Abstract

Purpose of Review

There is a critical need for corporations to be part of the solutions to major societal issues, such as obesity. Investment decisions can have a substantial impact on both corporate practices and population health. This paper aimed to explore potential mechanisms for incorporating obesity and related nutrition considerations into responsible investment (RI) approaches.

Recent Findings

We found that there are a number of available strategies for the investment community to incorporate obesity considerations into their decisions. However, despite some recent efforts to improve company disclosure in the area and the emergence of new tools for assessing food company nutrition policies, the inclusion of obesity and related nutrition considerations as part of RI is currently extremely limited.

Summary

There appears to be substantial scope to apply approaches already in widespread use for other RI considerations to the area of obesity. Ways in which to apply measurement frameworks across different markets and sectors need to be explored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and obesity are leading contributors to mortality and morbidity globally and represent an ongoing public health crisis [1]. Poor diets as a result of unhealthy food environments are major drivers of obesity and a range of NCDs and have wide-ranging negative impacts on health systems, the economy and levels of productivity [2]. Tackling poor diets through improvements to the food environment requires a comprehensive societal response, including government policies and wide-scale action from the food industry [3]. Whilst some steps have been taken by governments to address these issues, the development and implementation of recommended policies and actions have been slow and inadequate globally [4•]. Importantly, many governments have favoured a voluntary, industry-guided approach in key policy areas, such as product reformulation, reducing promotion of unhealthy food to children, and nutrition labelling [5]. These non-regulatory approaches have thus far been shown to be largely ineffectual at addressing obesity and improving population nutrition [6,7,8]. Whilst many prominent food companies have made some commitment to address obesity-related issues, voluntary company policies and commitments are often non-specific and limited in scope, with poor monitoring and compliance mechanisms in place [9,10,11]. In order to shift current practices of food companies to adopt key recommendations related to obesity, a range of mechanisms for influencing corporate behaviour needs to be considered.

Responsible investment (RI), also referred to as ‘socially responsible investment’, is an approach to investing that aims to incorporate environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors into investment decisions, in addition to financial goals [12•]. There are a number of approaches that can be taken to incorporate these concerns into the investment process. Most commonly, this is done through socially responsible investment funds that exclude or include companies, sectors and stocks based on ESG criteria [13, 14]. In recent years, there has been an increase in support for RI approaches in major investment markets, with RI continuing to gain interest globally amid increased efforts to make RI more mainstream [12•, 15•, 16,17,18]. For investors, reasons for investing in socially responsible and ethical options include the creation of long-term shareholder value, and reduction of risk [19]. For the broader community, reasons for RI include benefiting the welfare of communities, helping to influence the policy debate on issues of public interest, and putting pressure on corporations to consider whether their actions are socially responsible [16]. The influence of the investment community, coupled with related advocacy, has played a key role in increasing corporate accountability across a range of areas such as human rights, labour rights and environmental protections [20,21,22]. RI has been shown to increase shareholder satisfaction, [23] and whilst not universally true, it has been shown to positively impact investment returns in some cases [24,25,26]. For these reasons, RI represents a potentially important opportunity for driving greater action from companies with respect to addressing poor diets and associated rates of obesity and NCDs.

This research aimed to investigate the extent to which obesity and related nutrition issues are a consideration in prominent RI approaches globally. We also explored potential mechanisms for including obesity and related nutrition considerations as part of the RI process, whilst identifying some foreseeable challenges.

Methods

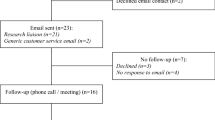

We conducted a narrative review of the academic literature with a focus on identifying papers that discussed ways in which obesity and nutrition considerations have been, or could be, included as part of RI approaches. We searched both business- and health-related databases (including Ebscohost databases, Informit, Proquest and Pubmed). The search strategy incorporated terms related to obesity, nutrition and RI (including socially responsible investment, ethical investment and sustainable investment). Whilst our focus was on RI in relation to obesity and nutrition, we also considered papers that mentioned RI with regard to other aspects of NCDs, such as tobacco and alcohol, in order to identify potentially applicable RI strategies. We also searched the reference lists of relevant papers to identify additional articles for consideration. The academic literature search was supplemented by a grey literature search using the same search terms in Google, with the first 10 pages of results screened for relevant websites and studies not found in the academic database searches.

