Abstract

Background

Online video sharing platforms like YouTube (Google LLC, San Bruno, CA, USA) have become a substantial source of health information. We sought to conduct a systematic review of studies assessing the overall quality of perioperative anesthesia videos on YouTube.

Methods

We searched Embase, MEDLINE, and Ovid for articles published from database inception to 1 May 2023. We included primary studies evaluating YouTube videos as a source of information regarding perioperative anesthesia. We excluded studies not published in English and studies assessing acute or chronic pain. Studies were screened and data were extracted in duplicate by two reviewers. We appraised the quality of studies according to the social media framework published in the literature. We used descriptive statistics to report the results using mean, standard deviation, range, and n/total N (%).

Results

Among 8,908 citations, we identified 14 studies that examined 796 videos with 59.7 hr of content and 47.5 million views. Among the 14 studies that evaluated the video content quality, 17 different quality assessment tools were used, only three of which were externally validated (Global Quality Score, modified DISCERN score, and JAMA score). Per global assessment rating of video quality, 11/13 (85%) studies concluded the overall video quality as poor.

Conclusions

Overall, the educational content quality of YouTube videos evaluated in the literature accessible as an educational resource regarding perioperative anesthesia was poor. While these videos are in demand, their impact on patient and trainee education remains unclear. A standardized methodology for evaluating online videos is merited to improve future reporting. A peer-reviewed approach to online open-access videos is needed to support patient and trainee education in anesthesia.

Study registration

Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/ajse9); first posted, 1 May 2023.

Résumé

Contexte

Les plateformes de partage de vidéos en ligne comme YouTube (Google LLC, San Bruno, CA, États-Unis) sont devenues une source importante d’informations sur la santé. Nous avons cherché à réaliser une revue systématique des études évaluant la qualité globale des vidéos d’anesthésie périopératoire sur YouTube.

Méthode

Nous avons recherché des articles dans Embase, MEDLINE et Ovid publiés depuis la création de ces bases de données jusqu’au 1er mai 2023. Nous avons inclus des études primaires évaluant les vidéos YouTube comme source d’information sur l’anesthésie périopératoire. Nous avons exclu les études publiées dans une langue autre que l’anglais et les études évaluant la douleur aiguë ou chronique. Les études ont été examinées et les données ont été extraites en double par deux personnes. Nous avons évalué la qualité des études selon le cadre des médias sociaux publié dans la littérature. Nous avons utilisé des statistiques descriptives pour rapporter les résultats en utilisant la moyenne, l’écart type, la plage et n/total N (%).

Résultats

Parmi 8908 citations, nous avons identifié 14 études qui ont examiné 796 vidéos avec 59,7 heures de contenu et 47,5 millions de vues. Parmi les 14 études qui ont évalué la qualité du contenu vidéo, 17 outils d’évaluation de la qualité différents ont été utilisés, dont seulement trois ont été validés en externe (Score Global Quality, score DISCERN modifié et score JAMA). Selon l’évaluation globale de la qualité des vidéos, 11 études sur 13 (85 %) ont conclu que la qualité globale des vidéos était médiocre.

Conclusion

Dans l’ensemble, la qualité du contenu éducatif des vidéos YouTube évaluées dans la littérature accessible en tant que ressource éducative concernant l’anesthésie périopératoire était médiocre. Bien que ces vidéos soient très demandées, leur impact sur la formation de la patientèle et des stagiaires reste incertain. Une méthodologie normalisée d’évaluation des vidéos en ligne est nécessaire pour améliorer les évaluations futures. Une approche évaluée par les pairs pour les vidéos en libre accès en ligne est nécessaire pour soutenir la formation de la patientèle et des stagiaires en anesthésie.

