Abstract

Purpose of Review

In patients undergoing mastectomy, benefits of nipple preservation include improved esthetics and quality of life. The purpose of this review is to evaluate the oncologic safety of nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) in women with breast cancer, focusing on complications, recurrence, and patient reported outcomes.

Recent Findings

Clinical presentation, risk factors for nipple involvement, and preoperative imaging may be helpful in choosing appropriate candidates. Recent series suggest that complications after NSM are slightly increased when compared to traditional mastectomy but likely related to increased risk of nipple necrosis. Pathologic assessment of the nipple is necessary. Local recurrence after NSM appears similar to patients after traditional mastectomy; however, studies evaluating local recurrence are of lower quality and have short follow-up. NSM is associated with improved psychosocial and sexual well-being after surgery.

Summary

Studies evaluating oncologic safety of therapeutic NSM suggest that it is a viable option for appropriate patients, as risk of local recurrence and survival appears to be similar to patients undergoing traditional mastectomy. However, careful patient selection is critical.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

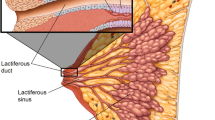

Studies evaluating breast reconstruction have shown that the presence of a nipple is associated with improved body image and quality of life after mastectomy. This finding is postulated to be a result of a more finished appearance to the breast and better symmetry with the contralateral breast in patients undergoing unilateral mastectomy. Reconstruction of the nipple areolar complex (NAC) improves the psychological impact, but outcomes after nipple reconstruction are somewhat variable. Loss of projection of the papilla, change in color or shape when compared to the contralateral breast, and lack of sensation have all been associated with patient dissatisfaction [1].

Nipple preservation offers an appealing alternative to nipple reconstruction for appropriate patients undergoing mastectomy. Historically, nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) was performed for prophylactic indications in women deemed high risk for development of breast cancer based on genetic carrier status, family history, or other pathology. The group chosen for this procedure was based on a landmark trial by Hartmann and colleagues published in 1999 that demonstrated 93% risk reduction with the use of prophylactic mastectomy in the high-risk population [2]. Since that time, the indications for NSM have expanded to include certain patients undergoing therapeutic mastectomy for breast cancer. The purpose of this review is to evaluate the oncologic safety, risk of complications, and quality of life outcomes of NSM in this population.

Preoperative Decision-Making

In patients with breast cancer, the goal of NSM is to remove the same amount of tissue as traditional mastectomy without compromising oncologic outcomes. Retrospective trials show pathologic nipple involvement to occur 5–12% of mastectomies, but some are reported as high as 58% [Fig. 1] [3••]. The patient’s clinical presentation at diagnosis serves as primary methodology to determine eligibility for nipple preservation; contraindications include pathologic nipple discharge and skin changes consistent with Paget’s disease [4]. However, the majority of patients with invasive or in situ carcinoma within the base of the nipple lack visible symptoms. It can be difficult to predict preoperatively with breast examination and conventional imaging alone who is an appropriate candidate [5].

Preoperative breast MRI may play a role in selecting appropriate candidates. As demonstrated by a retrospective cohort analysis of 137 women who underwent breast MRI prior to definitive mastectomy, the presence of non-mass-like enhancement extending up to the nipple was associated with significant risk of nipple involvement (incidence 52.7%, OR 21.7, p = 0.003). If the enhancement did not extend directly to the nipple, the incidence of nipple involvement was 6.1% and did not appear to be significantly different with a 2 cm threshold (p = 0.46) [6]. These findings are in contrast to data published by Mariscotti and colleagues who noted that the distance from the nipple on MRI was significant on multivariate analysis. The authors suggested that a 1-cm distance from the nipple allows for 81% diagnostic accuracy with improved sensitivity and specificity for predicting nipple involvement [7].

