Abstract

Background

Acne (syn: acne vulgaris) ranks as the most common inflammatory dermatosis treated worldwide. Acne typically affects adolescents at a time when they are undergoing maximum physical and social transitions, although prevalence studies suggest it is starting earlier and lasting longer, particularly in female patients. According to global burden of disease studies, acne causes significant psychosocial impact. Hence, identifying mechanisms to accurately measure the impact of the disease is important. Adopting an approach to harmonize and standardize measurements is now recognized as an essential part of any clinical evaluation and allows for better comparison across studies and meta-analyses.

Objective

The Acne Core Outcome Research Network (ACORN) has identified relevant domains as part of a core outcome set of measures for use in clinical studies. One of these is health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The aim of this systematic review was to provide information to inform the identification of the impacts most important to people with acne.

Methods

A synthesis of available evidence on acne impacts was constructed from a systematic review of the literature, with searches conducted in the MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsychInfo databases.

Results

We identified 408 studies from 58 countries using 138 different instruments to detect the impacts of acne. Four of the five most commonly used instruments (Dermatology Life Quality Index [DLQI], Cardiff Acne Disability Index [CADI], Acne Quality of Life scale [Acne-QoL], Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS] and Skindex-29) do not identify specific impacts but rather quantify to what extent acne affects HRQoL. Other studies identified one or more impacts using open-ended questions or tailor-made questionnaires.

Conclusion

This review serves as a rich data source for future efforts by groups such as ACORN (that include patients and health care providers) to develop a core set of outcome measurements for use in clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There is a paucity of methodologically rigorous studies assessing the impact of acne. |

A wide range of instruments have been used to detect and measure impacts. |

Only 3 of the 10 most commonly used measures were not quality-of-life questionnaires. |

The most frequently studied specific impacts were reduced wellness; negative emotions, including depression and anxiety; and negative self-perception, including concerns regarding appearance and self-image. |

The frequency of the impacts reported reflects the bias introduced by the investigator’s selection of the instruments used to assess the impact of acne rather than the impacts deemed most important by patients themselves. |

Only 22 of 408 papers adopted a qualitative approach focusing on what was important to people with acne. |

Measurement of health-related quality of life in acne trials requires rigorous re-evaluation, standardization and validation before inclusion in a core outcome set for universal adoption. The central role of appearance-related concerns is a key area for consideration, and, based on this review, has been underestimated. |

1 Introduction

The Acne Core Outcome Research Network (ACORN) was established in 2013 to identify core outcome sets for use in clinical studies of acne and its treatment. The intention is that these core outcomes will be internationally relevant, widely adopted and consequently be measured and reported in all future clinical trials of acne therapies. The core outcome set has recently been agreed upon via international consensus between stakeholders, and includes health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [1]. The question thus arises as to which aspects of acne-related QoL (ARQoL) matter most to patients and how best to measure these. Whilet Barnes et al. [2] reviewed a number of dermatology and disease-specific instruments that had been used to assess the effects of acne on HRQoL, their goals were to identify the best available instruments for routine clinical use and the factors responsible for low HRQoL. They did not determine whether any existing instrument is fit-for-purpose in that it reproducibly measures the most important impacts as identified by people with acne and is able to detect meaningful change within clinical trials or in everyday clinical practice. Alexis et al. [3] elected to devise a new patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) for acne that is based on a critical appraisal of four existing acne-specific HRQoL questionnaires [4,5,6,7]. This appraisal identified that none of the questionnaires fulfilled the criteria set out in the US FDA Guidance for Industry on the development and evaluation of PROMs [8]. A recent systematic review of instruments used to assess HRQoL in acne based its recommendations for future use on the frequency of adoption of the tools, not fitness-for-purpose or critical appraisal by patients and/or healthcare professionals [9].

The primary aim of this systematic review is to identify and characterize all studies, irrespective of methodology or setting, which have sought to capture the impact of acne vulgaris on people’s lives. From these we will generate a collated list of acne impacts and a conceptual framework to inform further stages in the identification of the impacts most important to patients. A secondary objective is to examine use of instruments, not limited to HRQoL questionnaires, which have been employed to identify impacts.

In a future stage, we will examine how strongly the identified impacts are associated with acne and how well they correlate with acne severity. The results from this future analysis will be reported separately.

Data will be used to generate an evidence-based shortlist of items, which will inform the selection or development of the core outcome measure used to assess ARQoL and/or other domains, such as satisfaction with appearance or long-term control of acne, in future acne trials.

