Abstract

Purpose of Review

To synthesize findings regarding the psychological outcomes of face transplantation.

Recent Findings

Thirty-seven face transplants have been done since the world’s debutant case was featured in 2005. In spite of impressive clinical success, little has been achieved to date in terms of understanding the mental health, quality of life, and psychosocial outcomes of face transplant recipients.

Summary

We conducted a literature search in PubMed for studies reporting any psychosocial measure in face transplant recipients, between 2005 and 2017. We identified 20 articles: 11 articles reported qualitative evaluation of outcomes, and nine articles used quantitative measures. Recipients were generally satisfied with the aesthetic result of the procedure, succeeded in integrating the new face into their sense of self within the first few weeks to months post-transplant, and experienced a major and lasting improvement in social integration for years after the transplant. We recommend a systematic reporting of detailed psychosocial evaluations through the use of validated measures administered at regular intervals, to allow for the emergence of a population-level assessment of the psychosocial outcomes of face transplantation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Vascularized composite allotransplantation (VCA) refers to the transplantation of a bloc of multiple vascularized tissues, such as muscle, nerve, skin, bone, and tendon as a functional unit (e.g., hand, face, abdominal wall) from a deceased donor to a matching recipient. Recent advancement in the fields of transplantation, immunology, microsurgery, and regenerative medicine have contributed to the development of VCA as a novel reconstructive option for devastating soft tissue defects involving mainly the face, the extremities and the abdominal wall, thus offering improved functional and cosmetic outcomes when compared with conventional reconstructive techniques.

The most significant indications for VCA as a reconstructive option are severe facial injuries and bilateral hand amputations in victims of battlefield injuries, burns, traumatic events, and cancer—these are typically extensive injuries that cannot be adequately restored using conventional reconstructive options. These types of injury greatly affect the patient’s functionality, psychological condition, and quality of life, thus acting as a harbinger for multiple psychiatric disorders in the long term [1,2,3,4,5,6]. There are potentially millions of patients in the world suffering from these types of injury to the face, extremities, or abdominal wall. For such patients, VCA has thankfully emerged with the potential to provide superior outcomes in a single intervention.

Face transplantation is now considered a viable reconstructive option for severe and devastating facial deformities with successful restoration of appearance and functionality. To date, the literature reports 37 face transplantations performed worldwide with successful and encouraging immunological, functional, and aesthetic outcomes. Patient selection appears to be a critical factor in the success of face transplantation. As such, it entails a pre-operative effort carried out by a multidisciplinary team to ensure that optimal physical, psychological, and social conditions are met prior to face transplantation [7]. In contrast, hand transplantation has been more widely used as a reconstructive option, with over 100 hand transplants performed in the world to date [8, 9]. Teams performing hand transplant interventions stress the importance of patient’s adherence and recommend pre- and post-operative evaluations for successful results.

Previous studies [5, 10,11,12] have found numerous psychological variables that affect surgical recovery and rehabilitation after major surgeries. However, there is no consensus on which specific factors improve post-operative recovery due to both significant heterogeneity between studies, and the inherent difficulty to disentangle post-operative intervention effects from the effects of time, physical recovery, and other post-surgery events. Due to the unique impact of pre-surgery wounds on patients’ appearance, VCA recipients constitute a unique cohort of patients in terms of both pre-operative psychological state and post-operative recovery and rehabilitation. With the hopes of improved quality of life and functionality, these patients submit to lifelong immunosuppressive drug regimens, close follow-up schedules, and frequent monitoring. From the providers’ perspective, this ensures optimal adherence, allows for early management of possible rejection, and contributes to appropriate psychological support. Considering the range of vast face and hand deformities that these patients have before transplant, there is an expectation of improved quality of life after transplantation [7, 8]. So far, most studies have focused on technical aspects of the procedure and very few studies are available about quality-of-life outcomes in face and hand transplant recipients [5].

Methods

Literature Search

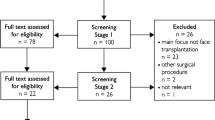

We used the PubMed database to search original studies reporting any measure of mental health, quality of life, or psychosocial outcome in face transplant recipients, dating from the first face transplant case in 2005 to most recent in 2017. We used “Facial transplantation” as our keyword and identified 453 papers. We then restricted our search to studies done in human subjects and written in English. Out of the remaining 354 articles, only 29 reported any measure of mental health, quality of life, and psychosocial outcomes in face transplant recipients. Of these 29 articles, 20 were original studies, three were reflexion papers, and 6 were reviews.

