Abstract

Evidence is accumulating that mindfulness training is useful in reducing stress for health care workers and may increase the quality of their interactions with patients. To evaluate how health care workers experience mindfulness training, a review was conducted, synthesising published qualitative papers on the experiences of health care workers currently practising or those in clinical training who had attended mindfulness training. A systematic search yielded 14 relevant studies. Quality appraisal using the Critical Appraisal Skills programme tool identified that four studies were of a lower quality, and as they did not contribute uniquely to the analysis, they were omitted from the review. The synthesis describes health care workers’ experiences of overcoming challenges to practice in mindfulness training, such as shifting focus from caring for others to self-care, leading to an experiential understanding of mindfulness and a new relationship to experience. Perceived benefits of mindfulness training ranged from increased personal wellbeing and self-compassion to enhanced presence when relating to others, leading to enhanced compassion and a sense of shared humanity. Outcomes are discussed in terms of training focus and participant motivation, clinical and theoretical implications and avenues for further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A growing body of research reports positive outcomes from mindfulness training for various populations (Fjorback et al. 2011). Mindfulness is often defined as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally” (Kabat-Zinn 1994, p. 4). Mindfulness can be cultivated through formal practices which form the basis of two evidence-based interventions: mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR, Kabat-Zinn 2005) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT, Segal et al. 2002, 2013). MBSR was developed to reduce stress related to chronic illness and MBCT, which combines elements of MBSR with cognitive therapy, to reduce the likelihood of depressive relapse. Both are group-based interventions with eight weekly sessions and daily home practice, teaching core mindfulness practices such as a body scan, sitting meditations and mindful movement. Although differing in their original intentions and some aspects of course delivery, they have been used in comparable contexts with a range of populations (Chiesa and Serretti 2011; Praissman 2008). For the purposes of this review, mindfulness training is used to refer to MBSR, MBCT or adaptations to these interventions that contain the core mindfulness practices and underlying philosophies. For example, other interventions developed within the third wave of psychological therapies (e.g. acceptance and commitment therapy: Hayes et al. 1999; dialectical behaviour therapy: Linehan et al. 1999) include elements of mindfulness training as part of a wider syllabus but with less focus on formal practice of mindfulness meditation; therefore, they are not included in this definition.

Alongside studies exploring the efficacy of mindfulness training for various populations, mediation studies have sought to identify the active ingredients through which mindfulness training yields positive outcomes. For example, in MBCT increased mindfulness and self-compassion have been found to mediate the reductions in depressive symptoms and the likelihood of depressive relapse and decouple the relationship between cognitive reactivity and outcome (Kuyken et al. 2010). However, while mediation studies are useful in testing specific hypothesised relationships, other sources of evidence such as qualitative research are needed to provide a more holistic assessment.

Individual qualitative studies can provide a useful insight into the experiences of particular populations. Furthermore, they can also be systematically searched and synthesised. A number of approaches to qualitative synthesis exist (Thorne et al. 2004). For example, a meta-synthesis uses systematic search procedures to then compare and contrast studies to provide higher-level interpretations (e.g. Sandelowski et al. 1997). A qualitative meta-synthesis can complement quantitative findings of efficacy for an intervention by illuminating underlying processes and providing interpretations around the meaning ascribed to measured change. For example, a recent review synthesised patients’ experiences of mindfulness-based approaches from 14 original research articles (Malpass et al. 2011). The meta-synthesis produced a model of patients’ experiences of the therapeutic process that included participants opening up to experience then relating in a new way to experiences, their presenting difficulties and their sense of self. The model highlights participants’ shift in relation to their experience as an important mechanism of change, sometimes referred to as de-centering (Segal et al. 2013) or re-perceiving (Shapiro et al. 2006). These therapeutic processes were aided by group processes such as normalising early experiences of challenges in meditation and reducing perceived stigma and isolation.

Malpass and colleagues chose to “focus upon the patient experience” (Malpass et al. 2011, p. 2), and their review provides fresh insights and a working model of patients’ experiences. However, since health care workers are known to be vulnerable to stress and burnout (Maslach and Goldberg 1998), research has also addressed the utility of mindfulness training for health care workers and those in training. It is well established that under certain circumstances health care workers can experience significant levels of stress or burnout (e.g. Marine et al. 2006; Walsh and Walsh 2001). Various factors have been identified as contributing to burnout in health care workers, such as feeling ineffective and overwhelmed and seeing a need to “be selfless and put others’ needs first” (Maslach and Goldberg 1998, p. 63). Some factors such as experiencing organisational change and long working hours are also present in other workplaces. In addition, working in a physical or mental health care setting involves regularly encountering and working with individuals who are experiencing distress or illness, which can have a significant emotional impact (Michie and Williams 2003; Walsh and Walsh 2001). A deterioration in the mental and physical health of health care workers also has a detrimental impact on the care they can provide (Boorman 2009), making this an important issue to address for the wellbeing of health care workers and the patients with whom they work.

Recent quantitative reviews suggest that mindfulness training for this population may indeed reduce symptoms of stress, anxiety and depression, with other benefits reported such as increasing empathy, positive affect and self-compassion (Chiesa and Serretti 2009; Irving et al. 2009). Preliminary evidence also suggests that therapists with an ongoing mindfulness practice produce better patient outcomes (Grepmair et al. 2008). Bringing mindfulness into the therapeutic relationship may directly increase therapists’ ability to be present, to be aware and to show genuine curiosity and acceptance (Bruce et al. 2010; Hick et al. 2010). Similarly, there may be related interpersonal benefits for health care workers through increasing empathy in relationships with co-workers and patients.