Enregistrement de l’étude

Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/ajse9); première publication le 1er mai 2023.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Social media has become commonplace in modern society as a means for individuals to communicate and interact in real-time digital environments. Increasingly, both patients and health care providers are using such platforms to learn and share health care related information.1 More than 50% of patients are using social media as a means to access health care information.2 Video sharing platforms, a subset of social media, are becoming increasingly popular sources of information. YouTube (Google LLC, San Bruno, CA, USA), a video sharing platform, receives more than two billion active users a month, rendering it the most popular video sharing platform.3 As a result of its widespread popularity, it ranks second in total global internet traffic.4 Patients are increasingly accessing open access video sharing platforms like YouTube in search of health-related knowledge.1 YouTube’s widespread use and open access nature has resulted in the creation of a substantial repository of predominantly nonpeer-reviewed health information. With such widespread use and vast amounts of information, it is critical to appraise the quality of the information that is shared on the platform.

There has been an exponential increase in the number of studies published in the medical literature using data from social media.5 Yet, there have been no systematic reviews investigating the literature assessing perioperative anesthesia information on YouTube whereas this has been evaluated in other disciplines.6 It is understood that patients are increasingly using the internet to access health-related information. Nevertheless, inaccurate information may cause confusion and undue concern for patients,7 prompting the need for high-quality, regulated, and patient-centred information on the internet. In addition, there has been an increasing uptake by medical trainees and physicians using open access platforms like YouTube to gain further knowledge.8

With the large prevalence of patients using YouTube as a source of health information, it is important to appreciate its uses, limitations, and current uptake among patients that will be receiving care from anesthesiologists. Such work will provide a foundation for future investigations and health policy. As such, our aim was to conduct a systematic review to assess the overall quality of perioperative anesthesia videos on YouTube reviewed in the literature.

Methods

Study methodology and search strategy

This systematic review is reported in adherence to the standards and guidelines established in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement where applicable (Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] eTables 1 and 2).9 The project was registered on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/ajse9; first posted 1 May 2023). We conducted comprehensive searches of the literature using the databases Embase, MEDLINE, and Ovid HealthSTAR, from inception until 1 May 2023. The search strategy was developed in consultation with a health sciences librarian and peer reviewed according to the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) guidelines.10 We used a combination of keywords, including “YouTube,” “health care,” “information,” and “surgery.” Search strategies can be found in ESM eTable 3. We reviewed the reference lists of included studies for possible additional studies.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria for article selection were studies that were original research articles that investigated YouTube as a source of patient or trainee information for any topic regarding perioperative anesthesia (including but not limited to general anesthesia, regional blocks, and obstetrical anesthesia).

Exclusion criteria included articles outside of the defined scope, articles not examining YouTube as a source of patient information, reviews (although the citations of these papers were reviewed and extracted to the screening process), commentaries, editorials, guidelines, news articles, conference abstracts/proceedings, articles without an associated full text, and articles in a language other than English. We also excluded articles reporting studies investigating acute and chronic pain.

Study selection

All citations were imported into EndNote® X7 (Thomson Reuters, Toronto, ON, Canada) and underwent deduplication, which was manually confirmed to be accurate. Study screening was conducted in a two-stage process. First, two reviewers (two of A. P. J., M. N., M. V.) independently screened the titles and abstracts of each article in accordance with the inclusion criteria. This was preceded by pilots of 100 studies each to ensure that the interrater reliability (kappa) was greater than 0.6. Two reviewers (two of A. P. J., M. N., M. V.) then independently conducted full-text screening according to the inclusion criteria. During both stages, discrepancies were resolved through joint discussion and consensus among the two reviewers and a senior author (M. S.).

Data extraction and analysis

Data were extracted into Microsoft® Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and in duplicate by two independent reviewers (two of A. P. J., M. N., M. V.). Discrepancies in data extraction were resolved through joint discussion with a senior author (M. S.). Data extraction parameters included study meta-data (year of publication, publishing journal), methodological data (study objective, search criteria and search methodology used, type of analysis conducted), type of anesthesia, quantitative data regarding videos examined (video duration, views), educational video quality, and video source. The target audience was also assessed for each included paper.

