Abstract

Background

Prescription drug misuse is a growing public health concern globally. Routinely collected data provide a valuable tool for quantifying prescription drug misuse.

Objective

To synthesize the global literature investigating prescription drug misuse utilizing routinely collected, person-level prescription/dispensing data to examine reported measures, documented extent of misuse and associated factors.

Methods

The MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, MEDLINE In Process, Scopus citations and Google Scholar databases were searched for relevant articles published between 1 January 2000 and 31 July 2013. A total of 10,803 abstracts were screened and 281 full-text manuscripts were retrieved. Fifty-two peer-reviewed, English-language manuscripts met our inclusion criteria—an aim/method investigating prescription drug misuse in adults and a measure of misuse derived exclusively from prescription/dispensing data.

Results

Four proxies of prescription drug misuse were commonly used across studies: number of prescribers, number of dispensing pharmacies, early refills and volume of drugs dispensed. Overall, 89 unique measures of misuse were identified across the 52 studies, reflecting the heterogeneity in how measures are constructed: single or composite; different thresholds, cohort definitions and time period of assessment. Consequently, it was not possible to make definitive comparisons about the extent (range reported 0.01–93.5 %), variations and factors associated with prescription drug misuse.

Conclusions

Routine data collections are relatively consistent across jurisdictions. Despite the heterogeneity of the current literature, our review identifies the capacity to develop universally accepted metrics of misuse applied to a core set of variables in prescription/dispensing claims. Our timely recommendations have the potential to unify the global research field and increase the capacity for routine surveillance of prescription drug misuse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Prescription drug misuse is increasing globally. This can be readily monitored using routinely collected data to quantify drug access patterns at the population-level. |

Our review identified only four common proxies for prescription drug misuse (number of prescribers, number of dispensing pharmacies, volume of drug(s) dispensed and/or overlapping prescriptions/early refills); however, these proxies were used to derive 89 unique definitions of misuse due to variations in thresholds or measures (single or multiple behavior measures). |

We recommend the development of consistent and replicable metrics to facilitate monitoring and comparisons of the extent of prescription drug misuse across healthcare settings and over time. |

1 Introduction

Research demonstrates a high degree of variability in how drugs are prescribed and used [1]. Drugs including sedatives, anxiolytics, analgesics and stimulants are often taken excessively to enhance desired effects [1]. The consequences of excessive use are a major public health concern and include drug tolerance [2, 3], increased risk of side effects [3–5], overdose [6], dependence [7], hospitalization [5] or death [2, 8, 9]. These risks are escalated with concomitant prescription drug, alcohol or illicit drug use [10–16].

Research methodologies, including medical chart [17], surveys [18], qualitative [19, 20] and observational studies [21], have been used to explore prescription drug misuse. In recent decades, the growing availability of routinely collected health information has increased opportunities to undertake population-based surveillance of prescription drugs. The evidence generated from routinely collected data can further enhance our understanding of prescription drug misuse, patient and prescriber behavior outcomes of misuse, and influence policy changes on these issues.

There are no universally accepted definitions of prescription drug misuse [22, 23] making quantification challenging. Due to the limited clinical information held in routine data collections, prescription drug misuse is not directly measured at the population level [23] but is commonly inferred based on patterns of drug access and by investigating patient interactions with prescribers and pharmacies.

In response to concerns about the management of chronic pain treated with opioid analgesics, the US FDA has recently sought submissions related to the post-market surveillance of extended release and long-acting opioid formulations [24]. In particular, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requested submissions relating to defining misuse, abuse, addiction and their consequences measured in routine data collections [24]. Clearly, synthesizing the global literature will add significant value to this endeavor.

Our timely systematic review aims to examine the measures, extent and factors associated with prescription drug misuse in observational studies based on routinely collected person-level prescription or dispensing data.

2 Methods

2.1 Eligible Studies

The review included English-language, peer-reviewed manuscripts published between 1 January 2000 and 31 July 2013, which satisfied the following criteria:

-

the aim or method investigated prescription drug misuse;

-

measure of prescription drug misuse derived exclusively from person-level prescription/dispensing data;

-

investigated misuse in adult persons (≥18 years).

Grey literature (government reports), case reports, letters, editorials, opinion pieces, reviews and conference abstracts were excluded.

2.2 Study Identification

2.2.1 Search Strategy (Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] 1)

A search was conducted of the MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and MEDLINE In Process databases combining keywords and subject headings to identify studies investigating prescription drug misuse measured in routinely collected prescription/dispensing data using observational approaches. Search terms included misuse, problematic; prescription drugs; factual databases; population surveillance, cohort studies. Three further searches were completed using Google Scholar [25] (reviewed first 200 results per search), Scopus citations (for articles citing included manuscripts) and screened back references of included studies, review articles and selected excluded studies.

