Abstract

Cancer-related sexual dysfunction is documented as one of the most distressing and long-lasting survivorship concerns of cancer patients. Canadian cancer patients routinely report sexuality concerns and difficulty getting help. In response to this gap in care, clinical practice guidelines were recently published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. A sweeping trend is the creation of specialized clinics for patients’ sexual health concerns. However, this much-needed attempt to address this service gap can be difficult to sustain without addressing the cancer care system from a broader perspective. Herein, we describe the implementation of a tiered systemic model of cancer-related sexual health programming in a tertiary cancer center. This program follows the Permission, Limited Information, Specific Suggestions, Intensive Therapy (PLISSIT) model, used previously for guiding individual practitioners. Visually, the model resembles a pyramid. The top 2 levels, corresponding to Intensive Therapy and Specific Suggestions, are comprised of group-based interventions for common cancer-related sexual concerns and a multi-disciplinary clinic for patients with complex concerns. The bottom 2 levels, corresponding to Permission and Limited Information, consist of patient education and provider education and consultation services. We describe lessons learned during the development and implementation of this program, including the necessity for group-based services to prevent inundation of referrals to the specialized clinic, and the observation that creating specialized resources also increased the likelihood that providers would inquire about patients’ sexual concerns. Such lessons suggest that successful sexual health programming requires services from a systemic approach to increase sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A pervasive and long-standing effect of cancer treatment, cancer-related sexual dysfunction reduces quality of life and negatively impacts intimate relationships [1, 2]. Sexual dysfunction does not typically resolve with time and can persist, or even worsen, for years after cancer treatment [3,4,5]. Sexual difficulties are highly prevalent across the spectrum of cancer diagnoses (e.g., breast 16–63%; prostate 6–96%; gyne-oncological 13–91%; hematologic 16–78%; colorectal 12–79%; head/neck 30–53%) [6]. Indeed, virtually all cancer treatments (e.g., chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgical treatments, endocrine therapy, and hemopoietic stem cell transplants) have the potential to negatively impact patients’ sexual health [6]. Common concerns include reduced sexual desire, erectile dysfunction, vaginal dryness, and painful intercourse. Cancer-related sexual dysfunction is multi-faceted and extends beyond changes in sexual function, causing sexual distress, disruptions to body- and self-image, and strains on intimate relationships [7,8,9,10].

The Canadian Partnership Against Cancer reports national averages of patients experiencing changes in sexuality (42%), body image (39%), and relationships with family and partners (33%) [11]. These concerns ranked in the top 5 emotional concerns and immediately followed anxiety and depression. Between 21 and 33% of patients sought help for these concerns [11]. Unfortunately, patients report difficulty in accessing help (27%) and typically wait longer than 6 months before receiving it [11].

Patient reported outcomes reveal poor satisfaction with services for cancer-related sexual concerns. Although over 74% of patients indicate that discussions about sexuality with health care providers (HCPs) are important [12], as many as 50% of patients report dissatisfaction with the sexual health information received from HCPs [12]. Sexual discussions with HCPs tend to occur more often in particular tumor groups; approximately 80% in prostate, 40% in colorectal, and less than 30% in breast and lung [12]. Rates of oncology providers who engage in discussion are low [5]. The proportion of physicians who self-report discussing sexuality (6%), inquiring about sexual problems (2%), and providing information about treatment effects on sexuality (16%) are low, despite high endorsement (98%) that it is the provider’s responsibility to do so [13].

Specifically in Alberta, Canada, surveys across all cancer patients demonstrate substantial rates of dissatisfaction, as high as 65% regarding information provided on relationship changes, and 50% regarding information provided on changes in sexual activity [14]. More specifically, a survey conducted among radiation therapy patients revealed that 76% wanted written information and 69% wanted verbal information about sexual health and intimacy, and 43% would have welcome a sexual health consult if it were available [15].

There has been a call within cancer care organizations to improve patient reported outcomes by addressing the gap in sexual health care. A sweeping trend is the creation of specialized cancer-related sexual health clinics [16,17,18]. Advantages of specialized clinics include protected time to prioritize sexual health concerns within cancer care, access to specialized knowledge, and provision of comprehensive and integrated biopsychosocial care. Such specialized services are in line with recently published clinical guidelines [19].

