Abstract

Objectives

Mindful attention deployment has been found to have practical benefits for a range of interpersonal outcomes including prosocial action and emotion. Recently, theory has posited that contemplative training that incorporates mindful attention may enhance intergroup compassion.

Methods

Here, we conduct a selective narrative review, drawing on the Buddhist concept skillful means to ask if mindful attention deployment presents an optimal starting point for intergroup compassion and action.

Results

An interdisciplinary theoretical framework is presented, which suggests that mindful attention dismantles common intrapsychic challenges to intergroup prosociality. Empirical research is described concerning cause and effect relationships between mindfulness and several outgrowths of intergroup prosociality. Specifically, mindfulness promotes basic social cognitive processes that allow intergroup prosociality to flourish.

Conclusions

While this research is promising, to date, the science on this topic has been limited to individual-level outgrowths of mindfulness practice. Discussion focuses on the future of mindfulness research in intergroup prosociality and calls for an integrative approach situating mindful attention deployment within social (and other) psychological interventions to enhance intergroup compassion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Nearly every day we encounter other people’s suffering and needs (Depow et al., 2021), and decades of research and theory suggest that responding prosocially in these circumstances is foundational to personal, social, and collective well-being (e.g., Weisz & Cikara, 2020). The capacity for prosociality is defined broadly herein as emotions, thoughts, and behaviors that are enacted to alleviate the suffering of others (Goetz, et al., 2010). But prosocial responses are not always a given (see Bloom, 2017) and a multitude of situational (e.g., Latané & Darley, 1970), personal (Penner et al., 1995), and cultural/societal factors can inhibit them.

Perspectives on the motivated nature of prosociality are key to understanding how personal, situational, and societal factors constrain and afford kindness toward others. Others’ suffering is often painful to observe and may lead to cognitive or material costs for the self. So, people regulate their prosocial responses by avoiding compassion-inducing situations or stimuli (Cameron et al., 2019; Zaki, 2014). One way that people regulate prosociality is by enacting it preferentially (Kurzban et al., 2015). In many countries, people are divided along social categories (e.g., race, ethnicity, or political affiliation), and are more likely to express empathy and compassion preferentially toward social ingroup members than outgroup members (Cikara et al., 2011). Thus, considerable efforts in the form of social and political movements have encouraged scientific and social interest in increasing compassion in intergroup contexts to reduce prejudice, discrimination, and conflict.

The science of intergroup prosociality has taken an interdisciplinary approach drawing largely from social sciences including psychology, sociology, political science, and economics, to name a few (Zaki, 2014). Over the past decade, scientists have begun to adopt contemplative practices and theory into their research designs and interventions to enhance intergroup compassion (e.g., Chang et al., 2022; Condon & Makransky, 2020; Oyler et al., 2021). For example, most work on this topic has focused on the value of compassion-based meditation practices for enhancing prosocial emotions, attitudes, and behaviors in constrained laboratory contexts (e.g., Kang et al., 2014; Leiberg et al., 2011; Stell & Farsides, 2016). Despite the importance of this research, giving care and compassion to outgroup members is often met with psychological resistance from prospective empathizers and helpers. For example, people may hold antipathy toward outgroup members (Galinsky et al., 2005), which presents a direct challenge to compassion. People may not have encountered similar lived experiences as outgroup members, making it difficult to understand their suffering (e.g., Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002; Singer et al., 2009). Furthermore, explicit appeals to feel empathy for or to increase liking of outgroup members may undermine support for political efforts to achieve equality (e.g., Dixon et al., 2010; Saguy et al., 2009); perhaps liking and empathizing with the outgroup makes it feel as if one has “already done something virtuous,” thereby thwarting restorative justice.

Considering the risks of engendering various types of psychological resistance in intergroup interactions, are there factors that enhance intergroup prosociality in a relatively unobtrusive way? The scientifically under-researched Buddhist concept of skillful means (upaya-kaushalya) may offer another angle on this question. As it relates compassion, skillful means refers to the notion that the behavioral expressions of compassion are context dependent and, accordingly, compassion may be achieved through a variety of means (see Quaglia, 2022). Thus, compassion is not prescriptive of certain actions and what will maximize compassionate outcomes will depend on the factors in any given situation. We suggest that grounding intergroup prosociality interventions in a mindful quality of attention may serve as a skillful means for promoting intergroup prosociality (cf., Berry & Brown, 2017), due to the potential of mindful attention to unobtrusively dismantle common intrapsychic barriers to intergroup prosociality and thereby maximize compassionate outcomes in intergroup contexts.

Interdisciplinary critiques of mindfulness research and mindfulness-integrated interventions have dubbed these approaches “overhyped” or a fad (e.g., Van Dam et al., 2018). As such, one potential danger is that mindfulness might be applied to situations in which it is ineffective, inappropriate, or potentially harmful (e.g., Bodhi, 2011). Indeed, mindfulness-based meditation practices involving receptive attention to present moment experiences are less obviously linked to prosociality on the surface. After all, secularized forms of mindfulness meditation typically lack explicit instruction in ethics associated with contemplative practices (Monteiro et al., 2015).

Going against these current trends in the literature, mindfulness may be counterintuitively well-suited at helping intergroup compassion to grow, specifically via dismantling the factors that engender psychological resistance to intergroup compassion. We selectively review experimental research on mindfulness interventions primarily within the domain of social cognitive psychology, and through the lens of interdisciplinary theoretical models of compassion (i.e., the “empathic attentional set”). In line with this thinking, training in mindfulness meditation has been found to have a practical benefit for a range of interpersonal outcomes including prosocial behavior and emotion, as well as attenuated aggression and antisocial behaviors (see Karremans & Papies, 2017 for review). Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis examining the effects of mindfulness training on intergroup (and other) prosocial behaviors has found reliable small-to-medium mean difference effect sizes as compared to active and inactive controls (CI(g) [0.30, 0.62]; Berry et al., 2020; also see Oyler et al., 2021). Thereafter, we discuss the challenges for future research on this topic, including more pressing societal hurdles for intergroup compassion (Kraus et al., 2012; Piff et al., 2018; Zaki & Cikara, 2015).

A Case for Mindfulness as a Skillful Starting Point in Overcoming Psychological Resistance to Intergroup Prosociality

How is mindfulness a skillful means for intergroup prosociality? Secular mindfulness practices, which are known to enhance mindful attention (Quaglia et al., 2016), may present a scalable, implementation approach to improving intergroup prosociality. Mindfulness and related meditative practices come in many different forms (e.g., Lippelt et al., 2014). The science of short-term mindfulness has prioritized reducing contemplative practices down to their component parts for isolating and making a mindful quality of attention salient in its practitioners (Heppner & Shirk, 2018). One impact of this could be increased modularity of short-term mindfulness interventions that may allow scientists and practitioners to add and remove mindfulness skillfully in contemplative and social change interventions. As such, mindfulness practices may support receptivity to outgroup members’ suffering, allowing intergroup compassion and kindness to grow, and complement current interventions (whether contemplative or not).

Mindfulness: a “Kind” Kind of Attention in Intergroup Contexts

Humans are apt to “tidy up” their mental lives by prioritizing processing social information with efficiency over accuracy (e.g., Terrizzi & Shook, 2020). People often automatically cognitively discriminate between those who belong to their social groups (“us”) and those who do not (“them”) and develop emotional attachments to these social ingroups (Brewer, 2001; Tajfel, 1981). Though there are certainly situations in which withholding compassion and care from outgroup members is appropriate or correct (described below), in an increasingly interconnected and interdependent world the consequences of distinguishing between us and them can lead to unnecessary and destructive consequences for society.

