Abstract

Background

Population aging is increasing and this process together with its characteristics influence the prevalence and incidence of chronic conditions and musculoskeletal-functional outcomes such as frailty, functional disability and sarcopenia. Nutritional strategies focused on dietary patterns, such as a Mediterranean diet, can be protective from these outcomes.

Purpose

To investigate the association between adherence to a Mediterranean diet and frailty, functional disability and sarcopenia in community-dwelling older people.

Methods

We systematically reviewed electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, and others) and grey literature for articles investigating the relationship between adherence to a Mediterranean diet and frailty, functional disability and sarcopenia in community-dwelling people aged 60 and over. Study selection, quality of study assessment and data extraction were conducted independently by two authors. Random effects meta-analyses were performed, and pooled Odds Ratios (OR) were obtained.

Results

After the literature search, screening and eligibility investigation, we included 12studies, with a total of 20,518 subjects. A higher adherence to a Mediterranean diet was found to be inversely associated with frailty (OR 0.42, 95% CI: 0.28-0.65, I2=24.9%, p=0.262) and functional disability (OR 0.75, 95% CI: 0.61-0.93, I2=0.0%, p=0.78). Highly different study characteristics prevented us from performing a meta-analysis for sarcopenia. Cohort data indicated no association between adherence to a Mediterranean diet and sarcopenia; however, cross-sectional results showed a positive relationship.

Conclusion

A Mediterranean diet is protective of frailty and functional disability, but not of sarcopenia. More longitudinal studies are needed to understand the relationship between a Mediterranean diet and sarcopenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A Mediterranean diet is a healthy eating pattern composed of a combination of different types of food and nutrients that have a potential protective effect against chronic diseases and inflammatory conditions. (1, 2) This diet might play an important role, as the prevalence of chronic non-communicable diseases increases among older people due to the phenomenon of rapid population aging in many regions of the world. (3-5)

The Mediterranean diet is characterized by a high intake of nuts, whole grains, vegetables, fruits, fish (a source of polyunsaturated fat); a moderate intake of alcohol, dairy products, and olive oil; and a low intake of meat. (6) Researchers have related high adherence to a Mediterranean diet to a lower risk of physical function impairments in older people. (7) Olive oil consumption is a good source of monounsaturated fatty acids and it is also associated with the prevention of frailty. (8) Epidemiological research has shown that dairy products, fruits and vegetables, and micronutrients such as vitamins, calcium, folate and selenium can have protective effects against disability. (9-11) A higher consumption of fruits and vegetables is also linked to protective effects toward frailty (12), functional disability (13, 14) and sarcopenia. (15) Similarly, as the Mediterranean diet advocates the consumption of good quality protein, such as fish and lean meat, this type of diet has been shown to be protective of frailty (16), and sarcopenia parameters in the elderly. (17-20)

It is known that the aging process may lead to a decline in physical function. (21) Conditions such as frailty, functional disability and sarcopenia negatively impact older persons’ quality of life and increase morbidity and mortality rates (22-24), resulting in a potential influence on public healthcare expenditures. (25) Therefore, these conditions have been considered for investigation in this study.

For some time, functional disability was referred to as a synonym for frailty given their co-occurrence and similarities. However, it is now known that although both conditions are related to each other and may co-occur in a person, they are not the same. (22) While frailty is characterized by a state of vulnerability to adverse health outcomes given to a deregulation in multiple physiologic systems (22, 26), functional disability is the presence of difficulty or dependency in carrying out essential activities of independent living. (22) Differentiating between frailty and functional disability may help to understand these conditions and might offer new strategies for their prevention and the care of older persons. (12, 27) Sarcopenia is often reflected as an important element of frailty and functional disability. (25, 26) It is characterized by the loss of muscle mass or strength related to age (24, 28), leading to decreased independence, increased number of falls and fractures. (29, 30)

Despite the large body of evidence concerning the improvement of general health and the prevention of chronic non-communicable diseases among young adults who adhere to the Mediterranean diet, few studies have extended these benefits to older adults. As frailty, functional disability and sarcopenia can lead to serious negative consequences for older people, and the Mediterranean diet might influence the prevention of these conditions, this study reviewed the literature on this topic. The present study investigated the association between the adherence to a Mediterranean diet pattern and sarcopenia, frailty and functional disability in older adults through a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods and Settings

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist. (31)

Record and protocol

The systematic review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), under registration number CRD42016052473.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion Criteria: Observational studies (cohort, casecontrol and analytical cross-sectional that investigated the association between adherence to a Mediterranean diet and frailty, functional disability, or sarcopenia in communitydwelling individuals aged ≥60 years old. Eligible studies assessed a Mediterranean diet defined a priori, comparing the highest adherence score with the lowest one. There was no restriction regarding the language, period or publication status in order to reduce publication and retrieval bias.