For studies that reported only median and interquartile ranges [IQRs] or ranges, mean and standard deviation (SD) were imputed from the median and with methods proposed by Luo et al.,11 Shi et al.,12 and Wan et al.13 following normality tests. In cases where data were missing from the published study, an email was sent to the author asking for access to the raw data.

Where overall quality of videos was assessed in a study, the overall educational quality of videos in a study was assessed as being either “poor,” “fair,” or “good,” as indicated by the authors’ global assessment of the videos in the study conclusion or discussion. Where multiple scales were used to evaluate the quality of the videos in the study, this approach was taken as well. Where authors did not explicitly comment on the overall educational quality of the videos, the overall assessment was determined according to a validated assessment scale (if one was used). If a validated assessment scale was not used and an author-generated scale was used instead, the quality was deemed to be “poor” if the score was 33% or lower, “fair” if between 33 and 66%, and “good” if above 66%.

We appraised the quality of individual studies using the framework published by D’Souza et al.14 This is a framework focusing on five overarching questions to assist authors in appraising studies using data from social media platforms. Each study was assessed according to the framework and a binary score (“Yes/No”) was reported for each category. The overall study quality was graded as “good” if the score was ≥ 7, “fair” if the score was ≤ 6 and ≥ 3, and “poor” if the score was ≤ 2.

The video uploader source was divided into the following categories: academic institution/affiliation; advertisers/commercial/media; health care organization; patient/public; physician; other health care practitioner; and other.

Because of significant heterogeneity and the inability to preclude double counting, quantitative meta-analysis was not conducted. We used descriptive statistics to report the results using mean, SD, range, and n/total N (%). We generated heatmaps to visualize the proportion of videos uploaded from the aforementioned sources. We calculated Cohen’s kappa to assess interrater reliability. We used Fisher’s exact test to compare the proportion of videos that were rated as poor among anesthesia techniques studied. In all statistical tests, was used an alpha value of 0.05 to declare statistical significance.

Results

Study selection

The initial literature search across three databases yielded 8,908 articles (Figure). Following the removal of 4,353 duplicates, we screened the titles and abstracts 4,555 of studies. We assessed a total of 20 full-text articles for eligibility, yielding 14 articles in the final analysis. The interrater reliability was 0.94 for title and abstract screening and 0.85 for full-text screening.

Study characteristics

Articles were published between 2012 and 2023, with a median publication year of 2020. Half of the papers (7/14) were published in the last three years alone (2020–2023). Table 1 details individual study characteristics.15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 Nine of 14 (64%) authors were contacted to access missing data, 3/9 (33%) authors responded to the correspondence, and 2/3 (66%) of those authors provided additional data.

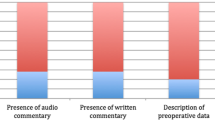

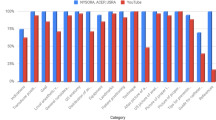

Among the 14 studies included, there were 796 videos with 59.7 hr of video content and 47.5 million views. Studies included a mean (SD) of 47 (44) videos (Table 2). Regional anesthesia was studied most frequently (six, 43%), followed by vascular access (three, 22%), intubation (two, 14%), obstetrical anesthesia (two, 14%) and least frequently, general anesthesia (one, 7%) (ESM eFig. 1). Cumulatively, the mean video duration ranged from 2.3 to 11.5 min, with a mean video view count range of 1,348–486,933.

Overall, 12/14 (86%) of the included studies had multiple raters for video review, and of those that did, 7/12 (58%) calculated and reported an interrater agreement. All studies conducted a content analysis. In terms of a study quality, 50% of the studies were graded as good, 50% as fair, and 0% as poor (Table 3).

In total, 14/14 (100%) studies conducted a quality assessment of videos, with 12/14 (86%) reporting the overall educational quality of videos as poor and 2/14 (14%) as good (Table 1). Among the 14 studies, a total of 17 different tools were used to assess quality, three of which were from the peer-reviewed literature while the remaining 14 were author-generated. The JAMA score was used in three studies (two reported findings) with a mean range of 0.7–1.5 out of a possible maximum of four points (Table 2). The Global Quality Score was used in two studies, with a mean range of 1.7–3.7 out of a possible maximum of five points. The modified DISCERN was employed in two studies, with a mean range of 1.5–3.7 out of a possible maximum of five points.

