Abstract

This study sheds light on the development of family structures in a polygamous context with a particular emphasis on wife order, and offers an explanation for the association between outcomes of children and the status of their mothers among wives based on observable maternal characteristics. In a simple framework, I propose that selection into rank among wives with respect to female productivity takes place: highly productive women are more strongly demanded in the marriage market than less productive women, giving them a higher chance of becoming first wives. Furthermore, productivity is positively associated with a wife’s bargained share of family income to be spent on consumption and investment for herself and her offspring because of greater contributions to family income and larger outside options. The findings are empirically supported by a positive relationship between indicators of female productivity and women’s levels of seniority among wives, and by a concise replication of existing evidence relating wife order to children’s educational outcomes in household survey data from rural Ethiopia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Polygamy is a prominent feature of many societies in the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa, and previous research has indicated that the status of a mother among wives in polygamous families influences the outcomes of her children, with children of first (senior) wives faring better than children of subsequent (junior) wives (e.g., Gibson and Mace 2007; Mammen 2009; Strauss 1990).Footnote 1 Although the existing explanation for this phenomenon is grounded on differences in bargaining power, this study outlines a framework offering a complementary explanation for the differences in the shares of family income controlled by polygamous wives that is based on observable female characteristics.Footnote 2 In particular, this study contributes to the literature on polygamy by proposing a mechanism through which the position among wives affects female-controlled shares of family income: I suggest that both the position among wives as well as incomes when married are determined by a woman’s productivity—that is, the net present value of her future contributions to family income. This, in turn, limits the role of wife order per se as the source of differences in family income controlled by wives.

In a simple game theoretical framework with two types of women, I suggest that women are selected into rank depending on their productivity: in polygamous marriages, high-productivity women are more likely to become first wives than low-productivity women because of the higher utility gains for the husband. Rank relates purely to the sequence of wives entering the household in this study and the same applies when referring to seniority among wives. First (senior) wives are therefore women who marry a single man, and all subsequent women entering the household through marriage to an already married man are collectively referred to as junior wives.

Productivity, a general measure of the lifetime ability to generate income, is positively associated with a wife’s contribution to family production through the provision of labor by herself or her children. Productivity may therefore be thought of as the sum of her future contributions to family income. Determining shares of controlled family income on the basis of a Nash bargaining solution implies that high-productivity wives receive bigger shares of family income irrespective of rank, even when bargaining power is equal for all agents, because of their higher contributions to family output and their larger outside options. These findings offer an explanation for first wives, who are, on average, relatively more productive, receiving larger incomes for their maternal nuclear families than junior wives.Footnote 3 It is therefore not merely different levels of bargaining power associated with rank or some form of favoritism originating from the husband toward his first wife that drive differences in the incomes of wives of a given man.

Munro et al. (2010), on the other hand, found that, if the husband allocates the proceeds from an investment in an experimental setting in Northern Nigeria, senior wives receive higher returns than junior wives. Although this behavior may be evidence of favoritism, it may also be seen as the husband taking into account bargaining processes taking place outside the frame of the experiment, particularly because not all of the husband’s allocations are made in secrecy. If favoritism does exist and influence the shares of income that a wife controls, however, both the explanations based on bargaining power and favoritism work in the same direction as the mechanism grounded on female productivity and proposed here; favoritism may, therefore, enhance the suggested mechanism. To isolate the role of female characteristics, favoritism is disregarded for the remainder of the study, however.

The rationale behind the relationship between a woman’s productivity, the share of family income that she controls, and her children’s outcomes is as follows: if parents depend on their children for support at a later age, the larger a woman’s number of children and the higher their incomes, the higher her future income (Cunningham et al. 2013). Therefore, it is reasonable for polygamous wives not to pool resources across all children of the household head but instead to try to attract the biggest possible share of total family income to invest in their own children (Mammen 2009). Such logic relates to a study by Kazianga and Wahhaj (2015), who found evidence suggesting that members of nuclear families have stronger ties and allocate resources more efficiently than members of extended families because of the possibility of committing to more efficient contracts. Furthermore, according to Friedman’s (1957) permanent income hypothesis, women maximize future income (utility) if they behave like rational agents. Consequently, women invest in their children not purely for altruistic reasons, and children of mothers with higher incomes have better outcomes. Similarly, see Pitt and Khandker (1998) and Qian (2008), who provided evidence of the positive relationship between female incomes and educational outcomes of children, especially girls.

I provide empirical support for the theoretical predictions of this study with household survey data on polygamous families in rural Ethiopia, mainly among the ethnic group of the Oromo.Footnote 4 Tertilt (2005) stated that less than 10 % of all marriages in Ethiopia are polygamous, but approximately one-third of married Oromo women are in a marital union with a man who has more than one wife. Polygamy is highly prestigious for men, and research has reported that resources are shared among wives in recognition of maternal nuclear family size (Gibson and Mace 2007).

In the upcoming empirical section of this article, parental wealth and the age of women (both at the time of the wedding) serve as indicators of female productivity. I find that first wives have wealthier family backgrounds and are younger at the time of the wedding than junior wives. This finding supports the proposition that high-productivity women are more likely to become first wives and that there is a selection effect that leads these women to be successful in the marriage market earlier in life. Furthermore, the maternal nuclear families of first wives attract a bigger share of family income, which is reflected in higher school attendance among children of first wives than among those of junior wives. The data do not provide any evidence that this finding is driven by children of senior wives being more likely to be enrolled in school, however.

Although some work has investigated the incidence of polygamy (e.g., Becker 1974, 1981), no studies exist on the development of wife order to the best of my knowledge. Furthermore, with male inequality often being presented as one of the prominent reasons for polygamy (e.g., Fenske 2015; Hames 1996; Murdock 1949), a strand of the literature has also looked at the implications of women’s productivity on the existence and intensity of polygamous unions (Gould et al. 2008; Jacoby 1995). The relationship between productivity and the share of total family income that a wife receives appears not to have been addressed thus far—a gap that this study attempts to contribute to closing. However, the focus of this investigation is the development of wife order within polygamous unions, not the incidence of polygamy itself.

Jacoby (1995) linked female productivity in agriculture to the incidence of polygamy and found that men have more wives when women are more productive, controlling for men’s wealth, because of lower shadow prices for wives as cheap labor. Jacoby assumed, however, that there are no productivity premiums on the share of family income that a wife receives. Gould et al. (2008) investigated why developed economies tend to practice monogamy in contrast to developing countries, arguing that inequality in female human capital increases with development and reduces the incidence of polygamy. Similar to Jacoby (1995), Gould et al. assumed that there are no differences in the returns of wives of a given husband. Ezeh (1997) specifically studied the interplay of polygyny and reproductive behavior, finding that high regional intensity of polygamy goes hand in hand with high aggregate fertility.

The selection effect proposed in the framework of this study is in line with Gibson and Mace (2007), who merely suggested that senior wives may be of higher quality than junior wives, where quality relates to factors such as wealth, family status, or attractiveness. Furthermore, empirical evidence has shown that differences exist in the incomes of wives depending on their relative position, which serves as the motivation for this article. Gibson and Mace (2007) found that senior wives tend to have the highest body mass index (BMI) among wives, and Kazianga and Klonner (2009) suggested that junior wives are at a significant material disadvantage. Strassman (1997), on the other hand, showed that first wives among the Dogon in Mali generally have a higher social status but only nonmaterial advantages compared with junior wives.