We also searched the websites of prominent investment and RI institutions and United Nations (UN) organisations. On these websites, we looked for reviews and reports that discussed RI strategies, trends, and recommendations at the global and country level. We focused on literature that referenced health and nutrition-related RI options, as well as RI in relation to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

We concentrated on RI with respect to food companies (defined here as food and non-alcoholic beverage manufacturers, fast food restaurants and food retailers) and did not explicitly consider other sectors related to obesity, such as the pharmaceuticals, sports apparel and equipment, health care and commercial weight loss sectors.

Results

Our search of the academic literature did not locate any studies specifically focused on obesity- and nutrition-related considerations with respect to RI. Where health issues were explicitly examined with respect to RI, the focus was typically on tobacco- and alcohol-related issues. The grey literature search found several industry reports and business initiatives linking obesity and nutrition with RI. In addition, much of literature concerning RI discussed issues that are relevant to obesity- and nutrition-related considerations, even when these considerations were not explicitly identified. The findings from the review are structured as follows: firstly, we present key initiatives from the UN relevant to RI, as an over-arching global framework for considering RI issues; secondly, we present a summary of RI strategies that have been applied across a range of ESG criteria, as well as discussing their relevance to obesity and related nutrition issues; and thirdly, we present out findings regarding the extent to which obesity and related nutrition issues have been considered as part of prominent RI strategies globally.

The United Nations and the Sustainable Development Goals

The UN SDGs and associated targets, adopted in 2015 by all 193 member states of the UN, present an agenda for all parts of society, including the corporate sector and investment community, to work towards improved economic prosperity and the health and wellbeing of people and the planet by 2030 [27••]. Improving population nutrition represents an important step in achieving the SDGs, with nutrition considered a component of all 17 SDGs, and is part of, or linked to, performance targets of several SDGs [28].

The UN identifies the business and investment community as playing a key role in contributing to the SDGs [27••]. They have developed a set of resources to guide companies on how they can align their strategies as well as measure and manage their contribution to the SDGs. One example of these resources is the SDG Compass, which presents a series of steps (understand the SDGs, define priorities, set goals, integrate, monitor and report) that can be used to assist companies in maximising their contribution to the SDGs [29]. There is emerging evidence that the so-called sustainability agenda has started to shift the focus of transnational corporations and financial investors, who are increasingly monitoring and evaluating their contributions to the SDGs [30].

The SDG Compass, and associated resources, builds on the UN Global Compact initiative, launched in 2000, that aims to encourage businesses worldwide to adopt sustainable and socially responsible policies and to report on their implementation [29]. The UN Global Compact (comprising over 12,000 signatories as of 2018) bases its sustainability approach on key principles in the areas of human rights, labour, environment and anti-corruption [31]. Importantly, however, the UN Global Compact does not include a principle that explicitly addresses nutrition, human health and/or wellbeing of populations [32].

The UN has also supported the development and application of Principles for Responsible Investing (PRI) [33••]. The principles recognise that institutional investors have a duty to act in the best long-term interests of their beneficiaries and are designed to help align the goals of investors with broader objectives of society, taking into account ESG issues. The PRI, as an organisation, works to support institutional investors globally to incorporate ESG factors into their investment and ownership decisions [33••]. As of 2017, there were > 1000 signatories to the PRI, with increasing take-up amongst institutional investors [34]. Whilst the PRI make reference to the SDGs, they do not explicitly highlight obesity and related nutrition issues, and, for the most part, population health issues receive very little prominence in their tools and resources.

All of the above-mentioned initiatives provide a global framework within which health, obesity and nutrition impacts can be incorporated and considered, amongst multiple other considerations, as part of investment and business decisions.