Two reviewers (BB and LM) screened the abstracts and titles of articles to identify potentially relevant studies. These studies were assessed independently (BB and LM) for inclusion in the review using a five-item tool based on the eligibility criteria (ESM 2). A third reviewer (SP) arbitrated when consensus about inclusion was not reached (18 % of articles).

2.3 Data Extraction

Two independent reviewers (BB and LM) completed comprehensive data extraction for articles meeting our eligibility criteria (ESM 3), with the following information being extracted:

-

1.

Study characteristics: year of publication; publishing journal; observation period (beginning and end year, and duration in months); funding source; objectives; setting; generic names of drug(s) investigated; data source, including extent of population coverage, and terminology related to misuse. We also calculated lag time (year of publication minus last year of observation).

-

2.

Cohort characteristics: number of cohort(s); cohort size(s); and cohort details, including study inclusion/exclusion criteria. Studies reported the extent of prescription drug misuse in drug-user cohorts (persons dispensed or prescribed the drug[s] of interest) or in misuse cohorts (persons exhibited behavior considered to be above the norms of prescription drug use).

-

3.

Measures of prescription drug misuse: the characteristic or behavior of interest (e.g. number of prescribers), threshold defining behavior indicative of misuse as defined by the study authors (e.g. ≥4 prescribers) and time period of assessment (e.g. 6 months).

Each measure was identified as follows:

-

stand-alone investigated a single characteristic or behavior (e.g. the proportion of persons accessing ‘≥4 prescribers’ in 6 months); or

-

composite in drug-user cohorts, the measurement of two or more characteristics or behaviors (e.g. the proportion of persons using ‘≥4 prescribers AND ≥4 dispensing pharmacies’ in 6 months). In misuse cohorts (e.g. defined by persons using ‘≥4 prescribers’ in 6 months) the measurement of at least one additional characteristic or behavior (e.g. the proportion of misusers accessing ‘≥4 dispensing pharmacies’ in 6 months).

-

-

4.

Other prescription drug misuse-related outcomes, e.g. specific drug classes and drugs associated with misuse.

-

5.

Summary statistics: percentages or other statistics (e.g. means with standard deviation or medians with ranges) related to all misuse measures. Where possible, we calculated the extent of misuse in user cohorts if not reported in individual studies.

-

6.

Rationale for measure(s) of misuse: any reference to previously published studies; expert panel recommendations; empirical derivation, or any other rationale.

-

7.

Comprehensiveness of reporting (BB only) according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement Checklist for Observational, Population-Based Cohort Studies [26, 27].

2.4 Terminology

In the global literature, a range of terms are used to encapsulate prescription drug misuse including abuse, dependence, diversion, misuse, problematic or non-medical use [1, 28–30]. As such, our search strategies included 24 unique misuse-related terms to capture relevant articles. For the purposes of this review, we use the umbrella term ‘prescription drug misuse’ to capture the continuum of misuse, ranging from use above the norms, through to dependence, abuse and diversion. This is consistent with the FDA’s terminology in their recent call for submissions on post-market opioid surveillance [24].

2.5 Analysis

In reviewed studies there was considerable variation in study design including: study population(s), drug(s) of interest, definition(s) of misuse and outcome measures. Due to this variation, it was not possible or appropriate to use traditional meta-analytic approaches to pool individual study results. Instead, we provided a descriptive analysis, detailed the key findings of individual studies and summarized study features in tables and figures. Our review is consistent with AMSTAR (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews) and PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) reporting criteria (ESM 4).

3 Results

3.1 Studies Identified

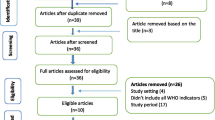

The titles/abstracts of 10,803 articles were screened and 281 full-text manuscripts were reviewed. Fifty-two studies met our eligibility criteria; 38 were identified from MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL or MEDLINE In Process, 2 from Google Scholar, 4 from Scopus citations and 8 from back references (Fig. 1). The bibliography of the 229 excluded and 52 included studies are detailed in ESM 5 and 6, respectively.

3.2 Study Features (Table 1; ESM 7)

The studies were set in the US (27 studies), France (17 studies), Norway (seven studies) or Canada (one study). All studies from Norway used dispensing data for the entire national population; the remaining 45 studies used populations within a specific province, state or region. Of the 52 included studies, 32 (61.5 %) were published between 2010 and July 2013. The median study observation period was 18 months (range 4–132 months; interquartile range [IQR] 12–37.5 months) and the median lag time was 4 years (range 2–15 years; IQR 3–6 years). Twenty-one studies did not report a funding source, and the remaining studies were funded primarily by research grants (15 studies) or the pharmaceutical industry (seven studies). Fifty-one studies utilized dispensing data; one study used prescription data. Forty-six unique terms were used by study authors to encapsulate the concept of ‘prescription drug misuse’ (Box 1).

