Abstract

Objectives

Compassion science has been informed and guided by Buddhist perspectives, but has yet to fully account for certain key Buddhist ideas about compassion. Skillful means and fierce compassion represent two such ideas, both of which pertain to compassionate actions that may not always appear compassionate to recipients or observers.

Methods

To better account for the variety of compassionate behavior evident in the Buddhist traditions, including but not limited to skillful means and fierce compassion, this paper reviews relevant theory and findings from compassion science through the lens of the Big Two Framework. The Big Two Framework distinguishes between two core dimensions of social cognition, namely communion (i.e., warmth, morality, and expressiveness) and agency (i.e., dominance, competence, and instrumentality).

Results

The Big Two Framework’s fundamental distinction between communion and agency appears useful for delineating forms of compassionate behavior. Additionally, the framework is helpful for considering behavior from actor versus recipient/observer perspectives, making it well-suited to account for compassionate actions that may not appear compassionate.

Conclusions

Reflecting on compassion in relation to the Big Two maps a richer understanding of the social cognition underlying diverse forms of compassionate behavior and offers an empirically tractable framework and terminology for advancing research on understudied expressions of compassion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Scientific interest in compassion, both as an innate characteristic and trainable capacity of mind, has grown substantially over the last decade (Seppälä et al. 2017). Much of this research has been informed by Buddhist views and perspectives on compassion, similar to the important role of Buddhist thinking in the science of mindfulness (Lavelle 2017; Quaglia et al. 2020). However, as with mindfulness, certain key Buddhist ideas about compassion appear less represented in the scientific literature in ways that may limit the understanding, effectiveness, and applied benefits of compassion training. Examples from recent work include the need for a more relational approach within Western compassion training (Condon and Makransky 2020), how an overemphasis on divided conceptualizations of compassion may result in gaps in understanding (Quaglia et al. 2020, 2021), and that the scientific construct of self-compassion may be incompatible with the overall goals of Mahayana Buddhist compassion training (Dunne and Manheim 2022). Here I draw on two ideas from Buddhism, namely skillful means and fierce compassion, as guiding concepts for advancing research on the role of compassion in certain kinds of challenging social situations—that is, situations in which the most effective compassionate action is unclear or for which perceptions of someone’s action may differ greatly depending on whose perspective we take.

To do so, I reflect on compassion through the lens of the Big Two Framework (Abele and Wojciszke 2007; Abele et al. 2021; Fiske et al. 2007; Paulhus and Trapnell 2008), a social cognitive framework for distinguishing two fundamental dimensions of content within social cognition, namely communal versus agentic content. The Big Two may offer a helpful lens for compassion given its usefulness for understanding a wide range of other social phenomena, such as impression formation (Asch 1946; Rosenberg et al. 1968), leadership (Bass, 1990; Bertolotti et al. 2013), and personality (Blackburn et al. 2004; Saucier 2009). Additionally, the framework applies to distinguishing social behavior from both actor and observer/recipient perspectives (Abele and Wojciszke 2007, 2014), making it well-suited for considering compassionate behavior that may not appear compassionate to recipients or observers. Ultimately, a Big Two analysis of compassion may offer a tractable, empirically based framework and terminology for guiding more research on compassionate behavior that is not readily perceived to be nice, kind, or gentle.

From Compassion to Compassionate Behavior

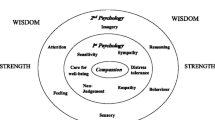

How best to define compassion is an important and ongoing area of inquiry for compassion science (e.g., Mascaro et al. 2020; Strauss et al. 2016). His Holiness the Dalai Lama (1995), who has long encouraged and helped to guide compassion science from a Buddhist view, has defined compassion as, “An openness to the suffering of others with a commitment to relieve it.” From an evolutionary perspective, Gilbert (2014) has similarly defined compassion as a “sensitivity to suffering in self and others with a commitment to try to alleviate and prevent it.” Both perspectives emphasize awareness of, and motivation to alleviate, suffering—two components commonly found in scientific definitions of compassion. Across definitions found in compassion science, it is common to consider separable components of compassion such as (1) acknowledging the presence of suffering; (2) feeling empathic concern for the one suffering; and (3) embodying an intentional readiness to alleviate suffering if possible (Gilbert 2015, 2020; Goetz et al. 2010; Jazaieri et al. 2013; Kanov et al. 2004; Strauss et al. 2016). While the exact number and type of components for compassion differs between perspectives, most emphasize a combination of cognitive, affective, and conative (motivational) processes, as well as a central focus on alleviating suffering.

The three components of compassion emphasized here are also clearly evident in how compassion is commonly trained in Western contexts, through meditation practices such as lovingkindness and tonglen (Quaglia et al. 2020). While lovingkindness is distinct from compassion in Buddhism—with the former emphasizing wishes for happiness and the latter emphasizing the reduction of suffering—more secular approaches to compassion training often include lovingkindness meditation as part of compassion training (Quaglia et al. 2020). During lovingkindness meditation, a trainee may be instructed to bring to mind someone who is going through a difficult time, cultivating greater awareness of suffering (cognitive component). Next, they are commonly instructed to focus on generating feelings of goodwill for the one who is suffering (affective component), alongside wishes for them to be free from suffering (conative component). Similar practices may be used to cultivate self-compassion, with a focus on noticing, feeling for, and wishing to alleviate one’s own suffering (Neff 2003, 2012). Thus, depending on whose suffering is focal, these components appear central to cultivating self-compassion, compassion for others, or some combination of compassion orientations (Quaglia et al. 2020, 2021).

Of the three components of cognitive, affective, and conative, the one most pertinent to the topic of this paper is the conative, or motivational, component, since it connects the personal experience of compassion with its behavioral expressions (cf. Adie et al. 2021). As presented here, compassionate behavior is defined as goal-directed behavior that is compassion-based—that is, the behavior stems from noticing suffering, feeling for the one who is suffering, and desiring to alleviate that suffering. Thus, the ultimate goal of compassionate behavior is to reduce suffering. Depending on personal, social, and situational factors, this goal can apply to one’s own or others’ suffering, as well as to the alleviation of suffering over the short- or long-term. Defined in this way, compassionate behavior represents a means to an end, and is distinguishable by qualities of the actor’s perspective (i.e., the one who is experiencing and acting from compassion). This approach is also consistent with research on other sorts of goal-directed behavior such as emotion regulation (cf. Gross 2013, 2015). However, it does not account for the success or impact of compassionate behavior, making it important to consider the success of compassionate behavior as a separate dimension. Alternatively, researchers could develop measures of compassionate behavior that not only assess the actor’s perspective, but also the impact on others in a variety of ways and at multiple timescales.