Responsible Investment Strategies

There is a range of strategies that can be used to integrate ESG considerations into investment decisions [12•, 15•, 35]. These can be broadly categorised as follows: screening strategies, which include or exclude companies and stocks from investment portfolios based on ESG criteria; impact investment, which involves investment made into companies or funds with the intention to generate a measurable, beneficial social or environmental impact alongside a financial return; and shareholder activism, which involves direct corporate engagement to address ESG concerns [14, 36, 37]. Table 1 provides a more detailed overview of the commonly available strategies, based on the frameworks proposed by prominent responsible investment industry bodies Eurosif [12•, 39] and the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance [15•, 40, 41]. The most commonly applied strategy is negative/exclusionary screening (USD15 trillion globally in 2016), followed by ESG integration (USD10.37 trillion globally in 2016) and shareholder activism (USD8.3 trillion globally in 2016) [15•]. However, this can vary from country to country. Examples of ways in which each strategy could be applied to obesity and related nutrition issues (with respect to food companies) are also described in Table 1 and discussed in more detail in the sections that follow.

Obesity and Nutrition as Considerations in Prominent Responsible Investment Strategies Globally

There are a large number of RI indices available globally. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the Dow Jones Sustainability Indices (DJSI) are amongst the most recognised and widely used sustainability performance-reporting frameworks to assess and report on companies based on multiple aspects of their ESG performance [42, 43]. The GRI is used by 83% of the top 250 companies globally [44••], whilst the DJSI (which are based on an assessment by RobecoSAM) spans 60 industries and sectors and includes 3400 companies globally [45•]. Both apply a standardised sustainability-reporting methodology that includes hundreds of indicators related to ESG factors. Whilst obesity and related nutrition are very minor components of each of these frameworks, both of them contain some disclosure requirements and assessment indicators in the area.

A key aspect of the GRI are the GRI Standards, which provide voluntary global standards for sustainability reporting in relation to a range of economic, environmental and social impacts. Their most specific reporting requirements with respect to obesity and related nutrition issues are the G4 Sector Disclosures for food processing companies (relevant to all companies that are engaged in processing of food and beverages) [46]. As part of these disclosure requirements, food companies are invited to report details of their sales of products categorised according to their healthiness, and their policies and practices on nutrition labelling and marketing (with particular emphasis on marketing to vulnerable groups) [46]. Information on the extent to which relevant companies comply with these voluntary disclosure requirements, or the impact they have on corporate practices and investment decisions is not readily available.

Under the RobecoSAM corporate sustainability assessment methodology which underlies the DJSI, companies in the food and beverage industry are asked to disclose information on their activities related to nutrition reformulation, self-regulation of marketing related to nutrition, and their overall health and nutrition strategy [47]. In addition, companies are asked to disclose if they have measured the impact of their social and/or environmental externalities (consequence of an activity that affects other unrelated parties without being reflected in market prices) not currently reflected in financial accounting factors. For food and beverage companies, RobecoSAM explicitly notes that negative externalities that could be considered here include the ‘overconsumption of products containing sugar’ [48]. All of these aspects are factored into the overall corporate sustainability assessment that gives companies a sustainability score (out of 100), used as the backbone for the DJSI. Once again, the extent to which companies voluntarily disclosure relevant information, and the impact it has on their overall sustainability score are not readily available.

Whilst the above-mentioned reporting frameworks are designed to support positive screening, many RI institutions adopt a negative screening approach to RI. Our review of industry body reports identified a range of ‘sin stocks’ that are commonly being screened for exclusion by RI institutions across global markets (see Table 2 for examples). In relation to health, tobacco was one of the most common negative screens applied in RI strategies, with screens for alcohol and gambling also being frequently used [24, 42]. This is consistent with academic literature that notes that tobacco, alcohol and gambling have historically been screened for based on market trends, societal norms and consumer values [24]. We were not able to identify any prominent RI schemes that suggested obesity or related nutrition factors were considered as part of a negative/exclusionary screening strategy.