Data Extracted

We extracted the following data from the included articles: where the transplant was performed (i.e., geographical location), which assessment measures were used when applicable, when the data were collected (before and/or after surgery), patients’ demographics, cause of injury, and which outcomes were reported.

Results

We identified 20 original studies reporting at least one measure of mental health, quality of life, or psychosocial outcome in face transplant recipients (Table 1). Of these 20 included studies, seven were done in France, seven in the United States, two in Belgium, two in China, one in Poland, and one in Spain. Assessments were conducted between 3 months and 9 years post-transplant. Reports presented data on male recipients (n = 23) more often than females (n = 9). Injury causes included ballistic trauma, burn (electrical, fire, or acid), animal attacks, and neurofibromatosis type 1. In terms of methods, 11 of the 20 studies reported qualitative assessments of the patients’ psychological outcomes, and nine studies reported results from validated, quantitative assessment measures.

Looking more closely at the quantitative measures used, we noted a weak convergence across studies, with a total of 25 measures for nine studies. Often, studies converged in identifying core outcomes but diverged in the assessment measure they used. For instance, quality of life was assessed in three studies, using three different scales: the University of Washington Quality of Life (UW-QOL) [13, 14], the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF) [15, 16∙∙], and the EuroQol five dimensions/Visual analogue scale (EQ-5D/EQ-VAS) [17, 19]. Similarly, depression was assessed in 4 studies, using 3 different scales: the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [16∙∙, 20, 21∙], the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [18, 19, 22], and the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) [21∙, 23].

There was more convergence in assessing self-reported health, with five studies using the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36; [24, 25]) [14, 16∙∙, 19, 21∙, 26∙∙]; and in assessing interpersonal functioning, with four studies using the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS, 14; [27]) [9, 14, 18, 21∙]—once, in conjunction with the Quality of Relationships Inventory (QoRI) [28] and the Family Assessment Device (FAD; [29, 30]) [21∙]. Beyond these measures, only the Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; [31]) [16∙∙, 18, 19], the Functional Disability Index (FDI; [32]) [33,34,35], and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric interview (MINI; [36, 37]) [14, 35] were used in more than one study.

Among measures used in a single study, we identified three main poles. The first pole included face-injury related measures, such as the Performance Status Scale for Head and Neck Cancer patients (PSS HN) [38], the perception of teasing (FACES-POTS) [16∙∙, 39], the Facial Anxiety Scale-State (FASS) [40], the Physical Appearance State and Trait Anxiety Scale-Self Rated (PASTASS) [41], and the Pain Thermometer [42]. The second pole included measures aimed to assess broad domains of mental health, such as the Spielberg State Anxiety Inventory (SSTAI) [43] and the Subjective Emotional Health (SHE). The third pole included measures assessing resilience and attitude towards the illness: the Dutch Resilience Scale (DRS) [44], the Utrecht Coping List (UCL) [45], the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) [46, 47], the Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale—Self-reported (PAIS-SR) [48], and the Illness Cognition Questionnaire (ICQ) [49]. The detailed characteristics of all aforementioned measures are presented in Table 2.

Qualitative Outcomes

Of the 11 qualitative studies, one was a group study and ten were single case reports—including four from France, two from China, two from the United States, one from Poland, and one from Spain. Overall, these case studies all concluded that patients gradually accepted their new facial appearance and were satisfied with the transplantation. No adverse psychiatric event was reported in any of these studies. Details were not always provided, instead reducing the report of psychosocial outcomes to a very succinct statement. One report stated: “After transplantation, the recipient had a good mental status and accepted his new face easily” [50]. More recently, another report only stated: “The patient saw her face for the first time on day 9 and gradually came to accept it. She has presented no psychiatric events or compliance problems” [51]. When more specific details were provided, they highlighted three main positive psychosocial outcomes for recipients of face transplantation. Patients usually experienced improved social integration post-transplant, were satisfied with the aesthetic result of the transplant, and reported a good integration of the new face in their sense of self.

The main psychosocial outcome of face transplant was repeatedly reported as a rapid and life-changing improvement of the patient’s social life. In the case of the first face transplant recipient, a 38-year-old French female with preserved vision, the report stated: “Psychologically, the transplant was well tolerated in the immediate post-operative period and its quick integration into the patient’s new body image was greatly helped by the fast sensate recovery of its skin surface. At the end of the 12th post-operative week, the patient became able to face the outside world and returned progressively to a normal social life” [52]. These results were maintained up to 5 years post-transplant, when a follow-up study stated: “She gained not only a ‘new’ face but also a ‘new’ life as she started to interact again socially and experienced the absence of reactions of others when going out to the restaurant, shopping, applying for jobs, meeting new people, and traveling abroad” [53]. A similar outcome was observed in a 29-year-old male patient with preserved vision. The study reported that: “Psychological recovery was excellent, with complete social reintegration. […] The patient saw his new face for the first time on day 10 and gradually came to accept it. He has presented no psychiatric events or compliance problems to date. He is able to carry out activities of daily living unassisted and the transplant has reduced his concern about his appearance, which has made having a social life easier for him” [54]. In the United States, identical outcomes were observed in Cleveland, where the first American near-total face transplant recipient was reported as “very excited to re-enter the public arena and [having] regained a large amount of self-confidence since the surgery” [55], and in Boston, where a 59-year-old male patient “returned to his living facility within 5 weeks after the operation and became fully reintegrated into the community with enhanced social capacity.” [56]. In all reported cases, the procedure improved the social integration of recipients.