Skillful Means and Fierce Compassion

Buddhist thinking has been central in guiding much of the scientific study on compassion and its training (Lavelle 2017). Despite many fruits of the dialogue between Buddhism and compassion science, the field has yet to fully account for certain key concepts about compassion represented within Buddhism. Skillful means (upaya-kaushalya) is one such key concept from traditional Mahayana Buddhist teachings that pertains primarily to the variety of means a dedicated compassion practitioner may use to alleviate suffering (Cheng 2014; Federman 2009; McRae 2004; Schroeder 2004). As with mindfulness (cf. Quaglia et al. 2015), definitions and interpretations of the term skillful means can vary within Buddhism (Federman 2009; Matsunaga and Matsunaga 1974; Simmer-Brown 1992). Yet, across various interpretations of the term, skillful means appears fundamentally connected to both the cultivation of compassion and its diverse behavioral expressions (Simmer-Brown 1992), and compassion is arguably what is most essential to skillful means (Schroeder 2004).

Applied to compassion, skillful means encompasses the development and use of diverse skills, strategies, and tactics needed to benefit others in ways that are context-sensitive, and can be flexibly employed according to the uniqueness of individuals and situational demands (Cheng 2014; McRae 2004; Schroeder 2004). Skillful means also include actions that may not always appear compassion-based from the outside, due to a knowledge gap between compassionate actors and observers/recipients (Federman 2009). For example, the Lotus Sutra includes a parable wherein the Buddha describes the usefulness of “white lies” to lure children out from a burning building, lest they be killed in the fire (Federman 2009). By centering on the compassionate goal for misleading the children (i.e., to save them from suffering a horrendous death), this parable highlights the central importance of both motivation and context for recognizing compassionate behaviors (Federman 2009), rather than limiting compassion to a prescribed, context-general set of actions.

A related concept of Tibetan Buddhist teachings is that of fierce compassion (Makransky 2016), which also has yet to receive ample attention in compassion science and training. While the word “fierce” may carry connotations of anger or aggression, the concept of fierce compassion is meant to encompass expressions of compassion that may be strong, forceful, confrontational, and protective (Gilbert 2015; Makransky 2016; Neff 2018). Some fierce expressions of compassion have been previously explored and trained as part of the courage of compassion (Gilbert 2014, 2015), such as when resisting pressures to behave non-compassionately. Accordingly, courage is considered a key component of compassion in many training programs (Gilbert, 2009; 2015; Jinpa 2015). Since fierce or courageous forms of compassionate behavior are rooted foremost in compassion, rather than anger or aggression, they are primarily motivated by the goal to alleviate suffering (Makransky 2016). Consider the following passage from renowned Buddhist teacher Jack Kornfield (2009):

Compassion is not foolish. It doesn’t just go along with what others want so they don’t feel bad. There is a yes in compassion, and there is also a no, said with the same courage of heart. No to abuse, no to violence, both personal and worldwide. The no is said not out of hate but out of unwavering care. Buddhists call this the fierce sword of compassion.

As is evident in this quote, fierce compassion acknowledges that, depending on the situation, one’s goal to alleviate suffering may require behaviors that are not experienced as compassionate on the receiving end, or may “feel bad” to the recipient person. It is also noteworthy that fierce compassion is thought to buffer against various forms of ineffective compassionate behavior, which have been described as “enabling” (Khyentse 2003), “idiot compassion” (Trungpa 2008), or “sentimental compassion” (Thurman 2006). Accordingly, fierce and courageous forms of compassion may be especially important to the context of social justice, where alleviating suffering often entails confronting the harmful actions of others (Gilbert 2015; Makransky 2016; Neff 2018).

Thus, both skillful means and fierce compassion represent understudied ideas about compassion from Buddhism that offer a helpful challenge to oversimplified views on compassionate behavior as synonymous with nice, gentle, or submissive behavior, a potential misconception about compassion previously recognized in compassion research (Catarino et al. 2014; Gilbert et al. 2017; Gilbert 2020). Skillful means and fierce compassion also share in common the likelihood of being perceived or evaluated differently from actor versus observer/recipient perspectives, highlighting the importance of perspective when aiming to study them scientifically. As will be explored next, in the language of the Big Two, these distinctions between compassion and niceness, gentleness, and so on pertain to relations between compassion, communion, and agency. Additionally, the Big Two Framework acknowledges the potential for divergence in how behaviors are perceived between actor and observer/recipient perspectives.

The Big Two

Social scientists have long recognized that people navigate their social world by relying on two fundamental dimensions of social cognitive content (Bakan, 1966; Abele and Wojciszke 2007, 2014; Fiske et al. 2007). The Big Two Framework (Abele et al. 2021; Paulhus and Trapnell 2008) is a metatheoretical perspective that aims to encompass and integrate research on these two dimensions, commonly using the terms communion and agency to distinguish between them. Generally speaking, communion concerns qualities and behaviors important for relationality and “getting along,” such as friendliness and care, whereas agency pertains to qualities and behaviors for goal pursuit and “getting ahead,” such as assertiveness and task accomplishment (Abele and Wojciszke 2014; Abele et al. 2021). Yet across different areas of investigation, researchers have relied on a variety of terms to distinguish between these dimensions, including warmth-dominance, morality-competence, expressiveness-instrumentality, femininity-masculinity, social goodness-intellectual goodness, and horizontal-vertical (for reviews, see Abele et al. 2021; Abele and Wojciszke 2014). Depending on the domain to which they are applied, different aspects of the Big Two may be more salient. As examples, researchers studying perceivers’ ratings of facial structure have identified two underlying factors to be trustworthiness-dominance (Willis and Todorov 2006), whereas the study of gender has commonly delineated the Big Two in terms of feminine-masculine (Bem 1974). As applied to this paper, the Big Two may be understood as an inclusive and flexible framework that helps to organize and integrate research on two core dimensions of social cognitive content found across a wide variety of social phenomena.

Most germane to the topic of compassion, it has been argued that communal and agentic behavior might be distinguished by tendencies toward other-profitability and self-profitability, respectively (Abele and Wojciszke 2007, 2014; Peeters 2005). Specifically, since agentic behavior is evaluated primarily by its adaptive potential for the acting individual, it tends toward self-profitability, whereas communal behavior is rooted in its value to others, and therefore tends to be evaluated as other-profitable. However, this has been shown to be an oversimplification, with research demonstrating that agentic behavior may be instrumental to achieving an other-profitable goal (Abele and Wojciszke 2007; Frimer et al. 2011). For example, research on moral exceptionality has found that moral exemplars tend to integrate agency and communion, relying on agentic behavior in service of communal pursuits (Frimer et al. 2011, 2012). This highlights an important caveat for a Big Two analysis of compassion, namely that complex social situations may require sequencing or blending communal and agentic behaviors (cf. Frimer et al. 2011, 2012). Indeed, research has shown that singular, unmitigated forms of either communal or agentic behavior can be detrimental (Helgeson and Fritz 1999).