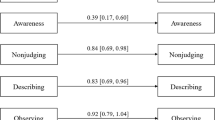

Theories from developmental psychology (Eisenberg, 1988), clinical psychology (Barrett-Lennard, 1981; Rogers, 1975), and social psychological (neuro)science (Batson et al., 1987; Decety & Jackson, 2004) propose that how one directs attention in social interactions (not merely that one is attentive) is critical to the generation of compassion and prosocial behavior. Berry and colleagues (Berry & Brown, 2017; Berry et al., 2020) have suggested that bringing mindfulness into social interactions—whether trained via mindfulness itself or compassion practices that incorporate mindfulness—is an exemplar of an “empathic attentional set” (Barrett-Lennard, 1981) important for generating intergroup prosociality (Batson & Ahmad, 2009). Despite concerns about the ethical neutrality of mindfulness (Monteiro et al., 2015), interventions need not be laden with explicit ethics to promote virtuous outcomes. Mindfulness is skillful in that it conducts its “inner work” unobtrusively. Deploying mindful attention in intergroup interactions can be an act of kindness, whether a kind act is one’s intention or not, as it assuages common intrapsychic hurdles to compassion in intergroup contexts. Figure 1 shows a theoretical framework for mindful attention as a skillful means in intergroup contexts.

Three components involved in the empathic attentional set overlap conceptually with common outgrowths of mindfulness, which are critical in intergroup interactions. First, one must “open [them] self in a deeply responsive way to another person’s feelings” (Barrett-Lennard, 1981, p. 92). In many social contexts, people do not bring much awareness to what they are doing (Killingsworth & Gilbert, 2010). The default mode of processing social information entails speed and efficiency (e.g., Raichle et al., 2001), and people rely on stereotypes to predict interaction partners’ psychological predispositions, social goals, intentions, and behaviors (Rothbart & Taylor, 1992). When in a mindful state, one intentionally receptively focuses on the present and this attentional presence brings clarity to one’s awareness of psychological phenomena (e.g., thoughts, emotions, visceral experiences, Varela & Depraz, 2003). Thus, one may notice habitual, conditioned, and automatized mental processes as they arise and override them (e.g., Papies et al., 2012). This is important for intergroup prosociality as automatized social cognition is central to decisions to withhold compassion and kindness from social outgroup members (see Saucier, 2015 for review).

Second, several theories converge to suggest that before engaging in prosocial acts, humans first take on the “internal frame of reference” of the other person (Rogers, 1959, pp. 210–211). This process—also referred to as mentalizing or perspective taking in social cognitive and affective (neuro)science (Zaki & Mitchell, 2013)—entails adopting or imagining the sensory, motor, visceral, and affective states of others through bottom-up cognitive processes (de Waal, 2008; Decety & Jackson, 2004; Gallese, 2003; Zaki, 2014). Awareness of one’s emotional responses, when confronted with aversive personal events, serves as a starting point for identifying and understanding suffering in others; it allows one to infer or to imagine how similar aversive experiences feel to others (Singer et al., 2009). This presents a serious hurdle to intergroup prosociality, as people are less accurate at identifying emotions across social and cultural lines (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002). A poor or absent understanding of outgroup members’ mental lives may stymie prosocial action or lead to patronizing or ineffective care (e.g., van Leeuwen & Täuber, 2011). Additionally, past research has revealed that it may be more beneficial for an individual to stay within their own perspective in intergroup interactions, suggesting that perspective taking as a strategy for improving intergroup relations should be recommended with caution, as less positive behavior toward outgroup members may be triggered (Vorauer et al., 2009).

Mindfully attending to one’s own inner experiences may prepare one to understand and take on the experiences of outgroup members without the overlay of explicit appeals that may lead these efforts to backfire. Entering a state of mindfulness is most often achieved by focusing attention on and/or openly monitoring one’s own somatic, cognitive, and emotional experiences (Baer, 2009; Lippelt et al., 2014; Hölzel et al., 2011). Individual differences in and training in mindfulness have been shown to correlate with and enhance self-reported awareness of one’s somatic and mental processes (also called interoceptive awareness; Bornemann et al., 2014; Creswell et al., 2007).

Third, when taking the internal frame of reference of the other person, one must do so “with the emotional components and meanings which pertain thereto as if one were the person, but without losing that ‘as if’ condition” (Rogers, 1959, pp. 210–211). Social psychology and social neuroscience have unpacked this tenet of the empathic attentional set to include the important interrelationship between emotion regulation and self-relevant cognition. Specifically, for successful prosocial action, one ought not to become overwhelmed by the emotions of others so that they are unable to discern between their own and others’ suffering. The phenomenological features of this way of attending to others’ pain manifest in feeling concern for others and have been referred to in psychological science as an empathic concern (or compassion) (Batson and Ahmad, 2009; Batson et al., 1987). Empathic concern is contrasted against empathic distress, a self-oriented emotional response to an affected person. Although both these emotions can promote prosocial behavior, empathic concern is more reliable (Batson et al., 1983; Toi & Batson, 1982) and perceived by non-dominant group members as a more genuine motive for helping when expressed by dominant group members (Johnson et al., 2008).

Related to this, there appears to be an advantage of mindfulness and compassion trainings regarding emotion regulation (e.g., Desbordes et al., 2012; see Hölzel et al., 2011 for review). Regulating one’s affective responses that occur when witnessing another person in need is necessary for prosocial action (Batson et al., 2015; Zaki, 2014). Specifically, some physiological arousal in response to others’ suffering may be important for the enactment of prosocial behavior (Decety & Jackson, 2004). One’s subjective experience (i.e., cognitive appraisal) of this physiological arousal in empathic contexts, however, can take on many different forms (e.g., empathic concern, personal distress, moral outrage; Goetz et al., 2010). Intergroup interactions are perceived as threatening and are accompanied by higher physiological arousal (i.e., cardiovascular threat responses) (Mendes et al., 2002), and so may include physiological over-arousal that hinders prosociality. “Being present” with one’s own physiological arousal and accompanying emotional responses may catalyze compassionate responses, rather than personal distress (or attendant emotions less associated with prosociality) (Condon & Feldman Barrett, 2014).

Most important to this emotion regulatory response, contemplative trainings are thought to reduce or partially suspend habitual self-relevant cognition (Brown et al., 2016). Self-relevant cognitions are characteristic of the human default mode of information processing (Killingsworth & Gilbert, 2010), and these cognitions can support the creation and maintenance of conceptual boundaries between self and others that can hinder prosociality (Fennis, 2011). Mindfulness should, and largely does improve clarity of attention directed inward to the self (e.g., Bornemann et al., 2014). When mindful, however, our orientation to the self is altered. Rather than becoming attached to mental phenomena and how they relate to oneself autobiographically (e.g., Metzinger, 2003; Trautwein et al., 2014), a first-person perspective is favored and mental processes (e.g., thoughts, emotions, visceral responses) are seen as transient (Brown & Cordon, 2009; Olendzki, 2005). Relevant to intergroup relations, mindfulness may allow one to interrupt or override the social categorization process as it arises (e.g., Berry & Brown, 2017), as this process is typically marked by ignoring the cognitive complexity of outgroup members and using cognitive shortcuts to assume about their predispositions and intentions to inform social interactions (Park & Judd, 1990). As such, mindful attention may allow empathic concern to grow in social contexts where it is most limited.

In summary, the phenomenological experience of mindfulness, which is encouraged in a variety of contemplative trainings, may present a skillful starting point for overriding common challenges to intergroup prosociality. To support the foregoing theoretical framework, experimental evidence is presented suggesting that mindfulness promotes positive (1) intergroup social cognitive processes and encourage (2) empathy and (3) empathic concern as mechanisms for increasing (4) intergroup prosocial behavior.

Basic Intergroup Social Cognitive Processes

Social Identity

Individuals are motivated to enhance and maintain their self-esteem by perceiving the social groups to which they belong as distinct from and better than outgroups (Tajfel, 1982). Humans develop emotional attachments to their social groups called social identities that “go beyond mere cognitive classification” that divides “us” from “them” (Brewer, 2001, p. 255). Because people derive self-esteem from the relative standing of one’s social ingroup compared to outgroups, even participants randomly assigned to inconsequential groups in the lab are apt to feel more socially connected with the other members of their group and allocate more resources to them (Tajfel, 1978). Though higher prosocial orientations can buffer against harming outgroup members (Aaldering et al., 2018), in zero-sum contexts, privileging one’s group members “de-privileges those who do not belong to it” (Ricard, 2015, p. 277).