3.4 Measures of Prescription Drug Misuse (Table 2; ESM 8)

Fifty studies defined a measure with a specific misuse threshold (e.g. ≥4 prescribers). Overall, four behaviors were the basis of the misuse measures, either alone or in combination: number of prescribers, number of dispensing pharmacies, volume of drug(s) dispensed and/or overlapping prescriptions/early refills.

Twenty-four studies used at least one stand-alone measure of misuse, 46 studies used at least one composite measure of misuse and 20 studies used both types of measures. Of the 46 studies that used a composite measure, only five reported the proportion of the cohort exhibiting each component of a composite measure [31–35]. The other studies did not detail the relative contribution of each component to the extent of misuse.

3.5 The Extent of Prescription Drug Misuse (ESM 8)

The extent of misuse ranged from 0.01 to 93.5 %, and was generally higher for stand-alone measures compared with composite measures (for the latter, individuals needed to exhibit at least two characteristics or behaviors, as opposed to one). The variability in the extent of misuse reported across the studies reflected the heterogeneity in methodology; more specifically, measures and thresholds of misuse, cohort definitions and the time period of assessment.

3.5.1 Measures and Thresholds of Misuse

Overall, 89 unique definitions of misuse were identified across 50 studies; only 13 measures were utilized in two or more studies (32 studies in total). There appeared to be an attempt to use pre-existing measure(s) of misuse within, but not between, research groups; however, some groups changed their misuse measures between studies.

Sixteen studies reported the number of prescribers and/or dispensing pharmacies accessed routinely by drug-users. As thresholds increased, the proportion of the population exhibiting the behavior decreased (Fig. 2a, b). Importantly, the highest proportion of drug-users visited 1–2 prescribers or pharmacies when accessing their drug(s). Thirteen of these studies defined a threshold of misuse; nine studies (69.2 %) set the threshold of misuse as ≥3 prescribers or dispensing pharmacies. The thresholds defining misuse impacts on the extent of the problem reported across studies.

3.5.2 Cohort Definition (Drug-User and Misuse Cohorts)

Misuse was measured more frequently in drug-user cohorts (87 instances) than misuse cohorts (33 instances). The extent of misuse was most commonly <10 % for drug-users (58 instances, 66.7 %) and >20 % in misuse cohorts (23 instances, 69.7 %). However, the extent of misuse ranged considerably between drug-user (0.01–63.2 %) and misuse (0.2–93.5 %) cohorts, reflecting the variation in the measures and thresholds utilized, and the cohort definition. A strict cohort definition increased the reported extent of misuse; misuse cohorts had stricter cohort definitions than drug-user cohorts. In general, for drug-user cohorts a high reported extent of misuse reflected a low threshold for misuse, and for misuse cohorts the higher the reported extent of misuse, the stricter the cohort definition.

3.5.3 Time Period of Assessment

Measures of misuse were assessed from 7 days to 4 years. The most commonly investigated time period was 12 months, utilized in 44 % of instances of reporting misuse. Due to the heterogeneity of thresholds of misuse and cohort definitions, we were unable to make any further observations concerning the time period of assessment.

3.6 Factors Associated with Prescription Drug Misuse (ESM 9)

Fifteen studies investigated variations in the extent of misuse based on drug class (four studies), specific drug[s] (12 studies) and/or formulation(s) of interest (three studies).

Four studies compared the extent of misuse across different drug classes based on the same measure of misuse within each study and found opioid misuse was higher than benzodiazepine misuse (no statistical comparisons were performed) [36–39].

Six studies compared the extent of misuse for two or more drugs in the same class. In the opioid class, oxycodone (compared with tapentadol) and methadone (compared with morphine, oxycodone, fentanyl and hydrocodone) had a significantly higher risk of misuse-related behavior [40, 41]. Within the benzodiazepine class, three studies demonstrated that flunitrazepam had the highest extent of misuse compared with several other benzodiazepines [42, 43]. Within the antidepressant class, tianeptine (compared with mianserin) had the highest extent of misuse [44]. However, no statistical comparisons were performed in the benzodiazepine or antidepressant studies.

Three studies explored the influence of the drug formulation on the extent of misuse. A larger proportion of stronger benzodiazepines [42] and short-acting opioids [45] were dispensed to the misuse cohort compared with weaker or long-acting counterparts, respectively.

3.7 Justification of Measures of Misuse

Thirty-four studies reported a basic rationale for at least one measure of misuse by either citing previously published work (24 studies), mostly their own; using recommendations of an expert panel (six studies); and/or via empirical analysis (14 studies). Ten studies utilized more than one method of justification. Eighteen studies (34.6 %) did not report a rationale for their choice of measure of misuse.