Overall, the Big Two are considered vital dimensions of the social mind, essential to people’s capacities to understand themselves and each other in the context of social interaction (Abele and Wojciszke 2014; Abele et al. 2021). Yet, as core aspects of social cognition, they are also primarily subjective and perceiver-dependent (cf. Barrett 2012), whether in the subjective experience of how an individual actor perceives their own actions, or how a recipient/observer perceives the actions of others. Consistent with this, research has found there to be a common divergence in how an action is perceived between actors (self-perception) and recipient/observers (perception of others). The Dual Perspective Model (DPM) holds that communion and agency are differentially linked to actor versus recipient/observer perspectives (Abele and Wojciszke 2007, 2014). Specifically, the DPM states that communal content is primary when evaluating behavior from the recipient/observer perspective, whereas agentic content is primary from the actor perspective. This asymmetry in how actions may be perceived makes it important to consider multiple perspectives—actor and recipient/observer—when applying the Big Two to the topic of compassion.

One End, Many Means

With this review, we can now conduct an initial analysis of compassionate behavior through the lens of the Big Two, and thereby reflect on the variety of compassionate behaviors one may use to pursue their goal of alleviating suffering, including those described in Buddhism as skillful means and fierce compassion. To do so, I first consider compassionate behavior in relation to three adjective pairs that have been commonly relied on to distinguish qualities of communal and agentic behavior in the Big Two literature. While none of these pairs fully encompass the communion-agency distinction, individually or in combination, they can each help to organize relevant theory and findings from compassion science that may be useful for delineating communal and agentic forms of compassionate behavior. Descriptions and representative findings for these communal and agentic qualities are presented in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. After reviewing relevant theory and findings in relation to these adjective pairs, I then consider how the Big Two’s focus on distinguishing actor and recipient/observer perspectives may offer additional insights for compassion science. Importantly, this analysis will focus primarily on the individual and interpersonal levels of analysis, and does not account for more systemic and cultural factors that may shape how compassion is experienced and expressed (cf. George 2014; Steindl et al. 2020).

Warmth Versus Dominance

In the context of the Big Two, warmth pertains to nurturance, cooperation, and “getting along” (Abele et al. 2021; Abele and Wojciszke 2014; Wiggins 1979). Consistent with this quality of communion, ample research has linked compassion and its behavioral expressions to warm, affiliative, and affectionate behaviors (Gilbert 2015, 2019; Goetz et al. 2010). Evolutionary perspectives on this subject hold that compassion evolved as part of a distinct affective experience that promotes cooperation, protection of the weak and vulnerable, and care for those suffering (Goetz et al. 2010). This includes behavioral expressions such as soothing and touch that correspond with social approach motivation (Goetz et al. 2010). Research relying on word sorting has found that participants group compassion together with words such as sympathy, kindness, tenderness, and warmth (Campos et al. 2009), and subjective experiences of induced compassion are likewise linked with sympathy, tenderness, and warmth (Condon and Barrett 2013). Studies on compassion training also support the link between the cultivation of compassion and warmth. In one example, Ashar et al. (2016) found that, compared with two active control conditions, compassion meditation increased feelings of tenderness toward individuals facing hardship, together with increasing the amount of donations to them. Regarding neuroscientific research, Klimecki et al. (2013) studied the effects of compassion training in response to videos of others in distress, finding that compassion training increased activation in areas of the brain associated with love and affiliation. Considered together, prior theory and empirical research on compassion strongly supports the link between compassion and warmth, particularly for targets in distress or facing hardship.

As an agentic counterpart to warmth, dominance is associated with power, assertiveness, and “getting ahead” (Abele et al. 2021; Abele and Wojciszke 2014; Wiggins 1979). Thus far, compassion research seems to have focused less on dominance per se, and more so on refuting the link between compassion and submissive behavior. This may be aimed at misconceptions outside the scientific community that compassion entails submissiveness, as revealed by research on the fears of compassion (Gilbert et al. 2011; Kirby et al. 2019). For example, this research has found that people will endorse statements such as, “Being too compassionate makes people soft and easy to take advantage of,” “People will take advantage of you if you are too forgiving and compassionate,” and “I fear that being too compassionate will make me an easy target” (Gilbert et al. 2011). Running counter to such statements, research has examined “submissive compassion,” a form of pseudo-compassionate behavior focused on appearing nice or wanting to be liked (Catarino et al. 2014). In two studies, researchers found that this sort of submissive behavior was linked with unfavorable outcomes, such as shame, self-criticism, and depression, whereas “genuine” compassion was associated with more favorable outcomes (Catarino et al. 2014; Gilbert et al. 2017). Similarly, research has found that genuine self-compassion is negatively related to submissive behaviors (Akin 2009; Eraydın and Karagözoğlu 2017).

Overall, studying the relation between compassion and submissive behavior is important, but countering the tendency to associate them may require more direct research on dominant behavioral expressions of compassion, including fierce compassion. As Gilbert (2014) writes, “Compassion is not about the avoidance of anger or being stuck in a weak submissive position. Compassion involves developing the courage to be open to our anger and rage” (p. 33). Additionally, further research on this topic seems poised to reveal a more complex and nuanced relationship between compassion and dominance, compared to that of compassion and warmth. For example, Van Kleef et al. (2008) found that participants with more perceived power exhibited less compassionate behavior when engaging with others who were suffering. Thus, even if compassion is associated with dominant behavior in certain situations, it will remain important to consider how dominance might also interfere with compassion.

Morality Versus Competence

Morality pertains to behavior that is sensitive to the needs and goals of others, as well as to moral norms such as fairness and loyalty (Abele and Wojciszke 2014; Reeder and Brewer 1979). From an evolutionary perspective, it has been argued that compassion is central to the development of moral judgment and behavior, perhaps even serving as a “moral barometer” (Gilbert 2019; Goetz et al. 2010). Consistent with this perspective, research has found that down-regulating feelings associated with compassion can create a sense of dissonance with one’s moral self-concept (Cameron and Payne 2012). Specifically, participants instructed to regulate feelings related to compassion in response to human distress subsequently devalued morality or relaxed their beliefs in moral norms (Cameron and Payne 2012). Regarding compassion’s role in enacting moral behavior, compassion training can increase prosocial behavior in games designed to assess helping behavior (Leiberg et al. 2011; Weng et al. 2013). Additionally, two studies examined the effects of compassion training in the context of an economic game task that entailed fairness violations (McCall et al. 2014; Weng et al. 2015), finding that compassion training increased altruistic redistribution to victims of unfairness. These studies also found that compassion training did not decrease the amount of norm-reinforcing punishment of fairness violators, indicating that compassion may give rise to distinct patterns of moral responding to both victims and transgressors of social norm violations.

