Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review aims to examine the evidence and trends of ex utero intrapartum therapy (EXIT) and its various treatment modalities, with a focus on foetal survival outcomes.

Recent Findings

A review of the literature (2017–2022) revealed 126 reported cases. EXIT for the management of congenital diaphragmatic hernias is now infrequently performed due to alternative foetoscopic techniques. Airway management remains the main indication for EXIT. Overall mortality was 24% whilst the EXIT interventions themselves had low immediate ‘procedure-specific’ mortality (4%). This suggests that subsequent mortality is related to other perinatal factors. Recent developments also include use of 3D modelling for simulation and MDT training before embarking on the procedure.

Summary

EXIT is a controlled intervention for complex foetal airway pathology which has good outcomes with minimal morbidity. In the future, EXIT may continue to broaden its indications; therefore, more evidence and structured guidance should be adopted for reporting of intervention outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ex utero intrapartum therapy (EXIT) is a term that describes interventions on the foetus whilst still connected to utero-placental circulation. First described in the late twentieth century, EXIT strategies have matured over the last three decades, and are currently adopted worldwide to manage complex foetal airway conditions, which would otherwise be incompatible with life [1•, 2, 3, 4•]. For a successful outcome, accurate prenatal diagnostic workup, multidisciplinary team (MDT) collaboration and good communication are paramount [5••].

In this review, we aim to (1) introduce EXIT and its role; and (2) highlight the latest findings from the literature in the last 5 years.

The ‘EXIT’ Procedure

Early EXIT was termed operation on placental support (OOPS). Norris et al., in 1989, were the first to report OOPS for management of foetal upper airway obstruction. The foetus with a large anterior neck mass was partially delivered and maintained, for several minutes, on utero-placental circulation by delaying umbilical cord clamping [6]. In 1997, Mychaliska et al. were the first to coin the term ‘EXIT procedure’; they described a systematic approach for managing complex foetal airways. Their series of eight consisted of EXIT performed for two cases of head and neck lymphangioma and six cases of congenital diaphragmatic hernias (CDH) [7]. For the management of CDH, EXIT has been used for the reversal of foetoscopic endoluminal tracheal occlusion (FETO), where the foetal tracheal is plugged with a balloon or clip, to encourage lung maturation and improve pulmonary hypoplasia in severe cases of CDH [7, 8].

Initially, no attempts were made in order to prolong utero-placental circulation, which resulted in short procedure times, ranging 5–20 min, from start of caesarean section to cord clamping, and therefore higher foetal morbidity [6]. Since then, a better understanding and advances in maternal anaesthesia and pharmacological agents have enabled prolongation of the third phase of labour, with improved and sustained uterine relaxation, to maximise the utero-placental circulation time [9–13]. Although utero-placental circulation times of up to 150 min have been reported in literature, most studies reported times from 45 to 60 min, which is more relevant for EXIT planning [14–16].

In 2002, Bouchard and his team at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia published a landmark series of 31 EXIT cases. The most common indications in their paper for EXIT were foetal airway obstruction secondary to a head and neck mass, and reversal of FETO for CDH [17]. Other indications for EXIT also included congenital high airway obstruction syndrome (CHAOS), extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), unilateral pulmonary agenesis and delivery of conjoined twins. In the ECMO cases, their mean duration of utero-placental bypass was 30.3 min, and all infants were haemodynamically stable. Amongst their 31 cases, there was one death during EXIT from failure to establish a secure airway.

Another milestone in the literature, in 2004, is the case series from Hirose et al. on 52 patients who underwent EXIT [15]. As with the previous reports, the most common indication for the procedure was CDH. Seven patients underwent EXIT due to airway obstruction secondary to neck masses and CHAOS. Amongst them, five patients underwent tracheostomy, one patient was intubated, and another patient underwent resection of the causative mass whilst under utero-placental circulation.

Anaesthetic Considerations

The main anaesthetic challenge in the EXIT procedure is to achieve optimal uterine relaxation [11]. This reduces the risk of placental abruption and allows the continuation of utero-placental circulation.

Several maternal factors pose challenges for anaesthesia during the EXIT procedure. At the depth of anaesthesia required to achieve uterine relaxation, maternal hypotension may occur in the supine position and consequently utero-placental hypoperfusion [11, 18–21]. Also, changes in maternal respiratory physiology can cause decreased maternal functional residual capacity, which can result in maternal hypoxia [20, 21].

Foetal physiology also poses an additional challenge in anaesthesia. Foetal cardiovascular circulation may be negatively affected by inhaled anaesthetics during EXIT, giving rise to cardiac depression, vasodilation and ultimately hypoxia and acidosis [22, 23]. Furthermore, foetal skin is thin and sensitive to fluid evaporation, and this increases the susceptibility for hypovolaemia during the duration of intervention [19].

Despite the above difficulties, an inhalation-based technique has traditionally been considered the anaesthetic of choice for EXIT, for example desflurane, halothane and isoflurane in isolation or in combination [4•, 24]. These inhalation agents have a superior effect on uterine relaxation, rapid placental transfer and quick elimination, improving titration of anaesthesia [19]. Intravenous anaesthesia such as propofol and remifentanil has also been reported as alternatives to inhalation anaesthesia and has a dose-dependent effect on uterine muscle contraction [14]. Uterine relaxation is further achieved by administration of tocolytics, such as indomethacin and nitroglycerin [18].