2 Methods

2.1 Literature Searches

Search strategies were designed with the help of two librarians to locate studies that included acne patients of any age or ethnicity and addressed either HRQoL or specific impacts of skin disease, using any methodology (Online Appendix 1). A large range of impact-related search terms were utilized, leading to a large number of papers that required exclusion. The impacts sought included, but were not limited to, the effects on psychological wellbeing, social wellbeing, cognitive functioning, daily activities (including work, study and recreation) and personal constructs (self-concepts). We did not search for specific mental health or personality disorders as specified in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems version 10 (ICD-10), Chapter V, Mental and Behavioral Disorders. Studies were also excluded if they involved patients with other types of acne or in which acne vulgaris was part of a clinical condition such as polycystic ovarian syndrome. Reviews, commentaries or any other publication types that contained no original data, as well as studies published in abstract form only or not written in English, were also excluded. Searches were conducted in the MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsychInfo databases from inception to 31 December 2015. A full search of the grey literature was not included. The searches were updated on 1 November 2017 to include articles published in 2016. The search was further updated on 11 April 2020 to include articles published in 2017 and 2018.

After de-duplication in Endnote™, search outputs were exported in Rayyan (https://rayyan.qcri.org/) to facilitate sorting. Two of four reviewers (AE, DT, HS, HW) scanned titles and abstracts up to and including papers published in 2018 for articles meeting the inclusion criteria; any disagreements were resolved by discussion. Full texts of articles that met the inclusion criteria or upon which a decision could not be made without further information were retrieved. Articles about which there was uncertainty were only rejected after appraisal of the full text.

2.2 Data Extraction

2.2.1 Characteristics of the Included Studies

For each included study, we identified the country or countries of origin, date of publication, number of participants with acne, number of healthy controls and/or number of subjects with other diseases (if any) for comparison. Impact factors of the journals in which the articles had been published were obtained from InCites Journal Citation Reports (Clarivate Analytics). SCImago Journal Rank (SJR) indicators (referred to as rank indicators), which are more widely available than impact factors for lesser-known journals, were obtained from SCImago. These were used as surrogate markers for quality as the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) could not be used for comparison as study designs were so variable.

2.3 Use of Questionnaires

Included studies were appraised by two of six potential reviewers (AE, DT, AL, WG, HS, AS) to identify which questionnaires had been used by the authors to capture information on acne impacts. We recorded the total number of different instruments used and the number of times each different questionnaire had been used in any setting. We recorded separately use in randomized controlled trials, as appropriateness and responsiveness in this setting are key criteria for a core outcome measure. From the extracted data, we identified the most commonly used instruments and the impacts they addressed.

2.4 Identification of Impacts

To identify the different ways acne impacts on people’s lives, a theoretical thematic analysis of the included review papers (dataset) as described by Braun and Clarke [10] was undertaken in five key stages.

First, a process of immersion took place that involved repeated reading of the papers (AE). Next, we sought to generate the initial list of codes. To do this, data extraction and coding was undertaken to specifically identify the range of acne impacts reported across the papers as driven by the researchers (e.g. what impact of acne is being measured or explored in the papers?). Other aspects of the information included in the papers were therefore not included in the thematic analysis. For example, we did not extract data on any signs or symptoms of acne that may have been reported in the manuscripts.

Impacts of acne addressed by each study were extracted from each paper (data item) into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) by two reviewers (AE, HS) and checked by a further four reviewers (DT, AL, WG, AS). Any anomalies in data extraction were reconciled against the source documents and involved consultation with the wider team. From the quantitative papers, quality of life was extracted as generic health-related (GHRQoL), dermatology-related (DRQoL) or acne-related (ARQoL) according to which questionnaire(s) had been used. For multi-domain instruments, impact information was extracted from the individual domains if relevant, specific and legitimate. Efforts were made to obtain as many as possible of the original questionnaires so that the meaning of ambiguous terms could be correctly interpreted. From the qualitative papers, the themes already generated by the authors were extracted but supporting quotes and text were reviewed to aid interpretation of the impacts identified.

