Abstract

Purpose of Review

A trend of attributing abnormal voice changes to reflux has gained momentum among medical professionals over the last few decades. Evidence supporting the connection between reflux and voice and the use of anti-reflux medication in patients with dysphonia is conflicting and deserves careful examination. In the current health care environment, it is important that medical decisions be based on science rather than anecdote and practice patterns. The goal of this review is to investigate the evidence linking reflux and voice changes. Specifically, this association will be examined in the context of the Bradford Hill criteria to determine what evidence exists for a causal relationship between this exposure (reflux) and outcome (voice change).

Summary

Using the Bradford Hill criteria as a rubric, the evidence toward causality between reflux and voice is insufficient. The most compelling data derived from animal studies show biological plausibility, since an acidic environment does induce mucosal changes. However, evidence from human studies is largely associative. To date, neither clinical trials nor comparative observational studies have been able to demonstrate a strong dose–response relationship between reflux and voice disorders, temporality (reflux precedes dysphonia), consistent treatment effects, or strength of association between anti-reflux treatment and improved voice among patients with presumed laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR). Nonetheless, a relationship does exist between LPR and voice and it deserves careful consideration. However, the strength and nature of that association remain unclear.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The relationship between reflux and voice disorders has been in evolution over the last 40 years. It is increasingly common for physicians from multiple specialties to attribute voice changes to reflux particularly in the absence of other obvious etiologies. Patients presenting with voice complaints are often unaware that reflux could underlie their symptoms especially those that never experienced heartburn or regurgitation. Success of empiric treatment for reflux-attributed voice changes is variable. Despite decades of research, a method to consistently identify patients that will benefit from anti-reflux treatment for an isolated voice disorder remains elusive.

To investigate why this methodology remains indefinable, it is important to understand the distinction between association and causation. An association is a demonstrable relationship between two or more variables that renders them statistically dependent. Causation means that the one variable (exposure) is responsible for the occurrence of another (effect). It is unclear whether the association between reflux and voice is causal. Association alone is insufficient to establish causality. It is incumbent on clinicians and researchers not to overlook this central tenet of science, particularly when considering such relationships. Associations can be corroborated, but not definitively verified [1]. To address this limitation, the scientific community has developed criteria to provide evidence toward a causal relationship. An example is the Bradford Hill criteria as listed in Table 1 [2]. The present review investigates the relationship between reflux and voice within the context of these criteria.

Biologic Plausibility and Experimental Findings

Hypotheses regarding relationships are first developed based on some theoretical connection between the exposure and outcome. In the case of reflux and voice, this connection is primarily based on the proximity of the larynx to the upper esophageal inlet. Noxious refluxate (e.g., acid, pepsin and bile) from the stomach and duodenum enters the upper airway via the esophagus as laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) contacting the laryngopharyngeal mucosa leading to tissue damage. This type of reflux is physiologic when occurring intermittently and after meals. It only becomes pathologic if it occurs with adequate frequency or volume to result in symptoms or disease [3].

There is little question that reflux reaches the laryngopharynx. Pepsin, a marker of refluxate, has been identified in the mucosa of the upper airway and even the middle ear [4, 5]. Its proenzyme pepsinogen originates in the gastric chief cells, which cleaves to the digestive proteolytic enzyme pepsin at pH <2. Retained pepsin in the laryngopharyngeal mucosa is hypothesized to lead to LPR symptoms. Several proposed mechanisms have been advanced to explain how pepsin may damage laryngeal mucosa [4, 6, 7]. While its presence clearly demonstrates that reflux does reach the upper airway, wide agreement on the clinical consequence of pepsin in the larynx has not been established.

Another proposed mechanism of LPR pathophysiology involves imbalance of enzymes produced in the laryngopharyngeal mucosa. Carbonic anhydrase is an example of an intrinsic protective enzyme that converts hydrogen ions and carbon dioxide to bicarbonate and acts to buffer damage from acidic reflux. In biopsy specimens of LPR patients, carbonic anhydrase isoenzyme III was found to be absent in 64 %, whereas it was expressed in high levels in normal mucosa [8, 9]. Others have found laryngeal mucosa to have intrinsic H/K ATPase that is homologous to gastric H/K ATPase and is responsive to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy [10, 11]. Although interesting, a recent prospective study could only sporadically identify H/K ATPase in biopsies from patients with LPR diagnosed by pH/impedance studies [12]. Significant speculation still exists as to the mechanism of LPR-related damage.