3.8 Comprehensiveness of Reporting Observational Studies

The median STROBE score was 27 (range 19–33; IQR 23–29) out of a possible 36. Many studies did not report basic cohort details, including sex (20), age (18) and/or cohort size (8). Studies did not identify how they managed any bias (26), loss to follow up (39), missing data (39) or sensitivity analyses (38). Furthermore, 21 studies did not report the funding source.

Forty studies were published from 2008, after the STROBE statement was published; the median STROBE score was 25.5 (range 19–31; IQR 22–30) for studies published prior to the STROBE statement, and 27 (range 19–33; IQR 24–29) for studies published post the STROBE publication.

4 Discussion

Our systematic review synthesized the global literature quantifying prescription drug misuse based on population-level, routinely collected data. Our aim was to examine the measures, extent and factors associated with prescription drug misuse. We found a high level of consistency in the behaviors measuring misuse across the 52 studies, reflecting common jurisdictional data holdings and the limited number of variables with the capacity to investigate misuse behavior in routine data collections. However, due to the heterogeneity in thresholds of misuse, cohort definitions and time period of assessment, we were unable to make definitive comparisons regarding the extent or factors associated with misuse across time or healthcare settings. Despite this significant limitation in the current literature, going forward, the international research community has the capacity to make significant and timely inroads in this field by developing and harmonizing minimum reporting standards for a core set of pre-defined metrics. Our review and recommendations are timely and highly pertinent to the recent FDA call for submissions regarding the post-market surveillance of specific prescription opioids [24].

The harms associated with prescription drug misuse, particularly opioid misuse, have now reached epidemic proportions in many jurisdictions internationally [46, 47]. Despite the escalation in prescription drug use and consequences of misuse [8, 48, 49], we have limited knowledge about the extent of, and variations in, population-level misuse globally. We propose that a comprehensive and harmonized evidence-base, underpinned by routinely collected data, monitoring the extent of prescription drug misuse, will add significant value to the global effort in quantifying this problem. Moreover, this effort will enhance our understanding of the impact of policy responses attempting to address this problem.

The use of dispensing claims for post-market drug surveillance is a cost effective means of monitoring longitudinal, population-level prescription drug use and misuse. Many regulatory and funding agencies use dispensing claims to monitor prescription drug use, misuse and/or diversion [23]. In this review, we demonstrate routine dispensing data are used increasingly in peer-reviewed literature to explore prescription drug misuse, with over 60 % of reviewed studies published since 2010. Findings from population-level, routinely collected dispensing/prescription data have the capacity to complement other methodological approaches, such as detailed medical record reviews, surveys and in-depth qualitative studies, to enhance our understanding of prescription drug misuse. Moreover, linking dispensing claims with other routinely collected health data, such as hospitalizations and vital status will also provide further insight into the risk factors and drug access patterns related to harm.

Our review has several limitations. It is not certain that all relevant studies were captured. Over 10,000 abstracts were reviewed and a comprehensive search strategy was employed to identify relevant articles [50]; 14 studies were identified through back references, Scopus citations or Google Scholar searches, indicating the challenges of targeted searching and the diversity of keywords and subject headings used across studies. Articles that were not published in English were excluded; as nearly half of the included studies originated from Europe, we may have missed studies published in other languages [51, 52]. Our estimates of prescription drug misuse are solely from the perspective of the healthcare payer; we are unable to address access issues outside the dispensing episodes observed in the data including medication obtained illegally. The STROBE guidelines were applied to all studies, irrespective of publication date. However, the results did not vary considerably for studies published prior to or post STROBE statement publication. A search of journal contents was not undertaken due to the diversity of journals where the studies were published (32 different journals for 52 studies) [52]. These limitations do not impact our key findings. In fact, adding more studies is likely to contribute further to the heterogeneity we found across the field. Studies and metrics were categorized to synthesize the disparate literature. For example, misuse measures were categorized as stand-alone or composite measures. All measures based on a single behavior (e.g. ≥4 prescribers in 6 months) applied to a previously identified misuse cohort (e.g. ≥4 dispensing pharmacies in 6 months) were categorized as composite measures. These occurrences could have been categorized as stand-alone measures; however, this choice impacts on data presentation, not key findings. Finally, a key limitation of the literature is the notable absence of validation to establish whether the proxies actually measure misuse or are associated with harm [23].