The Sexual Health Clinic

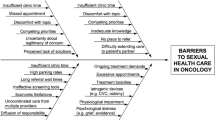

A specialized sexuality clinic allows for dedicated time for sexual health concerns typically not prioritized in busy follow-up clinics focusing on cancer status. Barriers to addressing sexuality in routine follow-up visits abound and commonly include patient or HCP reticence to broach the topic, lack of specialized knowledge or experience, and lack of time [20].

Expertise in both sexuality and oncology is required to adequately address the sexual impact of cancer treatment [21]. Commonly occurring issues arising from treatment are complex; examples include radiation-induced vaginal stenosis, vaginal architectural changes secondary to vaginal graft vs. host disease, profound erectile dysfunction in the context of androgen deprivation therapy, and localized estrogen replacement in the context of hormone-sensitive cancer. Competence to treat these conditions requires sufficient expertise in the complexities of cancer treatment and its sequelae. Oncologists often report a lack of expertise and knowledge in sexual health thereby limiting opportunities for assessment and treatment [22]. Except when the direct tumor site is associated with the sexual and reproductive organs, oncology assessments do not routinely extend to the genitals. Even in the field of gynecologic oncology, fewer than 50% of physicians include a sexual history in their patient assessments [23]. In our experience, patient referrals indicate that specialist clinicians (e.g., gynecologists, urologists) report being under-equipped to deal with the complex sequelae of cancer treatments. Sexual education among generalist clinicians is also lacking [24].

Finally, because sexual health is influenced by a variety of factors including the psychological and relationship context, exclusive biomedical care is often associated with challenges in instituting and following through with treatments. Psychological support is fundamental in improving outcomes related to poor treatment adherence (e.g., vaginal dilation, erectile aids in prostate cancer, emotional avoidance of sexual activity or sexual treatments) [25,26,27]. Clinical guidelines for managing cancer-related sexual dysfunction indeed emphasize the role of psychosexual counselling [19]. The best cancer care services are those that incorporate multi-disciplinary teams [28], and the same follows with sexuality services, where assessment and treatment are offered from a biopsychosocial perspective [29].

We conducted an environmental scan of the sexual health services offered in cancer care across Canada (Robinson, J. and Barbera, L., May 2018, personal communication; Walker, L. and Matthew, A., July 2018, personal communication; Walker, L., Voorn, M., and Turner, A., July 2018, personal communication, Walker, L., and Ryan, M. October 2019, personal communication) [30]. Common challenges include meeting high demand for service, managing extended wait times, and finding sustainable funding [17, 18, 31, 32]. Programs attempted to address these challenges in unique ways. Some clinics restricted services (e.g., women only, prostate cancer only). Some, rather than providing biopsychosocial care, provided only medical or psychosocial treatment. The vast majority of clinics were situated in centers where the clinic was the only sexual health service provided. Learning of these challenges, we designed a systemic approach to guide sexual program development that expands beyond the specialized multi-disciplinary cancer clinic. The following paper presents a model of sexual health care developed within a publicly funded multi-center cancer care system.

The Program Model

The program was designed based on the P-LI-SS-IT model, a guide for sexual assessment and intervention largely used to guide individual practitioners’ interactions with patients [33]. To the best of our knowledge, this is its first application to a care system. The P-LI-SS-IT model posits that providers first work to establish an environment of Permission with patients. This is done by inquiring about sexuality, thereby affirming that the topic is a legitimate one for discussion within healthcare consultations. Next, providers offer Limited Information to patients about potential sexual health changes and possible solutions. Specific Suggestions follow, with more in-depth discussion of the sexual implications of cancer treatment and specific interventions for sexual dysfunction. At this level, the provider should have a good understanding of the complexities of sexual changes and the challenges that arise in implementing treatments. Several treatment options may need to be tried, yet the clinician should also be able to identify when a referral is warranted for more advanced assessment and intervention. Intensive Therapy is directed to patients with more complex problems, requiring specialized physiological and/or psychological sexual intervention. It has been estimated that most patients can be treated within the first three tiers of service and that only 20% of cancer patients require Intensive Therapy [34].

