Abstract

This research was made in the faculty of Social Communication and Journalism of a Colombian private university, renowned for its high-quality standards, with the goal to identify the actual characteristics of its organizational culture and its relationship in favor of innovation. This study was made with a mixed approach and involved compiled information gathered by using two instruments: the Inventory of Organizational Culture in Education Institutions (ICOE), designed by Marcone and Martin in Psycothema, 15(2), 292–299 (2003), and the TB Test, designed by Bridges in The character of organizations: Using personality type in organization development. Davies-Black Publishers (2000), as well as semi-structured interviews done to professors and administrative staff. The gathered information was compared with both theoretical models of cultural analysis built for superior education organizations and representative researchers in the area of organizational culture for innovation, a field of study broad and consolidated nowadays but one that is not usually geared toward understanding and explaining the relationship between organizational culture and innovation in high education organizations. Our findings let us make a characterization of the organizational culture of the faculty and identify its cultural strengths and weaknesses regarding adopting and favoring innovation. Also, this empirical research adds up to an effort to make studies regarding organizational culture for innovation specifically geared toward high-education organizations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although business innovation is currently seen as one of the essential capacities of organizations that seek to increase their competitiveness while being sustainable, its implementation varies and depends considerably on the features of organizational culture and the ability of the leaders to embrace the challenges and transformations brought about by innovation. However, the lack of a consensus on what both innovation and culture are and the different ways and perspectives in which these components have been studied, makes it difficult to identify how organizational culture affects each enterprise in its effort to implement innovation.

As part of these efforts, it is acknowledged that high-education organizations have been making adjustments and changes in order to implement innovation, but there is a lack of studies that show strategies designed and oriented to meet that goal, as well as the way in which the characteristics of the organizational culture of those organizations can either favor or not the intention to implement innovation. This is worrying, because high-education organizations, together with enterprises and organizations among many economic and governmental sectors, have to focus their actions on a team effort to promote socioeconomic development and innovative processes, especially in need in Latin America (Jasso et al., 2017).

The circumstances previously stated served as a starting point for the development of this research, which was made in the faculty of Social Communication and Journalism from a renowned high education institution located in Colombia. The information was gathered through questionnaires and interviews and was compared with findings coming from the few studies made in the country that are in line with our problem of study (Issa-Fontalvo, 2017; Prieto et al., 2020), from the model of culture analysis of Kezar and Eckel (2002), and from what is proposed by renowned authors in the field of innovation-oriented culture studies: Martins and Martins (2002); Martins and Terblanche (2003); Jamrog et al. (2006); Sharifirad and Ataei (2012); Jenkins, (2014) and Daher (2016); among others.

A Literature Review

We are immersed in a knowledge society. Fernández et al. (1998) argue that an organization’s knowledge and information—called intangible assets—are the decisive factors for increasing its market competitiveness; they state that organizational culture plays an essential role in the intangible asset known as organizational capital. Though many organizations acknowledge the importance of innovation in an increasingly dynamic and competitive market, its implementation does not always respond satisfyingly to organizational needs and expectations. This is due in part to not understanding the definition, complexity, and reach of the innovation concept (Morales & León, 2013) or because of the absence of an organizational culture aimed at adopting innovation.

From the standpoint of knowledge management in universities, Schmitz et al. (2016) made two assertions: universities must work together with the industrial and government sectors to promote socioeconomic development and innovation and, to that aim, they must question and overcome traditional organizational management, a conservative culture, and barriers imposed by norms.

Organizational Culture

Organizational culture is understood as an organization’s set of common values, ideas, customs, and beliefs that are learned, discovered, or developed as a response to the needs posed by the surroundings or the environment (Schein, 1988). We may define organizational culture as a learned product—emerging from interactions—that accounts for constructions of meaning and sense that take place in every organization.

According to Schein (1988), organizational culture performs two main functions: allowing an organization to adapt to external phenomena and keeping its members together. Culture works like the social glue that binds those who belong to an organization (González-Limas et al., 2018); we can infer from this that organizational culture helps integrate an organization’s various intangible assets, and it is a crucial element because it influences thinking and behavior as well as the goods or services that each organization can produce.

An organization’s culture can be seen as its very soul (Gaus et al., 2019) insofar as it allows the organizational strategies, processes, structures, and interactions not only to function properly but to function in a way that differs from other organizations. Since culture is bound to the individuals that belong to an organization and the interrelationships among them, culture manifests itself in an organization’s way of doing things, as well as in the way that its members interact and communicate, in its processes, in the set of norms that frame relationships and the shared values and beliefs that have meaning for the organization’s members (Hatch, 1993; Martin, 1992, 2004; Smircich, 1983), and in communications, relationships, and the exercise of power and authority.

Innovation

Innovation refers to new ways of developing useful products, processes, or services (OECD, 2018) by using creative or novel ideas (Schumpeter, 1934) to make economic gains while responding to society’s needs (Drucker, 2014). Daher (2016) states it is the organization’s capacity to initiate, develop, or implement new ideas, products, or technologies to expand the market and increase its competitiveness.

According to Daher (2016), innovation is the organization’s capacity to initiate, develop, or implement new ideas, products, or technologies to expand the market and increase its competitiveness. Moreover, Boyd (2020) posits that innovation is the main and most important source of growth and development, stressing that it is possible to stimulate creativity—as an element that is connected (and indispensable) to innovation—through the use of tools that help attain new ideas and thinking within the limitations of business work in terms of reach, time, pertinence, and resources.

Understanding innovation as an ability and as a competitive asset requires to including existing relationships between innovation and organizational culture (Sadegh & Ataei, 2012) and, as Azeem et al. (2021) state, innovation can be looked upon in favor if the organization has some specific characteristics in its organizational culture.

Relationship Between Organizational Culture and Innovation

Many studies, such as the ones done by Freeman (2002) and Arocena and Sutz (2003), have focused on analyzing the way in which the capacity for innovation is related to a group of characteristics that can favor or hinder its implementation, development, and maintenance. Some of these characteristics are exogenous, or come from the environment, and are related to science and technology systems, policies and norms focused on development, systems of innovation, and educational and technological environments that end up affecting both organizations and those who are a part of them. Some more of those characteristics, according to Lin et al. (2012), are endogenous, and among them are highlighted organizational culture, the conditions of the labor environment, the communications ways and social interaction, the styles of leadership, the management processes and the human resources management (Lau & Ngo, 2004; Pister, 2021; Cai et al., 2021).

However, Sandoval (2014) emphasizes that the fundamental challenge is to sustainably maintain a culture that facilitates the changes and learnings required by innovation—understanding the need for change as an element that creates value. For Murray and Steele (2004), to create and share an innovation-oriented culture requires to framing, socializing, and positioning a group of policies, values, and practices that result in learning and sharing ideas successfully, ideas that come from different levels and areas among the organization. On the other hand, for Janssen (2000), this culture implies identifying the human potential within the organization in order to recognize and stimulate the critical sense, the ability to make proposals, the exercise of creative thinking, and to take errors as reflexive opportunities; in this way, the development of the workers’ innovative behavior is strengthened regarding the creation, promotion, and application of new ideas, products, processes, procedures, and methods at work, in order to boost their results (either individual or of a specific area). This also helps to develop better adaptability and flexibility skills among the organization (such as leadership, motivation, and human resources management) in order to be better suited to adapt to the changing conditions of the environment.