In the last decade, several qualitative studies have explored health care workers’ experiences of mindfulness training, with intervention aims ranging from supporting staff and preventing burnout (Cohen-Katz et al. 2005a, b) to increasing the therapeutic presence of therapists in training (McCollum and Gehart 2010). These studies have a different focus to those exploring patient experience and have not yet been subject to review. Therefore, it was decided that a qualitative synthesis of health care workers’ experiences of mindfulness training would be a useful and timely addition to the evidence base, to bring together and make sense of this growing body of work. However, given the data constraints in many of the studies identified (i.e. a lack of richness of participant data), a meta-synthesis was not considered appropriate. Instead, this review aimed to conduct a systematic search but to use less formal procedures (i.e. not the seven-stage process outlined by Noblit and Hare 1988) to synthesise how health care workers perceive and experience mindfulness training as well as the perceived impact of mindfulness training on their wellbeing, clinical skills and relationships with patients.

Method

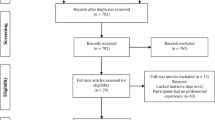

Literature Search

A literature search was conducted in March 2013 using databases and reference lists of related research papers and reviews (see Fig. 1). An initial search of the databases PsycINFO, Academic Search Complete, AMED, CINAHL and MEDLINE used variations on the terms “health care professional AND mindfulness AND qualitative” derived from database thesaurus suggestions, relevant titles already known to the first author and suggestions from a search specialist. The remaining papers were filtered manually by the first author using the criteria set out below, excluding studies that were clearly irrelevant through evaluation of the title and abstract and, where necessary, after sourcing original papers (for example, if an abstract was unclear whether qualitative methods were used in an evaluation). Comparative searches were also made using Web of Science and EMBASE, and a second phase of searching took place, hand searching reference lists of related papers and those identified for the review, screened using the same exclusion criteria. Finally, a search was conducted using the Mindfulness Research Guide (Black 2010), a comprehensive online database maintained through monthly literature searches and communications with authors and journals. While this search identified all papers dated 2010 onwards that were already sourced through other searches and some further papers that were excluded, no new articles were identified that met inclusion criteria for the review.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Included papers were peer-reviewed, reported a qualitative methodology and focused on the experience of health care workers or those in clinical training who had taken part in mindfulness training. Health care workers were defined as those in paid work in physical or mental health provision or taking part in clinical training within a health care profession. It is beyond the scope of this article to elaborate upon the differences in content and theoretical underpinnings between comprehensive mindfulness programmes and those therapies with a mindfulness component (see Chiesa and Malinowski 2011, for a detailed analysis). However, in order to synthesise a relatively homogenous set of articles, this review included studies that used MBSR, MBCT or training programmes that explicitly drew upon these approaches with the integration of core mindfulness practices such as sitting meditation, the body scan and mindful movement. Papers were not excluded on the basis of evaluating mindfulness training that was longer or shorter than the usual 8 weeks of MBCT or MBSR as adapting training length has been recognised as appropriate to meet the needs of participants and comparative effect sizes have been found for some shorter interventions (Carmody and Baer 2009). Qualitative studies were included that used a content-based approach such as thematic analysis or grounded theory and included some participant quotes; mixed-methods studies that met this criterion were also included. Where papers were identified referring to the same participant group, the decision was made not to include all of the papers to limit the possibility of one body of results disproportionately influencing the synthesis. For example, the published work of Gockel and colleagues included a mixed-methods study with a qualitative component (Gockel et al. 2012) and a more comprehensive qualitative study (Gockel et al. 2013), and so the decision was made to include only the latter in this review. Moreover, data by Christopher and colleagues were represented in four qualitative studies (Christopher et al. 2006, 2011; Newsome et al. 2006; Schure et al. 2008). The paper judged to demonstrate the most comprehensive qualitative analysis was included (Schure et al. 2008) as well as a second paper that reported additional data resulting from analysis of participants’ long-term perceptions of the effect of the mindfulness training (Christopher et al. 2011).

Papers Identified for Inclusion

Fourteen papers were identified for inclusion in the synthesis (see Table 1) reporting the experiences of 254 participants. Participants included both trainees and qualified professionals in social work, counselling, nursing and clinical psychology as well as trainee occupational and family therapists and qualified physicians. Four papers did not report gender; across the other ten papers, 84 % of 181 participants were female. The purpose of training in most studies was to reduce stress or increase wellbeing and to impact on the interpersonal skills of the participants, although some papers focused on one element or the other in their intervention and/or reporting. The first three papers published used MBSR, and only one subsequent paper explored experiences of the MBCT protocol. Instead, most papers described interventions that used the core mindfulness practices alongside other didactic or practical content related to the intentions of the study, for example, exploring the use of mindfulness for clinicians through role-playing therapeutic interactions (Gockel et al. 2013).

The length of the initial mindfulness training ranged from 4 to 15 weeks (eight studies kept an 8-week format), with one study including ten individual monthly follow-up sessions after an 8-week course (Beckman et al. 2012). Most studies that deviated from the 8-week format used a higher number of shorter sessions to integrate the course content within an existing syllabus. Five studies did not report the level of facilitator experience, and one study used self-facilitation where participants read meditation scripts themselves (Moore 2008). The remaining facilitators had a minimum of 2 years’ mindfulness experience and specific supervision or training in MBSR or MBCT, with four studies reporting over 15 years of facilitator experience (Christopher et al. 2011; McCollum and Gehart 2010; McGarrigle and Walsh 2011; Schure et al. 2008).

Most studies collected data during or just after the course, with several collecting data up to 6 months afterwards and only three looking at long-term data (10–16 months, 18 months and 2 to 6 years after training). Results based on data from the time of course completion did not appear to differ significantly based on length of training; however, the studies looking at long-term data which delivered more comprehensive mindfulness training reported more ongoing benefits.