Laboratory studies linking reflux to voice changes are difficult to perform and interpret. Animal models are used to study the effect of an acidic environment on the larynx, but their utility is limited for assessing voice changes. It is, however, possible to expose the larynx to noxious substances produced in the stomach and duodenum. Examples include exposure of high acid concentrations to canine larynges, which can cause vocal process granulomas and mucosal erythema [13, 14]. Experiments show that both pepsin and acid exposure to the larynx lead to significant histologic mucosal changes. Based on these studies and clinical experience, laryngeal histological changes are associated with voice changes, thereby supporting the assertion that reflux can cause voice changes.

Verdict: The relationship between reflux and dysphonia is biologically plausible based on anatomic and physiological considerations and basic science studies.

Dose–Response Relationship

The next causality criterion is whether a dose–response relationship is present between reflux and voice. Patients with more severe reflux should have worse symptoms. Several potential dose–response relationships would provide evidence toward causality including (1) that reflux in affected patients is detectable in the distal and proximal esophagus, (2) more frequent and/or higher volume reflux is associated with more symptoms and damage, and (3) a more acidic environment in the laryngopharynx is more injurious to mucosa.

What is the evidence that reflux is detectable in both the distal and proximal esophagus in LPR patients? Reflux necessarily derives from the stomach and duodenum. It is expected that patients with LPR would have measurable reflux across the entire esophagus since it ultimately reaches and damages the laryngopharynx. The gold standard test for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is 24–48-h intraluminal pH/impedance monitoring. Concerns about sensitivity of a single pH/impedance probe for detecting proximal esophageal reflux spurned the addition of a proximal esophageal or pharyngeal probe. Conceptually, the second probe should be more sensitive to detection of LPR events. However, the sensitivity of the proximal probe is poor and site-dependent, with an estimated 40 % sensitivity at the hypopharynx and 55 % sensitivity at the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) [15].

What is the evidence that more frequent and/or higher volume reflux is associated with more symptoms and injury? In a meta-analysis of dual probe studies, pH probe findings at or below the UES did not correlate with LPR symptoms (e.g., globus, throat clearing, cough, and voice change) [16]. However, these data depend on the type of LPR symptoms considered. In a prospective study of patients undergoing a dual pH monitoring with the upper probe in the hypopharynx 1 cm from the UES, findings did not correlate to the severity of LPR symptoms and events detected only significantly correlated to the symptom of heartburn [17]. In this study, the symptom of “hoarseness” was not significantly different between patients with LPR symptoms that had positive and negative pH probe studies. One could argue that the pH probe study is not sensitive enough to detect LPR leading to hoarseness between these two groups, or that voice change has an alternative explanation.

Is there evidence that a more acidic environment in the laryngopharynx is more injurious to mucosa? Adhami et al. investigated this relationship in a canine study in which standardized injury was induced in specific laryngeal subsites [13]. Each was exposed to pepsin, conjugated bile acids, unconjugated bile acids, and trypsin at graduated pH levels three times per week for a total of 9–12 applications. It showed that pepsin ± conjugated bile acids at pH 1–2 resulted in significant and severe histological inflammation and mucosal erythema compared to other agents. Minimal to no mucosal damage was induced at higher pH values. Vocal folds were the most sensitive to injury by applied solutions. A dose–response relationship is apparent. Lower pH does indeed result in histologic damage and clinical erythema. However, there appears to be a threshold pH (4) above which the risk of mucosal damage is diminished. Human study correlates are needed to confirm findings.

Verdict: Evidence exists for a dose–response between reflux and laryngeal damage in animal models, but a direct link in humans has yet to be established.

Temporality

An important criterion for causality is temporality (i.e., exposure precedes outcome). In the current context, reflux must preexist the voice disorder (dysphonia). Establishing this temporality is difficult. How is it possible to know if LPR was present prior to voice change if the patient had antecedent reflux-attributable symptoms or diagnostic test showing reflux prior to developing dysphonia? Often voice symptoms have been present over a month before presenting to an otolaryngologist and upon arrival most have trialed PPI therapy [18••]. To accurately establish temporality, a large prospective longitudinal population study in which nondysphonic patients with negative LPR symptoms and testing were followed with serial dual probe pH studies and laryngeal evaluations. Over time, it could be determined whether episodes of dysphonia were preceded by LPR exposures. Such a study would require a large study sample to be adequately powered. A simpler study would prospectively follow patients with and without evidence of pH/impedance confirmed GERD to determine whether differential hoarseness incidence developed between groups. Unfortunately, many argue that LPR and GERD are discrete conditions, since GERD symptoms are reported in only 40 % of LPR cases [19]. Thus, findings from a GERD cohort may not be representative of LPR patients.