Assessment of the Mediterranean diet

The Mediterranean diet defined a priori can be assessed using scales or scores. The most common way of assessing it is through the Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS). (32) Nowadays, there are modified versions of the MDS that can be used to assess adherence to this diet. Fung et al, for example, adapted the Greek version of the MDS to be applied in a non- Mediterranean country. (33) The MeDi score is another used way of assessing adherence to a Mediterranean diet, and it was developed using dietary consumption data. (34, 35)

Assessment of frailty, functional disability and sarcopenia

The outcomes addressed in this review are frailty, functional disability and sarcopenia. Frailty can be assessed using the frailty phenotype (27), which evaluates the presence of unintentional weight loss, weakness, poor endurance or exhaustion, slowness and low activity level. Morley et al, for example, developed modified diagnostic criteria for frailty where low activity was substituted by illness. (36) Functional disability is usually assessed using Activities of Daily Living scale (37) and, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale. (38) However, this outcome can also be identified using the Short Physical Performance Battery, the Rosow and Breslau disability scale, the SF-12 questionnaire and the Physical Function Questionnaire. (39, 40) Sarcopenia may be assessed by measuring muscle mass (using dual-energy x ray) or appendicular lean mass, muscle strength (grip strength) and physical performance (leg explosive power). (41, 42)

This systematic review included studies that used either the original tools and parameters, or their modified versions to define the exposure and outcomes investigated.

Exclusion Criteria: Studies with (1) HIV positive patients or elderly diagnosed with neurodegenerative diseases, (2) participants diagnosed with any of the three outcomes of interest at the beginning of the follow-up period, (3) institutionalized elderly patients, (4) elderly presenting an inadequate caloric consumption (<500 kcal or>4,000 kcal), (5) the evaluation of dietary patterns derived a posteriori or consumption of specific types of food and beverages, ingestion or adequacy of nutrients or use of nutritional supplements, (6) reviews, letters and editorials.

Odds Ratios (OR) regarding the association between adherence to a Mediterranean diet and frailty, functional disability and sarcopenia with a 95% confidence interval were included in the meta-analysis. Sample size of the selected articles, studies methodological quality, and different assessments of adherence to a Mediterranean diet were not considered as exclusion criteria.

Sources of information and search strategy

The literature searches for eligible articles were performed on September 8, 2016 (first search) and November 28, 2016 (last search), using the following electronic databases: MEDLINE (via PubMed), EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus, CINAHL, LILACS and SciELO. A search on the grey literature was also performed using Google Scholar and ProQuest. The Google Scholar search was limited to the first 60 most relevant articles. Additional articles were identified by hand searching the reference sections of papers included in the review.

To perform the search strategy, we used MeSH terms for PubMed and EMTREE terms for EMBASE, as well as a combination of keywords. The Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist was applied, which is an instrument used for independent and peer review of the search strategy. This tool evaluates the correct use of Boolean operators (e.g., AND, OR), topics related to the research question, spelling of terms, and filters to expand or restrict the search. (43)

The following search strategy was applied primarily to PubMed and later adapted to other databases: (“older adults” OR elderly OR “older people”) AND (“Mediterranean diet” OR “dietary pattern” OR “dietary score” OR diet [Mesh] OR “dietary adherence” OR Mediterranean) AND (frail* OR frailty OR sarcopenia [Mesh] OR “physical disability” OR “functional disability” OR “disabled persons” [Mesh]).

Selection of studies

The study selection process was performed in two phases. In phase 1, two authors (RS and NP) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all electronic database citations. After the withdrawal of duplicate records, the titles and abstracts were evaluated, with discordant events to be resolved either by consensus or by a third author intervention (MKI). In phase 2, reading of the full texts was carried out independently by two authors (RS and NP), and articles that did not appear to meet the eligibility criteria were excluded.