The second main outcome consistently reported on was patient’s satisfaction with the aesthetic result of the transplant. Because face transplantation is a life-enhancing rather than a life-saving procedure, this was a particularly meaningful outcome. Candidates to the surgery often expect that the transplantation will result in an improvement of their facial appearance and the field can now provide a better projection on this expectation. Indeed, all studies reported that the patients were satisfied. As illustrated in the above quotations, satisfaction with the aesthetic result was often deeply tied to the experienced improvement in the social life of the patients and to the functional result [57]. Indeed, after 18 months, the 38-year-old French female patient stated that “she is not afraid of walking in the street or meeting people at a party, and she is very satisfied with the aesthetic and functional results” [52]. Importantly for long-term prospect, the same patient said that she was “satisfied with her new face and [had] normal social interactions” five years after the transplant [53]. The 41-year-old American female treated in Cleveland was reported to be doing “quite well” and to have become “more ‘picky’ with small aesthetic details as compared with her aesthetic expectations before transplantation” [55]. As for the 59-year-old American male patient, the report stated that one year after the surgery: “The patient was highly satisfied with the esthetic result, and regained much of his capacity for normal social life. […] Our patient’s acceptance of his face transplant and his appearance were unequivocally positive. From the beginning, enhancement of function was his priority, appearance a secondary concern. The patient integrated well into his environment and became more socially active.” [56]. In Spain, the 30-year-old male recipient “said he was pleased with his new appearance” 4 months after the transplant and experienced “no psychological problem associated with his new face” [58]. Across reports, patients were satisfied with the aesthetic result of the transplant.

A third important outcome is the appropriation of the new face into the recipient’s body image and sense of self. Studies did not consistently report on this outcome but some elements could be extracted nonetheless, suggesting an excellent adaptation to the new face. In France, Devauchelle mentioned a “quick integration into the patient’s new body image” 12 weeks post-transplant [59]. After 5 years, the “patient’s new facial appearance is identical neither to that of the donor nor to her own face before the accident. The patient accepted easily her new facial appearance and has been satisfied since the first days” [53]. Petruzzo et al. suggest that this rapid integration of the new face into the recipient’s body image may have been facilitated by the absence of bandages, allowing the patient to see her grafted face every day from the first day after surgery. Lantieri reported that “the procedure had an excellent, positive psychological effect on the patient, with the early, rapid, and full integration of the new face into the patient’s self-image, even before nerve regrowth” [54]. Regarding the 30-year-old Chinese male patient with preserved vision, the report stated: “After the surgery, the recipient soon accepted the new face with the help of psychiatrists and psychologists, and felt satisfied with it. Now the face has become an inseparable part of his body and he will surely cherish it forever.” [60]Footnote 1 As for the 59-year-old American male patient treated in Boston, the study mentioned that “although the donor’s wife reported being able to recognize her husband’s nose in the patient, the patient considered it to be a close match to his original nose in size and shape” [56]. Finally, the Spanish recipient “said he remembers his ‘disfigured’ face but now accepts his new face as his new identity” [58]. Overall, face transplant recipients adjusted very well to their new face and integrated it successfully in their sense of self.

Taken together, qualitative studies concluded overwhelmingly to positive psychosocial outcomes for recipients of a face transplant, in terms of social reintegration, satisfaction with the aesthetic results of the procedure, and integration of the new face in patients’ sense of self.

Quantitative Outcomes

Interestingly, all studies reporting the use of quantitative assessment measures were published after 2011. In contrast, eight of the qualitative studies were published before 2011, and only three after 2011. Quantitative studies provided a finer assessment of psychological outcomes after face transplant surgery and presented a more nuanced picture.