Our search revealed only a small number of examples in which obesity and related nutrition factors were noted as explicit considerations as part of other current RI strategies. The Access to Nutrition Index (ATNI) is an initiative that benchmarks the top 20 global food and beverage manufacturers on their policies and commitments related to obesity prevention and nutrition, and uses a rigorous assessment methodology that was developed over several years with extensive input from food companies, public health researchers and the investment community [38••]. As part of ATNI, food company policies, disclosure and transparency practices are assessed against a range of indicators related to obesity and population nutrition, with the intention of monitoring company progress over time [38••]. As of June 2018, over 60 investment firms had signed ATNI’s investor statement that includes a commitment to factor ATNI’s results into investment analysis with respect to the food and beverage manufacturing sector [51]. The extent to which investors have done this, their mechanisms for doing so and the influence of ATNI on investor decision making is not currently available. Other examples of RI strategies relating to obesity included targeted investment in companies that aim to promote healthy lifestyles [52], and industry reports that identify ways in which obesity-related considerations could be considered in investment decisions, as well as investor risks associated with obesity [53, 54]. The Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN), a not-for-profit organisation focused on increasing the scale and effectiveness of impact investing, hosts a catalogue of Impact Reporting and Investment Standards (IRIS), designed to make it easier for impact investors to understand generally accepted social and environmental performance metrics [55]. Amongst the list of hundreds of indicators in IRIS for impact investors to consider, none explicitly mention obesity, and only very few relate directly to nutrition (e.g. there is one metric around the provision of school meals and several around food security) [56].

Discussion

This review found that there are a number of available strategies for the investment community to incorporate obesity and related nutrition considerations into their decision making. Several UN initiatives, including the SDGs, provide a global framework within which obesity and related nutrition impacts can be incorporated and considered as part of investment and business decisions. In addition, a range of RI approaches currently used across a range of other social and environmental domains could be applied to the area of obesity and related nutrition. Whilst there have been recent efforts to establish disclosure requirements and measurement criteria in the area, the inclusion of obesity and related nutrition considerations as part of RI is currently extremely limited amongst the most prominent investment institutions. Where obesity considerations are part of relevant global reporting frameworks, there is a complete reliance on voluntary company disclosure, assessment metrics are not well established, and the weighting given to the issue is negligible.

Screening strategies (exclusion and inclusion) appear to be the most likely mechanisms for incorporating obesity and related nutrition considerations into responsible investment at scale. Exclusionary (negative) screening for other health-related issues (such as tobacco, alcohol and gambling) has been a successful approach and is now relatively commonly adopted as part of RI approaches globally. However, it is likely that using an exclusionary screening approach with respect to obesity will be more challenging. One reason for this is that tobacco, alcohol and gambling are widely considered to raise traditional ESG concerns [57]; whereas, this is not necessarily the case in relation to food products. Whilst tobacco, alcohol and gambling stocks are related to ill-health, initial efforts to exclude them from investment portfolios as ‘sin stocks’ were, in many cases, driven by religious (rather than health) values [17]. It is highly likely that, unlike tobacco, applying a screen to the whole food and beverage industry would not be acceptable to key stakeholders, primarily because the majority of large food companies manufacture both healthier and less healthy products. One approach could be to consider certain food products that heavily contribute to poor health, and screen for companies that predominately produce (or earn the majority of their revenue from) those selected products. Sugar sweetened beverage (SSB) manufacturers could be a candidate for this approach, as SSBs are widely acknowledged to have little nutritional value and there is a strong evidence base supporting the relationship between SSBs and poor health outcomes [58]. Alternatively, companies could be given an overall score based on the nutrient profile of their entire product range and be excluded from investments if their score fell below a selected threshold. This type of product portfolio assessment has recently been conducted in relation to the largest food and beverage manufacturers globally as part of ATNI [59]. A key challenge to this approach is gaining agreement on an appropriate nutrient profiling system that classifies products for this purpose, but the recent endorsement of nutrient profiling schemes by a number of WHO regions and national governments [60,61,62,63] indicates increasing consensus regarding nutrient profiling schemes. If a product portfolio assessment approach is to be further explored for investment purposes, the potential for increased market concentration (e.g. companies with a traditionally unhealthy product portfolio acquiring companies with a healthier set of products) and any resulting negative consequences will need to be taken into account.