Gibson and Mace (2007) gave an overview of the not entirely conclusive literature on the implications of maternal rank among wives for children. A common finding, however, is that children of first wives have better educational outcomes than children of junior wives (Gibson and Mace 2007). Mammen (2009) found that being the child of a senior wife is positively related to school enrollment and expenditures, and to the duration of education. In addition, children of junior wives are found to be more likely to participate in home production (Mammen 2009). Furthermore, Gibson and Mace (2007); Strauss (1990), and Strauss and Mehra (1990) presented evidence that children of junior wives fare worse with respect to anthropometric conditions and survival probability.

Mammen (2009) argued that rank itself could be the source of different levels of income by influencing bargaining power among wives when competing for resources, and Kazianga and Klonner (2009) stated that junior wives are generally the adults with the least bargaining power in polygamous families. While the concept of bargaining power is difficult to quantify, the present study suggests that a woman’s high level of productivity both gives her a better chance of becoming a first wife and earns her a higher income within the family, thereby presenting an explanation for the association between seniority among wives and income, and eroding the effect of rank per se. Productivity is likely to positively impact bargaining power, too, but this aspect is beyond the scope of this study; thus, differences in bargaining power are ignored for the purpose of an analysis of the role of productivity in the determination of income shares attracted within the family.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. First, I develop the simple framework demonstrating the proposed selection of women into rank on the basis of productivity and the association between productivity and income. I then describe the data and the empirical evidence examining the correlates of wife order in the present sample. Finally, I offer conclusions.

The Framework

This section presents a simple framework using Becker’s (1981) model of polygamy as a starting point but allowing for women to differ in productivity and for productivity to influence partner choice. I illustrate the proposed selection effect of women into rank depending on their productivity and the positive relationship between productivity and the shares of family output wives control. Note that I do not present a formal theoretical model but rather a formal illustration of the proposed mechanism. To this end, assumptions are generally supported by evidence from the existing literature because they play a critical role in shaping the design of the framework.

To offer a nontechnical summary of the framework, men are allowed to have up to two wives, women can be married to only one man, spouses individually and jointly generate family output where men evenly divide their resources between wives, and output is shared between spouses in recognition of their abilities to generate income when single. Because women who contribute more to family income lead to larger returns for men, they are preferred by men, enter marriage first, and therefore have a larger chance of becoming first wives than women who are able to contribute less to family income. Finally, the larger contribution to family income also leads to greater controlled shares of family income for women with larger earning potential compared with women who are less economically successful, which illustrates why first wives are generally found to control a larger share of family income than junior ones. Rank is not critical in itself for this to happen, but the ability to contribute to family income is a determinant of both the position among wives and the controlled share of family income. This study’s framework, thus, presents a structured description of the mechanism through which wife order appears to influence female-controlled shares of family income and, in turn, weakens the relationship between female income and rank per se.

Productivity of individuals at the time of the wedding relates to the ability to generate income, either directly through employment and insurance possibilities provided by their parents, or indirectly through the provision of a large number of children. I define productivity as the net present value of an individual’s future contributions to family income. Children are important for family income because they support the family by performing agricultural work on the family’s land and with livestock during childhood, and by providing an old-age pension equivalent when parents are too old to work. Consequently, highly productive individuals are younger, healthier, better educated, and of higher fertility.

Setup

Consider an economy in which F women are born per generation, of whom a fraction are high-productivity women and the remainder are of low productivity, all else being equal.Footnote 5 In addition, each generation is assumed to have N identical men in order to focus the analysis on the implications of differences in female productivity on wife order within polygamous societies, rather than on the incidence of polygamy to begin with. As mentioned in the Introduction, male inequality is one of the main reasons for the incidence of polygamy (see, e.g., Fenske 2015; Hames 1996; Murdock 1949).

Individuals live for two time periods, and the number of weddings is restricted to one per period and individual. Men may therefore be married to at most two women. Women can enter marriage with only one partner. Furthermore, generations marry only among themselves. All individuals are of reproductive age and are single at the beginning of the first period. There is full information: that is, the productivity of potential spouses is observable, and payoffs are common knowledge. Productivity may, for example, be observed through a healthy and strong physique that acts as an indicator of the individual’s ability to perform agricultural work and reproduce successfully, as well as through parental wealth that positively impacts an individual’s education and physical health—and, thus, fertility and the ability to generate income.

Family Output

Drawing conclusions about the decisions of spouses regarding marriage requires determining their payoffs from entering a marital union. Because co-wives do not pool resources but live autonomously with their children, the husband’s production with each wife is independent.Footnote 6 Total family utility U is the sum of the outputs Y produced by a husband with each of his wives, as suggested by Becker (1981):

where \( \overline{w} \) and \( \underline{w} \) denote the number of high- and low-productivity wives of a husband, respectively. In this setup, \( \overline{w}+\underline{w}\le 2 \) because of the restrictions on marriages per individual and period. Furthermore, for family output U to be positive, \( \overline{w}+\underline{w}>0 \) needs to hold.

\( \overline{Y} \) denotes the production of a husband with a highly productive spouse, and \( \underline{Y} \)represents his output with a low-productivity wife.Footnote 7 Men and women are endowed with x N and x F , respectively, and each man and woman supplies one unit of labor. The production functions n and f describe how the spouses individually convert their endowments into processed resources—for example, into their own labor force to contribute to joint output or into individual output. Function f increases and is concave in female productivity; thus, \( \overline{f}\left({x}_F\right)>\underline{f}\left({x}_F\right) \). The resources available to high- and low-productivity women, x F , and the share of processed resources invested by the husband with each wife, \( n\left({x}_N\right)/\overline{w}+\underline{w} \), are identical across types.

Function j describes the joint efforts of a husband-wife match to convert their individually processed resources into joint output Y. The joint production of a husband and wife exceeds the sum of their individual products—that is, Y j ′ > 0—with both types of women, but the function exhibits concavity. The joint production function increases and is concave in female productivity; thus, \( \overline{j}>\underline{j} \) for equal endowments and productivity in individual production. This implies that the excess product of spouses is larger with a high-productivity wife than with a low-productivity wife. Examples of the surplus over the sum of the individual products include procreation for which an investment of both the husband and wife is needed, or the utility gained from labor sharing or specialization of spouses in agricultural work.Footnote 8 It is common for some plots of the family to be managed and farmed by the male spouse and others to be managed by the female spouse (Udry et al. 1995). In addition, some crops are gender-specific, so that a marital union results in the household producing a larger number of crops, which is also the case in Ethiopia (Aregu et al. 2011). This strategy allows risk diversification, especially because cash crops tend to be male crops, whereas women engage in subsistence farming (Elson 1995).