During data extraction, each potentially distinct (different) impact was added to a list, so that at the end of this stage, a long list of codes had been identified from the dataset. The long list of codes was reduced once by pooling related items, discussed between a multidisciplinary team (dermatologists, psychologists, researcher and patient) and then reduced again. To pool the codes, extracted data that related to the same or very similar feelings (emotions or moods), perceptions or behaviors were pooled, while any items that may have been reported only once and appeared distinct were kept separate. This process started to organize the list into meaningful groups that described the content in the dataset. Extensive checking back with the original articles was conducted during this phase.

Following this process, the researchers then actively searched for themes among the coded data. The aim was to identify the semantic themes that described the coded descriptions of the acne impacts more broadly. This process was also iterative, where the themes actively identified by the researchers continued to be reviewed and refined. Finally, the themes were named, with the input of a psychologist, to ensure they were internally coherent, consistent with the source data, and, as far as possible, non-overlapping.

3 Results

3.1 Search Results

The search generated 4942 papers after deduplication. The majority of these were excluded at the abstract scanning phase as they were unrelated to acne impacts or did not meet the inclusion criteria (acne syndromes, review papers, etc.). Overall, 466 articles that potentially included information on acne impacts were identified. Of these, 55 were excluded after retrieving the full text (Fig. 1). Lists of the included and excluded studies are shown in Online Appendix 2. The 408 included articles did not represent 408 independent studies, as there were 24 instances in which data from the same cohort of patients had been included in two or more separate publications (electronic supplementary Table 1). These studies were retained as they were not identical, although some analyses were occasionally reported in more than one publication. Where this occurred, we extracted the duplicated information only once.

3.2 Study Characteristics

Key characteristics of the 408 included studies are shown in Table 1. These characteristics were published in 174 different journals, with the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology being the most popular (27 articles.) Journal impact factors were available for 308 articles (75.5%); 78 articles (19.1%) were published in journals with impact factors of ≥ 4, and 25 (6.1%) were published in journals with impact factors of < 1. Rank indicators were available for all but 36 articles (91.2%); 55.9% (228/408) had rank indicators of < 1.0 and only 48 (11.8%) had indicators of > 2.0.

Studies were conducted in 58 different countries, with three countries (USA = 84, UK = 38, and Turkey = 38) contributing 39.2% of the total. The number of participants with acne varied widely, from fewer than 10 to more than 10,000 (Table 1). Fifty-nine studies (14.6%) included healthy subjects without acne and 122 studies (30.2%) also included patients with other diseases, most commonly, but not limited to, other skin diseases; these were not always used as comparators. Only 36 studies (8.3%) were published before December 1999 (Fig. 2).

Study design varied extensively and included, but was not limited to, descriptive studies (usually case series sometimes including skin diseases other than acne), case–control studies, cross-sectional studies (diagnosis of interest unknown at the start, either acne status or psychiatric morbidity), cohort (longitudinal) studies, randomized controlled trials, non-randomized comparative clinical studies and open-label clinical studies with no comparator. The design of some studies defied conventional classification. It was especially difficult to distinguish between cohort studies and open-label clinical trials (investigator-assigned intervention). Identifying the prevalence or severity of one or more acne impacts including quality-of-life impairment was a stated objective in only 204 studies (50%). The remaining studies investigated acne impacts or quality of life in relation to a wide range of clinical questions, among the most common of which were the efficacy of acne therapies, the effect of isotretinoin on mood, and the development, validation and/or comparison of PROMs.

Only a relatively small number of studies (80, 19.6%) compared the prevalence or severity of the impact(s) identified with a control group. Similarly, few studies (70, 17.15%) looked for an association between the severity of an impact and the severity of acne.

3.3 Use of Questionnaires and Other Techniques to Assess Acne Impacts

A total of 135 different published instruments had been used to detect or measure acne impacts; this includes the children’s version of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI), Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and the Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory. A summary of the instruments used in the 408 studies reviewed is listed in electronic supplementary Table 2. In addition, 39 studies used unpublished questionnaires of their own design, six of which were used alongside other published questionnaires. Twenty-nine studies used interviews, including the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) Axis I Disorder, and two used focus groups to elicit information on impacts. One used in-depth semi-structured interviews. Among the published instruments, all had undergone some degree of validation and many had undergone extensive validation. However, older instruments had not always been validated in ways that would be regarded as rigorous by today’s standards. In consequence, we did not distinguish between validated and non-validated questionnaires. Additionally, three studies interrogated databases. While these demonstrated an association between acne and psychological impacts, they could not confirm a causal relationship between acne and the impact.