From Theory to Practice

Within the context of Alberta, cancer care is provided in two major tertiary cancer sites, with several smaller regional centers and clinics. Beginning in these tertiary sites, we established a sexual health leadership team made up of HCPs from a variety of backgrounds, with specialized training in sexuality and cancer. We formed the Oncology and Sexuality, Intimacy and Survivorship (OASIS) program. We sought to offer comprehensive, integrated, truly multidisciplinary services for cancer patients suffering from sexual distress and dysfunction. The team includes advanced practice and registered nurses, psychosocial oncologists, radiation oncologists, radiation therapists, a gynecologic oncologist, and an occupational therapist (OT).

There is a multitude of barriers to the application of P-LI-SS-IT within cancer care (e.g., lack of time in clinic, competing clinical demands, lack of knowledge or expertise, discomfort or fear of embarrassment, lack of referral resources, poor access to or awareness of patient educational materials). In order to address these barriers, we developed a tiered model of sexual health service provision. The model is presented as a pyramid of care (Fig. 1) with services provided at the bottom being broad reaching, potentially benefiting all patients. Services provided toward the top are applicable to patients with complex problems that need specialized intervention.

The OASIS pyramid model of sexual health care in oncology provides services in a tiered fashion with broader reaching services at the bottom and more specialized limited services at the top. This is consistent with the P-LI-SS-IT model. Services such as print and online patient education resources, and staff education and consultation are broad reaching, potentially benefiting all patients. These services largely align with the P-LI-SS-IT levels of Permission and Limited Information (though some clinicians may occasionally offer simple suggestions). Services provided in the top 2 levels of the pyramid, such as targeted group interventions and a multidisciplinary specialty clinic, are necessary for only the subgroup of patients with complex sexual health problems who require treatment from specialists with expertise in oncology and sexuality. These services align with the P-LI-SS-IT levels of Specific Suggestions and Intensive Therapy. In this way, the lower levels of the pyramid support the larger system as a whole. Generalists are supported to meet the needs of the majority of patients who present with more with straight-forward concerns, in a cost-effective manner, whereas more expensive specialist services are reserved for a smaller subset of patients with complex concerns.

The pyramid is a unique adaptation of the P-LI-SS-IT model to a program of sexual health care. Thus, we aimed to improve patient access to information and better equip staff to provide Permission and Limited Information (i.e., levels 1 and 2) and also develop more accessible services for patients at the levels of Specific Suggestions (i.e., level 3) and Intensive Therapy (i.e., level 4). A unique and fundamental feature of this program model is that services are tiered so that patients’ needs are matched to the required intensity of service in an economical and efficient format. Patients with more straight-forward needs receive services on the lower levels and patients with more complex needs receive the more intensive, higher-level services.

Alignment of each patient’s unique needs with the appropriate level of service is an essential component of this program model. This triaging process is facilitated by a registered nurse with specialized training in sexual health. Administrative staff initially receive patient referrals via a dedicated phone and fax line. Referrals are then forwarded to the triage nurse for assessment. The administrative assistant also provides access to print and online patient educational materials when patient queries can be solved with education materials alone. The specialty practice nurse evaluates all patient referrals and determines which services within the program are most appropriate for each patient. The triage assessment includes the following components: a screening assessment to determine the nature of the patients’ sexual health concerns; the interventions they have already tried (e.g., vaginal moisturizers, PDE5 inhibitors); and the particular psychosocial context, values, and goals that inform their need for support. Importantly, the specialty practice nurse registers patients in the specific service(s) that best serve their needs and also coordinates any required follow-up services.

Levels 1 and 2: Patient Education and Staff Education/Consultation

In order to establish an environment of Permission, we aimed to improve clinicians’ capacity for inquiring about sexuality with their patients. First, we aimed to disseminate the message that sexual health needs are high and remain inadequately addressed. Through a series of cancer center rounds presentations, we disseminated that message that local patients were dissatisfied with sexual health care. By building awareness of the gap in clinical care, providers appear to be more receptive to the educational opportunities (e.g., attending in-services, continuing medical education offerings) needed to fill that gap. Next, interested clinicians were offered follow-up training (i.e., a one-hour in-service entitled “Opening Conversations about Sexuality”), in order to develop skills and confidence to initiate conversations about sexuality with their patients [35].