Eight studies also reported quantitative findings or had a complementary research paper detailing quantitative findings with the same populations. Although many had small sample sizes and reported other results that showed non-significant trends towards related benefits, they found statistically significant reductions in scores on self-report measures of perceived stress (Beddoe and Murphy 2004; McGarrigle and Walsh 2011), anxiety (De Zoysa et al. 2012b; Ruths et al. 2012), psychological or health-related symptoms (Young et al. 2001) or burnout (Cohen-Katz et al. 2005b; Krasner et al. 2009) and improved mood, empathy (Krasner et al. 2009), and psychological wellbeing (De Zoysa et al. 2012b; Ruths et al. 2012). One study also reported an increase in self-reported self-efficacy in counselling which has been linked to clinical skills development (Gockel et al. 2012).

Quality Appraisal

The quality of studies was rated using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2010) which is used to assess aspects such as the aims, methodology, rigour of analysis and value of results. Based on the approach of Dixon-Woods et al. (2007), rather than giving papers a numerical score, papers were identified by the first author as either KP (a key paper that is conceptually rich and could potentially make an important contribution), SAT (a satisfactory paper) or FF (a paper that is fatally flawed methodologically). Ten papers were rated KP, three as SAT and one FF (Birnbaum 2008); the most common issues were not reporting methods of data analysis or reflecting on the impact of the researcher.

The issue of whether studies should be excluded from a review based on the quality of the methodology used or the way a study is reported is contentious (Carroll et al. 2012; Sandelowski et al. 1997). It has been shown that disagreements between researchers about whether a paper should be included in a review are common, regardless of whether or not structured appraisal tools are used (Dixon-Woods et al. 2007). Therefore, the decision was taken to conduct the analysis with papers of all qualities and to determine whether those rated SAT or FF made differing contributions to the synthesis. This allows the opportunity for any unique findings in studies of a lower quality to be critically examined.

Analysis

The analysis process, conducted by the first author, began with reading and re-reading the papers and the creation of brief summaries of main concepts and conclusions. Themes and concepts from each paper were collated into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet using the original language of the study authors, as well as contextual factors such as study aims, content, participant motivation and goals and time of data collection relative to the intervention. Sorting the themes and concepts allowed for the creation of over-arching categories. A brief narrative summary was then written that captured the essence of each of the categories as they appeared across the review papers. None of the papers rated as SAT or FF contributed uniquely to a narrative summary, and so the decision was made not to draw from them further as the analysis progressed. The narrative summaries were then used to create a coherent narrative reflecting participants’ experiences of mindfulness training and subsequent benefits. Where experiences differed between or within papers, moving between the narrative summaries and the original papers allowed for interpretations to be made regarding possible sources of variation.

Results

Concepts from the papers were grouped into 61 categories which were then refined by writing narrative summaries and amalgamating complementary categories, resulting in the 33 categories listed in Table 2. Although the papers reported the experiences of a number of different professions as well as health care workers in training, similar constructs were identified across the papers without a clear distinction, and so they are reported together. The constructs identified were organised into themes to make sense of participants’ experiences: (1) experiencing and overcoming challenges to mindfulness practice and (2) changing relationship to experience in (a) personal and (b) interpersonal domains. Each of these areas are considered below followed by a discussion of implications for theory, practice and future research.

-

1.

Health care workers experiencing and overcoming challenges to mindfulness practice

A significant aspect of health care workers’ experience in mindfulness training was encountering and responding to challenges in formal mindfulness practice. Some participants described feeling guilty about looking after themselves, making a connection between this feeling and their identities as health care workers. For example, one participant said, “I’m having trouble focusing on myself and not others’ problems. It’s the nurse in me.” (Cohen-Katz et al. 2005a). This was experienced as a barrier to formal practice and using self-care more generally. Health care workers said that they treated themselves more positively as the course went on. For example, Cohen-Katz et al. (2005a) reported, “a large increase in comments related to self-acceptance, self-awareness and self care” from week five onwards. This provides evidence to suggest that health care workers were able to incorporate the value of self-care into their identity.

Just as patients attending mindfulness training often recognise that they are not alone in facing their illness or mental health issues (Malpass et al. 2011), a key factor in changing health care workers’ attitudes was being able to witness and understand that they were not alone in experiencing difficulties: “the most meaningful part was being with other physicians, sharing and discussing some of our experiences, and being able to have the immediate understanding of peers with respect to the struggles that we all have” (Beckman et al. 2012). This benefit could be considered non-specific to mindfulness training as, in theory, attending any group and sharing experiences may have resulted in similar realisations. However, there were other benefits that appeared to be more specific to mindfulness training such as cultivating self-compassion: “To hear somebody in my professional sphere say ‘have compassion towards yourself’… To hear it in this context, it’s a very powerful facilitator of the message” (Irving et al. 2012).

Other challenges experienced were comparable to patients’ experience ranging from practical issues, such as finding time to practice at home or work, to psychological issues such as restlessness, sleepiness or intense emotions during meditation practice. The degree to which participants were able to navigate past these barriers varied between and within studies. However, the majority of studies suggested that most participants had done so successfully. For example, Cohen-Katz et al. (2005a) used weekly journal entries during the course as a source of data and reported that “comments about restlessness peaked in week two however, and declined thereafter” and similarly that comments about physical challenges in practice stopped after week 5.