Data extraction

Data from the selected articles were extracted to a Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet (2010) independently by three authors (RS, NP and FM). We selected the following information: author’s name, publication year, study country, data collection year, study group, study design, the Mediterranean diet adherence score, outcomes of interest (frailty, physical disability and sarcopenia), sample size, mean age, association measure and confidence interval. In the case of studies that used more than one score to assess adherence to a Mediterranean diet, we considered the Mediterranean Diet Score proposed by Trichopoulou et al. (32) By choosing this score, which is the most commonly used in the literature, we aimed to standardize the inter-study exposure measure. We contacted the authors in order to gather important additional information for the review and meta-analysis.

Methodological quality assessment

The Joanna Briggs Institute tools were used to evaluate the study quality. For cohort studies, the checklist evaluated eleven questions related to similarity between groups, exposure and outcome measures, strategies to control for confounding factors, absence or presence of the outcome at the beginning of followup, follow-up time and statistics. (44) For case-control studies, ten questions evaluated characteristics such as matching of cases and controls, comparability between groups, measurement of exposures and outcome and statistical analysis. (45) For analytical cross-sectional studies, the checklist was composed of eight questions related to inclusion and exclusion criteria, description of study participants, exposure definition and outcome measures, strategies to control for confounding factors, and statistical analysis. (46) Each question from the checklists could be answered with “yes” or “no”. The greater the number of “yes” answers, the higher the probability of being a good quality study. Two reviewers (RS and NP) independently assessed the quality of each study. Discordances were resolved by consensus or by a third author (FM).

Data analysis

Random-effects meta-analyses were performed using the DerSimonian and Laird method. The association measure used was odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The presence of heterogeneity between the studies was identified using the chi-square test (X2) at p <0.10. This more conservative p-value was adopted because the chi-square test has low power in meta-analyses that have few studies. (47) The magnitude of inconsistency was measured using the I-squared statistic (I2). Values of I2 higher than 75% indicate high heterogeneity, values between 75 and 50% are indicative of moderate heterogeneity, and lower than 25% of low heterogeneity. (47) All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 13®.

Results

Selection of studies

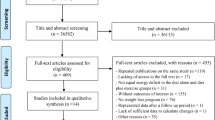

A total of 1,667 articles were retrieved from database searches. After removal of duplicates and the title/abstracts screening, 25 full-text articles were read and assessed for eligibility. In the end, 11 articles were considered for the systematic review. Eligible studies were published between 2011 and 2017. One article (7) presented information from two different studies; therefore, a total of 12 studies were included in the systematic review. Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the selection process.

Studies and participant characteristics

We included 8 cohort (n=12,230) (21, 34, 35, 48-52) and 4 analytical cross-sectional studies (n=8,288) (7, 53, 54) totaling 20,518 subjects. No case-control studies were found. The studies collected had average follow-up periods ranging from 3.5 (50) to 9 years (51). The majority of studies covered countries such as Italy (21, 51), Spain (50, 52) and China. (48, 49) The literature search provided 5 studies for frailty (21, 35, 48, 50, 53), 5 studies for disability (7, 34, 51, 52) and 2 studies for sarcopenia. (49, 54) In most studies, women represented the major proportion of the sample. (7, 21, 34, 35, 48, 49, 51, 53, 54) The mean age reported ranged from 68 (50, 52) to 84 years. (53) The main addressed confounders in the studies were age, sex, BMI, energy intake, educational level, chronic diseases or comorbidities, depression, alcohol use, smoking status and physical activity (Table 1).

Outcome definitions and quality assessment

Frailty was assessed using the frailty phenotype (21, 27, 53), modified versions of the frailty phenotype (35, 48), and the FRAIL Scale. (50) Disability assessment was based on five different methods and definitions: Activities of Daily Living (ADL) (7), ADL and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) scale (34), the Short Physical Performance Battery (51), the Physical Function Questionnaire (7) and the Rosow-Breslau scale and SF-12. (52) Sarcopenia was assessed using either the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia’s definition (49) or by evaluating sarcopenia parameters (skeletal muscle mass, strength and function/power). (54) Cohort and analytical crosssectional studies seemed to be of good quality, with an average of 7 and 10 “yes” answers, respectively. This result indicates that the studies included in this review have a low risk of bias, according to the items evaluated with the critical appraisal, such as identification of confounding factors and appropriate statistical analysis. (See Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Assessment of the Adherence to a Mediterranean diet