Competence is an agentic quality associated with skillfulness, efficiency, task performance, and goal achievement (Abele and Wojciszke 2014; Wojciszke 2005). There appear to be two ways the connection between compassion and competence has been explored to date. First, compassion can be assessed in terms of how competently one can enact effective compassionate behavior. This is consistent with an evolutionary perspective, which considers effective compassion to depend on a variety of socially intelligent competencies that are important for taking actions to reduce suffering (Gilbert et al. 2017). Indeed, research has shown those higher in cognitive empathy tend to enact more beneficial empathy-driven behaviors compared with those lower in cognitive empathy (Gilbert et al. 2017). Extending this understanding into an applied context, the Compassion Competence Scale (Lee and Seomun 2016) is a measure for studying the role of different compassion-related competencies among medical professionals. The scale assesses compassion competence according to three subfactors: (1) communication (e.g., “I am aware of how to communicate with patients to encourage them”); (2) sensitivity (e.g., “I am well aware of changes in patients’ emotional condition”); and (3) insight (e.g., “I am intuitive about patients because of my diverse clinical experience”).

Second, competence can be viewed as an outcome of compassion or compassion training. For example, research has demonstrated links between compassion and job performance among teachers (Aboul-Ela 2017), nurses (Chu 2017), and employees of private companies (Ko and Choi 2019). Being on the receiving end of compassion has likewise been found to improve job performance (Chu 2016; Eldor 2018), suggesting possible mutual benefits for the competence of both extending and receiving compassion in the workplace. Another broad area of competency that has been emphasized in compassion research is emotion regulation, which pertains to how successful individuals are in modulating emotions according to their goals (Gross 2015). As examples, research has found that compassion meditation improves social emotion regulation (Engen and Singer 2015; Klimecki et al. 2013), self-compassion can increase the efficacy of key emotion regulation strategies (Diedrich et al 2016), and compassion training can enhance one’s capability to achieve emotion regulatory goals (Jazaieri et al. 2018). In addition to questions about whether compassion promotes competence, research is needed to understand the underlying mechanisms driving compassion’s effects, such mechanisms may include greater motivation or enhanced cognitive control. This research gap is especially evident when comparing studies on training in compassion with mindfulness, for which cognitive task performance has been a key research focus (Chiesa et al. 2011; Grossenbacher & Quaglia, 2017). As one notable exception, researchers examined the effects of lovingkindness meditation on Stroop Task performance, and found that lovingkindness resulted in improvements in cognitive control (Hunsinger et al. 2013).

Expressiveness Versus Instrumentality

In a Big Two Framework, expressive behavior is associated with group harmony, affection, and eagerness to soothe hurt feelings (Abele and Wojciszke 2014; Colley et al. 2009).

If compassion is associated with expressiveness, then it should heighten the scope and scale of affective and behavioral responsiveness to those who are suffering. A growing body of findings, using diverse methods, supports this connection. First, regarding the scope of such responsiveness, a study examined the effects of lovingkindness meditation on implicit bias toward stigmatized outgroups (Kang et al. 2014), finding lower implicit bias toward both homeless and black individuals following lovingkindness meditation. Regarding the degree of sensitivity to suffering, compassion training has been shown to heighten neural response (Lutz et al. 2008), as well as facial action displays of sympathetic concern (Rosenberg et al. 2015) to sounds or videos of others in distress, respectively. This heightened sensitivity to suffering also appears to translate into more expressive behavior, such as was found in studies linking compassion training with greater altruistic redistribution to victims of unfairness (McCall et al. 2014; Weng et al. 2015), as well as to strangers in need (Ashar et al. 2016). In a more ecologically valid test of compassion’s effects on expressive behavior, Condon et al. (2013) examined the effects of meditation training (including compassion) on whether one would give up their seat to someone on crutches, who was visibly wincing in pain. Findings confirmed that meditation increased the likelihood of offering one’s seat to the person in pain.

In Big Two research, instrumentality has been considered an agentic counterpart to expressiveness, pertaining to goal-oriented behaviors that serve as a means to an end (Abele and Wojciszke 2014; Frimer et al. 2012). In the context of compassion, instrumentality pertains to any short-term behavior that serves as a means toward a compassionate goal over a longer timeframe. A few studies within compassion science, alongside some noteworthy parallel findings from Big Two research, have found evidence for instrumental forms of compassionate behavior. Regarding findings on compassion per se, the aforementioned studies relying on economic games provide what may be the strongest evidence for instrumental compassionate behavior. Specifically, both McCall et al. (2014) and Weng et al. (2015) found that compassion training increased recompensating victims of unfairness, but was not associated with decreased punishment of norm violators, supporting the view that compassion does not reduce instrumental punishment behavior. Most relevant to instrumentality, McCall et al. (2014) found that such punishment behavior among compassion practitioners occurred in the relative absence of anger, a finding they attribute to a shift from “sanctioning as a function of vengeful and retributive motives (i.e., punishment to punish the transgressor) to sanctioning in order to restore justice and equity (i.e., to solve the problem)” (p. 9).

Overall, these findings are consistent with research on the Big Two suggesting that agentic behavior (e.g., punishment of perpetrators) can be instrumental to long-term, prosocial goals (e.g., to restore social harmony; Abele and Wojciszke 2007). A noteworthy parallel finding comes from studies on what distinguishes moral exemplars from a similarly influential, but morally lacking, comparison group (Frimer et al. 2011, 2012). Rather than prosociality on its own distinguishing moral exemplars, it was found that influential moral figures—such as Rosa Parks, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and Mother Teresa—consistently leveraged agentic behavior in an instrumental fashion to achieve prosocial goals (Frimer et al. 2011, 2012). For example, Frimer et al. (2012) cite British suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst’s “fighting” (instrumental agency) for “the betterment of the human race” (prosocial goal). Together, these studies from compassion science and the Big Two literature provide initial evidence that agentic behavior can be instrumental to the achievement of compassionate goals, similar to how communal behavior can be used to achieve self-interested goals (Catarino et al. 2014; Gilbert et al. 2017).

Compassion from Two Perspectives

When one person behaves compassionately toward another, there are commonly at least two subjective perceptions and evaluations of that action. First, there is the individual’s own self-perception of the behavior (actor perspective), which holds unique insight and information regarding the thoughts, feelings, and goals that motivate their behavior (e.g., the goal to alleviate suffering). Second, there is the perspective of the target or recipient of that compassionate behavior—that is, the individual whose suffering is focal for the actor. Beyond these two, there is potential for other observers of compassionate behavior, who are neither the actor nor recipient, but who may have unique knowledge or relation to the actor or recipient. As mentioned earlier, the DPM (Abele and Wojciszke 2007, 2014) holds that these different perspectives matter for how a given behavior will be evaluated in relation to communion and agency. Specifically, communal content will receive more weight when evaluating behavior from the recipient/observer perspective because recipient/observers are more likely to benefit from communal traits and behaviors. Conversely, agentic content is given more weight when evaluating from the actors’ perspective, since actors tend to be more concerned with their own goal pursuit (Abele and Wojciszke 2014; Peeters 2005).