Despite these limitations, this is one of the most comprehensive systematic reviews of this field to date. Our review was highly focused on measuring prescription drug misuse in routinely collected data. Other published reviews focused on jurisdiction-specific literature [23, 47, 53–56], self-report or medical chart data to ascertain use [47, 55–57], specific drug classes [23, 53, 54, 57] or patient populations [54–57]. The interpretation of these reviews were also impeded by the heterogeneity in study design [54, 56] and/or methods [47, 54–56]. However, the authors of these reviews did not suggest any practical solutions for unifying research in the field. Our recommendations provide a foundation that will increase the dialogue between researchers and unify future routine monitoring and post-market surveillance research (see Sect. 4.1). Our study complements two recent comprehensive reviews; one examining the patient, prescriber and environmental characteristics associated with opioid-related death [54], and the other an overview by FDA researchers of the appropriateness of US data sources for measuring prescription opioid abuse [23].

4.1 Reporting Recommendations

We have developed recommendations to harmonize the measurement and reporting of prescription drug misuse in routine data collections. These recommendations were not part of the original study objectives; instead they are underpinned by the learning in this review, particularly the challenges we faced in identifying studies and comparing the extent of misuse across studies (Box 2). Our recommendations center around three key areas: methodology (promotion of consistent metrics to determine appropriate measures of misuse), reporting (listing all drugs by generic name included in each study and the specifics of the misuse measures) and study nomenclature (where possible, consistency in the use of keywords including ‘prescription drug misuse’, that facilitate direct mapping to searchable subject headings). Future studies should combine these recommendations with the current standard reporting requirements for observational studies [26, 27], which will support the current FDA initiative and add value across other jurisdictions.

6 Conclusions

Prescription drug misuse has reached epidemic proportions in the US and is fast increasing in other jurisdictions. Despite the consistency in data holdings and behaviors used to define misuse in routine data collections we found considerable variation in measures of prescription drug misuse, cohort definitions and time periods of assessment. The adoption and modification of policies targeting prescription drug misuse are easier to argue for (or against) when the impacts are measured robustly and reproducible effects have been demonstrated across multiple settings. Thus, having consistent metrics for prescription drug misuse across jurisdictions is a very simple step, but one with potentially far-reaching consequences.

References

Barrett SP, Meisner JR, Stewart SH. What constitutes prescription drug misuse? Problems and pitfalls of current conceptualizations. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2008;1(3):255–62.

Nolan W, Gannon R. Combating the increase in opioid misuse. Conn Med. 2013;77(8):495–8.

Bartley J, Watkins LR. Comment on: excessive opioid use and the development of chronic migraine. Pain. 2009;145(1–2):262–3.

Baandrup L, Allerup P, Lublin H, Nordentoft M, Peacock L, Glenthoj B. Evaluation of a multifaceted intervention to limit excessive antipsychotic co-prescribing in schizophrenia out-patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122(5):367–74.

Petersen AB, Andersen SE, Christensen M, Larsen HL. Adverse effects associated with high-dose olanzapine therapy in patients admitted to inpatient psychiatric care. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52(1):39–43.

Huston B, Mills K, Froloff V, McGee M. Bladder rupture after intentional medication overdose. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2012;33(2):184–5.

Garland EL, Froeliger B, Zeidan F, Partin K, Howard MO. The downward spiral of chronic pain, prescription opioid misuse, and addiction: cognitive, affective, and neuropsychopharmacologic pathways. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(10 Pt 2):2597–607.

Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Dhalla IA, Paterson J, Juurlink DN. Opioid dose and drug-related mortality in patients with nonmalignant pain. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(7):686–91.

Paulozzi LJ, Kilbourne EM, Shah NG, et al. A history of being prescribed controlled substances and risk of drug overdose death. Pain Med. 2012;13(1):87–95.

Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study [summary for patients in Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):I-42]. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):85–92.

Paulozzi LJ. Prescription drug overdoses: a review. J Saf Res. 2012;43(4):283–9.

Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309(7):657–9.

Hall AJ, Logan JE, Toblin RL, et al. Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA. 2008;300(22):2613–20.

Jones JD, Mogali S, Comer SD. Polydrug abuse: a review of opioid and benzodiazepine combination use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125(1–2):8–18.

Gudin JA, Mogali S, Jones JD, Comer SD. Risks, management, and monitoring of combination opioid, benzodiazepines, and/or alcohol use. Postgrad Med. 2013;125(4):115–30.

Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I, et al. Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(1):38–47.

Braker LS, Reese AE, Card RO, Van Howe RS. Screening for potential prescription opioid misuse in a Michigan Medicaid population. Fam Med. 2009;41(10):729–34.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. NSDUH series H-46, HHS publication no. (SMA) 13-4795, 2013. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2012SummNatFindDetTables/NationalFindings/NSDUHresults2012.htm#ch2. Accessed 1 May 2015.