Inclusionary (positive) screening could also be a way of applying obesity considerations to RI, with a focus on the food and beverage manufacturing and retailing sectors. In recent years, a number of measurement tools have been developed for benchmarking food company performance in this area. ATNI is the most prominent example, having been regularly applied to the food and beverage manufacturing sector at the global level and at the national level in a small number of countries [38••]. INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/NCDs Research, Monitoring and Action Support) [64]—a global network of public health researchers that monitors and benchmarks food environments—has also recently developed a tool, based on ATNI, to assess food companies policies and commitments related to obesity prevention and nutrition. The INFORMAS BIA-Obesity (Business Impact Assessment—obesity and population nutrition) tool is designed to be applied at the national level, with tailored assessment criteria for food and beverage manufacturers, fast food restaurants and supermarkets [65]. Both ATNI and the BIA-Obesity tool could potentially be used a mechanism for positive screening. However, in its current format, ATNI could only be applied to the food and beverage manufacturing sector, and would need to be adapted and applied to suit local markets. Importantly, both tools only currently consider company policies and commitments and do not assess company practices and real world impact on obesity and related nutrition. This is an issue more generally within RI, whereby the majority of emphasis is currently focused on financial performance and self-reporting, rather than actual performance of companies in relation to ESG criteria [66•].

Whilst it is encouraging to see obesity and related nutrition considerations feature as part of globally applicable RI reporting frameworks, such as the GRI Standards, and corporate sustainability assessment criteria, such as the DJSI, they remain extremely minor components of those frameworks. Whilst sustainability assessment across a broad range of domains allows the incorporation of a large number of ESG factors and promotes comparability across sectors, it also diminishes the importance of individual criteria. For example, large composite indices such as the DJSI are likely to be insufficiently sensitive to assist an investor looking to minimise investment in food companies that market and sell predominantly unhealthy products. Moreover, company disclosure in the area is currently completely voluntary, with limited sanctions available for non-disclosure. This points to the need to explore mechanisms for mandatory sustainability reporting as well as highly sector-specific indicators of performance with respect to ESG criteria [67].

Integrating nutrition and obesity considerations into prominent RI strategies will require the development of standardised measurement tools for assessing companies, and support for their implementation at the country level. It will be important for these tools to consider a variety of other factors, including the country’s financial market, culture, values and legal system, as the principles of responsible investment can vary substantially from country to country [35, 68].

Conclusion

The investment community holds significant power and influence over corporate behaviour and investment practices. RI is becoming increasingly popular and reflects a growing push from organisations like the UN to draw on company and investor action to address systemic environmental, health and wellbeing issues. Whilst businesses and investors are addressing many aspects of environmental and social targets within social responsibility frameworks, they are largely failing to seriously consider options for incorporating business impact on obesity and related nutrition issues. Whilst there are some promising tools that measure and assess food company impact on obesity and nutrition, these tools have not yet been broadly applied across different markets and sectors, and do not address all relevant aspects of corporate impact on obesity. Nevertheless, there appears to be substantial scope to apply strategies already in widespread use for other RI considerations to the area of obesity, and integrate them with other RI approaches. It will take a significant cultural and social change process to reorient the current strategies and considerations of the vast majority of investors such that obesity-related considerations are comprehensively considered. The public health community needs to strengthen relationships with the investment community, and seek to better understand the barriers and enablers of change within the investment system.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major Importance

World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases 2013-2020. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [cited March 2018]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/94384/1/9789241506236_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1.

World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Geneva: WHO; 2011. [cited April 2018]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44579/9789240686458_eng.pdf;jsessionid=A2509EA9F14FC4ED0CCA21E1CE003A24?sequence=1.

Swinburn B, Sacks G, Vandevijvere S, Kumanyika S, Lobstein T, Neal B, et al. INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support): overview and key principles. Obes Rev. 2013(S1):1.

• Swinburn B, Kraak V, Rutter H, Vandevijvere S, Lobstein T, Sacks G, et al. Strengthening of accountability systems to create healthy food environments and reduce global obesity. Lancet. 2015;385(9986):2534–45. Outlines mechanism to increase accountability for obesity prevention across a range of sectors.

Mialon M, Swinburn B, Sacks G. A proposed approach to systematically identify and monitor the corporate political activity of the food industry with respect to public health using publicly available information. Obes Rev. 2015;16(7):519–30.

Kunkel DL, Castonguay JS, Filer CR. Evaluating industry self-regulation of food marketing to children. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2):181–7.