Morales and León (2013) argue that an enterprise can “have the best innovation culture, but if it does not have a robust process, it will not go very far. On the contrary, the enterprise can have the best innovation process, but if its people do not live the passion for innovation or are unwilling to question the status quo, take risks and try new things, the best process will not take it very far either.” (p. 109).

In turn, González (2001) states that beliefs must be transformed to favor innovation and combat the self-protectiveness of organizational traditions. As stressed by Felizzola and Anzola-Morales (2017), a culture that favors innovation integrates creativity and a knack for risks, merges strategy and organizational structure, and fosters problem-solving among organization members in different ways than business as usual. To successfully implement an innovation culture, the empowerment of collaborators and the presence of an allied and facilitating leader are fundamental (Amar & Juneja, 2008).

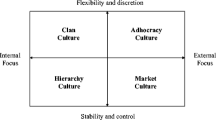

The Organization as an Environment that Favors Innovation

This approach prioritizes organizational efforts to facilitate the implementation of innovation over the inherent capacities of collaborators. Martins and Martins (2002) contend that, for many organizations, change is inevitable. In this sense, organizational leaders seek to build institutional frameworks that integrate creativity and innovation as basic cultural values within an organization. Martins and Terblanche (2003) back this organizational approach and hold that even though organizations are making efforts to implement creativity and innovation in some of their processes, conflictive situations may arise when there is not an adequate culture. Hence, they state that culture integrates and coordinates the behavior of collaborators while regulating how collaborators make use of an organization’s resources. From this perspective, the features shown in Fig. 1 influence a culture that favors innovation (Martins & Martins, 2002).

Source: Martins and Martins (2002)

A model for the implementation of innovation in organizations. Martins and Martins’ version.

Organizational culture appears as an element that links the implementation of innovation with an organization’s strategic objectives while providing suitable values for the introduction of innovation and a positive climate for its development (Felizzola & Anzola-Morales, 2017); moreover, organizational culture facilitates change processes and turns innovation and creativity into key elements of an organization’s success and competitiveness (Martins & Martins, 2002). Successful organizations are those who have managed to absorb innovation into their organizational culture and managerial processes (Martin & Terblanche 2003; Sharifirad & Ataei, 2012).

Individuals as the Driving Force Behind Organizational Innovation

This perspective centers the success of innovation on the talent, capacities, motivations, and values of an organization’s workforce. McLean (2005) and Khazanchi et al. (2007) affirm that innovation fructifies more easily in structures that recognize, value, and empower an organization’s members.

Thus, González (2001) proposes changing innovation beliefs through success stories within organizations or enterprise areas; using “vivid” communication to involve collaborators in the attainment of goals; using a leadership style of moderate and flexible control to align the desires and intentions of collaborators with the organization’s strategic objectives; forming multidisciplinary and heterogeneous workgroups during the idea generation stage—while more homogeneous and cohesive groups can be created for the implementation and development of ideas; empowering collaborators with autonomy, expanding the outreach of positions, and giving relevant meaning to their functions and roles to keep them motivated; and focusing goals on learning and self-learning and the increase of the collaborators’ competency and performance, instead of basing results on assessments and technical skills.

Dombrowski et al. (2007) identified the following eight characteristics present in innovative organizations: innovative mission and vision; democratic communication; safe work spaces and environments; flexibility of functions; collaboration between different staff members and work teams; expansion of boundaries (empowerment and laboral autonomy); incentives; and leadership. However, these characteristics are not always present in organizations, nor can be generated in the same way or from the same mechanisms as other organizations can. Additionally, Amar and Juneja (2008) stress that innovation comes from the implicit knowledge of collaborators. According to the authors, part of the construction of an innovation-oriented organizational culture relies on selecting workers and developing their competencies through what they call “knowledge pockets.” They argue that the interaction between the implicit knowledge in these “pockets” and the (mainly socio-cultural) context leads to the development of creative and divergent thinking that ultimately promotes innovation.

For Amar and Juneja (2008), the sum of knowledge, culture, and trust-related social capital yields creative thinking—which they consider to be the basis for the entire innovation process in organizations (see Fig. 2).

Source: Author’s own using data from Amar and Juneja (2008)

A model for the implementation of innovation in organizations. Amar and Juneja’s version.

A Joint Effort Between Organization and Collaborator

This final approach understands the implementation of creativity and innovation as a joint effort between the actions taken by the organization and the collaborators. Jemkins (2014) holds that although there is a clear influence of organizational culture on the implementation of creativity and innovation in organizations, there is no conclusive evidence of an ideal configuration of culture.

In turn, Ahmed (1998), Morales and León (2013), and Afsar and Umrani (2020) contend that the essential elements for building an innovation-oriented organizational culture are:

-

Vision and leadership for innovation: leaders must communicate, inspire, and challenge other organization members with their vision while leading by example in performing innovative actions.

-

Questioning the status quo: a climate where the way things are done in an organization is questioned must be fostered while highlighting best practices and promoting the creation of new ideas.

-

Environment and resources: organizations must set aside space, time, and strategies for the development of competencies involved in creativity, the search for opportunities, and the implementation of innovation initiatives.

-

Talent and motivation: enterprises do not innovate. People do. It is fundamental to attract, retain, develop, incentivize, and recognize the innovative efforts of collaborators while assigning challenges and projects to those that are the most interested.

-

Experimenting and taking risks: organizations must reduce the perception of fear related to proposing ideas while promoting experimentation with new ways of doing things and fault tolerance—insofar as they lead to organizational learning.

-

Thought diversity: organizations must favor multidisciplinarity and heterogeneity in work teams to promote the creation of connections—internal or external—while enriching perspectives and knowledge.

-

Collaboration: all areas of the organization need to get involved in innovation processes. Thus, it is important to promote collaboration among departments, the formation of transversal groups, and an atmosphere of trust and respect.

Closing the Gap Between Innovation and Organizational Culture

Building paths and bridges between the existing organizational cultures and the proposals included in each of these components through concrete actions are the way to raise awareness in organizations about the importance of innovation without neglecting the fragile balance between the empowerment of collaborators, the flexibility of processes, and the control over these efforts (Naranjo et al., 2011). In this sense, Pisano (2019) identified an existing tension between the openness and flexibility that innovation requires and the orientation toward eradicating incompetence, keeping a rigorous discipline, communicating openly, taking individual responsibility, and embodying strong leadership.

Innovation must be taken as an interactive learning process within sociocultural and organizational contexts where transforming elements and variables coexist. Innovation accounts for a process where different types of knowledge are accumulated and combined to create a process of change—framed by culture—with technical and social components (Máynez-Guadarrama et al., 2012).