Given the impracticality of large population-based trials, some information on temporality can be gleaned from emerging diagnostic tools. One example is mucosal impedance, which is designed to measure chronicity of mucosal disease [20•]. It detects changes in the esophageal mucosa exposed to recurrent reflux. In contrast to the tight intra-epithelial junctions of healthy esophageal mucosa, intra-epithelial junctions and cell membranes within reflux-exposed mucosa break down. Mucosal impedance testing capitalizes on these differences. Intact, nonpermeable epithelial junctions have higher impedance, while damaged, permeable epithelium has lower mucosal impedance. A prospective longitudinal study tested this hypothesis on 61 patients and found mucosal impedance to have a high sensitivity (95 %) and positive predictive value (96 %) for GERD-related esophagitis [20•]. As these diagnostic techniques are refined, they may better delineate whether upper esophageal and pharyngeal mucosa is chronically exposed to reflux and provide a window into how reflux chronicity contributes to dysphonia. However, even this technology cannot fully establish temporality, since changes in mucosal impedance do not directly correlate to a set time that mucosal damage occurred in relation to the clinical manifestation.

Verdict: Available studies do not clearly show a temporal relationship (exposure preexisting outcome) between reflux and onset of dysphonia.

Strength of Association

Strength of association refers to how strongly the presence or absence of a property is correlated with the presence or absence of another property. Statistically, this concept is measured by the relative risk or odds ratio (OR) of an effect or symptom arising from a population exposed to the presumed causative agent. In this case, evidence of a link between LPR and dysphonia would be higher odds of dysphonia among affected patients compared to those without LPR. It is important to recognize that testing this concept requires inclusion of a control group without the condition (i.e., LPR). In comparative studies, smaller effect sizes (i.e., OR closer to 1.0; no effect) are more likely to be explained by confounding and provide less evidence for a causal link between the exposure (reflux) and the outcome (voice).

Ideally, ecological studies comparing the risk of developing voice change in patients with and without reflux would be used to estimate its effect; however, no such studies have been performed. In reviewing the literature, relevant studies assessing OR of dysphonia with reflux were placebo-controlled trials. Most compared voice changes in LPR patients treated with anti-reflux medication versus placebo. In all, there have been eight placebo-controlled trials of PPI [21–28], one that compared PPI and lifestyle modification [29], and one comparing PPI alone versus combined PPI and voice therapy [30••]. Laryngopharyngeal reflux cases were identified using symptoms or laryngoscopic findings alone in three studies [22, 27, 29], while the remainder used objective testing (i.e., pH probe). Voice outcomes were assessed by a variety of methods: RSI [27, 30••], nonvalidated voice symptom scores or diaries [22–26, 28, 29], and a validated, LPR quality of life survey [21]. For five studies identified [22, 23, 25, 26, 28], the effect size (i.e., OR) for the association between reflux and dysphonia (when present) or composite laryngeal symptom resolution was calculated using 2 × 2 tables. For the remaining studies [21, 24, 27, 29, 30••], odds ratio was calculated using the Cox Logit method based on the standardized mean difference and variance calculated from the summary data provided in the manuscripts [31].

Proton Pump Inhibitors

Of eight placebo-controlled trials, two reported a significant improvement in voice outcomes with twice-daily PPIs (Fig. 1; Table 2) [23, 27]. Specifically, they found five- and ninefold increased odds of voice improvement among those treated with PPI based on change in the RSI and a symptom questionnaire for GERD/laryngitis, respectively. Both assessed voice outcomes 12 weeks post-treatment; however, assessment of exposure status differed. Reichel et al. used the RSI and RFS without pH study confirmation to define LPR exposure [27]. El-Serag et al. defined the study population by symptoms, laryngoscopy, esophagoscopy, and pH monitoring [23]. A third trial by Noordzij et al. that evaluated twice-daily PPI and objectively measured reflux via pH probe [24]. Using change in symptom score, it found that patients with a lower initial hoarseness score had more improvement than the placebo group, but that this change was not present with increasingly severe hoarseness. Unfortunately, this study’s results may be biased by ineffective randomization, as baseline hoarseness symptom severity significantly differed between groups. Furthermore, PPIs showed no effect on dysphonia when the odds ratio was estimated using the standardized mean difference from the hoarseness symptom scores reported in the manuscript.

Speech Therapy

Another randomized controlled trial from Park et al. compared PPI alone to PPI + voice therapy for patients diagnosed with LPR based on RSI and RFS findings [30••]. They found that LPR patients treated with combined therapy had significant improvement compared to PPI alone (Fig. 1; Table 2). These results were interpreted by the authors as indicating that speech therapy is an adjunct to PPI for treatment of affected individuals. However, because there was no group that received speech therapy alone, an alternate explanation for the results is that speech therapy helps patients with signs and symptoms historically been attributed to LPR, who may instead have muscle tension dysphonia.