Adherence to a Mediterranean diet was assessed using the Trichopoulou index (32) in the majority of the studies (21, 48-52, 54), while the remaining studies used the modified version of the Trichopoulou index (7), the alternative Mediterranean Diet Score (53) and the MeDi Score. (34, 35)

Meta-analysis and the association between a Mediterranean diet and the outcomes

The meta-analysis was performed with 4 cohort studies (n=5,789) and showed that the highest adherence to the Mediterranean diet compared with the lowest one was associated with a reduced risk of frailty in community-dwelling older adults (OR 0.42, 95% CI: 0.28-0.65). We observed nonsignificant heterogeneity between these studies (I2=24.9%, p=0.262) (Figure 2). The cross-sectional study included in the review showed a positive association between higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet and lower odds of frailty in a sample of 192 community-dwelling older adults (OR 0.19, 95% CI: 0.05-0.82). (53)

The odds ratios from 3 cohort studies (n=3,493) were meta-analyzed and showed that there was a positive association between higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet and functional disability/disability parameters (OR 0.75, 95% CI: 0.61-0.93) in community-dwelling older adults. The I2statistic of 0.0% (p=0.78) suggests there was no significant between-study heterogeneity (Figure 3). Cross-sectional data from one study in this review (7) also showed a positive association between higher adherence to a Mediterranean diet and fewer disabilities in older people from Israel (OR 0.51, 95% CI: 0.27-0.93).

We could not perform a meta-analysis between adherence to a Mediterranean diet and sarcopenia due to different study designs between the selected studies. (49, 54) The cohort study included in the review failed to show association. (49) However, cross-sectional data from another study included in the review showed a positive association between adherence to a Mediterranean diet and sarcopenia parameters. (54)

Discussion

In this study, we systematically reviewed observational studies that investigated the association between Mediterranean diet adherence and three musculoskeletal-functional outcomes in community-dwelling older people. The main results showed that older people with higher adherence to a Mediterranean diet were less likely to develop frailty and functional disability. The results regarding sarcopenia were inconclusive.

The results showed that, in most studies included in this systematic review, women represented the major proportion of the sample. This information is similar to the latest United Nations worldwide demographics statistics; in 2015, women aged 60 and older represented 54% of the world’s population, and of those aged 80 and over, women represented 61%. (5)

A Mediterranean diet has been suggested as a key element for the prevention of age-related chronic diseases, and it is related to a decreased risk all-cause mortality (55) of cardiovascular diseases (56), different types of cancer (57), musculoskeletal-functional (58), and cognitive diseases. (59) The outcomes reported in this systematic review are related, composing a progressive process. Sarcopenia precedes frailty and functional disability, as frailty is a risk factor for functional disability. (25-27) Both cohort and cross-sectional data from our study showed that older people with higher adherence to a Mediterranean diet have a reduced probability of developing frailty and functional disability and sarcopenia (cross-sectionally). The dietary components of a Mediterranean diet, such as fruits and vegetables, serve as main nutritional sources of antioxidants needed for correct action of metabolism enzymes. A dose-response analysis from 3 European cohorts showed that community-dwelling older people with a higher consumption of fruits and vegetables had a lower risk of frailty. (12) Regarding anti-inflammatory effects, Mediterranean diet stimulates fish intake, a source of polyunsaturated fatty acids; a higher intake of these nutrients is related to less muscular tissue oxidative stress and a lower inflammatory response (60) and a lower inflammatory body status. (20, 61) Another mechanism of action that contributes to elucidate the beneficial actions of the Mediterranean diet is the phytochemicals presented in other items, such as red wine, fruits and vegetables that also have strong anti-inflammatory properties, and are related to protect against the accentuated inflammation in frail older people. (62)

Absence of functional disability or activity limitation is a major component of successful aging, and the disablement process leads to a poorer quality of life. (34) The biological basis for the apparent benefits of the Mediterranean diet in preventing disability and frailty is the reduced oxidative stress and inflammation status. In the InCHIANTI (Invecchiare in Chianti, aging in the Chianti region) study, high-plasma carotenoids protected against declines in walking speed and in the development of a severe walking disability in adults aged 65–102 years, as well as influenced a reduced inflammation status. (63) A cohort study performed with Japanese older adults showed that a dietary pattern rich in fruits, vegetables and fish was inversely associated with a lower risk of disability. (64) The cross-sectional study included in our review showed that higher adherence to a Mediterranean diet was inversely associated with sarcopenia parameters in older women. These results were also seen in another cross-sectional analysis of older women from the OSPRE-FPS cohort. (65) Longitudinal data failed to show an association between adherence to a Mediterranean diet and the risk of sarcopenia in a Chinese cohort study included in this review. This result may be explained due to the lower consumption of olive oil, nuts and wine in this population compared with those who live in the Mediterranean region. (49)