Perioperative monitoring of the mother and foetus is vital during the EXIT procedure. Maternal arterial blood pressure, oxygen saturation and end-tidal carbon dioxide levels are continuously monitored to detect potential maternal hypotension and hypoperfusion. Similarly, foetal saturation is continuously monitored to identify any foetal hypoperfusion [4•]. Foetal echocardiogram is also used during the EXIT procedure to detect any signs of foetal bradycardia [25–27].

Obstetric Considerations

Obstetric techniques in EXIT depend on the indication and modality of intervention, as well as the position of the placenta and the foetus. As utero-placental circulation needs to be maintained, placental integrity needs to be protected during the hysterotomy stage of C-section. Planning the incision depends largely on the position of the placenta. For example, in cases where the placenta is anteriorly placed, a transverse laparotomy skin incision may be required, rather than the traditional low horizontal pfannenstiel incision [18]. Intraoperative ultrasound can be utilised to accurately identify the position and borders of the placenta, as well as the foetal head position to avoid unnecessary trauma and compromising the placenta during the hysterotomy incision [4•, 28]. Only the foetal head, neck and shoulders are delivered during the procedure whilst the umbilical cord remains within the uterus in order to prevent cord compression. Maintenance of uterine volume during partial delivery of the foetus is crucial and can be considered a form of controlled amnioreduction; this can be achieved by infusing warm Ringer’s solution through the hysterotomy site [4•, 29, 30].

Once EXIT is completed, after completion of delivery or the utero-placental circulation comes to an end, continued uterine relaxation increases the risk of maternal blood loss, following placental detachment. Therefore, it is vital to achieve prompt uterine contraction following delivery [18, 19]. Initiation of oxytocin is typically administered to initiate uterine contraction and the timing of this relies on good communication within the EXIT MDT members, particularly the obstetric and the anaesthetic teams [4•, 29, 30].

Otolaryngology Considerations

The role of otolaryngology in EXIT is to obtain surgical access of the airway, where intubation is not feasible or has been unsuccessful. Depending on the underlying pathology and the clinical condition, the otolaryngologist may need to perform airway interventions (i.e. direct or endoscopic intubation), surgical access (i.e. tracheostomy, excision or debulking lesions in the head and neck), and even palliation.

Prenatal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the primary imaging modalities used for diagnosis of foetal pathology, which may be performed serially depending on local resources [31–35]. Of interest to otolaryngology are the findings suggestive of a compromised or difficult airway access. These signs may present along a spectrum, such as degree of micrognathia, facial or skeletal anomalies, the location, nature and size of head and neck masses and severity of CHAOS [5••, 18, 36•, 37•]. The dynamic effect of pathology on the airway may only be appreciated ex-utero, therefore the otolaryngologist and the multidisciplinary team should prepared for and be familiar with different EXIT strategies in the event of intrapartum variations or complications [7, 18, 38].

Recent reports of EXIT, which will be discussed in more detail later in this paper, have introduced novel non-airway indications, where the neonatal airway remains safe and stable without tracheostomy [18, 39, 40, 41]. However, for majority of those delivered via EXIT, otolaryngology will have a continued role in care as part of the complex airway multidisciplinary team; for decisions on investigations, genetics, and subsequent airway procedures. The key disciplines in the complex airway multidisciplinary team are, but not limited to, otolaryngology, respiratory, neonatal and paediatric medicine. In practice, EXIT is the start of the surgeon-patient relationship for otolaryngologists, as foetal pathology that necessitates EXIT is likely to need further intervention and long-term surveillance if the patient survives beyond the neonatal period [5,42, 43, 44].

Recent Updates: the Last 5 Years of EXIT

Method

A literature review was undertaken from the PubMed/EMBASE and MEDLINE databases, to identify new publications on EXIT and CHAOS published in the last 5 years (2017–2022). Abstracts and full-text articles were screened to determine their relevance for inclusion. All publications that reported EXIT outcomes were included for analysis; non-English language articles without available English translations were excluded from this review. Publications where perinatal events ultimately did not lead to EXIT (e.g. foetal demise, elective termination of pregnancy), or where significant case-specific details were not available, were also excluded. Data was collated on the sample size, indication of EXIT, gestational age at delivery, modality of interventions, confirmed pathology and survival outcomes. For the purpose of this review, survival outcomes were analysed at the following time points: (1) immediate: at the end of the intervention or the end of delivery, (2) day 1: 24 h from delivery, (3) neonatal: 28 days and (4) infant: 1 year. The end of the EXIT intervention was defined as the point where separation of the foetus from utero-placental circulation occurred, and the intervention was deemed a success if the neonate was successfully transitioned from utero-placental circulation to an alternative support mechanism (i.e. intubation and ventilation, ECMO or tracheostomy).

