Abstract

Purpose of Review

Improving diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in Otolaryngology residency programs and in the physician workforce has been at the forefront of many discussions. Despite these important conversations and the noted value of DEI on physician well-being and the elimination of the nation’s health inequities, there has been little improvement. The goal of this paper is to lend a personal narrative to this discussion.

Recent Findings

Prior discussions focus on the percentage of underrepresented minorities in medicine and the strategies and best practices designed to impact these numbers. We want to discuss the impact that being underrepresented had in our journeys to medicine as well as the importance of mentorship, sponsorship, and coaching-especially from those who looked like us.

Summary

The hope is that by hearing these personal narratives there is an increase in awareness, connection, empathy, and mutual respect for the challenges faced by minorities in medicine. That this can lead to introspection and authentic engagement, which can open new opportunities for mutual understanding and provide a space for more diversity of various kinds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

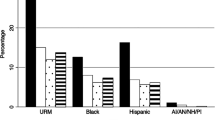

Many discussions of mentorship, sponsorship, and coaching in medicine center on the paucity of underrepresented minorities and the numbers that characterize the blatant dissonance between the United States’ population demographic breakdown and physician representation. According to the United States Census Bureau, the US population is comprised of the following: 75.8% White, 13.6% of Black, 18.9% Hispanic or Latino/a, 6.1% Asian, 1.3% American Indian and Alaskan Native, 0.3% Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander [1]. Yet, the demographic breakdown of otolaryngology head and neck surgery (OHNS) residents stands as 62.4% White, 4.1% Black, 6.3% Hispanic or Latine, 24% Asian, 0.4% American Indian and Alaskan Native, and 0.2% Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander [2]. Although these glaring numbers reveal the longstanding journey ahead towards achieving equity in practice and care, very seldomly do we focus on the personal stories or visions that keep the path lighted towards equity.

In 1979, Audre Lorde, a prominent Black feminist scholar and professor stood before an international delegation of women to deliver one of her most famed speeches, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.”

“In a world of possibility for us all, our personal visions help lay the groundwork for political action. The failure of academic feminists to recognize difference as a crucial strength is a failure to reach beyond the first patriarchal lesson. In our world, divide and conquer must become define and empower” [3].

Her words strikingly identified the lack of Black, poor, LGBTQIA, and marginalized voices and representation in the feminist movement at that time, inevitably disenfranchising the movement from “bring[ing] about genuine change” [3]. So too, must we highlight the personal voices and experiences of underrepresented minorities (URM) to further evoke the critical need for continued diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts.

In this article, you will hear individual testimonies on the impact of being underrepresented in medicine and the impact of DEI on people through their lived experiences. We thought that it would be more powerful to hear first-hand how we can successfully create environments that not only accommodate, but embrace diversity, promote equity, and realize the vision of a culture of inclusion. Through these personal reflections, we hope to normalize diversity, cultivate empathy, and promote the value of mentorship, diversity, and coaching for underrepresented minorities in medicine.

A Medical Student’s Perspective (Katherine Gonzalez)

The path to a career in medicine is long, arduous, and mentally taxing. Thus, there is a need for mentors at every level to help students and trainees navigate around systemic challenges in academic medicine, provide support, and shape them into the next generation of forward-thinking physicians. Great mentors may positively influence the trajectory of a student’s career and impact both their personal and professional development. Accordingly, strong and supportive mentors are invaluable resources in medicine. However, some medical students may find it more difficult than others when trying to find the right mentor. For students who are underrepresented in medicine (URM), mentors are not always readily available. Firstly, significant disparities exist in the physician workforce in the United States by race and ethnicity [4]. Predictably, these disparities are also visible when looking at matriculation rates for medical students by race. Ethnic and racial representation among physicians is one of several critical factors that influence a URM medical student’s desire to pursue a given specialty [5•]. Specialties such as Family Medicine and Obstetrics & Gynecology have higher rates of URM applicants and are more diverse compared to Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery (OHNS) [6]. OHNS is one of the most competitive specialties in medicine and having mentors that can guide and support URM students towards a successful match is paramount. A survey conducted by Johnson and colleagues, found that students were dissuaded from applying to OHNS residency programs due to lack of mentors of the same race or gender in the field [7]. Another study found that assigning mentors to medical students for the duration of an OHNS clinical clerkship increased the likelihood of URM medical students retaining an interest in OHNS and successfully matching into residency programs [8]. Finally, in a recent survey administered to URM students, Thompson-Harvey et. al, arrived at the conclusion that medical students with an early exposure to OHNS, clinical opportunities, and positive role models were more likely to pursue OHNS as a career [5•].