Regarding the three outcomes reported in this study, the most addressed confounding variables in the adjusted analyses of the original articles were age, sex, BMI, energy intake, educational level, chronic diseases or comorbidities, depression, alcohol use, smoking status and physical activity. Physical activity and other lifestyle factors such as leisure time outdoors and having meals with family can be confounders in the relationship between the Mediterranean diet and frailty, functional disability and sarcopenia. (66, 67)

It is known that this dietary pattern is present in many countries across the Mediterranean region, but it is also identified in non-Mediterranean countries, such as the United States of America, Iran, China, Japan and Germany. Differences in the production and preparation of food may affect the potential benefits from this diet. Submitting olive oil to high temperatures, eating vegetables but not much from the dark green leaf ones, eating fruits that are not raw, consuming salty nuts, refined salted or sweetened cereals, and consuming baked and canned beans are a few examples of the differences on how food is prepared and consumed between Mediterranean and non-Mediterranean countries. These factors combined with the lifestyle factors mentioned above is may affect the overall benefit of the Mediterranean diet. (66, 67)

The results obtained in this systematic review should be interpreted within its limitations. First, the meta-analyses performed for frailty and functional disability generated pooled ORs from adjusted measures provided by the authors. It was not possible to access crude ORs and then calculate the pooled measure because the studies included in the review did not include enough data for this purpose; moreover, this information could not be obtained by contacting the authors. The pooled ORs were not generated from incidence measures; the majority of studies included only baseline association measures between adherence to a Mediterranean diet and the outcomes. Second, since this review included fewer than 10 studies for each outcome, we could not perform metaregressions or other sensitivity analyses to investigate possible sources of heterogeneity. The pooled OR for frailty presented 41% heterogeneity, and variables such as definitions of outcomes, sample size and location of the study may have influenced this variability between the studies. Third, our meta-analyses were performed using measures that did not consider the period of time each participant was in the study. Therefore, we encourage future studies to analyze this relationship considering person-time measures. Fourth, we could not perform a meta-analysis for sarcopenia, as the studies included for this outcome had different methodological designs. Although we could not obtain a pooled OR for sarcopenia, it is important to state that the lack of association between adherence to a Mediterranean diet and sarcopenia observed in this review may be a false negative since we included only two studies. More studies are needed to detect this association.

In our view, this was the first systematic review to investigate the association between the adherence to a Mediterranean diet and frailty, functional disability and sarcopenia. It is known that sarcopenia is related to both frailty and disability; the available studies show that a Mediterranean diet is inversely associated with sarcopenia. Since sarcopenia precedes the process of frailty and functional disability (27), more studies are needed to provide results regarding the prevention of sarcopenia. We also conducted a broad literature search of 10 databases and the grey literature. Additionally, corresponding authors were contacted for additional information relevant to this review.

In conclusion, higher adherence to a Mediterranean diet was protective of frailty and functional disability. Overall, the Mediterranean dietary pattern probably contributes to the understanding of good health parameters in people who have a high adherence to this diet. Further longitudinal studies in different populations are needed to confirm this association and to understand the potential protective effect of the Mediterranean diet on sarcopenia.

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standard: There is no ethical standard for this study design.

References

Sofi F, Macchi C, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Mediterranean diet and health status: an updated meta-analysis and a proposal for a literature-based adherence score. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(12):2769–82.

Dyer J, Davison G, Marcora SM, Mauger AR. Effect of a Mediterranean Type Diet on Inflammatory and Cartilage Degradation Biomarkers in Patients with Osteoarthritis. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21(5):562–6.

Palloni A, Pinto-Aguirre G, Pelaez M. Demographic and health conditions of ageing in Latin America and the Caribbean. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(4):762–71.

Bamford S-M, Serra V. Non-Communicable Diseases in an Ageing World. A report from the International Longevity Centre UK, Help Age International and Alzheimer’s Disease International lunch debate. United Kingdom 2011.

