Abstract

Purpose of the Review

The purpose of this review is to emphasize the implementation of strategies and initiatives to develop early career pathways to otolaryngology-head and neck surgery (OHNS) for individuals underrepresented in medicine (UIM).

Recent Findings

Recent studies have shown that clinical experience, early exposure, and mentorship play an influential role in a student’s decision to pursue a medical specialty.

Summary

Diversity in healthcare has been shown to help promote greater healthcare outcomes and address health disparities. To create a workforce that reflects the diversity of the US patient population, intentional initiatives and early pathways must be developed to support students UIM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

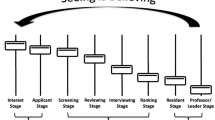

Throughout medicine in the USA, the demographics of the physician workforce do not match that of the population. Individuals underrepresented in medicine (UIM)—defined by Black, Hispanic/Latino, mainland Puerto Rican, Native American, Alaskan Native, and Native Hawaiian [1]—compose a mere 11% of the physician workforce [2] despite comprising 35% of the US population [3]. This lack of diversity is emphasized further within surgery and surgical subspecialties, including within otolaryngology-head and neck surgery (OHNS). UIM students have been underrepresented in OHNS residency applications: < 7% for Black students and < 10% for Hispanic students each year from 2018 to 2022 (Fig. 1) [4]. This propagates further following medical education. For example, in 2019, 6.2% of resident trainees and 4.1% of full professors were Hispanic while 2.3% of resident trainees and 1.7% of full professors were Black [5].

Percentage of applicants by race/ethnicity to otolaryngology residencies from 2018 to 2022 according to ERAS Data [4]

The benefits of diversity in the physician workforce have been well documented, specifically regarding the positive impact on patient care. UIM physicians are more likely to serve low-income, Medicaid, and uninsured patients and are more likely to practice medicine in underserved areas [6,7,8,9]. Racial/ethnic minority patients often seek care from and report greater satisfaction with their care when it is provided by racially/ethnically concordant physicians, and they are more likely to participate in clinical trials if the team of investigators is comprised of diverse members [10,11,12,13,14]. In regard to medical education, diversity in the physician workforce improves the awareness and education experience of non-minority trainees and creates higher-performing teams [15]. To improve patient outcomes, increase health care equity, and optimize health care teams, increasing the diversity in the physician workforce is of paramount importance.

Early pathways must be developed and supported for premedical students and beyond in order to create a sustainable pipeline of UIM students to OHNS [16••]. The aim of this review is to describe strategies to increase the UIM student pipeline to OHNS through the provision of early exposure to the field, early involvement in research, and early mentorship and career development support (Table 1).

Early Clinical Exposure to Otolaryngology

Required Medical School Clerkships

During medical school, clerkship rotations are an essential time for hands-on exploration of medical and surgical subspecialties. The power of exposure alone can impact a student’s career trajectory. In a recent survey by Faucett et al. of African-American practicing otolaryngologists, 67% of respondents selected OHNS because they enjoyed it during their medical school clerkship, and early exposure to the field was a major driver for their career choice [17]. It should be noted that many medical students have limited exposure to surgical subspecialties such as orthopedic surgery, plastic and reconstructive surgery, ophthalmology, urology, and OHNS because they are not required in the general medical school curriculum [18]. In fact, the Association of American Medical Colleges reported a decline in medical schools requiring surgical specialty education from 33% in 2017–2018 to 26% in 2019–2020 [19]. This presents a tangible area for action. In the orthopedic surgery literature, London et al. report the positive impact of a required musculoskeletal (MSK) clerkship at a single institution on the diversity of the applicant pool to orthopedic surgery residency [20]. Retrospective survey data from students who were required to take a 1-month MSK clerkship compared to those who were not demonstrated that 88% of students were positively influenced to apply to orthopedic surgery residency. Among UIM applicants, there was a 101% relative increase in the proportion of applicants to orthopedic surgery following the implementation of the required clerkship. Bernstein et al. also demonstrated that students who participated in required musculoskeletal clerkships had a higher rate of applications to orthopedic residency programs versus students who did not [21]. In a survey of 122 U.S. medical schools in 2002, 55% of 16,294 medical school graduates had required MSK coursework [21]. For UIM students with required MSK coursework versus without required coursework, the rate of application to orthopedic surgery residency was 8.2% and 6.1%, respectively [21]. Required clerkships in OHNS (and other surgical subspecialities) should therefore be considered across medical schools to help address the lack of UIM diversity in the field.