There were no statistically significant difference in the proportion of videos that were rated as poor among anesthesia techniques studied (Fisher’s exact test, P = 1.0) (Table 2).

Overall, 7/14 (50%) studies were graded as good on methodological quality assessment whereas 7/14 (50%) were graded as fair and none graded as poor (Table 3). Studies most commonly lost points for failing to provide future directions (5/14) and for having insufficient data (7/14).

Approximately one third of videos were uploaded by sources that would be considered educationally reputable (academic institutions, health care organizations, physicians, or other health care practitioner) (35.4%), whereas 32.4% of videos did not have an upload source reported (ESM eFig. 2).

Discussion

Key findings

This systematic review investigated the educational quality of perioperative anesthesia videos for patients and trainees on YouTube that have been evaluated in the academic literature. The main findings were that 1) the overall educational quality of videos was poor, and the methodological quality of studies was fair; 2) the majority of the literature was published within the last several years and continues to grow rapidly; and 3) there is substantial heterogeneity in the tools used to evaluate quality within the literature. These findings are important because they highlight that YouTube is a social media platform actively used to educate patients and trainees alike on topics encompassing anesthesia; however, the overall quality of such information was found to be poor according to individual studies’ global conclusions.

There appears to be a growing demand for videos discussing anesthesia for both patients and trainees as evidenced by the 796 videos and 47.5 million views included within this review. There likely are many excellent, high-quality videos on a variety of anesthesia topics posted to YouTube; however, clinicians should remain cautious in recommending YouTube as a sole or primary educational solution for trainees and patients. This concern regarding the quality of health care information on the internet is not new. Keelan et al. investigated the quality of health care information available on YouTube.29 They found that more than half of the immunization videos on YouTube contained information that contraindicated the reference standard. These findings are consistent with our observations that the majority of YouTube videos discussing anesthesia topics and evaluated in the literature were found to be of low educational quality. Dissemination of misleading information carries a substantial risk, which may be implicated in negative effects on patient care.7 The lack of peer review prior to uploading videos to YouTube, or any open access platform, is evidently a problem that continues to grow. It is likely challenging for patients and some trainees to critically evaluate the information on its own. There is a need for strategies to identify high-quality educational content for patients and trainees on anesthesia. YouTube recently has made efforts to label videos from accredited health care sources to assist viewers in evaluating the trustworthiness of information.30

The literature appears to be generally united in the observation of low-quality videos on anesthesia topics posted to YouTube. The platform is designed for entertainment rather than educational purposes and the proprietary algorithm appears to function in a manner that promotes videos that users engage more with. There are likely a number of factors, such as search history, geographic location, and age that affect video sequence on YouTube. High-quality peer-reviewed information designed for patients is available online in a variety of formats, including webpagesFootnote 1 and videos.Footnote 2 Despite the existence of these resources, patients and trainees continue to access YouTube, likely because of its widespread popularity and ease of use. Moreover, multimedia modalities of education will likely continue to increase, and as some work has observed, it can significantly improve the understanding of complex topics.31 Therefore, this study is important because it provides a comprehensive evaluation of the literature assessing videos for trainee and patient education regarding anesthesia on YouTube.

We found that a substantial portion of the literature investigating YouTube as a source of patient and trainee education has been published in the recent past. A total of 17 unique tools were used to assess video quality across the included studies, three of which were from the peer-reviewed literature while the remaining 14/17 were author-generated. Study authors should consider incorporating commonly employed tools to assess videos in future studies (Table 4). Tools such as the DISCERN,32 the JAMA score,33 and Global Quality Scale34 are examples that should be incorporated into future projects. Similarly, the use of author-generated tools should be avoided when a validated instrument for the same purpose has been developed. In this review, we found that a high number of authors independently developed tools to assess videos on YouTube, with some failing to cite peer-reviewed publications regarding best practices.18,22 Without appropriate validation and insufficient details regarding the methods of developing such tools, the implications of the outcomes may be difficult to appreciate. Moreover, multiple raters should review videos and interrater reliability of their evaluation should be quantitatively assessed using statistics such as Cohen’s Kappa.35 Many of the studies failed to reduce the risk of bias by not employing multiple raters to assess videos.