UN. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2015). World Population Ageing 2015 (ST/ESA/SER.A/390).

Trichopoulou A, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Anatomy of health effects of Mediterranean diet: Greek EPIC prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:b2337.

Zbeida M, Goldsmith R, Shimony T, Vardi H, Naggan L, Shahar DR. Mediterranean diet and functional indicators among older adults in non-Mediterranean and Mediterranean countries. J Nutr Health Aging. 2014;18(4):411–8.

Sandoval-Insausti H, Pérez-Tasigchana RF, López-García E, García-Esquinas E, Rodríguez-Artalejo F, Guallar-Castillón P. Macronutrients Intake and Incident Frailty in Older Adults: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71(10):1329–34.

Houston DK, Stevens J, Cai J, Haines PS. Dairy, fruit, and vegetable intakes and functional limitations and disability in a biracial cohort: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81(2):515–22.

Bartali B, Semba RD, Frongillo EA, Varadhan R, Ricks MO, Blaum CS, et al. Low micronutrient levels as a predictor of incident disability in older women. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2335–40.

Vercambre MN, Boutron-Ruault MC, Ritchie K, Clavel-Chapelon F, Berr C. Longterm association of food and nutrient intakes with cognitive and functional decline: a 13-year follow-up study of elderly French women. Br J Nutr. 2009;102(3):419–27.

García-Esquinas E, Rahi B, Peres K, Colpo M, Dartigues JF, Bandinelli S, et al. Consumption of fruit and vegetables and risk of frailty: a dose-response analysis of 3 prospective cohorts of community-dwelling older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104(1):132–42.

Xu B, Houston D, Locher JL, Zizza C. The association between Healthy Eating Index-2005 scores and disability among older Americans. Age Ageing. 2012;41(3):365–71.

Semba RD, Varadhan R, Bartali B, Ferrucci L, Ricks MO, Blaum C, et al. Low serum carotenoids and development of severe walking disability among older women living in the community: the women’s health and aging study I. Age Ageing. 2007;36(1):62–7.

Neville CE, Young IS, Gilchrist SE, McKinley MC, Gibson A, Edgar JD, et al. Effect of increased fruit and vegetable consumption on physical function and muscle strength in older adults. Age (Dordr). 2013;35(6):2409–22.

Kobayashi S, Suga H, Sasaki S, Group T-gSoWoDaHS. Diet with a combination of high protein and high total antioxidant capacity is strongly associated with low prevalence of frailty among old Japanese women: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Nutr J. 2017;16(1):29.

Bosaeus I, Rothenberg E. Nutrition and physical activity for the prevention and treatment of age-related sarcopenia. Proc Nutr Soc. 2016;75(2):174–80.

Isanejad M, Mursu J, Sirola J, Kröger H, Rikkonen T, Tuppurainen M, et al. Dietary protein intake is associated with better physical function and muscle strength among elderly women. Br J Nutr. 2016;115(7):1281–91.

Rondanelli M, Faliva M, Monteferrario F, Peroni G, Repaci E, Allieri F, et al. Novel Insights on Nutrient Management of Sarcopenia in Elderly. BioMed Research International. 2015;2015:1–14.

Gray SR, Da Boit M. Fish Oils and their Potential in the Treatment of Sarcopenia. J Frailty Aging. 2013;2(4):211–6.

Talegawkar SA, Bandinelli S, Bandeen-Roche K, Chen P, Milaneschi Y, Tanaka T, et al. A higher adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet is inversely associated with the development of frailty in community-dwelling elderly men and women. J Nutr. 2012;142(12):2161–6.

Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(3):255–63.

Keeler E, Guralnik JM, Tian H, Wallace RB, Reuben DB. The impact of functional status on life expectancy in older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(7):727–33.

Visser M, Schaap LA. Consequences of sarcopenia. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27(3):387–99.

Clark BC, Manini TM. Functional consequences of sarcopenia and dynapenia in the elderly. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13(3):271–6.

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–62.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–56.

Marcell TJ. Sarcopenia: causes, consequences, and preventions. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(10):M911–6.

Lang T, Streeper T, Cawthon P, Baldwin K, Taaffe DR, Harris TB. Sarcopenia: etiology, clinical consequences, intervention, and assessment. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(4):543–59.