High school pipeline programs have been developed to provide underrepresented students with early exposure to surgical specialties, to increase the number of URM surgeons in the physician workforce in the United States [9]. These programs are structured to teach students surgical skills and techniques as well as provide early longitudinal mentorship. Additionally, numerous college internships exist to serve the same goal of increasing recruitment and retention of URM students in medicine and surgical fields. Though these programs are great in theory, more work is needed to address all barriers that may impact a student’s career path in OHNS.

As a minority student from a medically underserved community, I encountered several hurdles before I even began my journey in medicine. Coming from a large family and a financially insecure household, I worked two jobs to afford my college education. This alone almost entirely disqualified me from participating in short-term programs aimed at providing URM students with early exposure to surgical fields like OHNS because I couldn’t afford to quit my jobs. Second, my socioeconomic status impacted my choice of college. I enrolled in a smaller university that was more affordable for myself and my family. Unlike my peers, my university did not have the resources or mentors to help provide guidance on my path in medicine. I did not know anyone who personally attended medical school, nor did I have any physician mentors to ask for advice. These factors and more would later affect my medical school selection. I found myself at a newly established and accredited medical school in California that lacked a home residency program in OHNS. Without a home program, there was no OHNS faculty to mentor me and very little clinical exposure due to the lack of formal rotations.

As a woman and underrepresented medical student, I have found it extremely difficult to find mentors with whom I personally identify and share similar scholarly and clinical interests. Recently, I was fortunate to meet one of the most influential people of my life to date, Dr. Tammara Watts. Dr. Watts is a surgeon-scientist in the Duke Otolaryngology Department that allowed me the opportunity to conduct basic science research in her lab and to aid me in gaining clinical exposure and access to other mentors. These are experiences that I would have never received at my home institution, and they have been instrumental to me pursuing a career in OHNS. Medical school and residency programs that are diverse and encourage a sense of community by supporting students with programs or initiatives that foster inclusivity and equity are more likely to attract and retain trainees from minority groups. If your home institution does not offer mentorship or if the mentors and sponsors are not providing you what you are looking for, I recommend looking for support elsewhere. Many of the organizations, such as the American Academy of Otolaryngology, offer mentorship programs designed to connect student members with Otolaryngologists across the country. In addition, many of the providers who enjoy mentoring, have social media pages that offer advice that you can access in your own time. You can also reach out to anyone via email and ask if they would be willing to meet with you and to provide mentorship.

A Resident’s Perspective (Somtochi Okafor)

Each mentor, leader, and visionary who has helped guide me towards this path has reminded me that statistics merely provide an objective glance into the arduous and complex voyage of achieving DEI in OHNS residency.

Prior to applying to OHNS residency, the chance encounter of hearing Drs. Romaine Johnson and Larry Myers speak about the history and innovation of OHNS during a Student National Medical Association (SNMA) meeting prompted my decision to enroll in an OHNS elective rotation. During that rotation, I was assigned to Dr. Ashleigh Halderman’s skull base room where I witnessed a transsphenoidal pituitary resection for the first time and was exposed to the variety and depth of anterior skull base surgery, a field that merely one year prior I was not aware existed. Such experiences not only exposed me to OHNS but also granted me an opportunity to receive mentorship from attendings who inevitably inspired and encouraged me to apply to OHNS despite the daunting statistics. Their willingness to provide insight into their respective journeys as well as guide me as I embarked on my own, truly served as a catalyst for inspiration as well as illustrate the key mentor characteristics trainees seek: approachability, genuine caring and supportiveness [10••, 11].