Partnerships with Medical Schools Without OHNS Departments

A student without an OHNS home program faces a multitude of obstacles. For example, the inability to obtain early exposure to and mentorship within OHNS impacts the intensive academic portfolio often required to match. Barring the competitive nature and limited residency positions in this specialty, the absence of a home residency program, a network, and research opportunities can be particularly limiting in nature. Oftentimes, students without a home program must search for support, either through local otolaryngologists in private practice or local institutions, while simultaneously completing their required coursework [22]. Furthermore, the lack of home OHNS programs at all four historically Black medical colleges; Meharry Medical College, Howard University College of Medicine, Morehouse School of Medicine, and Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science propagates a barrier for UIM students entering OHNS. This offers a tangible area for action. Partnerships with local and regional academic institutions with OHNS departments along with national OHNS societies can be developed and bolstered. Partnerships across institutions have been previously described (i.e., Meharry-Vanderbilt Alliance, Howard and Georgetown Memorandum of Understanding, etc.) to bolster collaborative research efforts and community engagement. However, formalized partnerships regarding medical student-required clerkships, involvement in OHNS student interest groups, provision of resident and faculty mentorship, and opportunities for research across institutions would be invaluable.

Collaborative Nationwide Initiatives

Nationwide initiatives—led by OHNS national societies in collaboration with medical institutions, undergraduate programs, and high schools—such as summer internship programs and virtual platforms provide significant opportunities for early exposure to and career development in OHNS. In the orthopedic literature, Mason et al. describe an 8-week clinical and research summer internship in orthopedic surgery geared specifically for medical students [23]. First-year medical students of all races/ethnicities can apply for the program which includes MSK lectures, hands-on workshops, research projects, mentorship, and counseling throughout the remainder of each participant’s medical school career. Between 2005 and 2012, 118 medical students completed this program. The racial/ethnic composition of the participating medical students was 69% Black (n = 82), 14% Latino (n = 16), 9% White (n = 11), 5% Native American/Indian (n = 6), and 3% Asian (n = 3) [23]. Completion of the summer internship program was associated with increased odds of applying to an orthopedic surgery residency. For example, for UIM students, 31% of participants (n = 15 of 48) applied to orthopedic surgery residency vs 3% of UIM nonparticipants nationally (n = 782 of 25,676; odds ratio, 14.5 [95% CI, 7.3–27.5]; P < 0.001) [23]. The match success rate was 76% for participants of this summer internship program. Virtual platforms should also be exploited to maximize outreach potential to UIM students nationwide. For example, a collaboration with the student interest groups from Meharry, Morehouse, and Howard medical schools, the Student National Medical Association (SNMA) Otolaryngology Student Interest Group, and Harvard Medical School/Massachusetts Eye and Ear birthed a novel program. The “SNMA-Harvard: Is Oto in Your Future?” program created a platform to increase the visibility of OHNS to UIM students. This alliance has generated invaluable avenues for mentorship, research, and networking. Similarly, programs to “leverage the virtual landscape” have provided informational sessions to introduce OHNS, Diverse Equity Inclusion (DEI) initiatives on social media and provide virtual mock interviews for interview sessions [24, 25••,26]. These platforms have increased accessibility and the range of students that can be reached. Overall, virtual platforms have been shown to be invaluable in engaging and connecting students with the necessary resources to succeed.

Funded Elective Visiting Clerkships

Mentored clerkship opportunities have increased medical student interest in residency training programs and provide a platform for students to ascertain a particular interest in academic medicine. Many institutions and national professional organizations have established funded visiting clerkships to support and address financial barriers students may face [27]. Common support includes a waived registration fee, compensation, and/or a housing stipend provided upon acceptance [28]. For example, the American Association of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery established the Diversity Endowment URM Away Rotation Grant which provides $1000 to use toward travel, housing, or food during their clinical rotation. Similarly, the Society of University Otolaryngologists (SUO) has also established the URiM Away Rotation scholarship which provides funds up to $2000 for students during their clinical rotation. Various institutions have followed suit to establish affordable opportunities for students to gain clinical and research training.

