, and transaction characteristics associated with gun trafficking and criminal gun use. J Quant Criminol. 2014;30(2):285–315.

Cook PJ, Parker ST, Pollack HA. Sources of guns to dangerous people: what we learn by asking them. Prev Med. 2015;79:28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.04.021.

Chesnut KY, Barragan M, Gravel J, Pifer NA, Reiter K, Sherman N, et al. Not an ‘iron pipeline’, but many capillaries: regulating passive transactions in Los Angeles’ secondary, illegal gun market. Inj Prev. 2017;23(4):226–31.

Cook PJ. Gun theft and crime. J Urban Health. 2018;95(3):305–12.

Webster D, Vernick J, McGinty E, Vittes K, Alcom T. Preventing the diversion of guns to criminals through effective firearm sales Laws. In: Webster D, Vernick J, editors. Reducing gun violence in America: informing policy with evidence and analysis. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2013. p. 109–22.

Hemenway D, Azrael D, Miller M. Whose guns are stolen? The epidemiology of gun theft victims. Inj Epidemiol. 2017;4(1):11.

Wintemute GJ. Frequency of and responses to illegal activity related to commerce in firearms: findings from the Firearms Licensee Survey. Inj Prev. 2013;19(6):412–20.

Miller M, Hepburn L, Azrael D. Firearm acquisition without background checks: results of a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(4):233–9.

Broséus J, Rhumorbarbe D, Morelato M, Staehli L, Rossy Q. A geographical analysis of trafficking on a popular darknet market. Forensic Sci Int. 2017;277:88–102.

Rhumorbarbe D, Werner D, Gilliéron Q, Staehli L, Broséus J, Rossy Q. Characterising the online weapons trafficking on cryptomarkets. Forensic Sci Int. 2018;283:16–20.

Vernick JS, Alcorn T, Horwitz J. Background checks for all gun buyers and gun violence restraining orders: state efforts to keep guns from high-risk persons. J Law Med Ethics. 2017;45:98–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073110517703344.

Siegel M, Pahn M, Xuan Z, Ross CS, Galea S, Kalesan B et al. Firearm-Related Laws in All 50 US States, 1991-2016. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(7):1122–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2017.303701.

Pierce GL, Braga AA, Wintemute GJ. Impact of California firearms sales laws and dealer regulations on the illegal diversion of guns. Injury Prevention. 2015;21(3):179–84.

Braga AA, Hureau DM. Strong gun laws are not enough: the need for improved enforcement of secondhand gun transfer laws in Massachusetts. Prev Med. 2015;79:37–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.05.018.

Collins T, Greenberg R, Siegel M, Xuan Z, Rothman EF, Cronin SW, et al. State firearm laws and interstate transfer of guns in the USA, 2006–2016. J Urban Health. 2018;95(3):322–36.

• Crifasi CK, Merrill-Francis M, Webster DW, Wintemute GJ, Vernick JS. Changes in the legal environment and enforcement of firearm transfer laws in Pennsylvania and Maryland. Inj Prev. 2018; injuryprev-2017-042582. https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042582. First study to examine whether state laws related to the transfer of firearms were being enforced. Enforcement significantly associated with strength of penalities and interpretation of the law.

Webster DW, Vernick JS, Bulzacchelli MT, Vittes KA. Temporal association between federal gun laws and the diversion of guns to criminals in Milwaukee. J Urban Health. 2012;89(1):87–97.

• Crifasi CK, Merrill-Francis M, McCourt A, Vernick JS, Wintemute GJ, Webster DW. Association between firearm laws and homicide in urban counties. J Urban Health. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-018-0273-3. Longitutinal study evaluting the impact of laws on firearm homicide in urban areas. PTP laws associated with reductions, RTC and SYG with increases, and CBC and VM laws no effective of effect on firearm homicides.

Webster DW, Crifasi CK, Vernick JS. Effects of the repeal of Missouri’s handgun purchaser licensing law on homicides. J Urban Health. 2014;91:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-014-9865-8.

Irvin N, Rhodes K, Cheney R, Wiebe D. Evaluating the effect of state regulation of federally licensed firearm dealers on firearm homicide. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(8):1384–6.