For instance, several studies reported using the Short-Form Health Survey to assess quality of life. This validated questionnaire was used either in its 36-item format or in its 12-item format. Both formats reliably assessed several domains of mental health (mental health, social functioning, vitality, role-emotional) and several domains of physical health (general health, physical functioning, bodily pain, role-physical). A higher score corresponds to better quality of life. Chang and Pomahac reported the scores of three patients, at 3 and 6 months post-transplant. Using the SF-36, they found that the mental health of the three recipients improved continuously. However, using another measure of quality of life concurrently (the EQ-5D/EQ-VAS), they did not find any change. As for the physical health component, it deteriorated at 3 months in all three recipients before raising above baseline level in two out of the three recipients [18]. In the case of a 54-year-old male reported by Lemmens and colleagues, mental health improved from 96.7 before transplant to 98.7 right after transplant, before returning to baseline levels of 95.6 fifteen months post-transplant. The physical health of the same patient improved from 60 to 95 in the same interval, before falling below baseline at 35.6 after 15 months [21∙]. The two male recipients followed by Kiwanuka and colleagues showed different patterns of response. The first recipient experienced a small 3-point decrease in physical health between baseline and 1 year post-transplant, while his mental health increased by 1 point in the same time. The second recipient experienced a large 10-point decrease in physical health, as well as an 11-point decrease in mental health between baseline and 9 months post-transplant [19]. Finally, in the two reports by Lantieri and colleagues, both the mental and the physical components of their patients’ quality of life increased in each recipient, and the same improvement was reflected in another measure (the UW-QOL), although individual differences were reported in magnitude of improvement as well as the presence or absence of depressive and anxious symptoms. Interestingly, Lantieri noted that the improvements in quality of life were linked to improvements in function and aesthetic appearance, and that all patients adjusted to their new faces before full nerve regrowth [14, 26∙∙]. Overall, these quantitative assessments of quality of life demonstrated how variable the levels of quality of life experienced by recipients were over time, as well as the need for better granularity when evaluating quality of life outcomes in face transplant recipients.

Regarding psychosocial outcomes, Coffman and Siemionow reported that their patient’s quality of life in the social domain improved drastically over 3 years, with scores at the PAIS-SR dropping from 15 to 1, indicating successful social reintegration. The Perception of Teasing—FACES (a face transplant-specific measure developed by the authors) allowed them to evidence a sharp improvement in their patient’s experience, with a score falling from 25 to 9 three years post-transplant. To assess patient satisfaction with the aesthetic result, Coffman and Siemionow used an appearance self-rating measure. Their 45-year-old female recipient went from 3/10 before the transplant to 8/10 within six weeks of transplant, and remained stably high at 7/10 three years post-transplant [16∙∙]. Diaz-Siso and colleagues reported high scores of social well-being, at 88/100 two years post-transplant, and 84/100 three years post-transplant [33]. In Belgium, Roche and colleagues reported an absence of psychiatric symptoms based on the MINI and the FDI, and commented: “His participation in family and social activities, which is not affected by the face transplant in any way, has reached similar levels as before the facial trauma. Contrary, the face transplant has given the patient the possibility to reintegrate in the society without feeling stigmatized or experiencing negative social reactions. Strangers see him merely as a blind person as the allograft is hardly noticed. This is in strong contrast with his life after the trauma and before the transplantation, when he never left the house” [35]. These quantifications using different tools all corroborate the qualitative description of a massive positive outcome in the social integration of face transplant recipients.

Finally, quantitative studies provided some assessments of depression and anxiety after a face transplant. Coffman and Siemionow noted a reduction of depressive symptoms from 16/63 (light level on the BDI) pre-transplant, to 6/63 (minimal level) after 3 months, maintained to 8/63 up to 3 years post-transplant, while the Facial Anxiety Scale-State revealed scores reduced by half in the same period [16∙∙]. Lemmens and colleagues found a pattern of improvement post-transplant before a return to baseline in both depression and anxiety levels [21∙]. Kiwanuka and colleagues used the CES-D and found an increase in depressive symptoms in their first patient over 1 year, but a decrease of depressive symptoms in their second patient over nine months [19]. Lantieri and colleagues, who report the death of one patient by suicide at 3.4 years post-transplant, highlighted that psychological outcomes can vary across patients based on baseline levels and psychiatric comorbidity [26∙∙].

Discussion

The face plays a crucial role in our identity and our sense of self. From the portrait of rulers on coins to the photo ID required today every time we must identify ourselves, the face has carried our identity for centuries and is deeply engrained in our culture as a central marker of who we are, in part because our face is not a feature we can easily change. Until 2005, no one had lived with three different faces: a birth face, a disfigured face, and a transplanted face. Face transplant recipients are confronted with unique psychosocial challenges that warrant careful evaluation of mental health, quality of life, and psychosocial outcomes of this procedure. Based on our review of psychological outcomes in recipients of face transplant reported in the literature to date, it appears that recipients are generally satisfied with the aesthetic result of the procedure, succeed in integrating the new face into their sense of self within the first few weeks to months post-transplant, and experience a major and lasting improvement in social integration for years after the transplant.