Verdict: Current evidence suggests, at best, a weak association between PPI treatment and voice improvement in patients with symptoms attributed to LPR.

Consistency

Consistency in establishing causality refers to agreement in findings between similarly conducted studies. The preponderance of studies reviewed in Strength of Association failed to show association between reflux and voice. Inconsistency of these studies could be construed as lack of evidence of effectiveness. However, other possible explanations deserve consideration. In particular, results could be biased and confounded by heterogeneity in the measurement/assessment of both the exposure (LPR) and outcome (voice). Limitations of pH/impedance were previously discussed in “Dose–Response Relationship” section. Here we will review the additional methods used to measure LPR exposure and voice outcomes in these studies.

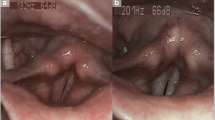

Laryngoscopic Findings

Seven of ten comparative studies used laryngoscopic findings or the reflux finding score (RFS) [32] alone or in combination with symptom severity or objective pH testing to identify patients with LPR. The RFS was developed in order to quantify laryngoscopic exam findings that are consistent with reflux into the larynx. Specificity and reliability of the RFS and laryngeal LPR findings in general, have been scrutinized and challenged by several studies [33, 34, 35•, 36–39]. In its initial validation, the RFS was found to have an inter-rater correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.90 indicating near perfect agreement among laryngologist-raters [32]. Hence documented inter-rater agreement has been less impressive, ranging from poor to fair [33, 35•, 37, 39, 40]. In one study, for example, only 35 % of those with abnormal RFS had pathological reflux on pH studies, suggesting that true identification of LPR is occurring about 1/3 of time in clinical settings that primarily rely on physical findings to diagnose LPR in symptomatic patients [38]. Other authors reported discordance between RFS and pH results in 53 % of participants referred for LPR evaluation [34].

In general, there appears to be bias toward overrating physical signs of LPR, especially given negative symptom and pH probe results. Park et al. evaluated RFS’s diagnostic characteristics and found it to have good sensitivity (87.8 %), but poor specificity (37.5 %) in detecting pharyngeal reflux positive patients [41]. This is further reinforced by several studies of normal asymptomatic controls, the majority of which had signs considered consistent with LPR [33, 42, 43]. These types of findings were even present in 73 % of asymptomatic singers [44]. It has therefore been posited that these signs represent a tissue continuum rather than distinct pathology. These ratings can also be confounded by a number of conditions and diagnostic variables including the presence of allergic rhinitis [39], type of scope used to evaluate the larynx [43], and the endoscopist a priori knowledge of patient symptoms [35]. After reviewing the evidence, the American College of Gastroenterology rejected the notion that reflux can be diagnosed by laryngoscopy alone [45••].

The vocal process granuloma is a voice-related laryngoscopic finding associated with LPR. Some suggest that its presence is pathognomonic for LPR, citing one study that found up to 65 % of patients with the condition have evidence of reflux [46]. A recent systematic review of granuloma treatment claimed level 2A evidence of PPI therapy effectiveness thereby suggesting LPR/GERD as the cause [47]. This study cannot determine that PPI therapy is effective given that no comparative effectiveness studies were among those identified. All were relatively small (mean n = 32, range 6–123) case series with wide heterogeneity in granuloma etiology. Therefore, comparison across studies is not appropriate nor is it possible to perform meta-analysis of treatment effectiveness using this literature. At best, this study describes what treatments are currently being employed for this condition. It was beyond its methodological scope to make declarative statements on the effectiveness of interventions, and it does not provide level 2A evidence supporting PPI effectiveness in treating granuloma. Interestingly and demonstrative of this is the Wang et al. study that reported a 85 % spontaneous granuloma remission rate with watchful waiting alone [48]. It is suggested that effectiveness of granuloma interventions be compared to results from these historical controls. The presence of a vocal process granuloma on laryngoscopy does not cinch the diagnosis of LPR, nor does resolution of the granuloma with PPI therapy.

Symptoms

In all, six comparative studies used symptoms or the reflux symptom index (RSI) to diagnose LPR. The RSI provided a cut-off of 13 as abnormal and indicative of LPR, thus allowing dichotomization (LPR or not), but not gradation of scores for scaling. A clinically important change was never determined for this PRO measure and it lacks precision and scaling characteristics to understand the significance of changes in scores [49]. Several methods exist to determine what represents a clinically or minimally important change [50]. Omitting this feature of interpretability represents a weakness in the RSI and in most other LPR-related PRO measures and limits their usefulness in clinical and research applications.