Results

Forty-one publications met criteria for review, reporting 126 new cases of EXIT, of which only 114 had EXIT-specific data available and were included. The highest level of evidence for EXIT outcomes remained at level 4—case series.

The indications for EXIT were consistent with previous literature and in this cohort, the most common indications were EXIT for head and neck masses (n = 70, 61%), followed by CHAOS (n = 21, 30%). 23% were for other indications: mediastinal mass, CDH, congenital heart disease and giant omphalocele. Interestingly, there was only one case reporting EXIT for CDH (4%). Whilst most of these cases were for established indications of EXIT, Chen et al. were the first to report a series of seven patients who underwent EXIT for the management for giant omphalocele, which will be discussed in more detail later on in the paper [41•]. A further novel indication was reported by Zhuang et al., where EXIT enabled the immediate drainage of a severe pericardial effusion secondary to a cardiac haemangioma, which further broadens the utilisation of EXIT [45•].

Of the head and neck mass indications, the most common histopathological diagnoses was teratoma, followed by lymphatic malformation. Over half of the CHAOS cases were found to be due to laryngeal atresia, with the remaining cases being tracheal atresia, multilevel airway atresia and tracheal agenesis.

Intubation was the most common EXIT modality. Sixty-five cases (57%) were successfully intubated, 43 (38%) had tracheostomy, two were transitioned to ECMO, and one had reversal of FETO. Within the intubated cohort, 36 were intubated, with no further details of procedure specified, 10 achieved direct laryngoscopy and intubation, three reported the use of video or flexible endoscopes, 15 required rigid bronchoscopy, and 1 required retrograde intubation. The mean gestational age at delivery was 35 weeks (95% CI 34.2–35.8). In 3 cases, EXIT intervention was unsuccessful leading to demise. Table 1 summarises the key findings from our review of EXIT including a descriptive summary of EXIT modality and outcomes.

The last 5 years of EXIT modalities remained consistent with established interventions. The success of intubation may be attributed to the utilisation of adjuncts, such as video and flexible endoscopes, which provide better visualisation and navigation capabilities of the complex foetal airway [41•, 45•]. Although only three cases reported the use of intubation adjuncts, this may be an underestimate as 32% of cases did not have available details on the intubation procedure. Tracheostomy was required in 38% of cases.

Meta-analysis on Survival and Mortality

From past literature, survival and mortality rates for EXIT have not been clear, with perinatal mortality rates of 10–50% being reported and some papers preferring to discuss the theoretical risk instead [5••, 65, 72]. Therefore, it is not clear whether these reported outcomes represent ‘procedure specific mortality rate’, i.e. death due to the failure of the EXIT itself; ‘disease specific mortality rate’ due to the progression of primary pathology that necessitated EXIT to begin with; or ‘overall mortality rate’ that encompasses all aetiologies, including non-specific causes such as infection, preterm or cardiopulmonary complications. Unfortunately, there remains no consensus on minimum reporting standards or follow-up period for EXIT, resulting in a large variation in available information that makes a formal meta-analysis difficult.

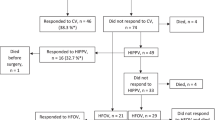

Of the cases included in the review, only 75 had sufficient case-specific details on foetal outcomes for meta-analysis. In this group, overall mortality was at 24%. Where case-specific details on survival outcomes, timing and modality of EXIT were available, data was constructed into a Kaplan Meier curve, for review of survival following EXIT (Fig. 1).

Our analysis showed that the vast majority of patients survive (95%, 71 out of 75 cases) immediately after EXIT. In three cases (4%), mortality was immediately after birth: two due to failure of airway management, and another due to massive tumour haemorrhage. All of the remaining patients survived for the first 24 h. Eight cases (11%) passed away in the neonatal period due to the following causes: neonatal sepsis; cerebral venous thrombosis; non-immune hydrops; coagulopathy; tumour lysis syndrome; palliation due to poor prognosis with aggressive tumour. Two more deaths were observed during infancy, at 5 and 18 months of age, as a result of tracheostomy accidents.

These results demonstrates that, at 4%, the procedure-specific mortality rate of EXIT is much lower than the often associated. Overall mortality for patients undergoing EXIT is largely related underlying pathology as a consequence of disease progression or complications of surgical procedures and interventions. Whilst this raises difficult clinical and ethical questions regarding when EXIT should be offered, more research is necessary for better prognostication of the foetal pathologies that necessitate EXIT.

Discussion

EXIT Update on Indications

With increased knowledge and technical abilities, the indications for EXIT have expanded. Broadly, they are EXIT for (1) reversal of tracheal occlusion; (2) the treatment of upper airway obstruction; (3) the treatment of chest and mediastinal masses; (4) ECMO; and (5) separation of conjoined twins. As previously mentioned, EXIT was originally designed for the reversal of tracheal occlusion at delivery for foetuses with severe CDH. This indication has been replaced largely by foetoscopic transabdominal puncture, to deflate the occluding tracheal balloon, reserving EXIT as a last resort [66]. This is supported by our review of recent literature which shows that upper airway obstruction, from head and neck masses and CHAOS, is the most common indication for EXIT.