Male Income When Married

Both men and women have a choice: marrying or staying single. In both periods, they enter a marital union if they gain more utility from being married than from being single. Returns from marriage depend on the couple’s joint production Y. Spouses determine each other’s shares Z Ni and Z Fi of joint output Y i for the husband and wife, respectively, according to a Nash bargaining solution by taking into account their incomes when not entering marriage as well as their spouse’s reaction.Footnote 9 Whether the marriage is the first or second for the husband is denoted by i = 1, 2, no temporal subscript is necessary for spouses because women can enter only one marriage. The incomes when not entering marriage are denoted by R Ni and R F and represent the outside options of the man and woman—that is, their incomes if they fail to reach an agreement—and are positive functions of x N and x F , respectively. Nash bargaining splits the surplus that marriage yields over and above the sum of the outside options R Ni + R F . In case of a marriage between a man and a highly productive woman, for example, the spouses determine the Nash bargaining solution by maximizing the product of excess utilities over the husband’s share \( {\overline{Z}}_{Ni} \):

where \( {\overline{Z}}_{Fi}={\overline{Y}}_i-{\overline{Z}}_{Ni} \) and Z is the set of possible payoffs from marriage. All agents have equal bargaining power of 1/2 in order to isolate the effect of female productivity without possible noise originating from different levels of bargaining power.Footnote 10 Consequently, the gain generated by marriage—that is, the surplus over the incomes when single—is shared equally. Consider the first marital union of a man—that is, where i = 1. Maximization of Eq. (2) with respect to \( {\overline{Z}}_{N1} \) and subsequently solving for the woman’s income when married, \( {\overline{Z}}_{F1} \), yields the returns from marriage between a man and a high-productivity woman:

The payoffs from marriage with a low-productivity wife are determined analogously. Equations (3) and (4) show that the share of the couple’s output a spouse receives increases with her outside option, \( {Z}_R^{\mathit{\prime}}>0 \). Because of limited opportunities for unmarried women to earn income in sub-Saharan Africa, their outside options are smaller than those of men, \( {\underline{R}}_F<{\overline{R}}_F<{R}_{Ni} \), and the husband receives a larger share of family income. Furthermore, women’s reservation wages are partly determined endogenously, which ensures that all women have a chance of entering marriage.Footnote 11 However, incomes of all agents, when single, are greater than zero.

Both spouses have higher incomes when married than when single because of the complementarities of male and female labor, \( {Y}_j^{\mathit{\prime}}>0 \), which leads to the couple’s output being bigger than the sum of the individual outputs; that is, Y 1 > R N1 + R F , irrespective of the wife being of high or low productivity. Accordingly, all agents strictly prefer marriage over being single. Equations (3) and (4) indicate that each agent receives an equal share of the surplus in addition to her outside option because of equal bargaining power.

The fractions of family income \( {\overline{z}}_{N1}={\overline{Z}}_{N1}/{\overline{Y}}_1 \) and \( \left(1-{\overline{z}}_{N1}\right)={\overline{Z}}_{F1}/{\overline{Y}}_1 \) corresponding to Eqs. (3) and (4) are given by

and analogously for marriages involving a low-productivity wife. Equations (5) and (6) indicate that the share each spouse receives depends on the relative size of her reservation wage. Given that male outside options are larger than female ones, \( {R}_{N1}>{\overline{R}}_F \), husbands receive more than one-half of the joint output; that is, \( {z}_{N1}>\frac{1}{2} \). Furthermore, because high-productivity women have higher incomes when single than do low-productivity women, \( {\overline{R}}_F>{\underline{R}}_F \), husbands receive a smaller fraction of joint output when married to a high-productivity wife than to a low-productivity wife; that is, \( {\overline{z}}_{N1}<{\underline{z}}_{N1} \). However, the relation between the absolute shares that he receives, \( {\overline{Z}}_{N1} \) and \( {\underline{Z}}_{N1} \), also depends on the couple’s joint output Y 1 because the latter is higher with a high-productivity wife than with a low-productivity wife; that is, \( {\overline{Y}}_1>{\underline{Y}}_1 \). Because the marginal product of marriage is positive, \( {Y}_j^{\mathit{\prime}}>0 \), and because the joint productivity function increases with female productivity, the difference in joint output is bigger than the difference in incomes when single when comparing the two types of wives:

Because the male outside option R N1 remains unaffected, it follows that a man’s payoff from marriage Z N1 is higher when married to a high-productivity wife as he attracts one-half of the surplus:

Because of the positive marginal product from each marriage, \( {Y}_j^{\mathit{\prime}}>0 \), male income always increases with marriage. However, because male effective resources and individual output invested with each wife n(x N ) are divided by the total number of wives \( \overline{w}+\underline{w} \), the marginal product decreases, \( {Y}_j^{\mathit{{\prime\prime}}}<0 \), and men experience diminishing returns to marriage. For the same reason, a first wife’s income when married decreases when her husband enters marriage with a second woman, so women prefer monogamy. This does not impact a woman’s decision to marry when men are identical, however, because she is not able to anticipate whether he enters marriage in the second period.Footnote 12

The fact that a man’s reservation wages when he is already married are equal to the returns from his first marriage and not to his income when single—that is, R N2 = Z N1 > R N1—influences the returns of each spouse entering his second marriage. It is apparent that he receives a bigger fraction of joint output in his second marriage, z N2 > z N1, holding the type of wife constant. Women, therefore, prefer being the first wife if they are in a polygamous union. Furthermore, given that \( {\overline{Z}}_{N1}>{\underline{Z}}_{N1} \), if a woman only has the option of becoming a second wife, she would prefer having a low-productivity co-wife, which would enable her to extract a larger share of the couple’s joint output.Footnote 13

Following Eq. (8), marrying a high-productivity woman is preferred over entering marriage with a low-productivity woman due to higher male returns, irrespective of which marriage it is for the man.

The Matching Process

The matching of spouses is a crucial part of demonstrating the selection of women into rank. In each period, there are three potential agents: a man, a high-productivity woman, and a low-productivity woman. The husband and wife are not necessarily the decision-makers with regard to partner choice given that their families may play an influential role, especially when individuals marry at a very young age (Carmichael 2011) and for first marriages with and of the senior wife.Footnote 14 However, whether it is the spouses themselves or their families who decide on the partner does not alter the behavior in the marriage market if partner choice is based on rational considerations—that is, on maximizing individual utility—and if parents’ utility increases with their child’s income.Footnote 15

To make the model more realistic, I introduce rationing of mates and assume there are fewer men than women.Footnote 16 In addition, the number of women does not exceed twice the number of men (to ensure that all women may get married):

Assumption 1. N < F ≤ 2N.

Furthermore, let us assume for the moment that there are fewer high-productivity women than men:Footnote 17

Assumption 2. \( \overline{F}<N \) .

Preferences for marriage of all agents and male preferences for highly productive wives form the basis of the following proposition:

-

Proposition 1:

The more productive wives are, the higher their rank.

Because men are assumed to be identical and because their incomes when married increase with female productivity—that is, \( {\overline{Z}}_{Ni}>{\underline{Z}}_{Ni} \)—all high-productivity women get married in the first period and randomize among potential husbands. Those men that are not matched to a highly productive woman marry a low-productivity woman due to marriage always being more profitable than remaining single; thus, all men are in a marital union at the beginning of the second period. Furthermore, given that the marginal product of marriage is positive, \( {Y}_j^{\mathit{\prime}}>0 \), and that the man extracts part of this surplus, all men prefer entering a second marriage over being monogamous. Because of Assumption 2 (\( \overline{F}<N \)), all high-productivity women as well as some low-productivity women become first wives, and the remaining low-productivity women become second wives, therefore giving substance to Proposition 1.