There are two broad implications of the DPM for understanding compassionate behavior through the lens of the Big Two. First, as noted earlier, both communal and agentic behaviors may be useful for achieving one’s compassionate goal of alleviating suffering. Therefore, as the DPM applies to compassion, there is less truth to the default evaluations of how much communion and agency benefit others versus oneself, respectively. Yet since these weightings of the Big Two are central to how social behaviors are perceived and evaluated (Abele and Wojciszke 2007, 2014), tendencies to associate communion with other-profitability and agency with self-profitability may persist in how compassionate behaviors are evaluated. Accordingly, all other things equal, we would expect recipients/observers to deem communal forms of compassionate behavior as more favorable, whereas the actor perspective would deem agentic forms of compassionate behavior more favorably. Second and relatedly, there is likely a larger divergence, between actor and recipient/observer perspectives for agentic forms of compassionate behavior when compared with communal forms. This is partially due to a real knowledge gap between actors and recipients/observers—the actor is aware their agentic behavior is motivated by prosocial goals, whereas the recipient/observer can only be aware of this through communication or inference. According to the DPM, this bigger gap in perceptions for agentic compassionate behavior will also be driven by the differential weightings of communion and agency between perspectives.

Overall, these two implications of the DPM converge to generate a number of interesting predictions about how different forms of compassionate behavior are perceived and evaluated. First, due to more divergence in perception between actors and recipients/observers, agentic compassionate behaviors may result in less social consensus than communal compassionate behaviors. Indeed, when rating how compassionate behaviors are, we might expect actors to rate agentic forms of compassion higher and recipients/observers to rate communal forms as higher. Second, based on these divergent perceptions, agentic forms of compassion may be associated with more controversy and conflict (Abele and Wojciszke 2014). This could manifest behaviorally in a greater need for actors to communicate their compassionate intentions before, during, and after agentic compassionate behavior. Third, agentic compassionate behavior seems likely to entail more social risk than communal forms, since recipients/observers may mislabel these agentic actions as less compassionate or even as self-interested. Compassionate actors may therefore be disincentivized to engage in agentic compassionate behavior in social contexts for which they anticipate social costs. On the other hand, agentic compassionate behavior may be more likely when actors are trusted or hold positions of power.

Additional Implications for Compassion Science

To date, compassion science has made progress in developing a more robust understanding of compassion as an innate yet trainable aspect of the human mind. This work has been greatly facilitated by the perspectives of Buddhist traditions, for which compassion and its training have long been central to the soteriological goal of ending suffering. This established research offers a supportive foundation for exploring the greater diversity of behavioral expressions of compassion found within Buddhist traditions. Accordingly, this paper has presented a Big Two analysis of compassion in order to see what insights could be gleaned about particular expressions of compassion that have received less empirical attention, including but not limited to skillful means and fierce compassion. Examining compassion through this lens reveals that compassion can be expressed behaviorally in both communal and agentic forms, with existing theory and incipient data overall consistent with traditional views on the potential for compassion to manifest in a variety of behavioral expressions. This Big Two analysis also highlights the importance of considering compassionate behavior with respect to one’s perspective, since the same behavior can be evaluated in different ways depending on whether one is an actor, recipient, or observer of compassionate behavior. What follows is an exploration of additional insights offered by analyzing compassionate behavior in relation to the Big Two Framework.

Is Compassion Science Biased Toward Communion?

This Big Two analysis of compassionate behavior raises a number of new and interesting questions for future research, and perhaps especially with regard to agentic expressions of compassion. Foremost, it seems important to consider the relative emphasis of compassion science on communion versus agency. Prior research on the Big Two has demonstrated that communal behavior tends toward other-profitability, whereas agentic behavior tends toward self-profitability, an ingrained association that appears central to how perceivers cognize their social world (Abele and Wojciszke 2007, 2014). Compassion’s intrinsic link with other-profitability may therefore bias thinking about compassion toward communion because communal behaviors more readily come to mind when reflecting on compassion. Additionally, the affective component of compassion has been shown to include feelings of tenderness and warmth, which are commonly perceived as part of communion. Therefore, compassion may be associated with communion more than agency when appraised from an affective perspective, and this may shape people’s views of compassionate behavior. Agentic expressions of compassion are also often instrumental—meaning that the achievement of one’s compassionate goals (to reduce suffering) may not be immediate nor obvious. This instrumentality adds another layer of complexity for assessing the effectiveness of compassionate behavior. Finally, an examination of compassion through DPM theory reveals a greater mismatch between actor and recipient/observer perspectives when compassionate behavior is agentic. This larger actor-observer gap may make it more challenging to study agentic forms of compassion in ways that account for how these behaviors are perceived from multiple perspectives.

Despite a number of reasons for why compassion may be more readily associated with communion than agency, this Big Two analysis has revealed how the connection between compassion and communion is far from comprehensive. By considering theory and findings from compassion science that express agency—namely dominance, competence, and instrumentality—we see evidence for agentic compassionate behavior that is consistent with scientific and traditional Buddhist perspectives. Without more attention to such agentic compassionate behavior, there could be a risk of reinforcing a simplified understanding of compassionate behavior as synonymous with communal behavior. This may be especially detrimental when the association between compassion and communion serves as a barrier for certain audiences or domains of society that may strongly benefit from compassion training. For example, Kirby and Kirby (2017) examined compassion through an evolutionary perspective and found that teenage boys may be reluctant to develop compassionate identities due to misconceptions about the links between compassion and masculinity (an agentic quality). Similarly, Ramon et al. (2020) examined relationships between self-compassion and masculinity among veterans, finding that masculine norms may function as a psychological barrier to self-compassion.

Compassion and Social Justice

Social justice is another key area of application for compassion training that risks being underserved when communal expressions of compassion are centered. As mentioned earlier, fierce compassion seems particularly relevant in the context of social justice (Makransky 2016), and a Big Two analysis can help us better frame the relationships between compassion and social justice within an existing, empirically derived framework. By conceptualizing diverse kinds of strong, forceful, confrontational, or protective compassionate behaviors as agentic compassionate behaviors (instead of the Buddhist term, fierce compassion), we can better distinguish them from similar behaviors that may be rooted in anger or aggression (Makransky 2016). This is because the goal of alleviating suffering often entails confronting the harmful actions of others (Gilbert 2015; Makransky 2016; Neff 2018), which depends critically on the capacity to leverage agentic behavior in service of a compassionate goal. As reviewed earlier, research on compassionate responses to social injustice has demonstrated the reliance of agentic behavior alongside a relative absence of anger (McCall et al. 2014), and moral exemplars appear distinguishable from others by their capacity to wield agentic behaviors to combat social injustice of various kinds (Frimer et al. 2011, 2012). Reflecting on the links between compassion and social justice also underscores the need for more research on how systemic and cultural factors may shape compassionate behavior (cf. George 2014; Steindl et al. 2020).