Improved social reintegration stands out as one of the main positive outcomes of face transplantation. It is therefore important to understand the mechanisms driving this outcome. Patients who elect to undergo a face transplant surgery usually survived an important trauma that left them disfigured. Not only is their facial appearance unrecognizable, it is also often lacking the core features of a human face—eyeballs, nose, or maxillary—in a way that impedes both social interactions and general functioning. Several studies mentioned that social improvement was linked with the functional progress achieved. Fischer and colleagues point to evidence from aphasic patients and patients who have lost the ability to smile to document the strong link between quality of life and the ability to speak [61,62,63,64,65]. Similarly, Petruzzo and colleagues remark: “At present, the patient has a face that can adequately express her feelings and this capacity is important because it plays a key role in how people are seen and perceived by others” [53]. It seems highly possible that the regained ability for the transplant recipients to express themselves, both verbally and through facial expressions, drives this social outcome, which may inform patient selection based on the expected improvement of communication post-transplant.

Because of the heavy medical regimen post-transplant, it is important to assess the impact of face transplant on recipients’ mental health. From our review, we can extract several findings regarding quality of life, depression, and anxiety levels. Importantly, face transplant-specific measures allow for more relevant findings: Coffman and Siemionow highlight that the sharp decrease in face-specific anxiety experienced by their recipient was not reflected in their measure of general anxiety [16∙∙]. Assessing the perception of face-related teasing also revealed the significant improvement experienced by the recipient post-transplant in a uniquely relevant manner for face transplant candidates. In light of these findings, it is possible that results from general trait anxiety measures—showing a gradual return to baseline over time—are missing a lasting reduction of face-specific anxiety post-transplant. A similar concern can be raised about measures assessing quality of life. Each measure focuses on different components of well-being rather than focusing on the specific impact of face transplant on recipients’ quality of life. Additionally, most quality of life and depression measures are impacted by everyday life events unrelated to the transplant (e.g., death of a loved-one). It is therefore possible that important variations in scores over time and inconsistent results across measures could reflect a low specificity of the measures to the effect of the transplant rather than a variable effect of the transplant over time.

Regarding methods, while qualitative studies were the norm before 2011, standards are now shifting towards a more frequent use of validated, quantitative assessment measures. This shift introduced more nuances in the overall positive evaluation of psychological outcomes by highlighting the variability of quality of life across individuals, time of assessment, and measure used. Several important findings have been uncovered.

First, the use of quantitative measures has highlighted the individual differences existing at baseline in quality of life, depression, and anxiety levels. The effect of the transplant can be assessed properly only when individual baseline levels are accounted for, ideally over several baseline time points to document the individual variability of the outcomes of interest before the transplant. The existence of pre-existing psychiatric comorbidity has been found to impact the psychosocial outcome post-surgery [16∙∙, 26∙∙], such that different recommendations may be expected based on the psychiatric history of each candidate.

Along these lines, data from our review suggest that male and female recipients may experience different psychosocial outcomes, thus leading to a different risk/benefit ratio based on the gender of candidates to the surgery. Coffman and Siemionow highlight that male recipients may view their injury differently than female recipients, and that the weight gain due to steroids may impact male and female recipients differently [16∙∙]. Currently, most studies reported outcomes in male recipients. As more studies report outcomes in female recipients, it will become possible to investigate the effect of gender on psychosocial outcomes of face transplantation.

Furthermore, the cause of injury may impact the psychosocial outcomes. Candidates who consider undergoing a face transplant after surviving an accident may have a different psychosocial experience from candidates who survived a suicide attempt versus a criminal assault, or were injured in the course of military duty or an altruistic act [16∙∙, 26∙∙]. Currently, two-thirds of face transplant cases reported in the literature portray ballistic trauma and burn survivors [7]. Yet, preliminary findings may point to reduced social benefits in the case of recipients with a history of self-inflicted gunshot and/or pre-existing mental disorder [19, 26∙∙]. As more data are reported, guidelines for patient selection based on expected outcomes for specific subgroups of candidates will become accessible.