To be specific, the chance of attracting a highly productive woman in the first round, \( {\overline{m}}_{N1} \), is identical among men. The chance that a man will enter marriage in period 1 in this setting is m N1 = 1 given that women prefer marriage over being single and that men are identical. The chance of entering marriage can be disaggregated into the chances of attracting a highly productive woman in the first period, \( {\overline{m}}_{N1}=\overline{F}/N \), and of being matched to a low-productivity woman, \( {\underline{m}}_{N1}=\left(N-\overline{F}\right)/N \). Male reservation wages when negotiating payoffs of the second marriage are \( {\overline{Z}}_{N1} \)or \( {\underline{Z}}_{N1} \), depending on the type of first wife. For a man married to a high-productivity first wife to have equally good chances of entering a second marriage, m N2 , he negotiates with potential wives with the lower male reservation wage, \( {\underline{Z}}_{N1} \); thus, the type of co-wife is of no importance to a potential second wife. This implies that matching in different periods is independent because the type of first wife has no influence on male marital outcomes in the second period. The process therefore exhibits uniform random matching as described by La Ferrara (2003), and the remaining low-productivity women are matched randomly to their husbands in period 2. To be specific, the chance that a male will enter marriage in period 2 is \( {m}_{N2}={\underline{m}}_{N2}=\left(F-N\right)/N \).

Female Incomes When Married

-

Proposition 2:

The more productive women are, the higher their incomes when married.

Equation (6) illustrates that the fraction of joint output earned by a high-productivity wife is higher than that earned by a low-productivity wife, \( \left(1-{\overline{z}}_{Ni}\right)>\left(1-{\underline{z}}_{Ni}\right) \). Because the man’s outside option, R Ni , does not change with the type of wife for a given i and because joint output is higher the higher female productivity, \( {\overline{Y}}_i>{\underline{Y}}_i \), high-productivity wives have more of family income to control than low-productivity wives:

The conclusions from Eq. (9) hold for women of equal rank. Given that women have a lower threat point relative to the man if he is already married, women of identical productivity but lower rank earn lower incomes from marriage, which means that the direct effect of rank on female income is only weakened and not completely eroded by the present framework—that is, the observed effect of junior wives receiving a smaller share of family income on average is driven by differences in productivity and the associated selection into rank—but there is also a direct effect of rank on controlled income shares that works in the same direction. Furthermore, although the size of the maternal nuclear family is not explicitly incorporated in Eq. (9), the number of children positively influences the returns from marriage for both spouses as children are part of joint output Y, which is in accordance with Gibson and Mace (2007).

Empirical Evidence

In this section, I supply empirical evidence for Propositions 1 and 2: to be specific, I provide empirical support for the proposed selection effect of women into rank and, to some extent, for the association with the shares of family income that polygamous wives receive. The results should be interpreted with care and seen in conjunction with the framework outlined earlier herein, given the limited sample size and the difficulty of accurately measuring key concepts of the framework, such as female productivity, in a setting like rural Ethiopia.

Data

The data employed in this study are the first four rounds of the Ethiopian Rural Household Survey conducted by the Economics Department of Addis Ababa University in collaboration with the International Food Policy Research Institute and the Centre for the Study of African Economies at Oxford University. The surveys have sample sizes of approximately 2,000 households per round. The first round of the survey was conducted between January and March 1994; the second round was conducted in August through October 1994; and the third round was conducted in the first three months of 1995. The fourth round was conducted in 1997, and three additional rounds have been completed since. The main source of data for this study is the fourth round of the survey.Footnote 18

The households surveyed in the different rounds form a panel, but only polygamous households are investigated here, resulting in relatively small sample sizes. The questionnaires are very detailed, especially in the fourth round, which contains an extensive section on the marital history of the household head and his spouse(s). Furthermore, the information about both spouses and the circumstances at the time of the wedding is unique in household surveys to the best of my knowledge and essential in order to give empirical evidence in support of the propositions formulated earlier. The survey includes questions about the timing of each wedding, the decision-maker regarding partner choice, the family background of each spouse, and the biological parents of each child.Footnote 19 The fact that this data set is unique in exhibiting characteristics and containing information that are essential for an investigation of wife order following the framework presented in the previous section is the motivation for conducting the empirical investigation with data from Ethiopia, even though it is a country with a rather rare incidence of polygamy.

In cases where the data on the timing of the wedding suffer from measurement error, I use the panel structure of the dataset to establish the sequence of wives of the household head entering the family between Rounds 1 and 4.Footnote 20 These procedures enable nonambiguous ranking of 85 % of the wives in the sample. For the minority of wives for whom the sequence of weddings is not clear after these steps, I apply the method suggested by Mammen (2009) and Elbedour et al. (2002) and proxy the order of wives by their age, with rank being positively related to age. Thus, the oldest woman is regarded as the senior wife, the second oldest is considered the second wife, and so on. This strategy is not ideal given that junior wives can be older than senior wives, especially if the age difference is small. In most cases, however, this negative correlation between rank and age holds, as verified by those households in the sample for which the sequence of weddings is known: for 83 % of the wives for whom the ranking is clear, age predicts marital sequence correctly. In addition, using this strategy is necessary for only 15 % of wives in the sample, thus ameliorating this concern.Footnote 21

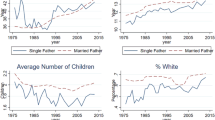

Table 1 presents summary statistics for polygamous wives and mean-comparison tests between first and second wives.Footnote 22 First wives married their current husband at a younger age and have been married considerably longer than junior wives.Footnote 23 Both differences are statistically significant. The fact that first wives have been married longer is true by definition: first wives are obviously those women who marry a man first. However, the vast difference in the duration of marriage, especially between first and second wives, is noteworthy and indicates that the decision to move from a monogamous to a polygamous marriage takes longer than the decision to move from having two wives to three, for example. The finding that first wives are considerably younger upon marriage supports Proposition 1: young age at the time of the wedding is associated with higher productivity; first wives are highly demanded and exit the marriage market earlier in life.

The variables parents poor, parents of average wealth, and parents rich are indicator variables for how wealthy the husband perceived his bride’s parents to be at the time of the wedding.Footnote 24 The parents of first wives appear to have been perceived to be a little wealthier by the husband at the time of the wedding, which would be expected following the framework in the previous section, but a clear trend is not apparent. Furthermore, the differences between first and second wives are not statistically significant.

Table 1 also shows that first wives have a larger total number of children from the current marital union and more children of schooling age (between ages 6 and 18, both inclusive). This finding is expected given that fertility is part of the general concept of female productivity discussed earlier. Both differences are statistically significant.

When assessing fertility of wives, however, note that some women—and especially first wives—marry at very young ages, when they may not yet be able to conceive.Footnote 25 On the other hand, as shown in Table 1, first wives tend to marry at a considerably younger age than junior wives, which also means that they have more reproductive years with their husbands. To ensure that differences in fertility in relation to the duration of the marriage are not driven by the fact that wives are married at an age when they may not be able to conceive yet or cannot conceive anymore, I do not take into account the years of marriage in which a wife was not of reproductive age when I compute the relative number of children. The relative number of children therefore denotes the number of children of a wife and her husband divided by the number of years they have been married while she was of reproductive age. Women are considered to be of reproductive age between ages 15 and 49, in line with the United Nations (2004) and Yohannes et al. (2011), the latter of which specifically investigated Ethiopian data. Inclusion of the years in which a wife was not of reproductive age does not qualitatively alter the main results, however.