Agentic Self-Compassion

Although the primary focus for this Big Two analysis has been other-oriented compassion, a similar analysis could be done for self-compassion. For example, regarding the agentic quality of dominance, two studies on self-compassion have revealed negative correlations with submissive behavior (Akin 2009; Eraydın and Karagözoğlu 2017), suggesting higher self-worth with self-compassion may support and maintain dominant behavioral expressions (e.g., assertiveness) when such actions align with reducing one’s own suffering. Research also suggests that self-compassion may engender competence by promoting a more accepting and positive attitude toward oneself and one’s mistakes, rather than more self-critical and evaluative responses (Mosewich et al. 2019). Consistent with this perspective, a study on self-improvement motivation found that self-compassion can increase one’s engagement with self-improvement when confronted with one’s mistakes (Breines and Chen 2012). This finding also highlights links between instrumentality and self-compassion, which may be important for differentiating self-compassionate behaviors from self-gratification. It has been said that self-compassion is “less about doing what feels good all the time, and more about doing that which is good for me, even if it is difficult” (Adie et al. 2021, p. 1748; Breines and Chen 2012).

Revisiting Skillful Means and Fierce Compassion

Equipped with related concepts and theory from the Big Two literature, we can now revisit the topics of skillful means and fierce compassion. As presented in this paper, what appears most essential to compassion is not a prescribed set of behaviors, but rather a distinct cognitive and emotional experience paired with a goal to alleviate suffering. This understanding of compassion leaves room for it to be expressed in a wide variety of behaviors that can support the achievement of compassionate goals. As Gilbert and Mascaro (2017) write, “Thinking about compassion as a form of courage can help set against the view that compassion is about kindness, softness, and gentleness. Those are ways of being compassionate but are not compassion itself” (p. 414). This statement echoes the sentiment that the inner experience of compassion is distinct from its outward behavioral expressions or “ways of being” that derive from compassion. Viewed through the Big Two, the diverse set of compassionate behaviors includes agentic behaviors, which may not be as readily perceived as compassionate to recipients/observers. It is this concept of agentic compassionate behavior that seems especially helpful for understanding skillful means and fierce compassion.

Both skillful means and fierce compassion represent forms of compassionate behavior from Buddhist thinking that do not fit neatly with the idea that compassion is always characterized by niceness, gentleness, or softness, a potential myth about compassion recognized previously (Catarino et al. 2014; Gilbert et al. 2017; Gilbert 2020). Additionally, as understood in Buddhist teachings, skillful means and fierce compassion are likely to be perceived differently depending on one’s perspective, since the compassionate actor may hold unique knowledge about the motivation for their actions. Considered together, these features appear strongly aligned with insights from the Big Two literature. Specifically, both skillful means and fierce compassion may be framed as concepts or categories from Buddhism that are primarily about agentic compassionate behavior. Connecting skillful means and fierce compassion to the construct of agency helps us to understand what distinguishes them from communal expressions of compassion, namely through their association with qualities such as dominance, competence, and instrumentality. Additionally, because agentic behaviors may be less likely to be deemed compassionate by recipients/observers, this framing provides explanatory power regarding the potential for agentic compassionate behaviors to be misinterpreted, controversial, or socially risky. Ultimately, this Big Two analysis may inform the next steps for research on topics such as skillful means and fierce compassion, both of which may be better construed as forms of agentic compassionate behavior within compassion science and perhaps also compassion training.

The purpose of this paper was to bring the literature of compassion and the Big Two together to provide novel insights about compassionate behavior. I was especially interested in research and findings relevant to understudied expressions of compassion evident in the Buddhist traditions, such as skillful means and fierce compassion. A Big Two analysis of compassionate behavior offers a useful conceptual division between communion and agency, which invites a more complete consideration of the wide variety of possible compassionate behaviors. This analysis offers a foundation for understanding how compassion may give rise to both communal and agentic behaviors, depending on what can best serve one’s goal to reduce suffering. Moreover, the Big Two helps to account for skillful means and fierce compassion within compassion science, providing new terminology and an empirical framework for advancing research on such agentic expressions of compassion. Considering the relevance of agentic compassionate behavior for countering myths about compassion that may preclude certain audiences from engaging in compassion and its training, further research on agentic compassionate behavior would be helpful.

References

Abele, A. E., & Wojciszke, B. (2007). Agency and communion from the perspective of self versus others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(5), 751.

Abele, A. E., & Wojciszke, B. (2014). Communal and agentic content in social cognition: A dual perspective model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 50, 195–255.

Abele, A. E., Ellemers, N., Fiske, S. T., Koch, A., & Yzerbyt, V. (2021). Navigating the social world: Toward an integrated framework for evaluating self, individuals, and groups. Psychological Review, 128(2), 290.

Aboul-Ela, G. M. B. E. (2017). Reflections on workplace compassion and job performance. Journal of Human Values, 23(3), 234–243.

Adie, T., Steindl, S. R., Kirby, J. N., Kane, R. T., & Mazzucchelli, T. G. (2021). The relationship between self-compassion and depressive symptoms: Avoidance and activation as mediators. Mindfulness, 1–9.

Akin, A. (2009). Self-compassion and submissive behavior. Egitim Ve Bilim, 34(152), 138.

Asch, S. E. (1946). Forming impressions of personality. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 41, 258–290.

Ashar, Y. K., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Yarkoni, T., Sills, J., Halifax, J., Dimidjian, S., & Wager, T. D. (2016). Effects of compassion meditation on a psychological model of charitable donation. Emotion, 16(5), 691.

Bakan, D. (1966). The duality of human existence. An essay on psychology and religion. Rand Mcnally.

Barrett, L. F. (2012). Emotions are real. Emotion, 12(3), 413–429.

Bass, B. (1990). The Bass & Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications (3rd ed.). Free Press.

Bass, B. M., & Bass, R. (2009). The Bass handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications. Simon and Schuster.

Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology, 42, 155–162.

Bertolotti, M., Catellani, P., Douglas, K., & Sutton, R. (2013). The “Big Two” in political communication: The effects of attacking and defending politicians’ leadership or morality. Social Psychology, 44, 118–129.

Blackburn, R., Renwick, S. J. D., Donnelly, J. P., & Logan, C. (2004). Big Five or Big Two? Superordinate factors in the NEO five factor inventory and the antisocial personality questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 957–970.

Breines, J. G., & Chen, S. (2012). Self-compassion increases self-improvement motivation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(9), 1133–1143.

Cameron, C. D., & Payne, B. K. (2012). The cost of callousness: Regulating compassion influences the moral self-concept. Psychological Science, 23(3), 225–229.

Campos, B., Shiota, M. N., Keltner, D., Gonzaga, G., Goetz, J. L., & Shin, M. (2009). Amusement, awe, contentment, happiness, love, pride, and sympathy: An empirical exploration of positive emotions in language, internal experience, and facial expression. Unpublished manuscript.

Catarino, F., Gilbert, P., MCewaN, K., & Baião, R. (2014). Compassion motivations: Distinguishing submissive compassion from genuine compassion and its association with shame, submissive behavior, depression, anxiety and stress. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 33(5), 399–412.

Cheng, F. K. (2014). Overcoming “sentimental compassion”: How Buddhists cope with compassion fatigue. Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies, 7.