Participants’ motivations are known to affect the way in which they engage with training and subsequent outcomes (Noe and Schmitt 1986). Most studies reported that participants had elected to attend the mindfulness training for stress management or as part of clinical skills development. Only two studies reported that participants had no choice about attending mindfulness training as it was incorporated into their clinical training (McCollum and Gehart 2010; Gockel et al. 2013); however, this did not appear to reduce their engagement or subsequent benefits. Participants in De Zoysa et al.’s study (De Zoysa et al. 2012a) were recruited from a group who attended training “not only for their own well-being, but also to learn about a new therapy likely to be of potential use with their clients” (Ruths et al. 2012). Quotes from participants suggested that perhaps they had not progressed beyond initial challenges and thus may not have engaged with mindfulness at a deeper level:

All the time I’ve got that secondary conversation going on ‘what am I getting from this, what am I achieving at the end of this?’ and I think that that’s what [the barrier to regular practice] is. (De Zoysa et al. 2012a)

Indeed, it may be that participants focused on learning techniques they could use with clients were less motivated to navigate around barriers than those interested primarily in self-care. Shapiro and colleagues suggested that “the effects of practice on psychological outcomes may only appear when some critical threshold of practice time has been met” (Shapiro et al. 2007) yet acknowledged that quality of practice time is potentially as relevant as quantity. In some instances, health care workers simply may not have practiced enough to develop further in their understanding and integration of mindfulness. Yet even if they continue to practice for the duration of the course and beyond (as results of the quantitative study that complements De Zoysa et al.’s paper suggest: Ruths et al. 2012), if barriers are still in place, the quality of practice and subsequent benefits may be limited. Therefore, an important factor in mindfulness training for health care workers may be addressing initial motivation and communicating the need to develop a personal understanding of mindfulness, in order to shift the focus away from helping others.

Participants in the longer-term studies by Christopher et al. (2011) and Beckman et al. (2012) appeared to have continued to engage with and use mindfulness. The mindfulness training they had was more in depth, with greater contact time over longer periods and highly experienced facilitators, and so these factors may be important in establishing a “deep, rather than surface, understanding” (Barnett and Ceci 2002, p. 616) associated with greater transfer of learning from training into other contexts. Once initial challenges have been passed, there may also be a requirement for some form of ongoing support to maintain practice. Indeed, the study by Beckman et al. (2012) demonstrates that having monthly drop-in sessions (even though attendance was variable) may have allowed participants to keep in touch with what they had learned and to continue using mindfulness. Authors of most studies suggested that ongoing practice should be supported through organisational support, providing access to further group sessions, integrating mindfulness into clinical supervision and considering general reminders. Again, this relates to the recognition in the training literature that organisational support is an important part of facilitating the transfer of learning from training to the workplace (Noe and Schmitt 1986) as well as an expectation that participants will put what has been learnt into practice (Kraiger and Culbertson 2013).

-

2.

Beyond the barriers: health care workers changing their relationship to experience

Health care workers’ accounts support the theory that through mindfulness training participants change their relationship to experience, dis-identifying with the content of the experience (such as thoughts), and have more clarity to observe what is there (Segal et al. 2013). Whereas studies of patients’ journeys often illustrate the personal origins of changing relationships to experience, studies of health care workers’ have explored shifts in both personal and interpersonal domains.

-

(a)

Benefits for health care workers in relating mindfully towards individual experiences: “freeing, empowering and liberating”

Health care workers experienced shifts in the way they coped with emotions and how they related to themselves which, for some participants, led to improvements in self-care, confidence, decision making and productivity. Some studies also reported increases in physical wellbeing and ability to cope with pain as well as providing an opportunity to reflect on spirituality. Although all studies contributed to the data on personal benefits of mindfulness training, the extent to which participants were reported to have benefitted in this domain varied both within and between papers. This issue will be returned to after discussion of interpersonal benefits as it is relevant to both domains.

Through attending to their experiences with an accepting attitude, health care workers were able to gain insight into their intrapersonal processes, step back from them and gain more composure to respond rather than react. Participants felt more able to cope with difficult thoughts and “to an extent note and let go of arising emotions” (Schure et al. 2008) as well as opening to and appreciating pleasant experiences. Health care workers felt increasingly comfortable with self-acceptance and self-care. This quote from a counsellor in Christopher’s long-term follow-up study shows how these changes have the potential to have lasting and profound effects:

I have more compassion for myself… it feels good. I’m prone to recover from down days faster… I realized, you know, I have a choice in how I’m going to treat myself… it has been freeing, empowering, and liberating. (Christopher et al. 2011)

Being able to be more aware and attend to emotions also had direct implications in terms of engaging with work: for example, one occupational therapy student said, “when I was struggling with completing an essay last week… I was aware of my mind wandering off and finding excuses… I was able to accept the situation and then focus more readily on the task in hand” (Stew 2011). Similarly, some qualified nurses reported being able to accept and prioritise their workload (Cohen-Katz et al. 2005a).

A further outcome for health care workers involved their confidence in decision making. For example, one participant said, “I feel more grounded and I’m trusting my own perceptions more.... feel more confidence in my decision making” (Schure et al. 2008), while another reflected on self-acceptance, recognising one’s limits and letting go of getting everything right: “It allows me to reach out and consult, and be okay with not having all the answers… what’s going to make me more competent is if I recognize when I’m feeling stuck” (Christopher et al. 2011).

Benefits were also reported in terms of physical wellbeing. Just as participants were approaching emotions in a different way, some reported changing their relationship to physical pain. Many participants also reported that their physical health had improved in terms of reducing symptoms of illness and improving sleep, eating habits, flexibility and strength. This highlights that mindfulness training can produce holistic changes that are not always measured in quantitative studies if they are not the primary target of the intervention, yet in many studies, mindfulness training is targeted at physical health (Carmody et al. 2009).

Finally, some participants reported that they felt mindfulness training integrated well with their religious or spiritual beliefs. For example, one participant said, “By adding the element of prayer to my meditation it was easier to connect with my true self… I entered the clinic with a greater sense of patience for my progress and compassion for my struggles” (McCollum and Gehart 2010). Although some brief references were made to participants’ initial scepticism about the religious connotations of meditation or being told by others that it might conflict with existing beliefs, the majority of references described participants having positive experiences when reflecting on their spirituality in relation to mindfulness training.