Our efforts to improve provision of Limited Information were twofold: (1) direct to patients and (2) via healthcare provider. We created a series of printed and web-based education materials that were then standardized across our province. These materials explained the sexual sequelae of cancer treatments and strategies to manage those effects. We generated a series of 4 booklets: Sexual Information for Men with Cancer, Sexual Information for Women with Cancer, Fertility & You, and Loss of Sexual Desire. These materials were adapted online and are hosted on MyHealthAB.ca (Fig. 2) [36]. The site was visited 3248 times in the first year of launch, 3944 times in the second year, with an average of 1015 visits per quarter. Visits for the most recent quarter of 2019 show a steady increase (1944 views from April to June 2019). The most frequently viewed topic pages include Sexual Positions (4996 views), Introduction to Cancer and Sexuality: What about Sex after a Cancer Diagnosis? (1123 views), About OASIS (612 views), Overview of Female Anatomy (556 views), and Vaginal Dilators (410 views) [36]. Residents of Canada, the USA, the Philippines, and South Africa had the highest number of site visits, with 43%, 14%, 5%, and 4% of total visits, respectively [36]. Visitors from several countries on the continents of Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia comprised the remaining website views, with no countries accounting for more than 2.63% of total views [36]. In terms of website visitors from within Canada, 57% of visits were from the province of Alberta; the remaining visits were from British Columbia (18%), Ontario (12%), Saskatchewan (5%), Manitoba (3%), Quebec (3%), and Newfoundland and Labrador (2%) [36].

Online Patient Education Materials. Content of online sexual health resources, hosted on the MyHealth.Alberta.ca website. Integral to the provision of Limited Information is the availability of online-accessible sexual health educational materials. These web-based materials offer patients and healthcare providers information about the sexual impact of cancer treatments, and about the strategies that exist to manage sexual side effects. Information is organized within the host website, MyHealthAB.ca, under the homepage Cancer and Sexuality, and are organized within according to key cancer-related impacts on sexual health (e.g., vaginal discomfort and dryness, fertility, body image, erectile dysfunction). Resources pertaining to the impacts of cancer on sexual relationships are also included. All topics are listed in the Figure 2 under their relevant headings. These online patient educational materials are available at: https://myhealth.alberta.ca/HealthTopics/cancer-and-sexuality

Dissemination efforts to promote uptake of the patient education materials included staff education (e.g., via grand rounds, in-services and email blasts). Providers were encouraged to provide these materials in response to patients’ sexual health inquiries. Materials were also made directly available to patients by posting on patient education displays outside of clinics. This strategy was thought to promote an environment of Permission while simultaneously making information directly available to patients without providers needing to be the gatekeepers to that information.

Through a quality improvement initiative, we offered training in cancer and sexual intervention to frontline clinicians [37]. A team of pan-Canadian psychosocial oncology experts, led by McLeod and Robinson, created a series of online university accredited courses on sexuality and cancer. These Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology Association Inter-Professional Psychosocial Oncology Distance Education Project courses are currently hosted by the deSouza Institute [38]. A total of 24 clinicians (nurses, radiation therapists, social workers, psychologists, and occupational therapists) across Alberta were trained in these courses. Many of the clinicians who had completed the training became sexual health champions, working to disseminate sexual health information in their respective centers.

A foundation of the P-LI-SS-IT model is that referral resources are available for providers to refer their patients to when they reach the limit of their competence. Indeed, a recent evaluation within the Tom Baker Cancer Centre demonstrated that the development of specialized sexual health services actually improved Permission by increasing HCPs’ likelihood of initiating conversations about sexuality with patients [39]. Without resources at the Specific Suggestions and Intensive Treatment levels, Permission and Limited Information are also likely to be impeded.

Level 3: Group-Based Interventions for Specific Populations

Example in Women’s Health

A two-hour group-based workshop, called the LowDown on Down There, was implemented, to addresses vaginal changes post-cancer treatment. Importantly, this workshop addresses more than just sexual concerns and focuses more generally on vaginal health, as many patients are not sexually active and can even experience debilitating vaginal health concerns unrelated to sexual activity [40]. This approach is consistent with the design of the Sexual and Women’s Health Clinic at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center [16]. This intervention is not just educational; it also aims to support and sustain patient use of interventions for vaginal and sexual concerns. Participants are provided with specific instruction about evidence-based strategies (e.g., vaginal dilation, vaginal moisturizers, lubricants, pelvic floor physiotherapy, adapting sexual practices) to treat common physical symptoms (e.g., vaginal dryness, painful intercourse, reduced sexual sensation) and reduced sexual desire (e.g., psychoeducation about sexual response, introduction to sensate focus, and mindfulness meditation). Samples (e.g., lubricants, moisturizers) are distributed and a variety of kinds of sexual aids (e.g., dilators, sexual toys) are presented in order to reduce barriers to access and use.