Future Directions

Although qualitative and quantitative studies agree in their positive evaluation of psychological outcomes, the fragmentation of evaluation methods and the lack of systematic reports in what remains a very small group of patients hinder the emergence of a well-documented picture. The fact that only two-thirds of the existing cases are currently reported in the literature is a limiting factor [7]. Only one case study reported psychosocial outcomes in a blind recipient, and this study was the only one assessing psychosocial outcomes in the recipient’s spouse. Another limiting factor—hopefully addressed with time—is that very few studies have access to long-term outcomes yet. This latter point will become even more crucial in the years to come, as the first face transplant recipients approach their 10–15 year post-transplant—a time often critical in solid organ transplants. A detailed understanding of the impact of face transplant on recipients’ mental health, quality of life, and psychosocial outcomes will be necessary then, to assess the procedure against the risk of a possibly limited duration of the grafted face.

In this context, future recommendations focus on four points. (1) We encourage the adoption by more centers of a regular follow-up schedule for psychological outcomes assessments pre- and post-surgery, as more granular assessments revealed significant variability in these outcomes over time. (2) We recommend the use of quantitative, validated measures to document the amplitude of effects observed qualitatively in the clinic. (3) We suggest the standardization, at least for a time, of the measures used across centers, so as to foster a global evaluation of the psychological outcomes of face transplantation around the world. (4) We urge centers to report detailed psychological outcomes systematically to the international VCA registry to contribute to a larger dataset, so that group analyses can be done and contribute to the emergence of norms for patient selection and expected outcomes.

Conclusions

We identified 20 articles reporting at least one measure of mental health, quality of life, or psychosocial outcome in face transplant recipients. Eleven of the included studies reported qualitative assessments of the patients’ mental health, and nine studies used validated quantitative assessment measures—with little overlap in measures used. Both types of studies reported generally positive psychological outcomes. After face transplantation, we can expect to see an improvement of appearance-related symptoms, an improvement of patients’ social life, and a good acceptance of the transplanted face by the patients and their families. No adverse effect has been reported so far on patients’ self-esteem or relationship satisfaction. Assessment of psychiatric symptoms such as depression did not reveal systematic changes post-surgery but must be interpreted with caution due to patient selection bias, individual differences in baseline levels, and pre-existing comorbid conditions. Face-specific anxiety was reduced after face transplantation. Overall, we recommend a more systematic reporting of psychological outcomes across centers, based on a regular pre- and post-transplant assessment schedule, and the use of quantitative measures to complement qualitative observations.

Notes

In qualitative studies, it was not always clear whether the evaluation of psychological outcomes was the opinion of the caregivers’ team or the words of the patient.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: ∙ Of importance ∙∙ Of major importance

Gamba A, Romano M, Grosso IM, Tamburini M, Cantú G, Molinari R, et al. Psychosocial adjustment of patients surgically treated for head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 1992;14:218–23.

Tartaglia A, McMahon BT, West SL, Belongia L. Workplace discrimination and disfigurement: the national EEOC ADA research project. Work Read Mass. 2005;25:57–65.

van der Wouden JC, Greaves-Otte JG, Greaves J, Kruyt PM, van Leeuwen O, van der Does E. Occupational reintegration of long-term cancer survivors. J Occup Med Off Publ Ind Med Assoc. 1992;34:1084–9.

Bonanno A, Esmaeli B, Fingeret MC, Nelson DV, Weber RS. Social challenges of cancer patients with orbitofacial disfigurement. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26:18–22.

Losee JE, Fletcher DR, Gorantla VS. Human facial allotransplantation: patient selection and pertinent considerations. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:260–4.

Bjordal K, Kaasa S, Mastekaasa A. Quality of life in patients treated for head and neck cancer: a follow-up study 7–11 years after radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;28:847–56.

Khalifian S, Brazio PS, Mohan R, Shaffer C, Brandacher G, Barth RN, et al. Facial transplantation: the first 9 years. Lancet Lond Engl. 2014;384:2153–63.

Petruzzo P, Lanzetta M, Dubernard J-M, Landin L, Cavadas P, Margreiter R, et al. The international registry on hand and composite tissue transplantation. Transplantation. 2010;90:1590–4.

Shores JT, Brandacher G, Lee WPA. Hand and upper extremity transplantation: an update of outcomes in the worldwide experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:351e–60e.

Rumsey N, Rumsey N. The psychology of facial disfigurement: implications for whole face transplantation. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep. 2014;2:210–6.

Furr LA, Wiggins O, Cunningham M, Vasilic D, Brown CS, Banis JC, et al. Psychosocial implications of disfigurement and the future of human face transplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:559–65.

Soni CV, Barker JH, Pushpakumar SB, Furr LA, Cunningham M, Banis JC, et al. Psychosocial considerations in facial transplantation. Burns J Int Soc Burn Inj. 2010;36:959–64.