Consistent with the thinking that mindfulness reduces self-relevant cognition, Pinazo and Breso (2017) asked whether participants assigned to an 8-week mindfulness training vs. a waitlist control group would show lower deleterious outgrowths of social identification. The mindfulness training in this experiment (study 2) involved cultivating focused and open attention to one’s present experiences, and in later weeks expanded this quality of attention to be deployed in social contexts (i.e., compassion, gratitude, and personal responsibility). Group favoritism was measured by the number of participants from one’s intervention group versus the other one admitted to a room with limited space. Results indicated lower group favoritism after meditation training. Furthermore, participants self-reported lower social distance between themselves and outgroup members. This is important because social categorization and psychological distance are usually preconditions for intergroup neglect and conflict (Mackie et al., 2000; Tajfel, 1982; Tajfel et al., 1971).

Causal Attributions

Attribution is the process by which people make inferences about the causes of one’s own or others’ behaviors and attitudes (Gilbert, 1998; Heider, 1958). In general, people give more weight to others’ stable dispositions instead of situational factors when determining the causes of others’ behavior, an error called the correspondence bias (see Gilbert & Malone, 1995 for review). For example, if a friend fails to return your text message, you might label them as “indifferent” about your friendship or inherently “ill-mannered” and fail to consider that they were dropping off their child at school and forgot to respond to you. In three experiments, Hopthrow et al. (2017) found that participants who completed a brief mindful raisin-eating task, as compared to inactive and closely matched active controls, showed a reduction in the correspondence bias. More germane to this review, attributional biases are often exacerbated in intergroup contexts (e.g., Pettigrew, 1979), and incipient research suggests that the effects of mindfulness practice might allay intergroup attributional biases. An experiment tested whether mindful attention would negate linguistic intergroup bias (Tincher et al., 2015). Participants were randomly assigned to a brief mindfulness training or a control condition involving absorption in personal thoughts. Thereafter, participants were given pictures of a person engaging in harmful or helpful behavior and asked to make a linguistic description (forced multiple choice) about what caused the behavior ranging from concrete to abstract. The researchers found that abiding in a mindful state reduced the tendency to make concrete attributions about outgroup members’ helpful behaviors and abstract attributions about harmful behaviors.

Attitudes

A central concept in social psychology, attitudes are (oftentimes mutable) evaluations of objects that organize cognitive, affective, motivational, and behavioral responses toward those objects (Schwarz & Bohner, 2001). In intergroup interactions, harboring biased attitudes against outgroup members (e.g., prejudice) is associated with lower empathy and helping behavior toward them (e.g., Avenanti et al., 2010; Gaertner et al., 1982), higher pleasant affect at their misfortune (Cikara, 2015; Cikara et al., 2011, 2014), and even full-blown conflict (see Zaki & Cikara, 2015 for review). Much of contemplative science on changing deliberate (explicit) intergroup attitudes has focused on multimodal forms of meditation that integrate compassion and loving-kindness practices alongside mindfulness (Berger et al., 2018; Parks et al., 2014; see Oyler et al., 2021 for review). Though this research is important to establish the benefits of meditation practice, it is difficult to identify the active ingredients in change with such intervention designs. Namely, with multifaceted meditation interventions, it is unclear if the effects are based on mindfulness-based practices, compassion-based practices, or some other non-specific factor. Furthermore, relying on participants’ self-reporting of attitudinal biases is susceptible to deliberate censoring for reasons of social desirability and self-presentation (Schwarz & Bohner, 2001).

Psychological theory suggests that social cognition often operates outside of deliberate awareness (i.e., implicit cognition; Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). Even when people endorse egalitarian attitudes and object to prejudice, implicit attitudinal biases may have downstream consequences for biased intergroup behavior (Devine, 1989). Lueke and Gibson (2015) found that among self-identifying White individuals, brief mindfulness training, relative to a narrative control, predicted lower implicit race bias toward Black individuals. Follow-up analyses indicated that mindfulness reduced implicit bias because of attenuated automatic activation of conditioned Black/bad associations. Thus, mindful attention may interrupt the activation of implicit associations altogether, removing the need to override these responses.

Empathy

Empathy includes a family of processes that entail adopting the mental states of others. Though cognitive/affective manifestations of empathy are associated with prosocial behaviors (see Weisz & Cikara, 2020), these forms of empathy are not always reliable in skillful moral decision-making (Bloom, 2017; Decety, 2021) and intergroup interactions (Stürmer et al., 2006). What is more, mindfulness does not always enhance all forms of empathy (e.g., Berry & Brown, 2017; Lim et al., 2015; Ridderinkhof et al., 2017; Winning & Boag, 2015). As previously mentioned, it may be more beneficial for an individual to stay within their own perspective in intergroup interaction situations (Vorauer et al., 2009).

Edwards et al. (2017) conducted a factorial design experiment that brings clarity to the role of mindfulness and empathy in intergroup prosociality. Young adult participants either were assigned to actively take the perspective of an older adult or were assigned to a control condition. The hypothesis was that perspective taking would counterintuitively increase implicit age bias, because people often “coordinate” their own perspective with stereotypical understandings of outgroup members. Participants were also assigned to either a mindfulness condition or a control condition. Consistent with their hypothesis, mindfulness buffered the effects of perspective taking on negative implicit age bias, presumably because mindfulness allowed one to “flexibly connect” with their own perspective with less influence from stereotypes. Consistent with our theoretical framework, this study supports the contention that mindfully focusing attention on oneself may create an optimal starting point for intergroup compassion.

Empathic Concern

When confronted with another person’s suffering, people may adopt a self- or other-oriented motivational/emotional focus. Personal distress is a self-oriented emotion that can lead to emotional withdrawal or escape from a person’s predicament or lead them to help to reduce their own negative affect (e.g., Batson et al., 1987). Empathic concern (also called compassion) is an other-oriented emotional response to others’ suffering, and concerns motivation and often an act to reduce their suffering (e.g., Batson et al., 2015; Decety, 2021). In three recent experiments, Berry et al. (2018) found that mindfulness trainees, relative to attention-based, relaxation, and inactive controls, wrote more comforting emails to ostracized strangers and then included them more in an online game. Empathic concern mediated the effect of mindfulness training on helping behavior (Berry et al., 2018). Furthermore, in these studies, the target of mindfulness trainees’ empathic concern and helping behavior was a stranger. Lack of familiarity with an affected person is a common cognitive division between self and others that reduces prosociality (e.g., Stinson & Ickes, 1992).

Because mindfulness may attenuate self-relevant cognition, it may be particularly effective in enhancing empathic concern in intergroup relations. Evidence from two experiments has found that brief mindfulness trainees, compared to attention-based control trainees, feel more empathic concern (but not personal distress) for racial outgroup members in social pain (Berry et al., 2021a). Future work will do well to experimentally manipulate the race of the empathy target, as strong inferences cannot be drawn from this study about mindfulness training effects in intergroup relations. Although there are limitations to this study design, it is noteworthy that participants were self-identifying White individuals—members of an empowered majority group. Thus, it could be inferred that brief mindfulness training promotes compassion and helping in an intergroup context.

Intergroup Prosocial Behaviors

Intergroup Contact Intentions

Health and social psychological perspectives on behavior change indicate that one’s commitment to or intention to engage in a behavior is a precursor to engaging in that behavior (e.g., Theory of Reasoned Action/Theory of Planned Behavior; e.g., Fishbein & Ajzen, 1977). Two studies have found that multidimensional meditation practices increase readiness for intergroup contact (Berger et al., 2018) and result in greater contact intention (Parks et al., 2014).