Early Exposure to Research in Otolaryngology

Early exposure to research is essential for students pursuing OHNS. Academic productivity or clear dedication to scholarly pursuits is often a metric of interest for students applying to OHNS. In addition to contributing to the literature, the benefits of student participation in research are innumerable, including the ability to formulate a hypothesis, develop sound investigative methods, and explore the process of answering a research question. In addition, student research projects provide an opportunity to enhance oratory presentation skills and connect with mentors. Research mentors may also serve as advocates and letter writers in the residency match process. Unfortunately, the lack of diversity that is seen in medicine extends to physician-scientists starting early in training. From 1975 to 2014, 10,000 MD-PhD students graduated from medical science training programs—3.7% of graduates were Black students and 4% were Hispanic students [29]. When one looks ahead to CORE grant and NIH grant funding, disparities persist in regard to lack of funding for UIM individuals [30••]. For example, a review of CORE grant recipients in 2010 demonstrated 2.2% were Black and 2.2% were Hispanic while in 2019, 3.0% were Black and 0.0% Hispanic [30••]. Among faculty across academic medicine, UIM people make up only 2.8%, 2.1%, and 1.0% of funded early-stage, new, and experienced investigators [29]. As such, it is important to create pathways, initiatives, and programs that provide early opportunities to develop and hone research technical skills while connecting with mentors. Initial interest in research can be inspired through invitations to UIM undergraduate and medical school students to participate in journal clubs and didactics hosted by OHNS departments. Other actionable approaches include scholarship-based research externship programs, funding opportunities for summer research via national professional societies, virtual research opportunities, and institutional/national professional society-funded support for conference attendance/presentations. As research acumen is often used as a barometer for student and academic success, it is important to create opportunities for UIM students to explore this aspect of the field of otolaryngology.

Early Mentorship and Career Development

Early access to dedicated mentorship and career development is vital for students considering OHNS. The reputation OHNS has as a competitive, highly selective surgical subspecialty may serve as a deterrent to student interest—including UIM students [31]. Therefore, early mentorship can guide and encourage students to consider a career in OHNS. Formalized mentorship programs have yielded great success in developing young UIM surgeons in academic surgery, exemplified in the general surgery literature. Butler et al. describe the development of the Diverse Surgeons Initiative—a program that comprises three 2-day sessions over a 9-month period which provided UIM general surgery trainees with fundamental surgical techniques, anatomy review, disease pathophysiology lectures, and case-based preparation for yearly in-service examinations—to increase UIM representation in minimally invasive surgery and best prepare trainees for success in fellowship and beyond [32]. This program however grew to include UIM trainees (nominated for this program by their program directors) and young faculty with interests outside of minimally invasive surgery due to the offered mentorship and career development for success in academic surgery. A review of the graduates from the Diverse Surgeons Initiative from 2002 to 2009 demonstrated that 99% completed general surgery residency; 87% completed fellowship training; 50% received a fellowship in the American College of Surgeons; 41% served in faculty positions; and 18% served in leadership positions. Consideration of a similar OHNS initiative with the support of an OHNS national professional society has the potential to have a significant impact on UIM students, trainees, and junior faculty in OHSN. The mentorship was also vital to the overall experience of students during a visiting clerkship in OHNS, as described by Nellis et al. [27]. Based upon early subspecialty interests, UIM students were assigned to mentors during the clerkship, creating opportunities for research collaboration and discussions regarding long-term career goals. Of the 15 students who participated in the clerkship, 7 students went on to apply to OHNS residency programs, and 6 matched successfully.

Regarding mentorship, it is important to additionally note the specific impact of UIM mentors on UIM students. In a survey of UIM high school students following the completion of a health professional development program, Kendrick et al. demonstrated that racial/ethnic concordance between preceptor and student was significantly associated with viewing the preceptor as a role model (p = 0.028) [33]. Representation—across all levels of medical education, training, and institutional leadership—matters [34, 35]. National professional societies such as the Harry Barnes Medical Society and virtual platforms such as the Black Otolaryngologist Network have played a vital role for hosting opportunities for medical students and resident trainees to connect with fellow and senior faculty mentors in preparation for a successful career in OHNS. The Harry Barnes Medical Society was founded in 1989 by Black otolaryngologists of the National Medical Association to honor Dr. Barnes (the first board-certified Black otolaryngologist) and generations of UIM students and trainees in otolaryngology. The Black Otolaryngologist Network, a nonprofit organization founded in 2020, with the mission to promote mentorship, sponsorship, and the advancement of UIM students and trainees in the field. It is essential for non-minority-identifying professional societies to partner with minority-identifying platforms and societies to optimize outreach and maximize the opportunities available to UIM students.

