Abstract

Aims

The objective of this study was to describe the clinicopathological details in patients referred to the Gynaecologic Oncology Department with possible ovarian or primary peritoneal cancer where the final diagnosis turned out to be abdominal tuberculosis.

Methodology

Retrospective chart analysis of 23 cases diagnosed with abdominal tuberculosis who were admitted under the Division of Gynaecologic Oncology suspected to have disseminated peritoneal malignancy, during 2014–2017.

Results

There were 23 patients who were referred to the Gynaecologic Oncology outpatient for evaluation of ascites, to rule out malignancy. The mean age of this patient group was 35 years (SD 14.5, range 14–65). The mean CA 125 was 333.5 [400.7 (9.09–1568)]. Ascitic fluid analysis confirmed TB in 26%; omental biopsy revealed TB in 69%, and operative diagnostic procedures (laparoscopy and laparotomy) were done in 15 of the 23 patients which had a positive pick up rate of 100% to confirm the diagnosis of TB. Culture of ascitic fluid/omental tissue and PCR yields were poor with a pick up rate of 33% and 6%.

Conclusions

Abdominal TB is common in India and can mimic ovarian malignancy, and hence, high degree of suspicion needed. The isolation of AFB is the gold standard for diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis but has a low yield in abdominal TB. Ultrasound-guided procedure is reasonable as an initial procedure. As much time can be lost in working up these patients through multiple diagnostic algorithms using ascitic tap, USG biopsy and then an operative procedure, diagnostic laparoscopy could be considered early in the work up. It is a simple, time-saving and cost-effective way of establishing a diagnosis sooner with least complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Worldwide, ovarian cancer is seventh in incidence and fifth in cancer-related mortality among women [1]. These cancers tend to present predominantly in advanced stages with a poor prognosis. Sometimes, their presentation is nonspecific with vague symptoms and multiple tests are done before a confirmatory diagnosis is reached. Abdominal tuberculosis with ascites may mimic disseminated ovarian cancer and has to be considered in the differential diagnosis [2].

India has the highest tuberculosis (TB) burden, accounting for 2.8 million cases of the 10 million cases seen globally [3]. Extra-pulmonary TB, though uncommon, may be seen in endemic regions, such as India. Abdominal TB, which is not so common as pulmonary TB, can be a source of significant morbidity and mortality and is usually diagnosed late due to its vague clinical presentation. Abdominal TB usually occurs in four forms: lymph nodal TB, peritoneal TB, gastrointestinal TB and visceral TB involving the solid organs [4]. Tuberculous peritonitis, the commonest cause of abdominal TB, accounts for 1–2% of all TB cases [5, 6].

Serum CA 125 can be elevated in both ovarian cancer and peritoneal tuberculosis [7]. Similar clinical and image findings lead to diagnostic difficulty and the challenge of distinguishing these two disease entities. A high index of suspicion with good clinical acumen can help reach the diagnosis earlier. More importantly, it is of much value to be able to rule out malignancy at the earliest and relieve the patient of anxiety.

The objective of this study was to describe the clinicopathological details in patients referred to the Gynaecologic Oncology Department with possible ovarian or primary peritoneal cancer where the final diagnosis turned out to be abdominal tuberculosis. We also wanted to analyse the various tests and their performance in detecting abdominal TB.

Methodology

We performed a retrospective review of patients evaluated for ascites and elevated serum CA 125 levels at a tertiary care teaching hospital in South India between January 2014 and December 2017. The Institutional Review Board approval was obtained. All patients who had been referred to the Department of Gynaecologic Oncology to rule out malignancy and where a diagnosis of TB was established were included as cases. Clinical information, demographic data and information on clinical investigations were collected from the electronic medical records.

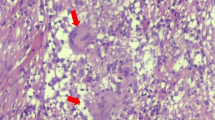

Straw-coloured ascitic fluid with high protein content of > 3 g%, predominant lymphocytosis with or without culture being positivity by MGIT or LJ medium and Expert TB PCR testing was considered as a positive test for ascitic tapping. USG-guided biopsy of omentum/adnexal mass with evidence of giant Langerhans cells, caseous necrosis and the presence of acid-fast bacilli on staining were considered as positive features to establish a diagnosis of TB. Findings on laparoscopy/laparotomy with pathognomic of TB like miliary tubercles with confirmatory histopathological findings mentioned above were conclusive for establishing a diagnosis of TB.