The most commonly used questionnaire was the Dermatology Quality of Life Index (DLQI), which was used in 83 studies (Table 2) [11]; the children’s version was used in 18 studies [12]. Of the top 10 instruments, only three did not evaluate HRQoL and instead had been used to measure other psychological constructs: the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HADS; n = 32), the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (n = 21) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; n = 21) [13,14,15]. The most frequently used acne-specific quality-of-life instrument was the full version of the Acne Quality of Life Scale (Acne-QoL; n = 35) [16]; however, a Skindex instrument (version 16, 17, 29, 61, or Teen version) [17,18,19,20,21] was used in 50 studies. The most commonly used generic HRQoL questionnaire was the Short-Form 36 (SF-36) [22]. Thirty-one of the 135 published questionnaires were available for use without permissions or payments, with 213 (52%) studies using one of these questionnaires. Additionally, the DLQI is widely available for use clinically but payment is required for commercially sponsored clinical trials. It is unclear how many of the 83 studies gained permission before utilizing the DLQI.

3.4 Use of Questionnaires in Randomized Controlled Trials That Assessed Patients Before and After an Intervention

Among the included studies, there were 51 RCTs (in 53 publications), of which all but two included the use of one or more HRQoL questionnaires, most commonly the DLQI and/or CDLQI, which were used in 16 RCTs. The Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI) was included in 10 RCTs. The 19-item version of the Acne Quality of Life Questionnaire (Acne-QOL) was used in eight trials and the Skindex-29 was used in five trials. The Acne Quality of Life Scale (AQOL) was included in four trials and the Skindex-16 was included in three trials. One study [23] used data from two identical pooled RCTs that employed the Acne-QoL [24] to estimate the minimally important clinical difference, and another used the same trials to assess the responsiveness of this instrument. Other dermatology or acne-specific QoL questionnaires were each used once: Assessment of the Psychological and Social Effects of Acne (APSEA), the 4-item version of Acne-QOL, the Dermatology-Specific Quality of Life Instrument (DSQL) and the Dermatology Quality of Life Scales (DQOLS). Only three trials included generic HRQoL instruments—the SF-36, the 26-item version of World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF) or the Psychological General Wellbeing Index. One trial [25] used a non-validated tailor-made instrument to assess HRQoL, and another used two subscales of the SF-36. Two of four RCTs of oral isotretinoin focused exclusively on mental health outcomes (anxiety, depression and/or suicide risk) and did not assess generic, dermatology-specific or acne-specific HRQoL [26, 27]. The Profile of Mood States and the Satisfaction with Life scale were each included in one trial alongside a measure of HRQoL [28, 29].

3.5 Impacts Identified

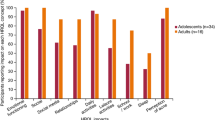

Overall, nine key themes that described the impact of acne were identified from the data (Table 3). These included but were not limited to (1) reduced wellness as assessed by QoL instruments (n = 260); (2) psychological consequences of acne (n = 172), including negative emotions such as anxiety (n = 85) and depression (n = 128); (3) negative self-perception (n = 92), including negative self-image (n = 57); and (4) negative effects on relationships (n = 91). The acne impacts identified within each theme are also shown in Table 3. A complete list of the codes identified prior to categorization is found in electronic supplementary Table 2.

Only 22 of 408 papers described the adoption of a qualitative approach that focused on what was the most important to people with acne. Of these, negative self-perception was the most commonly reported theme (n = 16), including negative self-image (n = 12), negative self-concept/belief (n = 12) and self-consciousness/self-conscious emotions (n = 7). Psychological consequences was another common theme (n = 15), followed by negative peer behaviors (n = 10), fear of negative evaluation (n = 10) and negative effects on relationships (n = 10).

Inconsistency in the terminology used across studies resulted in an unavoidable degree of ambiguity associated with our interpretation of the meaning of some terms.

For example, ‘depression’ was detected by self-report, computer read codes, 19 different validated scales, non-validated questionnaires, and unstructured, semi structured and structured interviews, including formal psychiatric interviews using DSM criteria.

4 Discussion

This review has identified numerous ways in which acne impacts patient’s lives. Many instruments have been used to assess these impacts, some of which are non-validated. There are currently no universally recognized instruments for use in acne patients that have been standardized in line with an agreed construct. There is also no standardization globally; for example, studies in Europe tend to assess HRQoL using the DLQI, whereas studies in the US tend to use Skindex.