(Costly) Monetary-Related Prosocial Behavior

Helping can be financially costly (Cameron et al., 2019), and people are motivated to avoid these costs (see Zaki, 2014 for review). Mindfulness may be well suited for overcoming these motivational challenges. One experiment found that brief instruction in a focused attention form of mindfulness practice, relative to active and inactive controls, predicted lower discrimination in how much participants entrusted same race and other race interaction partners with their money (Lueke & Gibson, 2016). In another experiment, Frost (2017) found that a focused attention mindfulness meditation, relative to a waitlist control, reduced parochial giving in a public goods game. Interestingly, monetary helping seems to be mutable to mindfulness only in more motivationally challenging contexts; contrary to the findings presented here, Berry et al. (2020) found effect sizes comparing mindfulness training to various controls on monetary-related prosocial behavior largely clustered around zero in social contexts in which the social identity of the help recipient was unknown.

Aversive Racism and Helping Behavior

Explicitly endorsing racism and negative intergroup attitudes is aversive to dominant group members (called Aversive Racism, Dovidio & Gaertner, 2000). But because people still harbor racist attitudes, they rationalize the presence of situational features (e.g., bystanders, task complexity, task duration, and/or danger) as reasons for not helping outgroup members (e.g., Kunstman & Plant, 2008). These rationalizations exacerbate the gap in preferentially helping ingroup members over outgroup members (Saucier et al., 2005). In a recent experiment by Berry et al. (2021b), female graduate students and community adult participants were randomized to receive four days of focused (mindful) attention training or a structurally equivalent sham meditation training (cf., Zeidan et al., 2015). Interestingly, mindfulness trainees were more helpful to racial outgroup members in the “crutches simulation” used by Condon et al. (2013) and Lim et al. (2015). Furthermore, these effects generalized outside of constrained lab contexts, as mindfulness trainees who were initially lower in trait mindfulness reported helping racial ingroup and outgroup members more frequently in a daily diary measure.

Challenges and Future Considerations

As a receptive, psychological state that can be trained (e.g., Quaglia et al., 2016) and situationally manipulated (Heppner & Shirk, 2018), this literature review suggests that mindfulness dampens intrapsychic boundaries to intergroup prosociality, including social categorization (Pinazo & Breso, 2017), biased causal attributions (Tincher et al., 2015), and implicit intergroup attitudes (Lueke & Gibson, 2016). What is more, even short-term training in focused attention forms of mindfulness create a flexible frame of reference to take the perspective of outgroup members (e.g., Edwards et al., 2017). These trainings also promote higher empathic concern (Berry et al., 2021a), intentions for intergroup contact (Berger et al., 2018; Parks et al., 2014), and prosocial behaviors toward social outgroup members (Berry et al., 2021a, b; Frost, 2017; Lueke & Gibson, 2016). Despite the promise of this foregoing research, there are many questions left to test if mindfulness is indeed a skillful starting point for intergroup prosociality that complements existing efforts.

Dispositional Moderators

Like most interventions, mindfulness practices are not uniformly beneficial for everyone. The benefits of mindfulness training for empathic understanding (Ridderinkhof et al., 2017) and prosocial behavior appear to be partially dependent on individual differences in social goals and prosocial orientations (see Condon, 2019; Poulin et al., 2021 for reviews). Though the research on dispositional moderators of mindfulness training in intergroup contexts has yet to begin, future research might focus on whether mindfulness can reduce the influence of defensive intergroup attitudes such as racism and social dominance orientation on intergroup prosociality (e.g., Pratto et al., 1994).

Parochial Prosociality

Humans are a prosocial species (e.g., Brown et al., 2012), but we often reserve prosociality for known or socially close others (Kurzban et al., 2015) Specifically, people show higher prosociality toward social ingroup members than outgroup members, referred to as the “empathy gap” or parochial empathy (e.g., Cikara et al., 2014). Over and above empathy itself, parochial empathy predicts lower altruism and higher harm toward social outgroup members (Bruneau et al., 2015, 2017). Thus, it is the empathy gap, rather than a mere lack of empathy itself, that portends challenging intergroup relationships.

Various mindfulness trainings have been found to close this empathy gap in prosocial behaviors elicited by laboratory-based tasks and simulations (Berry et al., 2021a; Frost, 2017; Lueke & Gibson, 2016). Yet in a study with real-world measures captured by daily diary methods, both four-day mindfulness trainees and sham mindfulness trainees showed parochial helping behaviors toward racial ingroup members (Berry et al., 2021b). Social groups are often socially and physically insulated from each other, limiting opportunities for meaningful intergroup contact (see Piff et al., 2018 for review). This finding is inconsistent with our theoretical framework but could have a variety of explanations. For example, four days of training in mindfulness may not be potent enough to reduce parochial prosociality. Researchers should consider the appropriateness of mindfulness practices in bridging the empathy gap in real-world contexts. It is noteworthy that multidimensional meditation practices can increase intergroup contact intentions (Berger et al., 2018; Parks et al., 2014). Identifying the active ingredients in these contemplative trainings may provide insight about whether and how mindfulness compliments interventions that reduce parochial contact—for instance, mental simulation of a future helping episode (i.e., episodic simulation; Gaesser et al., 2020).

Intergroup Antipathy

Valuing the affected person’s welfare is a necessary precondition to feeling compassion for them and enacting prosocial behavior (e.g., Batson et al., 2007). Intergroup relations are embedded within historical and cultural contexts including intergroup moral violations (e.g., slavery, colonialism). Explicit appeals to empathize with outgroup members, as exemplified by perspective taking or other compassion-enhancing forms of conflict resolution, are effective only insofar as one is receptive to the person and their predicament. Thus, efforts to reduce conflict by directly increasing compassion may be difficult to implement when there is pre-existing antipathy toward the outgroup (Galinsky et al., 2005), such as when holding racially prejudiced attitudes (Avenanti et al., 2010), intergroup competition over limited resources (Cikara et al., 2014), or intractable conflicts (see Klimecki, 2019 for review).

Mindfulness practices reduce hostile and retaliatory attitudes and actions. Several studies have found that short-term training in mindfulness can reduce retaliatory responses to social rejection (Heppner et al., 2008) and provocation from a stranger (DeSteno et al., 2018) or supervisor (Liang et al., 2018). In an experiment by Kirk et al. (2016), participants were randomized to receive an eight-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction course (Kabat-Zinn, 1990) or a structurally equivalent health intervention. After training, participants played the Ultimatum Game in which an ostensible other participant offered a portion of their money ($20 total) to the participant. The participant either accepted or declined the offer and declining meant that neither party would receive any money. Mindfulness trainees relative to controls were more likely to accept very unfair offers (between $1 and $3 out of $20).

The place of mindfulness training in ameliorating intergroup conflict marked by antipathy is yet to be tested. Although mindfulness may dampen existing hostilities and open individuals to the humanity of outgroup members, anger and outrage at moral violations are important emotional responses to inequity that can motivate restorative justice (van Doorn et al., 2014). Conflict resolution interventions that promote liking and harmony between groups can backfire and delegitimize the needs of disempowered groups (Dixon et al., 2010). So, mindfulness may produce similar unwanted consequences. On the contrary, an experiment by Berry et al., (2018; study 3) found that brief mindfulness training compared to an active and inactive control did not affect anger felt toward perpetrators of social exclusion. Instead, participants’ emotional focus was that of concern for the victim which led to socially restorative behaviors (i.e., inclusion and comforting).

Is Intergroup Compassion Always Virtuous?

Group membership is necessary to human survival (Brewer & Caporael, 2006), as it allows for reciprocal exchange of tangible resources that fulfill basic physiological needs (De Dreu et al., 2014) and psychological resources that fulfill the psychological need to belong (e.g., Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Just as resources are shared with members of the ingroup, it may also be an adaptive advantage to engage in competition with the outgroup via defensive attitudes, neglect, withholding care and kindness, and even aggression (Cikara et al., 2011; Tooby & Cosmides, 2010). Thus, intergroup prosociality is not always appropriate or correct. For example, it would be counterproductive to indiscriminately behave prosocially toward an outgroup who had committed acts of violence against one’s ingroup. Future research should test if mindfulness practice would encourage these distinctions in these more challenging contexts.