Specificity of this and other LPR-related patient-reported outcome measures have also been challenged. Recent studies have shown significant overlap between RSI scores suggestive of LPR and other nonreflux-related throat conditions. One found that patients with glottic insufficiency had pathologically elevated RSI scores, which normalized after its surgical correction with injection augmentation [51•]. In another, 21 patients previously diagnosed with LPR (mean RSI 16.3) were found to have alternate diagnoses [52], suggesting that the proposed cut-off for LPR is not exclusive.

Verdict: Consistency of treatment effect for patients whose symptoms have been attributed to LPR in comparative studies and clinical trials are currently lacking. This inconsistency may relate to the heterogeneity in diagnostic criteria for both LPR and voice changes.

Specificity

The concept of specificity states that an exposure will reliably produce a specific expected outcome. Laryngopharyngeal reflux has been associated with a wide range of symptoms. One symptom is voice change and it is not consistently observed in patients with reflux. In fact, a recent systematic review of LPR-related PRO measures found that voice represented a relatively small percentage of items (13 %) (Fig. 2) [49]. Even early studies from Koufman found that pH probe findings suggestive of LPR correlated best with clinic findings of subglottic stenosis (58 %) and laryngeal carcinoma (56 %) [53]. While a majority of patients (71 %) presented with “hoarseness,” only 17 % with positive pH studies had “reflux laryngitis.” The correlation of dysphonia to pH probe positivity was somewhat poor. Despite a dearth of evidence, the specificity of the relationship between reflux and dysphonia has become entrenched. In a recent study, 314 primary care physicians, 80 % reported they would treat patients with >6 weeks of voice change without known etiology with a PPI even without GERD symptoms [18••]. A presumption of LPR without laryngeal exam is dangerous as it can prevent earlier discovery of nefarious laryngeal pathology [52, 54].

The specificity of the association between reflux and voice changes has also been challenged by treatment responses. As described in “Strength of Association” and “Consistency” sections, treatment of reflux does not routinely improve voice. This is exemplified by the Park et al. study which showed that combined PPI + voice therapy was more effective than PPI alone in treating presumed LPR [30••]. Whether this result demonstrates that muscle tension dysphonia is secondary to LPR or that the majority of these patients had MTD exclusively is not clear. It suggests that a trial of high-quality voice therapy could be considered both diagnostic and therapeutic for patients without typical reflux symptoms and unremarkable laryngeal exam.

Verdict: There is a lack of specificity in symptomatology from presumed LPR. Dysphonia is among a constellation of symptoms that have been attributed to LPR, but it does not consistently or specifically improve with therapies directed at reflux.

Coherency and Analogy

A coherent relationship in clinical medicine means that the observed effect does not conflict with current knowledge of pathophysiology. Analogy requires inference between known causal relationships to further support causality of an association. Our knowledge of GERD suggests that symptoms and signs of this disease will typically respond to PPI therapy and in cases refractory to this medication, fundoplication surgery is effective in controlling symptoms.

Early uncontrolled studies of PPI treatment for LPR showed promise, reporting response rates as high as 60–70 %, but controlled trials were less promising due to a significant placebo effect [55]. Currently available comparative studies do not suggest PPI therapy is consistently effective at improving LPR-attributed voice changes. Complicating matters further is evidence from the Koufman [53] study, which states that the natural history of LPR is highly variable with 25 % of patients having spontaneous symptom remission [53]. Meta-analyses of trials of PPI for LPR have both shown moderate [56] and significant [57] effects compared to placebo on symptom scores. However, symptom indices are developmentally methodologically flawed in their development, not designed specifically to assess dysphonia and, in some cases, biased by the inclusion of traditional GERD symptoms.

Another means of assessing coherency and analogy is to consider the effect of surgical treatment on LPR patients. Nissen fundoplication represents the most definitive treatment for GERD as the lower esophageal sphincter is buttressed to prevent esophageal reflux. Since GERD exists on a pathophysiological continuum with LPR, this surgical option should be similarly effective treatment for those who have failed medical management. The outcomes of surgery on dysphonia symptoms are varied. Over 10 studies have considered this question and all but one are case series [58–71] The lone exception is a concurrent trial by Swoger et al. that compared patients without GERD whose extra-esophageal symptom was not controlled with PPI that chose to undergo fundoplication (n = 10) and second group with similar patient characteristics who opted for continued maximal medical management (n = 15) [70]. Results revealed no difference in symptom response between the two groups 12 months post-operatively (surgery 10 % vs. medical 7 %). In most studies, laryngeal symptoms, not voice changes, were assessed, thus limiting the ability to comment on them specifically.