Merlo LJ, Singhakant S, Cummings SM, Cottler LB. Reasons for misuse of prescription medication among physicians undergoing monitoring by a physician health program. J Addict Med. 2013;7(5):349–53.

Fulton HG, Barrett SP, Stewart SH, MacIsaac C. Prescription opioid misuse: characteristics of earliest and most recent memory of hydromorphone use. J Addict Med. 2012;6(2):137–44.

McCall KL III, Tu C, Lacroix M, Holt C, Wallace KL, Balk J. Controlled substance prescribing trends and physician and pharmacy utilization patterns: epidemiological analysis of the Maine prescription monitoring program from 2006 to 2010. J Subst Use. 2013;18(6):467–75.

Hernandez SH, Nelson LS. Prescription drug abuse: insight into the epidemic. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88(3):307–17.

Secora AM, Dormitzer CM, Staffa JA, Dal Pan GJ. Measures to quantify the abuse of prescription opioids: a review of data sources and metrics. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(12):1227–37.

US Department of Health & Human Services. Postmarketing requirements for the class-wide extended-release/long-acting opioid analgesics. 2014. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/newsevents/ucm384489.htm. Accessed 30 Jun 2014.

Carnahan RM, Moores KG. Mini-Sentinel’s systematic reviews of validated methods for identifying health outcomes using administrative and claims data: methods and lessons learned. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(Suppl 1):82–9.

von Elm EMD, Altman DGD, Egger MMD, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573–7.

Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiol. 2007;18(6):805–35.

Zacny J, Bigelow G, Compton P, Foley K, Iguchi M, Sannerud C. College on Problems of Drug Dependence taskforce on prescription opioid non-medical use and abuse: position statement. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;69(3):215–32.

Larance B, Degenhardt L, Lintzeris N, Winstock A, Mattick R. Definitions related to the use of pharmaceutical opioids: extramedical use, diversion, non-adherence and aberrant medication-related behaviours. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2011;30(3):236–45.

Smith SM, Dart RC, Katz NP, et al. Classification and definition of misuse, abuse, and related events in clinical trials: ACTTION systematic review and recommendations. Pain. 2013;154(11):2287–96.

Katz N, Panas L, Kim M, et al. Usefulness of prescription monitoring programs for surveillance: analysis of Schedule II opioid prescription data in Massachusetts, 1996–2006. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(2):115–23.

Logan J, Liu Y, Paulozzi L, Zhang K, Jones C. Opioid prescribing in emergency departments: the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing and misuse. Med Care. 2013;51(8):646–53.

Pearson S-A, Soumerai S, Mah C, et al. Racial disparities in access after regulatory surveillance of benzodiazepines. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(5):572–9.

Peirce GL, Smith MJ, Abate MA, Halverson J. Doctor and pharmacy shopping for controlled substances. Med Care. 2012;50(6):494–500.

Bachs LC, Bramness JG, Engeland A, Skurtveit S. Repeated dispensing of codeine is associated with high consumption of benzodiazepines. Nor Epidemiol. 2008;18(2):185–90.

Cepeda MS, Fife D, Chow W, Mastrogiovanni G, Henderson SC. Assessing opioid shopping behaviour: a large cohort study from a medication dispensing database in the US. Drug Saf. 2012;35(4):325–34.

Dormuth CR, Miller TA, Huang A, et al. Effect of a centralized prescription network on inappropriate prescriptions for opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines. CMAJ. 2012;184(16):E852–6.

Wilsey BL, Fishman SM, Gilson AM, et al. Profiling multiple provider prescribing of opioids, benzodiazepines, stimulants, and anorectics. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112(1–2):99–106.

Pauly V, Pradel V, Pourcel L, et al. Estimated magnitude of diversion and abuse of opioids relative to benzodiazepines in France. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;126(1–2):13–20.

Cepeda MS, Fife D, Vo L, Mastrogiovanni G, Yuan Y. Comparison of opioid doctor shopping for tapentadol and oxycodone: a cohort study. J Pain. 2013;14(2):158–64.

Wilsey BL, Fishman SM, Gilson AM, et al. An analysis of the number of multiple prescribers for opioids utilizing data from the California Prescription Monitoring Program. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(12):1262–8.

Pradel V, Delga C, Rouby F, Micallef J, Lapeyre-Mestre M. Assessment of abuse potential of benzodiazepines from a prescription database using ‘doctor shopping’ as an indicator. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(7):611–20.

Pauly V, Frauger E, Pradel V, et al. Monitoring of benzodiazepine diversion using a multi-indicator approach. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;26(5):268–77.

Rouby F, Pradel V, Frauger E, et al. Assessment of abuse of tianeptine from a reimbursement database using ‘doctor-shopping’ as an indicator. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2012;26(2):286–94.