Omphaloceles are herniation of peritoneal contents through a weakness in the abdominal wall and are often diagnosed on routine prenatal imaging. Surgical correction of omphalocele is dependent on the size of the herniation and is ideally done within the first few days of life [28]. The case series by Chen et al. was the first to report EXIT for the management of omphaloceles (n = 7) [41•]. Prenatally, there was no concern about a difficult airway or foetal distress. They proposed that prompt securing of the airway facilitates surgery soon after birth, by minimising air ingestion, reducing intra-abdominal pressures and minimising the need for multiple or staged procedures to obtain closure of the abdominal wall. However, further evidence is required to determine if EXIT provides additional benefit over traditional methods of post-partum omphalocele surgery.

Foetoscopic Interventions and EXIT

Foetoscopic laryngotomy has been described to relieve symptoms of foetal hydrops in cases of CHAOS and promote foetal cardiopulmonary development, rather than achieve adequate airway recannalisation, and it is known to be associated with increased risk of preterm labour [73, 74]. Nicolas et al. reported the first ultrasound-guided percutaneous aspiration of the foetal trachea instead of LASER laryngotomy [61•] and in our review, laser ablation remained the main foetoscopic airway procedure undertaken in the EXIT cohort. All patients who had foetoscopic airway interventions had preterm deliveries and tracheostomy as their EXIT modality, with 33% failure of EXIT to secure the airway (n = 2).

International Paediatric Otolaryngology Group (IPOG) Guidance

In 2020, the International Paediatric Otolaryngology Group (IPOG) published their recommendations on the management of airway obstruction in the pre- and perinatal period; it is the first published guidance to support EXIT procedure planning and decision-making. This consensus document, aimed at the surgeons and MDT members professionals, was derived from the expert opinion of IPOG members, predominantly otolaryngologists working in tertiary and quaternary referral centres across eight different countries [5••].

3D Modelling and Simulation for EXIT

Recent IPOG guidance has recommended that annual simulation should be undertaken by members of the EXIT MDT team [5••]. We highlight here the recent trends in simulation for EXIT.

Werner et al. had previously described how 3D printing can be applied from imaging data to create models of foetal anatomy [75•, 76, 77]. In particular, for EXIT planning and simulation, their work has demonstrated how complex airways can be assessed prenatally through virtual bronchoscopy [75•]. In recent literature, low-fidelity moulage-style scenarios have been brought back into focus, through case reports on how pre-procedure simulation facilitates the delivery of EXIT [49, 53, 78, 79•]. For example, King et al. describe how their table-top simulation of different intraoperative scenarios helped coordinate performance on the day, involving as many as 29 individuals in a single operating theatre [53].

There has also been more work published on patient-specific 3D modelling as a simulation adjunct and mode EXIT planning [80, 81]. VanKoevering et al. reported a case where 3D modelling from foetal MRI helped differentiate a protuberant bilateral cleft lip and palate, with a prominent premaxilla and philtrum segment, from a potentially obstructive facial lesion (e.g. lymphangioma, epignathus) [82•]. This case demonstrates and shows how 3D modelling contributed to airway management planning and led to the de-escalation of a potential EXIT procedure. For an otherwise in-utero patient, imaging-based 3D models present an opportunity for the surgeon and airway MDT members to perform an assessment of the airway akin to their regular practice.

Albeit novel, the literature on 3D modelling for use in EXIT MDT is limited and yet to be validated. In addition, existing imaging protocols may not be adequate for 3D modelling and new software or repeat imaging may be required, which will expend further time and resources. Therefore, uptake of simulation and its adjuncts will depend on local infrastructure and resources, and may be of limited application in late-presenting or emergency EXIT cases. Nevertheless, MDT simulation or a pre-procedure run-through for EXIT is generally recommended.

Conclusion

EXIT is utilised worldwide for complex foetal pathology and airway rescue. Recent developments include the IPOG consensus guidance on EXIT. Whilst largely indicated for EXIT is the management of foetal head and neck masses and CHAOS, there is potential for wider utilisation of EXIT. The benefit of prolonged utero-placental circulation has been reported to be beneficial for neonatal procedures immediately after birth, such as drainage of pericardial effusions and management of giant omphaloceles. Pre-EXIT simulation and MDT coordination remain vital for the delivery of EXIT and it is generally encouraged, to maintain good outcomes for such a high-stakes intervention. Further research and consensus on minimum reporting standards should be considered in future studies and publications to build on the current evidence-base. Nevertheless, our review has shown that EXIT can be delivered with minimal morbidity to mother and foetus.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Brodsky JR, Irace AL, Didas A, Watters K, Estroff JA, Barnewolt CE, et al. Teratoma of the neonatal head and neck: A 41-year experience. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;97:66–71 A large case series of 14 head and neck teratomas, published in the last five years, with survival outcomes and complications, of which four underwent EXIT successfully but had functional complications from teratoma excision.

Butler CR, Maughan EF, Pandya P, Hewitt R. Ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) for upper airway obstruction. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;25(2):119–26.

Crombleholme TM, Sylvester K, Flake AW, Adzick NS. Salvage of a fetus with congenital high airway obstruction syndrome by ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2000;15(5):280–2.