Inclusion criteria and outcome assessment varied in case series, which intrinsically have a higher risk of bias. All performed pH monitoring pre-operatively and the majority of patients in these studies had documented GERD in addition to LPR symptoms. The most common outcome measures used were symptom response or RSI and several also used laryngoscopic findings to measure results of fundoplication on LPR. Nearly all series showed improvement in these outcomes. Patients with LPR symptoms with concomitant classic GERD symptoms and with moderate to severe reflux on preoperative pH probe studies were most likely to have resolution of LPR symptoms based on the inclusion of heartburn/regurgitation in the RSI [71]. Furthermore, in at least one study, there was substantial loss to follow-up (88 %), which introduces substantial risk of bias into its reported results [62]. Nonetheless, these studies do provide evidence that, in a carefully selected patient population with LPR symptoms, fundoplication may indeed be effective at reducing LPR-related symptoms. Despite apparent improvement in dysphonia after reflux surgery, it is unclear from these studies how to consistently predict these outcomes.

Conclusions

Voice changes are increasingly being attributed to reflux and treated with anti-reflux medications. This trend has occurred in the absence of supporting data from clinical trials. Using the Bradford Hill criteria as a rubric, the evidence toward causality between reflux and voice is insufficient. The most compelling data derived from animal studies show biological plausibility, since an acidic environment does induce mucosal changes. However, evidence from human studies is largely associative. To date, neither clinical trials nor comparative observational studies have been able to demonstrate a strong dose–response relationship between reflux and voice disorders, temporality (reflux precedes dysphonia), consistent treatment effects, or strength of association between anti-reflux treatment and improved voice among patients with presumed LPR. Nonetheless, a relationship does exist between LPR and voice and it deserves careful consideration. However, the strength and nature of that association remain unclear.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Popper KR. The logic of scientific discovery. London: Hutchinson; 1972.

Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:295–300.

Hoppo T, Sanz AF, Nason KS, et al. How much pharyngeal exposure is “normal”? Normative data for laryngopharyngeal reflux events using hypopharyngeal multichannel intraluminal impedance (HMII). J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:16–24 discussion 24–5.

Wood JM, Hussey DJ, Woods CM, et al. Biomarkers and laryngopharyngeal reflux. J Laryngol Otol. 2011;125:1218–24.

Crapko M, Kerschner JE, Syring M, et al. Role of extra-esophageal reflux in chronic otitis media with effusion. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:1419–23.

Johnston N, Wells CW, Blumin JH, et al. Receptor-mediated uptake of pepsin by laryngeal epithelial cells. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007;116:934–8.

Koufman JA. Low-acid diet for recalcitrant laryngopharyngeal reflux: therapeutic benefits and their implications. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120:281–7.

Johnston N, Bulmer D, Gill GA, et al. Cell biology of laryngeal epithelial defenses in health and disease: further studies. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112:481–91.

Johnston N, Knight J, Dettmar PW, et al. Pepsin and carbonic anhydrase isoenzyme III as diagnostic markers for laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:2129–34.

Altman KW, Kinoshita Y, Tan M, et al. Western blot confirmation of the H+/K+-ATPase proton pump in the human larynx and submandibular gland. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:783–8.

Altman KW, Haines GK 3rd, Hammer ND, et al. The H+/K+-ATPase (proton) pump is expressed in human laryngeal submucosal glands. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1927–30.

Becker V, Drabner R, Graf S, et al. New aspects in the pathomechanism and diagnosis of the laryngopharyngeal reflux-clinical impact of laryngeal proton pumps and pharyngeal pH metry in extraesophageal gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:982–7.

Adhami T, Goldblum JR, Richter JE, et al. The role of gastric and duodenal agents in laryngeal injury: an experimental canine model. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2098–106.

Delahunty JE, Cherry J. Experimentally produced vocal cord granulomas. Laryngoscope. 1968;78:1941–7.

Vaezi MF, Schroeder PL, Richter JE. Reproducibility of proximal probe pH parameters in 24-hour ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:825–9.

Merati AL, Lim HJ, Ulualp SO, et al. Meta-analysis of upper probe measurements in normal subjects and patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2005;114:177–82.

Noordzij JP, Khidr A, Desper E, et al. Correlation of pH probe-measured laryngopharyngeal reflux with symptoms and signs of reflux laryngitis. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:2192–5.

•• Ruiz R, Jeswani S, Andrews K, et al. Hoarseness and laryngopharyngeal reflux: a survey of primary care physician practice patterns. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140:192–6. An interesting survey study demonstrating how LPR has become a common diagnosis in primary care offices for persistent dysphonia.