There is no widely accepted location for incision for NSM; the decision regarding placement depends on multiple factors, including tumor location, breast size, ptosis, and planned method of reconstruction. Inframammary incisions allow for the scar to be located under the reconstructed breast which result in excellent esthetics. However, this approach can be technically difficult to resect tissue from the upper pole of the breast in patients with large, ptotic breasts, and require a counter incision for patients undergoing axillary surgery. Peri-areolar and radial incisions that split the breast allow for better visualization for patients with all breast sizes and allow for access to the axilla more easily [8]. These may also be utilized more commonly by surgeons with less experience performing NSM.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network panel states that pathologic assessment of the nipple margin is mandatory for patients undergoing therapeutic NSM [4]. There is variation between practice settings as to whether frozen sectioning (FS) of the retro-areolar tissue is routinely performed versus routine permanent sectioning. Knowledge of pathology intraoperatively allows for immediate guidance regarding the need to excise the nipple, thereby saving the patient additional surgery. Resection of the nipple results in a smaller residual skin envelope that may affect implant size in patients undergoing immediate direct-to-implant reconstruction. Retrospective studies reveal FS to have moderate sensitivity (58–80%) and high specificity (88–100%). False-positive results are rare, and false-negative rates range from 2 to 6% [9,10,11]. These rates are likely due to sampling error, tissue loss during processing, or artifacts from diathermy and freezing. Suarez-Zamora and colleagues were the first to evaluate interobserver agreement in retro-areolar FS of 34 NSM; concordance between breast pathologists was higher than general pathologists (kappa value 0.87 vs 0.31, p < 0.0001) [9]. The decision whether to incorporate routine intraoperative FS is unique to each institutional practice setting based on resources; however, a cost analysis performed by Alperovich in 2016 showed routine FS in this setting adds $95 per breast [10]. In patients with positive nipple margins detected on permanent sectioning, resection of the nipple is recommended, as 40% of patients have disease within the nipple on final pathology of re-excision [11].

There has been some postulation that the use of NSM would result in increased rates of positive margins in other areas of the breast due to lack of visualization when compared to traditional skin sparing mastectomy (SSM). However, as demonstrated by a review from the National Cancer Database, there was no difference in rates of positive margins between the two approaches (4.1% NSM vs 3.9% SSM, p = 0.6) [12]. Additionally, as the indications expand for patients with more extensive disease, it is reassuring that utilization of NSM does not appear to delay receipt of adjuvant therapies such as chemotherapy, radiation, or endocrine therapy [12, 13].

Complications

Studies are conflicting as to whether NSM is associated with increased risk of surgical complications. The overall complication rates range from 20 to 25% as shown by two systematic reviews [2, 14]. This finding is likely a result of technical factors, as the approach required for enhanced cosmesis and nipple preservation may result in tension on the skin flaps and nipple, leading to necrosis. A Cochrane review comparing NSM to other types of mastectomy concluded that there did not appear to be an increase in adverse events with NSM [15]. This review is in stark contrast to the findings reported by others, including Agha et al., who noted a significant increase in complications with NSM when compared to SSM (22.6% vs 14.0%). The higher complication rate is attributed to the risk of nipple necrosis, which is not an issue when the nipple is removed [3••, 16•, 17••]. Interestingly, the potential increase in complications with NSM does not appear to translate to higher rates of readmission or reoperation [17••]. Moreover, these results may be time and experience dependent. Headon et al. noted a significant reduction in both overall complications and nipple necrosis when comparing studies performed prior to and after 2013. This finding was attributed to improvements in surgical technique and increasing surgeons’ comfort with the procedure [14].

Necrosis of the NAC is the most severe complication of NSM, as it can lead to deformity, hypopigmentation, or loss of the NAC [18]. Rates of nipple necrosis as showed by recent retrospective institutional series range from 0.2 to 16.7% (Table 1). Patients with central tumors close to the nipple may be at increased risk. As shown by Park and colleagues, for every 1 cm increase in tumor-nipple-distance, there was a 0.712-fold reduction in nipple necrosis (p = 0.012) [18]. These findings are similar to the study by Balci et al. that demonstrated patients with tumors within 2 cm of the nipple have increased risk of complete NAC necrosis (5.1% vs 0.7%, p = 0.028) [19]. Although the risk is elevated with central tumors, the risk of NAC necrosis is still low. Careful dissection of the tissue behind the nipple is crucial in order to preserve the blood supply while achieving negative margins.