According to Anzola-Morales (2019), both innovation and change are concepts that have undergone countless modifications that speak of a migration from a macro conception centered on the analysis of elements outside of the organization to a microlevel analysis where most organizational behavior can be explained from elements that pertain to the organization, its institutional context, and its internal and symbolic dynamics. Therefore, innovation becomes an element that catalyzes a set of reconfigurations of organizational elements that require collective actions.

On the other hand, if innovation becomes a process of change, it is necessary to acknowledge that transformation processes can conflict with the beliefs, attitudes, habits, routines, and behavior patterns commonly accepted within an organization—which can be seen as the memorization of an organization’s accumulated knowledge that makes part of the organizational culture.

An Educational Outlook

The Perception of Innovation Among High Education Institutions

Cultural studies are many and complex. Aktouf (2002) and Anzola-Morales et al. (2017) state that it is within this very complexity that researchers distort the concept of “culture” itself, leading to results that do not consider the elements that must be studied to define an adequate culture for innovation in organizations, which leads to believe that innovation in higher education is mainly related to technological development (Zhu, 2015). In this regard, Cardenas et al. (2017) state that innovation helps to integrate cutting-edge technology into the teaching–learning process—the latter being a growing trend that is now focused on new areas and uses such as gamified education (educating through ludic and practical digital experiences), digital empowerment (technology in classrooms as a tool to facilitate learning), and the merging of pop culture into academia (TrendHunter.com, 2018).

However, aside from education trends involved in this technological component, the element of organizational culture in higher education institutions must be analyzed since it is one of the major barriers to adopting new strategies, technologies, and innovation processes. Cárdenas et al. (2017) argue that the implementation of innovation in higher education also must:

-

Increase the quality of education and improve all organizational areas since it favors the solution to most of the problems faced by higher education institutions at the local level.

-

Transform multiple higher education areas (such as teaching and management processes, the availability of learning resources, and new learning programs and methods, among others).

Kezar and Eckel (2002) contend that there is no theoretical framework that refers specifically to innovation-oriented culture in higher education organizations; instead, the global concepts of innovation culture that were developed in business settings are applied, and so this defines how higher education institutions are often seen as enterprises (a situation that leads to countless problems). For instance, Schmitz et al. (2016) concluded that terms like “innovation” and “entrepreneurship” have not been defined with precision, which hinders their proper implementation, measurement, and focusing; specifically, innovation has gained recognition in university networks that promote environments that boost innovation.

Along these lines, higher education institutions must implement innovative models that overcome the adoption of new technologies as the only method to respond to the new demands (of the environment and the organizational sphere). Copying other models also does not guarantee the sought-after success, so it is necessary to create one’s own model to develop an innovation culture in every organization (Kezar & Eckel, 2002).

The Latin-American Context of Innovation in High Education Institutions

Although innovation can become a strategic ally in the face of challenges and opportunities encountered by education organizations, it is worth asking if Latin American education institutions are ready for innovation. Traditional universities often strongly resist change and are slow and reactive when it comes to implementing environmental trends. In the context of Latin America, Morales and León (2013) show how some cultural “vestiges” in society affect the implementation of innovation:

-

We are stuck in the past: if things have worked before, we believe it is not necessary to change the way we do them.

-

We are too respectful of hierarchies: the boss knows everything and imposes the way of doing things; the process is above everything else.

-

We lack creative autonomy: we believe that everything that comes from outside is better, and that only other countries are capable of innovating and thinking big.

-

We are short-sighted: daily tasks absorb all the efforts of organizations. Investment returns must appear quickly; otherwise, a project or novel idea is not considered useful.

-

We are afraid of success: organizations are selfish and would rather prevent the success of other organizations than work with them and share victories.

Hasanefendic et al. (2017) state that innovation in higher education institutions is determined by the changes in their regional, political, and economic context as well as the normative restrictions in every institution. García (2018) posits that, due to the recent free trade agreements between Latin-American and developed countries, education started to be traded like any other service—following the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS)—given its high profitability and the benefits this brings to developed countries. On the other hand, in developing countries, education and research investments are not aligned to actual needs, for they prioritize coverage over quality and lead to the establishment of an education system that is highly hierarchized and distant from the contextual conditions.

One of the negative consequences of this phenomenon lies in the threat posed by the potential incorporation of higher education institutions in the country, the brain drain catalyzed by the mobility of students, professors, and researchers, and the possible decrease in education quality (García, 2018).

Methodological Aspects

This research followed a combined approach: qualitative and quantitative methods are seen as complementary so data obtained through the use of qualitative and quantitative tools can be validated (Jick, 1979). The desired research level is of the explanatory kind. This research was developed in three phases: the diagnosis; the characterization of organizational culture; the proposal of a model for innovation-oriented culture.

Population and Sample

The object of this study was a university faculty comprising 111 members. The random, non-stratified participation involved 43 individuals of this finite population, represented by 24 men and 19 women who had varying employment periods (less than a year, 6.98%; between 1 and 5 years, 41.86%; between 5 and 10 years, 30.23%; more than 10 years, 20.93%) and the following positions (adjunct professors, 46.51%; part-time professors, 13.95%; full-time professors, 11.63%; administrative staff, 27.91%). The sample is representative of a 10% sampling error and a 95% confidence interval. On the other hand, in order to get more information regarding the perceived relationship between organizational culture in the faculty and the required developments for innovation, four interviews were made with collaborators in the faculty: two full-time professors, an adjunct professor, and an administrative staff member.

Data Gathering Techniques and Instruments

Given the combined approach followed in this research, interviews were used as a qualitative data-gathering technique. As for the quantitative approach, the Inventory of the Organizational Culture in Education Institutions (ICOE) (Marcone and Martín 2003) and Bridges’ test (TB) (Bridges, 2000) were applied (see Annex 1 and 2, respectively).

Initial data gathering was followed by a characterization of the current state of the organizational culture, which was compared with the ideal components that the authors state must be present in an organizational culture that is prepared for innovation.

Regarding this characterization of innovation-oriented organizational culture, we took into account the three phases proposed by Lin et al. (2012): the intention of innovation, the process of innovation, and the results of innovation. Also, the characteristics proposed by Tierney (quoted by Kezar & Eckel, 2002), Martins and Martins (2002), and the four second-level factors identified by Marcone and Martín (2003) in the ICOE were used as a reference to make the necessary changes to the components that were characterized in the previous phase.

Descriptive Analysis of the Instruments

Bridges’ test and the ICOE can analyze two different components of organizational culture. The first looks for the organization’s profile and its relationship with the features that belong to an innovating profile, whereas the second look for the cultural perspective of organizations in the education sector.

Bridges' test

This test groups 36 questions in pairs of responses that are graded using a Likert scale from 1 to 4 to identify the profile of organizations between 16 possible options (see Table 1); these options arise from the combination of pairs of features, thus: extrovert or introvert, sensor or intuitive, thinker or feeler, judger or perceiver. It is important to note that the extrovert, intuitive, feeler, and perceiver (ENFP) profile is associated with an organization that is more attuned to innovation.