In residency, mentorship has continued to serve a fundamental role through both formal and informal programs at my institution. Whether formal or informal, mentorship remains an invaluable asset that is shown to yield “an important influence on personal development, career guidance, career choice, and research productivity, including publication and grant success” [12]. Even more so, mentorship is essential for URM residents and is likely to increase career pursuits in academic medicine where there remains a dire need for adequate representation of URM faculty [13]. Although URM residents often seek racial, ethnic and gender concordance when selecting mentors, they experience difficulty in doing so due to the lack available URM OHNS faculty. Mentorship discordance across race, ethnicity, or gender, however does not limit the impact a mentor has on a resident [10••, 13]. From my perspective, there is serenity in confiding in a mentor and role model who understands the nuanced experiences I face as a Black woman; however, there too is beauty in the guidance and care I receive from mentors who do not share my racial or gender background. Resources such as Osman and Gottlieb’s MedEdPORTAL publication, “Mentoring Across Differences,” offers faculty-oriented mentorship training across various sociodemographic differences [14]. Ultimately, the empowerment I experience from my mentors truly encourages and strengthens me to grow as not only a resident but as a future mentor.

Though this is my personal experience and voice as a URM resident, it remains crucial for us to highlight our voices in this journey to establishing DEI within OHNS. We should not solely rely on objective statistics that dehumanize the lived stories of inequity in medicine. Rather, like Audre Lorde emphasized, we must define and empower our personal visions to lay the groundwork for change.

An Associate Vice Chair of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion’s Perspective (Trinitia Y. Cannon)

My entire life I was always ‘the first,’ ‘the only’ or at the very least, ‘one of the few.’ The first in my family and circle of friends to go to college. The only Black person in my undergraduate honors program and the only pre-med student of color. It was no surprise that I was the only underrepresented minority to choose the competitive road that is Otolaryngology. Despite my academic success, I still received feedback that dissuaded me from pursuing a surgical career. None of this was a deterrent. Being the only minority in my intern class was neither a shock nor a burden. It was simply the norm.

I was fortunate that I never felt the burden of being unsupported. I had long ago accepted that people would consider me an underdog and that it was simply my job to prove them wrong. I never thought that I was fighting for my race. It was enough to fight that fight for my own survival. Once I knocked down the obstacles in my path, everyone standing behind those doors put the full weight of their support into seeing me succeed. Never in my journey did I have to question “how will I be supported” in my residency program.

A lot of URM minorities don’t feel supported in their training program. This was never my burden. When Harold Pillsbury, MD, invited me to interview for a residency position, he took me by the hand and introduced me to the faculty individually. He applauded my prior accomplishments. He told me, unprompted, exactly what he would and could do for my career, if I trusted him with it. Never once did I fear being dismissed from my program just for being born Black. While I felt safe and protected, this is not the case for many underrepresented residents. In 2015, according to an unpublished analysis by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, while Black residents account for about 5% of all residents, they represent nearly 20% of those who are dismissed [15].

Residency recruitment directed specifically towards people of color was not discussed during my time as a resident in the way that it is today. Today, it feels like an obligation, a burden, a fight to get one’s peers to understand the impact of having a diverse program. My former chair, Dr. Pillsbury, made it seem effortless. He knew that it was important for the doctors in our department to look like the patients that they cared for. He adopted a recruitment strategy that was directed and supported from the top down in what seemed like a natural process.

I had mentors of every kind who poured into me. Robert Buckmire MD, co-author on this paper, was one. Early in my career he was the only mentor that I had that looked like me. It is difficult to impart how important this is. There is nothing like the person who truly understands because they have similar lived experiences. He is the only person that I could have certain conversations with. I could confide in him what it was like to be a woman of color in a white, male-dominated field. I could talk to him about how certain biases or racist acts could erode at my confidence, even when everything else is going well. Having mentors that look like you has many positive effects. Fortunately, Dr. Pillsbury recognized this. Midway through my residency, Dr. Pillsbury proposed, against the wishes of many of the faculty, that all 6 of his URM residents attend the Caribbean Association of Otolaryngology annual meeting in Suriname. This was such an amazing opportunity. At this meeting I met EVERY Black Otolaryngologist who has helped to shape my career to this day. In fact, my current chair and co-author on this paper, is someone I met at that meeting. Dr. Pillsbury has been a prominent figure in my career, and he went from being my mentor to my sponsor. Throughout my career, not only did he offer sage advice, but he also recognized opportunities that would be of benefit to my career goals and made a point of putting my name up for each of them. He made calls on my behalf and made sure that my career was exactly what I wanted it to be. From my first job to my seat as an oral board’s examiner, he was one of key figures that helped me become successful. When I took my current job at Duke, he called my boss to discuss my career. My boss called me after they talked. I have been fortunate in having many mentors and sponsors with Drs. Marion Couch and Jesus Medina to round out the people that I still turn to today.