Spiers A, Legendre G, Biquard F, Descamps P, Corroenne R. Ex utero intrapartum technique (EXIT): Indications, procedure methods and materno-fetal complications - A literature review. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod, A recent review article on EXIT, within the last year, with a focus on obstetric considerations and maternal outcomes. 2022;51(1):102252.

Puricelli MD, Rahbar R, Allen GC, Balakrishnan K, Brigger MT, Daniel SJ, et al. International Pediatric Otolaryngology Group (IPOG): Consensus recommendations on the prenatal and perinatal management of anticipated airway obstruction. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;138:110281 The first publication on international consensus of EXIT for anticipated airway obstruction.

Norris MC, Joseph J, Leighton BL. Anesthesia for perinatal surgery. Am J Perinatol. 1989;6(1):39–40.

Mychaliska GB, Bealer JF, Graf JL, Rosen MA, Adzick NS, Harrison MR. Operating on placental support: the ex utero intrapartum treatment procedure. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32(2):227–30 discussion 230-231.

Deprest JA, Nicolaides KH, Benachi A, Gratacos E, Ryan G, Persico N, et al. Randomized trial of fetal surgery for severe left diaphragmatic hernia. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(2):107–18.

Catalano PJ, Urken ML, Alvarez M, Norton K, Wedgewood J, Holzman I, et al. New approach to the management of airway obstruction in ‘high risk’ neonates. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118(3):306–9.

Langer JC, Fitzgerald PG, Desa D, Filly RA, Golbus MS, Adzick NS, et al. Cervical cystic hygroma in the fetus: clinical spectrum and outcome. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25(1):58–61 discussion 61-62.

Schwartz DA, Moriarty KP, Tashjian DB, Wool RS, Parker RK, Markenson GR, et al. Anesthetic management of the exit (ex utero intrapartum treatment) procedure. J Clin Anesth. 2001;13(5):387–91.

Gaiser RR, Cheek TG, Kurth CD. Anesthetic management of cesarean delivery complicated by ex utero intrapartum treatment of the fetus. Anesth Analg. 1997;84(5):1150–3.

Skarsgard ED, Chitkara U, Krane EJ, Riley ET, Halamek LP, Dedo HH. The OOPS procedure (Operation on Placental Support): In utero airway management of the fetus with prenatally diagnosed tracheal obstruction. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31(6):826–8.

Osborn AJ, Baud D, Macarthur AJ, Propst EJ, Forte V, Blaser SM, et al. Multidisciplinary perinatal management of the compromised airway on placental support: lessons learned. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33(11):1080–7.

Hirose S, Farmer DL, Lee H, Nobuhara KK, Harrison MR. The ex utero intrapartum treatment procedure: Looking back at the EXIT. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39(3):375–80 discussion 375-380.

Hirose S, Sydorak RM, Tsao K, Cauldwell CB, Newman KD, Mychaliska GB, et al. Spectrum of intrapartum management strategies for giant fetal cervical teratoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(3):446–50 discussion 446-450.

Bouchard S, Johnson MP, Flake AW, Howell LJ, Myers LB, Adzick NS, et al. The EXIT procedure: experience and outcome in 31 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37(3):418–26.

Marwan A, Crombleholme TM. The EXIT procedure: principles, pitfalls, and progress. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2006;15(2):107–15.

Ngamprasertwong P, Vinks AA, Boat A. Update in fetal anesthesia for the ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2012;50(4):26–40.

Wood CL, Zuk J, Rollins MD, Silveira LJ, Feiner JR, Zaretsky M, et al. Anesthesia for Maternal-Fetal Interventions: A Survey of Fetal Therapy Centers in the North American Fetal Therapy Network. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2021;48(5):361–71.

Subramanian R, Mishra P, Subramaniam R, Bansal S. Role of anesthesiologist in ex utero intrapartum treatment procedure: A case and review of anesthetic management. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2018 Jun;34(2):148–54.

Holcberg G, Sapir O, Huleihel M, Katz M, Bashiri A, Mazor M, et al. Indomethacin activity in the fetal vasculature of normal and meconium exposed human placentae. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;94(2):230–3.

Palahniuk RJ, Shnider SM. Maternal and fetal cardiovascular and acid-base changes during halothane and isoflurane anesthesia in the pregnant ewe. Anesthesiology. 1974;41(5):462–72.

Turner RJ, Lambrost M, Holmes C, Katz SG, Downs CS, Collins DW, et al. The effects of sevoflurane on isolated gravid human myometrium. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2002;30(5):591–6.

Beckmann N, Luttrell J, Petty B, Rhodes C, Thompson J. Injection bronchoplasty with carboxymethlycellulose with cystoscopy needle for neonatal persistent bronchopleural fistulae. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;127:109651.

Kornacki J, Szydłowski J, Skrzypczak J, Szczepańska M, Rajewski M, Koziołek A, et al. Use of ex utero intrapartum treatment procedure in fetal neck and high airway anomalies - report of four clinical cases. J Matern-Fetal Neonatal Med Off J Eur Assoc Perinat Med Fed Asia Ocean Perinat Soc Int Soc Perinat Obstet. 2019;32(5):870–4 A recent case series of EXIT, within the last three years, where one out of four cases was unsuccessful in securing the airway.