Conclusions

Currently, the diversity of the surgical workforce does not reflect the diversity of the general patient population, and ultimately this continues to contribute to disparities in health equity. There is an urgent need to diversify the OHNS workforce to better meet patient needs and to impact generations of future otolaryngologists [36]. Although recent literature has focused on diversity in OHNS (Table 2), further work to understand the specific barriers faced by UIM students pursuing a career in OHNS is crucial. Through concerted, collaborative effort and unwavering commitment to develop formalized early pathways to OHNS for UIM students, significant progress can and will be made in addressing the diversity in the OHNS workforce.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •• Of major importance

Association of American Medical Colleges. Underrepresented in medicine definition. Accessed December 24, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/urm/.

Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in medicine: facts and figures. Published 2019. Accessed December 24, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-18-percentage-all-active-physicians-race/ethnicity-2018.

US Census Bureau. QuickFacts: United States. Accessed December 24, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-18-percentage-all-active-physicians-race/ethnicity-2018.

Eras statistics. AAMC. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/interactive-data/eras-statistics-data (Accessed: February 9, 2023).

Truesdale CM, Baugh RF, Brenner MJ, Loyo M, Megwalu UC, Moore CE, Paddock EA, Prince ME, Strange M, Sylvester MJ, Thompson DM, Valdez TA, Xie Y, Bradford CR, Taylor DJ. Prioritizing diversity in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery: starting a conversation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(2):229–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820960722. Epub 2020 Oct 13 PMID: 33045901.

Butler PD, Longaker MT, Britt LD. Major deficit in the number of underrepresented minority academic surgeons persists. Ann Surg. 2008;248(5):704–11.

Moy E, Bartman BA. Physician race and care of minority and medically indigent patients. JAMA. 1995;273(19):1515–20.

Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M, et al. The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(20):1305–10.

Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Veloski JJ, Gayle JA. The impact of multiple predictors on generalist physicians’ care of under- served populations. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1225–8.

Saha S, Taggart SH, Komaromy M, Bindman AB. Do patients choose physicians of their own race? Health Aff (Millwood). 2000;19(4):76–83.

Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, Bindman AB. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(9):997–1004.

Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(3):296–306.

Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(9):537–46.

Branson RD, Davis K Jr, Butler KL. African Americans’ participation in clinical research: importance, barriers, and solutions. Am J Surg. 2007;193(1):32–9.

Whitla DK, Orfield G, Silen W, Teperow C, Howard C, Reede J. Educational benefits of diversity in medical school: a survey of students. Acad Med. 2003;78(5):460–6.

•• Burks CA, Russell TI, Goss D, et al. Strategies to increase racial and ethnic diversity in the surgical workforce: a state of the art review. Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2022;166(6):1182–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998221094461. This state-of-the-art review highlights strategies to increase racial and ethnic diversity in the surgical workforce such as; Internship programs, required clerkships, diversifying recruitment and selection process for residency match and faculty hiring, increasing representation, holistic review processes, dedicated mentorship and departmental commitment.

Faucett EA, Newsome H, Chelius T, Francis CL, Thompson DM, Flanary VA. African American otolaryngologists: current trends and factors influencing career choice. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(10):2336–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.28420.

Johnson BC, Hayden J, Jackson J, Harley R, Harley EH Jr. Hurdles in diversifying otolaryngology: a survey of medical students. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;166(6):1161–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998221076835. Epub 2022 Feb 8 PMID: 35133915.

Barnum TJ, Salzman DH, Odell DD, et al. Orientation to the operating room: an introduction to the surgery clerkship for third-year medical students. MedEdPORTAL. Published online November 14, 2017:10652. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10652.

London DA, Calfee RP, Boyer MI. Impact of a musculoskeletal clerkship on orthopedic surgery applicant diversity. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2016;45(6):E347–51.

Bernstein J, DiCaprio MR, Mehta S. The relationship between required medical school instruction in musculoskeletal medicine and application rates to orthopaedic surgery residency programs: J Bone Jt Surg. 2004;86(10):2335–8. https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-200410000-00031.