Frequency and percentages were calculated for categorical variable; mean ± SD was reported for continuous variables. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive values were calculated using SPSS 21.0 IBM, Bangalore.

Results

During the 3-year study period, 567 patients were operated upon with a provisional diagnosis of ovarian cancer, and 23 patients had a diagnosis of peritoneal tuberculosis by ultrasound-guided biopsy, diagnostic laparoscopy or laparotomy proceed frozen section.

The mean age of patients with TB was 35 (SD 14.5) years. A majority of these patients were those who came as referrals from elsewhere (91.3%). Two-thirds of these patients were married (69.6%) and parous (60.9%).

The most common presenting complaints were loss of weight (65%) and abdominal distention (65%). Some had fever and abdominal pain.

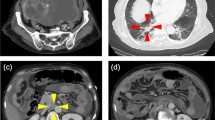

Most of these patients had a low BMI with a mean BMI of 19.1 (SD 3.7). At presentation, majority of them had an elevated serum CA 125 with an average of 335 (SD 407.5). On imaging, most patients had a pelvic mass, omental thickening and ascites (Tables 1, 2, Fig. 1).

Ascitic tap was done as a preliminary screening in six patients, ultrasound-guided omental biopsy in 13 and diagnostic laparoscopy in nine and laparotomy proceed with or without frozen section in seven of the 23 patients. Cultures obtained from ascitic fluid or omental tissue were positive in seven of the 23 patients. A few of the patients had a combination of procedures such as ascitic fluid tapping and ultrasound-guided (USG) biopsy (6/23), USG biopsy and laparoscopy/laparotomy (5/23) where we could not confirm the diagnosis of tuberculosis with the initial test (Table 3).

Ascitic fluid tapping alone yielded a positive detection rate of 26%, USG biopsy had a positive pick up rate of 69% and operative procedures of laparoscopy/laparotomy picked up a positive diagnosis almost 100% of the times based on clinical findings. Frozen section done on 4/15 patients was helpful in ruling out malignancy as well as establishing a positive diagnosis of TB. Where the frozen section came as no evidence of malignancy with chronic granulomatous condition, radical debulking surgery was abandoned in favour of an infective pathology such as TB (Table 4, Fig. 2).

There were a total of 15 operative diagnostic tests (laparoscopy and laparotomy). The commonest findings on laparoscopy were adhesions (12/15), ascites (10/15), military tubercles (10/15) on peritoneum and surface of intra-abdominal viscera, adnexal masses(5/15) and cocoon abdomen (4/15) in a few. Confirmation of TB by operative findings such as tubercles followed by biopsy was seen using laparoscopy in 100% and 83% by laparotomy and biopsy. The operative procedures were minor surgical procedures, and no complications were reported in our series of patients (Fig. 3).

Culture of the omental tissue/ascitic fluid with LJ medium, MGIT and Gene Expert by PCR done in 18 patients was found to be positive in 6/18 (33%) Expert PCR was detected only in 1/18 patients (6%) in our series.

Although USG biopsy seems like a reasonable first line diagnostic test with less side effects, acid-fast bacilli were seen in only two of the 21 biopsy slides which may be due to paucibacillary type of extra-pulmonary TB. Omentum was the tissue of choice for histopathology in about half the cases [10 (43.4%)], whereas it was a node or peritoneal tubercle/peritoneum in the other half [13 (56.5%)].

Follow-up data were available for 19 of the 23 patients. Antituberculosis therapy was taken for 6–12 months in 19 of these patients, whereas four patients defaulted therapy and did not come back for follow-up.

Discussion

Abdominal TB is the most common type of extra-pulmonary tuberculosis. Common sites of involvement in abdominal TB are: 1. gastrointestinal tract, 2. peritoneum, e.g. ascites, 3. lymph nodes, 4. solid organs, e.g. liver, spleen and pancreas. Abdominal TB usually presents with vague, nonspecific symptoms which make the diagnosis of the condition difficult and time consuming. With the development of better imaging techniques such as CT scan, it is possible to identify lesions which could be due to a chronic inflammation and differentiate it from a malignancy. The Lingenfelser criteria have been suggested to diagnose abdominal tuberculosis [8]. These include (a) clinical manifestations suggestive of TB, (b) imaging evidence indicative of abdominal TB, (c) histopathological or microbiological evidence of TB and/or (d) therapeutic response to treatment.