Rogers SN, Gwanne S, Lowe D, Humphris G, Yueh B, Weymuller EA. The addition of mood and anxiety domains to the University of Washington quality of life scale. Head Neck. 2002;24:521–9.

Lantieri L, Hivelin M, Audard V, Benjoar MD, Meningaud JP, Bellivier F, et al. Feasibility, reproducibility, risks and benefits of face transplantation: a prospective study of outcomes. Am. J. Transplant. 2011;11:367–78.

Development of the World Health Organization. WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–8.

∙∙ Coffman KL, Siemionow MZ. Face transplantation: psychological outcomes at three-year follow-up. Psychosomatics. 2013;54:372–8. Provides description and first-use of face-transplant specific assessment measures.

Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen M, Kind P, Parkin D, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil. 2011;20:1727–36.

Chang G, Pomahac B. Psychosocial changes 6 months after face transplantation. Psychosomatics. 2013;54:367–71.

Kiwanuka H, Aycart MA, Gitlin DF, Devine E, Perry BJ, Win T-S, et al. The role of face transplantation in the self-inflicted gunshot wound. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg JPRAS. 2016;69:1636–47.

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiat. 1961;4:561–71.

∙ Lemmens GMD, Poppe C, Hendrickx H, Roche NA, Peeters PC, Vermeersch HF, et al. Facial transplantation in a blind patient: psychologic, marital, and family outcomes at 15 months follow-up. Psychosomatics. 2015;56:362–70. Provides the first joint quality of life assessment of both the blind patient and their life partner.

Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401.

Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: the hopelessness scale. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1974;42:861–5.

Tarlov AR, Ware JE, Greenfield S, Nelson EC, Perrin E, Zubkoff M. The medical outcomes study. An application of methods for monitoring the results of medical care. JAMA. 1989;262:925–30.

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83.

∙∙ Lantieri L, Grimbert P, Ortonne N, Suberbielle C, Bories D, Gil-Vernet S, et al. Face transplant: long-term follow-up and results of a prospective open study. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2016;388:1398–407. Provides long term (longest available to date), quantitative and qualitative assessment of psychosocial outcomes in a cohort of 6 patients, and provides preliminary findings regarding differentiated outcomes based on baseline levels and cause of injury.

Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: new scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J Marriage Fam. 1976;38:15–28.

Pierce GR, Sarason IG, Sarason BR. General and relationship-based perceptions of social support: are two constructs better than one? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61:1028–39.

Paulhus DL, Carey JM. The FAD-Plus: measuring lay beliefs regarding free will and related constructs. J Pers Assess. 2011;93:96–104.

Miller IW, Epstein NB, Bishop DS, Keitner GI. The McMaster Family Assessment Device: reliability and validity. J Marital Fam Ther. 1985;11:345–56.

Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1965.

VanSwearingen JM, Brach JS. The Facial Disability Index: reliability and validity of a disability assessment instrument for disorders of the facial neuromuscular system. Phys Ther. 1996;76:1288–98.

Diaz-Siso JR, Parker M, Bueno EM, Sisk GC, Pribaz JJ, Eriksson E, et al. Facial allotransplantation: a 3-year follow-up report. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg JPRAS. 2013;66:1458–63.

Fischer S, Kueckelhaus M, Pauzenberger R, Bueno EM, Pomahac B. Functional outcomes of face transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:220–33.

Roche NA, Blondeel PN, Vermeersch HF, Peeters PC, Lemmens GMD, De Cubber J, et al. Long-Term Multifunctional Outcome and Risks of Face Vascularized Composite Allotransplantation. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26:2038–46.

Overbeek T, Schruers K, Griez E. Mini international neuropsychiatric interview, Nederlandse versie 5.0.0. Nederland: University of Maastricht; 1999.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatr. 1998;59:22–33.

List MA, Ritter-Sterr C, Lansky SB. A performance status scale for head and neck cancer patients. Cancer. 1990;66:564–9.

Thompson JK, Cattarin J, Fowler B, Fisher E. The Perception of Teasing Scale (POTS): a revision and extension of the Physical Appearance Related Teasing Scale (PARTS). J Pers Assess. 1995;65:146–57.

Gromel K, Sargent RG, Watkins JA, Shoob HD, DiGioacchino RF, Malin AS. Measurements of body image in clinical weight loss participants with and without binge-eating traits. Eat Behav. 2000;1:191–202.

Reed DL, Thompson JK, Brannick MT, Sacco WP. Development and validation of the Physical Appearance State and Trait Anxiety Scale (PASTAS). J Anxiety Disord. 1991;5:323–32.