Koufman JA, Aviv JE, Casiano RR, et al. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: position statement of the committee on speech, voice, and swallowing disorders of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:32–5.

• Ates F, Yuksel ES, Higginbotham T, et al. Mucosal impedance discriminates GERD from non-GERD conditions. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:334–43. The article describes the potential role for mucosal impedance in the diagnosis of LPR.

Fass R, Noelck N, Willis MR, et al. The effect of esomeprazole 20 mg twice daily on acoustic and perception parameters of the voice in laryngopharyngeal reflux. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22(134–41):e44–5.

Vaezi MF, Richter JE, Stasney CR, et al. Treatment of chronic posterior laryngitis with esomeprazole. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:254–60.

El-Serag HB, Lee P, Buchner A, et al. Lansoprazole treatment of patients with chronic idiopathic laryngitis: a placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:979–83.

Noordzij JP, Khidr A, Evans BA, et al. Evaluation of omeprazole in the treatment of reflux laryngitis: a prospective, placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind study. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:2147–51.

Eherer AJ, Habermann W, Hammer HF, et al. Effect of pantoprazole on the course of reflux-associated laryngitis: a placebo-controlled double-blind crossover study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:462–7.

Wo JM, Koopman J, Harrell SP, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with single-dose pantoprazole for laryngopharyngeal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1972–8 quiz 2169.

Reichel O, Dressel H, Wiederanders K, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with esomeprazole for symptoms and signs associated with laryngopharyngeal reflux. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139:414–20.

Havas T, Huang S, Levy M, et al. Posterior pharyngolaryngitis: double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial of proton pump inhibitor therapy. Aust J Otolaryngol. 1999;3:243.

Steward DL, Wilson KM, Kelly DH, et al. Proton pump inhibitor therapy for chronic laryngo-pharyngitis: a randomized placebo-control trial. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:342–50.

•• Park JO, Shim MR, Hwang YS, et al. Combination of voice therapy and antireflux therapy rapidly recovers voice-related symptoms in laryngopharyngeal reflux patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146:92–7. An important study to consider, especially for patients who have failed initial LPR treatment. As well it suggests that many patients diagnosed with LPR may have a functional cause for their dysphonia.

da Costa BR, Rutjes AW, Johnston BC, et al. Methods to convert continuous outcomes into odds ratios of treatment response and numbers needed to treat: meta-epidemiological study. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1445–59.

Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. The validity and reliability of the reflux finding score (RFS). Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1313–7.

Powell J, Cocks HC. Mucosal changes in laryngopharyngeal reflux–prevalence, sensitivity, specificity and assessment. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:985–91.

Oelschlager BK, Eubanks TR, Maronian N, et al. Laryngoscopy and pharyngeal pH are complementary in the diagnosis of gastroesophageal–laryngeal reflux. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:189–94.

• Chang BA, MacNeil SD, Morrison MD, et al. The reliability of the reflux finding score among general otolaryngologists. J Voice. 2015;29:572–7. An important study to consider when evaluating other trials whose inclusion criteria and/or treatment response relies upon the RFS.

Branski RC, Bhattacharyya N, Shapiro J. The reliability of the assessment of endoscopic laryngeal findings associated with laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1019–24.

Kelchner LN, Horne J, Lee L, et al. Reliability of speech-language pathologist and otolaryngologist ratings of laryngeal signs of reflux in an asymptomatic population using the reflux finding score. J Voice. 2007;21:92–100.

Musser J, Kelchner L, Neils-Strunjas J, et al. A comparison of rating scales used in the diagnosis of extraesophageal reflux. J Voice. 2011;25:293–300.

Eren E, Arslanoglu S, Aktas A, et al. Factors confusing the diagnosis of laryngopharyngeal reflux: the role of allergic rhinitis and inter-rater variability of laryngeal findings. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271:743–7.

Mesallam TA, Stemple JC, Sobeih TM, et al. Reflux symptom index versus reflux finding score. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007;116:436–40.

Park KH, Choi SM, Kwon SU, et al. Diagnosis of laryngopharyngeal reflux among globus patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:81–5.

Hicks DM, Ours TM, Abelson TI, et al. The prevalence of hypopharynx findings associated with gastroesophageal reflux in normal volunteers. J Voice. 2002;16:564–79.

Milstein CF, Charbel S, Hicks DM, et al. Prevalence of laryngeal irritation signs associated with reflux in asymptomatic volunteers: impact of endoscopic technique (rigid vs. flexible laryngoscope). Laryngoscope. 2005;115:2256–61.

Lundy DS, Casiano RR, Sullivan PA, et al. Incidence of abnormal laryngeal findings in asymptomatic singing students. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121:69–77.

•• Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308–28; quiz 329. This article comes from the GI literature and concludes that laryngoscopy alone is not a reliable diagnostic tool for LPR. This conclusion and treatment guideline oppose those in the ENT literature.

Ylitalo R, Ramel S. Extraesophageal reflux in patients with contact granuloma: a prospective controlled study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111:441–6.

Karkos PD, George M, Van Der Veen J, et al. Vocal process granulomas: a systematic review of treatment. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2014;123:314–20.

Wang CP, Ko JY, Wang YH, et al. Vocal process granuloma—a result of long-term observation in 53 patients. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:821–5.

Francis DO, Sharda R, Patel DA, et al. Developmental characteristics of patient-reported outcome measures related to laryngopharyngeal reflux: a systematic review. 2016 (under review).

Guyatt GH, Osoba D, Wu AW, et al. Methods to explain the clinical significance of health status measures. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:371–83.

• Patel AK, Mildenhall NR, Kim W, et al. Symptom overlap between laryngopharyngeal reflux and glottic insufficiency in vocal fold atrophy patients. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2014;123:265–70. This article demonstrates that other laryngeal disorders can mimic the clinical presentation of LPR. This is particularly important given that many PCPs are treatment with PPI prior to laryngoscopic evaluation by an ENT.

Rafii B, Taliercio S, Achlatis S, et al. Incidence of underlying laryngeal pathology in patients initially diagnosed with laryngopharyngeal reflux. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:1420–4.

Koufman JA. The otolaryngologic manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): a clinical investigation of 225 patients using ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring and an experimental investigation of the role of acid and pepsin in the development of laryngeal injury. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:1–78.

Sulica L. Hoarseness misattributed to reflux: sources and patterns of error. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2014;123:442–5.

Qadeer MA, Lopez R, Wood BG, et al. Does acid suppressive therapy reduce the risk of laryngeal cancer recurrence? Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1877–81.

Qadeer MA, Phillips CO, Lopez AR, et al. Proton pump inhibitor therapy for suspected GERD-related chronic laryngitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2646–54.

Guo H, Ma H, Wang J. Proton pump inhibitor therapy for the treatment of laryngopharyngeal reflux: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:295–300.

Lindstrom DR, Wallace J, Loehrl TA, et al. Nissen fundoplication surgery for extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux (EER). Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1762–5.

Westcott CJ, Hopkins MB, Bach K, et al. Fundoplication for laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:23–30.

Ogut F, Ersin S, Engin EZ, et al. The effect of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication on laryngeal findings and voice quality. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:549–54.

Sahin M, Vardar R, Ersin S, et al. The effect of antireflux surgery on laryngeal symptoms, findings and voice parameters. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272:3375–83.

Catania RA, Kavic SM, Roth JS, et al. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication effectively relieves symptoms in patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1579–87 discussion 1587–8.

Sala E, Salminen P, Simberg S, et al. Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease treated with laparoscopic fundoplication. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2397–404.

Wassenaar E, Johnston N, Merati A, et al. Pepsin detection in patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux before and after fundoplication. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3870–6.

van der Westhuizen L, Von SJ, Wilkerson BJ, et al. Impact of Nissen fundoplication on laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms. Am Surg. 2011;77:878–82.

Trad KS, Turgeon DG, Deljkich E. Long-term outcomes after transoral incisionless fundoplication in patients with GERD and LPR symptoms. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:650–60.

Weber B, Portnoy JE, Castellanos A, et al. Efficacy of anti-reflux surgery on refractory laryngopharyngeal reflux disease in professional voice users: a pilot study. J Voice. 2014;28:492–500.

Hamdy E, El Nakeeb A, Hamed H, et al. Outcome of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease in non-responders to proton pump inhibitors. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:1557–62.

Hamdy E, El-Shahawy M, Abd El-Shoubary M, et al. Response of atypical symptoms of GERD to antireflux surgery. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:403–6.

Swoger J, Ponsky J, Hicks DM, et al. Surgical fundoplication in laryngopharyngeal reflux unresponsive to aggressive acid suppression: a controlled study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:433–41.

Francis DO, Goutte M, Slaughter JC, et al. Traditional reflux parameters and not impedance monitoring predict outcome after fundoplication in extraesophageal reflux. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1902–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

G. Todd Schneider, Michael F. Vaezi, and David O. Francis declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Professional Voice Disorders.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Todd Schneider, G., Vaezi, M.F. & Francis, D.O. Reflux and Voice Disorders: Have We Established Causality?. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep 4, 157–167 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40136-016-0121-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40136-016-0121-5