The identified profile for the faculty is introvert, intuitive, feeler, and judger (INFJ) (see Fig. 3).

Of the four personality features, in the Extroversion–introversion range, the faculty’s organizational culture seems to be divided between an outward look, seeking to focus on the market behavior and competition (extroversion), and an inward look focused on its own resources, the deanship, and the culture of the university (introversion) to which it belongs. In any case, the scores are slightly inclined toward introversion—a feature that is not associated with the innovative profile.

From the sense: Intuition perspective, the faculty has an intuition-oriented approach: a holistic view to identify opportunities in situations and project a vision into the future; this component coincides with the profile that is associated with innovative organizations.

In the thinking: Feeling category, the results show that the faculty is focused on feeling. This suggests the prevalence of the common good, the promotion of creative thinking, and personalized education processes; this approach also matches the profile associated with innovative organizations.

Lastly, in the judgement: Perception sphere, the decisions related to the outside world are taken firmly, clearly, and hierarchically; this is directly related to the judgement feature a perspective that is linked to innovation.

ICOE

The Inventory of Organizational Culture for Education Institutions evaluates several aspects of organizational culture by arranging different groups of questions—62 in total—into first- and second-level factors (see Fig. 4).

Additionally, a preliminary diagnosis was carried out to analyze each question separately. It is important to note that, after applying descriptive statistical processes to the results and grouping the responses based on the demographic characteristics of the sample, the only demographic variable that showed significant differences was the “type of employment relationship with the faculty.” The other two variables (gender and employment period) had a homogeneous behavior in the responses. Thus, the results shown comprise only those affected by the variable “type of employment relationship with the faculty.”

-

(i)

General

To identify the components of the ICOE questionnaire with the greatest response variations, a descriptive statistical process of variability was used. Following a maximum 25% dispersion or variability percentage (that is to say, assuming as acceptable variabilities those below 25%), the questions noted in Table 2 were found to have a variability greater than or equal to 25%, and in this case, the percentage of variability is understood as the relationship between the standard deviation and the mean obtained for each response.

Table 2 Responses with variability greater than or equal to 25% Question 45 addresses periodical meetings to keep track of goals; broadly speaking, questions 14, 15, 51, and 56 involve fault tolerance, support and motivation from managers, communication as the foundation of team cohesion, and the recognition of efforts. Even though these components have relatively positive behavior, they may require reinforcement actions to close the variability gap.

-

(ii)

First-Level Factors

These factors comprise groups of questions oriented toward defining the behavioral profile of organizational culture; there are 14 first-level factors, as shown in Fig. 4. A descriptive statistical process was applied to identify the behavior of these factors in the faculty. Starting from a 25% tolerance (i.e., variability below 25% was defined as normal), the predominant profile was ESL (Equity in School Life, a profile that values the pedagogical relationship and everyday life in the institution); also, the profiles with the highest variability were OEN (Organizational Entropy and Negentropy, a profile that incorporates the relationship between the rumors that circulate within an organization and the records and pieces of evidence that account for the organization’s evolution) and CHES (Communication and Historical Evolution of the School, a profile that emphasizes communication and graphical records as channels that portray the organization’s evolution) with 25 and 24 percent, respectively.

We found that the OEN profile shows a high variability among the groups that differ on the type of employment relationship. To identify the cause of this variability, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) statistic process was applied to the scores for the questions that make up the OEN profile; the behavior of part-time and full-time professors is remarkable in this profile: their evaluations per aspect are the most negative from the sample.

-

(iii)

Second-Level Factors

The 14 previously described factors can be grouped into four new factors. These factors seek to probe the general perception of organizational culture in terms of leadership, communication, effort recognition, and human relationships. In general, the results do not show a remarkable variation.

However, the findings related to first-level factors show that it is important to delve deeper into these results. After applying the descriptive statistic process of variability based on the type of employment relationship with the faculty, we found again that full-time professors gave the lowest gradings. Nevertheless, it must be noted that adjunct professors also graded the effort and communication factors with a satisfactory grade—below 4.0.

We can conclude that the main components that have room for improvement are those related to supporting and recognizing efforts, building and communicating a transparent historical memory that accounts for the evolution of the faculty, mitigating rumors through written records, and strengthening communication both between managers and professors and between professors themselves.

Full-time professors were identified as the members that disagree the most with the current state of the previously described components. In some of these components (for instance, effort recognition and strengthening of communication channels), part-time professors and adjunct professors also concur with full-time professors.

Correlational Analysis Between the Instruments

After analyzing the results for every instrument separately, a correlational analysis was carried out to identify possible links between the profile obtained through Bridges’ test and the profiles that have room for improvement that were identified in the ICOE. A statistical significance study was undertaken to identify the questions where there is a high degree of relation; answers with considerable significances of 0.05 (95% confidence) and 0.1 (90% confidence) were taken into account (see Table 3).

This correlation supports the findings related to each instrument’s analysis. Striking discrepancies recur in both significances regarding effort recognition, clarity, and relevance of communication systems in the faculty, and the socialization of the faculty’s history and achievements as elements to justify changes and pedagogical innovation. Other key components that appear—mainly in the 90% significance level—are the leadership style and behavior of managers in terms of exemplary leadership, the empowerment and appraisal of others’ opinions, the attention to optimal work conditions, and fault tolerance. It must be noted that all these elements are essential when implementing innovation processes in an organization.

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Faculty’s Organizational Culture Concerning Innovation

After the previously described diagnosis of the faculty’s organizational culture—and comparing it to the cultural ideals for innovation that were presented—the following matrix emerges:

Two conclusions can be drawn from this analysis. Firstly, though the faculty has some adequate elements for the implementation of innovation (such as managers’ support and welcoming of new ideas, an atmosphere of camaraderie, multiple communication channels, and human resources with varied kinds of knowledge), the administrative approach oriented toward results and solving everyday problems, the difficulty in creating interdisciplinary teams, and the professors’ lack of motivation—either due to the lack of effort recognition or the excess of assigned functions—negatively impact the development of innovation projects.

Secondly, some elements harm specific groups of professors. For example, part-time and adjunct professors feel excluded from many of the meetings organized by managers, and they also state that communication channels are not effective with them, while full-time professors complain about the lack of coordination in the development of projects with part-time professors.

Findings and Insights

By analyzing the strengths and weaknesses identified after making a correlation between the data we gathered and the different characteristics and values that an ideal innovation-oriented culture possesses according to the literature review, we identified eight main components that an innovation-oriented organizational culture for the faculty studied should foster: environment; resources; risk-taking and fault tolerance; vision and leadership for innovation; strategic thinking; talent, motivation, and thought diversity; communication and collaboration; autonomy and empowerment (as shown in Table 4).

These eight components can be grouped into three levels or cores (personal, administrative, and external) to identify the key components that lack coordination and promote efforts and actions to adjust them.