Rudolph KE, Stuart EA, Vernick JS, Webster DW. Association between Connecticut’s permit-to-purchase handgun law and homicides. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):e49–54.

Crifasi CK, Meyers JS, Vernick JS, Webster DW. Effects of changes in permit-to-purchase handgun laws in Connecticut and Missouri on suicide rates. Prev Med. 2015;79:43–9.

Crifasi CK, Pollack KM, Webster DW. Effects of state-level policy changes on homicide and nonfatal shootings of law enforcement officers. Injury prevention. 2016;22(4):274–8.

Anestis MD, Selby EA, Butterworth SE. Rising longitudinal trajectories in suicide rates: the role of firearm suicide rates and firearm legislation. Prev Med. 2017;100:159–66.

Kagawa RM, Castillo-Carniglia A, Vernick JS, Webster D, Crifasi C, Rudolph KE, et al. Repeal of comprehensive background check policies and firearm homicide and suicide. Epidemiology. 2018;29(4):494–502.

Gius M. The effects of state and federal background checks on state-level gun-related murder rates. Appl Econ. 2015;47(38):4090–101.

• Hasegawa RB, Webster DW, Small DS. Evaluating Missouri’s Handgun Purchaser Law: A Bracketing Method for Addressing Concerns About History Interacting with Group. Epidemiology. 2019;30(3):371–9. Longitudinal study using bracketing. The repeal of Missouri’s PTP laws associated with significant increases in firearm homicide.

Anestis MD, Khazem LR, Law KC, Houtsma C, LeTard R, Moberg F, et al. The association between state laws regulating handgun ownership and statewide suicide rates. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):2059–67.

Anestis MD, Anestis JC. Suicide rates and state laws regulating access and exposure to handguns. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):2049–58.

Anestis MD, Anestis JC, Butterworth SE. Handgun legislation and changes in statewide overall suicide rates. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(4):579–81.

Kivisto AJ, Ray B, Phalen PL. Firearm legislation and fatal police shootings in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(7):1068–75.

Kalesan B, Mobily ME, Keiser O, Fagan JA, Galea S. Firearm legislation and firearm mortality in the USA: a cross-sectional, state-level study. Lancet. 2016;387(10030):1847–55.

Crandall M, Eastman A, Violano P, Greene W, Allen S, Block E, et al. Prevention of firearm-related injuries with restrictive licensing and concealed carry laws: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(5):952–60.

Lee LK, Fleegler EW, Farrell C, Avakame E, Srinivasan S, Hemenway D, et al. Firearm laws and firearm homicides: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):106–19.

Barry CL, Webster DW, Stone E, Crifasi CK, Vernick JS, McGinty EE. Public support for gun violence prevention policies among gun owners and non-gun owners in 2017. Am J Public Health. 2018;108:e1–4. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304432.

Hemenway D, Azrael D, Miller M. Selling a gun to a stranger without a background check: acceptable behaviour? Injury Prevention. 2018;24(3):213–7.

Wintemute GJ. Support for a comprehensive background check requirement and expanded denial criteria for firearm transfers: findings from the Firearms Licensee Survey. J Urban Health. 2014;91(2):303–19.

DeBacco D, Schauffler R, SEARCH-National Consortium for Justice Information and Statistics, and United States of America. State Progress in Record Reporting for Firearm-related Background Checks: Fugitives from Justice. BJS [National Criminal Justice Reference Service]; 2017.

Webster DW, Wintemute GJ. Effects of policies designed to keep firearms from high-risk individuals. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:21–37.

Vernick J, Webster D. Curtailing dangerous practices by licensed firearm dealers: legal opportunities and obstacles. In: Webster D, Vernick J, editors. Reducing gun violence in America: informing policy with evidence and analysis. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2013. p. 133–42.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Injury Epidemiology

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Crifasi, C.K., McCourt, A.D., Booty, M.D. et al. Policies to Prevent Illegal Acquisition of Firearms: Impacts on Diversions of Guns for Criminal Use, Violence, and Suicide. Curr Epidemiol Rep 6, 238–247 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-019-00199-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-019-00199-0