Multiple authors have sought to evaluate whether the choice of skin incision in NSM affects risk of complications. Garwood and colleagues demonstrated that incisions that cross the areola or utilize > 30% of its border are associated with 3.8-fold higher rates of NAC necrosis [20]. These findings were confirmed by Park et al., who concluded that the type of incision was significantly associated with risk of nipple necrosis in 275 patients who underwent NSM with immediate reconstruction (p < 0.001). Peri-areolar incisions were associated with highest risk when compared to radial and inframammary incisions [8, 18].

Authors have reported other risk factors for complications after NSM. Larger breast size and weight of the mastectomy specimen have also been associated with increased risk of NAC necrosis on multivariate analysis (p = 0.014). Possible explanations of this relationship are anatomical, with longer distance of the source of blood supply to the nipple, and technical, with potential increased tension applied on the skin in order to achieve adequate visualization during surgery [8].

Smoking has been long associated with higher surgical morbidity secondary to subclinical microvascular disease. Not surprisingly, as viability of NAC and skin flaps after NSM relies on the microvasculature, multiple studies have confirmed a higher risk of complications in patients who smoke [3••, 14, 21]. Frey and colleagues noted a significant difference with a 10 pack-year history of tobacco use, current smokers, and those within 5 years of quitting [21].

Others have sought to determine whether the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to NSM impacted rates of surgical complications when compared to patients undergoing primary surgery. In a cohort of 832 patients over a 28-year span, Bartholomew and colleagues noted similar 30-day surgical complication rates with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (5.7%) vs. primary surgery (10.6%). The authors concluded that NSM was safe in this group of patients [22].

It is well established that radiation therapy (RT) to the breast either before or after surgery is a risk factor for wound healing complications due to fibrotic changes, loss of stem and parenchymal cells, and release of cytokines [23]. In the patients who develop in-breast recurrences after prior breast conserving surgery and RT, decisions must be made as to whether to preserve the nipple. Moreover, as the indications for NSM expand to patients with larger tumors and positive axillary nodes, a significant number of patients may undergo PMRT. The data regarding NSM in the irradiated breast is limited, consisting of single institutional series with small numbers and short follow-up. Two retrospective analyses evaluated the relationship of RT and complications after NSM. Tang et al. compared 166 women with a history of RT (69 prior to NSM and 97 PMRT) to 816 controls, with median follow-up of 23 months. Reish et al. compared 88 women with a history of RT (45 prior and 43 PMRT) to 517 controls, with median follow-up 22 months. As one would expect, the patients who underwent RT did have significantly increased risk of complications, including skin necrosis and nipple loss. However, in both studies, nipple preservation was successful in greater than 90%, and rates of reconstruction failure were less than 8%. Therefore, both studies concluded that history of RT either before or after surgery is not an absolute contraindication for NSM [24, 25].

Oncologic Outcomes

There are no randomized trials evaluating safety and efficacy of NSM for the treatment of breast cancer. The data is limited to institutional series, almost always retrospective, and often includes patients with prophylactic indications. Critics have questioned whether nipple preservation leaves residual terminal duct lobular units (TDLUs), thereby increasing risk of local recurrence (LR). Pathologic examination of nipple and retro-areolar tissue shows presence of TDLUs in only 8% of specimens [11]. Furthermore, the current data using retrospective analyses estimate LR to range from 0.6 to 11.9%, with recurrence in the nipple 0–4.9% (Table 2).