-

(b)

Benefits for health care workers in relating mindfully with others: the power of empathy and “genuine compassion”

Participants benefitted interpersonally through becoming more aware when relating to others (of themselves, the other person and the interaction) and being able to choose how to act. For example, many participants spoke about using mindfulness to ground themselves or gain focus prior to seeing patients or clients, “the mindfulness practice has helped me to center myself between each session… it has become increasingly important for me to leave each client in their time slot and not take them with me into the next session” (McCollum and Gehart 2010). Health care workers also learnt how to bring mindfulness into interactions with patients or clients. For example, one participant spoke about the impact of sitting with a client when they were highly agitated.

My ability to draw upon my own peaceful sense inside helped me not only maintain control in the session, but impart something to the client that words alone could not have communicated. (McCollum and Gehart 2010)

This was part of a conceptual shift whereby health care workers were exploring the value of being with patients and feeling “less pressure to fix” (Schure et al. 2008).

I always felt that… my patients were coming to me to have something fixed, and that my expectation of myself was that I was supposed to do something… And I think I came to realize… just being there in the present moment and with their experience is, is very powerful. (Irving et al. 2012)

Many of the studies explored whether mindfulness training cultivated empathy in health care workers. McCollum and Gehart reported that participants experienced increased empathy for clients through a sense of “shared humanity” (2010, p. 351). Participants’ accounts suggest that this may be as a result of understanding and accepting themselves and their own experiences of suffering:

I have been noticing my capacity for empathy has increased as I have been engaged in this class. I have a notion this is the result of becoming aware when I am being judgmental of others or myself. I have increased my compassion, which in turn, has given me an increased capacity to have more genuine compassion for others. (Schure et al. 2008)

Finally, through their own journey with mindfulness, health care workers were able to feel more hopeful about the potential for therapeutic change: “We all have so much more power and ability to heal ourselves and take care of ourselves than we even know. So, I think that instilled some hope in me at a time when I really needed that” (Christopher et al. 2011).

Where participants were confident in teaching mindfulness, they were careful about when to do so; however, some may not have had sufficient grounding in mindfulness practice which resulted in some confusion with clients, “I think [the client] just got confused between things like whether he should be suppressing thoughts or not suppressing them or being mindful towards them or distract himself, it all became a bit muddled really” (De Zoysa et al. 2012a). The results support the reasoning that in order to teach mindfulness successfully, a strong foundation in personal practice is needed as well as specific skills in teaching mindfulness (McCown et al. 2010; Segal et al. 2013).

-

(a)

Making Sense of Variations

It is important to note that the range of personal and interpersonal benefits was not experienced by all participants and there were variations both within and between papers. In contemporary conceptual models of the transfer of learning from training, individual differences are expected in what participants learn based on their interpretations of and engagement with the training (Kraiger and Culbertson 2013). Indeed, many study authors referred to a distinction between participants who engaged with mindfulness as a set of tools to help with self-care or to apply to improve their work and participants who engaged with mindfulness as a way of being. The likelihood of a more superficial engagement with mindfulness may increase based on the initial intentions of participants (as was discussed earlier) or the way in which a course is taught. For example, Beddoe and Murphy suggested that there was an untapped potential for interpersonal benefits from their training because “the intervention content emphasised self-care but did not directly encourage empathy for others” (Beddoe and Murphy 2004). Similarly, Gockel et al. posited in an earlier paper that focusing on using mindfulness in clinical practice may have benefitted clinical learning “but detracted from the overall impact of the training on their well-being and their development of mindfulness itself by introducing a competing and, in fact, a superordinate focus for the course” (Gockel et al. 2012). Indeed, some participants did appear to gain insight into the use of mindfulness interpersonally rather than basing their understanding on intrapersonal experience.

I was sort of ambivalent about the mindfulness activities in the beginning. And towards the end, I just sort of really realized how much those activities helped me to be present and really helped to facilitate the role-plays that we did in the class (Gockel et al. 2013).

The contrasting results of these two papers suggest that mindfulness can be developed in either the intrapersonal context (in terms of self-care) or the interpersonal context (as a way of interacting with patients or clients) without necessarily overlapping. Nevertheless, the comments of both authors suggest that neglecting either the intrapersonal or interpersonal applicability of mindfulness reduces the possible benefits of a more holistic and comprehensive understanding.

Discussion

Through engaging in formal mindfulness practice and overcoming challenges to practice, health care workers were sometimes able to increase their level of awareness and relate to themselves and patients in a more accepting and compassionate way. At a time when compassion is high on political agendas in the UK with recommendations for more attention to compassionate care in the selection, training and evaluation of health care workers (Francis 2013), this review highlights several relevant points. Firstly, health care workers participating in mindfulness training have been shown to develop a greater sense of “shared humanity” (McCollum and Gehart 2010) with patients through coming to terms with their own vulnerabilities, accepting themselves and seeing how their experience of suffering related to that of patients (Christopher et al. 2011). As an experiential training, mindfulness training provides the opportunity for health care workers to understand shared humanity both conceptually and through developing a greater meta-cognitive awareness, exploring and accepting themselves (Bruce et al. 2010). Secondly, health care workers felt an increasing capacity to be present in a compassionate way with patients through attending to their own self-care needs. As one participant said, “When you take care of yourself, you just have more to give. I’m more focused on my patients now” (Cohen-Katz et al. 2005a, b, p. 84). This attitudinal shift away from the need to “be selfless and put others’ needs first” (Maslach and Goldberg 1998, p. 63) may be a significant factor in reducing health care workers’ vulnerability to burnout as well as an indirect yet effective way of increasing compassionate care across health care services. Further evidence for the reduced risk of burnout was identified through health care workers feeling more able to manage strong emotions and experience distress without needing to “fix” it.