It is important to note that for innovation-oriented organizational culture to be built successfully and remain sustainable through time, adjustments and changes should be stimulated first in the personal core, to be extended later to the administrative core, and, eventually, to influence the external core.

The personal core is related to the most inner part of the faculty and brings together the three components that were identified as particular to each individual that belongs to the organization: talent, motivation, and thought diversity; communication and collaboration; and autonomy and empowerment. These components involve all the talents, capacities, and freedom of action that each individual has within the organization. The balance of these components results in an individual that is aligned with innovation processes.

The administrative core is related to the managerial and structural part of the faculty and brings together the components related to the organization’s vision and mission, either of the enterprise as a whole or one of its areas: vision and leadership; decision-making and fault tolerance and strategic thinking. The balance between these components results in an organization whose strategic vision is aligned with innovation.

Finally, the outer core is related to the external environment of the faculty (regulations, geopolitical restrains, economical resources, among others) and may or may not be susceptible to adjustment. However, innovation can start from a set of restrictions imposed by the environment and resources, so it is more important to prioritize balance at the inner level of the model to later align the middle-level components.

These three cores can be understood as if imbued within each other, as shown in Fig. 5.

Inner Core: The Personal Level

The personal core alludes to the components of each faculty member; these components are considered important for innovation. Moreover, the diagnosis showed that these are the most affected components in the faculty. The component “autonomy and empowerment” is well balanced toward innovation. However, the components related to “talent, motivation, and thought diversity” and “communication and collaboration” are not.

The diagnosis showed that faculty members have multidisciplinary talents and types of knowledge, as well as a great diversity of thought, perspectives, and creativity when it comes to proposing and executing projects for the faculty. The motivation area is the one that shows problems: the lack of effort recognition, lack of awareness of past achievements, bureaucratic and administrative processes that slow down the development of projects, and little sense of belonging regarding the faculty’s vision.

The component related to communication and collaboration is the one that is the most far from ideal regarding innovation. Though there are several communication channels in the faculty, professors do not use them to communicate among themselves about the projects that they are developing; in fact, full-time professors do not know the projects of their peers or the projects being developed by part-time professors. Additionally, adjunct professors are uneasy, for they feel excluded and segregated, which undermines their motivation and ultimately leads to the misaligned behavior of the described component.

Middle Core: The Administrative Level

The components related to the faculty’s strategic vision are found at the administrative core; these components are linked with innovative organizations. Of the components that comprise this level (“vision and leadership,” “risk-taking and fault tolerance,” and “strategic thinking”), “strategic thinking” is the one that is less optimal for innovation; managers and the dean’s office pay considerable attention to the fulfillment of metrics, the results of everyday tasks, and the efficiency of economic resources (for example, by assigning multiple functions to several members). Likewise, the faculty only has one postgraduate program, is in the process of creating another one, is working on the design of some MOOCs, and is undertaking the redesign of the undergraduate program’s syllabus to adjust it to new quality standards. This evidence shows a reactive approach in the faculty—a position that is not linked to innovation.

It is important to note that the “vision and leadership” and the “risk-taking and fault tolerance” components are slightly unbalanced toward innovation. Though the efficiency-oriented vision, the attention to metrics and objectives, and the control-based leadership style have led to the faculty’s growth in recent years, these factors are currently a source of uneasiness among professors. They argue that this leadership style prevents them from carrying out their projects and administrative decisions with more efficiency; furthermore, the amount of assigned functions forces them to focus on solving everyday problems instead of looking for alternatives and developing their projects.

The diagnosis showed that, though the faculty understands that changes entail risks, such risks must be calculated. In this sense, fault tolerance in the faculty has various shades: the leadership style oriented toward control and metrics makes failure punishable, but failure can be tolerated when some objectives are not met if the project is new or it has the potential to yield outstanding results.

Outer Core: The External Level

Though it is not entirely controllable and adjustable to the faculty’s interests, the external organizational core exerts a direct influence on the organizational core. At this level, two components are found: environment and resources.

According to the full-time professors, there are bureaucratic and economic barriers that limit the outreach of projects designed by the faculty. However, these barriers escape the management that can be undertaken from the faculty since they are restrictions, protocols, and measures that are adopted by the university itself. From another perspective, the faculty has several resources (human resources, infrastructure, teams that specialize in media, and a network of contacts) that give it the potential to conceive and develop projects without depending on limited economic resources.

Final Thoughts

These cores contain one another, and so the outer core contains the administrative core, and the administrative core contains the personal core. However, it is essential to prioritize adjustments at the personal core to build and cultivate a culture that fosters innovation; according to Amar and Juneja, “organizations do not innovate—subjects do” (2008). This core approach for the faculty’s organizational culture is the first step to understanding how its members’ values, knowledge, interactions, and work are linked together. This approach also helps to quickly identify which component needs priority adjustment to build together an innovation-oriented organizational culture.

Along this line, it is very important to stress that not every innovation process regarding high education organizations implies the adoption of new technologies. By strengthening some or all the components shown previously—such as leadership, communication, and strategic thinking, just to name a few, individuals and areas within the organization can improve their processes and the design of programs, strategies, and different educational products with the resources at hand.

In the Colombian context, at the time of the publication of this article, there were not many studies done to analyze innovation-oriented culture in high education institutions. This article adds to the efforts to study the relationship between culture and innovation in that kind of organization.

Regarding the studied faculty, it shows potential intention for innovation—for instance, by designing and creating new programs and redesigning the current ones it has; this potential can be used in order to allocate resources and efforts to strengthen the weak components identified that are related to an innovation-oriented organizational culture or to innovate in administrative processes, pedagogical components, and strategic vision.

It is important to note that the university in which the studied faculty is located does not exist in an area specifically built to develop abilities and characteristics related to innovation. In this regard, this study pretends to be an initial step to open the discussion regarding the importance of innovation in high education organizations, both as a whole and its faculties and departments, making clear that there is not a specific approach that works equally to every institution and as such copying other successful approaches and models do not necessarily mean that they will work as well as intended.

Finally, the correlation made by crossing the gathered data by using both the ICOE and the Bridges’ Test was instrumental in identifying key insights and findings that let us come up with a characterization in depth, that in turn helped us to make the three-core approach for the faculty’s organizational culture. We hope that more studies of innovation-oriented organizational culture regarding high education institutions are made; in this effort, we provide the instruments used in this study as annexes, leaving an open path for this kind of research.

Data Availability

All data analyzed in this study is available for review. If interested, please write an email to the authors, stating your interest in reviewing the data and the purpose of your review.

Material Availability

All data analyzed in this study is available for review. If interested, please write an email to the authors, stating your interest in reviewing the data and the purpose of your review.

References

Afsar, B., & Umrani, W. (2020). Transformational leadership and innovative work behavior The role of motivation to learn, task complexity and innovation climate. European Journal of Innovation Management, 23(3), 402–428.

Ahmed, P. (1998). Culture and climate for innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 1(1), 30–43.