Kumar M, Gupta A, Kumar V, Handa A, Balliyan M, Meena J, et al. Management of CHAOS by intact cord resuscitation: case report and literature review. J Matern-Fetal Neonatal Med Off J Eur Assoc Perinat Med Fed Asia Ocean Perinat Soc Int Soc Perinat Obstet. 2019;32(24):4181–7 The only publication within the last five years where EXIT to tracheostomy was performed in conjunction with a vaginal delivery, as the mother did not consent to C-section.

Erfani H, Nassr AA, Espinoza J, Lee TC, Shamshirsaz AA. A novel approach to ex-utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) in a case with complete anterior placenta. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;228:335–6.

Garcia PJ, Olutoye OO, Ivey RT, Olutoye OA. Case scenario: anesthesia for maternal-fetal surgery: the Ex Utero Intrapartum Therapy (EXIT) procedure. Anesthesiology. 2011;114(6):1446–52.

Butwick A, Aleshi P, Yamout I. Obstetric hemorrhage during an EXIT procedure for severe fetal airway obstruction. Can J Anaesth J Can Anesth. 2009;56(6):437–42.

Bonasoni MP, Comitini G, Barbieri V, Palicelli A, Salfi N, Pilu G. Fetal presentation of mediastinal immature teratoma: Ultrasound, autopsy and cytogenetic findings. Diagn Basel Switz. 2021;11(9):1543.

Recio Rodríguez M, Martínez de Vega V, Cano Alonso R, Carrascoso Arranz J, Martínez Ten P, Pérez Pedregosa J. MR imaging of thoracic abnormalities in the fetus. Radiogr Rev Publ Radiol Soc N Am Inc. 2012 Dec;32(7):E305–21.

Houshmand G, Hosseinzadeh K, Ozolek J. Prenatal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of a foregut duplication cyst of the tongue: value of real-time MRI evaluation of the fetal swallowing mechanism. J Ultrasound Med Off J Am Inst Ultrasound Med. 2011;30(6):843–50.

Myers LB, Bulich LA, Mizrahi A, Barnewolt C, Estroff J, Benson C, et al. Ultrasonographic guidance for location of the trachea during the EXIT procedure for cervical teratoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(4):E12.

Kathary N, Bulas DI, Newman KD, Schonberg RL. MRI imaging of fetal neck masses with airway compromise: utility in delivery planning. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31(10):727–31.

Bouwman FCM, Klein WM, de Blaauw I, Woiski MD, Verhoeven BH, Botden SMBI. Lymphatic malformations adjacent to the airway in neonates: Risk factors for outcome. J Pediatr Surg. 2021;56(10):1764–70 First study to report the following risk factors for poorer sclerotherapy outcomes in neonates with lymphovascular malformations; 1) prolonged hospital stay and 2) the need for treatment of the malformation in the neonatal period.

García-Díaz L, Chimenea A, de Agustín JC, Pavón A, Antiñolo G. Ex-Utero Intrapartum Treatment (EXIT): indications and outcome in fetal cervical and oropharyngeal masses. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):598 Recent publication on successful EXIT performed, within the last three years, with the utilisation of flexible endoscopy to secure the airway, in three of their series of five cases, avoiding the need for tracheostomy.

Perri A, Patti ML, Sbordone A, Vento G, Luciano R. Unexpected tracheal agenesis with prenatal diagnosis of aortic coarctation, lung hyperecogenicity and polyhydramnios: a case report. Ital J Pediatr. 2020;46(1):96.

Jani JC, Nicolaides KH, Gratacós E, Valencia CM, Doné E, Martinez JM, et al. Severe diaphragmatic hernia treated by fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol Off J Int Soc Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34(3):304–10.

Belfort MA, Olutoye OO, Cass DL, Olutoye OA, Cassady CI, Mehollin-Ray AR, et al. Feasibility and outcomes of fetoscopic tracheal occlusion for severe left diaphragmatic hernia. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(1):20–9.

Chen XY, Yang JX, Zhang HY, Xiong XF, Abdullahi KM, Wu XJ, et al. Ex utero intrapartum treatment for giant congenital omphalocele. World J Pediatr WJP. 2018;14(4):399–403 The first published case series of EXIT for the perinatal management of giant omphaloceles.

Morales CZ, Barrette LX, Vu GH, Kalmar CL, Oliver E, Gebb J, et al. Postnatal outcomes and risk factor analysis for patients with prenatally diagnosed oropharyngeal masses. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;152:110982 The second largest EXIT case series reported in the last five years, 14 cases, within a cohort of 62 prenatally diagnosed oropharyngeal masses.

Laje P, Peranteau WH, Hedrick HL, Flake AW, Johnson MP, Moldenhauer JS, et al. Ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) in the management of cervical lymphatic malformation. J Pediatr Surg. 2015 Feb;50(2):311–4.

Kornacki J, Skrzypczak J. Fetal neck tumors - antenatal and intrapartum management. Ginekol Pol. 2017;88(5):266–9.