Tuberculous peritonitis, a type of abdominal TB, is a rare manifestation of tuberculosis, occurring in less than 1–2% of tuberculosis patients. It is still a very important cause of ascites in endemic areas. Cirrhosis, renal failure, diabetes mellitus, malignancy or other immune deficiencies such as AIDS are the high-risk groups for developing tuberculosis.

Signs and symptoms typically associated with peritoneal tubercles causing exudative ascites resemble those caused by advanced ovarian carcinoma and include abdominal distension, ascites and pelvic or adnexal masses. Fever and weight loss may be there in both groups. Many of these women go on to have radical surgery due to the difficulty of definitive preoperative diagnosis of ovarian cancer and the low negative predictive value of ascitic fluid cytology, cultures or other microbiological tests.

In our study, 39% patents had to undergo laparoscopy and 30% underwent laparotomy for establishing the diagnosis.

Tumour markers such as CA 125 lack specificity and may be elevated in many conditions, including tuberculosis. One such study showed that CA 125 titres higher than 1000 U/ml usually correlated with malignancy [9]. In the present study, the 25 patients with TBP had a mean CA 125 level of 333 IU/ml.

Imaging such as ultrasound, CT scan or MRI may aid in making a diagnosis of tuberculosis. Common findings in tuberculosis are omental stranding/thickening, peritoneal thickening, bulky adnexa or tube–ovarian complex masses, dense ascites, caseous nodes and soft-tissue mesenteric and omental infiltration. As compared to TB, omental caking, upper abdomen disease such as diaphragm involvement and loss of fat planes with hollow viscera may be significant findings in a malignancy.

Ultrasound-guided tru-cut biopsy has also been shown to be a valuable first-line approach [10]. It is safe, relatively inexpensive and consumes less time in obtaining tissue for microbiology as well as histopathology. The diagnosis of tuberculosis was achieved in 69% patients by USG-guided biopsy in our series. This is comparable to other studies.

Evaluation of ascitic fluid for protein content, cell counts and various microbiological tests such as MGIT and gene Expert PCR has been studied in the past [11]. PCR of ascitic fluid was positive for mycobacterium tuberculosis in only 6% of our cases which was lower than expected. Yield of test positivity seemed better when tissue-based samples were analysed as compared to fluid based. All forms of abdominal TB, especially ascitic type, tend to be paucibacillary. In these situations, the Expert MTB/RIF assay performs poorly [12]. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of the Expert MTB/RIF assay were 8.1%, 100%, 100% and 64.2%, respectively [16]. In our series too, the usefulness of these tests was limited and only 33% were found to be positive on testing by the various culture techniques. Maybe newer techniques like CBNAAT which is cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification test which detects the presence of TB bacilli and tests for resistance to rifampicin also could be employed to improve the diagnostic accuracy in such cases. [17].

If all the above points towards a possibility of tuberculosis but not confirmatory, then some treating clinicians may prefer empirical therapy with antituberculosis therapy. This is not found to be effective and may alter results of further testing. It could result in unnecessary liver damage and serious consequences [13].

Diagnostic laparoscopy or laparotomy may then be necessary however for definitive diagnosis, to differentiate it from disseminated cancer. Intraoperative frozen sections can aid in avoiding unnecessary extensive surgery. It is empirical to be able to differentiate cancer from tuberculosis on visualizing the disease via surgical methods. Since gynaecologic oncologists are familiar with carcinomatosis and its findings at surgery, the ability to differentiate between cancer and TB may be easier. To a certain extent, a negative diagnosis of cancer can be made by simply visualizing the findings. In a systematic review of 39 studies on tuberculous peritonitis, the diagnostic sensitivity of laparoscopic findings alone was 92.7% and confirmatory histopathology of the biopsy was 93% [5].

The findings at surgery included multiple diffuse involvement of the visceral and parietal peritoneum, white ‘miliary nodules’ or plaques, ascites, fibrinous strands and adhesions, adnexal masses, ‘cocoon’ abdomen and omental thickening. An adequate biopsy of the affected peritoneum or omentum with tubercles would be a good representative tissue which could be used for histopathology as well as microbiological tests [14].

Biopsy specimens in our series showed granulomas, epitheliod cells and Langerhans cells, but unfortunately, most of them were negative for acid-fast bacilli by staining.