Gilson AM, Fishman SM, Wilsey BL, Casamalhuapa C, Baxi H. Time series analysis of California’s prescription monitoring program: impact on prescribing and multiple provider episodes. J Pain. 2012;13(2):103–11.

McCarthy M. Prescription drug abuse up sharply in the USA. Lancet. 2007;369(9572):1505–6.

Casati A, Sedefov R, Pfeiffer-Gerschel T. Misuse of medicines in the European Union: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Addict Res. 2012;18(5):228–45.

Blanch B, Pearson S, Haber PS. An overview of the patterns of prescription opioid use, costs and related harms in Australia. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(5):1159–66.

Unick GJ, Rosenblum D, Mars S, Ciccarone D. Intertwined epidemics: national demographic trends in hospitalizations for heroin- and opioid-related overdoses, 1993–2009. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e54496.

Hoffmann T, Erueti C, Thorning S, Glasziou P. The scatter of research: cross sectional comparison of randomised trials and systematic reviews across specialties. BMJ. 2012;344:e3223.

Martin-Latry K, Begaud B. Pharmacoepidemiological research using French reimbursement databases: yes we can! Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(3):256–65.

Glasziou P. Systematic reviews in health care: a practical guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

Fischer B, Argento E. Prescription opioid related misuse, harms, diversion and interventions in Canada: a review. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3 Suppl):ES191–203.

King NB, Fraser V, Boikos C, Richardson R, Harper S. Determinants of increased opioid-related mortality in the United States and Canada, 1990–2013: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(8):e32–42.

Turk DC, Swanson KS, Gatchel RJ. Predicting opioid misuse by chronic pain patients: a systematic review and literature synthesis. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(6):497–508.

Young AM, Glover N, Havens JR. Nonmedical use of prescription medications among adolescents in the United States: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(1):6–17.

Wilens TE, Adler LA, Adams J, et al. Misuse and diversion of stimulants prescribed for ADHD: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(1):21–31.

Bellanger L, Vigneau C, Pivette J, Jolliet P, Sébille V. Discrimination of psychotropic drugs over-consumers using a threshold exceedance based approach. Stat Anal Data Min. 2013;6(2):91–101.

Bramness JG, Furu K, Engeland A, Skurtveit S. Carisoprodol use and abuse in Norway: a pharmacoepidemiological study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64(2):210–8.

Gjerden P, Bramness JG, Slørdal L. The use and potential abuse of anticholinergic antiparkinson drugs in Norway: a pharmacoepidemiological study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67(2):228–33.

Wainstein L, Victorri-Vigneau C, Sebille V, et al. Pharmacoepidemiological characterization of psychotropic drugs consumption using a latent class analysis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;26(1):54–62.

White AG, Birnbaum HG, Schiller M, Tang J, Katz NP. Analytic models to identify patients at risk for prescription opioid abuse. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(12):897–906.

Parente ST, Kim SS, Finch MD, et al. Identifying controlled substance patterns of utilization requiring evaluation using administrative claims data. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11 Pt 1):783–90.

Victorri-Vigneau C, Feuillet F, Wainstein L, et al. Pharmacoepidemiological characterisation of zolpidem and zopiclone usage. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(11):1965–72.

Cepeda MS, Fife D, Berlin JA, Mastrogiovanni G, Yuan Y. Characteristics of prescribers whose patients shop for opioids: results from a cohort study. J Opioid Manag. 2012;8(5):285–91.

Martin BC, Fan M-Y, Edlund MJ, Devries A, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Long-term chronic opioid therapy discontinuation rates from the TROUP study. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1450–7.

Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Fan M-Y, Devries A, Brennan Braden J, Martin BC. Risks for possible and probable opioid misuse among recipients of chronic opioid therapy in commercial and medicaid insurance plans: The TROUP Study. Pain. 2010;150(2):332–9.

Nordmann S, Pradel V, Lapeyre-Mestre M, et al. Doctor shopping reveals geographical variations in opioid abuse. Pain Physician. 2013;16(1):89–100.

Pauly V, Frauger E, Pradel V, et al. Which indicators can public health authorities use to monitor prescription drug abuse and evaluate the impact of regulatory measures? Controlling high dosage buprenorphine abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113(1):29–36.

Pradel V, Frauger E, Thirion X, et al. Impact of a prescription monitoring program on doctor-shopping for high dosage buprenorphine. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(1):36–43.

Pradel V, Thirion X, Ronfle E, Masut A, Micallef J, Begaud B. Assessment of doctor-shopping for high dosage buprenorphine maintenance treatment in a French region: development of a new method for prescription database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13(7):473–81.

Cepeda MS, Fife D, Chow W, Mastrogiovanni G, Henderson SC. Opioid shopping behavior: how often, how soon, which drugs, and what payment method. J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;53(1):112–7.