The difference in fertility in relation to the duration of marriage at reproductive age is statistically significant and shows that productivity in terms of fertility is not higher among senior wives, which may appear to be a contrast to the mechanism proposed in this article. However, female productivity, as described in the framework, relates to reproductive potential, not to realized fertility, which is subject to characteristics of the relationship other than female reproductive potential.

In summary, the data support the prediction that first wives get married at a younger age than junior wives. No conclusive picture to support Proposition 1 emerges when looking at realized fertility or the natal family’s background in terms of wealth, however. Descriptive statistics for the households in which the polygamous wives in this sample live are given in Table 3 in Appendix 2.

Correlates of Rank

Supporting Proposition 1 with empirical evidence is difficult because productivity cannot be directly measured, especially in a setting like rural Ethiopia. If women were in paid employment, their earnings could serve as a proxy for human capital. Alternatively, if data were available on the returns to agricultural activity for each household member or if reproductive potential rather than realized fertility could be measured, two central aspects of the concept of female productivity described in the framework could be captured empirically. The most accurate indicators of a woman’s human capital available here are her natal family’s background and her age at the time of the wedding. These measures are not ideal, but they proxy female productivity for the following reasons: a wealthy family background is likely to increase the chances of a relatively good education, of a strong and healthy physique that is positively correlated with the ability of giving birth to many healthy children, and of relatively high contributions to family income. The last two reasons are, furthermore, likely to be fostered by young age.

Specification

To explore whether rank among wives correlates with characteristics that are indicative of a woman’s productivity in the present sample, I estimate the following relationship:

where subscript i denotes the observational unit—that is, a polygamously married woman, living in household h in woreda (district) w. First wife is a binary variable that takes a value of 1 if the woman is the senior wife and 0 otherwise (if she is a second or even more junior wife).Footnote 26 Because the dependent variable is binary, I estimate a probit model with heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors.

I control for the wealth of the bride’s parents at the time of the wedding by including indicator variables for the parents having been of average wealth or rich, with parents poor being the reference category. Other key explanatory variables are the wife’s age at the time of the wedding to her current husband and the number of children from the union of this wife and her husband divided by the number of married years during which the wife was of reproductive age (as explained in the earlier data description).Footnote 27 X is a vector of individual controls, including whether the woman was consulted regarding the choice of her husband, how many years she has been married to her current husband, and her BMI. In many developing countries, a high BMI is still considered a signaling device for health and material well-being. Unfortunately, a woman’s BMI can be observed only at the time of the survey; no information is available for her BMI at the time of the wedding. The BMI at the time of the survey may be correlated with her BMI at the time of the wedding, but it is more likely to be an indication of her consumption and therefore her controlled share of family income.

H is a vector of household controls, including the logarithmic value of the total values of assets, the total size of the household’s land holdings, and livestock. Although all these are characteristics of the wife’s current household and therefore do not help in explaining wife order, their inclusion is necessary in this specification to ensure that differences between households are not driving the results. (The possibility of specifically investigating differences within, rather than between, households is discussed shortly.) The values of assets and livestock are given in Ethiopian Birr; the size of land holdings is measured in hectares. Another household control is the average quality of the land, which is measured by the mean of a binary variable taking a value of 1 if the respondent rates a plot as lem (good) and a value of 0 if it is regarded as lem-teuf (medium) or teuf (poor), averaged over all plots of the household. W consists of indicator variables for the district in which a household resides.Footnote 28

Results

The marginal effects for the specification outlined in Eq. (10) are given in Table 2; the estimated coefficients are presented in Table 4 in Appendix 2. The estimation technique is identical in columns 1– 4, but the control variables differ. The results given in Tables 2 and 4 (the latter of which is in Appendix 2) suggest that some characteristics of a woman that indicate high productivity are statistically significantly correlated with becoming the senior wife.Footnote 29 The coefficient on whether the parents of the bride were of average wealth at the time of the wedding does not yield a statistically significant coefficient in the majority of columns, but the variable indicating that the parents of the bride were perceived to be rich does in all columns. This finding suggests that if the woman’s natal family is perceived to be relatively wealthy, she is more likely to be a first wife. Specifically, a woman’s chance of being a first wife increases by 36.3 % to 62.4 % if, at the time of the wedding, the husband perceived her parents to be rich in comparison with perceiving them as being poor. Wealth is often strongly and positively associated with prestige and respect, and marrying a woman from such a family could be a desirable strategy to enhance one’s prestige within the community. Furthermore, women growing up in wealthy families may be of better nutritional and educational status, which in turn suggests more and possibly healthier offspring. Another explanation for this significant association is an insurance effect: a man would want to marry a woman from a wealthy family first so that a strong family network is present to support in needy times.Footnote 30

The coefficient on the wife’s age at the time of the wedding is statistically significant and negative, which indicates that single older women are less likely to become senior wives. Each additional year of age at the time of the wedding is associated with a 2.9 % to 4.5 % lower probability of becoming a first wife, as shown in Table 2. Two mechanisms are likely to be at work here. First, younger women are considered to be of higher productivity and quality, possibly when thinking of the expected number of children, her attractiveness, or her ability to perform agricultural work. Second, senior wives are selected for marriage at a younger age than junior wives. The first mechanism supports the idea of a qualitative selection effect in which high-productivity women are more likely to become first wives, while the latter supports the idea of a temporal selection into marital rank in which high-productivity women are demanded more strongly in the marriage market and therefore marry earlier in life.

The relative number of children is negatively but statistically insignificantly related to becoming a senior wife. This may, however, not necessarily be the result of a wife’s reproductive potential but rather of the amount of time that the husband spends with her. Gibson and Mace (2007) reported that men pay more attention to junior wives, which is likely to increase their chances of conceiving. Another explanation is that men often choose to marry another wife because their first wife’s fertility does not meet their expectations (Kazianga and Klonner 2009). In either case, the number of children in relation to the duration of the union is an ex post measure of the couple’s joint reproductive potential and activities as opposed to the ex ante measure of female reproductive potential incorporated into the framework as a central aspect of a woman’s productivity. Determining a woman’s fertility at the time of the wedding is not possible, so the relative number of children is used as a proxy for fertility here.

Whether a woman was consulted regarding the choice of her husband is not statistically significantly associated with being the first wife. Neither is a woman’s current BMI, which is a contrast to the findings of Gibson and Mace (2007), suggesting that first wives do not have nutritional advantages over junior wives.

Because first wives, by definition, are the wives that have been married to a man longest, the coefficient on the duration of the current marriage is positive and statistically significant. This variable should be viewed as a classical control variable that is included to single out the effect of age at marriage from time effects. If the duration of the marriage were not controlled for, it would not be possible to rule out that first wives are younger at the time of the wedding than junior wives because individuals simply prefer to get married at an older age the further time progresses. The inclusion of further household controls in columns 3 and 4 of Table 2 does not qualitatively alter the results.