A Cochrane review published in 2016 included 11 studies and compared 6502 participants, including 2259 women who underwent NSM, 818 who underwent SSM, and 3671 women who underwent traditional mastectomy. The risk of LR in patients with NSM was 6.8%, with specific recurrence in the nipple in 1.8%. The conclusion of this review was that the data was insufficient to determine whether there was any difference in LR or survival between the groups. It deemed the quality of evidence to be very low, as there were variances in study design, significant risk of selection bias, and confounding factors that may have affected results. It also noted short study follow-up as a confounding factor, as only 6 of 11 studies within the analysis documented mean follow-up greater than 60 months [15]. To address this issue, Delacruz and colleagues performed a separate analysis of 1212 patients in 6 trials comparing NSM with traditional mastectomy with at least 5 years of follow-up (range 60–136 months). There was no difference in LR, disease-free survival, or overall survival between the 2 groups. Risk of recurrence in the NAC after NSM ranged from 0 to 3.7% [26].

Two additional systematic reviews have been published since the Cochrane analysis. The first, performed by Headon and colleagues, included 73 studies and 10,935 patients. The pooled rate of LR was 2.4% at a mean follow-up 38.3 months (range 7.4–156 months) [14]. Another systemic review and meta-analysis published in 2019 by Agha et al. included 3015 breasts, 1419 treated with NSM and 1596 with SSM. Local recurrence was 3.9% with NSM and 3.3% with SSM, with follow-up ranging from 18 to 101 months (mean not provided). Statistical analysis demonstrated no difference in LR (p = 0.45) or mortality (p = 0.34) between the 2 groups [3••]. Although both reviews suggest a low incidence of LR after NSM, they did not exclude patients undergoing prophylactic surgery, and had relatively short follow-up, which may affect interpretation of results.

Wu and colleagues sought to establish risk factors for LR within the NAC. In their retrospective analysis of 944 women who underwent NSM for invasive breast cancer, 39 (4.1%) developed recurrence at the NAC as first event, with median time to recurrence 35 months. The risk factors for NAC recurrence as shown by multivariate analysis were multifocal/multicentric disease (HR 3.3), presence of extensive intraductal component (HR 3.3), ER negative/HER-2 positive subtype (HR 3.05), and high grade (HR 2.6) [27].

Retrospective studies have been performed looking specifically at outcomes of NSM in patients with other high-risk features such as those who undergo neoadjuvant chemotherapy, have history of prior RT, or need PMRT. As demonstrated in an analysis of 39 women who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to surgery, the use of chemotherapy resulted in significant reduction in the median tumor size (3.1 to 0.9 cm). In addition, in the women deemed cautionary for NSM prior to chemotherapy based on tumor location within 2 cm of the nipple, 90% was able to successfully undergo nipple preservation. At mean follow-up 67.2 months, local recurrence was seen within the tumor bed in 2 of 39 patients (5.1%), and no nipple recurrences were seen [28]. In the two studies evaluating the relationship of RT and outcomes after NSM, local recurrence rates were acceptably low at median follow-up 22–23 months (2.9% pooled result of both studies). No LR was seen in the patients with prior RT and 4 seen in the patients with PMRT [24, 25]. These outcomes are within acceptable ranges for patients with high-risk features.

Patient Satisfaction

The main benefits of nipple preservation and reconstruction are psychological; therefore, patient satisfaction (PS) should be considered an important outcome measure. Assessment of this measure is difficult from a statistical standpoint as it relies on use of patient questionnaires which introduce significant bias. There are also different methods to measure satisfaction, making comparison of different studies more complex.

The BREAST-Q© is a commonly utilized instrument for assessment of patient-reported outcomes after breast surgery. It includes domains focusing on PS and different aspects of health-related quality of life. Wei and colleagues used this instrument to compare PS after surgery in 52 women who underwent NSM to a reference group of 202 women who underwent SSM and NAC reconstruction. On multivariate analysis after adjustment for confounding factors, patients after NSM reported higher psychosocial and sexual well-being compared to their SSM counterparts. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in the domain evaluating physical qualities of the breast reconstruction, such as the softness of the breast and symmetry with the contralateral breast [1]. A matched-pair analysis reported by Yoon-Flannery et al. also noted improved postoperative satisfaction scores in regard to sexual well-being, but no difference in the other domains [29].