Study designs varied significantly, many were not hypothesis-led and precluded application of the CONSORT criteria to assess quality. Journal impact factors and rank indicators were used as a surrogate to assess quality in this review. It is acknowledged that this is a limitation of the current study as this may not be fully reflective and less accurate than a mixed methods appraisal; however, this method does suggest studies were generally of poor quality.

Only 5% (22 of 408) were qualitative studies representing the patient perspective. Furthermore, there was a paucity of patient involvement in study design, and studies tended to assess multiple variables. As noted previously, the inconsistency in terminology used across studies resulted in an unavoidable degree of ambiguity when interpreting the meaning of some terms. For example, the variable ways of reporting depression was reflected in the results as a spectrum from low mood to major depressive disorder. Notably, negative self-perceptions appeared to be a recurring theme among the small number of qualitative studies.

Of the 408 papers identified in this review, the selection of tools was made by the investigator without taking the patient perspective into account. Over half of the tools were freely available to utilize without permission, including the CADI, which was the second most commonly utilized tool. The DLQI, the most commonly used tool, requires permission for use in commercially sponsored trials but is widely available for use clinically and is easy to access. Access to assessment tools may have influenced investigator choice and therefore could skew the interpretation of acne impacts. Investigators interviewed, or conducted focus groups with, patients to elicit the impacts of acne, and reported on what informed questionnaire development in only 22 (5.1%) studies. The item identification and reduction phases used to devise QoL questionnaires were rarely reported, possibly due to journal length restrictions. As such, pertinent and a potentially rich source of data have been lost.

In many cases, the frequency with which certain impacts are reported reflects the bias of the investigator in selecting which instruments to administer based on the purpose of the study. The choice of instrument is also likely influenced by the tendency for some of the same authors to repeatedly publish within this field. In examining the trends from 1941 to 2016, investigators in the very early studies chose to examine personality traits, self-perceptions and psychological consequences in acne patients. Subsequent development of instruments to measure quality of life related to general health, dermatologic disease or acne led to an increase in the number of studies examining QoL. These studies were designed to assess instrument measurement properties, assess QoL as an outcome of treatment, or compare QoL in acne patients with normal controls or people with other skin diseases. When concerns arose of a possible association of isotretinoin with depression, investigators conducted numerous studies to assess the effects of this drug on depression, anxiety and QoL. Many of these studies were significantly underpowered, therefore failing to produce robust or meaningful data. The surgence of these studies has most likely led to overrepresentation of depression and anxiety as impacts of acne in this review.

When considering qualitative data, discrepancies between patients and clinicians have been identified through an independent Delphi Survey, with concern regarding appearance emerging as a central theme [30]. Semi-structured interviews with 26 acne patients in a general practice also found concern regarding appearance to be a prominent impact [31]. Coded responses and themes from these semi-structured interviews were used to construct a schematic representation of interaction between acne and psychological disorders. Of interest, these authors noted that the symptoms of depression and anxiety were much less than would have been expected based on the quantitative literature.

Satisfaction with appearance was identified by 307 patients or their parents, and 218 health care providers in the ACORN group, as a core outcome domain that should be measured in all clinical trials [1]. This resonates with the previous community study [31] and more recent qualitative research in this area [32]. Compared with other domains, the greatest level of concordance between patients and providers was noted with regard to the voting on the inclusion of satisfaction with appearance as a core outcome domain to be measured in clinical trials.

5 Conclusions

This systematic review has generated a comprehensive list of the impacts of acne on patients and the frequency with which they were reported. This could lend itself to informing a future instrument to capture HRQoL and satisfaction with appearance through convergence of recognized impacts.

Figure 3 provides a conceptual framework to inform the next steps following on from this systematic review. It is important to note however that the frequency with which impacts were reported often relates to the choice of instrument made by the investigator rather than the importance of that impact to patients. This supports the recent Delphi process adopted to capture the impacts of acne [30] and the need for more qualitative research being conducted in this area. This review serves as a rich data source for future efforts by groups such as ACORN (that include patients and health care providers) to develop a core set of outcome measurements for use in clinical trials. The next steps are to identify which impacts reported correlate with the prevalence and/or severity of acne. This reduced list will be discussed further to identify a short list of impacts that are important to patients. Following methodologies outlined in the HOME roadmap [33], this shortened list can serve as a benchmark for the evaluation of existing instruments used to measure not only HRQoL but most likely additional core outcome domains such as ‘satisfaction with appearance’ and ‘long-term control of acne’.