The framework proposed by D’Souza et al. served as a novel tool to evaluate study methodological quality.14 As shown in Table 3, the vast majority of studies suffered in three key areas of assessment, particularly with regards to limitations, inconsistency, and future directions. Many of the studies reviewed employed quality assessment tools that were not validated and/or did not reference peer-reviewed literature, which is a major limitation. In addition, when studies failed to include multiple raters and/or report assessment of interrater reliability, they were deemed inconsistent. Lastly, the vast majority of studies failed to discuss future directions. This is a substantial issue as the authors engaged with this area of literature are important stakeholders in advancing our understanding and highlighting key knowledge gaps for future study.

Strengths and limitations

A primary limitation of the current review is the lack of a validated quality assessment tool to assess the rigour of included studies. Although D’Souza et al. have published a framework to appraise studies investigating social media, the tool has not been validated.14 No validated instrument has been developed to assess the overall quality of studies investigating social media and medical information. Future work should aim to develop a validated instrument similar to the GRADE tool36 to assess study quality. Moreover, given the tremendous heterogeneity of tools deployed for evaluating video quality, we were unable to provide a more precise estimation of quality. With the above suggestions, future work may be able to provide increasingly detailed analyses. In addition, given the lack of detail provided in the original studies, we were only able to quantitatively pool composite scores, as opposed to analyzing the underlying components of these scores (e.g., DISCERN). This is further challenged by the lack of data associated with outcomes, such as patient knowledge. The systematic search was restricted to studies published in English, potentially rejecting important papers published in other languages.

There are several important strengths of this review that merit consideration. There was high interrater reliability across data extraction and subsequent analyses. The search strategy deployed was extremely sensitive, as highlighted by the number of titles included in the preliminary screening compared with the final sample.

Recommendations and next steps

Ongoing work should focus on the incorporation of peer-reviewed and/or validated assessment instruments for assessing the educational quality of videos. This will serve to reduce the heterogeneity of assessment outcomes, permitting consistency of reporting and facilitation of aggregation across the body of literature. Table 4 summarizes recommendations for studies investigating digital information in health care, like perioperative anesthesia on YouTube. If authors choose to develop novel assessment tools for a given aspect of anesthesia, this should be done in reference to the peer-reviewed literature and the development process should be properly described. Strategies for improving the educational quality of available videos on YouTube and the internet more broadly are needed, with future investigation of the effect that such information has on patient knowledge, decision-making, and potentially even clinical outcomes. How video quality affects measurable outcomes for both patients and trainees should also be measured in future studies.

Trainee education is always evolving, and new modalities of education are frequently incorporated in an effort to improve educational outcomes. The learning outcomes associated with the use of freely available online videos on trainee education merit attention. Identifying characteristics that lend videos to be classified as providing high-quality educational information and how trainees develop as a result of engaging with such information should be studied. Previous literature has shown the improved learning outcomes when videos were included as part of medical trainee educational material.37

Recently, YouTube launched a pilot program with the Council of Medical Specialty Societies and the National Academy of Medicine to identify credible source of health-related information on the platform.30 This is one example of efforts that can be made to possibly improve the ease by which individuals can access credible and reliable information online.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this systematic review found that the overall educational quality of patient- and trainee-targeted videos on perioperative anesthesia on YouTube have been reviewed as poor quality. There is certainly demand for such videos; however, the impact of inaccurate information for patients and trainees is not fully understood. A standardized methodology for evaluating online videos is merited to improve future reporting. More importantly, a peer-reviewed approach to online open-access videos is needed to support online patient and trainee education in anesthesia.