As a robustness check on the probit model, I use a linear probability model and find support for the general picture emanating from the main results, as displayed in columns 1– 4 of Table 5 in Appendix 2. On another note, it appears most applicable to investigate the determinants of wife order within families of the same husband rather than to investigate differences between households. The inclusion of household fixed effects is not unproblematic, however, because the sample contains women whose co-wives have missing data and are therefore not part of the estimation sample. Nevertheless, the general picture is also supported when household fixed effects are introduced to the linear probability model, as presented in columns 5 and 6 of Table 5 in Appendix 2. Finally, there is reason for concern that the error variances of wives who are married to the same husband may not be independent. The main results are robust to the standard errors being clustered at the household level, as displayed in Tables 6 and 7 in Appendix 2.

Allocation of Resources Among Wives

In this section, I outline a strategy to empirically support Proposition 2, which suggests a positive effect of female productivity on incomes when married through rank. Besides productivity, female income (the share of family income a wife attracts for consumption and investment in her nuclear family) cannot be measured directly. Although Gibson and Mace (2007) reported that each wife in polygamous families among the Oromo holds an independent household budget, neither this household budget nor the consumption of each household member can be quantified with the survey data available.

Empirical evidence suggests a positive relationship between maternal income and children’s outcomes with respect to health (Duflo 2003; Qian 2008) and specifically with respect to educational outcomes (Pitt and Khandker 1998; Qian 2008), however. Investment in children can be measured by whether a child is enrolled in school and, more precisely, by effective school attendance. Thus, I use children’s educational outcomes as indicators of female income here. Although enrollment is associated with sunk costs for school fees and equipment, attending school implies school supply costs and considerable opportunity costs. When not attending school, a child may be working on the family’s land holdings or taking care of the family’s livestock (a traditional responsibility of children in rural Ethiopia). Both the direct and opportunity costs of schooling may be indirectly paid for with the share of family income that the mother controls.

Intuitively, the most appropriate empirical strategy to test the theoretical framework laid out earlier would be a two-stage procedure instrumenting for maternal rank with the proxy variables for female productivity. A violation of the exclusion restriction is likely, however.Footnote 31 Thus, I directly use maternal rank as an indicator of productivity, which appears reasonable given the positive association found in the previous section. Consequently, the evidence on the allocation of resources that may be derived from the data set used here is in fact a replication of the previous findings of a relationship between maternal rank among wives and children’s educational outcomes (Gibson and Mace 2007; Mammen 2009; Strauss 1990). The data used here provide evidence in support of these earlier findings of children exhibiting better educational outcomes if their mothers are first wives instead of junior wives, specifically with respect to school attendance but not with respect to school enrollment. Because this part of the study is a replication of earlier findings and because of the aforementioned methodological difficulties in directly testing this part of the framework, the empirical evidence including a description of the specification and results is not part of the main text; it can be found in Appendix 3.

Conclusions

This study investigates the relationships among a woman’s productivity, her rank among wives, and the share of total family income that she controls in a polygamous family—that is, in a situation where she may not be the only wife of her husband at a given time. Previous research has suggested that first wives may be able to attract a larger proportion of the family’s income because they have higher levels of bargaining power than junior wives (Mammen 2009). This article introduces female productivity to the matching process of spouses and argues that high-productivity women are more likely to become first wives. Furthermore, productivity plays a role in determining a spouse’s returns from marriage. The larger share of family income attracted by senior wives is therefore not merely due to higher bargaining power or favoritism associated with rank, but a wife’s level of seniority among wives and her returns are jointly determined by her productivity. Very possibly, however, productivity positively influences bargaining power, so the explanations are likely to be complementary.

I use a simple framework to illustrate that relatively productive women have a higher chance of becoming a first wife: they select into rank depending on productivity, resulting from a higher utility gain for the husband if he is married to a highly productive woman. Because high-productivity wives contribute more to family production and have higher incomes when single, they receive a larger share of family income through Nash bargaining with their husbands than do low-productivity wives. Thus, the mechanism through which rank influences female income is based on productivity.

The empirical analysis supports these propositions by showing that senior wives have a wealthier family background at the time of the wedding and enter marriage at a younger age than junior wives. On one hand, these findings support the proposed qualitative selection effect: young age at the time of the wedding may be an indicator of productivity because a woman’s reproductive prospects are negatively related to her age. On the other hand, the lower age of senior wives at the time of the wedding also suggests a temporal selection effect: they exit the marriage market first because men prefer marrying a highly productive over a less productive woman. Furthermore, I provide some empirical support for the relationship between wife order and female income: children of senior wives are at an advantage regarding school attendance compared with children of junior wives.

The study therefore suggests that polygamous households should not be treated as a uniform family but as a collection of nuclear families consisting of the household head, a wife, and their joint children. Consequently, for aid programs and development policy aiming to increase school attendance in regions that exhibit polygamy, the target unit should be the maternal nuclear family and special attention should be paid to children of junior wives.

Notes

Tertilt (2005) stated that more than 10 % of marriages in 28 countries of sub-Saharan Africa are polygamous and that more than one-half of males in Cameroon are married to more than one woman, for example. Polygamy is mostly associated with Muslim ethnic groups (Elbedour et al. 2002), and according to the Koran, a man may have a maximum of four wives, whom he has to support and to treat equally (Boserup 1970). This coincides with geographical variation of polygamy and its more common occurrence in the West than in the East of the African continent, which Dalton and Leung (2014) explained with historical patterns of slave trade.

To be precise, this article deals with polygyny, a special form of polygamy in which men are married to more than one woman at a time. Throughout the article, this is what the terms polygamy and polygamous refer to.

In accordance with Uusimaa et al. (2007), a maternal nuclear family denotes a mother and her biological children. In this setting, this term refers exclusively to polygamous wives and their biological children.

The Oromo are a traditionally semi-nomadic pastoralist ethnic group mostly found in the South of the country, and 53 % of the polygamous wives in the present sample state Oromo as their ethnicity. The remainder are Gedeo (18 %), Kembata (6 %), Gamo (5 %), Gurage (4 %), and Other (14 %).

Women may not change type here. This is a reasonable assumption because for partner choice the productivity at the time of the wedding is important, and becoming older or less able to contribute to family income over the course of the marriage is therefore not critical.

Co-wives are reported to live autonomously with little cooperation in many African ethnic groups (Boserup 1970; Kazianga and Klonner 2009), including the Oromo in Ethiopia (Gibson and Mace 2007). Akresh et al. (2016) also reported co-wives to live autonomously with their children in their own nuclear units with little cooperation among co-wives, at least with respect to daily activities. Their findings did provide evidence, however, for co-wives cooperating with each other with respect to cultivating plots in which the household head is not involved. Cooperation between wives, especially when the household head is not involved, is not influential for the selection into rank and therefore is not incorporated in this study.

Bars and underbars denote the concerned variables and functions for high- and low-productivity wives, respectively, throughout this section.

See Becker (1973) for a thorough discussion of the gain generated by marriage.

A noncooperative equilibrium within marriage, as suggested by Lundberg and Pollak (1993), is not considered here.

Productivity is very likely to be positively correlated with bargaining power, thereby reinforcing the effect of productivity on controlled shares of family income. Because of this reinforcement of the effect and the aim of isolating the direct effect of productivity on shares of family income controlled by the different types of spouses, the relationship between productivity and bargaining power is ignored. Were this relationship included, highly productive spouses would receive an even larger share of family income relative to less-productive spouses as a result of both better outside options and higher relative bargaining power. For the same reason, the resources invested by the household head are assumed to be identical across wives. If men allocated their resources efficiently and invested more resources the more productive a wife was, the conclusion of the shares of income being controlled by wives being dependent on productivity would be reinforced, and the effect of productivity would therefore be less obvious.