Landi F, Liperoti R, Russo A, Giovannini S, Tosato M, Capoluongo E, et al. Sarcopenia as a risk factor for falls in elderly individuals: results from the ilSIRENTE study. Clin Nutr. 2012;31(5):652–8.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):1–6.

Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2599–608.

Fung TT, McCullough ML, Newby PK, Manson JE, Meigs JB, Rifai N, et al. Dietquality scores and plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(1):163–73.

Féart C, Pérès K, Samieri C, Letenneur L, Dartigues JF, Barberger-Gateau P. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and onset of disability in older persons. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26(9):747–56.

Rahi B, Ajana S, Tabue-Teguo M, Dartigues JF, Peres K, Feart C. High adherence to a Mediterranean diet and lower risk of frailty among French older adults communitydwellers: Results from the Three-City-Bordeaux Study. Clin Nutr. 2017.

Morley JE, Malmstrom TK, Miller DK. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(7):601–8.

Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, Grotz RC. Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist. 1970;10(1):20–30.

Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–86.

MAHONEY FI, BARTHEL DW. FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION: THE BARTHEL INDEX. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–5.

Granger C, Hamilton B, Keith R, Zielezny M, Sherwin F. Advances in functional assessment for medical rehabilitation. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 1986;1(3):59–74.

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Cederholm T, Landi F, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010;39(4):412–23.

Cederholm TE, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Schneider SM, Sieber CC, Rolland Y. Toward a definition of sarcopenia. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27(3):341–53.

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6.

JBI. JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cohort Studies. Australia: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2016.

Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017.

JBI. JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies. Australia: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2016.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in metaanalyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Chan R, Leung J, Woo J. Dietary Patterns and Risk of Frailty in Chinese Community-Dwelling Older People in Hong Kong: A Prospective Cohort Study. Nutrients. 2015;7(8):7070–84.

Chan R, Leung J, Woo J. A Prospective Cohort Study to Examine the Association Between Dietary Patterns and Sarcopenia in Chinese Community-Dwelling Older People in Hong Kong. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(4):336–42.

León-Muñoz LM, Guallar-Castillón P, López-García E, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. Mediterranean diet and risk of frailty in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(12):899–903.

Milaneschi Y, Bandinelli S, Corsi AM, Lauretani F, Paolisso G, Dominguez LJ, et al. Mediterranean diet and mobility decline in older persons. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46(4):303–8.

Struijk EA, Guallar-Castillón P, Rodríguez-Artalejo F, López-García E. Mediterranean dietary patterns and impaired physical function in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;00(00):1–7.

Bollwein J, Diekmann R, Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Uter W, Sieber CC, et al. Dietary quality is related to frailty in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(4):483–9.

Kelaiditi E, Jennings A, Steves CJ, Skinner J, Cassidy A, MacGregor AJ, et al. Measurements of skeletal muscle mass and power are positively related to a Mediterranean dietary pattern in women. Osteoporos Int. 2016.

Limongi F, Noale M, Gesmundo A, Crepaldi G, Maggi S. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and All-Cause Mortality Risk in an Elderly Italian Population: Data from the ILSA Study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21(5):505–13.

Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, Covas MI, Corella D, Arós F, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1279–90.

Whalen KA, McCullough ML, Flanders WD, Hartman TJ, Judd S, Bostick RM. Paleolithic and Mediterranean Diet Pattern Scores Are Inversely Associated with Biomarkers of Inflammation and Oxidative Balance in Adults. J Nutr. 2016;146(6):1217–26.

Yannakoulia M, Ntanasi E, Anastasiou CA, Scarmeas N. Frailty and nutrition: From epidemiological and clinical evidence to potential mechanisms. Metabolism. 2017;68:64–76.

Wu L, Sun D. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of developing cognitive disorders: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41317.

de Gonzalo-Calvo D, de Luxán-Delgado B, Rodríguez-González S, García-Macia M, Suárez FM, Solano JJ, et al. Oxidative protein damage is associated with severe functional dependence among the elderly population: a principal component analysis approach. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(6):663–70.

Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Nicklas B, Kanaya AM, Patrignani P, Tacconelli S, et al. Oxidative damage, platelet activation, and inflammation to predict mobility disability and mortality in older persons: results from the health aging and body composition study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(6):671–6.

Li H, Manwani B, Leng SX. Frailty, inflammation, and immunity. Aging Dis. 2011;2(6):466–73.