Notes

American Society of Anesthesiologists. Resources. Available from URL: https://www.asahq.org/madeforthismoment/resources/ (accessed March 2024).

NYSORA. Videos. Available from URL: https://www.nysora.com/topics/educational-tools/videos (accessed March 2024).

References

D’Souza RS, Daraz L, Hooten WM, Guyatt G, Murad MH. Users’ guides to the medical literature series on social media (part 1): how to interpret healthcare information available on platforms. BMJ Evid Based Med 2022; 27: 11–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2021-111817

Surani Z, Hirani R, Elias A, et al. Social media usage among health care providers. BMC Res Notes 2017; 10: 654. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2993-y

Dean B. How many people use YouTube [new data]? Available from URL: https://backlinko.com/youtube-users (accessed March 2024).

Semrush. youtube.com web traffic statistics. Available from URL: https://www.semrush.com/website/youtube.com/overview/ (accessed April 2024).

D’Souza RS, Hooten WM, Murad MH. A proposed approach for conducting studies that use data from social media platforms. Mayo Clin Proc 2021; 96: 2218–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.02.010

Javidan A, Nelms MW, Li A, et al. Evaluating YouTube as a source of education for patients undergoing surgery: a systematic review. Ann Surg 2023; 278: e712–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000005892

Wang Y, McKee M, Torbica A, Stuckler D. Systematic literature review on the spread of health-related misinformation on social media. Soc Sci Med 2019; 240: 112552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112552

Rapp AK, Healy MG, Charlton ME, Keith JN, Rosenbaum ME, Kapadia MR. YouTube is the most frequently used educational video source for surgical preparation. J Surg Educ 2016; 73: 1072–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.04.024

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372: n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2016; 75: 40–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021

Luo D, Wan X, Liu J, Tong T. Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat Methods Med Res 2018; 27: 1785–805. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280216669183

Shi J, Luo D, Weng H, et al. Optimally estimating the sample standard deviation from the five-number summary. Res Synth Methods 2020; 11: 641–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1429

Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014; 14: 135. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-135

D’Souza RS, Daraz L, Hooten WM, Guyatt G, Murad MH. Users’ guides to the medical literature series on social media (part 2): how to appraise studies using data from platforms. BMJ Evid Based Med 2022; 27: 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2021-111850

Rössler B, Lahner D, Schebesta K, Chiari A, Plöchl W. Medical information on the Internet: quality assessment of lumbar puncture and neuroaxial block techniques on YouTube. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2012; 114: 655–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.12.048

Carr PJ, Alexandrou E, Jackson GM, Spencer TR. Assessing the quality of central venous catheter and peripherally inserted central catheter videos on the YouTube video-sharing web site. J Assoc Vasc Access 2013; 18: 177–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.java.2013.06.001

Tulgar S, Selvi O, Serifsoy TE, Senturk O, Ozer Z. YouTube as an information source of spinal anesthesia, epidural anesthesia and combined spinal and epidural anesthesia [Portuguese]. Braz J Anesthesiol 2017; 67: 493–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjan.2016.08.007

Ocak U. Evaluation of the content, quality, reliability and accuracy of YouTube videos regarding endotracheal intubation techniques. Niger J Clin Pract 2018; 21: 1651–5. https://doi.org/10.4103/njcp.njcp_207_18

Selvi O, Tulgar S, Senturk O, Topcu DI, Ozer Z. YouTube as an informational source for brachial plexus blocks: evaluation of content and educational value [Portuguese]. Braz J Anesthesiol 2019; 69: 168–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjan.2018.11.004

De Cassai A, Correale C, Sandei L, Ban I, Selvi O, Tulgar S. Quality of erector spinae plane block educational videos on a popular video-sharing platform. Cureus 2019; 11: e4204. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.4204

Sevinc M. Educational value of Internet videos in vascular access. J Vasc Access 2019; 20: 537–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1129729819845956