The above studies included results from postoperative scores only; it could be questioned whether results may be altered if the preoperative results were included as a comparison. Two separate reviews using the National Cancer Database showed that patients who undergo NSM more likely to be younger, healthier, have smaller body mass indices and more likely to have smaller, earlier stage cancers that are less likely to require adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation [12, 13]. These are all clinical factors that can affect satisfaction.

To assess this baseline difference, an analysis of 513 patients with both preoperative and postoperative BREAST-Q© scores was performed by Romanoff and colleagues (72 patients after NSM and 443 patients after SSM). As predicted above, there were differences in baseline characteristics of the 2 groups, and while patients undergoing NSM had higher median baseline scores, they did not differ significantly from SSM. Additionally, after adjusting for the preoperative scores and clinical variables, NSM was only associated with higher satisfaction of psychological well-being (p = 0.035); the remainder of the scores did not differ significantly [16•].

Satteson et al. performed a more indirect comparison of patient satisfaction after NSM and SSM. Their systemic review included 23 studies evaluating NSM and methods of NAC reconstruction. Since there were multiple instruments utilized within the studies, the authors developed a method to calculate a “satisfaction score” for each study. Overall, patient satisfaction scores were significantly higher in studies evaluating NSM when compared to those evaluating NAC reconstruction (weighted average 80.5% vs 73.9%, p = 0.079) [30].

Patient-reported assessment of nipple-specific outcomes was performed by Peled et al. in 28 women who underwent NSM with immediate expander reconstruction. At 1 year, nearly all patients reported satisfaction with the shape, appearance, and feel of their nipples. However, only 40% of patients reported satisfaction with nipple sensation [31]. Loss of nipple sensation was also seen in a series of 35 patients who underwent NSM. Pinprick tests revealed partial recovery of nipple sensation in 44% of patients at 6 months after surgery and 60% of patients at 1 year [32].

Conclusion

In patients undergoing therapeutic mastectomy for breast cancer, there are multiple benefits to nipple preservation including improved esthetics, prevention of need for additional surgery, and improved psychological well-being. Although there are no randomized trials evaluating oncologic safety of NSM in this group, as presented here, the data is promising. The risks of local recurrence and complications are well within acceptable ranges and do not appear to be statistically different when compared to patients undergoing SSM; however, longer follow-up is needed. There is no longer an ideal candidate for NSM; multiple factors should be considered when assessing for eligibility for nipple preservation, including preoperative presentation and risk factors for nipple involvement.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Wei CW, Scott AM, Price AN, et al. Psychosocial and sexual well-being following nipple-sparing mastectomy and reconstruction. Breast J. 2016;22(1):10–7.

Hartmann LC, Schaid DJ, Woods JE, Crotty TP, Myers JL, Arnold PG, et al. Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with a family history of breast cancer. NEJM. 1999;340:77–84.

•• Agha RA, Al Omran Y, Wellstead G, et al. Systematic review of therapeutic nipple-sparing mastectomy versus skin sparing mastectomy. BJS Open. 2019;3:135–45 Most recent and extensive systematic review of 14 studies, demonstrated higher risk of complications with NSM but no statistical difference in LR (p=0.45) or mortality (p=0.34).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Breast cancer (Version 5.2020). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf. .

Cense HA, Rutgers EJ, Cardozo ML, Van Lanschot JJ. Nipple-sparing mastectomy in breast cancer: a viable option? EJSO. 2001;27:521–6.

Jun S, Bae SJ, Yoon JC, et al. Significance of non-mass enhancement in the subareolar region on preoperative breast magnetic resonance imaging for nipple-sparing mastectomy. Clin Breast Cancer. 2020; epublished ahead of print.

Mariscotti G, Durando M, Houssami N, et al. Preoperative MRI evaluation of lesion nipple distance in breast cancer patients: thresholds for predicting occult nipple areola complex involvement. Clin Radiol. 2018;73:735e–45e.

Daar DA, Abdou SA, Rosario L, et al. Is there a preferred incision location for nipple-sparing mastectomy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019:906e–19e.

Suarez-Zamora DS, Barrera-Herrera LE, Palau-Lazaro MA, et al. Accuracy and interobserver agreement of retroareolar frozen sections in nipple-sparing mastectomies. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2017;29:46–51.