Aktouf, O. (2002). El simbolismo y la cultura organizacional. De los abusos conceptuales a las lecciones de campo. Revista Ad-Minister, 1, 65–94.

Anzola-Morales, O., Marín-Idárraga, D. & Cuartas, J. (2017). Fundamentación teórica de la cultura, la estructura y la estrategia de la organización. Referentes para el análisis y diseño organizacional. Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia.

Anzola-Morales, O. (2019). Lo tecnológico, la cultura digital y los procesos de cambio. In N. Velásquez, M. Colin & O. Hernández (comps.). Las tecnologías de información como base de la competitividad en las organizaciones, (pp. 113–144) Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia.

Amar, A., & Juneja, J. (2008). A descriptive model of innovation and creativity in organizations: A synthesis of research and practice. Knowledge Management Research y Practise, 6(4), 298–311.

Arocena, R., & Sutz, J. (2003). Subdesarrollo e innovación: Navegando contra el viento. OEI / Cambridge University Press.

Azeem, M., Ahmed, M., Haider, S., & Sajjad, M. (2021). Expanding competitive advantage through organizational culture, knowledge sharing and organizational innovation. Technology in Society, 66, 101635.

Boyd, D. (2020). Explore the method: Getting started. Retrieved July 2020, from https://drewboyd.com/getting-started/

Bridges, W. (2000). The character of organizations: Using personality type in organization development. Davies-Black Publishers.

Calderón, G., & Naranjo, J. C. (2007). Perfil cultural de las empresas innovadoras. Un estudio de caso en empresas metalmecánicas. Cuadernos De Administración., 20(34), 161–189.

Cai, W., Gu, J., & Wu, J. (2021). How CEO passion promotes firm Innovation: The mediating role of Top Management Team (TMT) creativity and the moderating role of organizational culture. Current Psychology, 1–17.

Cárdenas, C., Farías, G., & Méndez, G. (2017). ¿Existe relación entre la Gestión Administrativa y la Innovación Educativa?. Un estudio de caso en la educación superior. REICE Revista Iberoamericana Sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio En Educación, 15(1), 19–35.

Daher, N. (2016). The relationship between organizational culture and organizational innovation. International Journal of Business and Public Administration, 13(2), 1–15.

Dombrowski, C., Kim, J. Y., Desouza, K. C., Braganza, A., Papagari, S., Baloh, P., & Jha, S. (2007). Elements of innovative cultures. Knowledge and Process Management, 14(3), 190–202.

Drucker, P. (2014). Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Routledge.

Felizzola, Y., & Anzola-Morales, O. (2017). Proposal of an organizational culture model for innovation. Cuadernos De Administración, 33(59), 20–31.

Fernández, E., Montes, J., & Vásquez, C. (1998). Los recursos intangibles como factores de competitividad de la empresa. Dirección y Organización, 20, 83–98.

Freeman, C. (2002). Continental, national and sub-national innovation systems complementarity and economic growth. Research Policy, 31(2), 191–211.

García, C. (2018). La mercantilización de la educación superior en Colombia. Revista Educación y Humanismo, 20(34), 36–58.

Gaus, N., Tang, M., & Akil, M. (2019). Organisational culture in higher education: Mapping the way to understanding cultural research. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 43(6), 848–860.

González, A. (2001). Innovación organizacional. Retos y Perspectivas. Cuba: CIPS. Retrieved October 8, 2018, from http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Cuba/cips/20120823042336/gonza4.pdf

González-Limas, W., Bastidas-Jurado, C., Figueroa-Chaves, H., Zambrano-Guerrero, C., & Matabanchoy-Tulcán, S. (2018). Revisión sistemática de las concepciones de cultura organizacional. Universidad y Salud, 20(2), 200–214.

Hatch, M. (1993). The dynamics of organizational culture. Academy of Management Review, 18(4), 657–693.

Hasanefendic, S., Birkholz, J., Horta, H., & Van der Sidje, P. (2017). Individuals in action: Bringing about innovation in higher education. European Journal of Higher Education, 7(2), 101–119.

Issa-Fontalvo, S. M. (2017). Habilidades del liderazgo para una cultura de innovación en la gerencia de las universidades del distrito de Santa Marta. Revista Academia y Virtualidad, 10(1), 56–67.

Jamrog, J., Vickers, M., & Bear, D. (2006). Building and sustaining culture that supports innovation. Human Resources Planning, 29(3), 9–19.

Janssen, O. (2000). Job demands, perceptions of effort-reward fairness and innovative work behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73(3), 287–302.

Jasso, J., Del Valle, M., & Núñez, I. (2017). Innovation and development: A revision the Latin American thought. Academia. Revista Latinoamericana De Administración, 30(4), 444–458.

Jenkins, M. (2014). Innovate or Imitate?. The role of collective beliefs in competences in competing firms. Long Range Planning, 47(4), 173–185.

Jick, T. (1979). Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: Triangulation in action. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 602–611.

Kezar, A., & Eckel, P. (2002). The effect of institutional culture on change strategies in higher education. The Journal of Higher Education, 73(4), 435–460.

Khazanchi, S., Lewis, M., & Boyer, K. (2007). Innovation-supportive culture: The impact of organizational values on process innovation. Journal of Operations Management, 25, 871–884.

Lau, C., & Ngo, H. (2004). The HR system, organizational culture, and product innovation. International Business Review, 13(6), 685–703.

Lin, Ch., Yeh, J., & Hung, G. (2012). Internal impediments of organizational innovation: An exploratory study. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 3(2), 185–198.

Marcone, R., & Martín, F. (2003). Construcción y validación de un inventario de cultura organizacional educativa (ICOE). Psycothema, 15(2), 292–299.

Martin, J. (1992). Cultures in organizations: Three perspectives. Oxford University Press.

Martin, J. (2004). Organizational Culture. Research Paper Series, 1847, 1–18.

Martins, E., & Martins, N. (2002). An organisational culture model to promote creativity and innovation. Journal of Industrial Psychology, 28(4), 58–65.

Martins, E., & Terblanche, F. (2003). Building organisational culture that stimulates creativity and innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 6(1), 64–74.

McLean, L. (2005). Organizational’s Culture influence on creativity and innovation: A review of the literature and implications for human resources development. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 7(2), 226–246.

Máynez-Guadarrama, A., Cavazos-Arroyo, J., & Nuño-De la Parra, J. (2012). La influencia de la cultura organizacional y la capacidad de absorción sobre la transferencia de conocimiento tácito intraorganizacional. Estudios Gerenciales, 28, 191–211.

Morales, M., & León, A. (2013). Adiós a los mitos de la innovación: una guía práctica para innovar en América Latina. San José de Costa Rica: Innovare.

Murray, M., & Steele, J. (2004). Creating, supporting and sustaining a culture of innovation. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 11(5), 316–322.

Naranjo, J., Jiménez, D., & Sanz, R. (2011). Innovation of imitation? The role of organizational culture. Management Decision, 49(1), 55–72.