In my current role as Chief of the Head and Neck Division and as the Associate Vice Chair of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, I now have the unique opportunity to have an impact on my entire department. These opportunities come in the form of normalizing diversity, cultivating empathy, and establishing new competences via a mosaic of influences centered around mentorship, sponsorship, and coaching. I have been able to use my leadership education to coach peers and mentees develop methods to counter the cumulative effects of micro and macroaggressions encountered from patients, staff, colleagues, and leadership. The hope is that these sustainable efforts have an impact on recruitment and retention at all levels of our department. Dr. Okafor and I are leading such efforts by establishing and launching a curriculum focusing on racism, DEI, and decreasing health inequities. In addition, I am building community partnerships designed to mitigate health disparities.

A Program Director’s Perspective (ROBERT BUCKMIRE)

A residency Program Director (PD) is uniquely positioned to play a central role in both mentorship and sponsorship for all post graduate trainees, specifically URM individuals. In my institution, I assigned myself (as PD) as the initial mentor to all incoming residents, with the discrete intent of normalizing the mentor/mentee relationship early within the surgical residency training paradigm. These early interactions allowed me to appreciate the variable resources, and life circumstances of our URM residents on a one-to-one basis. It is my firm belief, that on this inceptive level, mentorship should be individualized rather than uniform.—Accordingly, for many of my URM mentees, mentorship involved sharing my own personal, resonant URM narratives– that may or may not be pertinent in other non—URM-mentor/mentee relationships.

The PD role is also an ideal position from which to encourage meaningful interactions and activities for residents who might not otherwise independently avail themselves. In this capacity, sponsorship opportunities abound. A PD is frequently called upon to sponsor/nominate candidates for institutional, regional, or national roles, providing unique opportunities for both professional affiliation and recognition. On an institutional level, occasions for involvement in impactful committees such as house staff council arise regularly. These opportunities extend to regional and national levels as well. For example, on one occasion several URM residents from my institution were nominated for and permitted time off to participate in a diversity panel at a national meeting. Ironically, while these events offer precious, and invaluable chances for professional collaborations and networking, they may concurrently impose unwelcome additional stressors and work burden upon the recipients. Mentors must remain mindful of inadvertently imposing our own "Minority tax" upon URM individuals.

Coaching opportunities arise organically, as a part of the ongoing training relationship. To optimally leverage these opportunities, however, a PD must maintain a real-time understanding of a coachee’s professional interactions—which requires regular check-ins. That said, coaching may take place in exchanges as trivial as advising a coachee regarding the best candidate and approach with which to solicit faculty members for participation in a research project. Coaching occurs on a larger, national scale as well. Through programs such as the SUO Diversity Committee URM mentorship program, I have had the occasion to coach multiple URM medical students from other academic intuitions in preparation for impending residency interviews.

All the above elements must be thoughtfully navigated by individuals in the impactful role of Program Director, and ideally brought to bear for successful promotion and retention of URM trainees.

A Chair’s Perspective (HOWARD FRANCIS)

Contemporary efforts to advance diversity, equity and inclusion represent a chapter in the American Story that sets the stage for the full realization of our potential as a nation. The specialty of OHNS is striving for a workforce that is more aware of health and healthcare needs of a diverse population, some of which results from a legacy of racism, under-investment, or other marginalizing practices. One of the most important means is to increase representation by professionals from these under-served populations. As a microcosm of the society, departments and institutions contain remnants of the attitudes and structural barriers that will prevent progress in this area. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. provided the vision of a “mountain top” that we all aspire to, but as we encounter rough terrain on this arduous climb, a combination of intentional leadership, community support and personal grit keeps us on a path to resolving persistent inequities.

Intentional leadership emerges from openness and curiosity about experiences other than one’s own, from which flows an understanding that some have larger boulders to climb and deeper canyons to cross. Being underrepresented in medicine poses the burden, for example, of constantly needing to prove oneself as being worthy, and sometimes setting unreasonably high expectations with the hope of being counted among the chosen. A chronic hypervigilance ensues that leaves one in defense mode against anticipated and experienced scrutiny, and not-so-subtle questioning of one’s credibility. Facing a variety of micro-aggressions and experiences of imposter syndrome may lead to a variety of psychological outcomes depending on personal resilience, availability of support from others and the general culture of inclusivity.