Alperovich M, Choi M, Karp NS, Singh B, Ayo D, Frey JD, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy and sub-areolar biopsy: to freeze or not to freeze? Evaluating the role of sub-areolar intraoperative frozen section. Breast J. 2016;22(1):18–23.

Eisenberg RK, Chan JS, Swistel AJ, Hoda SA. Pathological evaluation of nipple-sparing mastectomies with emphasis on occult nipple involvement: the Weill-Cornell experience with 325 cases. Breast J. 2014;20(1):18–23.

Albright EL, Schroeder MC, Foster K, Sugg SL, Erdahl LM, Weigel RJ, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy is not associated with a delay of adjuvant treatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(7):1928–35.

Wong SM, Chun YS, Sagara Y, Golshan M, Erdmann-Sager J. National patterns of breast reconstruction and nipple-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer, 2005–2015. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:3194–203.

Headon HL, Kasem A, Mokbel K. The oncological safety of nipple-sparing mastectomy: a systematic review of the literature with a pooled analysis of 12,358 procedures. Arch Plast Surg. 2016;43:328–38.

Mota BS, Riera R, Ricci MD, et al. Nipple- and areola-sparing mastectomy for the treatment of breast cancer (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11.

• Romanoff A, Zabor EC, Stempel M, et al. A comparison of patient-reported outcomes after nipple- sparing mastectomy and conventional mastectomy with reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(10):2909–16 This is a well-organized comparison of patient reported outcomes in this setting, demonstrated increased sexual and psychosocial well-being in women with NSM.

•• Wang M, Huang J, Chagpar AB. Is nipple sparing mastectomy associated with increased complications, readmission and length of stay compared to skin sparing mastectomy? Am J Surg. 2020;219(6):1030–5 Extensive evaluation of complications for patients undergoing NSM when compared to SSM. Showed higher rates of complications with NSM likely due to technical complexity but no difference in readmission rates or reoperations.

Park S, Yoon C, Bae SJ, et al. Comparison of complications according to incision types in nipple- sparing mastectomy and immediate reconstruction. Breast. 2020;53 E-published ahead of print.

Balci FL, Kara H, Dulgeroglu O, Uras C. Oncologic safety of nipple-sparing mastectomy in patients with short tumor-nipple distance. Breast J. 2019;25:612–8.

Garwood E, Moore D, Ewing C, et al. Total skin-sparing mastectomy complications and local recurrence rates in 2 cohorts of patients. Ann Surg. 2009;249(1):26–32.

Frey JD, Alperovich M, Levine JP, Choi M, Karp NS. Does smoking history confer a higher risk for reconstructive complications in nipple-sparing mastectomy? Breast J. 2017;23(4):415–20.

Bartholomew AJ, Dervishaj OA, Sosin M, Kerivan LT, Tung SS, Caragacianu DL, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and nipple-sparing mastectomy: timing and postoperative complications. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:2768–72.

Alperovich M, Choi M, Frey JD, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy in patients with prior breast irradiation: are patients at higher risk for reconstructive complications? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(2):202e–6e.

Tang R, Coopey SB, Colwell AS, Specht MC, Gadd MA, Kansal K, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy in irradiated breasts: selecting patients to minimize complications. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3331–7.

Reish RG, Lin A, Phillips NA, Winograd J, Liao EC, Cetrulo CL Jr, et al. Breast reconstruction outcomes after nipple-sparing mastectomy and radiation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(4):959–66.

De La Cruz LM, Moody AM, Tappy EE, et al. Overall survival, disease-free survival, local recurrence, and nipple–areolar recurrence in the setting of nipple-sparing mastectomy: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3241–9.

Wu ZY, Kim HJ, Lee JW, Chung IY, Kim JS, Lee SB, et al. Breast cancer recurrence in the nipple-areola complex after nipple-sparing mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction for invasive breast cancer. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(11):1030–7.