This assumption is reasonable given that being an unmarried woman is not socially accepted or economically sustainable in many rural settings of developing economies, especially among Muslim ethnic groups in which polygamy mostly occurs (Elbedour et al. 2002).

The probability of a husband attracting a second wife is identical among men and is considered in detail in the following section. Because there are more women than men, as assumed here, and because women’s returns when single are very low, it is not a profitable strategy for women to remain single and marry a single man in the second period given that they risk remaining unmarried in the long run, however. Relaxing the restrictions on the number of periods and the number of wives per husband could make this a profitable strategy, but it also implies that women cannot anticipate the number of co-wives. Again, waiting is not profitable because of the risk of remaining single. Similarly, first wives are not able to demand compensation for their husbands entering a second marital union: negotiation of a compensation before their marriage would leave the woman unmarried in the first period as a result of the surplus of women, and negotiation of more than the controlled share of family income determined earlier is not possible in this setting because her outside option and bargaining power remain identical.

If the fractions of joint output z N1 and therefore (1 − z N1) are not assumed to be fixed for the second period (even though a second marriage lowers joint output Y 1 because of lower male investment), women entering marriage in the first period would also prefer a low-productivity co-wife.

Whereas parents often arrange the first marriage, the second one often occurs as a love marriage. This difference should not play a critical role for the conclusions derived from this section, however. If the second wife were highly productive, she would be likely to have become a first wife of another man, rather than being available as a second wife. Furthermore, if love played a role in granting her a privileged status within the family with respect to the allocation of the family’s resources, the empirical finding motivating this study would not exist.

Fafchamps and Quisumbing (2005) stated that most marriages in Ethiopia are arranged and that economic factors appear to be one of the main determinants of partner choice because of the evidence of assortative matching with respect to wealth and human capital. Payments of bride prices are not directly modeled here but could be included as a separate payment in addition to female income. Because men are identical here, bride prices should reflect female productivity only and therefore should be higher for high-productivity women than for low-productivity women. However, they will not influence the conclusions drawn from the framework (1) if they are smaller than the marginal product of a woman in a marital union so that the incomes of both spouses still increase with marriage, and (2) if the difference in bride prices between different types of women does not exceed the difference in utility derived by the man from marriage, which would go against the motivation of bride prices to begin with. If the difference in bride prices were higher than the difference in male payoffs from marriage, men would prefer low-productivity wives because they would derive more net utility from them, which would conflict with the definition of the two types of women examined here to begin with.

This assumption is reasonable in this setting due to incidences of civil wars in which men constitute the majority of casualties due to their higher exposure to this specific danger and due to men being more likely to leave rural areas in search of employment opportunities. Furthermore, Gibson and Mace (2007) mentioned that women are often forced into polygamous marriages due to a surplus of women in the marriage market, which is also given as a motivation for polygamous marriage by Becker (1973), besides large inequalities among men (Becker 1974).

The implications of relaxing Assumption 2 are discussed in Appendix 1.

See Fafchamps and Quisumbing (2005) for a detailed description of the study area, the sampling strategy, and the survey design of Round 4, particularly regarding the module on the marital history of the household head and his spouse(s).

Unfortunately, the amount of usable data in response to some questions is limited—for example, with respect to the spouses’ educational attainment, which would be an ideal proxy for female productivity as introduced in the framework earlier. Besides the low response rate, one explanation for the fact that there are hardly any usable data on spouses’ education is the rural location of these households, in which most adults have not received any formal education.

Measurement error is apparent if the duration of the marriage and the year of the wedding do not add up to either year in the Ethiopian calendar in which the interviews for the fourth round of the survey were conducted, for example.

The main results are robust to using only the subsample of wives for whom the ranking does not need to be imputed on the basis of age.

Only polygamous wives are included in the sample. As shown in Table 1, the number of third and fourth wives is very small, so the mean-comparison tests are performed between first and second wives only. The fact that there are fewer second than first wives is due to missing/misreported data on variables used in the estimation and observations being dropped for this reason.

The very low minimum ages at marriage need not be cases of misreporting or recording errors. Especially in rural Ethiopia, a promise of a young girl’s parents for her to marry a man in the future may be counted as a “marriage” for the purpose of this question, even if the actual wedding may have only occurred much later.

Parents poor includes cases in which the parents were perceived to be “poor” or “very poor,” and parents rich includes parents that were perceived to be “rich” or “very rich,” given the rare mentioning of either extreme case.

Grouping junior wives is necessary here because of the very limited number of third and fourth wives and in accordance with some of the literature (Mammen 2009; Timæus and Reynar 1998; Strauss and Mehra 1990). To verify that first wives exhibit different characteristics than second wives at the time of the wedding, I replicate Table 2 and Table 4 in Appendix 2 with a subsample in which I exclude wives who are more junior than the second wife. The results (not presented here but available upon request) show that although the loss of observations puts strain on the sample, the results are robust to using this subsample.

Questions on other characteristics of the spouses measuring human capital (such as formal education, farming experience, bride prices, or the value of assets brought into marriage) exhibit drastically low response rates in the present sample and may therefore not be used as explanatory variables.

The results are robust to including region rather than district indicator variables.

Because the sample exclusively consists of polygamously married women, the results for being a junior wife as the dependent variable are simply the mirror image of the ones presented here.

Inclusion of binary variables indicating whether the husband perceived the parents of his spouse to be richer or of equal wealth as his natal family does not qualitatively alter the results. Furthermore, neither variable yields statistically significant coefficients. Results are not presented but are available from the author upon request. This absence of an effect is interesting given the findings of Fafchamps and Quisumbing (2005), who found evidence for assortative matching with the same data set. However, these authors looked at assortative matching in the marriage market with respect to physical and human capital of spouses, rather than of their natal families, and they did not specifically explore polygamous unions—especially not wife order.

For example, the exclusion restriction may be violated as the wealth of the mother’s parents may directly impact a child’s educational outcomes, especially when they are associated with monetary costs. Furthermore, the age of the mother at the time of the wedding may have a direct effect on her children’s educational outcomes rather than solely through the channel of affecting her rank among wives. To be specific, women who marry at a younger age may be more traditional and less educated, or may be more modern, and therefore place less or more emphasis, respectively, on their children’s education than women who marry at a later age.

The results are robust to estimating a linear probability model for school enrollment being the dependent variable.

Birth order, being the sibling of the firstborn or of the first son within the household, and the number of full siblings at school age instead of the total number of children in the household do not exhibit a statistically significant impact on children’s educational outcomes. Results including each of these control variables separately support the main results; these results are not presented but are available from the author upon request.

The results are supported, and I find no evidence for selection into school enrollment in a Heckman selection model, the results of which are not presented because the model is not well-specified.

References

Akresh, R., Chen, J. J., & Moore, C. T. (2016). Altruism, cooperation, and efficiency: Agricultural production in polygynous households. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 64, 661–696.

Aregu, L., Puskur, R., & Bishop-Sambrook, C. (2011, January). The role of gender in crop value chain in Ethiopia. Paper presented at the Gender and Market Oriented Agriculture Workshop, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Nairobi, Kenya: International Livestock Research Institute.

Becker, G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 813–846.