Chiesa, A., Calati, R., & Serretti, A. (2011). Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(3), 449–464.

Chu, L. C. (2016). Mediating positive moods: The impact of experiencing compassion at work. Journal of Nursing Management, 24, 59–69.

Chu, L. C. (2017). Impact of providing compassion on job performance and mental health: The moderating effect of interpersonal relationship quality. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 49(4), 456–465.

Colley, A., Mulhern, G., Maltby, J., & Wood, A. M. (2009). The short form BSRI: Instrumentality, expressiveness and gender associations among a United Kingdom sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(3), 384–387.

Condon, P., & Barrett, F. L. (2013). Conceptualizing and experiencing compassion. Emotion, 13(5), 817.

Condon, P., & Makransky, J. (2020). Recovering the relational starting point of compassion training: A foundation for sustainable and inclusive care. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(6), 1346–1362.

Condon, P., Desbordes, G., Miller, W. B., & DeSteno, D. (2013). Meditation increases compassionate responses to suffering. Psychological Science, 24(10), 2125–2127.

Dalai Lama (1995). The power of compassion. Harper Collins.

Diedrich, A., Hofmann, S. G., Cuijpers, P., & Berking, M. (2016). Self-compassion enhances the efficacy of explicit cognitive reappraisal as an emotion regulation strategy in individuals with major depressive disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 82, 1–10.

Dunne, J. D., & Manheim, J. (2022). Compassion, self-compassion, and skill in means: A Mahāyāna perspective. Mindfulness. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01864-0

Eldor, L. (2018). Public service sector: The compassionate workplace—The effect of compassion and stress on employee engagement, burnout, and performance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 28(1), 86–103.

Engen, H. G., & Singer, T. (2015). Compassion-based emotion regulation up-regulates experienced positive affect and associated neural networks. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 10(9), 1291–1301.

Eraydın, Ş, & Karagözoğlu, Ş. (2017). Investigation of self-compassion, self-confidence and submissive behaviors of nursing students studying in different curriculums. Nurse Education Today, 54, 44–50.

Federman, A. (2009). Literal means and hidden meanings: A new analysis of skillful means. Philosophy East and West, 59(2), 125–141.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 77–83.

Frimer, J. A., Walker, L. J., Dunlop, W. L., Lee, B. H., & Riches, A. (2011). The integration of agency and communion in moral personality: Evidence of enlightened self-interest. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(1), 149–163.

Frimer, J. A., Walker, L. J., Lee, B. H., Riches, A., & Dunlop, W. L. (2012). Hierarchical integration of agency and communion: A study of influential moral figures. Journal of Personality, 80(4), 1117–1145.

George, J. M. (2014). Compassion and capitalism: Implications for organizational studies. Journal of Management, 40(1), 5–15.

Ghafarian, H., & Khayatan, F. (2018). The effect of training compassion focused therapy on self-concept and assertiveness amongst high school female students. Knowledge and Research in Applied Psychology, 19(1), 26–36.

Gilbert, P. (2009). Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 15(3), 199-208.

Gilbert, P. (2014). The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(1), 6–41.

Gilbert, P. (2015). The evolution and social dynamics of compassion. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9(6), 239–254.

Gilbert, P. (2019). Explorations into the nature and function of compassion. Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 108–114.

Gilbert, P. (2020). Compassion: From its evolution to a psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 3123.

Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Matos, M., & Rivis, A. (2011). Fears of compassion: Development of three self-report measures. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 84(3), 239–255.

Gilbert, P., Catarino, F., Duarte, C., Matos, M., Kolts, R., Stubbs, J., & Basran, J. (2017). The development of compassionate engagement and action scales for self and others. Journal of Compassionate Health Care, 4(1), 1–24.

Gilbert, P., Basran, J., MacArthur, M., & Kirby, J. N. (2019). Differences in the semantics of prosocial words: An exploration of compassion and kindness. Mindfulness, 10(11), 2259–2271.

Gilbert, P., & Mascaro, J. (2017). Compassion: Fears, blocks, and resistances: An evolutionary investigation. The Oxford Handbook of Compassion Science, 399–420.

Goetz, J. L., Keltner, D., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 351.

Gross, J. J. (2013). Emotion regulation: Taking stock and moving forward. Emotion, 13(3), 359.

Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26.

Grossenbacher, P. G., & Quaglia, J. T. (2017). Contemplative cognition: A more integrative framework for advancing mindfulness and meditation research. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1580-1593.

Helgeson, V. S., & Fritz, H. L. (1999). Unmitigated agency and unmitigated communion: Distinctions from agency and communion. Journal of Research in Personality, 33, 131–158.

Hunsinger, M., Livingston, R., & Isbell, L. (2013). The impact of loving-kindness meditation on affective learning and cognitive control. Mindfulness, 4(3), 275–280.

Jazaieri, H., Jinpa, G. T., McGonigal, K., Rosenberg, E. L., Finkelstein, J., Simon-Thomas, E., & Goldin, P. R. (2013). Enhancing compassion: A randomized controlled trial of a compassion cultivation training program. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(4), 1113–1126.

Jazaieri, H., McGonigal, K., Lee, I. A., Jinpa, T., Doty, J. R., Gross, J. J., & Goldin, P. R. (2018). Altering the trajectory of affect and affect regulation: The impact of compassion training. Mindfulness, 9(1), 283–293.

Jinpa, T. (2015). A fearless heart: How the courage to be compassionate can transform our lives. Hudson Street Press.

Kang, Y., Gray, J. R., & Dovidio, J. F. (2014). The nondiscriminating heart: Lovingkindness meditation training decreases implicit intergroup bias. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(3), 1306.

Kanov, J. M., Maitlis, S., Worline, M. C., Dutton, J. E., Frost, P. J., & Lilius, J. M. (2004). Compassion in organizational life. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(6), 808–827.

Khyentse, D. J. (2003). Introduction to the middle way: Chandrakirti’s Madhyamakavatara, with Commentary. Shambhala Publications.

Kirby, J. N., & Kirby, P. G. (2017). An evolutionary model to conceptualise masculinity and compassion in male teenagers: A unifying framework. Clinical Psychologist, 21(2), 74–89.

Kirby, J. N., Day, J., & Sagar, V. (2019). The ‘flow’ of compassion: A meta-analysis of the fears of compassion scales and psychological functioning. Clinical Psychology Review, 70, 26–39.

Klimecki, O. M., Leiberg, S., Lamm, C., & Singer, T. (2013). Functional neural plasticity and associated changes in positive affect after compassion training. Cerebral Cortex, 23(7), 1552–1561.

Ko, S. H., & Choi, Y. (2019). Compassion and job performance: Dual-paths through positive work-related identity, collective self esteem, and positive psychological capital. Sustainability, 11(23), 6766.

Kornfield, J. (2009). The wise heart: A guide to the universal teachings of Buddhist psychology. Bantam.