Ramirez AV, Espinoza V, Ojeaga M, Garza A, Hensler B, Honrubia V. Home away from home: mentorship and research in private practices for students without home programs. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;168(3):546–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998221120231. Epub 2023 Jan 27 PMID: 36040813.

Mason BS, Ross W, Ortega G, Chambers MC, Parks ML. Can a strategic pipeline initiative increase the number of women and underrepresented minorities in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(9):1979–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-4846-8.

Landeen KC, Esianor B, Stevens MN, et al. Online otolaryngology: a comprehensive model for medical student engagement in the virtual era and beyond. Ear Nose Throat J. Published online July 5, 2021:014556132110297. https://doi.org/10.1177/01455613211029748.

•• Esianor BI, Kloosterman N, Cabrera-Muffly C, Brown DJ, Vinson KN. Critical components of diversity initiatives. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2021;54(3):665–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2021.02.007. This work emphasizes the critical components of diversity initiatives including Identifying stakeholders, team development, reflection on the past, analysis of the present, preparation for the future, and continuous quality improvement.

Ortega CA, Keah NM, Dorismond C, Peterson AA, Flanary VA, Brenner MJ, Esianor BI. Leveraging the virtual landscape to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion in otolaryngology-head & neck surgery. Am J Otolaryngol. 2023 Jan-Feb;44(1):103673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2022.103673. Epub 2022 Oct 20. PMID: 36302328.

Nellis JC, Eisele DW, Francis HW, Hillel AT, Lin SY. Impact of a mentored student clerkship on underrepresented minority diversity in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery: mentored OHNS clerkship for minority students. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(12):2684–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.25992.

McDonald TC, Drake LC, Replogle WH, Graves ML, Brooks JT. Barriers to increasing diversity in orthopaedics: the residency program perspective. JBJS Open Access. 2020;5(2):e0007–e0007. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.OA.20.00007.

Munjal T, Nathan CA, Brenner MJ, Stankovic KM, Francis HW, Valdez TA. Re-engineering the surgeon-scientist pipeline: advancing diversity and equity to fuel scientific innovation. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(10):2161–3. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29800. Epub 2021 Aug 12 PMID: 34383298.

•• Fang CH, Barinsky GL, Gray ST, Baredes S, Chandrasekhar SS, Eloy JA. Diversifying researchers and funding in otolaryngology. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2021;54(3):653–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2021.01.008. This study highlights the implications of disparities in research funding in OHNS and advocates for early research exposure and funding support for women and UIM.

Kaplan AB, Riedy KN, Grundfast KM. Increasing competitiveness for an otolaryngology residency: where we are and concerns about the future. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153(5):699–701. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599815593734. Epub 2015 Jul 17 PMID: 26187905.

Butler PD, Britt LD, Green ML, et al. The diverse surgeons initiative: an effective method for increasing the number of under-represented minorities in academic surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(4):561–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.06.019.

Kendrick K, Withey S, Batson A, Wright SM, O’Rourke P. Predictors of satisfying and impactful clinical shadowing experiences for underrepresented minority high school students interested in healthcare careers. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112(4):381–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2020.04.007.

Thompson-Harvey A, Drake M, Flanary VA. Perceptions of otolaryngology residency among students underrepresented in medicine. Laryngoscope. 2022;132(12):2335–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.30090. Epub 2022 Mar 4 PMID: 35244230.

Nguemeni Tiako MJ, Johnson S, Muhammad M, Osman NY, Solomon SR. Association between racial and ethnic diversity in medical specialties and residency application rates. JAMA Netw Open. 2022 Nov 1;5(11):e2240817. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.40817. PMID: 36367730; PMCID: PMC9652751.

Francis CL, Cabrera-Muffly C, Shuman AG, Brown DJ. The value of diversity, equity, and inclusion in otolaryngology. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2022;55(1):193–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2021.07.017. PMID: 34823717.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Regan W. Bergmark reports Nesson Fellow, Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Institutional faculty grant funding and salary support for research on disparities in timely access to high-quality surgical care); United Against Racism Subspeciality Grant, Mass General Brigham; Grant funding, I-Mab Biopharma. Ciersten A. Burks reports United Against Racism Subspeciality Grant, Mass General Brigham. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Taylor Brown and Symone Jordan share first authorship.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, T., Jordan, S., Watson, J. et al. Developing Early Pathways to Otolaryngology. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep 11, 193–200 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40136-023-00462-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40136-023-00462-5