Concern About Social Consequences of Intergroup Bias

Deficits in intergroup prosociality may persist because people lack explicit awareness of the racial biases (Devine, 1989; Dovidio & Gaertner, 2000; Wilson & Brekke, 1994). Theory on prejudice reduction has suggested that becoming aware of biases is not enough to reduce them, and one must also be aware of and motivated to avoid the social consequences of their biases (Plant & Devine, 2009). Including mindful attention alongside interventions that bring awareness to the consequences of bias (e.g., stereotype replacement and counter-stereotypic imaging (Devine et al., 2012) could show potential in reducing defensive responses to learning that one is biased.

Social Class and Power Asymmetries: Intergroup Harmony is a Two-Way Street

Power asymmetries are defined by social class systems in which one group has more power or subjective and/or objective social status than the other (Piff et al., 2018). Moreover, power asymmetries are a common feature of intergroup contexts that constrain intergroup prosocial action (see Zaki & Cikara, 2015 for review). A mounting problem in the United States and other countries, power asymmetry in income inequality, for example, which limits access to education, public services, objective wealth, careers, and attendant indices of asymmetry in social status and power (Piff & Robinson, 2017), has been growing over the last century (Piketty & Saez, 2003). People in power will “dig in their heels” to maintain it (Pratto et al., 1994; Sidanius et al., 2001), and the costs are lower empathy (Hudson et al., 2019) and less redistribution of resources for those less fortunate (Brown-Iannuzzi et al., 2015).

Perhaps one of the greatest challenges in power asymmetries is that the upper class holds more economic and social resources, and paradoxically are proportionally less willing to redistribute these resources (Kraus et al., 2012; Piff et al., 2010). Currently, there is no experimental evidence that mindfulness reduces motivation to hold onto power. Correlational research, however, indicates that undergraduates and working adults higher in the disposition to deploy mindful attention in everyday life had smaller financial desire discrepancies (Brown et al., 2009) controlling for current financial status. That is, they had less of a gap between their current financial situation and what they desired in the future. Future research should examine if practicing mindfulness will attenuate the desire to maintain power.

To date, contemplative science has largely focused on the effects of mindfulness and other meditation practices for dominant group members in promoting intergroup prosociality. Failing to study non-dominant group members’ responses to mindfulness-induced changes in dominant group members’ attitudes and behaviors presents a serious gap in our understanding. While people may show kindness to outgroup members because they feel empathy and concern for them (Johnson et al., 2008; Stürmer et al., 2006), prosocial responses might be motivated by dominant group members’ wanting to appear unprejudiced (Richeson & Shelton, 2003) or to establish dominance over outgroup members (Schneider et al., 1996). Likewise, non-dominant group members may hold resentment toward dominant group members (Shnabel & Nadler, 2008) and may not trust that dominant group members are well-intentioned (Kunstman et al., 2016), or may fear rejection by dominant group members (Shelton & Richeson, 2005).

Researchers should consider incorporating mindfulness into intergroup dyads for three reasons. One, a growing number of studies have found that dominant group members provide more kindness and care toward outgroup members after receiving a mindfulness intervention. Two, research assumes that intergroup prosociality shown by dominant group members in studies of mindfulness are skillful. Including the voice of non-dominant group members in our science can inform us about whether intergroup prosociality is wanted, genuine, and effective at promoting mutually beneficial outcomes for non-dominant group members (e.g., cooperation). Three, there are interactive benefits in intergroup dyads that may be amplified by mindfulness. Positive intergroup attitudes in power asymmetric dyads are increased when low-power groups (e.g., Mexican immigrants) give their perspective and communicate about the challenges they face and high-power groups (e.g., White Americans) listen and summarize these challenges (Bruneau & Saxe, 2012). Mindfulness might intensify these effects by increasing other-oriented social cognition among dominant group members and reducing defensiveness among non-dominant group members.

Over the past two decades, research on mindfulness and its positive outgrowths has exponentiated (Brown et al., 2015). Mindfulness is a multibillion-dollar industry (Poulin et al., 2021), with growing public, corporate, and political interest in its practice (Ryan, 2012; Van Dam et al., 2018). Scientists have begun testing the efficacy of affordable mindfulness-based smartphone applications for interpersonal well-being (e.g., DeSteno et al., 2018; Lim et al., 2015). Recent research has uncovered the psychological benefits of mindfulness interventions for intergroup relations. While this work is important, research on integrating mindfulness into intergroup interventions should skillfully consider boundary conditions, adverse effects, and questions that challenge the notion that mindfulness benefits intergroup relations.

References

Aaldering, H., Ten Velden, F. S., van Kleef, G. A., & De Dreu, C. K. (2018). Parochial cooperation in nested intergroup dilemmas is reduced when it harms out-groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114(6), 909–923. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000125

Avenanti, A., Sirigu, A., & Aglioti, S. M. (2010). Racial bias reduces empathic sensorimotor resonance with other-race pain. Current Biology, 20(11), 1018–1022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.071

Baer, R. A. (2009). Self-focused attention and mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based treatment. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 38(S1), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070902980703

Barrett-Lennard, G. T. (1981). The empathy cycle: Refinement of a nuclear concept. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 28(2), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.28.2.91

Batson, C. D., & Ahmad, N. Y. (2009). Using empathy to improve intergroup attitudes and relations. Social Issues and Policy Review, 3(1), 141–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2409.2009.01013.x

Batson, C. D., O’Quinn, K., Fultz, J., Vanderplas, M., & Isen, A. (1983). Influence of self-report distress and empathy on egoistic versus altruistic motivation to help. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(3), 706–718. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.3.706

Batson, C. D., Fultz, J., & Schoenrade, P. A. (1987). Distress and empathy: Two qualitatively distinct vicarious emotions with different motivational consequences. Journal of Personality, 55(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1987.tb00426.x

Batson, C. D., Eklund, J. H., Chermok, V. L., Hoyt, J. L., & Ortiz, B. G. (2007). An additional antecedent of empathic concern: Valuing the welfare of the person in need. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.65

Batson, C. D., Lishner, D. A., & Stocks, E. L. (2015). The empathy–altruism hypothesis. In D. A. Shroeder & W. G. Graziano (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of prosocial behavior (pp. 259–281). Oxford University Press.

Baumeister, R., & Leary, M. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Berger, R., Brenick, A., & Tarrasch, R. (2018). Reducing Israeli-Jewish pupils’ outgroup prejudice with a mindfulness and compassion-based social-emotional program. Mindfulness, 9(6), 1768–1779.

Berry, D. R., & Brown, K. W. (2017). Reducing separateness with presence: How mindfulness catalyzes intergroup prosociality. In J. Karremans & E. Papies (Eds.), Mindfulness in social psychology (pp. 153–166). Psychology Press.

Berry, D. R., Cairo, A. H., Goodman, R. J., Quaglia, J. T., Green, J. D., & Brown, K. W. (2018). Mindfulness increases empathic and prosocial responses toward ostracized strangers through empathic concern. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(1), 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000392

Berry, D. R., Hoerr, J. P., Cesko, S., Alayoubi, A., Carpio, K., Zirzow, H., Walters, W., Scram, G., Rodriguez, K., & Beaver, V. (2020). Does mindfulness training without explicit ethics-based instruction promote prosocial behaviors? A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(8), 1247–1269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219900418

Berry, D. R., Wall, C., Cairo, A., Plonski, P. E., & Brown, K. W. (2021a). Brief mindfulness instruction increases prosocial helping of an ostracized racial outgroup member. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/n2xzp

Berry, D. R., Wall, C. S., Tubbs, J. D., Zeidan, F., & Brown, K. W. (2021b). Short-term training in mindfulness predicts helping behavior toward racial ingroup and outgroup members. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 19485506211053095. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506211053095

Bloom, P. (2017). Against empathy: The case for rational compassion. Random House.