Zhuang J, Pan W, Zhou CB, Han FZ. Ex utero intrapartum treatment for the pericardial effusion drain of a fetal cardiac tumor. Chin Med J (Engl). 2017;130(11):1381–2 The first reported case of EXIT utilised to facilitate pericardial drainage of effusion secondary to a cardiac tumour.

Yan C, Shentu W, Gu C, Cao Y, Chen Y, Li X, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of fetal oral masses by ultrasound combined with magnetic resonance imaging. J Ultrasound Med Off J Am Inst Ultrasound Med. 2022;41(3):597–604.

Barrette LX, Morales CZ, Oliver ER, Gebb JS, Feygin T, Lioy J, et al. Risk factor analysis and outcomes of airway management in antenatally diagnosed cervical masses. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;149:110851 The largest EXIT case series reported in the last five years, 15 cases, within a cohort of 52 antenatally diagnosed cervical masses.

Jeong SH, Lee MY, Kang OJ, Kim R, Chung JH, Won HS, et al. Perinatal outcome of fetuses with congenital high airway obstruction syndrome: a single-center experience. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2021;64(1):52–61 The largest case series of CHOAS reported in the last five years, with a total of 5 cases.

Sangaletti M, Garzon S, Raffaelli R, D’Alessandro R, Bosco M, Casarin J, et al. The Ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure: case report of a multidisciplinary team approach. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parm. 2021;92(S1):e2021142.

Shamshirsaz AA, Aalipour S, Stewart KA, Nassr AA, Furtun BY, Erfani H, et al. Perinatal characteristics and early childhood follow up after ex-utero intrapartum treatment for head and neck teratomas by prenatal diagnosis. Prenat Diagn. 2021;41(4):497–504 A large case series of EXIT for head and neck teratoma reported within the last five years, with a total of 11 cases.

Sirianni J, Abro J, Gutman D. Delivery of an infant with airway compression due to cystic hygroma at 37 weeks’ gestation requiring a multidisciplinary decision to use a combination of Ex Utero Intrapartum Treatment (EXIT) and Airway Palliation at Cesarean Section. Am J Case Rep. 2021;3(22):e927803.

Zaretsky M, Brockel M, Derderian SC, Francom C, Wood C. A Graceful EXIT impeded by obstetrical complications. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(2):e237911.

King A, Keswani SG, Belfort MA, Nassr AA, Shamshirsaz AA, Espinoza J, et al. EXIT (ex utero Intrapartum Treatment) to airway procedure for twin fetuses with oropharyngeal teratomas: lessons learned. Front Surg. 2020;7:598121.

Lee N, Bae MH, Han YM, Park KH, Hwang JY, Hwang CS, et al. Extracerebral choroid plexus papilloma in the pharynx with airway obstruction in a newborn: a case report. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20(1):336.

Lo RH, Mohd NKN, Abdullah K, Aziz A, Mohamad I. Ex Utero Intrapartum Treatment (Exit) of gigantic intrapartum lymphangioma and its management dilemma - a case report. Medeni Med J. 2020;35(2):161–5.

Peiro JL, Nolan HR, Alhajjat A, Diaz R, Gil-Guevara E, Tabbah SM, et al. A technical look at fetoscopic laser ablation for fetal laryngeal surgical recanalization in congenital high airway obstruction syndrome. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2020;30(6):695–700.

Reeve NH, Kahane JB, Spinner AG, O-Lee TJ. Ex utero intrapartum treatment to extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: lifesaving management of a giant cervical teratoma. J Laryngol Otol. 2020;134(7):650–3.

Arteaga A, Marroquín M, Guevara J. Intubation using C-MAC video laryngoscope during ex utero intrapartum treatment featuring upper airway neck mass: a case report. AA Pract. 2019;13(5):159–61.

Nolan HR, Gurria J, Peiro JL, Tabbah S, Diaz-Primera R, Polzin W, et al. Congenital high airway obstruction syndrome (CHAOS): Natural history, prenatal management strategies, and outcomes at a single comprehensive fetal center. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54(6):1153–8 A recent case series of EXIT, within the last three years, where all three cases of CHOAS were successfully delivered with tracheostomy.

Hochwald O, Gil Z, Gordin A, Winer Z, Avrahami R, Abargel E, et al. Three-step management of a newborn with a giant, highly vascularized, cervical teratoma: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2019;13(1):73.

Nicolas CT, Lynch-Salamon D, Bendel-Stenzel E, Tibesar R, Luks F, Eyerly-Webb S, et al. Fetoscopy-assisted percutaneous decompression of the distal trachea and lungs reverses hydrops fetalis and fetal distress in a fetus with laryngeal atresia. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2019;46(1):75–80 First reported case of percutaneous decompression of the trachea in a foetoscopic intervention for a case of CHAOS.

Masahata K, Soh H, Tachibana K, Sasahara J, Hirose M, Yamanishi T, et al. Clinical outcomes of ex utero intrapartum treatment for fetal airway obstruction. Pediatr Surg Int. 2019;35(8):835–43. A recent case series of nine EXIT cases for head and neck masses and CHAOS, where one was unsuccessful.