Tewfik GL, Work AN, Shulman SM, Discepola P. Objective validation of YouTube educational videos for the instruction of regional anesthesia nerve blocks: a novel approach. BMC Anesthesiol 2020; 20: 168. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-020-01084-w

Arslan B, Sugur T, Ciloglu O, Arslan A, Acik V. A cross-sectional study analyzing the quality of YouTube videos as a source of information for COVID-19 intubation. Braz J Anesthesiol 2021; 72: 302–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2021.10.002

Cho NR, Cha JH, Park JJ, Kim YH, Ko DS. Reliability and quality of YouTube videos on ultrasound-guided brachial plexus block: a programmatical review. Healthcare 2021; 9: 1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9081083

D’Souza RS, D’Souza S, Sharpe EE. YouTube as a source of medical information about epidural analgesia for labor pain. Int J Obstet Anesth 2021; 45: 133–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijoa.2020.11.005

Flinspach AN, Raimann FJ, Schalk R, et al. Epidural catheterization in obstetrics: a checklist-based video assessment of free available video material. J Clin Med 2022; 11: 1726. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11061726

King D, Davison D, Benjenk I, et al. YouTube to teach central lines, the expert vs learner perspective. J Intensive Care Med 2022; 37: 528–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885066621999979

Kartufan FF, Bayram E. The evaluation of YouTubeTM videos pertaining to intraoperative anaesthesia awareness: a reliability and quality analysis. Cureus 2023; 15: e35887. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.35887

Keelan J, Pavri-Garcia V, Tomlinson G, Wilson K. YouTube as a source of information on immunization: a content analysis. JAMA 2007; 298: 2482–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.21.2482

Kington RS, Arnesen S, Chou WY, Curry SJ, Lazer D, Villarruel AM. Identifying credible sources of health information in social media: principles and attributes. Available from URL: https://nam.edu/identifying-credible-sources-of-health-information-in-social-media-principles-and-attributes/ (accessed March 2024).

Pape-Koehler C, Immenroth M, Sauerland S, et al. Multimedia-based training on Internet platforms improves surgical performance: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc 2013; 27: 1737–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-012-2672-y

Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann R. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health 1999; 53: 105–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.53.2.105

Silberg WM, Lundberg GD, Musacchio RA. Assessing, controlling, and assuring the quality of medical information on the Internet: caveant lector et viewor—let the reader and viewer beware. JAMA 1997; 277: 1244–5.

Bernard A, Langille M, Hughes S, Rose C, Leddin D, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S. A systematic review of patient inflammatory bowel disease information resources on the World Wide Web. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102: 2070–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01325.x

McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2012; 22: 276–82.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008; 336: 924–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.ad

Romanov K, Nevgi A. Do medical students watch video clips in eLearning and do these facilitate learning? Med Teach 2007; 29: 484–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701542119

Author contributions

Matthew W. Nelms, Arshia Javidan, Ahmed Kayssi, and Faysal Naji conceived the study design. Matthew W. Nelms, Arshia Javidan, and Muralie Vignarajah conducted data extraction. Fangwen Zhou and Yung Lee designed the data processing and analytical plan. Chenchen Tian, Ki Jinn Chin, and Mandeep Singh provided intellectual contributions to the interpretation of the results and preparation of the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and provided intellectual contributions to the composition of the final manuscript. Matthew W. Nelms and Arshia Javidan contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding statement

No external funding was received. Mandeep Singh is supported by the Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society Career Scientist Award, and the Merit Award Program from the Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON.

Prior conference presentations

Preliminary data from this project was presented at the 2022 American Society of Anesthesiologists Annual Meeting (21–25 October, New Orleans, LA, USA).

Data availability

Access to data is available on request from the authors.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Philip M. Jones, Deputy Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Nelms, M.W., Javidan, A., Chin, K.J. et al. YouTube as a source of education in perioperative anesthesia for patients and trainees: a systematic review. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 71, 1238–1250 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-024-02791-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-024-02791-5