Ultimately responsible for setting expectations and modeling behaviors that shape the service and learning culture, the Department Chair or Division Chief in concert with senior faculty and staff, must establish the conditions of psychological safety that allow individuals to bring their authentic selves to the daily work and to constructively navigate encounters that challenge their sense of belonging. There is a certain humility required to be a transformative leader in this space. Someone whose authentic curiosity and empathy leads them to ask uncomfortable questions and receive uncomfortable answers that enrich their understanding about how the world outside of their own comfort zone operates. And from this process of discovery should arise an appreciation of how a diversity of experiences contributes to a broader definition of accomplishment, impact and value beyond narrow standards that reflect prevailing biases in the house of medicine and the broader society.

Foundational tactics required to create a culture in which diversity thrives and yields benefits, include first, the promotion of a common vision that also speaks to the value of varied experiences and perspectives. Second, there is the need to develop a shared understanding of values-based leadership. Third, it is necessary to engage in activities that utilize these concepts to build trust, mutual understanding, and a roadmap to constructively addressing misunderstandings and conflicts. Stories are powerful tools for building empathy and should be leveraged through such activities as book clubs, grand round presentations and sharing between co-workers. Unprofessional behavior is a major threat to trust and psychological safety, particularly if it goes unaddressed. Failure to address bullying, incivility and worse will eliminate any efforts to develop a positive work environment, and individuals who belong to traditionally marginalized groups will feel particularly vulnerable in these environments. The inability to bring one’s authentic best self to work or study every day will be a major impediment to a sense of belonging with the freedom to take risks. The result is an inability to flourish as a full participant in the creativity of the team as it solves problems. The resulting failure to fulfil our potential to innovate is a shared loss to our teams and institutions.

The chair must cultivate the working relationship across the department that supports diversity and psychological safety. This is aided by keeping a finger on the pulse of how faculty and trainees are feeling in terms of their sense of purpose and belonging. It is also necessary to regularly provide feedback to senior faculty as culture agents, and opportunities for their skill development and coaching when appropriate. It is helpful to have a values-based framework that informs the approach to leadership and sustenance of a supportive culture. Our department has a 12-year history of leadership development, not necessarily focused on DEI, but providing a conceptual framework that lends itself well to the principles of DEI [16].

Despite the reality that many decades of systemic subjugation have affected representation and patient health outcomes, there is increasing politicized debate on the relevance of DEI in the classroom, workplace, and our society. Medical education and practice have stood at the forefront of discrimination as evidenced by past segregation, Jim Crow laws, and the 1910 Flexner Report. Commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation and conducted by Abraham Flexner, this national survey of American and Canadian medical schools led to the closure of 5 out of 7 historically Black medical schools in the United States; thus, leaving Howard University College of Medicine and Meharry Medical College as the only medical institutions in which Black medical students could train, inevitably limiting the education and training of Black physicians for years to come [17, 18]. These vestiges remain glaringly present today through implicit bias and racial/ethnic, gender and socioeconomic health inequities affecting patients [18, 19]. Thus, to address and rectify this past, we must integrate DEI at the forefront of discussions involving recruitment, retention and promotion of those underrepresented in medicine.

DEI remains a critical element of medical education, residency training, and faculty development. Each level of medical education, training and development warrants a specific focus of DEI initiatives. URM medical students and residents rely on strong foundations of mentorship to guide them through the bottleneck phases of medical training that will open the opportunity to establish themselves as future otolaryngologist head and neck surgeons. As one continues through the academic ranks, sponsorship and faculty development opportunities further allow for continued growth and navigation through the “labyrinth” of academic medicine and a trajectory for successful academic career [20••]. Without DEI measures including mentorship, sponsorship, and coaching, the gaps in representation and health outcomes further widen and cast doubt on the potential of realizing equity in the United States.

Although the narrated truths we have highlighted represent a non-exhaustive myriad of lived experiences and current paths of those underrepresented in medicine, they serve as reminders that behind each statistic and paucity of representation there remains a dire need to humanize the voices that unfortunately have been systemically silenced for many years. Efforts to remedy years of systemic silence include pipeline, mentorship and sponsorship programs at the department, institutional and national levels. Substantial research in this realm continues to reveal the impact these programs impart on URM students, residents and faculty presence in OHNS, research productivity, and long term careers in academic medicine [5•, 7, 9, 20••]. However, without efforts and initiatives that continue to challenge our complacency with the stagnation of representation, we will not achieve health equity.