Asai H, Tachibana T, Shingu Y, Matsui Y. Ex utero intrapartum treatment-to-extracorporeal membrane oxygenation followed by cardiac operation for truncus arteriosus communis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2018;26(2):353–4.

Beck MM, Rai E, Vijayaselvi R, John M, Picardo N, Santhanam S, et al. Ex Utero Intrapartum Treatment (EXIT) for a large fetal neck mass. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2018;68(2):142–4.

Gonzales SK, Goudy S, Prickett K, Ellis J. EXIT (ex utero intrapartum treatment) in a growth restricted fetus with tracheal atresia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;105:72–4.

Lee J, Lee MY, Kim Y, Shim JY, Won HS, Jeong E, et al. Ex utero intrapartum treatment procedure in two fetuses with airway obstruction. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2018;61(3):417–20.

Olivares E, Castellow J, Khan J, Grasso S, Fong V. Massive fetal cervical teratoma managed with the ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure. Radiol Case Rep. 2018;13(2):389–91.

Tergestina M, Ross BJ, Manipadam MT, Kumar M. Malignant rhabdoid tumour of the neck in a neonate. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr-2017-223145.

Dharmarajan H, Rouillard-Bazinet N, Chandy BM. Mature and immature pediatric head and neck teratomas: A 15-year review at a large tertiary center. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;105:43–7 A large case series of EXIT, published in the last three years, reporting on 11 cases of which all were successful.

Yu YR, Espinoza J, Mehta DK, Keswani SG, Lee TC. Perinatal diagnosis and management of oropharyngeal fetus in fetu: A case report. J Clin Ultrasound JCU. 2018;46(4):286–91.

Wannemuehler TJ, Deig CR, Brown BP, Morgenstein SA. Obstructing in utero oropharyngeal mass: Case report of a lymphatic malformation arising within an oropharyngeal teratoma. Ear Nose Throat J. 2017;96(1):E37–40.

Kumar K, Miron C, Singh SI. Maternal anesthesia for EXIT procedure: A systematic review of literature. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2019;35(1):19–24.

Dick JR, Wimalasundera R, Nandi R. Maternal and fetal anaesthesia for fetal surgery. Anaesthesia. 2021;76(Suppl 4):63–8.

King A, Bedwell JR, Mehta DK, Stapleton GE, Justino H, Sutton C, et al. Fetoscopic balloon dilation and stent placement of congenital high airway obstruction syndrome leading to successful Caesarian delivery. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2022 Jan 7.

Werner H, Lopes dos Santos JR, Fontes R, Belmonte S, Daltro P, Gasparetto E, et al. Virtual bronchoscopy for evaluating cervical tumors of the fetus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41(1):90–4 A recent publication, within the last 3 years, where a case of EXIT for CHAOS failed to achieve airway access, despite use of virtual navigation technology such as 3D bronchoscope.

Werner H, Rolo LC, Araujo Júnior E, Dos Santos JRL. Manufacturing models of fetal malformations built from 3-dimensional ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, and computed tomography scan data. Ultrasound Q. 2014;30(1):69–75.

Werner H, Lopes J, Tonni G, Araujo JE. Physical model from 3D ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging scan data reconstruction of lumbosacral myelomeningocele in a fetus with Chiari II malformation. Childs Nerv Syst ChNS Off J Int Soc Pediatr Neurosurg. 2015;31(4):511–3.

Auguste TC, Boswick JA, Loyd MK, Battista A. The simulation of an ex utero intrapartum procedure to extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46(2):395–8.

Varela MF, Pinzon-Guzman C, Riddle S, Parikh R, McKinney D, Rutter M, et al. EXIT-to-airway: Fundamentals, prenatal work-up, and technical aspects. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2021;30(3):151066. Recent publication on EXIT with a focus on procedural considerations and coordination of the EXIT multidisciplinary team.

Pratt R, Deprest J, Vercauteren T, Ourselin S, David AL. Computer-assisted surgical planning and intraoperative guidance in fetal surgery: a systematic review. Prenat Diagn. 2015;35(12):1159–66.

Werner Júnior H, dos Santos JL, Belmonte S, Ribeiro G, Daltro P, Gasparetto EL, et al. Applicability of three-dimensional imaging techniques in fetal medicine. Radiol Bras. 2016;49(5):281–7.

VanKoevering KK, Morrison RJ, Prabhu SP, Torres MFL, Mychaliska GB, Treadwell MC, et al. Antenatal three-dimensional printing of aberrant facial anatomy. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1382–5 First case to report three-dimensional printing of fetal anatomy for EXIT planning which led to the decision to de-escalate the need for EXIT. The patient was diagnosed with a protuberant bilateral cleft lip rather than a head and neck mass.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical collection on PEDIATRIC OTOLARYNGOLOGY: Challenges in Pediatric Otolaryngology

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Goh, S., Peled, C. & Kuo, M. A Review of EXIT: Interventions for Neonatal Airway Rescue. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep 11, 27–36 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40136-023-00442-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40136-023-00442-9