Cesari M, Pahor M, Bartali B, Cherubini A, Penninx BW, Williams GR, et al. Antioxidants and physical performance in elderly persons: the Invecchiare in Chianti (InCHIANTI) study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(2):289–94.

Tomata Y, Watanabe T, Sugawara Y, Chou WT, Kakizaki M, Tsuji I. Dietary patterns and incident functional disability in elderly Japanese: the Ohsaki Cohort 2006 study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(7):843–51.

Isanejad M, Sirola J, Mursu J, Rikkonen T, Kröger H, Tuppurainen M, et al. Association of the Baltic Sea and Mediterranean diets with indices of sarcopenia in elderly women, OSPTRE-FPS study. Eur J Nutr. 2017.

Hoffman R, Gerber M. Evaluating and adapting the Mediterranean diet for non-Mediterranean populations: a critical appraisal. Nutr Rev. 2013;71(9):573–84.

Bertuccioli A, Ninfali P. The Mediterranean Diet in the era of globalization: The need to support knowledge of healthy dietary factors in the new socio-economical framework. Mediterranean Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism. 2014;7(1):75–86.

Bertoli S, Battezzati A, Merati G, Margonato V, Maggioni M, Testolin G, et al. Nutritional status and dietary patterns in disabled people. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2006;16(2):100–12.

Kim DH, Sagar UN, Adams S, Whellan DJ. Lifestyle risk factors and utilization of preventive services in disabled elderly adults in the community. J Community Health. 2009;34(5):440–8.

Tomata Y, Kakizaki M, Nakaya N, Tsuboya T, Sone T, Kuriyama S, et al. Green tea consumption and the risk of incident functional disability in elderly Japanese: the Ohsaki Cohort 2006 Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(3):732–9.

García-Esquinas E, León-Muñoz LM, Graciani A, Guallar-Castillón P, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. Consumption of fruits and vegetables and risk of frailty. Circulation. 2015;131.

Kim J, Lee Y, Kye S, Chung YS, Kim KM. Association between healthy diet and exercise and greater muscle mass in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(5):886–92.

Kim J, Lee Y, Kye S, Chung YS, Kim KM. Association of vegetables and fruits consumption with sarcopenia in older adults: the Fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Age Ageing. 2015;44(1):96–102.

Nakamura M, Ojima T, Nakade M, Ohtsuka R, Yamamoto T, Suzuki K, et al. Poor Oral Health and Diet in Relation to Weight Loss, Stable Underweight, and Obesity in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study From the JAGES 2010 Project. J Epidemiol. 2016;26(6):322–9.

Freisling H, Elmadfa I. Food frequency index as a measure of diet quality in non-frail older adults. Ann Nutr Metab. 2008;52:Suppl 1:43–6.

Shikany JM, Barrett-Connor E, Ensrud KE, Cawthon PM, Lewis CE, Dam TT, et al. Macronutrients, diet quality, and frailty in older men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(6):695–701.

Ortolá R, García-Esquinas E, León-Muñoz LM, Guallar-Castillón P, Valencia-Martín JL, Galán I, et al. Patterns of Alcohol Consumption and Risk of Frailty in Community-dwelling Older Adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71(2):251–8.

Yokoyama Y, Nishi M, Murayama H, Amano H, Taniguchi Y, Nofuji Y, et al. Association of Dietary Variety with Body Composition and Physical Function in Community-dwelling Elderly Japanese. J Nutr Health Aging. 2016;20(7):691–6.

Hashemi R, Motlagh AD, Heshmat R, Esmaillzadeh A, Payab M, Yousefinia M, et al. Diet and its relationship to sarcopenia in community dwelling Iranian elderly: a cross sectional study. Nutrition. 2015;31(1):97–104.

Vuolo L, Barrea L, Savanelli MC, Savastano S, Rubino M, Scarano E, et al. Nutrition and Osteoporosis: Preliminary data of Campania Region of European PERsonalised ICT Supported Service for Independent Living and Active Ageing. Transl Med UniSa. 2015;13:13–8.

Kelaiditi E. Diet, inflammation and skeletal muscle mass in women. United Kingdom: University of East Anglia; 2013.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Silva, R., Pizato, N., da Mata, F. et al. Mediterranean Diet and Musculoskeletal-Functional Outcomes in Community-Dwelling Older People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Nutr Health Aging 22, 655–663 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-017-0993-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-017-0993-1