OECD. (2018). Oslo manual 2018: Guidelines for collecting, reporting and using data on innovation. OECD Publishing, Paris/Eurostat.

Pisano, G. (2019). The hard truth about innovative cultures. Harvard Business Review, 97(1), 62–71.

Pister, M. (2021). Leadership and innovation. How can leaders create innovation-promoting environments in their organisations? European Journal of Marketing and Economics, 4(2), 42–52.

Prieto, M., Contreras, F., & Espinosa, J. (2020). Liderazgo y comportamiento innovador del trabajador en personal administrativo de una institución educativa. Diversitas: Perspectivas, Psicológicas, 16(1), 25–35.

Sadegh, M., & Ataei, V. (2012). Organizational culture and innovation culture: Exploring the relationships between constructs. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 33(5), 494–517.

Sandoval, J. (2014). Los procesos de cambio organizacional y la generación de valor. Estudios Gerenciales, 30(131), 162–171.

Sharifirad, M., & Ataei, V. (2012). Organizational culture and innovation culture: Exploring the relationships between constructs. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 33(5), 494–517.

Schein, E. (1988). La cultura empresarial y el liderazgo. Una visión dinámica. Plaza y Janes.

Schmitz, A., Urbano, D., Dandolini, G., de Souza, J., & Guerrero, M. (2016). Innovation and entrepreneurship in the academic setting: A systematic literature review. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13, 369–395.

Schumpeter, J. (1934). A theory of economic development. McGraw-Hill.

Smircich, L. (1983). Concepts of culture and organizational analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28(3), 339–358.

TrendHunter.com. (2018). Education Consumer Insights. Retrieved December 2018, from https://www.trendhunter.com/pro/category/education-trends

Zhu, C. (2015). Organisational culture and technology-enhanced innovation in higher education. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 24(1), 65–79.

Funding

This research was self-supported and self-funded by the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

propose a model for innovation-oriented organizational culture in a faculty within a Colombian university.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on University and Entrepreneurial Ecosystems

Appendix

Appendix

ANNEX 1. Inventory of Organizational Culture in Education Institutions (ICOE) (Marcone & Martin, 2003)

This questionnaire aims to understand your perception regarding the organizational culture of the Faculty of Social Communication and Journalism. Please, assign a grade from 1 to 5 the following 62 states, being 1 “I disagree completely;” 2 “I disagree;” 3 “neutral;” 4 “I agree;” 5 “I agree completely.”

-

1.

I believe this faculty offers an environment that motivates students to give the best of themselves.

-

2.

At the faculty, “being on the look” means to be alert to signals and messages that are generated in the pedagogical process and to act accordingly.

-

3.

At the faculty, all ideas that change past educational practices are strengthened periodically and formally.

-

4.

The changes experimented by our faculty, from its beginnings, demonstrate a creative and innovative life.

-

5.

At the faculty, we value the directors’ efforts to create and keep a good communication system with other faculty members.

-

6.

The existence of agile and expeditious communication channels guarantee our work’s success.

-

7.

Directors let us know what is expected from each of us in a clear and explicit way.

-

8.

Work meetings are announced in advance, in such a way that we know, opportunely, the topics that will be addressed.

-

9.

In our university life there is a sequence of events that show a close union of the members.

-

10.

At the faculty, we share the firm commitment to our students’ learning, which drives us toward pedagogical change.

-

11.

By putting innovative ideas into practice, our leaders publicly express their willingness to change.

-

12.

At the faculty, we tell how, thanks to our willpower and work, we have overcome the challenges that pedagogical change implies.

-

13.

We value mistakes as part of our very nature and as a sometimes necessary step for learning.

-

14.

At the faculty, we share the idea that error is deferred success.

-

15.

In this faculty, it is common for directors to hearten us frequently, which encourages us to move forward.

-

16.

In this faculty, every work well done or success of the staff is recorded, carefully and in a timely manner, in their resume.

-

17.

Our history reveals a permanent learning of the faculty members, which has contributed to the current success achieved.

-

18.

In this faculty, the directors support the professors in their work initiatives.

-

19.

Daily conversations reveal our conviction that we will achieve the changes that this faculty requires to move forward.

-

20.

Pedagogical innovation is constantly and publicly supported by directors.

-

21.

Many projects, which at one time seemed unfeasible, have become a reality thanks to our efforts.

-

22.

Opinions about work are well-regarded, no matter where they come from.

-

23.

The search for consensus is the best way to resolve conflicts that originate in the faculty.

-

24.

In this faculty we are used to telling each other things clearly and directly.

-

25.

In the faculty, when there have been differences between professors and directors, positive action has always been taken.

-

26.

In the faculty, the directors value the opinions and feelings of the staff.

-

27.

The management style of directors reveals that they consider professors as responsible and capable of taking on challenges.

-

28.

The directors’ communications clearly reflect what they want to say and do so with deep interest and respect for us.

-

29.

We have photographs that remind us of the various stages of development we have gone through.

-

30.

Directors do not miss an opportunity to demonstrate, with their own example, their commitment to the faculty.

-

31.

At the faculty we act with great security, since we all know the rules of the game that rule our work.

-

32.

The language used between directors and professors is clear and direct, which facilitates tasks and duties.

-

33.

Many rumors circulate in the faculty about the impossibility of achieving the changes that positively transform life in this university.

-

34.

In this faculty it is customary to recognize the efforts of the professors in the educational task.

-

35.

The credibility of directors has been sustained, over time, in the coherence that they have managed to establish between what they say and what they do.

-

36.

At the faculty, the work environment fosters autonomy and authenticity, on a level of equality and respect.

-

37.

Our beliefs are very clearly reflected in the facts of daily life at the faculty.

-

38.

Our students fully identify with the faculty, which is verified in daily life and in their behavior in public events.

-

39.

We can easily reconstruct the history of the faculty by studying the existing documents.

-

40.

In the faculty there is a real concern about the working conditions of all the staff.

-

41.

At the faculty we think that managers are motivated by our good professional performance.

-

42.

When we take action, the directors let us know, clearly and directly, that we have their support.

-

43.

It is customary to promote our students' achievements, no matter how small they may be.

-

44.

At the faculty we are told, clearly and firmly, that continuous effort is the key to success in our teaching work.

-

45.

We meet periodically to review the established goals and determine what we have achieved and what we still need to achieve.

-

46.

At the faculty, stories are told about how, thanks to joint efforts, very difficult goals were achieved.

-

47.

The goals that are being pursued at this university respond to the demands and expectations of the community.

-

48.

In the faculty, the directors encourage the participation of all the staff in the achievement of the objectives.

-

49.

At the faculty, at the beginning of each academic term, the objectives and goals that will guide our efforts are established.

-

50.

The history of our faculty shows us how the established goals have been achieved over time.

-

51.

This faculty works to maintain communication that facilitates the integration and cohesion of the staff.

-

52.

In this university, the professors’ councils constitute instances of study of deep reflection and search for adequate coordination.

-

53.

The constant effort of directors and professors has made it possible to visualize a promising future.

-

54.