Bodhi, B. (2011). What does mindfulness really mean? A Canonical Perspective. Contemporary Buddhism, 12(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/14639947.2011.564813

Bornemann, B., Herbert, B. M., Mehling, W. E., & Singer, T. (2014). Differential changes in self-reported aspects of interoceptive awareness through 3 months of contemplative training. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1504. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01504

Brewer, M. B. (2001). Ingroup identification and intergroup conflict. In R. D. Ashmore, L. Jussim, & D. Wilder (Eds.), Social identity, intergroup conflict, and conflict reduction (pp. 17–41). Oxford University Press.

Brewer, M. B., & Caporael, L. R. (2006). An evolutionary perspective on social identity: Revisiting groups. In M. Schaller, J. A. Simpson, & D. T. Kenrick (Eds.), Evolution and social psychology (pp. 143–161). Psychology Press.

Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 211–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/10478400701598298

Brown, K. W., Kasser, T., Ryan, R. M., Linley, P. A., & Orzech, K. (2009). When what one has is enough: Mindfulness, financial desire discrepancy, and subjective well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(5), 727–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.07.002

Brown, S. L., Brown, R. M., & Preston, S. (2012). The human caregiving system: A neuroscience model of compassionate motivation and behavior. In S. Brown, R. Brown, & L. Penner (Eds.), Moving beyond self-interest: Perspectives from evolutionary biology, neuroscience, and the social sciences (pp. 75–88). Oxford University Press.

Brown, K. W., Creswell, J. D., & Ryan, R. M. (2015). Handbook of mindfulness: Theory, research, and practice. Guilford Press.

Brown, K. W., Berry, D. R., & Quaglia, J. T. (2016). The hypo-egoic expression of mindfulness in social life. In K. W. Brown & M. R. Leary (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of hypo-egoic phenomena (pp. 147–159). Oxford University Press.

Brown, K. W., & Cordon, S. (2009). Toward a phenomenology of mindfulness: Subjective experience and emotional correlates. In Didonna, F. (Ed.), Clinical handbook of mindfulness (pp. 59–81). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-09593-6_5

Brown-Iannuzzi, J. L., Lundberg, K. B., Kay, A. C., & Payne, B. K. (2015). Subjective status shapes political preferences. Psychological Science, 26(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614553947

Bruneau, E. G., & Saxe, R. (2012). The power of being heard: The benefits of ‘perspective-giving’ in the context of intergroup conflict. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(4), 855–866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.02.017

Bruneau, E. G., Cikara, M., & Saxe, R. (2015). Minding the gap: Narrative descriptions about mental states attenuate parochial empathy. PLoS ONE, 10(10), e0140838. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140838

Bruneau, E. G., Cikara, M., & Saxe, R. (2017). Parochial empathy predicts reduced altruism and the endorsement of passive harm. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(8), 934–942. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617693064

Cameron, C. D., Hutcherson, C. A., Ferguson, A. M., Scheffer, J. A., Hadjiandreou, E., & Inzlicht, M. (2019). Empathy is hard work: People choose to avoid empathy because of its cognitive costs. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148(6), 962–976. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000595

Chang, D. F., Donald, J., Whitney, J., Miao, I. Y., & Sahdra, B. K. (2022). Does mindfulness improve intergroup bias, internalized bias, and anti-bias outcomes? A meta-analysis of the evidence and agenda for future research. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/5wev3

Cikara, M. (2015). Intergroup schadenfreude: Motivating participation in collective violence. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 3, 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2014.12.007

Cikara, M., Bruneau, E. G., & Saxe, R. R. (2011). Us and them: Intergroup failures of empathy. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(3), 149–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411408713

Cikara, M., Bruneau, E., Van Bavel, J. J., & Saxe, R. (2014). Their pain gives us pleasure: How intergroup dynamics shape empathic failures and counter-empathic responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 55, 110–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.06.007

Condon, P. (2019). Meditation in context: Factors that facilitate prosocial behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.09.011

Condon, P., & Feldman Barrett, L. (2014). Conceptualizing and experiencing compassion. Emotion, 13(5), 817–821. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033747

Condon, P., & Makransky, J. (2020). Recovering the relational starting point of compassion training: A foundation for sustainable and inclusive care. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(6), 1346–1362. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620922200

Condon, P., Desbordes, G., Miller, W., & DeSteno, D. (2013). Meditation increases compassionate responses to suffering. Psychological Science, 24(10), 2125–2127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613485603

Creswell, J. D., Way, B. M., Eisenberger, N. I., & Lieberman, M. D. (2007). Neural correlates of dispositional mindfulness during affect labeling. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69(6), 560–565. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180f6171f

De Dreu, C. K., Balliet, D., & Halevy, N. (2014). Parochial cooperation in humans: Forms and functions of self-sacrifice in intergroup conflict. Advances in Motivation Science, 1, 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.adms.2014.08.001

de Waal, F. B. (2008). Putting the altruism back into altruism: The evolution of empathy. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 279–300. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093625

Decety, J. (2021). Why empathy is not a reliable source of information in moral decision making. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(5), 425–430.

Decety, J., & Jackson, P. L. (2004). The functional architecture of human empathy. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews, 3(2), 71–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534582304267187

Depow, G. J., Francis, Z., & Inzlicht, M. (2021). The experience of empathy in everyday life. Psychological Science, 32(8), 1198–1213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797621995202

Desbordes, G., Negi, L. T., Pace, T. W., Wallace, B. A., Raison, C. L., & Schwartz, E. L. (2012). Effects of mindful-attention and compassion meditation training on amygdala response to emotional stimuli in an ordinary, non-meditative state. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 292. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00292

DeSteno, D., Lim, D., Duong, F., & Condon, P. (2018). Meditation inhibits aggressive responses to provocations. Mindfulness, 9, 1117–1122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0847-2

Devine, P. G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.1.5

Devine, P. G., Forscher, P. S., Austin, A. J., & Cox, W. T. (2012). Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(6), 1267–1278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.06.003

Dixon, J., Tropp, L. R., Durrheim, K., & Tredoux, C. (2010). “Let them eat harmony”: Prejudice-reduction strategies and attitudes of historically disadvantaged groups. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(2), 76–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721410363366

Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. (2000). Aversive racism and selection decisions: 1989 and 1999. Psychological Science, 11(4), 315–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00262

Edwards, D. J., McEnteggart, C., Barnes-Holmes, Y., Lowe, R., Evans, N., & Vilardaga, R. (2017). The impact of mindfulness and perspective-taking on implicit associations toward the elderly: A relational frame theory account. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1615–1622.

Eisenberg, N. (1988). The development of prosocial and aggressive behavior. In M. H. Bornstein & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Developmental psychology: An advanced textbook (pp. 461–495). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Elfenbein, H. A., & Ambady, N. (2002). On the universality and cultural specificity of emotion recognition: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 128(2), 203–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.203

Fennis, B. M. (2011). Can’t get over me: Ego depletion attenuates prosocial effects of perspective taking. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41(5), 580–585. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.828

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1977). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 10(2), 177–188.

Frost, K. (2017). Calming meditation increases altruism, decreases parochialism. bioRxiv. 060616. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2017/04/10/060616.full.pdf

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., & Johnson, G. (1982). Race of victim, nonresponsive bystanders, and helping behavior. The Journal of Social Psychology, 117(1), 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1982.9713409

Gaesser, B., Shimura, Y., & Cikara, M. (2020). Episodic simulation reduces intergroup bias in prosocial intentions and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(4), 683–705. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000194

Galinsky, A. D., Ku, G., & Wang, C. S. (2005). Perspective-taking and self-other overlap: Fostering social bonds and facilitating social coordination. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 8(2), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430205051060

Gallese, V. (2003). The roots of empathy: The shared manifold hypothesis and the neural basis of intersubjectivity. Psychopathology, 36(4), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1159/000072786

Gilbert, D. T. (1998). Ordinary personology. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 89–150). McGraw-Hill.