Lavelle, B. D. (2017). Compassion in context: Tracing the Buddhist roots of secular, compassion-based contemplative. In E. M. Seppala, E. SimonThomas, S. L. Brown, M. C. Wor line, C. D. Cameron, & J. R. Doty (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of compassion science (pp. 17–25). Oxford University Press.

Lee, Y., & Seomun, G. (2016). Development and validation of an instrument to measure nurses’compassion competence. Applied Nursing Research, 30, 76–82.

Leiberg, S., Klimecki, O., & Singer, T. (2011). Short-term compassion training increases prosocial behavior in a newly developed prosocial game. PLoS One, 6(3), e17798.

Lutz, A., Brefczynski-Lewis, J., Johnstone, T., & Davidson, R. J. (2008). Regulation of the neural circuitry of emotion by compassion meditation: Effects of meditative expertise. PLoS One, 3(3), e1897.

Makransky, J. (2016). Confronting the “sin” out of love for the “sinner”: Fierce compassion as a force for social change. Buddhist-Christian Studies, 36(1), 87–96.

Mascaro, J. S., Florian, M. P., Ash, M. J., Palmer, P. K., Frazier, T., Condon, P., & Raison, C. (2020). Ways of knowing compassion: How do we come to know, understand, and measure compassion when we see it? Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2467.

Matsunaga, D., & Matsunaga, A. (1974). The concept of upāya in Mahāyāna Buddhist philosophy. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 51–72.

McCall, C., Steinbeis, N., Ricard, M., & Singer, T. (2014). Compassion meditators show less anger, less punishment, and more compensation of victims in response to fairness violations. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 8, 424.

McRae, J. R. (2004). The Vimalakīrti Sutra: Translated from the Chinese (Taishō Volume 14, Number 475). The Sutra of Queen Śrīmālā of the Lion’s Roar and the Vimalakīrti Sutra, 57–181.

Mosewich, A. D., Ferguson, L. J., McHugh, T. L. F., & Kowalski, K. C. (2019). Enhancing capacity: Integrating self-compassion in sport. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 10(4), 235–243.

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250.

Neff, K. D. (2012). The science of self-compassion. In C. Germer & R. Siegel (Eds.), Compassion and wisdom in psychotherapy (pp. 79–92). Guilford Press.

Neff, K. (2018). Why women need fierce self-compassion. Greater Good Magazine (October), Greater Good Science Center University of California at Berkeley.

Paulhus, D. L., & Trapnell, P. D. (2008). Self-presentation of personality: An agency-communion framework. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality psychology: Theory and research (pp. 492–517) (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Peeters, G. (2005). Good and bad for self and other: Evaluative meaning processes in social cognition. Paper presented at the 14th general meeting of the European Association of Experimental Social Psychology, Wurzburg, Germany.

Quaglia, J. T., Cigrand, C., & Sallman, H. (2021). Caring for you, me, and us: The lived experience of compassion in counselors. Psychotherapy. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000412

Quaglia, J. T., Brown, K. W., Lindsay, E. K., Creswell, J. D., & Goodman, R. J. (2015). From conceptualization to operationalization of mindfulness. In K. W. Brown, J. D. Creswell, & R. M. Ryan (Eds.) Handbook of Mindfulness: Theory, research, and practice, 151–170.

Quaglia, J. T., Soisson, A., & Simmer-Brown, J. (2020). Compassion for self versus other: A critical review of compassion training research. Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–16.

Ramon, A. E., Guthrie, L., & Rochester, N. K. (2020). Role of masculinity in relationships between mindfulness, self-compassion, and well-being in military veterans. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 21(3), 357.

Reeder, G. D., & Brewer, M. B. (1979). A schematic model of dispositional attribution in interpersonal perception. Psychological Review, 86, 61–79.

Rosenberg, S., Nelson, C., & Vivekananthan, P. (1968). A multidimensional approach to the structure of personality impressions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, 283–294.

Rosenberg, E. L., Zanesco, A. P., King, B. G., Aichele, S. R., Jacobs, T. L., Bridwell, D. A., & Saron, C. D. (2015). Intensive meditation training influences emotional responses to suffering. Emotion, 15(6), 775.

Saucier, G. (2009). What are the most important dimensions of personality? Evidence from studies of descriptors in diverse languages. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(4), 620–637.

Schroeder, J. W. (2004). Skillful means: The heart of Buddhist compassion. Motilal Banarsidass Publications.

Seppälä, E. M., Simon-Thomas, E., Brown, S. L., Worline, M. C., Cameron, C. D., & Doty, J. R. (Eds.). (2017). The Oxford handbook of compassion science. Oxford University Press.

Simmer-Brown, J. (1992). Skillful means in the Tibetan Sutra and Tantra. Unpublished Draft.

Speed, B. C., Goldstein, B. L., & Goldfried, M. R. (2018). Assertiveness training: A forgotten evidence-based treatment. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 25(1), e12216.

Steindl, S. R., Yiu, R. X. Q., Baumann, T., & Matos, M. (2020). Comparing compassion across cultures: Similarities and differences among Australians and Singaporeans. Australian Psychologist, 55(3), 208–219.

Strauss, C., Taylor, B. L., Gu, J., Kuyken, W., Baer, R., Jones, F., & Cavanagh, K. (2016). What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures. Clinical Psychology Review, 47, 15–27.

Thurman, R. A. F. (2006). The holy teaching of Vimalakīrti: A Mahāyāna scripture. Pennsylvania State University Press.

Trungpa, C. (2008). Ocean of Dharma: The everyday wisdom of ChogyamTrungpa. Shambhala Publications.

Van Kleef, G. A., Oveis, C., Van Der Löwe, I., LuoKogan, A., Goetz, J., & Keltner, D. (2008). Power, distress, and compassion: Turning a blind eye to the suffering of others. Psychological Science, 19(12), 1315–1322.

Weng, H. Y., Fox, A. S., Shackman, A. J., Stodola, D. E., Caldwell, J. Z., Olson, M. C., & Davidson, R. J. (2013). Compassion training alters altruism and neural responses to suffering. Psychological Science, 24(7), 1171–1180.

Weng, H. Y., Fox, A. S., Hessenthaler, H. C., Stodola, D. E., & Davidson, R. J. (2015). The role of compassion in altruistic helping and punishment behavior. PLoS One, 10(12), e0143794.

Wiggins, J. S. (1979). A psychological taxonomy of trait-descriptive terms: The interpersonal domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 395–412.

Willis, J., & Todorov, A. (2006). First impressions: Making up your mind after a 100-ms exposure to a face. Psychological Science, 17(7), 592–598.

Wojciszke, B. (2005). Morality and competence in person and self-perception. European Review of Social Psychology, 16, 155–188.

Acknowledgements

I thank Dr. Judith Simmer-Brown and Dylan Leigh for their helpful feedback on this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Quaglia, J.T. One Compassion, Many Means: A Big Two Analysis of Compassionate Behavior. Mindfulness 14, 2430–2442 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01895-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01895-7