Preliminary results for the first 67 participants in this workshop, demonstrated that 3 months following workshop attendance, women experienced significant reductions in: sexual distress, bother associated with their primary presenting concern, and self-reported vaginal symptom severity [41]. From June 2016 to December 2018, a total of 206 women have participated in the program. A manuscript including a full-scale evaluation is forthcoming but baseline outcomes are presented in Millman et al., (in press).

Example in Men’s Health

With collaboration from the Prostate Cancer Centre (Calgary, AB), we developed an inter-disciplinary Intimacy after Prostate Cancer workshop [42]. This couples’ workshop is facilitated by two clinical psychologists and a sexual medicine expert urologist. Couples are provided with information about sexual changes and biomedical or mechanical treatment options (e.g., oral medications, vacuum erection devices, intra-cavernosal injections, vibrators), as well as psychological treatment options (e.g., sensate focus, alteration of sexual practices, communication strategies). Couples are encouraged to consider the role of their values when choosing a treatment option and developing a treatment plan. Results of this workshop indicate patients and partners report improvements in the medical impact of cancer treatment on sexual function [43] and in relationship satisfaction [42]. Partners demonstrated additional improvement in sexual interest, problems, and overall sexual function [43]. Over 258 couples have been served through this program.

Intensive Therapy

Level 4: The Multi-Disciplinary Sexual Health Clinic

We, like other centers, also developed a specialized multi-disciplinary clinic to provide concurrent physiological and psychological sexual assessment and intervention, as well as functional assessment and intervention (OT). Patients referred to the program are first triaged using screening measures and a brief interview. Patients are then seen by a psychologist and either a nurse practitioner or physician. All members of the multi-disciplinary team have specialized training in sexual health and oncology. At subsequent clinic visits, most patients continue to receive follow-up services from both providers but some see only one provider.

This multi-disciplinary sexual health clinic was instated in the two tertiary cancer centers during two different time periods. The first of our two pilot clinics was instituted at the Cross Cancer Institute, between 2014 and 2016 [44]. A total of 64 patients were seen in the twice monthly clinic during the pilot period. A description of the clinic implementation model is in press [45]. Focusing on the clinic implementation at the top of the pyramid, demand for clinic service was high. We learned from this pilot, that without embedding the clinic within a program that included sufficient resources at the lower levels of the pyramid model, the clinic was difficult to sustain due to high demand and intolerably lengthy wait lists. As the clinic grew, a need for group resources was recognized, which helped to alleviate demand and reduce patient wait time. Furthermore, without adequate support to frontline providers to promote education and commence first-line treatments with patients, all sexual health referrals were directed to the specialized clinic. Consistent with the P-LI-SS-IT model, specialty clinic consultations should be reserved for only patients who require Intensive Treatment, while patients with more straightforward concerns or questions can have their concerns addressed in regular clinic visits or group programs.

The second pilot of the multi-disciplinary sexual health clinic occurred at the Tom Baker Cancer Centre (TBCC) between 2016 and 2018. Insights were applied from the experience of the first clinic pilot and the clinic was launched only after successful implementation of resources at the lower levels of the pyramid/P-LI-SS-IT model. This approach allowed for patient referrals to be effectively triaged to these levels of service (e.g., workshops, educational materials) with only a subset of patients requiring Intensive Treatment in the multi-disciplinary clinic. A total of 79 patients were seen during the 2-year pilot of this TBCC clinic, with 36 patients returning for between 1 and 6 follow-up visits. A full report on the patient characteristics and clinic processes is forthcoming.

Many lessons were learned during the process of the first pilot of the clinic. Some of these learnings were implemented partway through the first pilot, but were fully operational by the launch of the second clinic pilot. This allowed for advantages including the provision of dedicated clinic administrative and nursing support, the development of group-based educational programs (which reduced time spent in clinic educating patients, and the development of sufficient expertise allowing for more expedited service delivery. Other advantages included offering clinical services within the context of grant-funded applied clinical research programs, and extending the clinic as a learning environment for clinical trainees from a variety of disciplines.