Magnusson R, Reeve B. Food reformulation, responsive regulation, and “regulatory scaffolding”: strengthening performance of salt reduction programs in Australia and the United Kingdom. Nutrients. 2015;7(7):5281–308.

Ronit K, Jensen JD. Obesity and industry self-regulation of food and beverage marketing: a literature review. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68(7):753–9.

Jones A, Magnusson R, Swinburn B, Webster J, Wood A, Sacks G, et al. Designing a healthy food partnership: lessons from the Australian food and health dialogue. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):651.

Sacks G, Robinson E, for INFORMAS. Inside our food and beverage manufacturers: assessment of company policies and commitments related to obesity prevention and nutrition. Melbourne: Deakin University; 2018. [cited May 2018]. Available from: https://www.insideourfoodcompanies.com.au/foodandbev.

Knai C, Petticrew M, Durand MA, Eastmure E, James L, Mehrotra A, et al. Has a public–private partnership resulted in action on healthier diets in England? An analysis of the public health responsibility deal food pledges. Food Policy. 2015;54:1–10.

• European Sustainable and Responsible Investment Forum (Eurosif). European SRI study 2016. Brussels: Eurosif; 2016. Prominent industry report outlining key responsible investment trends in Europe.

Ito Y, Managi S, Matsuda A. Performances of socially responsible investment and environmentally friendly funds. J Oper Res Soc. 2013;64(11):1583–94.

Pérez-Gladish B, Rodríguez PM, M'Zali B, Lang P. Mutual funds efficiency measurement under financial and social responsibility criteria. J Multi-Criteria Decis Anal. 2013;20(3–4):109–25.

• Global Sustainable Investment Alliance. Global sustainable investment review 2016. [cited February 2018]. Available from: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/GSIR_Review2016.F.pdf. Prominent industry report outlining key responsible investment trends in major markets globally.

The Forum for Sustainble and Responsible Investment (US SIF). The impact of sustainable and responsible investment. Washington: US SIF; 2016.

Sparkes R, Cowton CJ. The maturing of socially responsible investment: a review of the developing link with corporate social responsibility. J Bus Ethics. 2004;52(1):45–57.

The Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment (US SIF). Report on US sustainable, responsible and impact investing trends 2016. Executive summary. Washington: US SIF; 2016.

RobecoSAM. Sustainability assessment: corporate sustainability 2018. [cited May 2018]. Available from: http://www.sustainability-indices.com/sustainability-assessment/corporate-sustainability.jsp.

Wagemans FAJ, van Koppen CSA, Mol APJ. The effectiveness of socially responsible investment: a review. J Integr Environ Sci. 2013;10(3–4):235–52.

Arjaliès D-L. A social movement perspective on finance: how socially responsible investment mattered. J Bus Ethics. 2010;92(1):57–78.

Guay T, Doh JP, Sinclair G. Non-governmental organizations, shareholder activism, and socially responsible investments: ethical, strategic, and governance implications. J Bus Ethics. 2004;52(1):125–39.

Renneboog L, Ter Horst J, Zhang C. Socially responsible investments: institutional aspects, performance, and investor behavior. J Bank Financ. 2008;32(9):1723–42.

Hong H, Kacperczyk M. The price of sin: the effects of social norms on markets. J Financ Econ. 2009;93(1):15–36.

Margolis JD, Walsh JP. Misery loves companies: rethinking social initiatives by business. Adm Sci Q. 2003;48(2):268–305.

Orlitzky M, Schmidt FL, Rynes SL. Corporate social and financial performance: a meta-analysis. Organ Stud. 2003;24(3):403–41.

•• United Nations. Sustainable development goals. New York: United Nations; 2015. [cited 2018 March]. Available from: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/. The UN SDGs and associated targets present an agenda for all parts of society, including the corporate sector and investment community, to work towards improved economic prosperity, and the health and wellbeing of people and the planet by 2030.

Development Initiatives. Global nutrition report 2017: nourishing the SDGs. Bristol: Development Initiatives; 2017.

Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), United Nations (UN) Global Compact, World Business Council For Sustainable Development (WBCSD). SDG Compass: the guide for business action on the SDGs. 2015. [cited May 2018]. Available from: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/issues_doc/development/SDGCompass.pdf.