Jadeja P, Ha R, Rohde C, Ascherman J, Grant R, Chin C, et al. Expanding the criteria for nipple-sparing mastectomy in patients with poor prognostic features. Clin Breast Can. 2018;18(3):229–33.

Yoon-Flannery K, DeStefano LM, De La Cruz LM, et al. Quality of life and sexual well-being after nipple sparing mastectomy: a matched comparison of patients using the breast Q. J Surg Oncol. 2018;118:238–42.

Satteson ES, Brown BJ, Nahabedian MY. Nipple-areolar complex reconstruction and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gland Surg. 2017;6(1):4–13.

Peled AW, Duralde E, Foster RD, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and satisfaction after total skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate expander-implant reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72:S48–52.

Chirappapha P, Pongsakorn Srichan P, Lertsithichai P, et al. Nipple-areola complex sensation after nipple-sparing mastectomy. PRS Global Open. 2018;6(4):1–6.

Braun SE, Dreicer M, Butterworth JA, Larson KE. Do nipple necrosis rates differ in prepectoral versus submuscular implant-based reconstruction after nipple-sparing mastectomy? Ann Surg Oncol. 2020; Online ahead of print.

Galimberti V, Morigi C, Bagnardi V, Corso G, Vicini E, Fontana SKR, et al. Oncological outcomes of nipple-sparing mastectomy: a single-center experience of 1989 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(13):3849–57.

Lee CH, Cheng MH, Wu CW, Kuo WL, Yu CC, Huang JJ. Nipple-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction after recurrence from previous breast conservation therapy. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;82:S95–S102.

Margenthaler JA, Gan C, Yan Y, Cyr AE, Tenenbaum M, Hook D, et al. Oncologic safety and outcomes in patients undergoing nipple-sparing mastectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230(4):535–41.

Metere A, Fabiani E, Lonardo MT, Giannotti D, Pace D, Giacomelli L. Nipple-sparing mastectomy long-term outcomes: Early and late complications. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56(4):166.

Parvez E, Martel K, Morency, et al. Surgical and oncologic outcomes of nipple-sparing mastectomy for a cohort of breast cancer patients, including cases with high-risk features. Clin breast Cancer. 2020; Online ahead of print.

Radovanovic Z, Ranisavljevic M, Radovanovic D, Vicko F, Ivkovic-Kapicl T, Solajic N. Nipple sparing mastectomy with primary implant reconstruction: surgical and oncological outcome of 435 breast cancer patients. Breast Care (Basel). 2018;13(5):373–8.

Young WA, Degnim AC, Hoskin TL, Jakub JW, Nguyen MD, Tran NV, et al. Outcomes of > 1300 nipple-sparing mastectomies with immediate reconstruction: The impact of expanding indications on complications. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(10):3115–23.

Alsharif E, Ryu JM, Choi JH, et al. Oncologic outcomes of nipple-sparing mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction in patients with tumor-nipple distance less than 2.0cm. J Breast Cancer. 2019;22(4):613–23.

Frey JD, Salibian AA, Lee J, Harris K, Axelrod DM, Guth AA, et al. Oncologic trends, outcomes and risk factors for locoregional recurrence: an analysis of tumor-to-nipple distance in critical factors in therapeutic nipple-sparing mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(6):1575–85.

Valero MG, Muhsen S, Moo TA, Zabor EC, Stempel M, Pusic A, et al. Increase in utilization of nipple-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer: indications, complications and oncologic outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(2):344–51.

Wu ZY, Kim HJ, Lee J, Chung IY, Kim JS, Lee SB, et al. Recurrence outcomes after nipple-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction in patients with pure ductal carcinoma in situ. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(5):1627–35.

Wu ZY, Kim HJ, Lee JW, et al. Oncologic outcomes of nipple-sparing mastectomy and immediate reconstruction after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Ann Surg. 2020; Online ahead of print.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Local-Regional Evaluation and Therapy

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ludwig, K.K. Oncologic Safety of Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy for Patients with Breast Cancer. Curr Breast Cancer Rep 13, 35–41 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12609-020-00399-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12609-020-00399-4