References

Layton AM, Eady EA, Thiboutot DM, Tan J, the Acne Core Outcomes Research Network (ACORN) Outcomes Identification Group. Identifying what to measure in acne clinical trials: first steps towards development of a core outcome set. J Investig Dermatol. 2017;137(8):1784–6.

Barnes LE, Levender MM, Fleischer AB, Feldman SR. Quality of life measures for acne patients. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30(2):293–300.

Alexis A, Daniels SR, Johnson N, Pompilus F, Burgess SM, Harper JC. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for facial acne: the acne symptom and impact scale (ASIS). J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13(3):333–40.

Anderson R, Rajagopalan R. Responsiveness of the dermatology-specific quality of life (DSQL) instrument to treatment for acne vulgaris in a placebo-controlled clinical trial. Qual Life Res. 1998;7(8):723–34.

Girman CJ, Hartmaier S, Thiboutot D, et al. Evaluating health-related quality of life in patients with facial acne: development of a self-administered questionnaire for clinical trials. Qual Life Res. 1996;5(5):481–90.

Gupta MA, Johnson AM, Gupta AK. The development of an Acne Quality of Life scale: reliability, validity, and relation to subjective acne severity in mild to moderate acne vulgaris. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78(6):451–6.

Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Graham G, Fleischer AB, Brenes G, Dailey M. The Acne Quality of Life Index (Acne-QOLI): development and validation of a brief instrument. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7(3):185–92.

US Department of Health and Human Services, US FDA. Guidance for Industry. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. 2009.

Chernyshov PV, Zouboulis CC, Tomas-Aragones L, Jemec GB, Manolache L, Tzellos T, et al. Quality of life measurement in acne. Position paper of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Task Forces on quality of life and patient oriented outcomes and acne, rosacea and hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(2):194–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14585.

Braun V, Clark V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2008;3:2:77–101.

Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–21.

Lewis-Jones M, Finlay A. The Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI): initial validation and practical use. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:942–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb16953.x.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70.

Rosenberg M. Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books; 1979.

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71.

Girman CJ, Hartmaier S, Thiboutot D, et al. Evaluating health-related quality of life in patients with facial acne: development of a self-administered questionnaire for clinical trials. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:481–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00540020.

Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Sabek AP, Sands LP. Measurement properties of Skindex-16: a brief quality of life measure for patients with skin diseases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:105–10.

Nijsten TE, Sampogna F, Chren MM, Abeni DD. Testing and reducing Skindex-29 using Rasch analysis: Skindex-17. J Investig Dermatol. 2006;126:1244–50.

Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Flocke SA, Zyzanski SJ. Improved discriminative and evaluative capability of a refined version of Skindex, a quality-of-life instrument for patients with skin diseases. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1433–40.

Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Quinn LM, Mostow EN, Zyzanski SJ. Skindex, a quality of life measure for patients with skin disease: reliability, validity and responsiveness. J Investig Dermatol. 1996;107:707–13.

Smidt AC, Lai JS, Cella D, Patel S, Mancini AJ, Chamlin SL. Development and validation of Skindex-Teen, a quality-of-life instrument for adolescents with skin disease. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:865–9.

Ware JE, Sherboume CD. The MOS36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Mad Care. 1992;30:473–83.

McLeod LD, Fehnel SE, Brandman J, Symonds T. Evaluating minimal clinically important differences for the acne-specific quality of life questionnaire. Pharmacoeconomics. 2003;21:1069–79.

Maloney JM, Arbit DI, Flack M, McLaughlin-Miley C, Sevilla C. Use of a low-dose oral contraceptive containing norethindrone acetate and ethinyl estradiol in the treatment of moderate acne vulgaris. Clin J Womens Health. 2001;1:123–31.

Jung GW, Tse JE, Guiha I, Rao J. Prospective, randomized, open-label trial comparing the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of an acne treatment regimen with and without a probiotic supplement and minocycline in subjects with mild to moderate acne. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:114–22.

Strauss JS, Leyden JJ, Lucky AS, et al. Safety of a new micronized formulation of isotretinoin in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne: a randomized trial comparing micronized isotretinoin with standard isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:196–207.

Webster GF, Leyden JJ, Gross JA. Results of a phase III double-blind, randomised, parallel group non-inferiority study evaluating the safety and efficacy of isotretinoin-lidose in patients with severe, recalcitrant nodular acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:665–70.