Frauger E, Pauly V, Thirion X, et al. Estimation of clonazepam abuse liability: a new method using a reimbursed drug database. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;24(6):318–24.

Frauger E, Pauly V, Natali F, et al. Patterns of methylphenidate use and assessment of its abuse and diversion in two French administrative areas using a proxy of deviant behaviour determined from a reimbursement database: main trends from 2005 to 2008. CNS Drugs. 2011;25(5):415–24.

Cepeda MS, Fife D, Yuan Y, Mastrogiovanni G. Distance traveled and frequency of interstate opioid dispensing in opioid shoppers and nonshoppers. J Pain. 2013;14(10):1158–61.

Hoffman L, Enders JL, Pippins J, Segal R. Reducing claims for prescription drugs with a high potential for abuse. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003;60(4):371–4.

Skurtveit S, Furu K, Borchgrevink P, Handal M, Fredheim O. To what extent does a cohort of new users of weak opioids develop persistent or probable problematic opioid use? Pain. 2011;152(7):1555–61.

Thirion X, Lapierre V, Micallef J, et al. Buprenorphine prescription by general practitioners in a French region. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;65(2):197–204.

Goodman FDC, Glassman P. Evaluating potentially aberrant outpatient prescriptions for extended-release oxycodone. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62(24):2604–8.

Mailloux AT, Cummings SW, Mugdh M. A decision support tool for identifying abuse of controlled substances by ForwardHealth Medicaid members. J Hosp Mark Public Relations. 2010;20(1):34–55.

Ross-Degnan D, Simoni-Wastila L, Brown JS, et al. A controlled study of the effects of state surveillance on indicators of problematic and non-problematic benzodiazepine use in a Medicaid population. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2004;34(2):103–23.

Victorri-Vigneau C, Sebille V, Gerardin M, Simon D, Pivette J, Jolliet P. Epidemiological characterization of drug overconsumption: the example of antidepressants. J Addict Dis. 2011;30(4):342–50.

Soumerai SB, Simoni-Wastila L, Singer C, et al. Lack of relationship between long-term use of benzodiazepines and escalation to high dosages. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(7):1006–11.

Simoni-Wastila L, Ross-Degnan D, Mah C, et al. A retrospective data analysis of the impact of the New York triplicate prescription program on benzodiazepine use in Medicaid patients with chronic psychiatric and neurologic disorders. Clin Ther. 2004;26(2):322–36.

Bramness JG, Rossow I. Can the total consumption of a medicinal drug be used as an indicator of excessive use? The case of carisoprodol. Drugs Edu Prev Policy. 2010;17(2):168–80.

Fredheim OMS, Skurtveit S, Moroz A, Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC. Prescription pattern of codeine for non-malignant pain: a pharmacoepidemiological study from the Norwegian Prescription Database. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53(5):627–33.

Hartz I, Tverdal A, Skurtveit S. Social inequalities in use of potentially addictive drugs in Norway: use among disability pensioners. Nor Epidemiol. 2009;19(2):209–18.

Victorri-Vigneau C, Basset G, Jolliet P. How a novel programme for increasing awareness of health professionals resulted in a 14 % decrease in patients using excessive doses of psychotropic drugs in western France. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62(4):311–6.

Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan [published erratum appears in JAMA. 2012;307(23):2489]. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940–7.

Rice JB, White AG, Birnbaum HG, Schiller M, Brown DA, Roland CL. A model to identify patients at risk for prescription opioid abuse, dependence, and misuse. Pain Med. 2012;13(9):1162–73.

McDonald DC, Carlson KE. Estimating the prevalence of opioid diversion by “doctor shoppers” in the United States. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69241.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Matthew Davis for assistance in refining the search strategies and for technical support.

Funding/support

This research has been supported, in part, by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre of Research Excellence in Medicines (APP1060407). Bianca Blanch is supported by a University of Sydney Postgraduate Award (2013–2016); Sallie-Anne Pearson is supported by a Cancer Institute New South Wales Career Development Fellowship (ID: 12/CDF/2-25); Nicholas Buckley and Andrew Dawson receive support for toxicovigilance studies through an NHMRC Program Grant (1055176); and Andrew Dawson is also supported by an NHRMC practitioner fellowship (1059542).

Conflict of interest

Bianca Blanch, Nicholas Buckley, Leigh Mellish, Andrew Dawson, Paul Haber and Sallie-Anne Pearson have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blanch, B., Buckley, N.A., Mellish, L. et al. Harmonizing Post-Market Surveillance of Prescription Drug Misuse: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies Using Routinely Collected Data (2000–2013). Drug Saf 38, 553–564 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-015-0294-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-015-0294-8