Care pathway: Resource Utilization Through the Pyramid Model

Figure 3 represents a care pathway in which patients and providers can access the services depicted in the pyramid model. First, there are two access points to services: provider and patient. Providers (e.g., some of whom may have received education by attending the “opening conversations about sexuality” inservice) may identify and assess for patients’ sexual concerns. The provider can then direct the patient to "Print and Online Patient Information Resources", or the provider can access "Staff Education and Consultation" with an OASIS team member. Both of these resources will improve the care the provider directly gives to patients. Alternatively, the provider can refer patients directly to OASIS programs where they are seen by an OASIS provider. Patients can also access resources directly (e.g., print and online patient information resources, or self-refer to OASIS). Once referred to OASIS, a triage assessment is conducted and patients are registered for "Group Interventions" or the "Multi-disciplinary Clinic". Once these services are completed, patients are discharged back to the referring provider.

Care pathway: resource utilization through the pyramid model. The care pathway depicts various routes by which patients can be referred to the many types of services defined within the pyramid model (Fig. 1). Two primary access points to sexual health services are represented at the top of the care pathway: provider-led and patient-led access. Providers who identify and assess patients’ sexual health concerns may access services through 3 pathways, as visualized in the left branch of the care pathway: (1) providers direct patients to Print and Online Patient Resources; (2) providers consult with members of the OASIS team to inform their own direct service provision to patients, (3) providers directly refer patients to the OASIS program. Patient-led access is represented in the right branch of the care pathway, and involves access through 2 different paths: (1) self-direction to Print and Online Patient Information Resources; (2) self-referral to the OASIS program via phone call to a member of the OASIS administrative staff. As pictured in the bottom section of the care pathway, all referrals to the OASIS program, via health care provider or patient, are reviewed by a triage nurse. Referred patients complete a telephone assessment with the triage nurse, after which they are registered for either Group Interventions or the Multidisciplinary Clinic. When utilization of these services is complete, patients are discharged back to their referring health care provider.

Conclusions

A sustainable program is one that offers both breadth and depth of sexual health service. Such a program must suitably equip frontline providers with confidence to work with all cancer patients by providing permission, supporting inquiry about needs, and facilitating access to informational resources. Staff also need to be supported with consultation and referral resources when they reach the limits of their capacity. In the same way, this programmatic approach facilitates access to specialized service for patients with complex problems. Neither end of the spectrum—top or bottom of the pyramid—can be successfully sustained, without the other. A comprehensive program model that addresses all aspects of care must consider building a foundation sufficient to support specialized services in order to avoid inundating that service beyond capacity with patients who do not require that level of service intensity. Established sexual health clinics may find that efficiency can be improved with group-based interventions and continued support for equipping frontline clinicians to address more straightforward sexual health concerns. Centers looking to develop resources within the organization may benefit from following a similar pyramid model, which will ultimately improve patient care.

Research Support

This manuscript was funded in part by the Calgary Foundation and the Alberta Cancer Foundation.

References

Bober SL, Sanchez Varela V (2012) Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: challenges and intervention. J Clin Oncol 30:3712–3719

Hawkins Y, Ussher J, Gilbert E, Perz J, Sandoval M, Sundquist K (2009) Changes in sexuality and intimacy after the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. Cancer Nurs 32:271–280

Hoffman RM, Gilliland FD, Penson DF, Stone SN, Hunt WC, Potosky AL (2004) Cross-sectional and longitudinal comparisons of health-related quality of life between patients with prostate carcinoma and matched controls. Cancer 101:2011–2019

Schover LR, van der Kaaij M, van Dorst E, Cruetzberg C, Huyghe E, Kiserud CE (2014) Sexual dysfunction and infertility as late effects of cancer treatment. EJC Suppl 12(1):41–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcsup.2014.03.004

Lindau ST, Gavrilova N, Anderson D (2007) Sexual morbidity in very long term survivors of vaginal and cervical cancer: a comparison to national norms. Gynecologic Oncology. doi. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.05.017

Varela VS, Zhou ES, Bober SL (2013) Management of sexual problems in cancer patients and survivors. Curr Probl Cancer 37:319–352

Ratner,E.S., Kelly, A.F., Schwartz, P.E., & Minkin, M.J. 2010. Sexuality and intimacy after gynecological cancer. Maturitas 66: 23-26.