Hellström E, Hämäläinen T, Lahti V, Cook J, Jousilahti J. Towards a sustainable well-being society from principles to applications. Sitra Working Paper 14 [Internet]. 2015. Mar 2018. Available from: https://media.sitra.fi/2017/02/23221124/Towards_a_Sustainable_Wellbeing_Society_2.pdf.

United Nations Global Compact. Making global goals local business: a new era for responsible business. New York: United Nations; 2017.

Kraak V, Swinburn B, Lawrence M, Harrison P. The accountability of public–private partnerships with food, beverage and restaurant companies to address global hunger and the double burden of malnutrition. SCN News Nutrition and Business: How to Engage? [Internet]. 2011. Mar 2018; 39:[11–24 pp.]. Available from: http://www.unscn.org/files/Publications/SCN_News/SCNNEWS39_10.01_high_def.pdf.

•• UNPRI. Principles for responsible investment 2018. [cited May 2018]. Available from: https://www.unpri.org/. Document outlining the key principles for responsible invesment, supported by the United Nations.

UNPRI. Principles for resposible investment: annual report 2017. [cited May 2018]. Available from: https://annualreport.unpri.org/docs/PRI_AR-2017.pdf.

European Sustainable and Responsible Investment Forum (Eurosif). Socially responsible investment among European Institutional Investors: 2003 report. Paris: Eurosif; 2003.

Biedermann DF. Integrating non-financial and ethical criteria into the investment process. London: IBC Global Conferences Limited; 2000.

Louche CLS. Responsible investing (chapter 21). In: Boatright JR, editor. Finance ethics: critical issues in theory and practice. Hoboken: Wiley; 2010. p. 393–434.

•• Access to Nutrition Index. Access to Nutrition Index: global index 2018. [cited May 2018]. Available from: http://www.accesstonutrition.org. Global tool used to assess and benchmark food and beverage manufacturers on their performance against a range of indicators related to obesity prevention and population nutrition.

European Sustainable and Responsible Investment Forum (Eurosif). European SRI study 2012. Brussels: Eurosif; 2012.

Global Sustainable Investment Alliance. Global sustainable investment review 2012. [cited 2018 March]. Available from: http://gsiareview2012.gsi-alliance.org/#/1/.

Global Sustainable Investment Alliance. Global sustainable investment review 2014. [cited March 2018]. Available from: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/GSIA_Review_download.pdf.

de Bruin B. Socially responsible investment in the alcohol industry: an assessment of investor attitudes and ethical arguments. Contemporary Social Science. 2013.

RobecoSAM. Results announced for 2017 Dow Jones sustainability indices review 2017. [cited 2017 March]. Available from: http://www.sustainability-indices.com/images/170907-djsi-review-2017-en-vdef.pdf.

•• Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). GRI Standards 2018. [cited March 2018]. Available from: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards. Details of the reporting methodology used by the GRI to assess the perfomance of the corporate sector against specific ESG criteria.

• RobecoSAM. CSA guide—RobecoSAM’s coporate sustainability assesment methodology 2016. [cited March 2018]. Version 4.0. Available from: http://www.sustainability-indices.com/images/corporate-sustainability-assessment-methodology-guidebook.pdf. Outlines framework for measuring corporate sustainability performance and is the foundation for the Dow Jones Sustainability Indices.

Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). G4 sector disclosures: food processing 2014. [cited May 2018]. Available from: https://www.globalreporting.org/resourcelibrary/GRI-G4-Food-Processing-Sector-Disclosures.pdf.

RobecoSAM. RobecoSAM’s corporate Sustainability assessment companion Zurich, 2018. [cited 2018]. Available from: http://www.robecosam.com/images/RobecoSAM-Corporate-Sustainability-Assessment-Companion-en.pdf.

RobecoSam. Coporate sustainability assessment—annual scoring and methodology review 2017. [cited May 2018]. Available from: http://www.robecosam.com/images/CSA_2017_Annual_Scoring_Methodology_Review.pdf.

Responsible Investment Association Australasia. Responsible investment benchmark report 2016. Sydney: Responsible Investment Association Australasia; 2016.

Responsible Investment Association Australasia. Responsible investment benchmark report 2017. Sydney: Responsible Investment Association Australasia; 2017.