Treatment for extra-pulmonary TB includes 6 months of treatment (with isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol) and was found to be adequate in patients with abdominal tuberculosis including peritoneal TB [15].

Conclusions

Abdominal TB can mimic ovarian malignancy, and hence, high degree of suspicion needed in an endemic region such as India. The isolation of AFB is the gold standard for diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis but has a low yield in abdominal TB. Ultrasound-guided procedure is reasonable in the initial period of diagnosis. Diagnostic laparoscopy should be considered early in the work up rather than laparotomy.

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

Gosein MA, Narinesingh D, Narayansingh GV, et al. Peritoneal tuberculosis mimicking advanced ovarian carcinoma: an important differential diagnosis to consider. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:88.

Global tuberculosis report 2018 of the WHO.

Debi U, Ravisankar V, Prasad KK, et al. Abdominal tuberculosis of the gastrointestinal tract: revisited. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(40):14831–40.

Sanai FM, Bzeizi KI. Systematic review: tuberculous peritonitis—presenting features, diagnostic strategies and treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22(8):685–700.

Koc S, Beydilli G, Tulunay G, et al. Peritoneal tuberculosis mimicking advanced ovarian cancer: a retrospective review of 22 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:565–9.

Bilgin T, Karabay A, Dolar E, et al. Peritoneal tuberculosis with pelvic abdominal mass, ascites and elevated CA 125 mimicking advanced ovarian carcinoma: a series of 10 cases. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2001;11(4):290–4.

Lingenfelser T, Zak J, Marks IN, et al. Abdominal tuberculosis: still a potentially lethal disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88(5):744–50.

Du LTH, Mohattane H, Piette JC, et al. Specificity of CA 125 tumour marker: a study of 328 cases of internal medicine. Presse Med (Paris, France: 1983). 1988;17(43):2287–91.

Oge T, Ozalp SS, Yalcin OT, et al. Peritoneal tuberculosis mimicking ovarian cancer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;162(2012):105–8.

Salgado Flores L, Hernández Solís A, Escobar Gutiérrez A, et al. Peritoneal tuberculosis: a persistent diagnostic dilemma, use complete diagnostic methods. Rev Med Hosp Gen Méx. 2015;78(2):55–61.

Rufai SB, Singh S, Singh A, et al. Performance of Xpert MTB/RIF on ascitic fluid samples for detection of abdominal tuberculosis. J Lab Phys. 2017;9:47–52.

Kumar R, Shalimar S, Bhatia V, et al. Antituberculosis therapy-induced acute liver failure: Magnitude, profile, prognosis, and predictors of outcome. Hepatology. 2010;51:1665–74.

Saxena P, Saxena S. The role of laparoscopy in diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis. Int Surg J. 2016;3:1557–63.

Jullien S, Jain S, Ryan H, et al. Six-month therapy for abdominal tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD012163.

Kumar S, Bopanna S, Kedia S, et al. Evaluation of Xpert MTB/RIF assay performance in the diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis. Intest Res. 2017;15(2):187–94.

Kasat S, Biradar M, Deshmukh A, et al. Effectiveness of CBNAAT in the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Res Med Sci. 2018;6(12):3925–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AT contributed to design, planning, conduct, data analysis and manuscript writing; AS, RG, DST and AP performed conduct, data analysis and manuscript writing; GR contributed to data analysis; PR and JS provided expert opinion and manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Statement

This was a retrospective study after obtaining ethics committee clearance.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Anitha Thomas is Associate Professor, Department of Gynaecologic Oncology, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu. Ajit Sebastian is Associate Professor, Department of Gynaecologic Oncology, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu. Rachel George is Professor, Department of Gynaecologic Oncology, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu. Dhanya Susan Thomas is Assistant Professor, Department of Gynaecologic Oncology, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu. Grace Rebekah is Associate Professor, Department of Biostatistics, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu. Priscila Rupali is Professor and Head of Department of Infectious Diseases, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu. Joy Sarojini Michael is Professor and Head of Department of Clinical Microbiology, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu. Abraham Peedicayil is Professor and Head, Department of Gynaecologic Oncology, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thomas, A., Sebastian, A., George, R. et al. Abdominal Tuberculosis Mimicking Ovarian Cancer: A Diagnostic Dilemma. J Obstet Gynecol India 70, 304–309 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-020-01322-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-020-01322-8