Stead ML, Fallowfield L, Selby P, Brown JM (2007) Psychosexual function and impact of gynaecological cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 21:309–320

Wittmann D (2016) Emotional and sexual health in cancer: partner and relationship issues. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 10:75–80

Sadovsky R, Basson R, Krychman M, Morales AM, Schover L, Wang R, Incrocci L (2010) Cancer and sexual problems. Journal of Sexual Medicine 7:349–373

Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. 2018. Experiences of cancer patients in transition study: emotional challenges.

Flynn KE, Reese JB, Jeffery DD, Abernethy AP, Lin L, Shelby RA, Porter LS, Dombeck CB, Weinfurt KP (2012) Patient experiences with communication about sex during and after treatment for cancer. Psycho-oncology 21:594–601

Hautamaki K, Miettinen M, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Aalto P, Lehto J (2007) Opening communication with cancer patients about sexuality-related issues. Cancer Nurs 30:399–404

Picker NCR. 2013. Alberta Health Services Corporate Report: February-August 2013.

Belbeck, A. and A. Turner. 2013. Sexual health and intimacy issues for female cancer patients receiving radiation therapy. What is the radiation therapist’s role?.

Carter J, Stabile C, Seidel B, Baser RE, Gunn AR, Chi S, Steed RF, Goldfarb S, Goldfrank DJ (2015) Baseline characteristics and concerns of female cancer patients/survivors seeking treatment at a Female Sexual Medicine Program. Support Care Cancer 23:2255–2265

Barbera L, Fitch M, Adams L, Doyle C, Dasgupta T, Blake J (2011) Improving care for women after gynecological cancer: the development of a sexuality clinic. Menopause 18:1327–1333

Matthew A, Lutzky-Cohen N, Jamnicky L, Currie K, Gentile A, Santa Mina D, Fleshner N, Finelli A, Hamilton R, Kulkarni G, Jewett M, Zlotta A, Trachtenberg J, Yang Z, Elterman D (2018) In Press. The Prostate cancer Rehabilitation Clinic: a bio-psychosocial clinic for sexual dysfunction after radical prostatectomy. Curr Oncol

Carter J, Lacchetti C, Andersen BL, Barton DL, Bolte S, Damast S, Diefenbach MA, DuHamel K, Florendo J, Ganz PA, Goldfarb S, Hallmeyer S, Kushner DM, Rowland JH (2018) Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation of Cancer Care Ontario Guideline. JCO 36:492–511

Fitch MI, Beaudoin G, Johnson B (2013) Challenges having conversations about sexuality in ambulatory settings: part II--health care provider perspectives. Clin J Oncol Nurs 23:182–196

Lindau ST, Abramsohn EM, Baron SR, Florendo J, Haefner HK, Jhingran A, Kennedy V, Krane MK, Kushner DM, McComb J, Merritt DF, Park JE, Siston A, Straub M, Streicher L (2016) Physical examination of the female cancer patient with sexual concerns: what oncologists and patients should expect from consultation with a specialist. CA Cancer J Clin 66:241–263

Bober SL, Reese JB, Barbera L, Bradford A, Carpenter KM, Goldfarb S, Carter J (2016) How to ask and what to do: a guide for clinical inquiry and intervention regarding female sexual health after cancer. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 10:44–54

Wiggins DL, Wood R, Granai CO, Dizon DS (2007) Sex, intimacy, and the gynecologic oncologists: survey results of the New England Association of Gynecologic Oncologists (NEAGO). J Psychosoc Oncol 25:61–70

Humphery S, Nazareth I (2001) GPs’ views on their management of sexual dysfunction. Fam Pract 18:516–518

Law E, Kelvin JF, Thom B, Riedel E, Tom A, Carter J, Alektiar KM, Goodman KA (2015) Prospective study of vaginal dilator use adherence and efficacy following radiotherapy. Radiotherapy and Oncology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2015.06.018

Matthew AG, Goldman A, Trachtenberg J, Robinson J, Horsburgh S, Currie K, Ritvo P (2005) Sexual dysfunction after radical prostatectomy: prevalence, treatments, restricted use of treatments and distress. J Urol 174:2105–2110