Factors to Consider in the Implementation of Mindfulness Training for Health Care Workers

The degree to which health care workers benefit from mindfulness training as individuals and interpersonally may relate to their initial intentions, whether the mindfulness training has specific or more general aims, the amount and quality of practice and whether there is support for ongoing engagement with mindfulness over time. Moreover, in the studies reviewed, participants who were using mindfulness as a set of tools primarily applied it in the way it was taught to them whereas those who adopted mindfulness as a way of being were more likely to be able to use mindfulness across contexts. This resonates with the findings in wider literature pertaining to the transfer of learning from training, which suggests that it is common for learning to be restricted to use in the way in which it was taught, yet participants who gain a deeper understanding may be able to generalise their learning (Barnett and Ceci 2002).

Therefore, facilitators should consider carefully what the aims of the mindfulness training are (such as self-care or interpersonal development) and whether the content and delivery reflect these aims, as well as monitoring the motivations of participants. Care should be taken to adequately address challenges to formal practice and provide an intervention with enough practice time to give participants the opportunity to develop a deeper understanding of mindfulness. Encouraging participants to explore mindfulness on a personal level (as opposed to simply looking for skills to apply) may increase the likelihood of this occurring. Specific training such as the use of role play may be an important tool in increasing understanding about how mindfulness can be used interpersonally as well as giving health care workers the opportunity to practice and build up confidence in using mindfulness in a non-clinical environment. Actively supporting participants to continue to practice over time may be an important part of maintaining benefits or continuing to develop understanding.

Although two studies in this review reported positive findings having incorporated mindfulness training into clinical training without participants opting in, no studies examined the experience of health care workers conscripted to mindfulness training. Health care providers may consider mindfulness training to be a useful remedy to stress in the workplace; however, it is unclear how making the training mandatory might change both the experience and perceived outcomes. If indeed this is an option considered, further research is needed to explore to what extent conscription impacts on the experience of mindfulness training.

Implications for Theory

Shapiro et al. (2006) posit that mindfulness is comprised of intention, attention and attitude. Intention refers to an individual’s reasons for cultivating mindfulness, which may vary from person to person and over time, and this review has considered some of the ways in which intention may impact upon outcomes. Attention in mindfulness refers to moment-to-moment awareness of experiences, both internal and external, and this review supports the theory that cultivating attention is as an essential step towards experiencing perceived benefits. Attitude refers to “the heart aspects of practice” (Bruce et al. 2010, p. 84), bringing qualities such as curiosity, openness, acceptance and love (Siegel 2007) to the present moment experience. Health care workers’ experiences reaffirm that it is the shift towards this attitude in relating to experience, coupled with de-centring or re-perceiving (Shapiro et al. 2006), that underpins both intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits (Bruce et al. 2010). Indeed, initial empirical evidence suggests that it is the combination of increased levels of mindfulness and the ability to re-perceive that mediate outcomes of mindfulness training (Carmody et al. 2009).

The results of this review suggest, both in the accounts of health care workers and the interpretations of study authors, that while mindfulness can be cultivated in either the personal or interpersonal domain, there are further benefits to be gained through the knowledge and application of relating mindfully to both self and others. For example, using mindfulness to relate to patients differently may enhance clinical skills (Gockel et al. 2013), yet it is necessary to relate to both self and other with compassion in order to experience a sense of shared humanity (Christopher et al. 2011). Although the way of relating is essentially the same whether focused on self or other, and individuals can begin to explore crossing into the opposite domain themselves, if there are barriers to relating mindfully to self or other, then providing training in both domains may be most beneficial. While there is a focus in the UK on developing compassion in health services, especially as a result of well-publicised failures of NHS staff to provide high-quality care (e.g. Francis 2013), the expected course of action may be to try and teach health care workers to care more for their patients. However, the evidence in this review suggests that rather than needing to teach compassion for others, supporting health care workers to engage in self-compassion and self-care can act as a stronger foundation on which to maintain an existing ability to care for others.

Strengths and Limitations

This review provides evidence to suggest that mindfulness training can result in positive outcomes for a range of health care disciplines. It is important to note that not all participants reported all of the outcomes discussed. Instead, the review demonstrates the range of experiences health care workers have had with mindfulness training and discusses the factors relevant to how they may have engaged differently with the training process.

It could be considered a limitation that more strict criteria were not applied when selecting studies to include as this then limited the application of more interpretative synthesis methods (e.g. Noblit and Hare 1988). It is recommended that, when further studies are carried out with improved methodology, a further synthesis is carried out using more formal procedures. Involving more researchers in the process may also support a more comprehensive analysis.

Future Research

This review highlights some of the complexity regarding how health care workers engage with mindfulness training and the range of potential benefits they might report. For example, future research in this area, both quantitative and qualitative, could consider what the aims of a given intervention are and how this is communicated through the actions of the facilitator and the course content, how best to capture participants’ motivations, how this might impact upon their experience and engagement and how best to support the process of overcoming challenges to practice. Relatively few papers examined the effects of training over time, and so further research with a longitudinal component may be useful to better understand what increases the likelihood of maintaining reported benefits. Finally, whilst the majority of research has focused on if and how mindfulness training is beneficial to health care workers, as the evidence for benefits grows, there is a need to further compare the outcomes and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness training with other training programmes (e.g. relaxation training, Jain et al. 2007).

Conclusions

Through engaging in formal mindfulness practice and overcoming challenges to practice, health care workers were sometimes able to increase their level of awareness and relate to themselves and others in a more accepting and compassionate way. The degree to which health care workers benefitted from mindfulness training varied based on factors such as their initial intentions, whether they moved past initial challenges to practice and whether they engaged with mindfulness at a deeper level. This review demonstrates the range of potential benefits of mindfulness training for health care workers and those in training, to reduce stress and increase wellbeing, as well as to further develop and enhance the way they relate to patients or clients. Some evidence also suggested that health care workers were more confident in decision making as well as recognising the limits of their competency and asking for help. Therefore, mindfulness training is a promising option for supporting health care workers and enhancing the care for those with whom they work.