Data Availability

All data reported in this paper were obtained from prior studies, which are listed in the references below.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Bureau USC. Quick Facts United States Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/RHI125221. Accessed 01 Feb 2023.

Association of American Medical Colleges. Table B5. Number of Active MD Residents, by Race/Ethnicity (Alone or In Combination) and GME Specialty. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/interactive-data/report-residents/2021/table-b5-md-residents-race-ethnicity-and-specialty.

Lorde A. The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches: Crossing Press, 1984:110–114.

Mora H, Obayemi A, Holcomb K, Hinson M. The National Deficit of Black and Hispanic Physicians in the US and Projected Estimates of Time to Correction. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2215485.

• Thompson-Harvey A, Drake M, Flanary VA. Perceptions of Otolaryngology Residency Among Students Underrepresented in Medicine. Laryngoscope. 2022;132:2335–43. Findings from this study show the value that race concordant mentorship and meaningful relationships has on the choice for OHNS residency.

Lopez EM, Farzal Z, Ebert CS Jr, Shah RN, Buckmire RA, Zanation AM. Recent Trends in Female and Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups in U.S. Otolaryngology Residency Programs. Laryngoscope. 2021;131:277–81.

Nellis JC, Eisele DW, Francis HW, Hillel AT, Lin SY. Impact of a mentored student clerkship on underrepresented minority diversity in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:2684–8.

Lane JC, Shen AH, Williams R, et al. If You Can See It, You Can Be It: Perceptions of Diversity in Surgery Among Under-Represented Minority High School Students. J Surg Educ. 2022;79:950–6.

Ramirez AV, Espinoza V, Ojeaga M, Garza A, Hensler B, Honrubia V. Home Away From Home: Mentorship and Research in Private Practices for Students Without Home Programs. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;1945998221120231.

•• Cabrera-Muffly C. Mentorship and Sponsorship in a Diverse Population. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2021;54:449–56. This article defines mentorshop and sponsorhip and the current state of these within Otolaryngology as well as the strategies for being an effective mentor and mentee.

Gurgel RK, Schiff BA, Flint JH, et al. Mentoring in otolaryngology training programs. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;142:487–92.

Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marušić A. Mentoring in Academic MedicineA Systematic Review. JAMA. 2006;296:1103–15.

Yehia BR, Cronholm PF, Wilson N, et al. Mentorship and pursuit of academic medicine careers: a mixed methods study of residents from diverse backgrounds. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:26.

Osman NY, Gottlieb B. Mentoring Across Differences MedEdPORTAL. 2018;14:10743.

William Mcdade M, PhD. Diversity and Inclusion Graduate in Medical Education: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, 2019.

Schulz K, Puscas L, Tucci D, et al. Surgical Training and Education in Promoting Professionalism: a comparative assessment of virtue-based leadership development in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery residents. Med Educ Online. 2013;18:22440.

Laws T. How Should We Respond to Racist Legacies in Health Professions Education Originating in the Flexner Report? AMA J Ethics. 2021;23:E271-275.

Steinecke A, Terrell C. Progress for Whose Future? The Impact of the Flexner Report on Medical Education for Racial and Ethnic Minority Physicians in the United States. Acad Med. 2010;85:236–45.

Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and Implicit Bias: How Doctors May Unwittingly Perpetuate Health Care Disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1504–10.

•• Francis CL, Villwock JA. Diversity and Inclusion-Why Does It Matter. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2020;53:927–34. This article discusses the reasons why Otolaryngology has historically lagged behind other specialties with respect to diversity and strategies on DEI programs.

Funding

KG is funded by the NIH NIDCD's Mentored Research Pathway for Otolaryngology Residents and Medical Students: R25 Program R25DC020172.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SO, KG, RB, TC, and HF all contributed equally to the manuscript. All wrote and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Trinitia Y. Cannon reports consulting fees from Cook Medical, honoraria from the University of Rhode Island and the University of Oklahoma. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Okafor, S., Gonzalez, K., Buckmire, R. et al. Mentorship, Sponsorship, and Coaching to Increase Recruitment, Retention, and Belonging. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep 12, 90–96 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40136-024-00509-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40136-024-00509-1