McCallum M, Lefebvre M, Jolicoeur L, Maheu C, Lebel S (2012) Sexual health and gynecological cancer: conceptualizing patient needs and overcoming barriers to seeking and accessing services. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 33:135–142

Soukup T, Lamb BW, Arora S, Darzi A, Sevdalis N, Green JS (2018) Successful strategies in implementing a multidisciplinary team working in the care of patients with cancer: an overview and synthesis of the available literature. J Multidiscip Healthc 11:49–61

Rullo J, Faubion SS, Hartzell R, Goldstein S, Cohen D, Frohmader K, Winter AG, Mara K, Schroeder D, Goldstein I (2018) Biopsychosocial management of female sexual dysfunction: a pilot study of patient perceptions from 2 multi-disciplinary clinics. Sexual Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esxm.2018.04.003

Walker, L. M., A. Hills and J. W. Robinson. 2014. What sexual health services are provided to cancer patients and their partners in Canada? (Poster Presentation & Abstract).

Tracy M, McDivitt K, Ryan M, Tomlinson J, Brotto LA (2016) Feasibility of a sexual health clinic within cancer care: a pilot study using qualitative methods. Cancer Nurs 39:E32–E43

Elliott S, Matthew A (2018) Sexual recovery following prostate cancer: recommendations from 2 established Canadian sexual rehabilitation clinics. SMR 6:279–294

Annon, J. S. 1976. Behavioral treatment of sexual problems: brief therapy. (1976).Behavioral treatment of sexual problems: Brief therapy.xv, 166 pp.Oxford, England: Harper & Row.

Schover LR (1997) Sexuality and fertility after cancer. Wiley, New York

Walker, L. M. 2015. Characterizing the sexual health needs of oncology patients: developing a sexual health service (Oral Presentation).

OASIS Program, Alberta Health Services. 2016. Cancer and sexuality: what is OASIS?. https://myhealth.alberta.ca/HealthTopics/cancer-and-sexuality/Pages/about-oasis.aspx.

Walker, L. M., A. Driga, J. Turner, T. Hutchison, J. W. Robinson, A. Ayume and E. Wiebe. October 17, 2018. Educating sexual health champions in oncology (poster presentation).

de Souza Institute. 2018. Quality continuing education for health care professionals. https://www.desouzainstitute.com/.

Walker, L. M. 2018. Oncology and sexuality, intimacy and survivorship program: proposal & pilot evaluation results.

Huang AJ, Moore EE, Boyko EJ, Scholes D, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Fihn SD (2010) Vaginal symptoms in postmenopausal women: self-reported severity, natural history, and risk factors. Menopause 17:121–126

Millman, R. D., C. S. Sears, N. Jacox, R. Booker, P. Santos-Iglesias, J. W. Robinson and L. M. Walker. 2018. The LowDown on down there: evaluating a single-session vaginal health workshop for women diagnosed with cancer (poster presentation & abstract). Society for Sex Therapy & Research, 43rd Annual Conference.

Walker LM, King N, Kwasny Z, Robinson JW (2017) Intimacy after prostate cancer: a brief couples’ workshop is associated with improvements in sexual function and relationship distress. Psycho-Oncology 26:1336–1346

Hampton AJ, Walker LM, Beck AM, Robinson JW (2013) A brief couples’ workshop for improving sexual experiences after treatment for prostate cancer: a feasibility study. Support Care Cancer 21:3403–3409

Duimering A, Turner J, Andrews E, Driga A, Ayume A, Robinson JW, Walker LM, Wiebe E (2018) A multidisciplinary clinic experience sexual health care for oncology patients. Radiother Oncol 129:S127

Duimering, A., L. M. Walker, J. Turner, E. Andrews-Lepine, A. Driga, A. Ayume, J. W. Robinson and E. Wiebe. Quality improvement in sexual health care for oncology patients: a canadian multidisciplinary clinic experience. Support Care Cancer In Press.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Carly Sears for her careful review and assistance with manuscript submission and revisions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Walker, L.M., Wiebe, E., Turner, J. et al. The Oncology and Sexuality, Intimacy, and Survivorship Program Model: An Integrated, Multi-disciplinary Model of Sexual Health Care within Oncology. J Canc Educ 36, 377–385 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-019-01641-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-019-01641-z