References

Barnett, S. M., & Ceci, S. J. (2002). When and where do we apply what we learn?: a taxonomy for far transfer. Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 612–637. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.612.

Beckman, H. B., Wendland, M., Mooney, C., Krasner, M. S., Quill, T. E., Suchman, A. L., & Epstein, R. M. (2012). The impact of a program in mindful communication on primary care physicians. Academic Medicine: Journal Of The Association Of American Medical Colleges, 87(6), 815–819. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318253d3b2.

Beddoe, A. E., & Murphy, S. O. (2004). Does mindfulness decrease stress and foster empathy among nursing students? Journal of Nursing Education, 43(7), 305–312.

Birnbaum, L. (2008). The use of mindfulness training to create an ‘accompanying place’ for social work students. Social Work Education, 27(8), 837–852. doi:10.1080/02615470701538330.

Black, D. (2010). Mindfulness research guide: a new paradigm for managing empirical health information. Mindfulness, 1(3), 174–176. doi:10.1007/s12671-010-0019-0.

Boorman, S. (2009). NHS health and well-being review: interim report. (296741). Retrieved from http://www.nhshealthandwellbeing.org/InterimReport.html.

Bruce, N. G., Manber, R., Shapiro, S. L., & Constantino, M. J. (2010). Psychotherapist mindfulness and the psychotherapy process. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 47(1), 83–97. doi:10.1037/a0018842.

Carmody, J., & Baer, R. A. (2009). How long does a mindfulness-based stress reduction program need to be? A review of class contact hours and effect sizes for psychological distress. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(6), 627–638. doi:10.1002/jclp.2055.

Carmody, J., Baer, R. A., Lykins E, L. B., & Olendzki, N. (2009). An empirical study of the mechanisms of mindfulness in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(6), 613–626. doi:10.1002/jclp.20579.

Carroll, C., Booth, A., & Lloyd-Jones, M. (2012). Should we exclude inadequately reported studies from qualitative systematic reviews? An evaluation of sensitivity analyses in two case study reviews. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1425–1434. doi:10.1177/1049732312452937.

Chiesa, A., & Malinowski, P. (2011). Mindfulness-based approaches: are they all the same? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(4), 404–424. doi:10.1002/jclp.20776.

Chiesa, A., & Serretti, A. (2009). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: a review and meta-analysis. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine, 15(5), 593–600. doi:10.1089/acm.2008.0495.

Chiesa, A., & Serretti, A. (2011). Mindfulness based cognitive therapy for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 187(3), 441–453. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.011.

Christopher, J. C., Christopher, S. E., Dunnagan, T., & Schure, M. (2006). Teaching self-care through mindfulness practices: the application of yoga, meditation, and qigong to counselor training. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 46(4), 494–509. doi:10.1177/0022167806290215.

Christopher, J. C., Chrisman, J. A., Trotter-Mathison, M. J., Schure, M. B., Dahlen, P., & Christopher, S. B. (2011). Perceptions of the long-term influence of mindfulness training on counselors and psychotherapists: a qualitative inquiry. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 51(3), 318–349. doi:10.1177/0022167810381471.

Cohen-Katz, J., Wiley, S., Capuano, T., Baker, D. M., Deitrick, L., & Shapiro, S. L. (2005a). The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on nurse stress and burnout: a qualitative and quantitative study, part III. Holistic Nursing Practice, 19(2), 78–86.

Cohen-Katz, J., Wiley, S. D., Capuano, T., Baker, D. M., & Shapiro, S. L. (2005b). The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on nurse stress and burnout, part II: a quantitative and qualitative study. Holistic Nursing Practice, 19(1), 26–35.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2010). Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: making sense of evidence about clinical effectiveness. From http://www.casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/CASP_Qualitative_Appraisal_Checklist_14oct10.pdf.

De Zoysa, N., Ruths, F. A., Walsh, J., & Hutton, J. (2012a). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for mental health professionals: a long-term qualitative follow-up study. Mindfulness. doi:10.1007/s12671-012-0141-2.

De Zoysa, N., Ruths, F. A., Walsh, J., & Hutton, J. (2012b). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for mental health professionals: a long-term quantitative follow-up study. Mindfulness. doi:10.1007/s12671-012-0176-4.

Dixon-Woods, M., Sutton, A., Shaw, R., Miller, T., Smith, J., Young, B., & Jones, D. (2007). Appraising qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: a quantitative and qualitative comparison of three methods. Journal Of Health Services Research & Policy, 12(1), 42–47.

Fjorback, L. O., Arendt, M., Ørnbøl, E., Fink, P., & Walach, H. (2011). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy—a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124, 102–119. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01704.x.

Francis, R. (2013). Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust public inquiry: executive summary. London: The Stationary Office.

Gockel, A., Burton, D., James, S., & Bryer, E. (2012). Introducing mindfulness as a self-care and clinical training strategy for beginning social work students. Mindfulness, 1–11. doi:10.1007/s12671-012-0134-1.

Gockel, A., Cain, T., Malove, S., & James, S. (2013). Mindfulness as clinical training: student perspectives on the utility of mindfulness training in fostering clinical intervention skills. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work, 32(1), 36–59. doi:10.1080/15426432.2013.749146.

Grepmair, L., Mitterlehner, F., & Nickel, M. (2008). Promotion of mindfulness in psychotherapists in training. Psychiatry Research, 158(2). doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2007.11.007.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: an experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford Press.

Hick, S. F., Bien, T., & Segal, Z. V. (2010). Mindfulness and the therapeutic relationship. New York: Guilford Publications.

Irving, J., Dobkin, P. L., & Park, J. (2009). Cultivating mindfulness in health care professionals: a review of empirical studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Complementary Therapies In Clinical Practice, 15(2), 61–66. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2009.01.002.