An open doors policy allows us to participate equally in university life.

-

55.

In the speeches and acts of university life, the importance of equity is highlighted as a norm of life.

-

56.

In the faculty there is a recognition of efforts and a fair allocation of rewards.

-

57.

In this university, when allocating resources, it has always tried to act with equity.

-

58.

The motto “always do what is right” guides our actions in the daily life of the university.

-

59.

What sets us apart from other universities is the enthusiasm we put into achieving our goals.

-

60.

The instructions and guidelines for students, parents, guardians and the public are clear and precise.

-

61.

In the faculty, before starting a new project, it is customary to create the conditions so that the professors can concentrate on their work.

-

62.

Past events show us that the achievements reached have originated with the constant effort of professors and directors.

ANNEX 2. Bridges’ Test (Bridges, 2000)

This questionnaire aims to identify the innovation profile of the organizational culture present in the faculty. Please rate the following 36 questions from 1 to 4, based on what is specified in each question, where the extreme values (1 and 4) imply that there is a strong point of view, while the average values (2 and 3) imply that the point of view is slightly inclined.

-

1.

Does the faculty pay more attention to the requests of the clients-students or to its internal knowledge on how to work well? – Clients 1 2 3 4 know how to work well

-

2.

Is the faculty better at producing and delivering goods and services or creating new ones? – Producing 1 2 3 4 creating new ones

-

3.

What matters more to the faculty: management systems or people’s dedication to their work? – Management systems 1 2 3 4 people’s dedication

-

4.

What does the faculty like more: to make procedures and policies very clear and explicit or do you prefer to leave people without much detail so that they can work their way within the basic instructions? – Make clear 1 2 3 4 leave without much detail

-

5.

Can employees openly see how decisions are made in the organization or are decisions hidden from top management and appear mysteriously? – Very open 1 2 3 4 very hidden

-

6.

Is leadership based on decision-making, taking into account detailed information on facts and events, or is it based on an approach to the fact or event in a schematic way and in general terms? – Detailed information 1 2 3 4 general terms

-

7.

Is the faculty concerned about fulfilling the roles and functions of people, established effectively, or does it allow people to work based on the full exercise of their talents? – Official roles 1 2 3 4 people’s talents

-

8.

Would you say that the faculty emphasizes rapid decision-making or waits for all points of view, even if this implies delays? – Rapid decision-making 1 2 3 4 delayed decision-making

-

9.

Are decisions made based on market data and facts or rather on internal factors such as the experience and beliefs of the directors and the capacities of the faculty? – Market data 1 2 3 4 internal factors

-

10.

Are the actions of the faculty based on current events and the present, or are they focused more on trends and expectations for the future? – Present 1 2 3 4 future

-

11.

How decisions are really made in the faculty: with the head (moderated with a bit of humanism) or with the heart (supplemented with information)? – Moderated, with the head 1 2 3 4 balanced, with the heart

-

12.

If there is an error in the faculty, is it due to hasty decisions or because many options were kept that delayed the decision? – Hasty decisions 1 2 3 4 too many options

-

13.

In a project or job, do people collaborate naturally from the beginning or do they do it in a forced way and after each one defines the extent of their responsibilities? – From the beginning 1 2 3 4 in a forced way

-

14.

When the changes have already been discussed, what demands more attention: the monitoring of the steps to achieve the objective or the final result and meet the agreed deadline? – Monitoring of the steps 1 2 3 4 final result

-

15.

When it comes to staff issues, what is taken more seriously: policies and rules or individual circumstances and situations? – Policies and rules 1 2 3 4 individual circumstances

-

16.

Are the actions of the faculty based mainly on the priorities and strategies already traced or on the opportunities and signs identified in the market or the environment? – Priorities 1 2 3 4 opportunities

-

17.

Are the actions of the faculty influenced more by relationships with customers and competitors or are they the result of its identity, of following the organizational mission and culture? – Relationships 1 2 3 4 identity/mission

-

18.

Is the faculty better at producing reliable products and services or generating ideas and designs whose results are presumed to be good? – Reliable products and services 1 2 3 4 novelty ideas

-

19.

In the faculty, does the word “communication” mean giving and receiving information or keeping in touch with all the collaborators? – Giving and receiving 1 2 3 4 keeping in touch

-

20.

Does the faculty work by established procedures and rules or does it work and decide mainly as things happen? – Procedures 1 2 3 4 as things happen

-

21.

Is the scope of the faculty determined by the external challenges that are presented to it or by the availability of resources? – External challenges 1 2 3 4 resources

-

22.

Is the form of leadership in the faculty identified more as solid and down to earth or more as intuitive and visionary? – Down to earth 1 2 3 4 visionary

-

23.

Which is more accurate to describe what is expected of leaders: to act according to rational policies and rules or to act according to their sensitivity and sense of humanity? – Rational policies 1 2 3 4 sensitivity and a sense of humanity

-

24.

To deal with situations, does the faculty choose between trying to decide as soon as possible or looking for options? – Decide soon 1 2 3 4 look for options

-

25.

Does the faculty have an open point of view and allow itself to be influenced by the clients-students and the opinion of the employees or does it have a closed point of view and always respond to an already established management system? – Open 1 2 3 4 closed

-

26.

Is action taken more in a practical and efficient way or in an ingenious and inventive way? – Practical way 1 2 3 4 inventive way

-

27.

When you think of “what is right,” do you think more of what is logical and rational or what is human and sensible? – Logical and rational 1 2 3 4 human and sensible

-

28.

Does the faculty in general seek to “hold on to something solid” or “go with the flow”? – Hold on something solid 1 2 3 4 go with the flow

-

29.

In terms of strategy, is the faculty more focused on satisfying the clients-students and competitors or on the maximum use of the capacities of its employees? – Clients and competitors 1 2 3 4 capacities of its employees

-

30.

When there are big changes, does the faculty prefer to do them step by step or all at once and in an integral way? – Step by step 1 2 3 4 integral way

-

31.

Is the structure of the faculty based mainly on the hierarchy and the tasks of the organizational chart or on the relationships of its members? – Based on tasks 1 2 3 4 based on relationships

-

32.

When planning projects, are deadlines followed and delivery dates met or are schedules made flexible and negotiated according to circumstances? – The plan is followed 1 2 3 4 it is flexible

-

33.

Does the faculty seek alliances to work with other organizations or does it prefer to face the market on its own? – Works with others 1 2 3 4 goes on its own

-

34.

Is the faculty better described as clinging to tried and true ways or open to new and uncertain ones? – Clinging to tried ways 1 2 3 4 open to new ways

-

35.

Which word best describes your leader: criticism or motivation? – Criticism 1 2 3 4 motivation

-

36.

Finally, are plans made thinking about the future or are they made living day to day? – Future 1 2 3 4 day to day

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Orozco Arias, J., Anzola Morales, O. Organizational Culture for Innovation: A Case Study Involving an University Faculty. J Knowl Econ 14, 4675–4706 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-022-01069-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-022-01069-9