Access to Nutrition Index. Access to Nutrition Index investor statement. [cited June 2018]. Available from: https://www.accesstonutrition.org/sites/in16.atnindex.org/files/atni_investor_statement_20130310_1.pdf.

RobecoSam. Sustainable healthy living strategy 2018. [cited May 2018]. Available from:. http://www.robecosam.com/images/RobecoSAM_Healthy_Living_en.pdf.

Irving E, Crossman M, Rathbone Greenbank. Sugar, obesity and noncommunicable disease: investor expectations. London: Shroders & Rathbone Greenbank; 2017. [cited May 2018]. Available from: http://www.schroders.com/en/sysglobalassets/news/sugar-investor-expectations-report.pdf.

Bank of America Merrill Lynch. Globesity—the global fight against obesity. 2012. [cited May 2018]. Available from: http://www.foresightfordevelopment.org/sobipro/55/1260-globesity-the-global-fight-against-obesity.

Global Impact Investing Network. About IRIS 2010–2018. [cited May 2018]. Available from: https://iris.thegiin.org/about-iris.

Global Impact Investing Network. IRIS metrics 2016. [cited May 2018]. Available from: https://iris.thegiin.org/metrics.

Trinks PJ, Scholtens B. The opportunity cost of negative screening in socially responsible investing. J Bus Ethics. 2017;140(2):193–208.

Scharf RJ, DeBoer MD. Sugar-sweetened beverages and children’s health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37:273–93.

Access to Nutrition Index. 2018 Global ATNI product profile methodology—study undertaken by the George Institute for Global Health 2018. [cited may 2018]. Available from: https://www.accesstonutrition.org/sites/in16.atnindex.org/files/2018_gi_pp_methodology_.pdf.

Breda J, Jewell J, Nishida C, Galea G. WHO regional office for Europe nutrient profile model. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2015.

Department of Health, Australia. Health star rating. [cited May 2018]. Available from: http://healthstarrating.gov.au.

WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific. WHO nutrient profile model for the Western Pacific Region: a tool to protect children from food marketing. Manila: World Health Organization; 2016.

Pan American Health Organization. Pan American health organization nutrient profile model. Washington: Pan American health Organization; 2016.

Swinburn B, Sacks G, Vandevijvere S, Kumanyika S, Lobstein T, Neal B, et al. INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support): overview and key principles. Obes Rev. 2013:14 Suppl 1:1–12.

Sacks G, et al. BIA-Obesity: methods for assessment of company policies and commitments related to obesity prevention and nutrition. [cited May 2018]. Available from: www.insideourfoodcompanies.com/assessment-tool.

• van Dijk-de Groot M, Nijhof AHJ. Socially responsible investment funds: a review of research priorities and strategic options. J Sustain Fin Inves. 2015;5(3):178–204. Literature review of Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) funds that examines the different themes underlying SRI research, e.g., financial performance, social performance, SRI principles.

Lydenberg S, Rogers J, Wood D. From transparency to performance: industry-based sustainability reporting on key issues. 2010. [cited May 2018]. Available from: https://iri.hks.harvard.edu/links/transparency-performance-industry-based-sustainability-reporting-key-issues.

Scholtens B, Sievänen R. Drivers of socially responsible investing: a case study of four Nordic countries. J Bus Ethics. 2013;115(3):605–16.

Acknowledgements

GS is the recipient of an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE160100307) and a researcher within a NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence in Obesity Policy and Food Systems (APP1041020) (Australia).

The publisher and section editors wish to thank Dr. Aviva Must (Tufts University) for providing critical feedback on the content of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Gary Sacks is an academic partner on a healthy supermarket intervention trial that includes Australian local government and supermarket retail (IGA) collaborators. In 2018, he led a study to benchmark the policies and commitments of food companies related to obesity prevention and nutrition.

Ella Robinson declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on The Obesity Epidemic: Causes and Consequences

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sacks, G., Robinson, E. Investing for Health: Potential Mechanisms for the Investment Community to Contribute to Obesity Prevention and Improved Nutrition. Curr Obes Rep 7, 211–219 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-018-0314-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-018-0314-y