Choi JM, Lew VK, Kimball AB. A single-blinded, randomized, controlled clinical trial evaluating the effect of face washing on acne vulgaris. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:421–7.

Winkler UH, Ferguson H, Mulders JA. Cycle control, quality of life and acne with two low-dose oral contraceptives containing 20 microg ethinylestradiol. Contraception. 2004;69:469–76.

Tan J, Frey MP, Thiboutot D, Layton A, Eady EA. Identifying the impacts of acne: a Delphi survey of patients and clinicians. J Cutan Med Surg. 2020;24(3):259–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1203475420907088.

Magin P, Adams J, Heading G, Pond D, Smith W. Psychological sequelae of acne vulgaris: results of a qualitative study. Can Fam Physician. 2006;52(8):978–9.

Kiassen A, Lipner S, O'Malley M, Longmire N, Cano S, Breitkopf T, et al. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure to evaluate treatments for acne and acne scarring: the ACNE-Q. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1207–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.18005.

Schmitt J, Apfelbacker C, Spuls PI, Thomas KS, Simpson EL, Furue M, et al. The harmonizing outcome measures for Eczema (HOME) roadmap: a methodological framework to develop core sets of outcome measurements in dermatology. J Investig Dermatol. 2015;135:24–30.

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene PR, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. San Jose: Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc.; 1983.

Derogitas RL, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13:595–605.

Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O'Connel KA, WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization's WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:299–310.

Motley RJ, Finlay AY. Practical use of a disability index in the routine management of acne. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:1–3.

Fenigstein A, Scheier MF, Buss AH. Public and private self-consciousness: assessment and theory. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1975;43:522–7.

Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50–5.

Hays RD, Morales LS. The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):350–7.

Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius N, Ustun TB, Piccinelli M, Gureje O, et al. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med. 1997;27:191–7.

Leibowitz MR. Social Phobia. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141–73.

Martin AR, Lookinbill DP, Botek A, Light J, Thiboutot D, Gitman CJ. Health-related quality of life among patients with facial acne: assessment of a new acne-specific questionnaire. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:380–5.

Motley RJ, Finlay AY. How much disability is caused by acne? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:194–8.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401.

McNair DM, Heuchert JP, Shilony E. Profile of mood states: bibliography 1964–2002. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems; 2003.

Layton AM, Seukeran D, Cunliffe WJ. Scarred for life? Dermatology. 1997;195(Suppl 1):15–211.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Helen Weir, HDFT Librarian, and Esther Dell, Penn State Librarian.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Alison Layton: Investigator and consultant for Galderma laboratories, Origimm, Proctor and Gamble, and La Roche Posay. Diane Thiboutot: Investigator and consultant for Galderma Laboratories, Biopharmix, and Cassiopea. Jerry Tan: Advisor, consultant, investigator and/or speaker for Allergan, Bausch, Botanix, Boots/Walgreens, Dermavant, Galderma, L’Oreal, and Novartis. Hayley Smith, Abbey Smith, Heather Whitehouse, Waseem Ghumra, Meenakshi Verma, Georgina Jones, Kathryn Gilliland, Megha Patel, Elaine Otchere, and Anne Eady have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding/Support

This work was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), award number 1U01AR065109-01.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Role of Funder/Sponsor

The NIH had no role in the design or conduct of this study, including data collection and analysis and preparation of this manuscript.

Availability of Data and Material

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this publication and the electronic supplementary files.

Code of Availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: Anne Eady, Alison Layton, Diane Thiboutot, Jerry Tan. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: Kathryn Gilliland, Anne Eady, Megha Patel, Elaine Otchere, Waseem Ghumra, Hayley Smith, Abbey Smith, Heather Whitehouse, Meenakshi Verma, Georgina Jones, Alison Layton, and Diane Thiboutot. Drafting of the manuscript: Anne Eady, Hayley Smith, Alison Layton. Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: Not applicable. Obtained funding: Diane Thiboutot. Administrative, technical or material support: Kathryn Gilliland. Study supervision: Diane Thiboutot and Alison Layton.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, H., Layton, A.M., Thiboutot, D. et al. Identifying the Impacts of Acne and the Use of Questionnaires to Detect These Impacts: A Systematic Literature Review. Am J Clin Dermatol 22, 159–171 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-020-00564-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-020-00564-6