Becker, G. S. (1974). A theory of marriage: Part II. Journal of Political Economy, 82, S11–S26.

Becker, G. S. (1981). A treatise on the family (Enlarged ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Boserup, E. (1970). Woman’s role in economic development. London, UK: Earthscan Publications.

Carmichael, S. (2011). Marriage and power: Age at first marriage and spousal age gap in lesser developed countries. History of the Family, 16, 416–436.

Cunningham, S. A., Yount, K. M., Engelman, M., & Agree, E. (2013). Returns on lifetime investments in children in Egypt. Demography, 50, 699–724.

Dalton, J. T., & Leung, T. C. (2014). Why is polygyny more prevalent in Western Africa? An African slave trade perspective. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 64, 599–632.

Duflo, E. (2003). Grandmothers and granddaughters: Old age pension and intra-household allocation in South Africa. World Bank Economic Review, 17, 1–25.

Elbedour, S., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Caridine, C., & Abu-Saad, H. (2002). The effect of polygamous marital structure on behavioral, emotional, and academic adjustment in children: A comprehensive review of the literature. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5, 255–271.

Elson, D. (1995). Male bias in macro-economics: The case of structural adjustment (2nd ed.). Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Ezeh, A. C. (1997). Polygyny and reproductive behavior in sub-Saharan Africa: A contextual analysis. Demography, 34, 355–368.

Fafchamps, M., & Quisumbing, A. (2005). Marriage, bequests, and assortative matching in Ethiopia. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 53, 347–380.

Fenske, J. (2015). African polygamy: Past and present. Journal of Development Economics, 117, 58–73.

Friedman, M. A. (1957). A theory of the consumption function. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gibson, M. A., & Mace, R. (2007). Polygyny, reproductive success and child health in rural Ethiopia: Why marry a married man? Journal of Biosocial Science, 39, 287–300.

Gould, E. D., Moav, O., & Simhon, A. (2008). The mystery of monogamy. American Economic Review, 98, 333–357.

Hames, R. (1996). Costs and benefits of monogamy and polygyny for Yanomamö women. Ethology and Sociobiology, 17, 181–199.

Jacoby, H. G. (1995). The economics of polygyny in sub-Saharan Africa: Female productivity and the demand for wives in Côte d’Ivoire. Journal of Political Economy, 103, 938–971.

Kazianga, H., & Klonner, S. (2009). The intra-household economics of polygyny: Fertility and child mortality in rural Mali (MPRA Paper No. 12859). Retrieved from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/id/eprint/12859

Kazianga, H., & Wahhaj, Z. (2015, July). Norms of allocation within nuclear and extended-family households. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the meeting of the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association and Western Agricultural Economics Association, San Francisco, CA.

La Ferrara, E. (2003). Kin groups and reciprocity: A model of credit transactions in Ghana. American Economic Review, 93, 1730–1751.

Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. A. (1993). Separate spheres bargaining and the marriage market. Journal of Political Economy, 101, 988–1010.

Mammen, K. (2009). All for one or each for her own: Do polygamous families share and share alike? (Working paper). Retrieved from http://www.qc-econ-bba.org/seminarpapers/3-29-12.pdf

Meekers, D. (1992). The process of marriage in African societies: A multiple indicator approach. Population and Development Review, 18, 61–78.

Munro, A., Kebede, B., Tarazona-Gomez, M., & Verschoor, A. (2010). The lion’s share. An experimental analysis of polygamy in northern Nigeria (GRIPS Discussion Paper No. 10–27). Tokyo, Japan: National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies.

Murdock, G. P. (1949). Social structure. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Pitt, M. M., & Khandker, S. R. (1998). The impact of group-based credit programs on poor households in Bangladesh: Does the gender of participants matter? Journal of Political Economy, 106, 958–996.

Qian, N. (2008). Missing women and the price of tea in China: The effect of sex-specific earnings on sex imbalance. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123, 1251–1285.

Strassman, B. I. (1997). Polygyny as a risk factor for child mortality among the Dogon. Current Anthropology, 38, 688–695.

Strauss, J. (1990). Households, communities, and preschool children’s nutrition outcomes: Evidence from rural Côte d’Ivoire. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 38, 231–261.

Strauss, J., & Mehra, K. (1990). Child anthropometry in Côte d’Ivoire: Estimates from two surveys, 1985 and 1986 (LSMS Working Paper No. 51). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Tertilt, M. (2005). Polygyny, fertility, and savings. Journal of Political Economy, 113, 1341–1370.

Timæus, I. M., & Reynar, A. (1998). Polygynists and their wives in sub-Saharan Africa: An analysis of five Demographic and Health Surveys. Population Studies, 52, 145–162.

Udry, C., Hoddinott, J., Alderman, H., & Haddad, L. (1995). Gender differentials in farm productivity: Implications for household efficiency and agricultural policy. Food Policy, 20, 407–423.

United Nations (2004). World Population Monitoring 2002: Reproductive rights and reproductive health (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.02.XIII.14). New York, NY: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, United Nations.

Uusimaa, J., Moilanen, J. S., Vainionpää, L., Tapanainen, P., Lindholm, P., Nuutinen, M., . . . Majamaa, K. (2007). Prevalence, segregation, and phenotype of the mitochondrial DNA 3243A>G mutation in children. Annals of Neurology, 62, 278–287.

Yohannes, S., Wondafrash, M., Abera, M., & Girma, E. (2011). Duration and determinants of birth interval among women of child bearing age in Southern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 11(38). doi:10.1186/1471-2393-11-38

Acknowledgments

I would particularly like to thank Gaia Narciso for her invaluable and continuous support. Furthermore, I am grateful to Gani Aldashev, Tekie Alemu, Kelly de Bruin, Christian Danne, Benjamin Elsner, Robert Gillanders, Worku Heyru, Matthias Kalkuhl, Eoin McGuirk, Carol Newman, John O’Hagan, Jean-Philippe Platteau, Zeratzion Woldelul, participants of various conferences and workshops, and three anonymous referees for helpful comments. Funding from the Graduate Research Education Programme by the Irish Research Council for the Humanities and Social Sciences and from the Department of Economics at Trinity College Dublin is gratefully acknowledged. All errors are mine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

The Matching Process With More High Productivity Women Than Men

Given that the matching of spouses outlined in the framework involves a random element, consider the selection effect for different proportions of high- and low-productivity women in order to show that the conclusions do not depend on the relative populations of men and women.

This section uses the identical setup as before but drops Assumption 2 (\( \overline{F}<N \)), so there may be more highly productive women than men. Furthermore, let there be some low-productivity women:

Assumption A1. \( N<\overline{F}<F \) .

Male income is higher when he is married than when he is single and is highest with a highly productive wife (i.e., \( {\overline{Z}}_{Ni}>{\underline{Z}}_{Ni}>{R}_{Ni} \)). Therefore, men still aim at having as many wives as possible, with all of them ideally being high-productivity women. This results in all first wives being highly productive women and both the remaining high-productivity women as well as all low-productivity women marrying in the second period. This section therefore changes the distribution of women of each type among first and second wives, but the conclusions remain valid: high-productivity women are more likely to become first wives than are low-productivity women.

Appendix 2

Table 3

Table 4

Table 5

Table 6

Table 7

Appendix 3

Empirical Evidence on the Allocation of Resources Among Wives

ᅟ

Specification

ᅟ