Gilbert, D. T., & Malone, P. S. (1995). The correspondence bias. Psychological Bulletin, 117(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.21

Goetz, J. L., Keltner, D., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 351–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018807

Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review, 102(1), 4.

Heider, F. (1958). The naive analysis of action. In F. Heider (Ed.), The psychology of interpersonal relations (pp. 79–124). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Heppner, W. L., & Shirk, S. D. (2018). Mindful moments: A review of brief, low-intensity mindfulness meditation and induced mindful states. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 12(12), e12424. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12424

Heppner, W. L., Kernis, M. H., Lakey, C. E., Campbell, W. K., Goldman, B. M., Davis, P. J., & Cascio, E. V. (2008). Mindfulness as a means of reducing aggressive behavior: Dispositional and situational evidence. Aggressive Behavior, 34(5), 486–496. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20258

Hölzel, B. K., Lazar, S. W., Gard, T., Schuman-Olivier, Z., Vago, D. R., & Ott, U. (2011). How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 537–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611419671

Hopthrow, T., Hooper, N., Mahmood, L., Meier, B. P., & Weger, U. (2017). Mindfulness reduces the correspondence bias. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 70(3), 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2016.1149498

Hudson, S. K. T. J., Cikara, M., & Sidanius, J. (2019). Preference for hierarchy is associated with reduced empathy and increased counter-empathy towards others, especially out-group targets. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 85, 103871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2019.103871

Johnson, J. D., Bushman, B. J., & Dovidio, J. F. (2008). Support for harmful treatment and reduction of empathy toward blacks: “Remnants” of stereotype activation involving Hurricane Katrina and “Lil’ Kim”. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(6), 1506–1513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2008.07.002

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. Delacorte.

Kang, Y., Gray, J. R., & Dovidio, J. F. (2014). The nondiscriminating heart: Lovingkindness meditation training decreases implicit intergroup bias. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(3), 1306–1313. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034150

Karremans, J., & Papies, E. (2017). Mindfulness in social psychology. Psychology Press.

Killingsworth, M. A., & Gilbert, D. T. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science, 330(6006), 932–932. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1192439

Kirk, U., Gu, X., Sharp, C., Hula, A., Fonagy, P., & Montague, P. R. (2016). Mindfulness training increases cooperative decision making in economic exchanges: Evidence from fMRI. NeuroImage, 138, 274–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.05.075

Klimecki, O. M. (2019). The role of empathy and compassion in conflict resolution. Emotion Review, 11(4), 310–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073919838609

Kraus, M. W., Piff, P. K., Mendoza-Denton, R., Rheinschmidt, M. L., & Keltner, D. (2012). Social class, solipsism, and contextualism: How the rich are different from the poor. Psychological Review, 119(3), 546–572. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028756

Kunstman, J. W., & Plant, E. A. (2008). Racing to help: Racial bias in high emergency helping situations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(6), 1499–1510. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012822

Kunstman, J. W., Tuscherer, T., Trawalter, S., & Lloyd, E. P. (2016). What lies beneath? Minority group members’ suspicion of Whites’ egalitarian motivation predicts responses to Whites’ smiles. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(9), 1193–1205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216652860

Kurzban, R., Burton-Chellew, M. N., & West, S. A. (2015). The evolution of altruism in humans. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 575–599. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015355

Latané, B., & Darley, J. M., & (1970). The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn't he help? Appleton Century Crofts.

Leiberg, S., Klimecki, O., & Singer, T. (2011). Short-term compassion training increases prosocial behavior in a newly developed prosocial game. PLoS ONE, 6(3), e17798. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017798

Liang, L. H., Brown, D. J., Ferris, D. L., Hanig, S., Lian, H., & Keeping, L. M. (2018). The dimensions and mechanisms of mindfulness in regulating aggressive behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(3), 281–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000283

Lim, D., Condon, P., & DeSteno, D. (2015). Mindfulness and compassion: An examination of mechanism and scalability. PLoS ONE, 10(2), e0118221. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118221

Lippelt, D. P., Hommel, B., & Colzato, L. S. (2014). Focused attention, open monitoring and loving kindness meditation: Effects on attention, conflict monitoring, and creativity–A review. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1083. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01083

Lueke, A., & Gibson, B. (2015). Mindfulness meditation reduces implicit age and race bias: The role of reduced automaticity of responding. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(3), 284–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550614559651

Lueke, A., & Gibson, B. (2016). Brief mindfulness meditation reduces discrimination. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 3(1), 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/cns0000081

Mackie, D. M., Devos, T., & Smith, E. R. (2000). Intergroup emotions: Explaining offensive action tendencies in an intergroup context. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(4), 602–616.

Mendes, W., Blascovich, J., Lickel, B., & Hunter, S. (2002). Challenge and threat during social interactions with White and Black men. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(7), 939–952. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616720202800707

Metzinger, T. (2003). Phenomenal transparency and cognitive self-reference. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 2(4), 353–393. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:PHEN.0000007366.42918.eb

Monteiro, L. M., Musten, R. F., & Compson, J. (2015). Traditional and contemporary mindfulness: Finding the middle path in the tangle of concerns. Mindfulness, 6, 1–13.

Olendzki, A. (2005). The roots of mindfulness. In C. K. Germer, R. D. Siegel, & P. R. Fulton (Eds.), Mindfulness and psychotherapy (pp. 241–261). Guilford.

Oyler, D. L., Price-Blackshear, M. A., Pratscher, S. D., & Bettencourt, B. A. (2021). Mindfulness and intergroup bias: A systematic review. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 1368430220978694. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220978694

Papies, E. K., Barsalou, L. W., & Custers, R. (2012). Mindful attention prevents mindless impulses. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(3), 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611419031

Park, B., & Judd, C. M. (1990). Measures and models of perceived group variability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(2), 173–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.2.173

Parks, S., Birtel, M. D., & Crisp, R. J. (2014). Evidence that a brief meditation exercise can reduce prejudice toward homeless people. Social Psychology, 45(6), 458–465. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000212

Penner, L. A., Fritzsche, B. A., Craiger, J. P., & Freifeld, T. R. (1995). Measuring the prosocial personality. In J. N. Butcher & C. D. Spielberger (Eds.), Advances in personality assessment (pp. 147–163). Psychology Press.

Pettigrew, T. F. (1979). The ultimate attribution error: Extending Allport’s cognitive analysis of prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 5(4), 461–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616727900500407

Piff, P. K., & Robinson, A. R. (2017). Social class and prosocial behavior: Current evidence, caveats, and questions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 18, 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.06.003

Piff, P. K., Kraus, M. W., Côté, S., Cheng, B. H., & Keltner, D. (2010). Having less, giving more: The influence of social class on prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(5), 771–784. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020092

Piff, P. K., Kraus, M. W., & Keltner, D. (2018). Unpacking the inequality paradox: The psychological roots of inequality and social class. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 57, 53–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2017.10.002

Piketty, T., & Saez, E. (2003). Income inequality in the United States, 1913–1998. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1162/00335530360535135

Pinazo, D., & Breso, E. (2017). The effects of a self-observation-based meditation intervention on acceptance or rejection of the other. International Journal of Psychology, 52(4), 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12223

Plant, E. A., & Devine, P. G. (2009). The active control of prejudice: Unpacking the intentions guiding control efforts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(3), 640–652. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012960

Poulin, M., Ministero, L., Gabriel, S., Morrison, C., Naidu, E., & Poulin, M. J. (2021). Minding your own business? Mindfulness decreases prosocial behavior for those with independent self-construals. Psychological Science, 32(11), 1699–1708. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976211015184

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(4), 741–763. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.741

Quaglia, J. T., Braun, S. E., Freeman, S. P., McDaniel, M. A., & Brown, K. W. (2016). Meta-analytic evidence for effects of mindfulness training on dimensions of self-reported dispositional mindfulness. Psychological Assessment, 28(7), 803–818. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000268

Quaglia, J. T. (2022). One compassion, many means: A big two analysis of compassionate behavior. Mindfulness, 1–13.