Irving, J., Park-Saltzman, J., Fitzpatrick, M., Dobkin, P., Chen, A., & Hutchinson, T. (2012). Experiences of health care professionals enrolled in mindfulness-based medical practice: a grounded theory model. Mindfulness, 1–12. doi:10.1007/s12671-012-0147-9.

Jain, S., Shapiro, S. L., Swanick, S., Roesch, S. C., Mills, P. J., Bell, I., & Schwartz, G. E. R. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 33(1), 11–21. doi:10.1207/s15324796abm3301_2.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York: Hyperion.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2005). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness (15 th anniversary edn.). New York: Bantam Dell.

Kraiger, K., & Culbertson, S. S. (2013). Understanding and facilitating learning: advancements in training and development. In N. W. Schmitt, S. Highhouse, & I. B. Weiner (Eds.), Handbook of psychology, Vol. 12: Industrial and organizational psychology (2nd ed., pp. 244–261). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Krasner, M. S., Epstein, R. M., Beckman, H., Suchman, A. L., Chapman, B., Mooney, C. J., & Quill, T. E. (2009). Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association, 302(12), 1284–1293. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1384.

Kuyken, W., Watkins, E., Holden, E., White, K., Taylor, R. S., Byford, S., & Dalgleish, T. (2010). How does mindfulness-based cognitive therapy work? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(11), 1105–1112. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.08.003.

Linehan, M. M., Kanter, J. W., & Comtois, K. A. (1999). Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder: efficacy, specificity, and cost effectiveness. In D. S. Janowsky (Ed.), Psychotherapy indications and outcomes (pp. 93–118). Washington: American Psychiatric Association.

Malpass, A., Carel, H., Ridd, M., Shaw, A., Kessler, D., Sharp, D., . . . Wallond, J. (2011). Transforming the perceptual situation: a meta-ethnography of qualitative work reporting patients’ experiences of mindfulness-based approaches. Mindfulness, 1–16. doi:10.1007/s12671-011-0081-2.

Marine, A., Ruotsalainen, J., Serra, C., & Verbeek, J. (2006). Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4), doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002892.pub2.

Maslach, C., & Goldberg, J. (1998). Prevention of burnout: new perspectives. Applied & Preventive Psychology, 7(1), 63–74. doi:10.1016/S0962-1849(98)80022-X.

McCollum, E. E., & Gehart, D. R. (2010). Using mindfulness meditation to teach beginning therapists therapeutic presence: a qualitative study. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 36(3), 347–360. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2010.00214.x.

McCown, D., Reibel, D. C., & Micozzi, M. S. (2010). Teaching mindfulness: a practical guide for clinicians and educators. New York: Springer.

McGarrigle, T., & Walsh, C. A. (2011). Mindfulness, self-care, and wellness in social work: effects of contemplative training. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 30(3), 212–233.

Michie, S., & Williams, S. (2003). Reducing work related psychological ill health and sickness absence: a systematic literature review. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60(1), 3–9. doi:10.1136/oem.60.1.3.

Moore, P. (2008). Introducing mindfulness to clinical psychologists in training: an experiential course of brief exercises. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 15(4), 331–337. doi:10.1007/s10880-008-9134-7.

Newsome, S., Christopher, J. C., Dahlen, P., & Christopher, S. (2006). Teaching counselors self-care through mindfulness practices. Teachers College Record, 108(9), 1881–1900. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00766.x.

Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. London: Sage.

Noe, R. A., & Schmitt, N. (1986). The influence of trainee attitudes on training effectiveness: test of a model. Personnel Psychology, 39(3), 497–523.

Praissman, S. (2008). Mindfulness-based stress reduction: a literature review and clinician’s guide. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 20(4), 212–216. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00306.x.

Ruths, F., de Zoysa, N., Frearson, S., Hutton, J., Williams, J., & Walsh, J. (2012). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for mental health professionals—a pilot study. Mindfulness, 1-7. doi:10.1007/s12671-012-0127-0.

Sandelowski, M., Docherty, S., & Emden, C. (1997). Qualitative metasynthesis: issues and techniques. Research in Nursing & Health, 20(4), 365–371. doi:10.1002/(sici)1098-240x.

Schure, M. B., Christopher, J., & Christopher, S. (2008). Mind-body medicine and the art of self-care: teaching mindfulness to counseling students through yoga, meditation, and Qigong. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86(1), 47–56.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: a new approach to preventing relapse. New York: Guilford Press.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2013). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Shapiro, S. L., Carlson, L. E., Astin, J. A., & Freedman, B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 373–386. doi:10.1002/jclp.20237.

Shapiro, S. L., Brown, K. W., & Biegel, G. M. (2007). Teaching self-care to caregivers: effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the mental health of therapists in training. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 1(2), 105–115. doi:10.1037/1931-3918.1.2.105.

Siegel, D. J. (2007). The mindful brain: reflection and attunement in the cultivation of well-being. New York: W W Norton & Co.

Stew, G. (2011). Mindfulness training for occupational therapy students. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(6), 269–276. doi:10.4276/030802211x13074383957869.

Thorne, S., Jensen, L., Kearney, M. H., Noblit, G., & Sandelowski, M. (2004). Qualitative metasynthesis: reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qualitative Health Research, 14(10), 1342–1365. doi:10.1177/1049732304269888.

Walsh, B., & Walsh, S. (2001). Is mental health work psychologically hazardous for staff? A critical review of the literature. Journal of Mental Health, 10(2), 121–129. doi:10.1080/09638230123742.

Young, L. E., Bruce, A., Turner, L., & Linden, W. (2001). Evaluation of a mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention. Canadian Nurse, 97(6), 23–26.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morgan, P., Simpson, J. & Smith, A. Health Care Workers’ Experiences of Mindfulness Training: a Qualitative Review. Mindfulness 6, 744–758 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0313-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0313-3