Herr K, Spratt KF, Garand L, Li L. Evaluation of the Iowa pain thermometer and other selected pain intensity scales in younger and older adult cohorts using controlled clinical pain: a preliminary study. Pain Med Malden Mass. 2007;8:585–600.

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto: Consuting Psychologists Press; 1983.

Wright J, Bushnik T, O’Hare P. The center for outcome measurement in brain injury (COMBI): an internet resource you should know about. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2000;15:734–8.

Schreurs P, Van de Willige G, Tellegen B, Brosschot J. De Utrechtse Copinglijst (UCL). Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger; 1993.

Cloninger CR. A systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants: a proposal. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1987;44:573–88.

Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1993;50:975–90.

Derogatis LR. The psychosocial adjustment to illness scale (PAIS). J Psychosom Res. 1986;30:77–91.

Evers AW, Kraaimaat FW, van Lankveld W, Jongen PJ, Jacobs JW, Bijlsma JW. Beyond unfavorable thinking: the illness cognition questionnaire for chronic diseases. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:1026–36.

Guo S, Han Y, Zhang X, Lu B, Yi C, Zhang H, et al. Human facial allotransplantation: a 2-year follow-up study. Lancet Lond Engl. 2008;372:631–8.

Krakowczyk Ł, Maciejewski A, Szymczyk C, Oleś K, Półtorak S. Face transplant in an advanced neurofibromatosis Type 1 patient. Ann Transplant. 2017;22:53–7.

Dubernard J-M, Lengelé B, Morelon E, Testelin S, Badet L, Moure C, et al. Outcomes 18 months after the first human partial face transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2451–60.

Petruzzo P, Testelin S, Kanitakis J, Badet L, Lengelé B, Girbon J-P, et al. First human face transplantation: 5 year outcomes. Transplantation. 2012;93:236–40.

Lantieri L, Meningaud J-P, Grimbert P, Bellivier F, Lefaucheur J-P, Ortonne N, et al. Repair of the lower and middle parts of the face by composite tissue allotransplantation in a patient with massive plexiform neurofibroma: a 1-year follow-up study. Lancet Lond Engl. 2008;372:639–45.

Siemionow MZ, Papay F, Djohan R, Bernard S, Gordon CR, Alam D, et al. First U.S. near-total human face transplantation: a paradigm shift for massive complex injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:111–22.

Pomahac B, Pribaz J, Eriksson E, Annino D, Caterson S, Sampson C, et al. Restoration of facial form and function after severe disfigurement from burn injury by a composite facial allograft. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:386–93.

Rüegg EM, Hivelin M, Hemery F, Maciver C, Benjoar MD, Meningaud JP, et al. Face transplantation program in France: a cost analysis of five patients. Transplantation. 2012;93:1166–72.

Barret JP, Gavaldà J, Bueno J, Nuvials X, Pont T, Masnou N, et al. Full face transplant: the first case report. Ann Surg. 2011;254:252–6.

Devauchelle B, Badet L, Lengelé B, Morelon E, Testelin S, Michallet M, et al. First human face allograft: early report. Lancet Lond Engl. 2006;368:203–9.

Chenggang Y, Yan H, Xudong Z, Binglun L, Hui Z, Xianjie M, et al. Some issues in facial transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:2169–72.

Lam JMC, Wodchis WP. The relationship of 60 disease diagnoses and 15 conditions to preference-based health-related quality of life in Ontario hospital-based long-term care residents. Med Care. 2010;48:380–7.

Lindsay RW, Bhama P, Weinberg J, Hadlock TA. The success of free gracilis muscle transfer to restore smile in patients with nonflaccid facial paralysis. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;73:177–82.

Hadlock TA, Malo JS, Cheney ML, Henstrom DK. Free gracilis transfer for smile in children: the Massachusetts eye and ear infirmary experience in excursion and quality-of-life changes. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2011;13:190–4.

Borodic G, Bartley M, Slattery W, Glasscock M, Johnson E, Malazio C, et al. Botulinum toxin for aberrant facial nerve regeneration: double-blind, placebo-controlled trial using subjective endpoints. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:36–43.

Dey JK, Ishii M, Boahene KDO, Byrne PJ, Ishii LE. Changing perception: facial reanimation surgery improves attractiveness and decreases negative facial perception. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:84–90.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Bueno and Dr. Pomahac report grants from Department of Defense. Drs. Nizzi, Tasigiorgos, Turk, and Moroni declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical collection on Plastic Surgery.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nizzi, MC., Tasigiorgos, S., Turk, M. et al. Psychological Outcomes in Face Transplant Recipients: A Literature Review. Curr Surg Rep 5, 26 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40137-017-0189-y

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40137-017-0189-y