Raichle, M. E., MacLeod, A. M., Snyder, A. Z., Powers, W. J., Gusnard, D. A., & Shulman, G. L. (2001). A default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(2), 676–682. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.98.2.676

Ricard, M. (2015). Altruism: The power of compassion to change yourself and the world. Atlantic Books Ltd.

Richeson, J. A., & Shelton, J. N. (2003). When prejudice does not pay: Effects of interracial contact on executive function. Psychological Science, 14(3), 287–290.

Ridderinkhof, A., de Bruin, E. I., Brummelman, E., & Bögels, S. M. (2017). Does mindfulness meditation increase empathy? An Experiment. Self and Identity, 16(3), 251–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2016.1269667

Rogers, C. R. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality, and interpersonal relationships, as developed in the client-centered framework. In S. Koch (Ed.), Psychology: A study of a science (Vol. 3, pp. 184–256). McGraw-Hill.

Rogers, C. R. (1975). Empathic: An unappreciated way of being. The Counseling Psychologist, 5, 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/001100007500500202

Rothbart, M., & Taylor, M. (1992). Category labels and social reality: Do we view social categories as natural kinds? In G. R. Semin & K. Fiedler (Eds.), Language, interaction and social cognition (pp. 11–36). Sage Publications Inc.

Ryan, T. (2012). A mindful nation: How a simple practice can help us reduce stress, improve performance, and recapture the American spirit. Hay House

Saguy, T., Tausch, N., Dovidio, J. F., & Pratto, F. (2009). The irony of harmony: Intergroup contact can produce false expectations for equality. Psychological Science, 20(1), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02261.x

Saucier, D. A., Miller, C. T., & Doucet, N. (2005). Differences in helping Whites and Blacks: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0901_1

Saucier, D. A. (2015). Race and prosocial behavior. In D. A. Schroeder & W. G. Graziano (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of prosocial behavior (pp. 392–414). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399813.013.019

Schneider, M. E., Major, B., Luhtanen, R., & Crocker, J. (1996). Social stigma and the potential costs of assumptive help. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(2), 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296222009

Schwarz, N., & Bohner, G. (2001). The construction of attitudes. In A. Tesser & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Intraindividual processes (pp. 436–457). Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Shelton, J. N., & Richeson, J. A. (2005). Intergroup contact and pluralistic ignorance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(1), 91–17.

Shnabel, N., & Nadler, A. (2008). A needs-based model of reconciliation: Satisfying the differential emotional needs of victim and perpetrator as a key to promoting reconciliation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(1), 116–132. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.1.116

Sidanius, J., Levin, S., Federico, C. M., & Pratto, F. (2001). Legitimizing ideologies: The social dominance approach. In J. T. Jost & B. Major (Eds.), The psychology of legitimacy: Emerging perspectives on ideology, justice, and intergroup relations (pp. 307–331). Cambridge University Press.

Singer, T., Critchley, H. D., & Preuschoff, K. (2009). A common role of insula in feelings, empathy and uncertainty. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(8), 334–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.05.001

Stell, A. J., & Farsides, T. (2016). Brief loving-kindness meditation reduces racial bias, mediated by positive other-regarding emotions. Motivation and Emotion, 40(1), 140–147.

Stinson, L., & Ickes, W. (1992). Empathic accuracy in the interactions of male friends versus male strangers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62(5), 787–797. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.62.5.787

Stürmer, S., Snyder, M., Kropp, A., & Siem, B. (2006). Empathy-motivated helping: The moderating role of group membership. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(7), 943–956. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206287363

Tajfel, H. (1982). Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annual Review of Psychology, 33, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.33.020182.000245

Tajfel, H., Billig, M., Bundy, R., & Flament, C. (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1(2), 149–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420010202

Tajfel, H. E. (1978). Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. Academic Press.

Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories: Studies in social psychology. Cambridge University Press

Terrizzi, J. A., Jr., & Shook, N. J. (2020). An evolutionary evoked disease-avoidance strategy. In J. R. Liddle & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of evolutionary psychology and religion (pp. 198–212). Oxford University Press.

Tincher, M. M., Lebois, L. A., & Barsalou, L. W. (2015). Mindful attention reduces linguistic intergroup bias. Mindfulness, 7, 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0450-3

Toi, M., & Batson, C. D. (1982). More evidence that empathy is a source of altruistic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(2), 281. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.43.2.281

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (2010). Groups in mind: The coalitional roots of war and morality. In H. Høgh-Olesen (Ed.), Human morality and sociality: Evolutionary and comparative perspective (pp. 191–234). Palgrave Macmillan.

Trautwein, F. M., Naranjo, J. R., & Schmidt, S. (2014). Meditation effects in the social domain: Self-other connectedness as a general mechanism? In S. Schmidt, H. Walach (Eds.), Meditation – neuroscientific approaches and philosophical implications (pp. 175–198). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01634-4

Van Dam, N. T., Van Vugt, M. K., Vago, D. R., Schmalzl, L., Saron, C. D., Olendzki, A., Meissner, T., Lazar, S. W., Kerr, C. E., Gorchov, J., Fox, K. C. R., Field, B. A., Britton, W. B., Brefczynski-Lewis, J. A., & Meyer, D. E. (2018). Mind the hype: A critical evaluation and prescriptive agenda for research on mindfulness and meditation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(1), 36–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617709589

van Leeuwen, E., & Täuber, S. (2011). Demonstrating knowledge: The effects of group status on outgroup helping. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(1), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.09.008

van Doorn, J., Zeelenberg, M., & Breugelmans, S. M. (2014). Anger and prosocial behavior. Emotion Review, 6(3), 261–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914523794

Varela, F. J., & Depraz, N. (2003). Imagining: Embodiment, phenomenology, transformation. In B. A. Wallace (Ed.), Buddhism & science: Breaking new ground (pp. 195–230). Columbia University Press.

Vorauer, J. D., Gagnon, A., & Sasaki, S. J. (2009). Salient intergroup ideology and intergroup interaction. Psychological Science, 20(7), 838–845. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02369.x

Weisz, E., & Cikara, M. (2020). Strategic regulation of empathy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences., 24(3), 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2020.12.002

Wilson, T. D., & Brekke, N. (1994). Mental contamination and mental correction: Unwanted influences on judgments and evaluations. Psychological Bulletin, 116(1), 117–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.117

Winning, A. P., & Boag, S. (2015). Does brief mindfulness training increase empathy? The role of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 492–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.07.011

Zaki, J. (2014). Empathy: A motivated account. Psychological Bulletin, 140(6), 1608–1647. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037679

Zaki, J., & Cikara, M. (2015). Addressing empathic failures. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(6), 471–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721415599978

Zaki, J., & Mitchell, J. P. (2013). Intuitive prosociality. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(6), 466–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721413492764

Zeidan, F., Emerson, N. M., Farris, S. R., Ray, J. N., Jung, Y., McHaffie, J. G., & Coghill, R. C. (2015). Mindfulness meditation-based pain relief employs different neural mechanisms than placebo and sham mindfulness meditation-induced analgesia. Journal of Neuroscience, 35(46), 15307–15325. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2542-15.2015

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DRB: conducted literature search and wrote the paper. KR, GT, and AMCB: collaborated in the literature search as well as writing and editing of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berry, D.R., Rodriguez, K., Tasulis, G. et al. Mindful Attention as a Skillful Means Toward Intergroup Prosociality. Mindfulness 14, 2471–2484 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01926-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01926-3